Jamie Parsley's Blog, page 19

November 6, 2022

All Saints Sunday

November 6, 2022

+ This past Tuesday was a very important day in the Church.

Capital C.

The wider, universal Church.

It was one of the really important feast days.

November 1 was All Saints Day.

It is the day in which we commemorate all the saints who now dwell with God in heaven.

It is a beautiful feast.

And we, here at St. Stephen’s, celebrated the eve of that day appropriately.

We celebrated the Eve of All Saints Day on Monday by celebrating a new saint—our own dear Holly Holden-Eklund.

We celebrated her life with a Burial Office that afternoon.

And on Wednesday, the Feast of All Souls, we celebrated our Annual Requiem Mass in which we remembered all of our departed loved ones, and afterward, we buried Holly’s ashes in our memorial garden.

And it was beautiful and sad and bittersweet all at once.

We Episcopalians do these things well.

We do funerals well, we do commemorating our deceased loved ones well.

We celebrate the saints—those who are both well-known saints and those saints who might only be known to a few—very well as Episcopalians.

And when anyone from St. Stephen’s dies, or when anyone close to someone at St. Stephen’s dies, you will always receive an email with a request for prayer.

And the request for prayer will usually begin with these words:

“The prayers of St. Stephen’s are requested for the repose of the soul of …so-and-so.”

Occasionally, someone will ask me about that prayer request.

Someone will ask,

Why do we pray for the dead?

We do we pray for the repose of their souls?

After all, they’ve lived their lives in this world and wherever they’re going, they’re there long before a prayer request goes out.

The fact is, we DO pray for our dead.

We always have—as Anglicans and as Episcopalians.

You will hear us as Episcopalians make the petition for prayer when someone dies that you won’t hear in the Lutheran Church, or the Methodist Church or the Presbyterian Church.

Praying in such a way for people who have passed has always been a part of our Anglican tradition, and will continue to be a part of our tradition.

And I can tell you, I like that idea of praying for those who have died.

But, I want to stress, that although we and Roman Catholics both pray for our dead, we don’t pray for people have died for the same reasons Roman Catholics do.

In other words, we don’t pray to free them from purgatory, as though our prayers could somehow change God’s mind.

Rather, we pray for our deceased loved ones in the same way we pray for our living loved ones.

We pray for them to connect, through God, with them.

We pray to remember them and to wish them peace.

Still, that might not be good enough answer for some (and that’s all right).

So…let’s hear what the Book of Common Prayer says about it.

And, yes, the Book of Common Prayer does address this very issue directly.

I am going to have you pick up your Prayer Books and look in the back, to the Catechism.

There, on page 862 you get the very important question:

Why do we pray for the dead?

The answer (and it’s very good answer): “We pray for them, because we still hold them in our love, and because we trust that in God's presence those who have chosen to serve [God] will grow in [God’s] love, until they see [God] as [God] is.”

That is a great answer!

We pray that those who have chosen to serve God will grow in God’s love.

So, essentially, just because we die, it does not seem to mean that we stop growing in God’s love and presence.

I think that is wonderful and beautiful.

And certainly worthy of our prayers.

But even more so than this definition, I think that, because we are uncertain of exactly what happens to us when we die, there is nothing wrong with praying for those who have crossed into that mystery we call “the nearer Presence of God.”

After all, they are still our family and friends.

They are still part of who we are.

Now, I know that this idea of praying for those who have died makes some of us very uncomfortable.

And I understand why.

I understand that it flies in the face of some of our more Protestant upbringings.

This is exactly what the other Reformers rebelled against and “freed” us from.

But, even they never did away with this wonderful All Saints Feast we are celebrating this morning.

This morning we are commemorating and remembering those people in our lives who have helped us, in various way, to know God.

As you probably have guessed from the week-long commemoration we have made here at St. Stephen’s regarding the Feast of All Saints, I really do love this feast.

With the death of many of my own loved ones in these last few years, this Feast has taken on particular significance for me.

What this feast shows me is what you have heard me preach in many funeral sermons again and again.

I truly, without a doubt, believe that what separates those of us who are alive here on earth, from those who are now in the “nearer presence of God” is truly a very thin one.

And to commemorate them and to remember them is a good thing for all us.

Now, I do understand, as I said before, that all this talk of saints makes some of us who are more “Protestant minded” a bit uncomfortable.

But…I do want us to think long and hard about the saints we have known in our lives.

And we have all known saints in our lives.

We have known those people who have shown us, by their example, by their goodness, that God works through us.

And I want us to at least realize that God still works through us even after we have departed from this mortal coil.

Ministry in one form or the other, can continue, even following our deaths.

Hopefully, we can still, even after our deaths, do good and work toward furthering the Kingdom of God by the example we have left behind.

For me, the saints—those people who have gone before us—aren’t gone.

They haven’t just disappeared.

They haven’t just floated away and dissipated like clouds out of our midst.

No, rather they are here with us, still.

In these last few years, after losing so many people in my family and among close friends, I think I have felt their presence most keenly many times, but often times most keenly, at times, here at this altar when we are gathered together for the Eucharist then at any other time.

I have felt them here with us.

And in those moments when I have, I know in ways I never have before, how thin that veil is between us and “them.”

You can see why I love this feast.

It not only gives us consolation in this moment, separated as we are from our loved ones, but it also gives us hope.

We know, in moments like this, where we are headed.

We know what awaits us.

No, we don’t know it in detail.

We’re not saying there are streets paved in gold or puffy white clouds with chubby little baby angels floating around.

We don’t have a clear vision of that place.

But we do sense it.

We do feel it.

We know it’s there, just beyond our vision, just out of reach and out of focus.

And “they” are all there, waiting for us.

They—all the angels, all the saints, all our departed loved ones.

So, this morning—and always—we should rejoice in this fellowship we have with them.

We should rejoice as the saints we are and we should rejoice with the saints that have gone before us.

In our collect this morning, we prayed that “we may come to those ineffably joys that you have prepared for those who truly love you.”

Those ineffably joys await us.

They are there, just on the other side of that thin veil.

We too will live with them in that place of unimaginable joy and light.

And that is a reason to rejoice this morning.

October 31, 2022

The Memorial Service for Holly Holden-Eklund

October 31, 2022

St. Stephen’s, Episcopal Church

Fargo, ND

+ I have to say: I feel strange today.

It feels strange to gather here today on this beautiful Halloween afternoon to say goodbye to Holly.

Although she’s been gone for almost 2 months, there are moments when I think maybe she’s not gone.

I still expect to see her post something on Facebook, or like a post or to comment on something I post.

The world without Holly is a strange world.

It seems just a bit more…empty.

It seems a bit less wonderful.

But as strange as it to be saying goodbye to Holly, I am grateful today.

I am grateful for Holly and for her presence in my life.

And let me tell you: it was a presence.

And I think most of who knew her and loved her feel the same today.

Her presence in our lives was a big thing.

She was a true presence.

A strong presence.

And I am grateful for that presence n my life.

I am also grateful that I was able to be her priest.

And her friend.

It doesn’t seem all that long ago when Michael first started attending our Wednesday night Mass here at St., Stephen’s.

He attended several times before Holly attended.

When she came here for the first time, she was cautious to say the least.

This Irish woman from Worchester, Massachusetts who was raised Roman Catholic, but who put that behind her many years before, came here a bit wary about this unique little church with its well, unique priest.

I remember the first time she attended was around the feast of the Purification in early February because I remember she brought candles to get blessed.

She then began attending almost every Wednesday with Michael.

However, she wasn’t quite able to bring herself to come forward for Holy Communion.

Despite our regular invitation that all people here are welcome to receive Communion, she just couldn’t do it.

All that residual Catholic baggage just prevented her from coming forward.

But I remember so well that Wednesday night when finally she came up, knelt here at this altar rail.

