Vicki Cobb's Blog, page 2

June 15, 2020

A Picture of the Coronavirus at Work

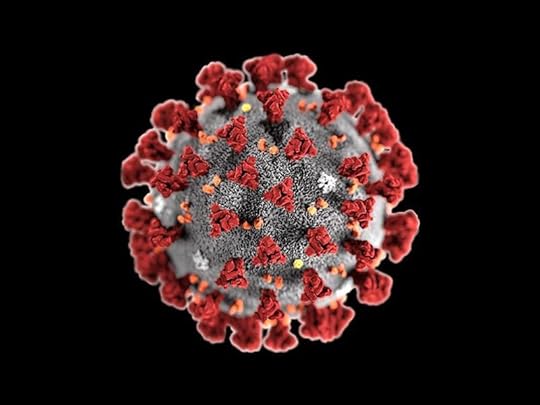

- CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM / Public domain Above is the familiar, iconic electron micrograph of the corona virus that causes the disease COVID-19. Here's what we can learn from the picture. First, it is a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) that shows the three-dimensional surface of the virus. It is a sphere that is extremely small, 1000 times smaller than the cells it invades. We cannot see it under an ordinary microscope that uses visible light, because it is smaller than the shortest wavelength of visible light. It is one thousandth the size of an ordinary cell.

- CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM / Public domain Above is the familiar, iconic electron micrograph of the corona virus that causes the disease COVID-19. Here's what we can learn from the picture. First, it is a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) that shows the three-dimensional surface of the virus. It is a sphere that is extremely small, 1000 times smaller than the cells it invades. We cannot see it under an ordinary microscope that uses visible light, because it is smaller than the shortest wavelength of visible light. It is one thousandth the size of an ordinary cell.Under an electron microscope the image is all gray, (like the background) no color. It is colorized later by people who are trained to recognized structures distinct from a gray background so that that average viewer can easily see them. Viruses have no color because the wavelengths of all the colors of the rainbow (visible light) are longer than the virus. So the color of a structure is chosen to stand out by the colorer. We know its size from the magnification of the electron microscope. An electron micrograph captures an image of a specially prepared specimen in a vacuum. It cannot show us a living cell, only a frozen snapshot.

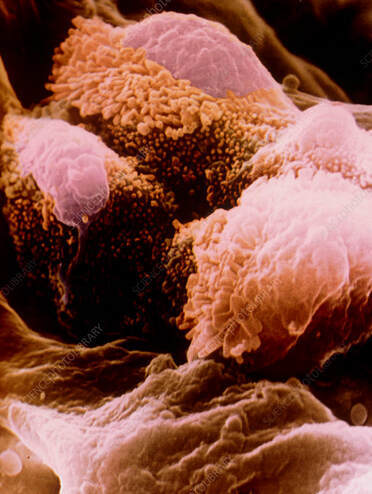

Colored SEM of cells in alveolus of the lung Credit: Prof. Arnold Brody/Science Photo Library This is a scanning electron micrograph of the healthy cells lining an air sac (alveolus) of the human lung. At the center left and top are two type-two cells typically attacked by the novel coronavirus. They are covered with hair-like structures (microvilli) and secrete a substance that that reduces surface tension in the air sac and prevent it from collapsing. The magnification is x 5,100 at the photograph's 6 x 4.5 cm size.

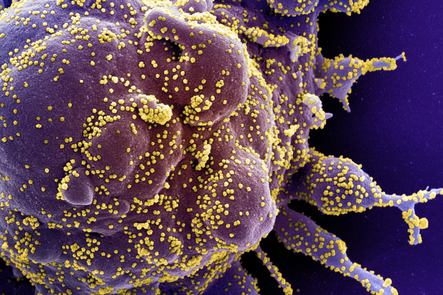

Colored SEM of cells in alveolus of the lung Credit: Prof. Arnold Brody/Science Photo Library This is a scanning electron micrograph of the healthy cells lining an air sac (alveolus) of the human lung. At the center left and top are two type-two cells typically attacked by the novel coronavirus. They are covered with hair-like structures (microvilli) and secrete a substance that that reduces surface tension in the air sac and prevent it from collapsing. The magnification is x 5,100 at the photograph's 6 x 4.5 cm size.  Image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases. This is a colorized scanning electron micrograph of a lung cell infected with the virus the causes COVID-19. They are the yellow dots on the surface of the cell. You can see how small they are compared to the cell, which has many projections to increase its surface area for the exchange of gases (oxygen for carbon dioxide), the crucial job of the lungs to keep us alive.

