Susan Appleyard's Blog, page 11

July 12, 2018

In Spite of Lions by Scarlette Pike

Set in 19th century London & Africa

Anna is running away. From whom or what? She has changed her name and takes passage on a ship bound for anywhere. She doesn’t care, doesn’t even want to know. She is determined to shed the constraints of her society and live independently somewhere far away from England. The captain of the ship turns out to be a man from her past, the husband of a late and dear friend. He too has changed his name. Why? He is a very menacing and mysterious character and Anna is wary of him. Could he possibly be the love interest? To add a little more spice to the pot, also on the ship are Mrs David Livingstone and children who are going to meet Mr Livingstone. Yes, Anna’s destination turns out to be Africa.

By this time – the third chapter – I was so firmly hooked, I could hardly move.

Nothing could be a greater contrast to Anna’s previous experience than the lifestyle of the Livingstones and the culture of Africa. We observe this young, well-bred English lady as she rides for days in the back of a wagon, watches an animal being butchered, learns to pluck a fowl, lives through a drought, a lion attack and a war… and yet loves Africa. Meanwhile, she suffers nightmares of her past life and struggles to come to terms with the person she was.

Anna is a bit of a trope – a woman trying to live according to the mores of a later time – but because of the author’s excellent writing and story-telling, she rises above such clichés. All the main characters are interesting and well-presented, but my favourite is the Chief – also a real person – as colourful and delightful a character as you could hope to meet. The relationship between him and the Livingstones is heartwarming.

Judging by the ending, I feel sure there will be another book.

Heartily recommended

*****

I wrote this review for Discovering Diamonds

June 28, 2018

A Woman’s Lot by Carolyn Hughes

Set in 14th century, rural England, this is the second book of the Meonbridge Chronicles. Like the first it’s set in fictitious Meonbridge, a few years after the Black Death passed through Europe, wiping out large segments of populations and leaving rural England with a shortage of labour. You would think that at such a time women might be employed to fill the gaps, but according to this book that was not the case.

There are several protagonists, all women. They are married with children, with the exception of Eleanor. They are ambitious to improve their ‘lot’ but are stumped by their men. Agnes wants to do woodwork, but her husband holds her back. Henry Miller doesn’t even want his wife to set foot in the mill. Eleanor is looked on with suspicion because she has the audacity to own a flock of sheep without a husband to control her. Attitudes are polarised, particularly among the men when a woman is tried for bashing her husband with a cooking pot. She is subjected to the ordeal, banned a century earlier (as the author notes) and survives. The women aren’t sympathetic because she is a scold. But when another woman is accused of murdering her husband, admittedly on little evidence, they are caring and supportive. In a similar vein, there is a sheep-stealing incident at the beginning of the book. One of the perpetrators is 21 years-old and viewed as a troublemaker, the other an 11 year-old who is ‘simple’ and easily led. The village is sympathetic to one but not the other, who is subjected to the full rigours of the law: loss of a hand.

The charm of this book lies in the characters. They are so ordinary, and I mean that in the best possible way. They are your neighbours, your friends, facing very different circumstances, of course. There are the good and the bad. They gossip about each other and support each other. They have their dreams, frustrations, disappointments, prejudices, joys and sorrows just as we do. They face the challenges life throws at them with varying degrees of success.

I have one little grumble. I realise the author was trying to maintain the ‘voice’ of the characters throughout the narrative, but I found the use of the contraction ‘d, as in Ralph’d said, instead of had or even would, a little irritating. Also, the phrase ‘so many fewer’ jarred me. It is an oxymoron

That apart, the book is a thoroughly enjoyable slice of 14th century life, and I hope there are many more tales to be told of the folks of Meonbridge.

