Susan Appleyard's Blog, page 22

July 24, 2015

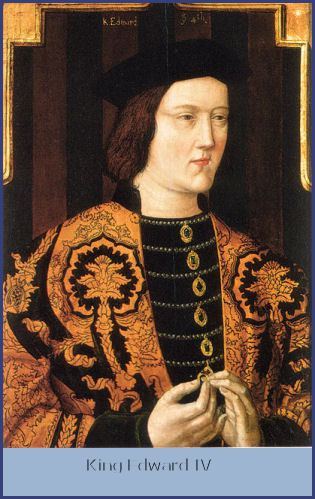

Edward IV the merchant king by Susan Appleyard

When he ascended the throne, Edward was poorer than a church mouse. Not only did he inherit his father’s debts, but also took upon himself the debts of Henry VI. At the close of Henry’s reign the Crown’s indebtedness amounted to nearly four hundred thousand pounds. Some of those debts had been outstanding for years. Matters had reached the point where no one was prepared to invest in the government, even at exorbitant rates of interest. To put this figure in some perspective, Henry’s income at that time amounted to little more than thirty-three thousand pounds. It had been eroded by his well known practice of alienating Crown lands, wardships and other sources of revenue to reward those often little deserving of reward. He could never have recovered.

Edward had no choice but to assume his rival’s obligations because he was canny enough to realize that if a man should decide the only way he would get his money back was if Henry was restored to power, then clearly it was in his interest to support Henry.

Furthermore, in those early years Edward had expensive campaigns to fight against the erstwhile king and queen. And he wanted a splendid court to show visiting dignitaries that England under him was growing in prosperity and power. But where was the money for all this to come from? Parliament provided some ‘for the defense of the realm’ not all of which was used for the purpose intended, but we won’t go there.

Very early in his reign Edward, who was nothing if not innovative, decided to become a merchant. While in Calais with Warwick, and in London, too, he would have met the Celys, the Canynges, the Cooks and other fabulously wealthy merchants who lived like princes – well, earls anyway – and likely influenced him to try his hand.

At first he exported wool and woolfells, which, being of the finest quality, were much in demand for making into cloth, particularly in Flanders. Although wool was in its heyday, cloth manufacturing was burgeoning, and soon he was exporting English cloth, dyed and undyed, as well as tin, lead, pewter vessels, wheat, rye and beans and lambskins. Imports included treacle – yes, treacle – paper, oil, woad, alum, wax, complete harnesses, wine and wormseed, even a popinjay, among a variety of other products.

To give some idea how busy he was , in February 1470, just as he was dealing with Warwick’s second rebellion, 25 ships entered or left the port of London alone, carrying goods belonging to the king. His loss of the throne caused only a brief interruption in his mercantile endeavors. He was soon back in business.

Nor was he alone in dabbling his august fingers in the vulgar business of trade. What was good enough for the king was good enough for the Duchess of York, the Earl of Warwick and his brother George, the Earl of Essex, Lords Hastings, Howard, Duras, Fauconberg and Mountjoy.

It paid off. He was the first King of England to die solvent since Henry II.

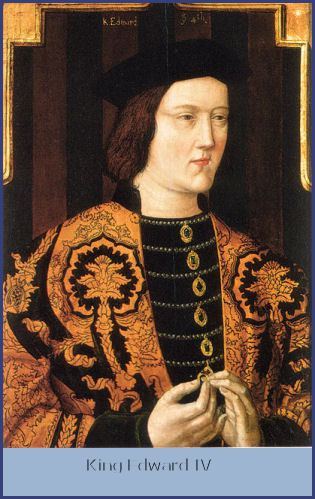

Edward IV the merchant king

When he ascended the throne, Edward was poorer than a church mouse. Not only did he inherit his father’s debts, but also took upon himself the debts of Henry VI. At the close of Henry’s reign the Crown’s indebtedness amounted to nearly four hundred thousand pounds. Some of those debts had been outstanding for years. Matters had reached the point where no one was prepared to invest in the government, even at exorbitant rates of interest. To put this figure in some perspective, Henry’s income at that time amounted to little more than thirty-three thousand pounds. It had been eroded by his well known practice of alienating Crown lands, wardships and other sources of revenue to reward those often little deserving of reward. He could never have recovered.

Edward had no choice but to assume his rival’s obligations because he was canny enough to realize that if a man should decide the only way he would get his money back was if Henry was restored to power, then clearly it was in his interest to support Henry.

