Cody Cook's Blog, page 22

July 29, 2018

My latest book Fight the Powers is available for pre-order on Kindle!

July 7, 2018

PODCAST: Cantus Firmus at the Movies Ep. 12 – Saving Mr. Banks (w/ Dr. Andrew Graham)

Dr. Andrew Graham was my guest for a discussion about the 2013 film Saving Mr. Banks. Dr. Graham’s background in counseling shed some light on how this film about Walt Disney’s tense negotiations for movie rights with Mary Poppins author P. L. Travers depicts relationships between parents and children. We also talked about narratives of redemption and why our need for them is so deep and universal.

RELATED: PODCAST: Cantus Firmus at the Movies Ep. 10 – The Night of the Hunter (w/ Bridget Nelson)

Dr. Graham is a licensed mental health counselor, nationally certified counselor, and board-certified professional Christian counselor providing professional counseling and consulting from a Christian perspective. He serves as the Chair of Counseling at Hobe Sound Bible College and as adjunct faculty at several other undergraduate and graduate institutions. Dr. Graham and his wife Lisa live in Hobe Sound, Florida with their 8 children.

Audio:

http://www.cantus-firmus.com/Audio/20180706-CFATM-Ep12-SavingMrBanks(wDrAndrewGraham).mp3

Music:

“Octagon Pt 2” by Polyrhythmics. Licensed under CC BY 3.0

http://www.needledrop.co/wp/artists/polyrhythmics/

July 1, 2018

Patreon Exclusive Podcast Preview – Reading the Prodigal Son Through Western Eyes / Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi

This is the eighth Patreon-only podcast I’ve done, and to give some of the free podcast subscribers a taste of what I do on Patreon, I’ve decided to let them hear this one as well. If you enjoy this episode and want to hear more, as well as get behind the scenes updates of new book projects and free access to digital copies of my books, and even paperback at the higher tier, you can visit www.patreon.com/cantusfirmus

The topics for this podcast include a prominent feature of Jesus’ famous prodigal son parable that Americans tend to miss and my reflection on Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi. Was Luke right to isolate himself from the force and seek to destroy the Jedi way?

Audio Download:

http://www.cantus-firmus.com/Audio/20180701-PatreonProdigalSonandStarWarsEpVIII.mp3

Music:

“Kitchen Suite” by Spiedkiks.

June 17, 2018

PODCAST: Post-Enlightened – Friedrich Nietzsche’s Challenge to Christian Belief

My wife Raven joins me for a reading from a chapter in my book Post-Enlightened: Reflections on Two Hundred Years of Anti-Christian Writing from Thomas Paine to Richard Dawkins. The book can be purchased on paperback or for Kindle at Amazon.com—and for a short time, you can get it on Kindle for free—from Sunday, June 17 through Thursday, June 21.

Post-Enlightened examines the trajectory of anti-Christian writing after the Enlightenment period, beginning with Thomas Paine and ending with Richard Dawkins. It looks at the underlying assumptions in these writings and demonstrates many of their flaws.

The reading is from my chapter on philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s ideas such as the death of God, the will to power, and Christianity as a “slave morality.” If you are intrigued by this reading, please get a hold of the book!

Audio:

http://www.cantus-firmus.com/Audio/20180616-PostEnlightened.mp3

Music:

“The Itis” by Polyrhythmics. Licensed under CC BY 3.0

http://www.needledrop.co/wp/artists/polyrhythmics/

June 16, 2018

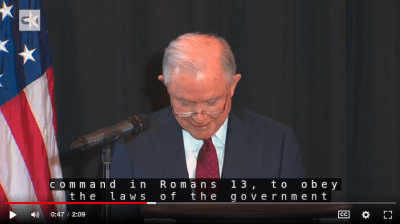

Can Romans 13 be used to justify government oppression?

The following is a modified excerpt from a book I’m in the process of completing about the relationship between demonic and political powers as expressed in scripture. In light of recent events, it seemed appropriate to post it now.

“Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment” (Romans 13:1-2, ESV).

To understand Romans chapter 13, you’ll need to read chapter 12:

“Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord'” (Rom. 12:19-21 ESV).