Image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases. This is a colorized scanning electron micrograph of a lung cell infected with the virus the causes COVID-19. They are the yellow dots on the surface of the cell. You can see how small they are compared to the cell, which has many projections to increase its surface area for the exchange of gases (oxygen for carbon dioxide), the crucial job of the lungs to keep us alive. The spikes on the surface of a COVID -19 coronavirus (you see in the first picture) are proteins that fit like a piece of jig-saw puzzle to receptor proteins on the surface of the host cell. This fools the cell into inviting the infectious enemy through its membrane. Once inside, the coronavirus finds a ribosome, a small organelle that makes proteins from RNA codes specific to the organism. (RNA is a single strand of nucleotides with the same sequence as the organism's DNA) . The coronavirus, which is basically RNA with a protein protective coating, is able to use the replicating machinery of a ribosome to make copies of itself. The newly minted coronaviruses then squeeze through the cell membrane like tiny buds. In the process, it interferes with the functioning of the lung cell to provide us with oxygen.

Meanwhile lots more of the virus are being replicated inside the cell. Upon re-emerging outside the cell, each virus particle is now free to infect other cells in the body and be shed from the person in tiny drops of moisture from speaking, sneezing and coughing.

Self-replication is an essential activity of all living things. Is a virus a living thing? Are there any free-living viruses? All it can do is replicate itself in the cells of a living host, which range from the smallest bacteria to us. It doesn't have metabolism, so it doesn't "eat." As long as it doesn't come across an outside environment strong enough to destroy is complicated molecular structure, it will exist (not "live") as long as it needs to exist until it encounters a receptive host.

It's amazing to see the magnitude of the infection in the microscopic world of a single sick cell.

Published on June 15, 2020 21:00

May 25, 2020

The Birds.....and the Bees

At a time when nature is attacking the human species, it makes sense to look at two other species that have been under attack for many years. First, The Turtle Dove' s Journey: A Story of Migration by Madeleine Dunphy, is a tale of the month-long trip of one small individual turtle dove from his home near London who travels 4,000 miles to winter over in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the back matter, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSBP) began tracking European turtle doves by satellite since 1980, when their population in Europe had dropped by 78% and are still at it, since 1994, with a further decrease to 93%.

At a time when nature is attacking the human species, it makes sense to look at two other species that have been under attack for many years. First, The Turtle Dove' s Journey: A Story of Migration by Madeleine Dunphy, is a tale of the month-long trip of one small individual turtle dove from his home near London who travels 4,000 miles to winter over in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the back matter, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSBP) began tracking European turtle doves by satellite since 1980, when their population in Europe had dropped by 78% and are still at it, since 1994, with a further decrease to 93%.The Turtle Dove's Journey is a picture book, illustrated with quietly stunning art by Marlo Garnsworthy. We see the travels of a single, lone bird as he embarks from Suffolk, England in the fall and flies due south arriving at Mali a month later with stops along the way.

"When migrating, the turtle dove flies at night because it is safer. If he traveled

during the day, predators like falcons and hawks could easily see him. But at night time these predators are asleep."

Thus, the reader is invested in the fate of a single bird, as opposed to a traditional dispassionate description of the migration of many. It is this point of view that gives the story its power. A map of the flight path serves as an index of double-page illustrations depicting and acclaiming the turtle dove's rest stops.

The publisher, Web of Life Children's Books, is dedicated to stories of the fragile ecological dependencies of life on earth. They also published Dorothy Patent's At Home with the Beaver, which I also reviewed.

There have been five extinctions of life over the past 3.5 million years. We are now in the sixth. Survival of the web of life is under constant attack. A Turtle Dove's Journey brings Madeleine Dunphy's focus on a lovely, seed eating bird, who routinely travels great distances for seasonal comforts in home territories 4,000 miles apart.