Furthermore, in those early years Edward had expensive campaigns to fight against the erstwhile king and queen. And he wanted a splendid court to show visiting dignitaries that England under him was growing in prosperity and power. But where was the money for all this to come from? Parliament provided some ‘for the defense of the realm’ not all of which was used for the purpose intended, but we won’t go there.

Very early in his reign Edward, who was nothing if not innovative, decided to become a merchant. While in Calais with Warwick, and in London, too, he would have met the Celys, the Canynges, the Cooks and other fabulously wealthy merchants who lived like princes – well, earls anyway – and likely influenced him to try his hand.

At first he exported wool and woolfells, which, being of the finest quality, were much in demand for making into cloth, particularly in Flanders. Although wool was in its heyday, cloth manufacturing was burgeoning, and soon he was exporting English cloth, dyed and undyed, as well as tin, lead, pewter vessels, wheat, rye and beans and lambskins. Imports included treacle – yes, treacle – paper, oil, woad, alum, wax, complete harnesses, wine and wormseed, even a popinjay, among a variety of other products.

To give some idea how busy he was , in February 1470, just as he was dealing with Warwick’s second rebellion, 25 ships entered or left the port of London alone, carrying goods belonging to the king. His loss of the throne caused only a brief interruption in his mercantile endeavors. He was soon back in business.

Nor was he alone in dabbling his august fingers in the vulgar business of trade. What was good enough for the king was good enough for the Duchess of York, the Earl of Warwick and his brother George, the Earl of Essex, Lords Hastings, Howard, Duras, Fauconberg and Mountjoy.

It paid off. He was the first King of England to die solvent since Henry II.

July 18, 2015

The Pastons and their copious correspondence.

The Pastons of Norfolk are famous today because of the legacy of letters they have left us, dating between the years 1422 to 1509. The collection, numbering more than a thousand letters and other documents, passed from the executors of William Paston, 2nd. Earl of Yarmouth, into various hands and the bulk eventually ended up in the British Library, with a few letters in the Bodleian Library, Oxford; at Magdalen College, Oxford, and Pembroke College, Cambridge.

St. Margaret’s Church Norwich, where many of the Pastons are buried.

Several Pastons contributed to the collection, but the most interesting for me is the period covered by the three Johns. John the father, Sir John, and John the Younger. (The latter two were brothers. What possessed John the father to name two sons after himself is a mystery, but he must have created a nightmare for those who have studied the letters and tried to figure out which John was referred to.) These 3 Pastons lived during a fascinating and turbulent time – the War of the Roses, although their letters add little of value to our store of knowledge of the period. The two brothers fought at the battle of Barnet, in which John the Younger was wounded. Both were soon pardoned by a magnanimous King Edward.

It was during this time that most of the letters were written. Some were written by Paston servants or friends. The women got in the act also, although their letters were probably written by clerks. So you may read, in the same letter, business matters mixed with news of the latest dispute and a bit of Norfolk gossip; a scolding for a son who is not doing as well as expected, along with a request for some cloth or a spice that’s cheaper in London than Norfolk. This is the real value of the letters; they give an intriguing peek into the life of a typical (well, maybe not so typical) English middle-class family. There are nuggets of pure gold to be mined in these letters.

Also, the Pastons had some adventures of their own. It all began with Sir John Fastolf (not to be confused with Sheakspear’s Falstaff, who was supposedly modeled after him). Richer than many an earl, he had made his fortune during the war with France. On his deathbed he changed his will, (which is never a good thing to do) naming his lawyer and land agent John Paston the father as heir and executor, which led to years and years of litigation and worse ills with disappointed heirs and previous executors, as well as the sometime enmity of such powerful figures as the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk. Paston fortunes fluctuated with the vicissitudes of Edward IV and the fortunes of the two dukes. John the father was imprisoned three times; contending parties fought over Caister Castle, the jewel of Fastolf’s bequest, and other properties; Margaret Paston was once ejected physically from a house so that others could take possession; there were brawls in the street, stabbings – Oh, it was a fine example of land-greed in the fifteenth century.

But the Pastons prevailed in the end because, as noted above, two centuries later they were earls, while the Mowbrays of Norfolk and the de la Poles of Suffolk were nowhere to be found in the English peerage.