Paul is here quoting Deuteronomy 32, one of a number of biblical passages which tell us that the nations have been given up to demonic powers but that God’s special people belong to Him alone. In the context of the original verse Paul cited, God is speaking about punishing pagan nations like Rome for their wickedness and mocking their gods who could not protect them:

“For they are a nation void of counsel, and there is no understanding in them . . . For their rock is not as our Rock; our enemies are by themselves . . .Vengeance is mine, and recompense, for the time when their foot shall slip; for the day of their calamity is at hand, and their doom comes swiftly” (Deuteronomy 32:28-35, ESV).

Paul then paradoxically writes in Romans chapter 13 that Christians should be subject to the state because authorities are instituted by God. As a result, “rulers are a not a terror to good conduct,” and if you “do what is good, and you will receive his approval” (13:3, ESV). However, this sounds hopelessly naive on a surface reading. It also flies in the face of what Paul himself knew and experienced.

To begin with, Paul was a Jew in a land which had been occupied by a series of pagan oppressors. In addition, the epistle to the Romans was written in the mid-50s, meaning that Paul’s experience of being unjustly beaten with rods by magistrates in Philippi (see Acts 16) and his public shaming of those same magistrates was more than five years in the past. Not only that, but prior to his conversion he himself had been given the authority to oppress and kill Christians. After his conversion, he would have understood that his sinless Lord and savior had been crucified by the very rulers whom he claimed “are not a terror to good conduct.”

There is no doubt that Paul was aware of the fact that power is often corrupt and does not do what it is supposed to do. This suggests one of two possibilities, though they aren’t mutually exclusive—Paul may have been expressing a best case scenario of what rulers ought to do, though often do not, or, as T. L. Carter suggested, he may have been writing ironically.

Carter establishes the use of irony as a writing practice in the ancient world and also gives a rationale for its use in this passage—to communicate a message to his intended audience which the authorities, if they got hold of the letter, would not have perceived. The authorities would have been flattered by this portrayal of themselves, though many in Paul’s intended audience would have known from personal experience that in practice those in power often did not behave in such a way. After all, these were not voters who had a say in their leaders’ policies, but subjects who had to decide whether it was better to show love to their oppressors or to respond with violence.

Carter also notes that defenders of the traditional view of this passage highlight parallels between it and the deutero-canonical book of Wisdom, which claims that dominion is given to rulers by God. But if this is the inspiration for Paul’s words here, they must be read along with the words immediately following:

“though you were ministers of his kingdom, you did not judge rightly, and did not keep the law, nor walk according to the will of God, Terribly and swiftly he shall come against you, because severe judgment awaits the exalted—For the lowly may be pardoned out of mercy but the mighty shall be mightily put to the test” (NABRE, Wisdom 6:4-6).

That Paul would allude to a writing to support his apparent contention that rulers are instituted by God and only do what is good—even though it actually seems to contradict it—also suggests that a more tongue-in-cheek meaning of this passage was intended by Paul.

The hidden message, for those who knew enough about scripture and popular Jewish writings, was that it is the duty of the magistrate to reward those who do good, but if he instead punished them he would in turn be punished by God for abusing his authority.

In summation, that state does not always do good or serve its divine purpose.

But what are we to do when this is the case? For one, we leave wrath to God and eschew violence against it (12:19). And when it commands of us what is evil, we must follow the apostolic wisdom:

“But Peter and the apostles answered, ‘We must obey God rather than men’” (Acts 5:29, ESV).

T.L. Carter, The Irony of Romans 13, Novum Testamentum XLVI, 3

ibid

June 10, 2018

PODCAST: From Babel to Pentecost – How Jesus Broke Down Racism and Nationalism to Make One New People

In this episode I talked with my friend Jackson Ferrell about how the events of Pentecost in Acts chapter 2 point back to the story of the tower of Babel to show that God has undone the distinctions of race and nationality through Christ’s defeat of the demonic powers behind the nations. I hope your ears have seatbelts on them, because we’re about to take them for the ride of their lives…

Jackson can be found writing dope posts about the Bible every weekday at www.chocolatebook.net

Audio:

http://www.cantus-firmus.com/Audio/20180608-FromBabelToPentecost.mp3

Music:

“The Itis” by Polyrhythmics. Licensed under CC BY 3.0

http://www.needledrop.co/wp/artists/polyrhythmics/

June 4, 2018

PODCAST: Cantus Firmus at the Movies Ep. 11 – Shadowlands (w/ Dr. David Baggett)

