Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 106

February 21, 2012

The Electoral College–Not a Party School

The Electoral College is NOT a Party School

Grown men turn weak and stammer when asked who makes up the Electoral College. The subject of a once-every-four-years debate over its existence, the institution plods on, an enigma to those Americans who think the voters decide who will be president.

Like many creations of the American political system, the Electoral College was the result of a compromise. When the Framers sat down to write the Constitution in the summer of 1787 and figure out the rules for electing the president, there was only one certainty: George Washington would be the first president. As Ben Franklin told the delegates, "The first man at the helm will be a good one. Nobody knows what sort may come afterwards."

One solution was allowing the legislature –Congress- to choose. Men who wanted to maintain separation of powers between the branches saw this as dangerous. Congress might too easily influence a president chosen by legislators.

To most of us today, the obvious answer would have been direct election by the people. But this was opposed by many of the Framers. They had legitimate practical concerns: how could a voter in Massachusetts know a candidate from Virginia or South Carolina in late eighteenth-century America? They also feared corruption and bribery. And delegates from small states feared being overwhelmed by more populous states.

But the Framers also feared that too much democracy was a dangerous thing. To some of them, democracy was one step away from "mob rule." They also didn't believe that most people had the education (or intelligence) to make a wise choice.

To maintain control over the presidential process, they came up with the idea giving each state presidential "electors" equal to the number of its senators and representatives in Congress. These "electors," chosen by whatever means the separate states decided, would vote for two men. The candidate with a majority of electoral votes became president and the second-place finisher became vice president.

The fact that slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person meant slave states received electors out of proportion to their free, white population –providing a large measure of the "slave power" that meant that five of the first seven presidents were slaveholding, two-term presidents.

But the safety valve built into this plan was the agreement that if the electoral vote failed to produce a winner, the election would be sent to the House of Representatives, where each state would get a single vote. In an era in which political parties were disdained, the common wisdom was that after George Washington, no man could win the votes needed for election, and the real decisions would be made by the enlightened gentlemen in Congress.

Within a short time after Washington, two presidential elections failed to produce a victor and were sent to the House of Representatives. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, from the same party, received seventy-three electoral votes each. The election went to the House, which put Jefferson in the White House. Following this election, the voting for president and vice president was separated under the Twelfth Amendment.

Then, in 1824, Andrew Jackson led in the popular vote but failed to win a majority of electoral votes. In this case, the House of Representatives bypassed Jackson in favor of John Quincy Adams.

The popular vote winner has lost the election three more times. In 1876, Samuel J. Tilden beat Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote. But a controversial post-election commission gave Hayes enough tainted electoral votes to seal the victory. Then again in 1888, Grover Cleveland won the popular vote but lost to Benjamin Harrison in the Electoral College. Finally in 2000, Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the electoral vote after the long recount battle in Florida and the Supreme Court decision that favored Bush.

Today, the Electoral College is 538 Electors, equal to the 435 members of the House and 100 members of the Senate, plus three electoral votes for the District of Columbia. (Residents of Washington, D.C. did not vote for President until ratification of the 23rd Amendment in 1961.)

And who are the mysterious electors? These people, who cannot be members of Congress, are mostly party loyalists and state elected officials selected by their state political parties to fulfill the largely ceremonial task of casting the electoral votes that were decided on Election Day. States have their own rules as to how Electors must vote.

The "Electoral College" is administered by the National Archives and Records Administration which maintains a website providing more detail about electors and state-by-state rules that govern them.

You can read more about Election history and the Constitutional Compromises in Don't Know Much About History and America's Hidden History.

Don't Know Much About@ History (2011 Revised and Updated Edition)

A Nation Rising: A Video Q&A with Author Kenneth C. Davis

(Originally recorded in May 2010)

"With his special gift for revealing the significance of neglected historical characters, Kenneth Davis creates a multilayered, haunting narrative. Peeling back the veneer of self-serving nineteenth-century patriotism, Davis evokes the raw and violent spirit not just of an 'expanding nation,' but of an emerging and aggressive empire."

