Vicki Cobb's Blog, page 3

February 19, 2020

An Honorable President

Painting by Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860) I am not a historian. But one of my greatest joys has come from reading history as written by iNK history writers. Yet my knowledge has gaps, which I try to fill. For the past few days, the History Channel has run a miniseries on George Washington. Suddenly, he is no longer a clichéd

Painting by Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860) I am not a historian. But one of my greatest joys has come from reading history as written by iNK history writers. Yet my knowledge has gaps, which I try to fill. For the past few days, the History Channel has run a miniseries on George Washington. Suddenly, he is no longer a clichéd"father of our country" or the somewhat sour face on a dollar bill. Despite his flaws which included his strong temper and depending on enslaved people to run his farm, this series illuminated how his most important trait, his character, was built.

In the eighteenth century honor was an important concept. First, it meant that you were your word. You met declared obligations. (Period!) You had an internalized sense of right and wrong.

You owned your mistakes and you fought for your beliefs, especially when they pertained to the greater good. For Washington, there was no higher calling than being a soldier. In his youth he fought many battles for the British Army, hoping to earn his way to becoming a commissioned officer. Most of them he lost; but he learned. When he finally realized that the British generals looked down on him as less-than-officer material at a time when the colonies were becoming restive under the rule of King George, III, he was ready to do his duty and take command of the rag-tag militia of the colonies to fight for freedom from English rule and for self-government of the United States. It was a formidable task. There was no greater fighting force at that time than the British army and navy.

Second, he didn't quit when things got tough. There were several last-ditch, do-or-die feats that he commanded with audacity and grit. One event was crossing the Delaware on a bitter Christmas eve to ultimately win the battle of Trenton-- the crucial first-needed triumph to keep the colonists engaged in the war.

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze, MMA-NYC, 1851 He died in 1799 and his life and work have been scrutinized by many. He did not want power for its own sake. He did not want to be president. He served two terms and passed the baton on to John Adams. King George could not understand how he could take a pass on being, well, a king.

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze, MMA-NYC, 1851 He died in 1799 and his life and work have been scrutinized by many. He did not want power for its own sake. He did not want to be president. He served two terms and passed the baton on to John Adams. King George could not understand how he could take a pass on being, well, a king.The series was produced by presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin who said that "Resilience and humility and empathy” were Washington's chief character traits. He was worried about the emergence of a rancorous partisan divide in our fledgling country. In his farewell address, which was published in newspapers as a letter to the American people, he warned us [about] “the baneful effects of party spirit, of the spirit of revenge, of sectionalism, and the worry that if we endure such things it could lead to foreign influence and corruption.”

Our current electorate who bought the slogan "Make America Great Again," still needs a history lesson from our first most honorable president.

Published on February 19, 2020 11:03

January 12, 2020

Light at the End of the Tunnel

For the past 25 years there has been a national war between so-called education reformers and public schools. Education historian and indefatigable blogger on the topic, Diane Ravitch, has been chronicling the attacks, losses and now, finally, victories through her blog, where she posts up to ten times a day, every day, since April of 2012. In her new book Slaying Goliath: The Passionate Resistance to Privatization and the Fight to Save America's Public Schools, she pulls the disparate threads together and writes a brilliant, page-turner story of this war against public schools for a period that included my 5 grandchildren.

For the past 25 years there has been a national war between so-called education reformers and public schools. Education historian and indefatigable blogger on the topic, Diane Ravitch, has been chronicling the attacks, losses and now, finally, victories through her blog, where she posts up to ten times a day, every day, since April of 2012. In her new book Slaying Goliath: The Passionate Resistance to Privatization and the Fight to Save America's Public Schools, she pulls the disparate threads together and writes a brilliant, page-turner story of this war against public schools for a period that included my 5 grandchildren.Who are the bad guys? Millionaires and billionaires who come from a business background where forces of free-market choices, competition, and new standards create disruption in the market place allowing the best products to rise to the surface. Ravitch names names. We know who they are and they include Bill Gates, Betsy De Vos, and the Walton (Wallmart) families.

Ravitch aptly changes their names from education "Reformers" to education "Disrupters." Measurement is key to determining educational success in the form of high stakes testing that occurs every school year for grades k-12. Right out of the starting gate the Disrupters' premise was wrong-headed and untested.

