Susan Appleyard's Blog, page 20

December 10, 2015

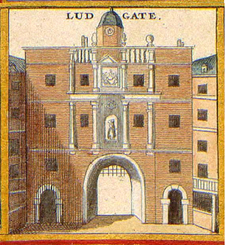

Ludgate Gaol

I should think most people’s idea about what a fifteenth century jail was like would be of a damp, dark, cold dungeon. A few wisps of foul straw on the floor. Perhaps a barred window high up. Desperate messages scratched on the walls, or written in blood. An iron door that clanged like the sound of doom when shut on the poor, ragged, half starved inmates. If you were writing a novel and you wanted the maximum drama, that’s the kind of prison your hero would find himself in, right?

Certainly not in Ludgate Gaol.

Ludgate prison

Ludgate prisonLudgate stood partly in Farringdon Ward Within and Farringdon Ward Without. The prison was built in 1378 in the gatehouse, the westernmost gate in London’s walls. It was intended as a prison for Freemen of the city and citizens convicted of non-felonious crimes, and for clergy who were imprisoned for minor offences. As such it was something of a holiday camp. Prisoners elected the warden and essentially ran the prison.

So comfortable was Ludgate that some of the prisoners made no attempt to pay off their debts and leave. This wouldn’t do at all, so in 1419 they were transferred to the much less salubrious Newgate Gaol where they were obliged to mix with a lower class of criminal. This didn’t work though, because Newgate was so overcrowded and unhealthy. Back they went to Ludgate.

A man name Stephen Forster had spent some time in Ludgate for debt. Obviously he was released and flourished because later he was knighted and became Lord Mayor. Circa 1450 Sir Stephen rebuilt the debtor’s prison larger and with a chapel and abolished the practice of making the debtors pay for their own food and lodgings.

The prison was rebuilt in 1586 and again after being destroyed in the great fire, finally closing in the nineteenth century.

Sources:

Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

Wikipedia

December 2, 2015

Another who should have been king.

Actually, he was a king. Unlike the unfortunate Edward V, he was not counted in the numerical succession of England’s kings because he was crowned in his father’s lifetime and never actually ruled. I refer to the man known as Henry, the Young King.

Henry, the Young King

Henry, the Young KingHenry was born on 28th February 1155, to august parents: King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He married Marguerite of France, daughter of King Louis VII and his second wife, Constance of Castile. The bride was two years old. The groom had attained the ripe old age of five.

According to W.L. Warren, ‘he was gracious, benign, affable, courteous, the soul of liberality and generosity. Unfortunately he was also shallow, vain, careless, high-hoped, incompetent, improvident, and irresponsible.’

Coronation of Henry the Younger

Coronation of Henry the YoungerOn 14th June 1170, for political reasons, he was crowned as an associate or junior king. He was not particularly interested in the business of government, preferring to spend his time in tournaments, at which he excelled. But he did want power, as did his younger brothers, Richard, who became Duke of Aquitaine and Geoffrey who became Duke of Brittany. Henry, whose patrimony would be England, Normandy and Anjou had no lands to rule because his father already ruled them. Henry the elder wasn’t about to hand over any part of his empire to a boy he he wouldn’t have trusted to oversee his kennels.

The two younger princes weren’t happy with their lot either. They complained their father kept them on a leading rein. In 1173, when Young Henry was eighteen, Richard fifteen and Geoffrey fourteen, their dissatisfaction came to a head. Louis of France stirred the pot. Add a handful of rebellious barons from most of King Henry’s domains, a couple of ripe ingredients like King William of Scotland and Queen Eleanor herself, and pretty soon the pot bubbled over into war. Sons against their father.

King Henry squashed that lot and forgave his sons and most of those who had rebelled against him. But he never forgave his wife. She remained captive for the rest of his life. Nor were the sons chastened. The only time Old Henry got any peace from their war-mongering was when they made war on each other.