In this episode, I spoke to Dr. David Baggett about the 1993 Richard Attenborough film Shadowlands. Shadowlands is a film about the Christian thinker C.S. Lewis’ relationship with Joy Davidman and his emotional and spiritual struggle of loss after she is diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Dr. Baggett is a professor of philosophy in the Rawlings School of Divinity at Liberty University. Author or editor of over a dozen books, he’s the executive editor of MoralApologetics.com. He works in the areas of philosophy and popular culture, philosophical theology, philosophy of religion, ethics, and moral apologetics. His most recent book, co-written with his wife Marybeth Baggett, is entitled The Morals of the Story: Good News about a Good God. He’s also contributed to or edited the books Hitchcock and Philosophy, Harry Potter and Philosophy, and Philosophy and Joss Whedon–which is part of why I thought he’d be a great guest for this podcast.

Audio:

http://www.cantus-firmus.com/Audio/20180603-CFATM-Ep11-Shadowlands(wDrDavidBaggett).mp3

Music:

“Octagon Pt 2” by Polyrhythmics. Licensed under CC BY 3.0

http://www.needledrop.co/wp/artists/polyrhythmics/

May 8, 2018

How Did the Pentateuch Come About?

In a recent article series, I gave a broad history of the development of the documentary hypothesis–the view of most critical scholars about how the Old Testament came together over time by combining various sources. In this article, I wanted to discuss in more detail the arguments these scholars have made to support the hypothesis.

David Noel Freedman’s article in the Anchor Bible Dictionary gives a standard critical account (often referred to as the Documentary Hypothesis) of the Pentateuch’s (the first five books of the Bible, also known as the Torah or the books of Moses) composition:

“The Torah was composed by a number of authors. The originally separate works of these authors were combined in a series of editorial steps into a continuous, united work. The full process of composition and editing, from the earliest passage in the Pentateuch to the completion of the work, took approximately six centuries (11th to 5th century B.C.).”

Evidence for the Documentary Hypothesis

What reasons does he give for supporting such a hypothesis? Here is a summary of his ten evidences:

1. Doublets within the text. When it appears that the same story is being told twice, this might mean that two different versions of the same story have been edited into one work. The classic example suggested of such a doublet is Genesis 1:1-2:3 and Genesis 2:4b-25.

2. Differing terminology. The classic example of this is that sometimes in the Pentateuch (and throughout the Old Testament) God is referred to as Yahweh (the J or Jahweh source) and others times as Elohim (the E source).

3. Contradictions. An example of contradiction supposedly pointing to different authorship builds upon the previous two examples: “The order of creation in the P [allegedly in Genesis 1] account is plants, then animals, then man and woman; but in the J creation account [allegedly in Genesis 2] the order is man, then plants, then animals, then woman.”

RELATED: PODCAST: A PRIEST AND A DEUTERONOMIST WALK INTO A BAR – THE DOCUMENTARY HYPOTHESIS

4. Characteristics of each group of texts. Once one has a broad view of the distinct texts which the hypothesis contends have been brought together in the Pentateuch (identified as J, E, D, and P sources), one may begin to discover characteristics within those sources. For instance, Freedman claims that there are no angels, dreams, talking animals, or anthropomorphic language used of God in P. Similarly, the tabernacle is mentioned over two hundred times in P (the “priestly” source) but never in J or D and only three times in E.

5. Narrative flow. One example Freedman states is that if you take the alleged J source out of the flood story (Gen 6:5-8; 7:1-5, 7, 10, 12, 16b-20, 22-23; 8:2b-3a, 6, 8-12, 13b, 20-22), it flows nicely on its own.

6. Historical referents. Freedman alleges that if you take the traditional views of each source’s composition (for instance, that J was a Judean source), you will see the biases of that source within the text. For instance, Schechem (the capital city of Northern Israel) is spoken of in negative connotations in J’s account.

7. Linguistic classification. Freedman argues that J and E reflect a more ancient stage in Hebrew language development than P and D.

CRITICAL BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP PART 3 – THE DOCUMENTARY HYPOTHESIS APPLIED TO THE BOOK OF AMOS

8. Identifiable relationships among sources. Freedman claims that P seems to be reflecting on a combined J and E source which means they had been put together before P was written.