The methods of this warfare included slamming public schools as "failing" and demonizing teachers while supporting the creation of brand-new charter schools and vouchers to pay religious schools using tax payer money and selling the concept that now parents have "choice." If you knew what it takes to create and sustain a good school, you would know that non-educators with dough are not the people who should be starting one no matter how pure their motives. (I served 18 months on the board of a charter school that is now shuttered.) Politicians from presidents, G.W. Bush and Barack Obama, to local school board members jumped onto the shiny new Disrupter bandwagons. It never occurred to them that America's children were Guinea pigs. Disruption is not healthy for children. Using children to experiment with the profit-motive in education is an insane idea. Where can the profits for investors come from? Real estate (the new schools need space to rent, build or buy), using cheap, young and untrained teachers from Teach for America, and the selling of technology. Education doesn't produce a product that you can sell for a profit. You can't garnish the wages of a state-educated worker. But every time money changes hands, someone's pockets are lined, often illegally, since there is no mandated oversight for charter schools and many opportunities for corruption. Less that 40% of the funding for these new ventures are used for what happens in classrooms. And the Disrupters did not like to discuss that the funding not only came from the wealthiest Americans but also from the local public school budgets, thus short-changing resources for more than 85% of American students.

The collateral damage of this policy of disruption was the destruction of teacher morale and the anxiety that the high-stakes testing put on children. Test prep robbed children of the joy of learning. It made them fearful that if they did not do well on the test, their teachers would be fired. Ravitch's book meticulously cites the damage done in cities and states over the years. It's enough to make your blood boil! About ten years ago, I was invited to speak at Southern Florida University's Education Department. The faculty were steeling themselves to greet the first entering class of FCAT babies, who had taken assessment exams at the end of every one of their 12 years of schooling. Now they were to be trained as teachers. Their professors found them to be passive, docile, and answer-driven, fearful of questions for which they had no answers and tied to using boring texts and worksheets as their main pedagogical tools.

Another example: My grandson, Jonny, who was a very serious student didn't do well on tests. (Currently he is the top student in his electrical engineering class at Buffalo University but still worried about the Graduate Record Exam). He attended a small public school in Western NY state which was not overly scrutinized by the powers-that-be and had a staff that cared about their students. But still they had to adhere to the standards and the testing. When Jonny was in seventh grade I asked him how many of his teachers were having "fun" teaching him. By "fun" I meant that they enjoyed being in the classroom and were present for their students. He thought for a long time before he came up with his sixth grade Language Arts teacher. I concluded that none of his seventh grade teachers were having any fun and I had a follow up question: How did he know they weren't having fun?"Because," he responded, "I'm not learning very much."

Ravitch is very careful to let doubters know how she knows every fact in the book with 30 pages of citations in very small type at the back of the book. In her final chapter, "Goliath Stumbles," she cuts loose with a passionate summation of how the tides are finally turning due to the grass-root rebellions of teachers and parent activists who defeated referendums, politicians, and lobbyists with their strikes, protests, social media organizations and most importantly, their votes. I can imagine how fast and hard she hit those computer keys as she wrote these first glimmers that the tide is turning and humanity and sanity are finally returning to American public schools.

Thanks for the lesson, Diane Ravitch. Many still need it.

Published on January 12, 2020 07:59

December 26, 2019

A Picture Book for the Ages

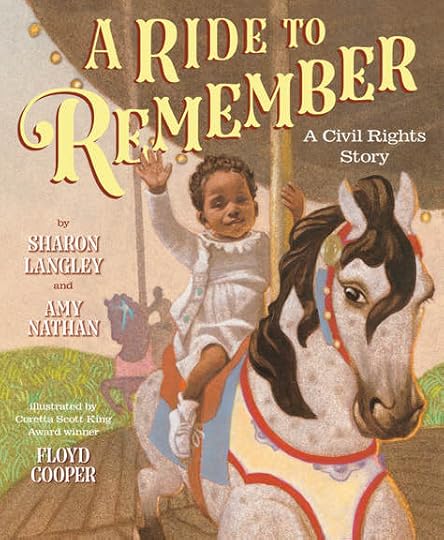

Important history is often made of small moments. On August 23rd, 1963, almost one-year old, Sharon Langley took her first ride on a carousel at the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Baltimore, Maryland. Her father stood beside her to make certain she stayed in the saddle. On the first page of text in A Ride To Remember: A Civil Rights Story, told in the first person by Sharon Langley and award-winning iNK coauthor Amy Nation, a point is made:

"I love carousels.