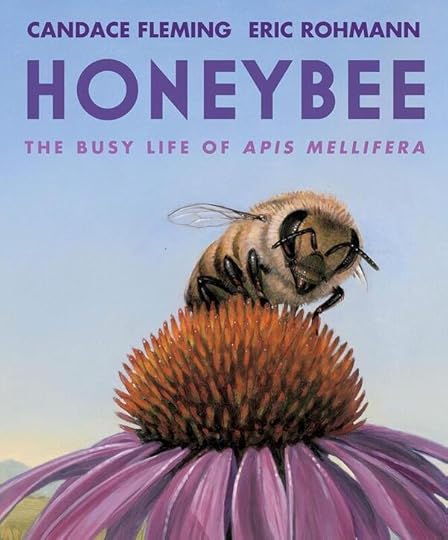

And now for the bees. Honeybee:The Busy Life of Apis Mellifera is a picture book written by Candace Fleming and illustrated by Eric Rohman, created especially for people that don't think of insects as warm, fuzzy, strong, loving and essential workers. (Yes, I'm channeling Andrew Cuomo.) The essential worker part, in the back matter of this biography of a worker bee Apis, was revealed in 2006 when there was a collapse of honeybee colonies, both wild and domestic all over the world-- a pandemic for bees! It impacted "one out of every three mouthfuls of food in the American diet [that] is, in some way, a product of honeybee pollination--from fruits to nuts to vegetables."

A honeybee colony is an intricate cooperative society that is chronicled in the life of a single female worker bee whose job changes every couple of days. Candace Fleming's lyrical prose leading up to a job that involves the act of flying (which we anthropomorphically think of as worthy of aspiration) doesn't happen immediately. The intense, extremely active, slightly-longer-than-a month lifetime of Apis begins with a struggle to get through the wax cap of the cell in which she developed. "Hmmmmm!" hums Fleming's words. "Now what?" the reader wonders.

Flying is delayed for days as Apis cleans up after her "birth," starts gaining strength by eating a lot of stored pollen, taking care of developing bees in the hive's nursery, tending the queen bee, building the comb for the reception of honey, processing incoming nectar from other bees until she is 18 days old and ready to start flying to collect nectar and spread pollen herself. Her first flight is rightfully celebrated with a double page spread featuring Apis, a lone bee over a field of wild flowers.

Her nectar collection and pollen spreading career lasts about two weeks. During this time:

"She has flown back and forth between nest and blossoms, five hundred miles in all.

"She has visited thirty thousand flowers.

She has collected enough nectar to make one-twelfth of a teaspoon of honey."

In the natural order of things, she dies but is replaced by a new worker bee struggling our of her wax cell.

Both Fleming and Rohman are to be commended on this distillation of enormous amounts of meticulous research into lyrical prose and vivid, detailed art that pays homage to an insect whose colonies contribute mightily and essentially to the web of life.

Published on May 25, 2020 07:05

May 12, 2020

Voting and The State of the Union

The United States is hailed by the rest of the world as its most successful democracy. Yes, we are guaranteed great freedoms and we are the most diverse superpower. But, according to iNK author, Elizabeth Rusch, we have a long way to go to become "a more perfect union." Her new book, You Call This Democracy: How to fix our government and deliver power to the people, is an eye-popping exposé of all the ways the wealthy oligarchs have gained overarching power and what can be done by young people to fix it.

The premise of democracy is one person, one vote, majority rules. Simple, no? That is true for all elections in the United States save the one for president and vice president, which is determined by electoral representatives. But there's more, Rusch reminds us: Four times, in our history, popular vote winners lost the presidency. Then she explains not only why but how this can be corrected, not by doing the impossible and adding another amendment to the constitution, but by another method entirely called the "National Popular Vote" interstate compact. In her highly readable book she says:

"The compact will take effect once states representing a total of 270 electoral

votes--the number needed to win the presidency--have signed on. The endeavor

is two-thirds of the way there, with just seventy-four more electoral votes needed.

Efforts are afoot in a dozen or so states, which could get the tally to the magic 270."

Wow! I learned something new. And I continued to learn, in subsequent chapters, about specific problems stymieing many voters from making their vote count. These include: geographically redistributing party votes (gerrymandering), under-representation of populous states in the Senate, dark money influencers (lobbyists and legal contribution loopholes), lying with impunity for politicians, voter suppression, votes denied to the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, where Americans are stateless, and more.

But this book is not just a litany of woes. As Rusch says in her introduction:

"I admit, working on this book often made me angry--even outraged--when

I saw clearly how some aspects of our democracy hurt fellow citizens. But my

research has made me hopeful, too. Countless people, young and old, are

already working to form a more perfect union......this book is, ultimately,

a book of solutions."