-Ray Raphael, author of Founders

February 20, 2012

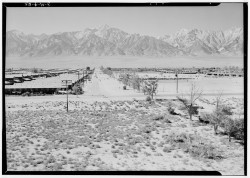

Don't Know Much About® Ansel Adams

Born today –February 20 in 1902– a man who changed how we see the world, Ansel Adams.

It was the photography that launched a thousand calendars, posters, and greeting cards. You have seen his ethereal outdoor photography –maybe even if you did not know it.

But you may not know about another side of his work: In 1943, Adams photographed Manzanar, the Japanese internment camp. The Library of Congress offers an online exhibit of Adams' wartime photos of Japanese Americans.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Ansel Adams, photographer, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-DIG-ppprs-00257

Of the photographs, Adams wrote, "The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment…

In an earlier post, I also wrote about photographer Dorothea Lange's work documenting the internment of Japanese Americans

Adams died at age 82 on April 22, 1984. Here is his New York Times obituary.

February 17, 2012

Electoral College–Not a Party School

The Electoral College is NOT a Party School

Grown men turn weak and stammer when asked who makes up the Electoral College. The subject of a once-every-four-years debate over its existence, the institution plods on, an enigma to those Americans who think the voters decide who will be president.

Like many creations of the American political system, the Electoral College was the result of a compromise. When the Framers sat down to write the Constitution in the summer of 1787 and figure out the rules for electing the president, there was only one certainty: George Washington would be the first president. As Ben Franklin told the delegates, "The first man at the helm will be a good one. Nobody knows what sort may come afterwards."

One solution was allowing the legislature –Congress- to choose. Men who wanted to maintain separation of powers between the branches saw this as dangerous. Congress might too easily influence a president chosen by legislators.

To most of us today, the obvious answer would have been direct election by the people. But this was opposed by many of the Framers. They had legitimate practical concerns: how could a voter in Massachusetts know a candidate from Virginia or South Carolina in late eighteenth-century America? They also feared corruption and bribery. And delegates from small states feared being overwhelmed by more populous states.

But the Framers also feared that too much democracy was a dangerous thing. To some of them, democracy was one step away from "mob rule." They also didn't believe that most people had the education (or intelligence) to make a wise choice.

To maintain control over the presidential process, they came up with the idea giving each state presidential "electors" equal to the number of its senators and representatives in Congress. These "electors," chosen by whatever means the separate states decided, would vote for two men. The candidate with a majority of electoral votes became president and the second-place finisher became vice president.

The fact that slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person meant slave states received electors out of proportion to their free, white population –providing a large measure of the "slave power" that meant that five of the first seven presidents were slaveholding, two-term presidents.

But the safety valve built into this plan was the agreement that if the electoral vote failed to produce a winner, the election would be sent to the House of Representatives, where each state would get a single vote. In an era in which political parties were disdained, the common wisdom was that after George Washington, no man could win the votes needed for election, and the real decisions would be made by the enlightened gentlemen in Congress.

Within a short time after Washington, two presidential elections failed to produce a victor and were sent to the House of Representatives. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, from the same party, received seventy-three electoral votes each. The election went to the House, which put Jefferson in the White House. Following this election, the voting for president and vice president was separated under the Twelfth Amendment.

Then, in 1824, Andrew Jackson led in the popular vote but failed to win a majority of electoral votes. In this case, the House of Representatives bypassed Jackson in favor of John Quincy Adams.

The popular vote winner has lost the election three more times. In 1876, Samuel J. Tilden beat Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote. But a controversial post-election commission gave Hayes enough tainted electoral votes to seal the victory. Then again in 1888, Grover Cleveland won the popular vote but lost to Benjamin Harrison in the Electoral College. Finally in 2000, Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the electoral vote after the long recount battle in Florida and the Supreme Court decision that favored Bush.