She beamed up at me as I gave her Communion.

It was a special moment.

It was a holy moment.

And it is one I find myself cherishing to this day.

Over the years, St. Stephen’s became an important place for Holly.

It became her spiritual home.

And she was loved deeply here.

Our Wednesday nights usually consisted of 6:00 Mass followed by supper at a local restaurant.

I think over the years, we ate at every restaurant in Fargo and Moorhead, some good, and some…well…not so good.

And I think we experienced every kind of server one could ever experience.

God help the poor unfortunate server who just happened to call Holly “Ma'am.”

But over those Masses and over those meals, we all bonded with each other.

And Holly and Michael became important and vital members of our parish.

I know these last years were hard on her.

As her health failed, as the pandemic hit, as she shuffled from hospitals to nursing facilities, she really struggled at times.

Of course, Michael was there to help her along the way.

But through it all, she remained fiercely strong and fiercely defiant.

Even over the last few days before she finally left, I was amazed at her strength.

And when she was gone, all of us who knew her felt it deeply.

I think it’s very appropriate that we are gathered here today, on Halloween.

Michael chose this day deliberately.

This evening of course is the Eve of the Feast of All Saints—a very important feast day for the Church.

But it is also a very important pagan holiday.

And for all of us it is a time in which the veil between this world and the next gets very thin.

It is a time in which we realize that right there, just on the other side of that thing veil, they are all there—all those who have gone on.

And at this time of the year, they draw close to us.

If we are spiritually aware, if we hone our spiritual senses enough, we can feel them, right here, with us.

Today we feel Holly right here with us.

And she is whole, and she is healthy, and she is beautiful and she is fully alive.

For Holly, her pains are behind her.

For Holly, she has finished with sad time.

She will never again shed another tear.

God has wiped away every tear from Holly’s eyes.

She will never cry another tear.

We…well, we are not so lucky.

At least right now.

We have not yet emerged from our great ordeal.

We will shed many tears for Holly Holden-Eklund.

But we know that, one day, our tears will be wiped away for good.

These tears we cry today will be wiped away.

One day that veil will be lifted for us, and we will move over to that other side, and we will be greeted by Holly and all those who are there waiting for us.

And it will be a great day.

All this reminds us that our goodbye today is only a temporary goodbye.

All that we knew and loved about Holly is not gone.

It is not ashes.

It is not lost forever from us.

All we loved, all that was good and strong and defiant and rebellious and gracious and beautiful in Holly—all that was fierce and amazing in her—all of that dwells now in a place of light and beauty and life unending.

And we will see that smiling face again.

We will see her again.

And it will be beautiful.

For now however, we need to celebrate her.

We need to remember her.

We need to commemorate and give thanks for all that she was to us.

To the end, Holly proved to be strong and independent.

To the end, she remained a strong, Irish woman.

She showed us all true courage, true strength, true determination.

She showed us what real courage was.

And we should be grateful for that.

The fact is, we will all miss her.

But I can tell you we will not forget her.

Holly Holden-Eklund is not someone who will be easily forgotten.

She is not someone who passes quietly into the mists.

Her fierce determination lives on in us.

Her strength, her dignity lives with Michael, and with her grandsons, and with her many friends, and with her priest.

At the end of this service, we will all stand and I will lead us in something called the Commendation.

The commendation is an incredible piece of liturgy.

As a poet, Holly would agree that it’s an incredible piece of poetry.

But it’s more than poetry.

In those words, we will say, those very powerful words:

All of us go down

to the dust; yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia,

alleluia, alleluia.

That alleluia in the face of death is a defiant alleluia.

It is fist shaken not at God, but it is a fist shaken at death.

It is the fist Holly shook at death.

Not even you, death, not even you will defeat me, Holly seems to say.

I will not fear you.

And I will not let you win.

And, let me tell you, death has not defeated Holly Holden-Eklund.

Even at the grave, she makes her song—and we with her:

Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.

It is a defiant alleluia we make today with her.

So let us be defiant.

Let us shake our fists at death today.

Let us say our Alleluia today in the same way Holly would.

Let us face this day and the days to come with gratitude for this incredible person God let us know.

Let us be grateful.

Let us be sad, yes.

But let’s remind ourselves: death has not defeated her.

Or us.

Let us be defiant to death.

Let us sing loudly.

Let us live boldly.

Let us stand up defiantly.

That is what Holly would want us to do today, and in the future.

Into paradise may the angels lead you, Holly.

At your coming may the martyrs receive you.

And may they bring you with joy and gladness into the holy city Jerusalem.

Amen.

October 30, 2022

21 Pentecost

October 30, 2022

Luke 19.1-10

+ When I was a little boy at the Lutheran Church at which I grew up, we used to sing a little song in Sunday School.

I haven’t heard since then.

I bet James knows the song.

But it went like this:

Zacchaeus was a wee little man,

A wee little man was he.

He climbed up in the sycamore tree,

The Savior for to see.

In fact, I even remember an illustration of Zacchaus for us little kids.

It showed this little man in a tree looking at Jesus.

It must’ve been the fact that he was “wee little man” that made him so appealing to kids.

At the time, I was certain that Zacchaeus was a munchkin of some sort.

But his wee stature makes our Gospel reading a seemingly pleasant story.

We’ve all heard this story of how Zacchaeus climbed the Sycamore tree to see Jesus.

And on the surface, it really is a pleasant story.

It seems to be a story of faith and persistence and how, with faith and persistence, Zacchaeus invited Jesus to his home, which Jesus did and ate with him.

A very nice story.

But…(there’s always a “but”) to trulyunderstand this story we have to, as we always should, put it within the proper context of its time and its culture.

When we do that, we find layers to this story that we might not have seen at first glance.

The first clue that something more is going on in this story is the fact that Zacchaeus is identified as a chief tax collector.

And that he is rich.

The fact that he is rich is actually a bit redundant.

The chief tax collector is, of course, going to be rich.

But it isn’t that he’s rich that we might find something deeper going on.

The really big deal to this story is that he is a tax collector.

That’s important.

The reason Jesus uses tax collectors in this way is important.

It’s important because a tax collector at that time, in that culture, was one of the worst people one could imagine, if you were a good Jew, that is.

On one hand, he was seen as a traitor.

He had sided with the occupying government—the Roman government—and collected taxes from his own people to pay the Roman government.

These tax collectors were also notorious for lining their own pockets.

And this might be why there is mention of the fact that he is rich.

He, no doubt, was rich because he stole money from the people.

It was easy for tax collectors to skim the coffers so they could keep what they wanted for themselves.

And even if they didn’t resort to such underhanded dealings, they were usually judged by the general population as doing so.

Certainly, no one trusted and certainly no one liked tax collectors.

But this wasn’t the end of Zacchaeus’ troubles.

Probably worst of all, Zacchaeus was seen as ritually unclean by his fellow Jews.

After all, he handled the money of the Romans, which had on it, an image of the Emperor.

Since the Emperor was viewed as divine, as a god, what Zacchaeus was handling then was essentially a pagan image and to handle it was to make one’s self unclean according to the Jewish Law.

So, Zacchaeus—poor Zacchaeus—was in a lose-lose situation.

He was despised as being both a traitor and as being religiously unclean.

And Jesus knew full well who Zacchaeus was and what he stood for in his world when he called up to Zacchaeus in that tree and said, “Zacchaeus, hurry and come down; for I must stay at your house today.”

Jesus knew full well that Zacchaeus was unclean—nationally and religiously.

Zacchaeus was an outcast.

He was living on the fringes of his society.

He probably had few friends—and the few friends he had were no doubt friends with ulterior motives—friends who knew they could get something out of Zacchaeus.

When we re-examine our Gospel story again knowing what we know now, the story takes on a very different tone.

It becomes less of a sweet, Sunday School story about a short man and becomes quite a radical story.