Elizabeth Rusch, whose work I know from her many accurate and accessible science-related children's book, (sometimes on the same subjects that I, too, have explored) is extremely qualified to give me a civics lesson. (What ever history and civics I know has come to me independently of my formal education.) She first became interested in politics from an eighth-grade trip to the U.S. Senate. She has a master's in public policy from U. C. Berkeley and has served as a Jacob K. Javits Fellow in the U.S. Senate. In keeping with her target audience of young adult readers, she has also established an interactive website: https://www.youcallthis.com/ where they can find actionable items in their own states.

You Call this Democracy? is a how-to book for saving what is valuable in our country and a practical, actionable guide to young people who are tasked with creating a brighter future out of the immense challenges we now face in the wake of this pandemic.

It is a timely and very valuable addition to home libraries of teen-agers and their parents.

Published on May 12, 2020 21:00

May 7, 2020

A Candidate for a Child's Home Library

In my last post, I quoted a literacy statistic for a children's home library, "Children growing up in homes with at least twenty books get three years more schooling than children from bookless homes, independent of their parents’ education, occupation, and class." A children's home library contains books that, by definition, will be read more than once. Roxie Munro's glorious adventure under water on a coral reef,

Dive In: Swim with Sea Creatures at Their Actual Size,

is a perfect candidate.

In my last post, I quoted a literacy statistic for a children's home library, "Children growing up in homes with at least twenty books get three years more schooling than children from bookless homes, independent of their parents’ education, occupation, and class." A children's home library contains books that, by definition, will be read more than once. Roxie Munro's glorious adventure under water on a coral reef,

Dive In: Swim with Sea Creatures at Their Actual Size,

is a perfect candidate. Dive In is enticing on so many levels. As someone who has had the memorable experience of snorkeling at the Great Barrier Reef, once was not enough but once is all I got. Munro's book powerfully creates the experience. You are immersed and absorbed, never leaving the sea, viewing 29 of the gorgeous, quirky, fantastical inhabitants of coral reefs. It deserves to be revisited time and time again.

Did you ever hear of a spotted cleaner shrimp or a longsnout seahorse or the queen triggerfish, to name a few? And what's that gray thing that starts looming in the background on 15,16, 17, 18 and folds out into two double-spreads on pages 19-22 to reveal a reef shark that is 8 feet long? (Measuring that critter, alone, is worth owning the book.)

This is a book that commands study and involvement that goes way beyond the five-minute bedtime read. Munro includes a simple fact or two for each critter that are gems:

"The common octopus is a mollusk, as are snails, clams, and squids. Like a squid,

an octopus also changes colors and patterns to camouflage itself. An octopus has

excellent vision and a large brain, and is considered the most intelligent,

invertebrate. It even uses tools to build its den, which might feature a door that

opens and closes!"

My kid-like curious brain is teeming with questions to know more. If it's a mollusk, where's its shell? How many colors can it be? How do we know that? What does its eyes have to do with the size of its brain?

The back-matter reveals a key to the 29 different species as a "walk in the park" diagram including the relative sizes depicted as actual size in the book. Yep, there's the reef shark, taking up space in the middle. And the end papers feature coral reefs of the world, including the one I dove into.

Roxie Munro brings the skills of a fine artist and the discipline of a diligent nonfiction author to revealing a complex and glorious ecosystem currently under attack from global warming.

If Dive In is the first book on coral reefs in a child's library, it will not be the last.

Published on May 07, 2020 12:21

May 5, 2020

The Home Library Background

Have you noticed the background behind many pundits who are broadcasting from their homes? Some, of course, use green screens so that are speaking in front of the capitol building or a cityscape of Washington DC. I haven't taken a tally, but it seems as if most of them are speaking in front of books on a shelf. It is done unconsciously, since a home library is a repository security- blanket of accurate, vetted reference material that is not easily found with Google