Today, the Electoral College is 538 Electors, equal to the 435 members of the House and 100 members of the Senate, plus three electoral votes for the District of Columbia. (Residents of Washington, D.C. did not vote for President until ratification of the 23rd Amendment in 1961.)

And who are the mysterious electors? These people, who cannot be members of Congress, are mostly party loyalists and state elected officials selected by their state political parties to fulfill the largely ceremonial task of casting the electoral votes that were decided on Election Day. States have their own rules as to how Electors must vote.

The "Electoral College" is administered by the National Archives and Records Administration which maintains a website providing more detail about electors and state-by-state rules that govern them.

You can read more about Election history and the Constitutional Compromises in Don't Know Much About History and America's Hidden History.

Don't Know Much About@ History (2011 Revised and Updated Edition)

February 16, 2012

Don't Know Much About® George Washington

When I was a kid, we got two holidays: one for Lincoln's Birthday and another for Washington's Birthday. Now, we have to make do with a three day weekend in February for what most people call "Presidents Day." But officially, it is still "Washington's Birthday." (Check out my other blog on Washington's Birthday for the explanation.)

Think you know about the Father of Our Country?

This video contains a few things that might surprise you.

Want to learn a little more?

Here is the website for the National Park Service's Birthplace of Washington site:

http://www.nps.gov/gewa/index.htm

And here is the National Park Service website for Fort Necessity, scene of Washington's surrender and "confession."

http://www.nps.gov/fone/index.htm

It is NOT Presidents Day. Or President's Day. Or Even Presidents' Day.

So What Day Is it After All?

Okay. We all do it. It's printed on calendars and posted in bank windows. We mistakenly call the third Monday in February Presidents Day, in part because of all those commercials in which George Washington swings his legendary ax and "Rail-splitter" Abe Lincoln hoists his ax to chop down prices on everything from linens to SUVs.

But, really it is George Washington's Birthday –federally speaking that is.

The official designation of the federal holiday observed on the third Monday of February was, and still is, Washington's Birthday.

You can also check out my videoblog on George Washington.

But Washington's Birthday has become widely known as Presidents Day (or President's Day, or even Presidents' Day). The popular usage and confusion resulted from the merging of what had been two widely celebrated Presidential birthdays in February –Lincoln's on February 12th, which was never a federal holiday– and Washington's on February 22.

Created under the Uniform Holiday Act of 1968, which gave us three-day weekend Monday holidays, the federal holiday on the third Monday in February is technically still Washington's Birthday. But here's the rub: the holiday can never land on Washington's true birthday because the latest date it can fall is February 21, as it did in 2011.

Washington's Tomb -- Mt. Vernon (Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis 2010)

Just because it is officially Washington's Birthday doesn't mean we can't talk about the other Presidents too. So here's a quick Presidential Pop Quiz:

•Who was the first President born an American citizen?

Martin van Buren, the eighth, also known as "Old Kinderhook," or "OK". All of his predecessors were born British subjects during the colonial era.

•Who was the first President to commit troops to a foreign country?

From 1801 to 1805, Thomas Jefferson sent the navy and marines to "Barbary" in what is modern day Libya, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia to attack the pirates who were preying on American and European shipping.

•Washington was the first general to become President. But how many other generals became President?

Eleven. Besides Washington, five were career officers: Andrew Jackson (Creek War, War of 1812); William Henry Harrison (Battle of Tippecanoe); Zachary Taylor (Mexican War); Grant (Civil War); and Eisenhower (WW II). Six others were not career soldiers but attained the rank by appointment: Franklin Pierce, (Mexican War); Andrew Johnson, Rutherford B. Hayes, James Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, and Benjamin Harrison (all of whom served in the Civil War).

Ironically, the two greatest war Presidents, Lincoln and Roosevelt, had little or no military experience. Lincoln was briefly in the Illinois militia, or national guard, during the Black Hawk War and later said he led a charge against an onion field and lost a lot of blood to mosquitoes.

During World War I, Roosevelt was Undersecretary of the Navy and had tried to enlist, but was asked to remain in his navy office. And many other Presidents had military experience but never attained the rank of general.