It shows us that Jesus truly was able to step outside the boundaries of his day and reach out to those who truly needed him.

Now, for Zacchaeus, he does the right thing.

He says to Jesus that he will not only pay back half of his possessions, but he even offers to pay back four times the amount he stole.

This is really incredible because Jewish Law didn’t expect anything close to four times the amount being paid back.

In the 6th Chapter of Leviticus, whenever anyone commits a trespass against God by deceiving a neighbor in the matter of a deposit or pledge or by robbery or if one has defrauded a neighbor, the one who defrauded shall pay back the principal and add one-fifth to it. (Leviticus 6.1-7)

But we know why Zacchaeus makes the offer he does.

For those of us who are truly repentant, that’s what it feels like sometimes, doesn’t it?

I often hear from people about how sorry they are for this and for that.

But on those occasions, when I am truly sorry—truly repentant, truly striving to make right the wrongs I’ve done—I find myself wanting to go above and beyond the call of duty.

I want to make right the wrongs I’ve done and feel as though it is truly right again.

That is what Zacchaeus is truly saying to Jesus.

And that is what we should be truly saying to God as well when we turn away from the wrongs we’ve done and attempt to do right again.

The story of Zacchaeus shows us that sometimes Jesus must violate some social norms and even the popular interpretation of scripture.

Just by going to Zacchaeus’ home, Jesus has made several major faux pas.

He has talked with an unclean person.

He has gone with this unclean person to the house of the unclean person—a household which according to Jewish Law is unclean as well.

That means the building, the wife, the children, anyone who enters it, is unclean.

So Jesus enters the unclean dwelling of an unclean person.

And what does he do there?

He goes there and he probably eatsthere.

Again, yet another thing the Law was clear was wrong.

Eating food prepared and served by unclean people made one unclean as well.

And yet, as we know, Jesus was not made unclean by any of this.

What in fact happens?

Something amazing.

Jesus goes and shows them that this man is not unclean anymore because God has forgiven him.

Jesus goes and shows that this man, his family, his house, his food—his life is no longer unclean.

God has forgiven him.

Jesus’ actions speak louder than words here.

Jesus’ actions shows that God’s forgiveness was bigger than anything anyone at that time could possibly understand.

And even for us—now.

God’s forgiveness turns the uncleanliness of that place into a place of redemption and joy.

And that is how this story for today really ends.

It’s never mentioned outside of the fact that Zacchaeus is “happy to welcome” Jesus, but there seems to be an almost palpable joy present in this story.

The word Joy is never even used.

But we know—we feel—that as this story ends, there is a true and wonderful joy now living in that house of Zacchaeus because of he has been redeemed.

The lost have been saved.

The unclean have been cleansed.

The wrongs have been righted.

God’s love has broken through.

See, this is what want for our story as well.

No matter what we’ve done, no matter how unclean we or the standards of our own day or society, the forgiveness and love of God in our lives redeems us.

With God’s love and forgiveness, we have been found.

With God’s love and forgiveness, joy has replaced whatever dark emotions lived within us at one time.

Those of who have climbed the sycamore tree searching for something, who have gone here and there searching for something among the crowds, have not found salvation in those places.

Where have we found this forgiveness of God? Right here. In our own homes—in our own place.

God’s forgiveness and love comes to us in a familiar place and we are better for it.

God’s love and forgiveness comes and fills our familiar places with joy.

Jesus is still saying to each of us today, “hurry and come down, for I must stay at your house today.”

He says that because he knows that God has forgiven the sins of Zacchaeus and has freed him from his uncleanliness.

And Jesus knows this in our lives as well.

Our house is this life that we have.

It is this house God’s love enters and dwells within.

And by God’s love, by God’s forgiveness, we are purified.

And realizing that fills us with a truly palpable joy!

And when we leave here and go into the world, we do so knowing God has redeemed us and made us whole so that we can share that joy we feel with others.

And most importantly, as people cleansed, as people truly loved by a loving God, we no longer see the uncleanness of others.

We only see other people truly loved and truly forgiven by a loving God.

So, let us listen to Jesus’ words to us.

“Today salvation has come to this house.”

That salvation of God is with us.

Here.

Now.

Let us rejoice in that salvation.

And let that implied joy we find in our Gospel story come bubbling up within us at this news so that we can go out and make the world a better place by our joy.

Let us pray.

Holy and loving God, fill us with the joy at knowing that your love and forgiveness has entered into our homes and that you dwell here with us. Let us live this holy joy in our lives so that we can share this joy with others. In Jesus’ name we pray. Amen.

October 23, 2022

20 Pentecost

October 23, 2022

Luke 18.9-14

+ Since I’ve been your priest here at St., Stephen’s of quite some time now, you have gotten to known some of my pet peeves.

Let’s open it up.

What are some of my pet peeves?

Well, certainly only one of the big ones as a priest is none other than: triangulation.

If you want to set me off like a rocket, try to nudge me into that fun catch-22.

Here’s essentially what triangulation is:

Sometimes people come to me as a priest and, because they have some issue with another parishioner, they want me to go to that other person and deal with the situation this other person is having on their behalf.

The excuse here is that, since it is a church issue, the “church guy” should take care of this issue for them.

After all, I must be on their side of this issue, right?

Now, to be clear, THEY don’t want to confront the person.

But they seem to think it’s somehow the priest’s job to confront that person for them and for this particular issue that they themselves see as something that needs to be confronted.

Now, before we go on from here I just want to be clear:

It is NOT the priest’s job to do this.

Nowhere in my contract does it say I am to do this kind of a job.

What this triangulation does is it puts the priest not in their rightful position as priest, but only puts them in an awkward situation in which they can’t win.

Stuck right in the middle.

To be clear, it is not the priest’s job to be THAT PERSON.

Triangulation, as you can guess, is one of the quickest “clergy killers” out there.

You want your priest out, all of you have to do is try to draw them into an ugly triangle like this.

Actually, I luckily, have not really had to deal with triangulation much here at St. Stephen’s very often.

And those times when it has come up, I have reacted pretty strongly against it.

One of the great aspects of St. Stephen’s has been the self-reliance of the parishioners.

But, in other congregations I’ve served, let me tell you, they do attempt to resort to triangulation quite often.

And…I hear many fellow clergy share stories in which they have found themselves trapped in the middle of those situations.

In the past, when I have found myself being nudged into such a situation, I finally have had to ask a question.

I, of course, tell the person: you need to talk to this person if you have an issue with them.

You’re talking to them will probably be much more successful than my talking to them on your behalf.

But, if that doesn’t work—and it usually doesn’t work—I ask those people: “have you tried praying for them?”

And I’m not saying, praying for them to change, for them to be more like what you expect them to be.

Have you just prayed for them, as they are?

Because when we do that, we find that maybe nothing in that other person changes—ultimately we can’t control how other people act or do things—but rather we are the ones who change.

We are the ones who find ourselves changing our attitude about that person, or seeing that person from another perspective.

However it works, prayer like this can be disconcerting and frightening.

Let me tell you.

I have done it.

I’ll be honest: I have had issues with people who do not meet my own personal expectations.

But I do find that as I pray for them, as I struggle before God about them, sometimes nothing in that other person changes.

(God also does not allow God’s self to be triangulated)

But I often find myself changing my attitude about them, even when I don’t want to.

Prayer, often, is the key.

But not controlling prayer.

Rather, prayer that allows us to surrender to God’s will.

That’s essentially what’s happening in today’s Gospel reading.

In our storyw e find the Pharisee.

A Pharisee was a very righteous person.

They belonged to an ultra-orthodox sect of Judaism that placed utmost importance on a strict observance of the Law of Moses—the Torah.

The Pharisee is not praying for any change in himself.

He arrogantly brags to God about how wonderful and great he is in comparison to others.