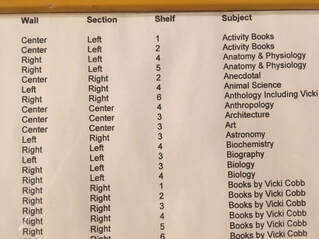

Have you noticed the background behind many pundits who are broadcasting from their homes? Some, of course, use green screens so that are speaking in front of the capitol building or a cityscape of Washington DC. I haven't taken a tally, but it seems as if most of them are speaking in front of books on a shelf. It is done unconsciously, since a home library is a repository security- blanket of accurate, vetted reference material that is not easily found with GoogleI took a picture of part of my home library, above. I am not a neat person, yet, years ago, I had an assistant, Ned Stuart, who took it upon himself to organize my books, which he arranged by category and assigned a permanent place on one of three walls of bookcases. Note that the right wall shelves (not in the picture) have books written by me. The main purpose of this incredible organization is that I can find what I'm looking for. Mine, as it is for many educated people, is a working library. I read a lot of fiction, but I don't have room in my working library for more than a shelf of fiction.

The top part of the framed directory to my three-walled home library as organized by Ned Stuart. The books that I return to over and over again are about science. Some books are from college and grad school. Some are books I bought as reference when researching a new project. There are travel books, cook books, even some history books. Below is a book from my freshman year at the University of Wisconsin. It was the book that made me a scientist and is now spineless.

The top part of the framed directory to my three-walled home library as organized by Ned Stuart. The books that I return to over and over again are about science. Some books are from college and grad school. Some are books I bought as reference when researching a new project. There are travel books, cook books, even some history books. Below is a book from my freshman year at the University of Wisconsin. It was the book that made me a scientist and is now spineless.

Some books have been added since Ned did his work but I could always find a place to squeeze them in, even if they had to be sideways.

Some books have been added since Ned did his work but I could always find a place to squeeze them in, even if they had to be sideways. A few years ago I heard that new homes are being built without bookshelves. My grandchildren are doing their college work online. I just listened to an audiobook on a subject I need to know more about. I enjoyed it but it's still faster to scroll through a printed book to find what you noted on first read and what you didn't remember you were looking for that turns out to be a gem. People who have home libraries undoubtedly had a home library of books as children. Studies have shown that:

The single most significant factor influencing a child’s early educational success is an introduction to books and being read to at home prior to beginning school. National Commission on Reading, 1985 Having books in the home is twice as important as the father’s education level. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 2010 The only behavior measure that correlates significantly with reading scores is the number of books in the home. The Literacy Crisis: False Claims, Real Solutions, 1998 An analysis of nearly 100,000 U.S. school children found that access to printed materials is the "critical variable affecting reading acquisition." JMcQuillan, J. (1998). The Literacy Crisis: False Claims, Real Solutions.Heinemann. Children growing up in homes with at least twenty books get three years more schooling than children from bookless homes, independent of their parents’ education, occupation, and class. Evans, M. D., Kelley, J., Sikora, J., & Treiman, D. J. (2010). Family scholarly culture and educational success: Books and schooling in 27 nations. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28(2), 171-197. There is a lot more on the site I reference.

In this time of forced reflection, I find comfort that so many smart people with opinions on TV have their books behind them. Their books are not for show business. They are an organic part of who they are, thoughtful people who have learned from past generations of thoughtful people who wrote books.

Published on May 05, 2020 21:00

April 4, 2020

Just Because It’s a Proven Fact, Doesn’t Mean They’ll Believe It

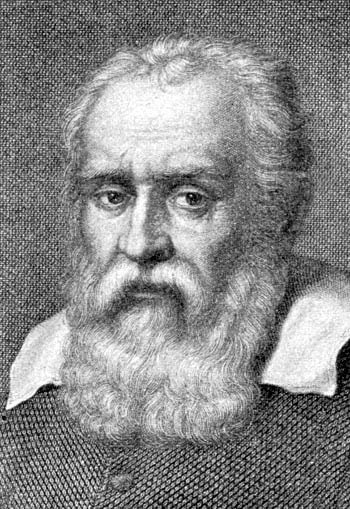

Galileo Galilei Wikimedia Commons Recent resistance by some people who refuse to believe the science that predicts the course of covid 19 through a population, reminded me of a post I wrote several years ago that bears revisiting.