"The horses come in so many colors--black, white, brown, gray, a honey shade of tan, sunny yellow, fire engine red, or even a soft baby blue. But no matter their colors, the horses all go at the same speed as they circle round and round. The start together. They finish together, too. Nobody is first and nobody is last. Everyone is equal when you ride a carousel"

What follows is a moving story (for 6-9 year olds) of the desegregation of a popular amusement park that had long been for white's only. But Sharon didn't get that ride by accident. It was preceded by a community coming together in protest, on more than one occasion. And four hundred people of all races, even children, were jailed. Coincidentally, (or maybe not) Sharon's ride came on the day Martin Luther King, Jr. was making his "I Have a Dream" speech in Washington.

The illustrations by Floyd Cooper, a Coretta Scott King Award winner, have an appropriate retro feel. They also have a loving softness that belies the potential for violence and hate and projects the arc towards justice. The back matter includes a discussion of Amy Nathan's previous YA book

Round and Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride into the Civil Rights Movement, an engaging read of local history, meticulously researched.

iNK's mission, as a nonprofit, is to show educators that well-written books by top authors make a huge difference in the learning experience of both teachers and students. There are plenty of supportive anecdotes by teachers who have used our books in their classes but what happens when a book is the foundation of an important part of the curriculum of several schools?

Round and Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride into the Civil Rights Movement is now a regular part of the curriculum in 7th grade language arts classes in Baltimore County Public Schools. The teachers have paired the book with other works of black history and culture of that time period including Margot Lee Shetterly's book Hidden Figures and Lorraine Hansberry's play, A Raisin in the Sun. For more information on the use of trade books in the classroom, contact Aimee Hutchison, Resource Teacher, Office of Secondary English/Lauguage Arts, Baltimore County Public Schools: ahutchison@bcps.org

iNK author, Amy Nathan, sums up her book, written for a YA audience:

"The book presents the evolution of the protests at Gwynn Oak over a 9 year period from 1955 to 1963 -- going from low-key picketing just once a summer — to having large numbers of protesters in two major events in July 1963 with mass arrests, showing the evolution in the civil rights movement as a whole, as activists in Baltimore learned from the more successful protests that went on farther South: the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-6), and Lunch Counter Sit-Ins that started in North Carolina (1960), and the Freedom Rides (1961). These more effective tactics. . . . . were: having lots of protesters, keeping the pressure up, getting good TV and newspaper coverage, and, with the Freedom Rides, using mass arrests."

Baltimore is also the home of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture, which had long been involved in educating local school children about local history. Nathan, used the museum as a source when creating the book, which was published in 2011. In 2013-2014 the Maryland State Department of Education's civil rights curriculum asked Nathan to write a lesson on the book that is free to everyone and they field-tested the use of the book. It must have gone well because Baltimore County ordered 2,000 copies and prepared to use it

Publication Date 1/7/2020

Published on December 26, 2019 07:19

December 3, 2019

Excellence for Kids: Free and Online

In my recent post

Why Education Should Always Be Nonprofit

I examined some opportunities for corruption. First, in the building of fortunes, like oil, but also in the establishment of for-profit schools where money is siphoned off by realtors and administrators. The product of education is not a commodity that generates enormous wealth, like oil, but a human being who is capable of contributing to society. So where's the payoff for the individual for-profit investor in the school? It's certainly not in the production of educated individuals. Society at large benefits from that investment.

In my recent post

Why Education Should Always Be Nonprofit

I examined some opportunities for corruption. First, in the building of fortunes, like oil, but also in the establishment of for-profit schools where money is siphoned off by realtors and administrators. The product of education is not a commodity that generates enormous wealth, like oil, but a human being who is capable of contributing to society. So where's the payoff for the individual for-profit investor in the school? It's certainly not in the production of educated individuals. Society at large benefits from that investment.So I started a nonprofit organization to bring the work of the most talented children's nonfiction authors to the classroom. To that end, in 2014 we started publishing the Nonfiction Minute , a FREE daily posting of 400-word essays by top children's nonfiction authors. An audio file accompanies each Minute so that the more challenged readers have access to our content. Millions of page-views later, we caught the eye of Paul Langhorst, the executive of SchoolTube. And today, we have something new to celebrate: We are launching The Nonfiction Minute Channel on School Tube. Each post is the audio file of the author reading his/her Minute and is illustrated with art in a slide show. Paul Langhorst, told me that teachers have been asking for more on quality reading and writing, so here we are. There are links on the School Tube post to the Nonfiction Minute archives so students can read the text of the Nonfiction Minutes if they are so inclined.