The tax collector—someone who was ritually unclean according the Law of Moses— however, prays that wonderful, pure prayer

“God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

It’s not eloquent.

It’s not fancy.

But it’s honest.

And it cuts right to heart of it all.

To me, in my humble opinion, that is the most perfect prayer any of us can pray.

“God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

It’s a prayer I have held very, very dear for so long.

And it is a prayer that had never let me down once.

Prayers for mercy are probably one of the purest and most honest prayers we can make.

And what I love even more about this parable is the fact that the prayer of the Pharisee isn’t even necessarily a bad prayer in and of itself.

I mean, there’s an honesty in it as well.

The Pharisee is the religious one, after all.

He is the one who is doing right according to organized religion.

He is doing what Pharisees do; he is doing the “right” thing; he is filling his prayer with thanksgiving to God.

In fact, every morning, the Pharisee, like all orthodox Jewish men even to this day, pray a series of “morning blessings.”

These morning blessings include petitions like

“Blessed are you, Lord God, King of the Universe, who made me a son of Israel.”

“Blessed are you, Lord God, King of the Universe, who did not make me a slave.”

And this petition:

“Blessed are you, Lord God, King of the Universe, who did not make me a woman.”

So, this prayer we hear the Pharisee pray in our story this morning is very much in line with the prayers he would’ve prayed each morning.

Again, we should be clear: we should all thank God for all the good things God grants us.

The problem arises in the fact that the prayer is so horribly self-righteous and self-indulgent that it manages to cancel out the rightness of the prayer.

The arrogance of the prayer essentially renders it null and void.

The tax collector’s prayer however is so pure.

It is simple and straight-to-the-point.

This is the kind of prayer Jesus again and again holds up as an ideal form of prayer.

But what gives it its punch is that is a prayer of absolute humility.

And humility is the key here.

It gives the prayer just that extra touch.

There is no doubt in our minds as we hear this parable that God hears—and grants—this prayer, even though it is being prayed by someone considered to be the exact opposite of the Pharisee.

Whereas the Pharisee is the religious one, the righteous one, the tax collector, handling all that pagan unclean money of the conquerors, is unclean.

He is an outcast.

Humility really is the key.

And it is one of the things, speaking only for myself here, that I am sometimes lacking in my own spiritual life.

But, humility is important.

It is essential to us as followers of Jesus.

St. Teresa of Avila, the great Carmelite saint, once said, “Humility, humility. In this way we let our Lord conquer, so that [God] hears our prayer.”

I think we’re all a bit guilty of lacking humility in our own lives, certainly in our spiritual lives and in being self-righteous when it comes to sin.

We all occasionally find ourselves wishing we could control and correct the shortcomings and failures of others.

Oh, let me tell you!

When a person fails miserably, or is caught in a scandal, I find myself saying: “Thank God it’s them and not me.”

Which is terrible of me!

And maybe that’s also an honest prayer to make.

Because what we also say in that prayer is that we, too, are capable of being just that guilty.

We all have a shadow side.

And maybe that’s what we’re seeing in those people we want to correct.

There’s no way around the fact that we do have shadow sides.

But the fact is, the only sins we’re responsible for ultimately—the only people who can ultimately control—are our own sins—not the sins of others.

We can’t pay the price of other’s sins nor should we delight in the failings or shortcomings of others.

All we can do as Christians, sometimes, is humble ourselves.

Again and again.

Sometimes all we can do is let God deal with a situation, or a person who drives us crazy.

God, have mercy on me, a sinner

We must learn to overlook what others are doing sometimes.

Doing so, exhausts me.

And so I don’t know why I would want to deal with other’s issues if my own issues exhaust me.

There are too many self-righteous Christians in the world.

We know them.

They frustrate us.

And they irritate us.

We don’t need anymore.

What we need are more humble, contrite Christians.

We need to be Christians who don’t see anyone as inferior to us—as charity cases to whom we can share our wealth and privileges and whom we wish to control and make just like us.

That is true humility.

In our own eyes, if we carry true humility within us, if we are our own stiffest and most objective judges, then we know that we are the most wretched of them all and that we are in no place to condemn others.

In dealing with others, we have no other options than just simply to love those people—fully and completely, even when they drive us crazy.

Sin or no sin, we must simply love them and hate our own sins.

That is what it means to be a true follower of Jesus.

It is essential if we are going to truly love those we are called by Jesus to love and it is essential to our sense of honesty before God.

So, let us steer clear of such self-righteousness.

But, in being humble, let us also not beat ourselves up and be self-deprecating.

Rather, let us work to overcome our own shortcomings and rise above them.

Let us look at others with pure eyes—with eyes of love.

Let us not see the shortcomings and failures of others, but let us see the light and love of God permeating through them, no matter who they are.

And with this perception, let us realize that all of us who have been humbled will be lifted up by God.

All of us will be exalted in ways so wonderful we cannot even begin to fathom them in this moment.

October 16, 2022

19 Pentecost

October 16, 2022

Genesis 32.22-31; 2 Timothy 3.14-4.5; Luke 18.1-8

+ In our reading from the Hebrew scriptures today, we get this very famous, very visual story of Jacob wrestling with the angel.

It is a story that really grabs us.

It captures our imagination.

We can actually picture this momentous event.

Maybe we do because most of us think instantly when we hear this story fo that famous Gustav Dore illustration, of Jacob and the Angel locked in battle, pushing against each other, the angel’s wings raised above the scene.

And I know, we often like to personalize this story.

I know we tend to look at this battle between Jacob (or ourselves) and God.

But I once heard a preacher share how in her opinion this could very much be an analogy for our own struggles with the Word of God or scripture.

I love that analogy.

Because, that also is true.

Oftentimes, our struggle with scripture feels like we’re wrestling with an angel.

You’ve heard me reference scripture as a potentially dangerous two-edged sword.

An often unwieldy two-edged sword, especially for those who use it as a weapon.

And we’ve all known those people who use the Bible as a weapon.

You’ve heard me say, again and again, that if our intention is to cut people down with the sword of scripture, just be prepared…

It too will in turn cut the one wielding the sword.

And I believe that.

That is what scripture does when we misuse it.

However, if we use scripture as it meant to be used—as an object of love, as a way in which God can speak to us—then it is also two-edged.

If we use it as way to open the channels of God’s love to others, then the channels of God’s love will be opened to us as well.

Now, I am very firm on this point.

When it comes to people using scripture in a negative way, wildly waving that sword around, I love crack the knuckles.

Because, I truly do love the Bible.

We all should crack our knuckles whenever we see or hear people misusing the scriptures in such a way.

After all, we are followers of Jesus, and as followers of Jesus we hold the scriptures in the same esteem as Jesus did.

OK. “Esteem” isn’t the right word.

We, as followers of Jesus are steeped and saturated with scripture just as Jesus was seeped and saturated with scripture.

Why?

Well, let’s just take a book in our Prayer Book.

If we look in our Prayer Book, as we do on a very regular basis, back in that place I like to direct us to go sometimes—the Catechism—we find a little expansion on this thinking.

On page 853, you will find this question:

“Why do we call the Holy Scriptures the Word of God?”

The answer:

“We call the Holy Scriptures the Word of God because God inspired their human authors and because God still speaks through the Bible.”

I think that is a wonderfully down-to-earth, practical and rational explanation.

Still, that doesn’t mean that we can use and misuse it by taking it out of context.

And let’s face it; there are scriptures that we don’t like hearing.

But none of gets to edit the Bible.

We don’t get to cross out those things we don’t like.

We have to confront those difficult and uncomfortable scriptures and meet them face-on.

And we have to wrestle with them, as Jacob wrestled with that angel, and in wrestling with them we must use a good dose of reason, and a good dose of tradition, as good catholic-minded Anglicans do.