Galileo Galilei Wikimedia Commons Recent resistance by some people who refuse to believe the science that predicts the course of covid 19 through a population, reminded me of a post I wrote several years ago that bears revisiting.When Galileo discovered the moons of Jupiter in his telescope, he couldn’t wait to share it with the world. So, in 1610 he hurriedly rushed The Starry Messenger, the story of his discovery, into print. Now in those days they didn’t have talk shows. So, to promote his book, Galileo took his telescope to dinner parties and invited the guests to see Jupiter’s moons for themselves. Many refused to look claiming that the telescope was an instrument of the devil. They accused Galileo of trying to trick them, painting the moons of Jupiter on the end of the telescope. Galileo’s response was that if that were the case they would see the moons no matter where they looked when actually they could see them only if they looked where he told them to look. But the main objection was that there was nothing in the Bible about this phenomenon. Galileo’s famous response: “The Bible shows the way to go to heaven, not the way the heavens go.”

Galileo is considered the father of modern science, now a huge body of knowledge that has been accumulated incrementally by thousands of people. Each tiny bit of information can be challenged by asking, “How do you know?” And each contributing scientist can answer as Galileo did to the dinner party guests, “This is what I did. If you do what I did, then you’ll know what I know.” In other words, scientific information is verifiable, replicable human experience. Science has grown exponentially since Galileo. It is a body of knowledge built on an enormous quantity of data. And its power shows up in technology. The principles that are used to make a light go on were learned in the same meticulous way we’ve come to understand how the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have risen over the past 100 years leading to ominous climate change or that Darwin was right, and living species are interconnected “islands in a sea of death.”

Yet there are many who cherry pick science—only believing its findings when they agree with them.

(Documented proof doesn’t fare much better. Despite the publication of President Obama’s much questioned birth certificate, there is still a percentage of the population that refuses to believe he was born in the USA.)

Nonfiction authors take pride in the rigors with which we verify the accuracy of the content we write about. We enjoy the satisfaction of knowing we are dealing with facts and when the facts are in dispute, we are careful to mention that that, too, is a fact. Yet, there are still those who are not convinced.

What’s going on here? Believe it or not, science has taken a look at so-called “motivated reasoning” where people rationalize evidence that is not in keeping with deeply held beliefs. Here are some of the findings:

A large number of psychological studies have shown that people respond to scientific or technical evidence in ways that justify their preexisting beliefs.Many people rejected the validity of a scientific source because its conclusion contradicted their deeply held views.Head-on attempts to persuade can sometimes trigger a backfire effect, where people not only fail to change their minds when confronted with the facts—they may hold their wrong views more tenaciously than ever.The problem is arguably growing more acute, given the way we now consume information—through the Facebook links of friends, or tweets that lack nuance or context, or “narrowcast” and often highly ideological media that have relatively small, like-minded audiences. Those basic human survival skills of ours, says Michigan’s Arthur Lupia, are “not well-adapted to our information age.”

And finally the conclusion: “If you want someone to accept new evidence, make sure to present it to it in a context that doesn't trigger a defensive, emotional reaction.”

In other words, sometimes a direct approach to the facts is NOT the way to go.

So keep an open mind about this.

Published on April 04, 2020 06:51

March 27, 2020

Why Science, Anyhow?

This quote from the Washington Post is very frightening, "In recent days, a

growing contingen

t

of Trump supporters have pushed the narrative that health experts are part of a deep-state plot to hurt Trump’s reelection efforts by damaging the economy and keeping the United States shut down as long as possible. Trump himself pushed this idea in the early days of the outbreak, calling warnings on corona virus a kind of “hoax” meant to undermine him."

This quote from the Washington Post is very frightening, "In recent days, a

growing contingen

t

of Trump supporters have pushed the narrative that health experts are part of a deep-state plot to hurt Trump’s reelection efforts by damaging the economy and keeping the United States shut down as long as possible. Trump himself pushed this idea in the early days of the outbreak, calling warnings on corona virus a kind of “hoax” meant to undermine him."For these ignorant people let me try to explain the most important aspect of science as far as life and death is concerned. Our understanding of weather and violent storms has been growing incrementally and exponentially over the years. First, we used science to understand the properties and behavior of water and air-- the physical components of weather. We had to understand the effect of temperature on the volume and pressure of gases, the effect of heat energy on the evaporation of water and wind speed. There were many variables to measure.