In addition, Paul has also given me my own Vicki Cobb’s Science Channel, which is a featured channel under “STEM, Math, Chemistry,” the drop-down menu on the School Tube Home Page. It, too, is free. Here is some information about SchoolTube:

It is just like YouTube, but safe for schools. - verified teachers and their students can join for free. Teachers act as moderators to approve student video uploads, keeping inappropriate videos off their system. Many schools do not give students access to YouTube but SchoolTube is viewable in more than 70,000 schools and gets 30+ million page views a year.It is supported by advertising that has also been approved for children. It will take some time for people to find us—School Tube is 13 years old and is HUGE. But Paul is thrilled with the quality of our work, which he says will make us a BIG FISH in his BIG POND. Like Andrew Carnegie ( who sold a lot of steel) and then spent his fortune by creating of public libraries, making knowledge and excellence available free to the public is not a new idea. But we still need great teachers to guide children towards it. Our contribution is designed to get kids into books, that are not necessarily taught in classrooms but are excerpted for the reading passages in the standardized tests.

Meantime, we retain our nonprofit status. If your organization gives through Benevity.com, iNK Think Tank, Inc. is listed.

Published on December 03, 2019 12:35

November 4, 2019

Why the Lecture?

Before there was Google, before there were books, before there was writing by machine and even before there was writing by hand (with a stylus on a clay tablet), there was the lecture. Thousands of years ago, learned men (not sure if there were any women) who gathered in centers of knowledge, spoke to young audiences to impart their thoughts. In those days, the most important quality of the learners' brains was memory. Students truly listened and learned. In fact,

Socrates was concerned that writing would impair memory

. He feared that writing would weaken memory because you could always review your notes at a later time and might not listen as intently. Listening skills meant verbatim memorization. Brains were different then.

Before there was Google, before there were books, before there was writing by machine and even before there was writing by hand (with a stylus on a clay tablet), there was the lecture. Thousands of years ago, learned men (not sure if there were any women) who gathered in centers of knowledge, spoke to young audiences to impart their thoughts. In those days, the most important quality of the learners' brains was memory. Students truly listened and learned. In fact,

Socrates was concerned that writing would impair memory

. He feared that writing would weaken memory because you could always review your notes at a later time and might not listen as intently. Listening skills meant verbatim memorization. Brains were different then.Last week I gave a lecture to people who lecture-- I spoke at a function for the Optical Society of America at the Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE) at the University of Rochester. My topic was How to Make a Scientist and I billed it as a "conversation" not a lecture. My bona fide is that one of my sons, Josh, is indeed, a scientist--an optical engineer. So, full disclosure, he proposed to the OSA to invite me to speak. Imagine that! I, a children's science book author, have something of value to impart to an august body of higher-ed professors with hard-won scientific skills and thousands of hours of lecturing behind them and degrees upon degrees.

I figured that I'd better start by being entertaining. I described a scientist as a person who:

1. Asks questions about observations.

2. Plays with the environment– play means trying stuff out to see what happens.

3. Looks for causal relationships.

4. Repeats the behavior that demonstrated causal relationships.

5. Starts building concepts based on observations and experiments that suggest other questions and activities.

What kind of person exhibits all these qualities? I showed them a picture of a baby. I then told them that most professional scientists have discovered science by fourth grade and I polled the audience. How many of them knew about science as children? Almost every hand went up. I quoted a distinguished Finnish educator who told me, "Education cannot be rushed. It's a law of nature: It takes nine months to make a baby and thirty years to make an engineer."

Then, through my books, I showed them my process, which I describe in the post "How I Teach STEM." I opened the floor to questions after I had "lectured" for about a half an hour. I was startled at the number and the kinds of questions they asked, mostly about how to engage students who seem to be anything but attentive. But then I recalled that most academics are thrown into classrooms as "teaching assistants" with absolutely no instruction in pedagogy.

Some may be natural teachers but most work under the assumption that if they say it, the student learns it. Besides, the emphasis on the part of the university is on research not teaching. They get away with it because today's top tier students have, for the most part, learned how to learn. Many are already autodidacts

Josh once told me a story about one of his undergraduate TA instructors in optics who was a foreign national, with a heavy accent, which no one could understand. He wrote equations with his right hand as he talked with his back to his students and then proceeded to erase what he wrote with his left hand. The students took notes frantically, understanding nothing, in the hopes that they would discover something in their notes that they could find in a book after the lecture so they could figure what the lecture was about. The only reason for attending the lecture was to learn what content would probably show up on the final exam. The attrition rate for optics majors was 50%.