And if we do that, we come away from those difficult scriptures with a new sense of what they say to us.

For example, I personally might not like what the Apostle Paul says sometimes—I might not even agree with it—but, good or bad, it isn’t up to me.

Or any of one of us.

It’s up to the Church, of which we, as individuals, are one part and parcel.

For us Episcopalians, we don’t have to despair over those things Paul says that might offend our delicate 21st century ears.

We just need to remind ourselves that our beliefs about Scripture are based on a rational approach tempered with the tradition of the Church.

In fact, if we continue reading on page 853 in the Catechism, we will find this answer to the question, “How do we understand the meaning of the Bible?”

The answer:

“We understand the meaning of the Bible by the help of the Holy Spirit, who guides the Church in the true interpretation of Scripture.”

There you see a very solid approach to understanding Scripture.

Reason (in this sense the inspiration of the Holy Spirit), along with the Church (or Tradition) helps us in interpreting Scripture.

Very Anglican.

Think of Richard Hooker’s 3-legged stool of Scripture, tradition and reason.

Such thinking prevents us from falling into that awful muck of fundamentalist heresy.

Such thinking steers us clear of this misconception that that the Scriptures are without flaw.

Such thinking also steers clear of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, with regard to Scripture as well.

Sometimes, if we use too much reason in our approach to Scripture, we find ourselves reasoning it all away and it becomes nothing but a quaint book of myths, morals and legends.

Yes, the Scriptures are not without flaws.

As God-inspired as they might be, they were written by fallible human beings.

Pre-scientific human beings, writing in a language that has been translated and retranslated over and over again.

I hate to break the news to you, but God didn’t set down a perfectly formed Bible, written in stone and perfect King James English in our midst.

And human beings have been notorious—even in Scripture—of not always being able to get everything perfect, no matter how God-inspired they are.

But, the second part our explanation of the question from the Catechism of why we call Holy Scripture the Word of God is even more important to me.

“God still speaks to us through scripture.”

I love the idea that God does still speak to us through these God-inspired writings by flawed human beings.

And what God speaks to us through Scriptures is, again and again, a message of love and justice, even in the midst of some of the more violent, or fantastic stories we read in Scripture.

Our Gospel reading is a prime example of that.

What does the widow in Jesus’ parable pray?

“Grant me justice against my opponent,” she prays.

This also a truly interesting story.

This widow, who would not take no for an answer, persisted.

This widow, who, in that time and place without a man in her life was in bad shape, was demanded to be heard.

This widow who had been taken advantage of (someone cheated her of her rightful inheritance) did not let discouragement stop her.

This widow prayed day and night.

And what happened?

God heard her and turned the hearts of the unjust.

That, definitely, speaks to us right now.

That is what we should be praying for right now in this country.

See, God is definitely speaking loudly here to us through this scripture.

We are to pray for justice, not only against our opponents.

But we should be praying for justice in this country and this world.

Please, God, turn the hearts of the unjust! And grant us justice!

The scriptural definition of “justice” is “to make right.”

So, to seek justice from God means that something went wrong in the process, and we long for “rightness.”

We too need to be praying hard, over and over again, for justice.

God also seems to be speaking loud and clear through Paul, himself a very flawed human being, in his letter to Timothy.

“All scripture is inspired by God,” Paul instructs, “and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that everyone who belongs to God may be proficient, equipped for every good work.”

I love that. That is some rational, solid thinking, if you ask me.

Scripture here is intended not to condemn, not bash, not to hurt, but to build up and equip us for “every good work.”

“Proclaim the message, “ he tells Timothy (and us), “be persistent whether the time is favorable or unfavorable; convince, rebuke, and encourage, with the utmost patience in teaching.”

For any of us who have been teachers, those words strike home.

But, if you notice, nowhere does Paul say we must condemn or pound down, or coerce others using Scripture.

Scripture must build up and encourage and teach us to serve and to love.

And Scripture must be a conduit through which God continues to speak to us.

Yes, our encounter with God in scripture sometimes is very much like Jacob wrestling with angel.

If scripture doesn’t do things for us sometimes, if we only go to scripture to feel good about ourselves, to prove ourselves right about things, and not be challenged, then we are using scripture incorrectly and it may, in fact, come back to cut us.

So, let us embrace this balanced and reasonable and very Anglican approach to Scripture.

Let us listen to Scripture and hear the Word of God speaking to us through it.

Let us continue to place the Scriptures at the center of our lives and let us allow them to guide us into a pathway of love and service.

And, most importantly, let us use it, again and again, as an instrument of love rather than a weapon of war and hatred.

When we do, we will find that the two-edged sword of that instrument of love, will open the doors of God’s love to us as well.

October 9, 2022

18 Pentecost

October 9, 2022

+ As a poet, I find myself obsessing over words on occasion.

As in a particular word

There are certain words I find myself examining.

Often there are words I find myself examining like a little jewel, turning it around and weighing it and considering it like it’s a brand new word.

One of those words I’ve recently enjoyed re-examining is the word “Mercy.”

It’s a beautiful word!

It flows!

And I love the fact that, in French, the word for “Thank you” is “merci.”

Mercy is something we tend to overlook.

Certainly in regard to others.

But let me tell you, it is not something we overlook when it comes to us.

To be on the receiving end of mercy is a wonderful thing!

Mercy is like a fresh wonderful breeze on our face, especially if it is something we are being granted after a hardship in our lives.

Mercy is not something we think of too often in our lives, certainly not on a daily basis.

But for Jesus and those Jewish people of his time, mercy was an important part of their understanding of the world and their relationship with God.

Tonight, at sundown, the Jewish feast of Sukkot begins

Sukkot is an important feast in Judaism.

It is also called “The feast of Booths,” which refers to the tents the Israelites lived in during their 40 years in the desert.

In fact, in some Jewish homes, a tent is often set up during this high holy day as a commemoration of the feast.

On the Feast of Sukkot, the “Great Hallel” is prayed.

Hallel means “praise,” and refers to the group of psalms recited at the time of the new moon, as well on feasts like Sukkot, which commemorates the period of time the Tribe of Israel spent in the desert on their way to the Promised Land.

“Hallel” is the refrain from Psalm 136 that says,

“for God’s mercy endures forever.”

It is believed that Jesus himself would have sang the Great Hallael with his disciples when they went to the Mount of Olives after the Last Supper on the night before his death.

Now, mercy in this context means more than just forgiveness or some kind of reprieve

Mercy also means, in a Jewish understanding of the word, such things as God’s enduring love for Israel and the mercy that goes with that love.

Mercy also means, in this context, behaving in a particular way.

It means being ethical and being faithful to God’s will.

Mercy.

It’s an incredible word.

And it is so packed with meaning and substance!

And it’s one that I think sums up so many of the prayers we pray.

Certainly, the prayers I pray.

In those moments in which I am overwhelmed or exhausted or anxious or simply don’t know what to pray, I often find myself just praying, Please, God, have mercy on me, or on the person for whom I’m praying.

Today, in our Gospel reading, we find that word, Mercy, in a very prevalent place.

In fact the petition the leper makes to Jesus is a powerful one.

“Jesus, Master, have mercy on me!”

And what does Jesus do?

He does just that.

He has mercy on him.

And, by doing so, Jesus sets the tone for us as well.

Just as Jesus showed mercy, so should we show mercy again and again in our own lives.

We see, in our Gospel reading today, mercy in action.

And it is a truly wonderful thing!

These lepers are healed.

But, before we lose track of this story, let’s take a little deeper look at what is exactly happening.

Now, first of all, we need to be clear about who lepers were in that day.

Lepers, as we all know, were unclean.

But they were worse than that.

They were contagiously unclean.

And their disease was considered a very severe punishment for something.

Sin of course.

But whose sin?

Their own sin?

or the sins of their parents? Or grandparents?