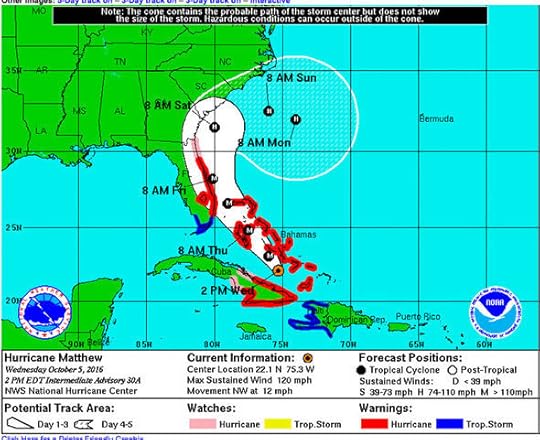

On September 8, 1900, the deadliest hurricane in American history, a category 4 storm hit Galveston, Texas and flattened the town. The death toll was between 6,000 and 12,000. The folk in Galveston never saw it coming. Since then the National Hurricane Center has been collecting data, repeatedly measuring the air pressure, wind speed, humidity, and temperature of low pressure areas as they develop into spinning storms and gain strength to become hurricanes aimed towards our shores. These data are use to create mathematical models that can be used to predict the probability of a developing storm to make landfall, where, approximately, it will happen, when and how strong it will be. The picture above shows the "cone of probability" for hurricane Matthew before it hit. It told the people within the cone to prepare for the storm with enough advance warning for them to do so. People in Florida believe in the science because many have paid the price for ignoring it.

Epidemiologists have collected years and years of data on pandemics. They, too, have models that predict possible outcomes. When it comes to contagious diseases, for which there are no know vaccines or medicines, extreme changes in social behavior and apparel are required. The kinds of stock-piling of PPEs, ventilators, and other equipment for hospitals should have started when patient zero was identified in China. But China didn't do it and didn't let the rest of the world know. So now we know. It is coming as surely as Matthew hit Florida.

Science cannot predict exactly what will happen with the spread of Covid 19 because there are so many variables. But it is here. It is spreading. If you don't believe in the validity of the scientific handwriting on the wall, science doesn't care. And you may be dead before you understand that you were wrong.

Published on March 27, 2020 12:34

March 20, 2020

Live-Streaming Authors Next Week

Our "sheltering in place" has given the authors of iNK Think Tank a wonderful opportunity to reach out to our readers with live-streaming programs through the Center for Interactive Learning and Collaboration. Here's the link to all the programming for next week.

Our "sheltering in place" has given the authors of iNK Think Tank a wonderful opportunity to reach out to our readers with live-streaming programs through the Center for Interactive Learning and Collaboration. Here's the link to all the programming for next week. Here's the schedule for iNK author presentations:

March 24, STEM day, Kerrie Hollihan will present "Plague & Isaac Newton’s Wonder Years" at 2:45 PM EDT

March 27 at 12.45 EDT I will be presenting Slaying the Standardized Testing Dragon: Test Prep that's FUN!

March 27 at 2 PM EDT, Our own Jan Adkins, who drew the above picture will present: Tool Physics: Basic Machines in Your Tool Box

If you register, you can watch the recording later, at your convenience. As soon as I know the programs for the week of March 30, I'll post them here.

Published on March 20, 2020 07:45

February 28, 2020

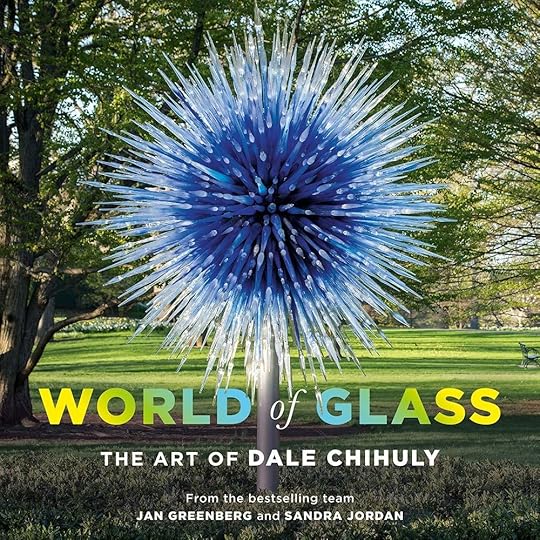

The Maestro of Glass

Glass is an amazing material! It is transparent, can be delicate and easy to shatter or it can be strong, it can be colored and be manipulated to become any shape an artist or craftsperson desires. It is mostly sand with some other chemicals mixed in, depending on what it will be used for. In order to change its shape, it must become a liquid and that requires extremely high, red-hot temperatures--2800°F (1500°C). Working with glass requires skills and respect. Expect failure from shattering (never mind, it can be remelted) and always the danger of serious burns.