9. References in other biblical works. Jeremiah alludes to content in the theorized P source which suggests that P was pre-exilic.

10. Marks of editorial work. Freedman theorizes that when a seemingly parenthetical comment is inserted after a sentence and that sentence is then repeated after the parenthetical, that is the mark of a redactor to return to the flow of the preceding story.

Critical Assumptions and Their Counters

Before addressing any of these points explicitly, it is worth assessing what Freedman’s underlying assumptions are. For instance, he seems to be warning scholars to be cautious in their assessment of the truthfulness (or lack thereof) of the text:

“Relatively little of the Torah’s story can be verified historically. Sufficient evidence from extrabiblical sources and archaeological artifacts is lacking to make judgments for or against historical veracity.”

However, a quick scan of his arguments (and a cursory knowledge of common counter responses) demonstrates that the critical perspective is not primarily concerned with being cautious to reach conclusions, but with throwing caution to the wind to read the text through culturally biased assumptions of skepticism. This is different from more conservative approaches to biblical development which are open to the strong possibility of the Jewish community crafting the final forms of certain texts, but not in such a way that contradictory texts are smashed together.

RELATED: CRITICAL BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP PART 4 – THE HISTORICITY OF THE BOOK OF DANIEL

For instance, critical scholars (such as Kuenen) have distinguished E from J on the basis that in J God seems more anthropomorphic and personal whereas in E He is described more often as lofty and distant (Freedman in this article offers a different perspective—that J and E are more anthropomorphic but D isn’t). But why conclude that these are necessarily two distinct sources? In Genesis 1 and 2, for instance, one could argue that we find two different stories from J and P placed side-by-side or one could take the text at face value and see one chapter as describing the mighty God creating the universe and the second detailing how He, the God who is called by a personal name, interacts with humanity on a more personal level.

The fact that Genesis 1 and 2 use different names for God and tell us somewhat different things about God is difficult to argue with and this makes the sacred names division of sources seem quite plausible, though the critical use of such an idea takes some unwarranted leaps.

As for the usefulness of the divine names criterion to distinguish sources in the Torah, Johannes Dahse showed as early as 1903 that the Greek translation of the Torah (the LXX or Septuagint), which translated Yahweh as kyrios and Elohim as theos, switches them up around 180 times. This calls into question whether the Hebrew text we possess today can be used rigidly to assert which divine name was used where. This contradicts Freedman who argues that, “The LXX and Samaritan Pentateuch have minimal differences from the MT in divine names and have been shown by Skinner to confirm these authorial identifications.”

There is some debate in critical scholarship over whether the proposed sources reflect the concerns which they are alleged to. Mowinckel argued that a written J came first and that an oral E, not being a distinct source itself, merely adapted it by making minor alterations. He also denied that E was of northern Israelite origin (a claim which Freedman makes in the article). Volz and Rudolph similarly argued against E as a distinct source but only as an editor of J. Kennett argued that J was actually later than E, though he placed its composition back into the northern kingdom. And this is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to contradictory critical views about the alleged sources. Does this confusion not point to the distinct possibility that critical scholars are merely devising clever but unwarranted schemes which are united primarily in their assumption of the untrustworthiness of the text?

And what of the confirmation bias and circularity built into these hypotheses? Freedman perhaps shows his hand when he argues that P is clearly a distinct source because the other sources don’t discuss the tabernacle. Of course, it is on the basis of P’s discussion of priestly concerns (such as the tabernacle) that critical scholars argue that it is a distinct source in the first place! One could just as easily suggest that only a hypothetical source S discusses sexual purity, isolate the sections that discuss sexual purity, and then use that as “evidence” of an S source.

In conclusion, the Documentary Hypothesis is an assumption of biblical untrustworthiness in want of evidence. At minimum, it does not justify doubting the unified view of scripture but merely presents a possible, but very hypothetical, alternative.

May 2, 2018

PODCAST: Responding to Heretic Happy Hour’s Shots at the Canon

In this episode I respond to claims from the podcast Heretic Happy Hour that the existence of a biblical canon silences God, reflects patriarchal desires to control people, and was the result of a fourth century council to do just these things. I also spend a little time with the issue of books allegedly falsely attributed to Paul in the New Testament. Tune in for an Overjoyed Orthodoxy ‘Our!