So, to even engage these lepers was a huge deal.

It meant that to engage them meant to engage their sin in some way.

But, the real interesting aspect of this story is one that you might not have noticed.

The lepers themselves are interesting.

There are, of course, ten of them.

Nine lepers who were, it seems, children of Israel.

And one Samaritan leper.

Now a Samaritan, for good Jews like Jesus, would have been a double curse.

It was bad enough being a leper.

But to be a Samaritan leper was much worse.

Samaritans, as also know, were also considered unclean and enemies.

They didn’t worship God in the same way that good, orthodox Jews worshipped God.

They had turned away from the Temple in Jerusalem.

And they didn’t follow the Judaic Law that Jews of Jesus’ time strived to follow.

But the lepers, knowing who they are and what they are, do the “right” thing (according to Judaic law).

Again and again, throughout the story they do the right thing.

They first of all stand far off from Jesus and the others.

That’s what contagious (unclean) people do.

And when they are healed, the nine again do the right thing.

They heed Jesus’ words and, like good Jews, they head off to the priest to be declared clean.

According to the Law, it was the priest who would examine them and declare them “clean” by Judaic Law.

But they do one “wrong” thing before they do so.

Did you notice what thing they didn’t do?

Before heading off to the priest, they don’t first thank Jesus.

Only the Samaritan stays.

And the reason he stays is because, as a Samaritan, he wouldn’t need to approach the Jewish priest.

So, he turns back.

And he engages this Jesus who healed him.

He comes back, praising God and bowing down in gratitude before Jesus.

After all, it is through Jesus that God has worked this amazing miracle!

But Jesus does not care about this homage.

He is irritated by the fact the others did not come back.

Still, despite his irritation, if you notice, his mercy remained.

Those ungrateful lepers—along with the Samaritan—remain healed.

Despite their ingratitude, they are still healed.

That is how mercy works.

The interesting thing for us is, we are not always so good at mercy.

We are good as being vindictive, especially to those who have wronged us.

We are very good as seeking to make others’ lives as miserable as our lives are at times.

If someone wrongs us, what do we want to do?

We want to get revenge.

We want to “show them.”

After all, THAT is what they deserve, we rationalize.

But, that is not the way of Jesus.

If we follow Jesus, revenge and vindictive behavior is not the way to act.

If we are followers of Jesus, the only option we have toward those who have wronged us is…mercy.

Still, even then, we are not so good at mercy, especially mercy to those who have turned away from us and walked away after we have done something good for them.

It hurts when someone is an ingrate to us.

It hurts when people snub us or ignore us or return our goodness with indifference.

In those cases, the last thing in the world we are thinking of is mercy for them.

Of course, none of us are Jesus.

Because Jesus was—and is—a master at mercy.

And because he is, we, as followers of Jesus, are challenged.

If the one we follow shows mercy, we know it is our job to do so as well.

No matter what.

No matter if those to whom we show mercy ignore us and walk away from us.

No matter if they show no gratitude to us.

No matter if they snub us or turn their backs to us or ignore us.

Our job is not to concern ourselves with such things.

Our job, as followers of Jesus, is simply to show mercy again and again and again.

And to seek mercy again and again and again.

Have mercy on me, we should pray to God on a regular basis.

God, have mercy on me.

Please, God, have mercy on me.

Please, God, have mercy on my loved ones.

Please, God, have mercy on St. Stephen’s.

Please, God, have mercy on our country.

Please, God, have mercy on our planet.

This is our deepest prayer.

This is the prayer of our heart.

This is the prayer we pray when our voices and minds no longer function perfectly.

This is the prayer that keeps on praying with every heartbeat within us.

And by praying this prayer, by living this prayer, by reflecting this prayer to others, we will know.

We will know—beyond a shadow of doubt—that we too can get up.

We too can go our way.

We too can know that, yes, truly our faith has made us well.

Let us pray.

Holy God, your mercy truly does endure forever. Have mercy on us, who call on you in moments of despair or anxiety and depression or pain. Have mercy on us who cry out to you from the depths of the darkness of our lives. Let your mercy rain down on us as sweet manna, and let us rejoice in that mercy now and forever. In Jesus’ name, we pray. Amen.

October 2, 2022

17 Pentecost

October 2, 2022

Luke 17.5-10

+ Yesterday was a big day in my life.

Yesterday I celebrated 14 years as Priest of St. Stephen’s.

I became the Priest here on October 1, 2008.

And in that time, we have some major changes.

I always joke that in that time, I feel like I have been pastor of three different parishes.

I found myself pondering what St. Stephen’s means to me.

As I did, I was thinking about the fact that one thing I very proud of here is that when we say we are truly welcoming and inclusive, we really are a welcoming and inclusive parish.

We welcome everyone and we include everyone, even people who might not believe the same things about certain issues.

People who have different political views.

People who have different spiritual views.

Yet, despite that description, there truly is a wide spectrum of belief here at St. Stephen’s.

We encompass many people and beliefs here.

And I love that!

And, even people who don’t believe, or don’t know what they believe, are always welcome here.

And included.

That includes even atheists.

I love atheists, as many of you know.

And I don’t mean, by saying that, that I love them because of some intent to convert them.

No.

My love for atheists has simply to do with the fact that I “get” them.

I understand them.

I appreciate them.

And I have lots of atheists in my life!

Agnostics and atheists have always intrigued me.

In fact, as many of you know, I was an agnostic, verging on atheism, once a long time ago in my life.

Now to be clear, agnosticism and atheism are two similar though different aspects of belief or disbelief.

An agnostic—gnostic meaning knowledge, an “a” in front of it negates that word, so no knowledge of God—is simply someone who doesn’t know if God exists or not.

An atheist—a theist is a person who believes in a god, an “a” in front of it negates it, so a person who does not believe a god—in someone who simply does not or cannot believe.

You have heard me say often that we are all agnostics, to some extent.

There are things about our faith we simply—and honestly—don’t know.

That’s not a bad thing.

It’s actually a very good thing.

Our agnosticism keeps us on our toes.

I think agnosticism is an honest response.

But atheism is interesting and certainly honest too, in this sense.

Whenever I ask an atheist what kind of God they don’t believe in, and they tell me, I, quite honestly, have to agree.

When atheists tell me they don’t believe in some white-bearded man seated on a throne in some far-off, cloud filled kingdom like some cut-out, some magic man living in the sky from Monte Python’s Search for the Holy Grail, then, I have to say, “I don’t believe in that God either.”

I am an atheist in regard to that God—that idolatrous god made in our own image.

If that’s what an atheist is, then count me in.

But the God I do believe in—the God of mystery, the God of wonder and faith and love—now, that God is a God I can serve and worship.

And this God of mystery and love that I serve has, I believe, reaches out to us, here in the muck of our lives.

Certainly that is not some distant, strange, human-made God.

Rather it is a close, loving, God, a God who knows us and is with us.

But there are issues with such a belief.

Believing in a God of mystery means we now have work cut out for us in cultivating our faith in that God of mystery.

“Increase our faith!” the apostles petition Jesus in today’s Gospel.

And two thousand years later, we—Jesus’ disciples now—are still asking him to essentially do that for us as well.

It’s an honest prayer.

We want our faith increased.

We want to believe more fully than we do.

We want to believe in a way that will eliminate doubt, because doubt is so…uncertain.

Doubt is a sometimes frightening place to explore.

And we are afraid that with little faith and a lot of doubt, doubt will win out.

We are crying out—like those first apostles—for more than we have.

But Jesus—in that way that Jesus does—turns it all back on us.

He tells us that we shouldn’t be worrying about increasing our faith.

We should rather be concerned about the mustard seed of faith that we have right now.

Think of that for a moment.

Think of what a mustard seed really is.

It’s one of the smallest things we can see.

It’s a minuscule thing.