Lectures can be entertaining, even riveting when there is a great deal prior knowledge on the part of the audience. A learned speaker can shed new light on esoteric subjects that delight as they inform. The speaker can capture an audience by showing his/her own enthusiasm and passion for the content. And the speaker can engage an audience by asking questions of them-- who are they? Why are they here? What are their expectations for this class?

In this information age, the lecture has three main functions:

1. To present content in such a way that it motivates students to want to learn it and will do so on their own after class.

2. To connect students to the importance and value the course has had on the development of knowledge. Why they need to know this stuff.

3. To validate what the students have studied to solidify their own emerging knowledge.

And yes, to preview what will undoubtedly be on the final exam. In all cases, if the professor imbues the lecture with his/her own passions and enthusiasms, if he or she reveals their own humanity, their words from the lectern will not fall on deaf ears. Like writing, itself, it's a skill that can't be taught but it can be learned. It will mean that many professors will have to step out of their comfort zones.

Published on November 04, 2019 04:51

October 20, 2019

How I Teach STEM

Published on October 20, 2019 08:28

October 7, 2019

A Reading-Maker Book Festival

Here I am, for the seventh time, at the annual Chappaqua Children's Book Festival. I'm holding a poster for my two newest books in a series called STEM Play. They are literately "hot-off-the-press" and this was my first view of the finished books. What a thrill! Chappaqua, in Westchester County, NY, is a town that values education and reading and attracts the same kind of crowd at their Festival. Last year we had 7,000 visitors, but there were more this year and it was a joy to meet so many families with the interest and money to invest in their children's education.

Here I am, for the seventh time, at the annual Chappaqua Children's Book Festival. I'm holding a poster for my two newest books in a series called STEM Play. They are literately "hot-off-the-press" and this was my first view of the finished books. What a thrill! Chappaqua, in Westchester County, NY, is a town that values education and reading and attracts the same kind of crowd at their Festival. Last year we had 7,000 visitors, but there were more this year and it was a joy to meet so many families with the interest and money to invest in their children's education. The public schools here are excellent and the students take the standardized tests. Even so it creates anxiety for good readers. At the end of the Festival, Alexandra Siy and I presented a program on "Slaying the Standardized Testing Dragon." We made a bookmark with the help of our pal Jan Adkins. And we prepared a handout with a strategy for creating life-long learners who love to read books. I'm hoping that you find this useful.

iNK Think Tank’s Strategy or “Secret Sauce”*Go to www.nonfictionminute.org*Scroll down the “Categories” on the right to find a topic that interests you.*Choose a Nonfiction Minute to read. If you are not a strong reader, click on the arrow on the player when it is blue and listen to the author read his/her Minute aloud.*Plan to keep reading Nonfiction Minutes on a regular basis. *Click on the T2T icon to see what the Minutes can teach you.*Make a list of the subjects you have to learn at school. *Go to iNK Database and register. Use the database to search for lists of books on the subjects you have to learn about in school. http://inkthinktank.org/search/register.cfm*Go to the library and take out books on those subjects. Read the first paragraph. If the book doesn’t grab you, don’t read it. Pick another. *Only read books you like to read even if they seem hard at first.TO BECOME A READER, YOU MUST READ WIDELY (NONFICTION MINUTES) AND DEEPLY (BOOKS ON SUBJECTS THAT INTEREST YOU).

iNK Think Tank’s Strategy or “Secret Sauce”*Go to www.nonfictionminute.org*Scroll down the “Categories” on the right to find a topic that interests you.*Choose a Nonfiction Minute to read. If you are not a strong reader, click on the arrow on the player when it is blue and listen to the author read his/her Minute aloud.*Plan to keep reading Nonfiction Minutes on a regular basis. *Click on the T2T icon to see what the Minutes can teach you.*Make a list of the subjects you have to learn at school. *Go to iNK Database and register. Use the database to search for lists of books on the subjects you have to learn about in school. http://inkthinktank.org/search/register.cfm*Go to the library and take out books on those subjects. Read the first paragraph. If the book doesn’t grab you, don’t read it. Pick another. *Only read books you like to read even if they seem hard at first.TO BECOME A READER, YOU MUST READ WIDELY (NONFICTION MINUTES) AND DEEPLY (BOOKS ON SUBJECTS THAT INTEREST YOU).Reading is the most intimate way to connect your mind to another person’s mind. In time, reading will become a life-long habit that you cannot live without. The standardized test will become easy. No sweat at all!!!