Special thanks to Patreon supporters Kelly Smith and Peter Mengel! To learn more about the Cantus Firmus Patreon, check out www.patreon.com/cantusfirmus

Audio:

http://www.cantus-firmus.com/Audio/20180501-RespondingtoHereticHappyHoursShotsattheCanon.mp3

Music:

“The Itis” by Polyrhythmics. Licensed under CC BY 3.0

http://www.needledrop.co/wp/artists/polyrhythmics/

April 30, 2018

A Biblical Worldview of Government Part 3 – How Should Christians Relate to the State?

This is the last article in a series about the biblical view of government and how Christians should relate to it. For more, follow the RELATED tags within the article.

Shifts in Christian Political Involvement in America

In the previous century Christian politics in America went through two major transformations. The first was from a broadly politically progressive faith to a somewhat politically detached one due to the rise of secularism typified in the events of the Scopes monkey trial. The next transformation, from politically uninvolved to politically conservative, originally coalesced around the purported right (under the banner of religious freedom) of Christian colleges like Bob Jones University to discriminate against students of color while receiving federal funds. This right-wing Christianity was finally consolidated by bringing evangelicals over to the pro-life movement (a movement from which we had been conspicuously absent when the decision of Roe v Wade came down in 1973) and was further fortified over issues such as prayer in school, gays in the military, and gay marriage.

RELATED: A BIBLICAL WORLDVIEW OF GOVERNMENT PART 1 – THE ORIGIN AND ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

RELATED: A BIBLICAL WORLDVIEW OF GOVERNMENT PART 2 – LEFT VERSUS RIGHT

Such rapid shifts on public policy might suggest that scripture doesn’t give us anything to stand on when it comes to how we ought to view the state and relate to it. However, there are some railings we can place around the issue of political involvement to help us to navigate this rough terrain more biblically.

Christians and State Violence

To begin with, the New Testament is fairly explicit that, even though God may use the violence of the state for good ends, Christians cannot participate in that violence. Though the apostle Paul is clear that Christians may not “repay anyone evil for evil,” or “take revenge . . . but leave room for God’s wrath” (Romans 12:17-19, NIV), he is also clear that the magistrates (which, in Paul’s time, were uniformly pagan polytheists) are “God’s servants, agents of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer” (Romans 13:4, NIV).

Jesus also excludes Christians from performing the violent activities of the state when He explains to Pilate why, though He is a king, His servants won’t fight to release Him from the death penalty imposed upon Him by the state oppressors:

“My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jewish leaders. But now my kingdom is from another place” (John 18:36, NIV).

Indeed, Christians are to “turn the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39) and remember that:

“Christ suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps. ‘He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth.’ When they hurled their insults at him, he did not retaliate; when he suffered, he made no threats. Instead, he entrusted himself to him who judges justly” (1 Peter 2:21-23, NIV).

RELATED: PODCAST: MAKE CHRISTIANITY WEAK AGAIN

The reason for this non-violence on the part of Christians is simple:

“our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Ephesians 6:12, ESV). The chief influence of Christians upon society ought to be to transform hearts and minds, not to coerce bodies. Our goal should not be to make America great again, but to make Christianity weak again—at least when it comes to our ability to coerce others through physical force. Indeed, we are to be weak as Christ was “weak” in the face of political violence and power. In fact, Paul is even clear that it is not our job to judge those outside of the church, but that we must leave that work to God (1 Corinthians 5:12).

Can a Christian Be Involved in Politics?

If the state’s tool is destructive violence, and Christians are forbidden its exercise, how then should the two relate? A traditional Anabaptist answer to this question is to forbid Christians from participation in the state in any capacity, though the New Testament isn’t as explicit on this point as we would like it to be—its human authors did not seem to foresee a time when Christians would have the opportunity to participate in any meaningful way in statecraft. But if we are to venture out into the world of politics, we must remember the lessons listed above which scripture seeks to teach us:

1. The kingdom of God and the kingdom of men are distinct.

2. The kingdom of God is not, at this stage, physical, so it does not use violence but spiritual power.

RELATED: HOW SHALL WE THEN VOTE?

If then, we are to participate in the state, we must do so as those who cannot ultimately give ourselves only to secular realities. What then should we encourage the state to do from our unique vantage points as Christians?