1183 found the Young King in Limoges among some of his brother Richard’s most discontented barons. When Henry II tried to enter he was met by a shower of arrows, one of which pierced his cloak. Though Geoffrey came to the aid of his eldest brother, Young Henry was eventually forced to retire from Limoges – after robbing the townsfolk and plundering the shrine of St. Martial. When he later tried to return, the citizens threw stones at him. He wandered through southern Aquitaine, plundering shrines to pay his mercenaries, but with no particular military purpose.

At Martel he fell ill with dysentery and a fever and died on 11th June 1183. His father had been told of his illness and his pleas for forgiveness but, fearing another trick, he did not respond.

Three years later, Geoffrey was killed in a tournament. Richard, known as the Lionheart, became king after Henry II’s death.

Drawing from the recumbent statue in Rouen Cathedral.

Drawing from the recumbent statue in Rouen Cathedral.Young Henry was buried in Rouen. Judging from his conduct toward father and siblings, his death spared England another king the like of Stephen or John.

Sources:

Wikipedia,

W.L Warren: Henry II

November 21, 2015

The White Ship

King Henry I

King Henry IIn 1120 King Henry I had occupied the throne of England for twenty years. In that time he had sired many sons and daughters, but only two were legitimate. His daughter Matilda was married to the German Emperor. His son, William Adelin (or athelin) was his heir. A year earlier William had married Count Fulk V of Anjou’s daughter.

In November of that year, King Henry was about to cross from Normandy to England from the port of Barfleur. When the winds were right a man named Thomas FitzStephen approached and offered the use of a new vessel, named The White Ship. King Henry already had a fine ship for his own crossing, but suggested his son travel in the new vessel. William went aboard with two of his half-siblings and some two hundred and fifty others, many young people.

Aboard their own vessel and far from the stern eye of King Henry, the young people began to partay! Wine was also supplied to the crew on William’s orders. The revelers demanded that the captain overtake the king’s ship, which had already set sail. The white ship didn’t leave until after dark. It did not clear the harbor before striking a submerged rock and sinking. William Adelin managed to get into a small boat and might have survived, but he turned back upon hearing his half-sister’s cried for help. The boat he was in was swamped by those trying to get in and save their own lives. William drowned with the rest.

The White Ship sinking

The White Ship sinking

According to Orderic Vitalis only two survived by clinging to the rock all night. It was also reported that when he learned the heir of England had not survived, Thomas FitzStephen allowed himself to drown. (I wonder who found the courage to tell King Henry.)

More than the three hundred or so souls aboard died because of the wreck of the White Ship. With the loss of his heir, Henry tried to force the barons of England to accept his daughter Matilda as their queen. They were willing to swear an oath to her while the old king lived, but once he had departed for the next world, they supported Stephen of Blois’ bid for the throne. So began the civil war known as The Anarchy that lasted for nineteen years and heralded the advent of the Plantagenet dynasty.

The historian, William of Malmsbury wrote: ‘No ship ever brought so much misery to England.’

November 15, 2015

Almost king – Eustace of Boulogne –

Born c. 1129, Eustace Count of Boulogne was the son of Stephen of Blois and Matilda of Boulogne. Upon the death of King Henry I, Stephen seized the throne and fought a long civil war against Matilda, the only legitimate heir of the old king. Eustace married Constance, sister of Louis VII, making him, for a brief time, brother-by-marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Stephen of Blois

Stephen of BloisHe did little else in his life but fight and extort. He was not very popular. The Peterborough Chronicler tells us: He was an evil man and did more harm than good wherever he went.

In 1452, Stephen tried to persuade the barons to pay homage to Eustace as their future king, but the Archbishop of Canterbury and other bishops stated they would crown none but Henry of Anjou, eldest son of Matilda, The pope also supported the claim of Henry over Eustace.

Perhaps Eustace felt a grudge against the church, for the following year found him plundering the church of Bury St. Edmunds. Less than a month later he was struck down, as it was said, by the Hand of God.

After the loss of his heir, coming so soon after the death of his wife, (she had died the previous year) Stephen lost heart for the fight, and made an agreement with Henry of Anjou that he would remain king for his lifetime and Henry would succeed him.