****

June 14, 2018

Cover reveal

Most of my previous books have dealt with tragedies and I have killed off a lot of characters in various ways. This might lead my readers to think I am either a very dark and gloomy person or a closet psychopath. Neither is the case, I assure you. And to prove it I have written a light-hearted historical romance set in the fifteenth century during the War of the Roses. Here is the cover for it which I am quite pleased with. The book itself is coming soon to a theatre retailer near you.

[image error]

See more of my books at Smashwords: https://www.smashwords.com/books/search?query=Susan+Appleyard

Or visit my author page at Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Susan-Appleyard/e/B00UTVMT5Y

June 7, 2018

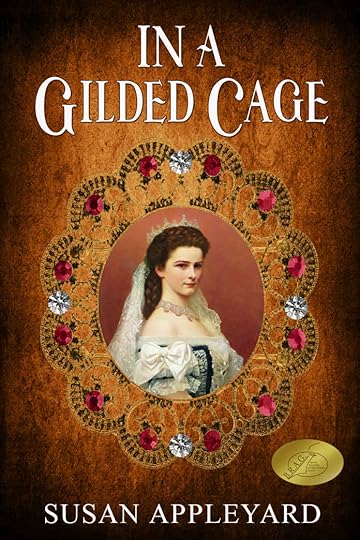

In a Gilded Cage

A wonderful in-depth and insightful review by Linda Root.

Coronation photo by Emil Raberding., Creative Commons

I first met Elisabeth, Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary, in the pages of Susan Appleyard’s biographical novel, In a Gilded Cage, when the novel was among the semi-final entries in the M.m. Bennetts Award competition in 2016. The three board members on the panel of readers had committed to read each of the more than forty entries, an ambitious project which did not allow time for a critical analysis of each and every book. There were few biographical historical novels in the running The three that come to mind in addition to Gilded Cage are Janet Wertman’s Jane the Quene, Grace Tiffany’s Gunpowder Percy, and Mark Beauregard’s, The Whale ~A Love Story. I am a historical novelist writing in Tudor and Stuart Britain, so I was well within my comfort zone reading the novels featuring Jane Seymour and Thomas Percy. Nor was I a stranger to Melville and his association with Nathaniel Hawthorne. whose masterworks I read in high school. Of the protagonists involved, I was the least familiar with Elisabeth of Austria, best known to late nineteenth century history buffs as Sisi, whom I vaguely recollected as the subject of a series of German language films starring a very youthful Romy Schneider, which were re-released about ten years ago with subtitles I found tedious and put aside. Until I encountered Susan Appleyard’s fine book, while I remembered Sisi as a legendary beauty, I was totally unaware of the role she played in shaping late Nineteenth Century European history. Thanks to Ms. Appleyard’s gift for breathing life into her characters, I feel as if I know Sisi well.

The complete story of Empress Elisabeth is much longer than the portion featured in Susan Appleyard’s novel, and in retrospect, I suspect I know the reason: I experienced a single event in my own professional life when I said to myself ‘if my life were to end here and now, I would die knowing I had achieved the goal I sought.’ Likewise, if there was a single moment in Sisi’s life when she might have shared the sentiment, it was when she stood beside her sometimes autocratic but loving husband Emperor Franz Josef, with her intimate friend and confidante Count Gyula Andrassy nearby, and was proclaimed Queen of Hungary, the country she so deeply loved. The ceremony culminated in a diplomatic bloodless coup joining Austria and Hungary in a union increasing Hungary’s status in the Empire, and it had been engineered by the Empress and Andrassy. In a brave display of artistic sensitivity, Ms. Appleyard chooses to end her novel there. The rest of it, the sadness, the tragedy of Mayerling, the scandals, deaths and the assassination, can be found in Wikipedia and in the videos and movies. No honest telling of Elisabeth of Austria’s life story would be a happy one, but Gilded Cage ends on a triumphant note, and in that sense, it is unique.