The apostles Peter and Paul give us some direction for the kind of state that we as Christians should prefer. For one, we should prefer a state which benefits those doing good and is a terror to those doing evil (Romans 13,1 Pet 2:14), not the reverse. In other words, we should prefer a state where justice is done and the corrupt are not rewarded. In addition, we ought to prefer a state which gives us the freedom to preach the gospel and live out our lives unmolested (1 Timothy 2:1-3). We also ought to be willing to use our influence to rally for the cause of peace, knowing that this is at the heart of God and that war destroys precious instances of the image of God. Let us seek to apply the theological insights of the 2nd century church father Justin Martyr, who wrote in his First Apology that God’s promise that future nations would beat their swords into ploughshares had been fulfilled in the church, whose members, “formerly used to murder one another [though] do not only now refrain from making war upon our enemies, but also, that we may not lie nor deceive our examiners, willingly die confessing Christ.”

This command to peace must be followed by the disciples of Christ, but we should also use our influence for the cause of peace in this age. This is to say that we should seek to make the secular world look a little bit like the kingdom of God through our example of peacemaking.

This seems to point us in the direction of libertarianism—looking to focus the state upon the essential tasks of protecting the safety of its people, deterring those who would seek to harm others, and allowing the free and open preaching and living out of the gospel of Christ. It should be stated with firmness that this requires cultivating an environment where the freedoms of religion, speech, and assembly can flourish for everyone, lest we give the state the power to regulate our own freedom of worship after we have sought to use its violence to regulate that of others. This is important not only for our freedom as Christians, but also for the purpose of our evangelism—we cannot preach a gospel of love to a people whom we have sought to subject politically. We cannot tell people about the freedom of Christ after we have done the Christian equivalent of forcing them to pay the jizya.

Going back to the issue of gay marriage which was discussed earlier in regard to left and right wing dichotomies, something of a biblical answer to this issues begins to emerge. If we do not desire a state which has the power to regulate our marriages or censure those who hold what society sees as the wrong view of marriage, we should seek a state which does not side with either a right wing evangelical or a gay activist solution to the issue, but one which allows non-celibate gay people and Christians to co-exist peacefully.

To summarize, an ideal society for Christians to live in will be broadly libertarian for at least five reasons:

1. Christians can live without fear of oppression.

2. The gospel can be shared openly.

3. The faith cannot be as easily compromised by political power nor can one powerful group of Christians enforce a false orthodoxy on others.

4. Evangelism will not be thwarted by our attempts to subjugate others.

5. The Christian goal of peacemaking can be more easily realized in a society which has as its default position a desire to avoid war.

RELATED: PODCAST: CANTUS FIRMUS AT THE MOVIES EP. 4 – THE MISSION (W/ KEITH GILES)

In this sense, the classical liberal theory of the rights of man is somewhat confirmed by a rational application of the principles of scripture. However, a Christian should not see humanity through the Enlightenment lens of humans having natural rights which give us the power to do whatever we choose to whomever we want–a right which we give up by participation in a “social contract.”

A Christian should instead see human rights through the lens of scripture which tells us that all human beings are made in the image of God and that the value of each and every human must be respected by all—even non-Christian kings. Our rights are not based on our animal nature, but upon the divine image represented in our humanity. Building on that foundation, we should also note that the Hebrew mind didn’t think in terms of individual rights, but of relational obligations. A Christian should want to think in libertarian terms not because of an Enlightenment philosophy of rights, but because Christ has commanded us to do unto others as we would have them do unto us. This distinction between Christianity and Enlightenment era liberalism is an important one because it allows us to discern whether, if liberty cannot make a way to providing an essential service to those in need, the state may be called upon to do so lest our brothers and sisters in humanity perish.

Conclusion

The lens through which the Christian ought to view the world should be Christ—particularly His chosen weakness in order that He might love and serve others (Phillipans 2:6-9). This requires that we give up our desires to subjugate other human beings and to treat the political arena as a battleground by which we wage crusades using the pagan tools of kings and soldiers. Indeed, we should go out of our way to love others and ensure their peace and liberty. If we are to call everyone to the marriage supper of the lamb, we must make room at the earthly table where we presently dine and stop stockpiling all of the food for ourselves.