•Which President dodged the draft, legally?

During the Civil War, Grover Cleveland paid for a substitute when he was drafted. That was legal at the time under the 1863 Conscription Act.

•Which two Presidents died on the Fourth of July, 50 years after the Declaration of Independence was signed?

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams in 1826. James Monroe also died on July 4, 1831, and Calvin Coolidge was born in Vermont on Independence Day.

•Did President Lincoln write the Gettysburg Address on the back of an envelope?

That's the myth. But no, Lincoln drafted what may be the most memorable speech in American history several times. At Gettysburg for the dedication of a cemetery to the thousands who had died in the 1863 battle, Lincoln was not the featured speaker. That honor went to a man who spoke for two hours. Lincoln's address took about two and half minutes. But which one do we remember?

•Which President returned to the House of Representatives after his term?

John Quincy Adams

Many of these questions are drawn from Don't Know Much About History or my children's book Don't Know Much About the Presidents

February 10, 2012

Don't Know Much About Minute: Abraham Lincoln's Birthday

February 12 used to mean something–Lincoln's Birthday. It was never a national holiday but it was pretty important when I was a kid.

The Uniform Holidays Act in 1971 changed that by creating Washington's Birthday as a federal holiday on the third Monday in February. It is NOT officially Presidents Day.

But it is still a good excuse to talk about Abraham Lincoln. especially since his real birthday is on the calendar.

Honest Abe. The Railsplitter. The Great Emancipator. You know some of the basics and the legends. But check out this video to learn some of things you may not know, but should, about the 16th President.

Here's a link to the Lincoln Birthplace National Park

This link is to the Emancipation Proclamation page at the National Archives.

And you can read much more about Lincoln in Don't Know Much About History and Don't Know Much About the Civil War.

Don't Know Much About@ History (2011 Revised and Updated Edition)

The paperback edition had been released witha new cover to mark the 150th anniversary of the Civil war.

February 2, 2012

Joyce, Jesus, Goddesses & Groundhogs

Today is an auspicious date on the literary and liturgical calendars. James Joyce was born near Dublin on February 2, 1882 and his masterpiece Ulysses was published this date in 1922. (For more on Joyce and his birthday and works, see the Joyce Center in Dublin.)

This got me to thinking about things Irish and the fact that this date (sometimes February 1st) is also the day on which the ancient Celts celebrated imbolc, a sacred day heralding the approach of spring, and a day which honors the Irish goddess Bridget, patron of fire and poetry. How Joycean!

And it is also St. Bridget's Day –Bridget being the second most prominent Irish saint after Patrick. But she may also be related to that much older figure in Irish mythology, the goddess Bridget.

On top of that it Candlemas and Groundhog Day.

So how do we tie all these pieces together?

To me — and possibly to James Joyce, lover of things mythic, Christian and Irish—it is a wonderful case of ancient myths colliding with Christianity.

First, to explain Candlemas. It is a Christian holiday that celebrates the day on which Jesus was taken to the temple to be presented as an infant. Adding 40 days to Christmas Day arrives at the date. It would have been the earliest date at which Mary could have entered the temple after giving birth to be ritually purified. The words "candle mass" refers to the tradition of blessing of holy candles that would be used throughout the year. (Candlemas is also known variously as The Feast of the Presentation or the Feast of the Purification of Mary).

But in medieval Germany, it was on Candlemas Day that the groundhog was supposed to pop out of his hole to check for the weather. If the day was clear and he saw his shadow, he returned to hibernation. But if it was cloudy, the weather would moderate and spring would come early. German settlers brought that tradition to America and especially to Pennsylvania. (You know all about Punxsutawney Phil by now.) There are similar ancient traditions in Scotland and parts of England.