Hungarian Coronation with Andrassiy doffing his cap, from news clipping

SOME THOUGHTS ON THE CHALLENGES OF HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHICAL NOVELS:

There are limitations in dealing with biographical novels that makes them difficult to review. Spoilers are unavoidable. We all know Anne Boleyn died on Tower Green, likely hoping for a reprieve that did not come. Whoever may have fired the fatal shot, JFK did not survive the bullet. It is easier to deal with relatively obscure historical characters who lived long ago, because little in the way of a written record survives. Such is not the case in dealing with a character like Elizabeth Tudor, who was sovereign of an especially literate society for the day, and a mistress of the written word. For her, obscurity was not an option. The same is true when it comes to Elisabeth, Empress of Bavaria and Queen of Hungary. She was thought to be the most beautiful woman in the world at a time when photography was in vogue. She considered chronological age an enemy and did not sit for any portrait after she reached thirty, but she could not evade the cameras. She leaves galleries of visual imagery but she also leaves a catalog of faults. What I find outstanding in Gilded Cage is the means whereby the author achieves a balance between what is speculative and what is known. It is, for example, one thing to describe a woman famous for her 18-inch waist and quite another to recreate what it felt like to be laced into the double corsets required to achieve it. Likewise, there is much to be told in the widely circulated public family portrait of the Habsburgs, shown below, but much more poignantly in Appleyard’s accounts of Sisi rushing to her children’s nursery to be turned away because she had not acquired her mother-in-law’s permission to visit.

There are limitations in dealing with biographical novels that makes them difficult to review. Spoilers are unavoidable. We all know Anne Boleyn died on Tower Green, likely hoping for a reprieve that did not come. Whoever may have fired the fatal shot, JFK did not survive the bullet. It is easier to deal with relatively obscure historical characters who lived long ago, because little in the way of a written record survives. Such is not the case in dealing with a character like Elizabeth Tudor, who was sovereign of an especially literate society for the day, and a mistress of the written word. For her, obscurity was not an option. The same is true when it comes to Elisabeth, Empress of Bavaria and Queen of Hungary. She was thought to be the most beautiful woman in the world at a time when photography was in vogue. She considered chronological age an enemy and did not sit for any portrait after she reached thirty, but she could not evade the cameras. She leaves galleries of visual imagery but she also leaves a catalog of faults. What I find outstanding in Gilded Cage is the means whereby the author achieves a balance between what is speculative and what is known. It is, for example, one thing to describe a woman famous for her 18-inch waist and quite another to recreate what it felt like to be laced into the double corsets required to achieve it. Likewise, there is much to be told in the widely circulated public family portrait of the Habsburgs, shown below, but much more poignantly in Appleyard’s accounts of Sisi rushing to her children’s nursery to be turned away because she had not acquired her mother-in-law’s permission to visit.

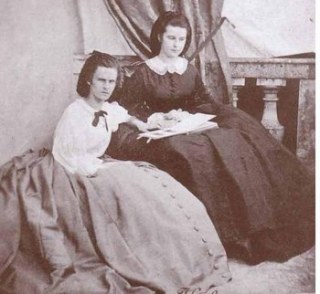

Franz Josef at the left, Sisi seated with her children, Sophia center foreground,

the Emperor’ father Archduke Franz Karl in the stove-pipe hat.

DESPITE A HANDSOME PRINCE, AN UNLIKELY BRIDE, AND AN ELEGANT BALL, GILDED CAGE IS NOT A CINDERELLA STORY:

In the firsts pages of Susan Appleyard’s novel, the reader is presented with a familiar theme, one worthy of a Disney classic: the most powerful and handsome sovereign in Christendom is about to stage a ball to which the eligible royal beauties of Europe and their families will be invited. The Habsburg Emperor of Austria is shopping for a bride, and the Bavarian princesses of the house of Wittelsbach are in the running: And thus, the story begins.