Published on October 07, 2019 10:32

September 21, 2019

Why Education Should Always Be Nonprofit

On a beautiful, early fall afternoon, I took some Dutch friends of mine on a tour of a local attraction, the Rockefeller estate, call Kykuit (meaning "lookout" in Dutch) for its spectacular vistas of the Hudson River Valley. Now a National Trust attraction, this magnificent edifice, built in 1906, pioneered creature comforts that rival the way we live today ( e.g. it was fully electrified) and houses exquisite art at every turn. As our guide pointed out priceless furnishings, sculptures and paintings, he also kept emphasizing the philanthropy of the Rockefeller family, particularly in medicine and art.

On a beautiful, early fall afternoon, I took some Dutch friends of mine on a tour of a local attraction, the Rockefeller estate, call Kykuit (meaning "lookout" in Dutch) for its spectacular vistas of the Hudson River Valley. Now a National Trust attraction, this magnificent edifice, built in 1906, pioneered creature comforts that rival the way we live today ( e.g. it was fully electrified) and houses exquisite art at every turn. As our guide pointed out priceless furnishings, sculptures and paintings, he also kept emphasizing the philanthropy of the Rockefeller family, particularly in medicine and art. The three generations of Rockefeller families who lived at Kykuit, staffed the house with 10 servants and minions of grounds keepers. Everywhere you look in this magnificent estate you experience the product of loving care, artistry and comfort. The service staff brought the human touch to the daily activities that the family engaged in. Family members used their money to pay creative people. A highlight is the below ground art galleries of Nelson Rockefeller with their extraordinary Picasso tapestries. But the Rockefellers also paid their staff a living wage--Pocantico Village is where you'll find the modest but comfortable homes built for their employees. The wife of one of their gardeners worked for my parents for years as a housekeeper and later as a caregiver. She had nothing but good things to say about her husband's employer. She was an Irish immigrant who believed that there was dignity in service to others. We called her Mrs. Furphy.

Near the end of our tour, as we walked through the carriage house featuring their collection of horse-drawn and motor vehicles of the early 20th century, I couldn't resist from asking our guide a politically incorrect question: "It has been said that behind every great fortune there is a crime. What is your response to that?" Our guide was quick to answer: "John D. Rockefeller Senior committed no crimes because there were no laws restricting the ways he amassed his fortune basically by refining oil into kerosene for lighting homes. He called his company Standard Oil [ESSO became the company's brand by spelling out the initials] because of the reliably high quality of his product. However, many have said that his behavior could be considered unethical at times." Then he segued back to talking about the truly formidable force for good that the Rockefeller philanthropies have been for generations.

A brilliant economist and venture-capital friend of mine once told me, "If you create something of value, you should be able to make money from it." That is the capitalist system. J.D. Rockefeller refined oil to make the best kerosene on the market and bought out all his competitors offering cash or stocks in his company. And if that didn't work, he just lowered his prices and ran them out of business. (Those who took the stock all became multimillionaires.) Laws that stopped the practice of building a monopoly for a commodity were enacted after J.D. Rockefeller and his "robber baron" contemporaries, who shaped the beginning of the industrial revolution, had had their way.

But lately I've been thinking, no! Not everything of value should feed the profit motive. Certainly not education. There should be funding available to pay for high quality public education for the public good but its financial health should not include ways to amass fortunes for the "owners." Who are the money-makers in charter schools and vouchers? The realtors who provide the buildings and the top executives who siphon off exorbitant salaries while paying young, inexperience teachers the least they can get away with while pressing them into services (sometimes custodial) that are not part of their high intensity, exhausting, and sometime profoundly rewarding profession. For-profit charter schools fight against teachers' unions that collectively bargain for a decent wages and working conditions for their members. Excellent teachers work for the love of teaching. That's why merit pay for teachers doesn't make them better teachers. The budget items for a rich educational experience for the students are what usually get cut by for-profit schools in exchange for computers that could bring a virtual tour of, say, Kykuit. Why do private schools command exorbitant tuition? Because they are, for the most part, prepared to create meaningful, non-virtual educational experiences for every student. This means that teachers have the support, both financially and professionally that they need to do their jobs successfully. And that's why excellent teachers will take jobs in private schools although they usually pay lower salaries than public schools.