It is likely the civil war would have continued as long as Eustace continued in life. His death grieved none but his father and opened the way for the far more capable Henry II to inherit the throne peacefully.

Eustace was buried at Faversham Abbey in Kent, alongside his parents. The tombs are now lost.

November 7, 2015

Rosamunde de Clifford, the most neglected royal courtesan.

Waiting for Henry

Waiting for HenryRosamunde de Clifford was the celebrated mistress of Henry II. She is believed to have been one of six children of the marcher lord Walter de Clifford and his wife Margaret. Rosamunde grew up at Clifford Castle, near Hay-on-Wye in the Wye Valley of Herefordshire, before going to Godstow Nunnery, near Oxford, to be educated by the nuns. At some point Henry and the fair Rosamunde met, possibly after his Welsh campaign in 1165 when he was looking into the security of the castles of the marches. He may have stopped at Clifford Castle for the night.

Clifford Castle ruins

Clifford Castle ruinsUndoubtedly Rosamunde became the love of his life, though it is unlikely he was any more faithful to her than he was to Queen Eleanor.

Many fables have grown around the love affair, for instance that Queen Eleanor poisoned her rival. Highly unlikely, as Eleanor was her husband’s prisoner from 1173 until his death. One story recounts that Rosamunde was roasted between two fires, stabbed and left to bleed to death in a bath of scalding water. Thankfully untrue.

It is generally thought that Henry installed her in the royal hunting lodge at Woodstock, and built for her a pleasure garden with a labyrinth, where she lived quietly and out of the public eye. Whenever he was in England he visited her there. Or possibly he left her in the care of her family and stopped in occasionally to give her a good roll in the hay before continuing about his busy life. I like to think not, but who can say how far Sir Walter was prepared to go in order to procure royal favor.

It is possible that Rosamunde traveled with her lover, but if not she must have been the most neglected royal mistress in history, for during the years that the affair lasted Henry was more often to be found in his continental domains than in England. In 1174 after the Great War, Henry acknowledged her openly and she was often seen with him.

How and why the affair ended is a matter for speculation. It is possible that Rosamunde wished to do penance for her sinful life, but her death shortly after taking the veil at Godstow suggests that she was already mortally ill when she retired as resident royal mistress. Rosamund died, still a young woman, on July 6th.1176. Henry himself died on the same day thirteen years later.

The ruins of Godstow Abbey

The ruins of Godstow AbbeyShe was interred before the altar at Godstow. Henry and the Clifford family paid for the tomb and an endowment that would ensure the tomb was cared for. Two years after Henry’s death Bishop Hugh of Lincoln (later to become St. Hugh) visited the nunnery and noticed the tomb was still covered with a silken cloth and flowers. He ordered the removal of the body to the cemetery ‘that other women, warned by her example, may abstain from illicit and adulterous intercourse’. The tomb was destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII. As for that prolific fornicator and adulterer, Henry II, Bishop Hugh made no attempt to interfere with his earthly remains.

You can meet Rosamunde in many poems and books, also in my favorite historical film, The Lion in Winter.

Sources:

Wikipedia

Henry II by W.L.Warren

October 28, 2015

Sir Thomas Malory

Very little is known about this intriguing man. We can say with a fair degree of certainty that he lived in the fifteenth century and that he wrote a book called Le Morte D’Arthur, the first prose account in English of the first English king. In the epilogue of the book we are told that it was completed in the ninth year of the reign of Edward IV, which would be 1469/70. The book was revised and printed by William Caxton in 1485. One thing more can be said: he spent some time in prison. And that’s about it.

The rest is based on the research of George Lyman Kittridge, an American scholar who wrote ‘Who was Thomas Malory’ in 1897 and is generally accepted as the most likely identification of Malory and account of his life.

According to Kittridge, Mallory was born at Newbold Revell in Warwickshire circa 1416 to John Malory and Philippa Chetwynd. His father held land in Warwickshire, Leicestershire and Northamptonshire and was sheriff, M.P. and J.P. several times. Thomas had several sisters but no brothers. Nothing is known of his early years.