It’s the size of a period at the end of a sentence or a dot on a lower-case I (12 point font).

It’s just that small.

Jesus tells us that with that little bit of faith—that small amount of real faith—we can tell a mulberry tree, “be uprooted and planted in the sea.”

In other words, those of us who are afraid that a whole lot of doubt can overwhelm that little bit of faith have nothing to worry about.

Because even a little bit of faith—even a mustard seed of faith—is more powerful than an ocean of doubt.

A little seed of faith is the most powerful thing in the world, because that tiny amount of faith will drive us and push us and motivate us to do incredible things.

And doing those things, spurred on and nourished by that little bit of faith, does make a difference in the world.

Even if we have 99% doubt and 1% faith, that 1% wins out over the rest, again and again.

We are going to doubt.

We are going to sometimes gaze into that void and have a hard time seeing, for certain—without any doubt—that God truly is there.

We all doubt.

And that’s all right to do.

But if we still go on loving, if we still go on serving, if we still go on trying to bring the sacred and holy into our midst and into this world even in the face of that 99% of doubt, that is our mustard seed of faith at work.

That is what it means to be a Christian.

That is what loving God and loving our neighbor as ourselves does.

It furthers the Kingdom of God in our midst, even when we might be doubting that there is even a Kingdom of God.

Now, yes, I understand that it’s weird to hear a priest get up here and say that atheists and agnostics and other doubters can teach us lessons about faith.

But they can.

I think God does work in that way sometimes.

I have no doubt that God can increase our faith by any means necessary, even despite our doubts.

I have no doubt that God can work even in the mustard-sized faith found deep within someone who is an atheist or agnostic.

And if God can do that in the life and example of an atheist, imagine what God can do in our lives—in us, who are committed Christians who stand up every Sunday in church and profess our faiths in the Creed we are about to recite together.

So, let us cultivate that mustard-sized faith inside us.

Let’s not fret over how small it is.

Let’s not worry about weighing it on the scale against the doubt in our lives.

Let’s not despair over how miniscule it is.

Let’s not fear doubt.

Let us not be scared of our natural agnosticism.

Rather, let us realize that even that mustard seed of faith within us can do incredible things in our lives and in the lives of those around us.

And in doing those small things, we all arebringing the Kingdom of God into our midst.

Let us pray.

Holy and loving God, increase our faith; help us to cultivate the kernel of faith we carry with us, and make us truly aware of our love and your Presence in our lives; in Jesus’ name we pray. Amen.

September 25, 2022

16 Pentecost

September 25, 2022

Ok.. . .I weirdly love the parable we heard today.

I think I might be one of the very few people who do actually love it.

For some, it’s just so weird and…well, bizarre.

It’s such an interesting story.

There’s just so much good stuff, right under the surface of it.

So, let’s take a look at it.

In it, we find Lazarus.

Now, if you notice, it’s the only time in Jesus’ parables that we find someone given a name—and the name, nonetheless, of one of Jesus’ dearest friends. In most of Jesus’ parables, the main character is simply referred to as the Good Samaritan or the Prodigal Son.

But here we have Lazarus.

And the name actually carries some meaning.

It means “God has helped me.”

Now the “rich man” in this story is not given a name by Jesus, but tradition has given him the name Dives, or “Rich Man”

Between these two characters we see such a juxtaposition.

We have the worldly man who loves his possessions and is defined by what he owns.

And we have Lazarus who is poor, who seems to get sicker and hungrier all the time.

In fact, his name almost seems like a cruel joke.

It doesn’t seem like God has helped Lazarus at all.

The Rich Man sees Lazarus, is aware of Lazarus, but despite his wealth, despite all he has, despite, even his apparent happiness in his life, he can not even deign to give to poor Lazarus a scrap of food from all that he has.

Traditionally of course, we have seen them as a very fat Rich Man, in fine clothing and a haughty look and a skinny, wasted Lazarus, covered in sores, which I think must be fairly accurate to what Jesus hoped to convey.

They are opposite, mirror images of each other.

But there are some subtle undercurrents to this story.

Lazarus is not without friends or mercy in his life. In fact, it seems that maybe God really IS helping him.

He is not quite the destitute person we think he is.

First of all, we find him laid out by the Rich Man’s gate.

Someone must’ve put him there, in hopes that Rich Man would help him. Someone cared for Lazarus, and that’s important to remember.

Second of all, we find these dogs who came to lick his sores.

The presence of dogs is an interesting one.

Are they just wild dogs that roam the streets, or are they the Rich Man’s watch dogs?

New Testament theologian Kenneth Bailey has mentioned that dog saliva was believed by people at this time to have curative powers. (We now know that is definitely NOT the case)

So, even the dogs are not necessarily a curse upon Lazarus but a possible blessing in disguise.

Finally, when Lazarus dies, God receives him into paradise.

In fact, as we hear, “angels carried him to be with Abraham.”

The Rich Man dies and goes to Hades—or the underworld. Lazarus goes up, Dives goes down.

The Rich Man, in the throes of his torment, cries out to Father Abraham.

And Abraham, if you notice, doesn’t ignore him or turn his back on him, despite the fact that the Rich Man did just that to Lazarus.

Abraham

does not even really scold him.But he does let him know that those who are still alive will not listen to someone raised from the dead, just as they did not listen to Moses and the prophets.

This is all obviously an allusion to Jesus' own death and resurrection.

There really is a beauty to this story and a lesson for us that is more than just the bad man gets punished while the good man gets rewarded.

And it is also not really about heaven and hell either.

I get a lot of people who, when they hear that I do not believe in an eternal hell, remind me of this parable.

I, in turn, remind them that it is a parable.

It is a story that Jesus is telling.

He is not talking about literal people here.

And he is not talking about literal places.

It is poetry and poetic imagery.

And that is vital to remember.

What we find is that, by the world’s standards, by the standards of those who are defined by the material aspects of this life, Lazarus was the loser before he died and the Rich Man was the winner, even despite his callousness.

And the same could be said of us as well. It might seem, at moments, as though we are being punished by the things that happen to us.

It is too easy to pound our chests and throw dirt and ashes in the air and to cry out in despair and curse God when bad things happen.

It is much harder to recognize that while we are there, at the gate outside the Rich Man’s house, lying in the dirt, covered in sores, that there are people who care, that there are gentle, soothing signs of affection, even from dogs.

Actually, there have been times when I have been soothed more by dogs than humans.

And it is hard sometimes in those moments to see that God too cares.

I have done that.

I have actually done that not all that long ago in my own life.

Since we’re discussing last things this morning, since we’re talking about heaven and hell and feeling sometimes as though God does not care, let’s take it up a notch.

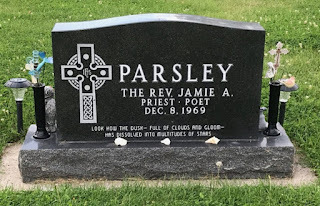

As many of you know, I do have a gravestone.

My gravestone is actually entirely inscribed, save for the last final date of my life.

You can actually go and see it if you’d like.

And it’s actually the backside of my parents’ gravestone.

And if you want to see some defiance even in death, notice as you look at it that it n has a Celtic cross on it.

I’m kind of proud of the fact that among all those Swedish Lutherans, there is a Celtic cross on my stone.

But what people who see my gravestone take note of is the epitaph I chose for myself.

It’s actually the final line of a poem I wrote toward the end of my “cancer experience” 20 years ago which felt to me very much like a Lazarus experience.

The poem was written as my father and I were driving to Minot on a particularly cold night 20 years ago next months, in October 2002 shortly after the first snow fall of the year.

We were driving up there for my final interview with the Commission on Ministry before I was ordained to the Diaconate.

As we neared the city and came up over a hill, I could see the city laid out below us.

Above us, the sky had cleared after a particularly gray and gloomy day.