Sources: A Medieval Family by Frances and Joseph Gies

Wikipedia

July 10, 2015

Another excerpt

It’s the weekend again, so time for another excerpt. This one is from my third and latest book. Have a look under the cover The Remorseless Queen or click on the title above.

July 6, 2015

Bishop Stillington: A key role or a bit player?

Robert Stillington was Dean of St. Martin le Grande (a church where he later sought sanctuary) and became, briefly, under Henry VI, Keeper of the Privy Seal, a role he continued in under Edward IV. In 1466, he was consecrated as Bishop of Bath and Wells, and the following year he was promoted to Lord Chancellor, a post he held (with a short break) until his resignation in 1473. In ’75 he accompanied the king on his expedition to France and that same year was summoned to Rome to answer charges, the nature of which I’ve been unable to discover. Possibly he had been neglecting his pastoral duties in favor of his secular ones.

In 1478 he was sent to the Tower of London. Some have speculated that whilst there he mumbled a certain secret to the Duke of Clarence, and that was the real reason Clarence was put to death – and nothing whatever to do with the multiplicity of treason charges against him. Oh, right, and after killing his brother Edward let the bishop go to spread such potentially dynasty-destroying information far and wide!

A less popular theory is that Clarence whispered the secret to Stillington. Neither one can possibly have happened because Stillington didn’t arrive at the Tower until a few days after Clarence had been carried out of his bier. (Stonor letters II-42) Well then, perhaps the secret was passed between them before either one saw the inside of the Tower as a prisoner. This is even more unlikely. If Clarence had been in possession of such information he would have used it to defame and damage his brother or I do not know my Clarence.

Why was Stillington imprisoned? According to his pardon he was accused of violating his oath of fidelity by speaking out against the king, but upon being examined before the king and certain lords ecclesiastical and temporal he was able to prove his innocence and released after a few weeks. Gairdner (Richard III 90) would have us believe that he had offended King Edward by trying to persuade him to make amends to Lady Eleanor Talbot/Butler, to whom the king had once proposed marriage in Stillington’s presence. Consider that Edward had been married for fully fourteen years and Lady Eleanor in her grave for fully ten years, so no amount of amends was going to do her any good, and you can’t help wondering why the good bishop waited to long to raise the issue.

However, no one is terribly interested in the bishop’s early years. It is only in 1483 that he becomes of real interest, because then, so we are told ad nauseum, he placed evidence before Richard of Gloucester that proved King Edward – then recently deceased and unable to defend himself – had been precontracted to the aforementioned Lady Eleanor, a daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury; therefore it followed that King Edward and Queen Elizabeth lived together ‘sinfully and damnably’ and the issue were bastards and could not inherit the throne. Evidence! I hear/read the word all over and yet when I ask simple questions like: What was the evidence? What did it consist of? When was it given? I am deafened by silence.

According to Alison Weir, the first account we have concerning Bishop Stillington and the precontract comes from Philippe de Commines, a French chronicler, who did not begin writing his memoirs until 10 years after the relevant events. Amazing! Ten years of silence from the English chroniclers, letter writers, official records etc! Commines writes that on June 8th Stillington appeared before the council and revealed that King Edward had promised marriage to Lady Eleanor on condition that he might lie with her. The lady had assented and the bishop performed the ceremony with only himself and the two principals present. Commines also states that the bishop produced written evidence and witness depositions to prove his contention.

Nothing is documented to show Stillington appeared before the council on this day. If he had, and revealed such shocking news, wouldn’t it have leaked? Wouldn’t London have been agog? Wouldn’t someone have mentioned it in a letter or a chronicle?

On June 22nd, at the public pulpit outside St. Paul’s Cathedral, Dr. Ralph Shaa, along with other preachers in diverse places, revealed the sordid machinations of Richard of Gloucester’s brother and called for the disinheriting of his children. Leaving no stone unturned, they also repeated the old story about Edward himself being a bastard, which wasn’t a very nice thing to say about his mother who was still alive. Nothing was said on this occasion about Lady Eleanor or Stillington.

On June 24th the claim was repeated before the mayor and aldermen and the following day to an assembly of lords and clerics. (Parliament had been summoned for June 26th but then had been cancelled by writ. Some of the members had already arrived in London and some were on their way and decided to continue and stay on. Some had arrived for the coronation. This random group in no way constituted a parliament). On these occasions the scurrilous accusations about the Duchess of York had been dropped, never to be revived. Neither Eleanor Talbot nor Bishop Stillington were mentioned.