As a young man he served in France under the Earl of Warwick and supported Lancaster during the War of the Roses. He was knighted in ’42 and became the Member of Parliament for Warwickshire in ’45 and served on commissions. He married Elizabeth Walsh of Wanlip in Leicestershire. His life seemed set upon the predictable course of a country knight, but, inexplicably, in 1450 he turned to a life of crime. In January, with twenty-six others, he allegedly planned to ambush the Duke of Buckingham. In May, he allegedly raped Joan Smith at Coventry. The charge was brought by her husband under a statute of Richard II making the act of elopement into a crime of rape even when the woman consented. Also in May, he extorted money from two residents of Monks Kirby, then in August allegedly raped Joan Smith again and stole money from her husband. Again in August, he allegedly committed extortion against another man of Monks Kirby. Whew! No wonder Sir Thomas ended up in prison.

On March 5th 1451, a warrant was issued for his arrest, but the crime spree wasn’t over and he apparently stole cattle in Warwickshire. The Duke of Buckingham with sixty men tried to apprehend him, but meantime Malory raided the duke’s hunting lodge, killing deer and damaging the property.

Finally he was arrested at Coleshill, but escaped by swimming the moat. Next he raided Combe Abbey with a hundred men, insulted the monks and stole money. By January 1452 he was in prison in London, mostly in Newgate, where he spent most of the next eight years awaiting trial. He was bailed out several times, and at one point joined a horse-stealing expedition, which put him in prison in Colchester. After escaping again, he was recaptured and taken back to London.

Malory received a pardon from the Yorkists and aided Edward IV and the Earl of Warwick in the recovery from the Lancastrians of castles they held in Northumberland. But in 1468 he seems to have changed sides again because from then on he was excluded from royal pardons. By that time he was in prison again, completing Le Morte D’Arthur. He died in 1471 and was buried in Greyfriars in Newgate. Nothing remains of his grave.

What a colourful, criminal life Sir Thomas had. There are some who cannot reconcile this reprobate with the author of Le Morte D’Arthur and claim that it is a case of mistaken identity, that the author was a law-abiding Yorkshire knight. Others claim he was a Welshman.

Would the real Sir Thomas Malory please stand up.

October 21, 2015

Spotlighting Tony Riches

OWEN – Book One of The Tudor Trilogy, by Tony Riches

England 1422: Owen, a Welsh servant, waits in Windsor Castle to meet his new mistress, the beautiful and lonely Queen Catherine of Valois, widow of the warrior king, Henry V. Her infant son is crowned King of England and France, and while the country simmers on the brink of civil war, Owen becomes her protector.

They fall in love, risking Owen’s life and Queen Catherine’s reputation—but how do they found the dynasty which changes British history – the Tudors?

This is the first historical novel to fully explore the amazing life of Owen Tudor, grandfather of King Henry VII and the great-grandfather of King Henry VIII. Set against a background of the conflict between the Houses of Lancaster and York, which develops into what have become known as the Wars of the Roses, Owen’s story deserves to be told.

Available on Amazon UK and Amazon US

About the Author

Tony Riches is a full time author of best-selling fiction and non-fiction books. He lives by the sea in Pembrokeshire, West Wales with his wife and enjoys sea and river kayaking in his spare time.

For more information about Tony’s other books please visit his popular blog, The Writing Desk and his WordPress website and find him on Facebook and Twitter @tonyriches.