Back to Ireland where the pre-Christian Celtic imbolc celebrated the coming of spring as ewes began to lactate before giving birth to the spring lambs. But the Irish also believed that a serpent emerged on imbolc to determine if the winter would end. And on imbolc, the goddess Bridget walked the earth as a harbinger of the return of fertility, And it was day of a great bonfire that would purify the earth. As Ireland was Christianized, the goddess Bridget morphed into the legendary figure of Bridget, who was later sainted, and famed for keeping a sacred fire burning.

Put all these things together and you have a rich tapestry of pagan and Christian traditions that merge on February 2. Special animals forecast the coming of spring. The earth is purified by bonfires. Mary is purified and so are the holy candles. Spring and life are returning to earth and the lambs are about to be born, and the Lamb of God has been presented at the temple.

Whether you believe any of these traditions or none, it is fascinating to see all these threads come together on a day most Americans simply associate with men in top hats and fancy clothes watching for a large, furry rodent to emerge from a hole in the ground.

You can read more about Bridget, the goddess and the saint, in Don't Know Much About Mythology.

January 13, 2012

"Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution" –MLK and OWS

On Monday, the nation will celebrate Martin Luther King Day, honoring the birth of the slain civil rights leader on January 15, 1929. The obligatory snippets of the "I Have a Dream" speech will air on television. But Dr. King's life was about more than one speech — or one issue.

In a previous post I wrote about Coxey's Army, an 1894 protest march, and its connection to the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) Movement. That got me to thinking about where Occupy Wall Street would fit into Dr. King's worldview. One of the last sermons he delivered offers more than a clue.

On March 31, 1968, a few days before his death on April 4, 1968, Dr. King spoke at the National Cathedral in Washington about the plans for the Poor People's Campaign, an ambitious program to end poverty with jobs, improve housing and raise incomes for poor Americans of all races. Another march on Washington was scheduled to begin in May 1968.

In this speech, "Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution," King addressed the two evils he was working to overcome besides racial injustice: poverty, which knows no color in America, and war, then specifically the war in Vietnam. The text of the entire speech can be found online at Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University.

Most people associate Dr. King exclusively with the civil rights struggle. But he understood that social justice could not happen without economic justice. And that war was not the answer.

Would Dr. King be on the streets with OWS? I'll leave that to others to say for certain. But on Monday, read one of his last sermons and you may get the answer.

January 12, 2012

Don't Know Much About® Jack London

Born this date in 1876, American novelist, short story writer and political essayist Jack London.

You probably remember him for his tales of dogs in the Alaskan wilderness, including The Call of the Wild and White Fang. He wrote his most famous works after spending time in Alaska during the Gold Rush.

But London was much more than a writer of wilderness adventures. As a young man, he was briefly caught up in Kelly's Army, part of a larger protest movement called "Coxey's Army." It was the "Occupy Wall Street" of the 1890s.

Following an economic depression in 1893 –the largest economic downturn in American history to that time– a group of unemployed American began a march on Washington. They were led by Jacob Coxey and were eventually called "Coxey's Army." In 1894, they began a protest march, hoping to force the federal government to do more to help out-of-work Americans with road building and other public works projects. It was one part of the growing populist and labor movements of the day and was met with predictable disdain by politicians. This is a report from the New York Times from March 1894.

Out West, the movement spawned "Kelly's Army" and a young Jack London joined up. He later wrote about the experience in a piece called "Two Thousand Stiffs."

In the evenings our camps were invaded by whole populations. Every company had its campfire, and around each fire something was doing. The cooks in my company, Company L, were song-and-dance artists and contributed most of our entertainment. In another part of the encampment the glee club would be singing . . . All these things ran neck and neck; it was a full-blown Midway. A lot of talent can be dug out of two thousand hoboes. I remember we had a picked baseball nine, and on Sundays we made a practice of putting it all over the local nines. Sometimes we did it twice on Sundays.

London later became a Socialist and was a passionate unionist and advocate of workers' rights. They probably didn't tell you that when they assigned White Fang in junior high.

There is a great collection of London material, including writings, biographical and critical material at Sonoma State University's Jean and Charles Schultz Information Center.

London died on November 22, 1916. This is his New York Times obituary.

His home is now a California State Park