Most people, who love their work, do not aspire to live like the Rockefellers. We need a middle class who has sufficient income for decent homes and food, health care, education for their children and yes, enough for vacations and recreation. I looked around Kykuit and imagined how much time must have been spent purchasing stuff with status, constantly adding to the collections in their home, changing clothes for every meal, calling a servant to serve tea or to perform some other menial task. Even the recreational facilities were on site. A private "Playhouse" housed a bowling alley and indoor swimming pool. And, of course, there were several outdoor swimming pools, a golf course and tennis courts on the property amidst the formal gardens.

Kykuit is a museum now. I am grateful that I have the education to appreciate its beauty and its history. As a National Trust, it is now a nonprofit for the public good. What do you think might be the take-away of public school students who took a field trip to this family home of obsolete grandeur, art, and splendid self-contained isolation?

I'll bet that they wouldn't trade it for their phones!

Published on September 21, 2019 07:15

September 18, 2019

A Hard Look at a Typical Question on a Standardized Test

wikimedia commons I wrote this post last year and normally don't republish any posts. But this one is an excellent reminder of the insanity of standardized testing as we begin a new year.

wikimedia commons I wrote this post last year and normally don't republish any posts. But this one is an excellent reminder of the insanity of standardized testing as we begin a new year.First, you have to read a paragraph: (Note, this is for a grade 6 test)

The modern wood pencil was created by Joseph Dixon, born in Massachusetts in 1799. When he was thirteen years old he made his first pencil in his mother's kitchen. His sea-going father would return from voyages with graphite in the hull of his ship, which was used simply as ballast, or weight, when there was no cargo to transport. This graphite was later dumped overboard to make room for shipments for export. Joseph Dixon got some of this excess graphite, pounded it into powder, mixed it with clay and rolled it into long strips that he baked in his mother's oven to make the "lead" for his pencil. This dried the "lead" and made it firm. He then put a strip of "lead" between two grooved sticks of cedar and glued them together to make a sandwich. He chose cedar because it is soft, can be easily sharpened, and is relatively free of knots. All you had to do was sharpen the pencil with a knife and it was ready to write.

Then you have to answer the following multiple choice questions:

1. You can tell from the passage that it was important for ships to be

a.) heavy enough b.) fast enough c.)wet enough d.) big enough

2. Dixon got some graphite that had been used to replace

a.)cargo b.)powder c.)clay d.) wood

3. What happened to the graphite that Dixon didn't use?

a.)It was thrown away b.)It was used for ballast c.)It was shipped as an export 4.) It was used to build houses

4. Why did Dixon heat the mixture of graphite and clay?

a) To harden it b.) To melt it c.)To turn it into a powder d) To make it dark.

5. Dixon chose cedar because it was

a.) easy to shape b.) firm c.) long d.) cheap

6. How did Dixon get the "lead" inside the pencil?

a.) He glued it between two pieces of wood. b.) He poured it in when it was melted c.) He slide it into a hole he had drilled.) He rolled it in a mixture of sawdust and glue

7. In this passage the word knots refers to

a.) hard spots in wood b.) difficult problems c.) a measure of the speed of ships d.) tying ropes

Now, here are some questions that might interest you about the test questions.

1. Where did I get this information? From a contract asking permission to use the passage from a book I wrote ( The Secret Life of School Supplies .)

2. What are the chances that the students read the actual book in their test prep? Nil Ever? Close to nil.

3. Did the students find the passage riveting reading? Probably not. It was taken out of context.

4. Why is it important for students to regurgitate information from the passage in their responses? I have no idea. If they have no real interest in the invention of the pencil, if the story isn't interesting enough to repeat to someone else, it is a manufactured trap to give anxiety to students, parents and teachers. It's the previous paragraph in the book that describes the problem that the invention of Dixon's pencil solved that makes the test paragraph more interesting and memorable.

I would hope that the passages selected by the test creators would be stand-alone attention grabbers. But apparently two paragraphs would be too long. FYI, The pencil happened to be an extremely useful invention for land surveyors. They had to be able to write outside with a permanent dry writing instrument, since at that time, most writing was done with quill and ink, which wasn't suited to noting down critical information in the wind and the rain.

Do you think preparing to answer this kind of question is a good use of your time or your students? I can tell you it's not one of my better paragraphs. Maybe, if they had read more of the book, they wouldn't need test prep to get the answers right.