Table of links:

Item

Hyperlink

OWEN on Amazon UK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B011YBZU8U

OWEN on Amazon US

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B011YBZU8U

OWEN on Smashwords

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/562360

Book Trailer on YouTube

http://youtu.be/ELH4IU5pxds

The Writing Desk

http://tonyriches.blogspot.co.uk/

Author Website

http://tonyriches.wix.com/historical-fiction#!the-tudor-trilogy/c1sw2

OWEN on

WordPress

https://tonyrichesauthor.wordpress.com/2015/07/19/owen-book-one-of-the-tudor-trilogy/

Tony on Twitter

https://twitter.com/tonyriches

Tony on

Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/tonyriches.author

Tony on Google+

https://plus.google.com/+TonyRiches/posts

Amazon Author

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Tony-Riches/e/B006UZWOXA/

Goodreads

Author

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/5604088.Tony_Riches

October 9, 2015

Edward IV the captive king

In July 1469 King Edward, caught unaware, was taken captive by the Archbishop of York and conveyed to Warwick Castle. There the Earl of Warwick was awaiting him, along with the Duke of Clarence. By this time Edward would have known that his old friend and most powerful supporter had crossed his personal Rubicon and was in open rebellion, but it must have come as an unpleasant shock to learn that his brother had joined him. Clarence had recently married Warwick’s daughter Isabel in defiance of the king’s order.

Embracing the expedient, Edward and Warwick reached a tacit understanding from the first. Edward was the honoured guest and Warwick was the gracious host. No dungeon and chains for the king. In return for his smiling compliance he was rewarded with comfortable quarters, good food and wine, the run of the castle, and perrhaps a bedmate to keep him happy. This mutually satisfactory relationship must have been strained, at least on the king’s part, when he was taken to Gosforth Green and forced to watch the summary execution of his queen’s father and one of her younger brother’s, 21 year-old John. The three Herbert brothers had been previously executed without trial for no better reason than they were supporters of the king.

Warwick Castle

Warwick CastleNevertheless, Edward was prepared to do whatever was necessary to survive and gain his freedom. As for Warwick, he was probably the only man in history to hold two kings captive at the same time. Henry of Lancaster would remain in the Tower, but what was he planning to do with Edward of York? My own thought is that Warwick was not a long-range planner, but more impetuous than calculating. He was arrogant enough to believe that once he had obtained his goal, the future would always arrange itself in manner convenient for him. It is possible that he was planning to replace Edward with George of Clarence, but Edward could not be arbitrarily shoved aside to make room for his brother. That option would require Edward’s permanent. Warwick wasn’t prepared to go that far. The ostensible reason for his rebellion was to protect the king from the influence of evil councilors. Despite the unpopularity of the Woodvilles, only the Earl of Oxford joined him in the enterprise.

Edward was transferred to Middleham, Warwick’s great castle in Yorkshire, a safer distance from London and his friends. The countess and her two daughters were in residence, which must have occasioned some very uncomfortable dinners on their part.

Finally power was in Warwick’s hands. But within thirty days of his astonishing victory, the tide began to turn. As often happened during any disruption of central authority, London was in uproar. Sporadic violence broke out all over the country. In the north, Humphrey Neville, a kinsman of Warwick’s unfurled the banner of Lancaster. Whatever Warwick’s plan was, allowing Neville to resurrect the spectre of Lancaster wasn’t part of it. Not at this time. As it was necessary to wipe his recent activities clean of the taint of treason and give them the sanctity of law, he had the chancellor send out writs summoning parliament to meet at York. But parliament had to be postponed because the members were unlikely to give him the rubber stamp when it was clear he could not keep order in the land. Then he sent out a call to arms to help him put down the renegade Neville’s revolt and learned that the kingdom wouldn’t support him while he held the king captive. So he rode with the king from Middleham to York – Edward showing by his friendly demeanour that all was well between him and his mighty cousin. And suddenly Warwick had all the men he needed. Humphrey was speedily dealt with.

Perhaps at this time, Warwick began to suspect that his rebellion wasn’t going to have whatever end he had envisaged. That suspicion was confirmed when he was with the Edward at Pontefract and a bevy of loyal lords, including the Duke of Gloucester and Lord Hastings, arrived and convinced him that it was time to release the king. Benevolent as always, Edward assured his treasonous cousins and brother that there would be no repercussions. And there were none.

In October he returned to London to a grieving wife and a joyous welcome by the citizens.