Helene (Nene) and Elisabeth (Sisi)

Their mother Princess Ludovica, is one of nine daughters of the King of Bavaria, and although she had made a less than stellar marriage than her other sisters, she is very interested in the welfare of her daughters. Much of the family finances will be diverted to dressing them for their trip to the Austrian summer palace to attend the ball. To add to the tension, her older sister Sophie, mother of the Emperor, is coming to their relatively modest home for a visit, no doubt to make certain her less exalted relatives are suitably attired and disciplined, so as not to be an embarrassment. She is delighted with the older sister, known in to the family as Nene, and in her mind’s eye, she has placed the mythical glass slipper on Nene’s foot, but she finds the younger sister Sisi’s lack of refinement appalling. Sisi is a hoyden.

Young Franz Josef, Wikimedia Commons

While Aunt Sophie is making her presence felt at her sister’s home, her son the Emperor Franz Josef and his younger brother make a surprise visit to his Bavarian cousins. At this point, a reader does not need to know Austro-Hungarian history to guess what happens next.

All of the ingredients of a Cinderella story are in Appleyard’s novel. While there is no evil step-mother, there is indeed a mean-spirited mother-in-law, and the prince is sufficiently regal and utterly handsome, but a divine right monarch out of touch with the times. He is also under his mother’s thumb.

The major conflict in the novelization of Sisi’s life is the well-documented tension between Sisi and her mother-in-law, her maternal aunt Archduchess Sophie, which the author conveys to her readers in well-constructed scenes. The narrative is never overwhelming. For example, Franz Josef makes his feelings for Sisi obvious by giving her a nosegay of white flowers symbolic of a declaration of betrothal. However, his courtly gesture is unknown to his fifteen year old Bavarian cousin, who has to be told by her companions what the gesture means. The novel is filled with similar scenes.

Since Sisi was not the Archduchess’s choice of wife for her doted-upon son, the Archduchess was delighted when Sisi herself asked to delay a formal betrothal until she was sixteen. Thereafter, Sophie’s fault finding of her niece became relentless, but not in Franz Josef’s presence. There is little his mother can do to change his mind without overplaying her hand. Nevertheless, the battle lines are drawn. And because Archduchess Sophie was no fool, her enemy was never Franz Josef, but the not-yet-sixteen year old prospective bride with neither the training nor the desire to become a Habsburg Empress, nor the expertise to deal with a venomous prospective mother-in-law. The Archduchess took advantage of her son’s fiancee’s youth and naivete, and criticized her mercilessly, but when Franz Josef’s infatuation did not fade, the wedding proceeded as planned. As appropriate to the groom’s station, it was held in Vienna, on April 24th , 1854, in the presence of the Viennese court and a thousand assorted guests. As soon as the vows were spoken, Elisabeth’s Bavarian waiting-ladies were sent home. The ensuing struggle is the major theme of the first half of the novel, and leaves no clear winner.

Wikimedia Commons

While Franz Joseph was deeply in love with his wife, he was also cowed by his formidable mother. He had been under this mother’s tutelage and control since birth. One thinks of Catherine d’ Medici’s gift for exerting power over her sons.

Kaiserin of Austria 1862, a young Sisi

The theme of the first half of the book focuses on the disaster that ensues when Sisi moves to Vienna and finds she truly is a pretty bird in a gilded cage. A telling scene in the novel occurs at a meeting in which she and Archduchess Sophie were present with the men, but at which Sisi was expected to remain silent while Sophie presided on behalf of her son. When Sisi cleared her throat and suggested a less bellicose approach to relations with their Hungarian satellite nation, the others gasped and, Sophie stomped out of the room. On such occasions, Franz was indulgent of his pretty wife but almost always sided with his mother. One topic upon which he and his mother always agreed was the need to take a firm hand with the Hungarians. Thus, the Hungarian dilemma becomes central to the plot and moves the novel into its second phase, when Sisi, although miserable, learns to assert herself in subtle ways in which her beauty is her weapon.

