Carl Zimmer's Blog, page 58

August 29, 2011

Climate Relicts: My new story for Yale Environment 360

I'm among the 800,000 people in Connecticut without power thanks to Irene, so I won't be blogging much for the foreseeable future. But before I get to other matters like dragging branches around, let me point you to my latest piece for Yale Enivronment 360. I take a look at a new concept called the climate relict. Around the world, there are pockets of plants and animals living hundreds of miles away from their main species ranges. They were left behind in refuges at the end of the last Ice Age, as others moved towards the poles in response to the warming climate. As the climate now warms even more, climate relicts have a lot to teach us about how to manage biodiversity. Check it out.

[Update: bad link to Yale e360 fixed]

August 27, 2011

More on Scientific American Podcast: Science Tattoos and the Myth of the Parasite-Driven Cat Lady

Before Irene takes away my Internet connection, let me point you to part two of my interview on Science Talk, the podcast of Scientific American. (If you missed it, here's part one.)

Talk you on the other side of the maelstrom.

[Update: Part one linked now fixed]

August 25, 2011

Scientific American interviews me about evolution in the city (and more to come)

Steve Mirsky, host of the excellent Science Talk, a podcast at Scientific American, talked to me the other day about all sorts of things. Part one of our talk is now online. We talk about my recent story about evolution in New York City. (Scientific American has a special issue dedicated to cities this month.) Listen to the podcast here.

Steve will be posting the second part of the talk soon.

Ann Coulter Nostalgia: Behold, For *I* Am The Giant Flatulent Raccoon

It's been a while since we've treated to the spectacle of Ann Coulter lecturing about evolution, but she's at it again. She's just written an op-ed in the wake of Rick Perry's recent statement that Texas teaches evolution and creationism [his word] because evolution is "just a theory out there."

It's been a while since we've treated to the spectacle of Ann Coulter lecturing about evolution, but she's at it again. She's just written an op-ed in the wake of Rick Perry's recent statement that Texas teaches evolution and creationism [his word] because evolution is "just a theory out there."

Coulter takes this opportunity to remind us that she dedicated a third of her 2006 book Godless to demolishing evolutionary biology. Apparently the scientists who have published over 59,000 papers on the topic of evolution since she published her book didn't get the memo.

To rectify that situation, Coulter now informs us that "it is a mathematical impossibility, for example, that all 30 to 40 parts of the cell's flagellum — forget the 200 parts of the cilium! — could all arise at once by random mutation."

Of course, nobody is saying they evolved all at once by random mutation. Nobody except for Ann Coulter. To see what scientists are actually saying, you can start by reading this review that presents a detailed hypothesis about the incremental evolution of the flagellum and the cilium, based on actual experiments. In a ...

August 23, 2011

How many species are there? My latest for the New York Times

In 1833, John Obadiah Westwood, a British entomologist, tried to guess how many species of insects there are on Earth. He extrapolated from England to Earth as a whole. "If we say 400,000, we shall, perhaps, not be very wide of the truth," he wrote. Today, scientists have found over a million species of insects and keep finding more every year.

The question of how many species there are on Earth has been a tricky one ever since Westwood's day. I've written a story for the New York Times about a new estimate that was published today: 8.7 million.

What makes the paper particularly interesting is that it introduces a new method for estimating biodiversity. The method is based on Linnean taxonomy. While we have lots of new species left to find, we may have found most of the classes, orders, and phyla. It turns out that for a number of groups–mammals, birds, and so on–the numbers of each of these rankings rise as you descend the hierarchy.

Here's a diagram that summarizes this striking pattern (courtesy of the Census of Marine Life). I couldn't fit it into the story, so I thought I'd show it here:

Zooming In On the Cholera Tree of Life (And Death)

In the wake of last year's earthquake in Haiti, cholera arrived on the island for the first time in 60 years. According to the World Health Organization, 419, 511 Haitians got sick with cholera as of July 31, of which 5,968 died. The infection rate is dropping right now, but the arrival of Hurricane Irene could change that.

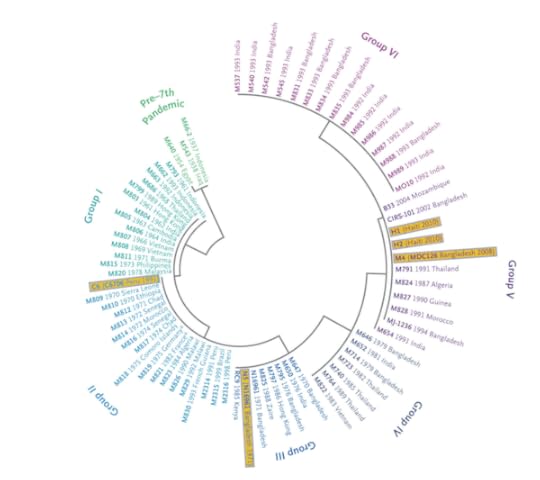

As I wrote in December, scientists applied evolutionary biology to find clues to how cholera–or, more precisely, the bacteria Vibrio cholerae– came to Haiti. They compared the DNA in the strain in Haiti to ones that have been found in other parts of the world. From this analysis, they drew a tree, which I've reprinted below.