September 29, 2015

Animals on Trial

In 1457 in the village of Sauvigny, France, a sow and six piglets were accused of killing a five year-old boy. The animals were put on trial – a trial complete with judge, two prosecutors, eight witnesses and a defense attorney. Witnesses testified that the sow had indeed killed the boy. The piglets on the other hand were not seen taking part in the attack. Consequently, the sow was hanged. The judge found the piglets not guilty, not only because no witnesses implicated them, but also because they were immature and. due to the corrupting influence of their mother, were unable to make reasoned choices. They were remanded into the custody of their owner.

This case was by no means unique. From at least the thirteenth century when the first case was recorded until the eighteenth, many animals were tried for crimes ranging from murder to criminal damage. Usually if convicted the animals would either be hanged or exiled. If tried in an ecclesiastical court the animal might be excommunicated.

In a court of law they were treated the same as humans. Judges took these cases very seriously and weighed the evidence and witness testimony carefully.

In 1750, a female donkey was charged with bestiality. Her human owner was sentenced to death, but the donkey was exonerated because witnesses testified in writing that she was “in word and deed and in all her habits of life a most honest creature.”

In 1474 a rooster was tried for the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg, which the townsfolk took to be a manifestation of Satan.

In a 1379 case a swine herder’s son was attacked by two herds of pigs. The court found that one herd was the instigator and the other had just joined in later. The judge sentenced both herds to death because he determined that their cries of enthrallment during the attack meant that they expressed approval of it.

In 1494 a pig wandered into a house where the parents were absent and ate the face and neck of a baby in its cradle. The judge declared that in order for an example to be made and justice maintained, the pig should be hanged on the common gibbet. Again in 1567, a sow was convicted not only for assaulting a 4-month-old girl, but for doing so with extreme cruelty. In 1314, a bull was hanged after it escaped from its pen and attacked a passerby,

The animals most commonly put on trial were pigs, bulls, horses, goats, cows, rats, and weevils. Some poor creatures suspected of being familiar spirits or engaging in bestiality were burned at the stake without benefit of trial.

(In the case of insects my imagination runs wild. Would they appear in court? A bunch of weevils in a glass jar perhaps? If found guilty would they be ‘exiled’ or stomped? How could the court be sure it wasn’t a case of mistaken identity?)

Today, if a human being was seriously hurt by an animal, whether wild or domestic, the animal would be euthanized. But why put animals on trial?

The phenomenon has been studied by scholars and a number of (sometimes esoteric) theories put forward. One theory is that “in a society of people who believed deeply in a divinely determined order of being, with humans at the top, any disruption of God’s hierarchy had to be visibly restored with a formal event.” I read that to mean an eye for an eye. Another hypothesis is that animal trials gave the authorities the opportunity to punish people for the behavior of their animals, particularly pigs that were often allowed to roam over common areas. Both of these theories do not take account of the fact that summary execution, rather than a costly and time-consuming trial, would have achieved the same result.

The only theory to answer that conundrum, and my particular favorite, is that our ancestors thought the animals among them worthy of justice because they had, like humans, the free will to make basic choices. This may sound like a weird conclusion at first. But the fact is that medieval literature is full of pictures of animals dressed in human clothing and engaged in human activities – even going to war. Our ancestors lived as closely with their domestic animals as we do with our pets, sometimes sharing their home with a valuable beast. It would not be so surprising if they ascribed human qualities to their animals as people today do to their pets. How else explain how a pig could be judged to have acted with ‘extreme cruelty’ or a donkey said to be ‘a most honest creature’?

I have to conclude with a quote from one of the websites I visited. “We condemn billions of animals to conditions that amount to torture without a trial.” And then execute them. Hmm.

New Release!

Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2

Edited by Debra Brown and Sue Millard.

To order Castles, Customs and Kings in the U.S., go to http://www.amazon.com/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817.

To order the book in the United Kingdom, go to http://www.amazon.co.uk/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817

This is a Blog Hop!

To link to the rest of the blogs please click below.

http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2015/09/crazy-customs-from-past-blog-hop-and.html

Animal Trials.