Glass is an amazing material! It is transparent, can be delicate and easy to shatter or it can be strong, it can be colored and be manipulated to become any shape an artist or craftsperson desires. It is mostly sand with some other chemicals mixed in, depending on what it will be used for. In order to change its shape, it must become a liquid and that requires extremely high, red-hot temperatures--2800°F (1500°C). Working with glass requires skills and respect. Expect failure from shattering (never mind, it can be remelted) and always the danger of serious burns. Dale Chihuly is a visionary who has mastered the manipulation of glass to create art. His life and work are captured in World of Glass: The Art of Dale Chihuly by the award-winning team of iNK author Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan. In this biography, a first for young people, Chihuly comes alive as an extraordinarily bold person who was hooked on glass the first time he blew a bubble in a glob of molten glass at the end of a steel pipe. If he twirled the molten bubble of glass it widened into a disk. And he could add color to the molten glass by rolling it in shattered glass color sticks. Chihuly has created distinctive glass sculptures that are sometimes massive, brilliantly colored and as eye-catching as they are light catching.

His works begin with an imaginative sketch on paper. He has a team of artisans to help him create his vision, which took a hit when he lost one eye by going through a windshield in an automobile accident:

" 'There was no despair because I just felt so lucky that I didn't lose both my eyes.' Instead of an artificial eye, he put on a swashbuckling black eye patch. It became one of his trademarks."

The authors describe how this loss, which cost him depth perception, and the physicality of working quickly to shape molten glass led him to forming a team of glassblowers who could create his vision:

"After dislocating his shoulder in an accident while body surfing, Dale finally gave up blowing glass. He assumed the role of director making drawings in the hotshop to pass along ideas to his team. His ability to lead as well as to spot talent revitalized him."

World of Glass is a beautifully produced book, lavishly illustrated with full colored photographs and including a double-wide page to be unfolded, emphasizing the scope and power of Chihuly's work. Greenberg and Jordan had personal access to the Maestro himself, as well as his team. The back matter includes a list of places where you can see Chihuly's masterpieces for yourself. Only then can you truly marvel at the scale of his work.

Publication date: May 12, 2020

Published on February 28, 2020 21:00

February 26, 2020

An Outstanding Webinar Experience

From time to time, over the years, I sign up to attend a webinar. One was called "The Non-Lecture Lecture." There was a speaker (lecturing) and a chat going on simultaneously. It involved multi-tasking reading the chat, answering the chat, listening to the speaker as he chuckled reading the comments. I lasted five minutes as a participant. But it was such a phenomenon that I watched to the end as the many participants finally clicked on an icon that gave the speaker a virtual round of applause.

From time to time, over the years, I sign up to attend a webinar. One was called "The Non-Lecture Lecture." There was a speaker (lecturing) and a chat going on simultaneously. It involved multi-tasking reading the chat, answering the chat, listening to the speaker as he chuckled reading the comments. I lasted five minutes as a participant. But it was such a phenomenon that I watched to the end as the many participants finally clicked on an icon that gave the speaker a virtual round of applause. As a person conditioned to watching talking heads on TV, I always found these webinars lacking personalities and production value. But today was different. I think Education Week has hit on a format that allows for REAL audience participation in REAL Time. The topic for the discussion is above. The conversation was divided up into six areas with a virtual "booth" in the virtual "lobby." There was a different question to chat about in each booth. That meant I could enter a chat room, click on the green "chat" button, read what others were saying and add my two cents where I felt I could make a contribution or add support. This allowed me to find people who were saying things that interested me.

At the end, there was a live-streamed video discussion from each editor who headed up a virtual booth. One of them actually quoted something I had written! How 'bout that! It also allows the conversations to hang around in their archives, which you can refer to later.

Of course the skills you need to do this well are reading and writing. I do that every day so participating was easy for me. I think that this format is a real innovation. It allows individuals to fully have their say in real time but also in their own time and according to their own interests.

If these coming webinar summits interest you, check out the new Education Week. It is really exciting to see a novel use of technology coming from an educational source where individual voices can be captured and heard.

Published on February 26, 2020 12:29