Sisi, 1855

From research accompanying my initial reading during the MmBA Competition more than a year ago, the story related in the pages of A Gilded Cage is substantially accurate and artfully told. The dialog presented is believeable and appropriate to the era. Sisi had not been groomed to the life of an Austrian empress. Even as she matured, she was never acclimated to the adulation of the crowds she drew. She ceased having marital relations with her husband, who was still in love with her, and she often fled to the satellite nation of Hungary, where she enjoyed a better climate, both weather-wise and in terms of her personal popularity. She was always in better health when she was away from her mother-in-law and Austria. She loved Hungary and its people reciprocated. There are shallow aspects to her character, especially centering on her obsession with the circumference of her waist (never more than 18 inches except when pregnant), control of her weight at less than 1000 lbs, and the length and grooming of her hair. In spite of the commotion her appearances created, she was afraid of crowds. From Ms. Appleyard’s accounts, one might surmise she preferred the company of horses.

Gyula Andrassy, Public Domain art

A notable feature of the novel is the depth of the author’s treatment of lesser characters, for example in a vignette in which Sisi’s attendant Ida, who was a supporter of the Hungarian cause and was about to be dismissed, could not be made a lady in waiting to the Empress because she lacked the pedigree. But Sisi, who by that time was beginning to wield some degree of power over her circumstances, made her an adviser instead, which made her immune to arbitrary dismissal. Appleyard also cleverly introduces Sisi to the character of Gyula Andrassy through Ida’s recounting of his heroism and his charm. Thus, the stage is set for their meeting, which does not occur until the last portion of the novel.

While they play a small part in the story, Sisi’s parents are well drawn characters, as are her siblings. Much of the history of the times is told in thumnail sketches featuring Sisi’s siblings and her Habsburg inlaws. The novel has a large cast of minor characters, but features Sophie as the antagonist, and the Count as Sisi’s elusive romantic interest.

THE BACKSTORY:

The second half of Appleyard’s arresting novel focuses on the manner in which a woman of no special intellectual gifts or training drew a kingdom of forward looking rebellious but pragmatic Hungarians into accepting a limited monarchy rather than resorting to another failed rebellion, and at the same time, seduced her quasi-estranged autocratic husband into going along with the plan. Her weapon was her beauty and the fact Franz Josef never stopped loving her. But beauty also was her curse. A young woman heralded as one of the most beautiful woman in the world is bound to have enemies, and she was not a good fit at the formal Viennese court.

The second half of Appleyard’s arresting novel focuses on the manner in which a woman of no special intellectual gifts or training drew a kingdom of forward looking rebellious but pragmatic Hungarians into accepting a limited monarchy rather than resorting to another failed rebellion, and at the same time, seduced her quasi-estranged autocratic husband into going along with the plan. Her weapon was her beauty and the fact Franz Josef never stopped loving her. But beauty also was her curse. A young woman heralded as one of the most beautiful woman in the world is bound to have enemies, and she was not a good fit at the formal Viennese court.

In documenting how she deals with conflict, Appleyard is sympathetic to Sisi, but she does not paint her free of flaws. Nor does she make the Empress of Austria into a super hero, a model wife and mother, or a warrior queen, although she has some characteristics of each. To the author’s credit, she does not attempt to resolve the issues that make Sisi enigmatic. The extent to which her physical ailments are psychologically based, and more important, the nature of her relationship with the Hungarian patriot and statesman Gyula Andrassy remain unresolved. In the final scene between them just before her coronation, he asks permission to kiss her hand, and the manner in which he strips away her glove is an sensual as any scene I have read. The ensuing kiss lingers too long to be proprietous and is as close as the author brings them to open acknowledgment of a love affair, as they go their separate ways, never together and never apart, bound by their affection for one another and their hope for Hungary.