In 1457 in the village of Sauvigny, France, a sow and six piglets were accused of killing a five year-old boy. The animals were put on trial – a trial complete with judge, two prosecutors, eight witnesses and a defense attorney. Witnesses testified that the sow had indeed killed the boy. The piglets on the other hand were not seen taking part in the attack. Consequently, the sow was hanged. The judge found the piglets not guilty, not only because no witnesses implicated them, but also because they were immature and. due to the corrupting influence of their mother, were unable to make reasoned choices. They were remanded into the custody of their owner.

This case was by no means unique. From at least the thirteenth century when the first case was recorded until the eighteenth, many animals were tried for crimes ranging from murder to criminal damage. Usually if convicted the animals would either be hanged or exiled. If tried in an ecclesiastical court the animal might be excommunicated.

In a court of law they were treated the same as humans. Judges took these cases very seriously and weighed the evidence and witness testimony carefully.

In 1750, a female donkey was charged with bestiality. Her human owner was sentenced to death, but the donkey was exonerated because witnesses testified in writing that she was “in word and deed and in all her habits of life a most honest creature.”

In 1474 a rooster was tried for the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg, which the townsfolk took to be a manifestation of Satan.

In a 1379 case a swine herder’s son was attacked by two herds of pigs. The court found that one herd was the instigator and the other had just joined in later. The judge sentenced both herds to death because he determined that their cries of enthrallment during the attack meant that they expressed approval of it.

In 1494 a pig wandered into a house where the parents were absent and ate the face and neck of a baby in its cradle. The judge declared that in order for an example to be made and justice maintained, the pig should be hanged on the common gibbet. Again in 1567, a sow was convicted not only for assaulting a 4-month-old girl, but for doing so with extreme cruelty. In 1314, a bull was hanged after it escaped from its pen and attacked a passerby,

The animals most commonly put on trial were pigs, bulls, horses, goats, cows, rats, and weevils. Some poor creatures suspected of being familiar spirits or engaging in bestiality were burned at the stake without benefit of trial.

(In the case of insects my imagination runs wild. Would they appear in court? A bunch of weevils in a glass jar perhaps? If found guilty would they be ‘exiled’ or stomped? How could the court be sure it wasn’t a case of mistaken identity?)

Today, if a human being was seriously hurt by an animal, whether wild or domestic, the animal would be euthanized. But why put animals on trial?

The phenomenon has been studied by scholars and a number of (sometimes esoteric) theories put forward. One theory is that “in a society of people who believed deeply in a divinely determined order of being, with humans at the top, any disruption of God’s hierarchy had to be visibly restored with a formal event.” I read that to mean an eye for an eye. Another hypothesis is that animal trials gave the authorities the opportunity to punish people for the behavior of their animals, particularly pigs that were often allowed to roam over common areas. Both of these theories do not take account of the fact that summary execution, rather than a costly and time-consuming trial, would have achieved the same result.

The only theory to answer that conundrum, and my particular favorite, is that our ancestors thought the animals among them worthy of justice because they had, like humans, the free will to make basic choices. This may sound like a weird conclusion at first. But the fact is that medieval literature is full of pictures of animals dressed in human clothing and engaged in human activities – even going to war. Our ancestors lived as closely with their domestic animals as we do with our pets, sometimes sharing their home with a valuable beast. It would not be so surprising if they ascribed human qualities to their animals as people today do to their pets. How else explain how a pig could be judged to have acted with ‘extreme cruelty’ or a donkey said to be ‘a most honest creature’?

I have to conclude with a quote from one of the websites I visited. “We condemn billions of animals to conditions that amount to torture without a trial.” And then execute them. Hmm.

New Release!

Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2

Edited by Debra Brown and Sue Millard.

To order Castles, Customs and Kings in the U.S., go to Amazon US http://www.amazon.com/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817.

To order the book in the United Kingdom, go to http://www.amazon.co.uk/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817 This is a Blog Hop!

To link to the rest of the blogs please click below.

http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2015/09/crazy-customs-from-past-blog-hop-and.html