When the clouds had cleared, we could see the stars, which, on that cold night, looked especially crisp and clear.

And in that moment, after all that I had went through with my cancer, I suddenly knew for the first time, that, somehow, everything was going to be fine.

At the end of that poem, I wrote what would become the epitaph on my stone.

I wrote in that poem, “Dusk” (I’m not going to inflict the whole poem on you, but it’s in my book, Just Once, which I’m giving away for free):

“…I look up into the sky

and see it—a transformation

so subtle I almost didn’t notice it

as I sit there trembling

behind the tinted windshield.

I say to myself

‘Look! Just look!

Look how the dusk—

full of clouds and gloom—

has dissolved into

multitudes of stars!’”

My epitaph is just that:

Look how the dusk—

full of clouds and gloom—

has dissolved into

multitudes of stars!’”

To some extent, that’s what it’s like to be a Christian.

To some extent, that’s what it’s like: when we think the darkness and the gloom has encroached and has won out, we can look up and see those bright sparks of light and know, somehow, that it’s all going to be all right.

And in those moments, we can remember one important thing:

Paradise awaits us.

That place to which Lazarus was taken by angels awaits us and, for those of us striving and struggling through this life, we can truly cling to that hope.

For those of us still struggling, we can set our eyes on the prize, so to speak and move forward.

We can work toward that place, rather than “diving” like Dives himself, into the pit of destruction he essentially created for himself.

In a real sense, the Rich Man was weighed down by his wealth, especially when he refused to share it, and he ended up wallowing in the mire of his own close-mindedness and self-centeredness.

What happens to this Rich Man?

Well, the chickens came home to roost.

The rich man, full of hubris and pride, full of arrogance and selfishness and self-centeredness.

The rich man, who did not care for the poor, who ignored the needy, who cared only for himself,

The rich man who boasted and blew smoke and walked around with his puffed-out chest,

The rich man fell, as all such people we find will fall.

Scripture again and again tells us such people will fall.

History again and again tells us such people will fall.

The chickens ALWAYS come home to roost.

The moral of this parable is this: let us not be like the rich man.

Let us not follow that slippery, dangerous slope to destruction.

But for those of us who, in the midst of our struggles, can still find those glimmers of light in the midst of the gloom, we are not weighed down.

We are freed in ways we never knew we could be.

We are lifted up and given true freedom.

We are Lazarus.

God has truly helped us.

And God continuous to help us again and again.

And when God does help us, it is then that we see moist clearly those multitudes of light shining brightly in the occasional gloom of our lives.

Let us pray.

Loving God, open our minds and our hearts that we may always be willing to serve those who need to served and help those who need to be helped. Make us truly aware of those around who cry out, however silently, for help, so that we may do what you call us do in this world; in Jesus’ name, we pray. Amen.

September 18, 2022

15 Pentecost

September 18, 2022

Amos 8.4-7;1 Timothy 2.1-7; Luke 16.1-13

+ Yesterday was an important feast day in the church, and for us here at St. Stephen’s.

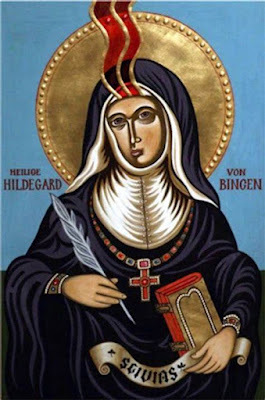

It was the feast of St. Hildegard of Bingen.

Oh, how we love St. Hildegard!

We love her because she was something else!

She was a defiant force.

And she was one of the first feminists.

In fact, we love St. Hildegard so much that we even named our bell after her.

St. Hildegard was a German Benedictine nun, a mystic.

She was also a great musician, which is also another reason why she is the namesake for our bell.

But the real reasons she was chosen as the patron saint of our bell is because she was quite the force to be reckoned with.

And let me tell you, St. Hildegard would’ve loved St. Stephen’s and all it stands for.

She would fit in very well here.

At a time when women were not expected to speak out, to challenge, to stand up—well, Hildegard most definitely did that.

She was an Abbess, she was in charge of a large monastery of women, and as such she held a lot of authority.

An abbess essentially had as much authority in her monastery as a Bishop had in his diocese.

She even was able to have a crosier—the curved shepherd’s crook—that is normally reserved for a bishop.

And she definitely put Bishops and kings in their place.

There is a very famous story that when the emperor, Fredrick Barbarossa supported three of the anti-popes who were ruling in Avignon at that time, she wrote him a letter.

My dear Emperor,

You must take care of how you act.

I see you are acting like a child!!

You live an insane, absurd life before God.

There is still time, before your judgment comes.

Yours truly,

Hildegard.

That is quite the amazing thing for a woman to have done in her day.

Even more amazing is that the emperor heeded her letter.

And as a result of that letter, she was invited by the Emperor to hold court in his palace.

By “judgement” here, Hildegard is making one thing clear in her letter.

There are consequences to our actions.

And God is paying attention.

For us, we could say it in a different way.

If you know me for any period of time, you will hear me say one phrase over and over again, at least regarding our actions.

That phrase is “The chickens always come home to roost.”

And it’s true.

One of the things so many of us have had to deal with in our lives are people who have not treated us well, who have been horrible to us, who have betrayed us and turned against us.

It’s happened to me, and I know it’s happened to many of you.

It is one of the hardest things to have to deal with, especially when it is someone we cared for or loved or respected.

In those instances, let’s face it, sometimes it’s very true.

“The chickens do come home to roost.”

Or at least, we hope they do.

Essentially what this means is that what goes around, comes around.

We reap what we sow.

There are consequences to our actions.

And I believe that to be very true.

And not just for others, who do those things to us.

But for us, as well.

When we do something bad, when we treat others badly, when gossip about people, or trash people behind their backs, who disrespect people in any way, we think those things don’t hurt anything.

And maybe that’s true.

Maybe it will never hurt them.

Maybe it will never get back to them.

But, we realize, it always, always hurts us.

And when we throw negative things out there, we often have to deal with the unpleasant consequences of those actions.

I know because I’ve been there.

I’ve done it.

And I’ve paid the price for it.

But there is also a flip side to that.

And there is a kind of weird, cosmic justice at work.

Now, for us followers of Jesus, such concepts of “karma” might not make as much sense.

But today, we get a sense, in our scriptures readings, of a kind of, dare I say, Christian karma.

Jesus’ comments in today’s Gospel are very difficult for us to wrap our minds around.

But probably the words that speak most clearly to us are those words, “Whoever is faithful in a very little is faithful in much.”

Essentially, Jesus is telling us this simple fact: what you do matters.

There are consequences to our actions.

There are consequences in this world.

And there are consequences in our relation to God.

How we treat each other as followers of Jesus and how we treat others who might not be followers of Jesus.

How we treat people who might not have the same color skin as we do, or who are a different gender than us, or how we treat someone who are a different sexual orientation from our own.

What we do to those people who are different than us matters.

It matters to them.

And, let me tell you, it definitely matters to God.

We have few options, as followers of Jesus, when it comes to being faithful.

We must be faithful.

Faithful yes in a little way that brings about great faithfulness.

So, logic would tell us, any increase of faithfulness will bring about even greater faithfulness.

Faithfulness in this sense means being righteous.

And righteousness means being right before God.

Jesus is saying to us that the consequences are the same if we choose the right path or the wrong path.

A little bit of right will reap much right.

But a little bit of wrong, reaps much wrong.

Jesus is not walking that wrong path, and if we are his followers, then we are not following him when we step onto that wrong path.

Wrongfulness is not our purpose as followers of Jesus.

We cannot follow Jesus and willfully—mindfully—practice wrongfulness.

If we do, let me tell you, the chickens come home to roost.

We must strive—again and again—in being faithful.

Faithful to God.