Andrassy, as Austrian foreign minister, with von Bismark the Berlin Conference of 1878

In Susan Appleyard’s novel, the political changes affecting late Nineteenth Century Europe are always in the background and dominate the last third of the book. The political climate of the final pages elevates the novel from the crowded shelf of many fine books about tragic queens, and places it among novels of political historical value. For all of his charm and Hungarian panache, Andrassy, as the author presents him, is the personification of change. He became a major statesman in the last years of the 19th Century, and made policies that endured until the end of WWI.

Thus, In a Gilded Cage is not just Sisi’s story, but an account of the early stages of the fall of the Hapsburg empire, reflected not only in the life of the Empress, but in the lives of her siblings and her cousins –minor characters in the novel, but major players on the world stage. Through a series of artfully presented family vignettes, the reader becomes acutely aware that Sisi and Franz Josef’s world is crumbling. From Mexico to the Baltic, the Habsburg sun is setting. In persuading her husband to adopt a dualist Austro-Hungarian government that avoided bloodshed, Sisi bought the Habsburgs a little more time in the sun. I doubt I would feel the impact of the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as strongly if I were reading a traditional history.

CONCLUSION:

As I read In a Gilded Cage the first time, and even more so as I review it now, I cannot help equating Sisi with Diana, two young women of good looks and impressive pedigree who nevertheless were thrust onto the world stage in roles they were never meant to play, and who, all things considered, managed to capture the hearts of the common folk in a way no one could have predicted. And while a happy life may have eluded both Elisabeth of Austria and Diana, Princess of Wales, neither faded into obscurity, and each brought a bit of luster and legitimacy back into the faltering concept of monarchy. I highly recommend this book to anyone who enjoys history framed as art.

May 28, 2018

Who’s Pointing At You?

David Gaughran’s views are always informative and delivered with a dose of humour.

The Also Boughts on your page are an important indication of what readers are buying along with your books.

The Also Boughts on your page are an important indication of what readers are buying along with your books.

But those particular Also Boughts are only part of the story. What’s really important is which books are pointing back at you.

Let’s use my long-suffering book Liberty Boy as an example again.

As I explained yesterday’s post – Please Don’t Buy My Book – Liberty Boy was dragged down into the ranking depths after having no Also Boughts for months thanks to an Amazon snafu. I eventually fixed that problem in a fairly crude way by running a 99c Countdown and throwing whatever ads I could get at it.

The promo itself did okay and sold a few hundred copies for me. But I didn’t target the campaign in an optimal way. If you look at the Also Boughts which appeared afterwards, I had lots of books outside my target…

View original post 1,333 more words

May 27, 2018

Syncopation: A Novel of Adele Hugo by Elizabeth Caulfield Felt

19th century France, Nova Scotia, Barbados

Syncopation according to Webster: (music) to shift the regular accent (in a composition) to a normally unaccented beat.

Adèle is born into a perfect family: beautiful mother, two handsome brothers, a sister who is the epitome of a generous spirit and of course a famous father. For the first few chapters, we watch Adèle growing and interacting with her family until the unthinkable happens: the tragic death of a beloved member of the family. A half-beat has been missed; the harmony has been interrupted and can never be the same again.

Adele emerges from the tragedy with a determination never to marry and to live life as she chooses. She comes to resent her domineering father, nor does she respect her mother’s imperatives. No longer is she the darling of the perfect family. While being treated as a pariah by her family, she enjoys a delicious and illicit sex life. Eventually, she escapes the clutches of convention by following a lover to Canada.

Adele is the kind of spunky, liberated woman we admire so much in our heroines. No matter how desperate her circumstances become, she refuses to live the kind of life her family and society try to impose on her. Yet the author doesn’t attempt to hide her warts. As for Victor Hugo, I expected a more progressive man but he is as rigid in his views about women as his daughter is non-conforming.

This is an engrossing story, flawlessly told and with characters that come to life and fill our imaginations to the brim.