One other thought. I wonder how well I and my colleague authors who have also had excerpts from their books used as reading passages would perform on such a test. Would we ace it? Somehow I think not.

Published on September 18, 2019 21:00

September 16, 2019

The Devils that Make Us Care

Cute little fella, isn't he? In unfettered, expressive prose, Author Dorothy Hinshaw Patent explains how he got the name:

Cute little fella, isn't he? In unfettered, expressive prose, Author Dorothy Hinshaw Patent explains how he got the name:"The devil got its name in the early 1800s, when the first English settlers arrived. Imagine being one of those settlers. Darkness falls over your campsite and you are trying to sleep, when suddenly you hear mysterious, frightening sounds--unearthly screams and shrieks echoing through the forest. The sounds alone frighten you, but then you see movement in the moonlight-- a black creature disappearing into the night. You believe in the existence of the devil...."

And so, the largest carnivore on the islands of Tasmania got a name it didn't deserve. In recent years, it has developed a horrible disfiguring disease that it also didn't deserve called Devil Facial Tumor Disease or DFTD. It was kind of a contagious cancer that almost destroyed some devil populations by as much as 95% in 2005, almost twenty years after it was first detected in 1996.

This was not a case of the "devil got his due." This was an alarm bell to field scientists who understood that the Tasmanian devil was a keystone species. Its loss would cause an overrun of all the animals it fed on thus destroying the balance of nature in its environment. Dorothy Patent was in the fortunate position to have a concerned scientist friend in Australia who offered her the chance to tell the story about saving the Tasmanian devil.

This was not a case of the "devil got his due." This was an alarm bell to field scientists who understood that the Tasmanian devil was a keystone species. Its loss would cause an overrun of all the animals it fed on thus destroying the balance of nature in its environment. Dorothy Patent was in the fortunate position to have a concerned scientist friend in Australia who offered her the chance to tell the story about saving the Tasmanian devil. As the latest addition to the terrific Scientist in the Field series, Saving the Tasmanian Devil: How Science Is Helping the World's Largest Marsupial Carnivore Survive, Patent tells a riveting story of a race against time before a gruesome disease of a wild animal in a faraway land causes its extinction the face of this earth. Coincidentally, we're also learning from this study information that may contribute to our knowledge of cancer in humans.

One of the great values of this book is how Patent learned to know what she needed to know to tell this story. She and her husband went to Australia and Tasmania and met with the concerned scientists working on the problem. It turns out that DFTD is a unique genetic disease with some quirky properties scientists had never seen before. I loved her clear explanation of exactly how the genes from the diseased devils were scrambled into a pattern where pieces of chromosomes became attached to other chromosomes in weird ways.

Meanwhile the reader learns much about the devil and other marsupial mammals of this unique part of the world. The photographs capture the wild beauty of a place barely colonized by humans. Saving the Tasmanian Devil is an epic story from a foreign landscape that catches the heart and inspires the mind. May it find its way into the hands of curious readers from middle school up.

Published on September 16, 2019 11:09

STEM is an acronym for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math, all separate disciplines in history that are now linked conceptually in the acronym, and, hopefully, in curricula. These new books of mine are in a new imprint, Racehorse, for my publisher Skyhorse Publishing. They are the first original books I have created for them, although they have published three other titles of mine that are bind-ups of evergreen subjects that went out of print and now live on as bigger books representing about thirteen individual titles. The Racehorse imprint is on topics in children's books that are trending. Since I have always integrated the STEM disciplines in all of my books about settled science (basic principles of physics, chemistry, and biology), I have to smile. Almost 50 years after the publication of my first breakthrough book, Science Experiments You Can Eat, I'm in the right place at the right time to catch the wave.

STEM is an acronym for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math, all separate disciplines in history that are now linked conceptually in the acronym, and, hopefully, in curricula. These new books of mine are in a new imprint, Racehorse, for my publisher Skyhorse Publishing. They are the first original books I have created for them, although they have published three other titles of mine that are bind-ups of evergreen subjects that went out of print and now live on as bigger books representing about thirteen individual titles. The Racehorse imprint is on topics in children's books that are trending. Since I have always integrated the STEM disciplines in all of my books about settled science (basic principles of physics, chemistry, and biology), I have to smile. Almost 50 years after the publication of my first breakthrough book, Science Experiments You Can Eat, I'm in the right place at the right time to catch the wave.