Nevertheless, it was this body that declared Edward V deposed and Richard of Gloucester the true claimant. Many of them accompanied Buckingham to Baynard’s Castle, along with the mayor and aldermen and some of the chief citizens, all eager to curry favor with the one in power and anxious to avoid the fate that had befallen Hastings only twelve days earlier. Richard, offered the crown, modestly declined the honor, and only accepted when Buckingham declared if he refused they would have to seek their king elsewhere.

In January of 1484, when the young sons of Edward IV had not been seen for several months, the first and only parliament of Richard III’s reign was held. A petition was presented called Titulus Regius, in which the king that laid out his justification for the seizure of his nephew’s throne. Fully six months after the coronation, during which time he and his advisers had had ample opportunity to do a thorough investigation and prepare their evidence. They had come up with five specious reasons, the precontract being the last. On this occasion a name was given to the poor lady Edward IV had allegedly deceived and debauched: Lady Eleanor Talbot. But no mention was made of Bishop Stillington; no evidence was presented. How distinctly odd!

My conclusion is that Stillington was a bit player, on the sidelines until he stepped forth in parliament and presented the petition, Titulus Regius. Yes, that much he did. And perhaps that’s why Philippe de Commines associated him with the precontract. Perhaps Titulus Regius is the written document to which Commines refers.

So, when next you read that Stillington’s evidence did not survive, I ask you to remember this: there never was any!

Other sources:

Dominic Mancini

The Croyland Chronicle

Charles Ross: Richard III

Wikipedia

July 4, 2015

This Sun of York

Here is the first installment of my second book. It describes the beginnings of the War of the Roses. Available on Amazon. http://www.amazon.com/Susan-Appleyard/e/B00UTVMT5Y

July 2, 2015

New book

My latest book is finished. Yay! Celebratory glass of wine. Many people have written books about the fascinating Eleanor of Aquitaine, but my book focuses on her equally fascinating husband Henry II, his quarrels with Thomas Becket, his sons and his wife. It’s tentatively called The Angevin. I won’t be publishing it yet though because I’ve already published three books this year and I have to begin my next book from scratch. Since it will be some months before it’s finished, Henry can fill in the gap.

June 27, 2015

View excerpts.

Once a week I shall be posting a few pages of my books. Click on the links above or the cover pages below to view an excerpt.

The books are available at: http://www.amazon.com/Susan-Appleyard/e/B00UTVMT5Y

June 24, 2015

The sad demise of Roger the Raker, a true story. (Ugh factor 10/10)

In London in days of yore disposing of sewerage was a serious problem. Some civic-minded citizens built latrines in their backyards. Roger was one of these. It consisted of a pit in the ground, four walls, a roof and door, with a wooden seat built over the hole. It was a luxury. Alas, in time the pit filled up, rotting the floorboards of the latrine. One day when Roger was sat there, contemplating the meaning of life, the floor gave way pitching him into the pit. Before help could arrive poor Roger drowned in a morass of human bodily waste.

June 22, 2015

Morton’s fork

This was the first one I came across that had an element of history in it. Let me begin by explaining Morton’s fork. Sir John Morton was a churchman who lived in the fifteenth century. He served under four kings and managed to make himself useful to all. His last king was Henry VII, who has come down to us with a reputation for parsimony and greed. Morton was his Archbishop of Canterbury and also became a cardinal – a truly godly man (a bit of irony there). When it came to squeezing taxes out of the people Morton developed this ruthless strategy: If the subject is seen to live frugally, tell him because he is clearly a money saver of great ability, he can afford to give generously to the King. If, however, the subject lives a life of great extravagance, tell him he, too, can afford to give largely, the proof of his opulence being evident in his expenditure. In other words, you poor suckers can’t win, so shut up and pay up.

Which brings me to the prompt.Morton’s Fork//

If you had to choose between being able to write a blog (but not read others’) and being able to read others’ blogs (but not write your own), which would you pick? Why?

Easy enough to answer, which is why I spun it out with the foregoing. I would choose to read others’ blogs and not write my own. The reason is that when I am writing my own blogs I already know what it is I’m writing about and the only thing I get out of it is (maybe) a few plaudits. When I read the blogs of others what I get is entertainment, information and sometimes a giggle. I hardly ever laugh at my own jokes.