*****

May 10, 2018

Coming soon to your favourite bookseller

I have a new book ready for publication. It’s a romantic romp in the time of the War of the Roses with Robbie Ovedale (handsome Northumbrian who likes nothing better than dealing head blows to Scots) and Mary Margaret Douglas (a bit of an Amazon-type with red hair, a bad temper and a dislike of all things English.)

Ignoring the fact that they exist only in my head, I looked for pictures of them. After wasting a good hour of my precious time I gave it up. So use your imagination.

[image error]

Instead, here’s a picture of Northumberland where Robbie lived. Lovely, isn’t it?

I haven’t set a publication day for this one yet. I’m prevaricating. Maybe in June.

April 29, 2018

My review of Triumph of a Tsar by Tamar Anolic

Imagined history or alternative history is not my usual choice, but I thought if the author could make me believe in Tsar Alexei, I could get over my bias. I found Alexei as a 16-year-old to be fun-loving and impulsive; as a man, devoted to duty and his family but rather too prone to tears and saying “I’m sorry.”

The writing is good, with only a few grammatical error or typos and the author did her research. I checked some things that I thought might be incorrect but in each case she was right.

However, my credulity was stretched by some of the sub-plots. Examples: Lenin had an audience and brought a gun along to shoot the Tsar, but instead was shot by Alexei; the Tsar sent his son and heir to kill Hitler; an uncle, or cousin, threw a glass ashtray at the haemophiliac Tsar, did not even apologise and wasn’t punished. Incidents like this make the story unbelievable. Even if it’s alternative history, the author needs to make it believable.

Any story about Russia is bound to be confusing because of the names. So many people had the same name. Many of them also had nicknames. The confusion in this book is compounded by a) the number of characters with the same name b) the use of proper names and nicknames c) having characters of the same name in the same scene. Many times characters were introduced into a scene where they had no part to play. The list of characters at the beginning of the book instead of the end and their relationship to the Tsar would have been helpful. All of this made the story difficult to read.

***

https://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss_2?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=Tamar+Anolic

April 28, 2018

A gentle warning

I am still working on my link to Mailchimp, so please don’t attempt to transcribe yet. This message will be removed when I have my ducks in a row.

April 20, 2018

My review of Irina’s Story by Jim Williams

At the opening of the book, Irina is ninety years old, but she still has a wry sense of humour and all her faculties. The story begins before she was born into a family of a privileged bourgeoisie. It begins toward the end of Imperial Russia and continues through the revolution, wars, the repressions of the Stalin-era, to Moscow of 1990 and the rise of capitalist-leaning gangs.

We first meet her father, the unimaginative and prosaic Nikolai and his more adventurous cousin, Alexander, their wives and others who populate their world. Her handsome father cannot abide Irina because she is a hunchback, while her beautiful mother sees past her deformity and loves her but suffers the guilt of bringing such a creature into the world. This is not so much a matter of strife between the couple but of disappointment with each other, that is never spoken of. Irina stalks through the house, listening at doors and hiding in bushes. From the family’s ‘dinner table talk’ we learn that the seeds of revolution, already sown at the time of the emancipation of the serfs, are germinating.

From her own memories as well as journals and letters she has collected Irina informs us of the politics of the time and the progression of the wars, providing a valuable and relevant background to the stories of the various family members as relationships are destroyed along with the world they once knew. (The murder of the Imperial family is not mentioned.) The author’s knowledge of how war was conducted in those days can only have been the result of extensive research. Either that, or he is over a hundred years old and was there.

There is a cast of colourful characters. Even the weak and unlikeable ones such as Nikolai and the ones who turn into bitches such as Xenia and Adalia manage to evoke our compassion. It was fascinating to watch them change as they learned to cope with their changed circumstances.

This novel is a family saga, a riches to rags story and a tale of unrequited love. It’s also very tragic. For me, it is the best kind of historical novel – a great story that furthered my knowledge of the era. I cannot praise it enough.

*****