The bacteria in Haiti was more closely related to strains in South Asia than ones from South America. So it was unlikely that cholera came to Haiti floating by water from a nearby country. The evolutionary tree led credence to idea that U.N. peacekeeping troops, some of whom came from Nepal, brought it with them by plane. An outbreak of cholera hit Nepal in September 2010, shortly before a battalion of Nepalese peacekeepers left for Haiti.

This analysis was a bit like a ...

August 21, 2011

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Death threats for scientists?

I hate to say I told you so.

A few months ago I was asked to give a couple talks to the skeptic community. Since I had just published a book about viruses, I decided to talk about the way myths so often crop up around them, and how a properly skeptical person should think about viruses. Over the centuries, viruses have been encircled by urban legends, superstitions, and conspiracy theories. The name "influenza" dates back to a time when European physicians believed the flu was due to the influence of the stars. More recently, HIV has been subject to all sorts of myths, from stories that it was created by the CIA to claims that it is not the cause of AIDS. The autism-vaccine controversy has been fueled in part by myths about viruses–namely, that the risk from vaccines is far greater than the risk from viruses like measles.

In my talks, I speculated that the very nature of viruses makes it easy for people to grab onto these kinds of explanations, and to reject scientific evidence that might argue against them. Viruses are the smallest living things on Earth, and yet they can have worldwide effects. They may ...

August 18, 2011

Science writers: You have great powers.

The news these days is grim for the science-minded. The governor of Texas, who'd also like to be your president, says that Texas schools teach creationism. (They don't, although Perry–who appointed a creationist to chair the State Board of Education–may wish otherwise.) Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson spoke passionately on HBO about the country's retreat from dreams.

The news these days is grim for the science-minded. The governor of Texas, who'd also like to be your president, says that Texas schools teach creationism. (They don't, although Perry–who appointed a creationist to chair the State Board of Education–may wish otherwise.) Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson spoke passionately on HBO about the country's retreat from dreams.

So I found some small comfort in an email I got from Patrick House, a Stanford graduate student, about my recent post on the cunning ways of the parasite Toxoplasma–Toxo to its friends and admirers.

I'm the first author on the new Toxo paper. I wanted to send you an email that hopefully cheers your day — I'm getting a Ph.D. now in Neuroscience at Stanford, working exclusively on Toxo — and I wouldn't be here if it weren't for you.

I did my undergrad work in Philosophy (with some neuroscience thrown in) and was perpetually fascinated by Toxo ever since your Discover article on Parasites a decade ago led me tangentially to it and then — of course — Parasite Rex. I met with Robert, spoke to him about ...

August 17, 2011

Fatal Attraction: Sex, Death, Parasites, and Cats

It's time to revisit that grand old parasite, the brain-infecting Toxoplasma. The more we learn about it, the more marvelously creepy it gets.

It's time to revisit that grand old parasite, the brain-infecting Toxoplasma. The more we learn about it, the more marvelously creepy it gets.

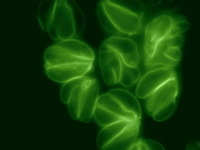

Toxoplasma is a single-celled relative of the parasites that cause malaria. It poses a serious risk to people with compromised immune systems (for example, people with AIDS) and fetuses (which is why pregnant women need to avoid getting Toxoplasma infections). If you've got a healthy immune system, it doesn't cause any immediate harm. (Ed Yong has explained why a purported link to brain cancer is very weak.) All told, perhaps a quarter or a third of all people on Earth carry thousands of Toxoplasma cysts in their heads. Most never become aware of their living cargo.

The Toxoplasma life cycle normally takes the parasite from cats to the prey of cats and back again. In the guts of cats, the parasites have sex and produce egg-like offspring which are shed with cat droppings. They can survive in soil for weeks or months. Rats and other mammals ingest the eggs, which produce cysts mainly in the brain. When the cats eat infected prey, they get infected.

For a little over ten years, scientists have been ...

August 16, 2011

Before Leviathan

The biggest animals on Earth–the biggest animals to have ever lived, in fact–are baleen whales. They can grow to over 100 feet long thanks in part to their ability to snarf colossal amounts of food. To do so, they swing open their toothless lower jaws, which inflate like a parachute with water. Then they haul their lower jaw shut again and then use a titanic tongue to push out a school bus worth of water through a filter. The filter is baleen: a set of fronds that hangs from their upper jaws. They trap shrimp and other tiny creatures in the baleen, which the whales then swallow before preparing for the next gulp. Each one of these operations can snag a blue whale up to half a million calories.

The biggest animals on Earth–the biggest animals to have ever lived, in fact–are baleen whales. They can grow to over 100 feet long thanks in part to their ability to snarf colossal amounts of food. To do so, they swing open their toothless lower jaws, which inflate like a parachute with water. Then they haul their lower jaw shut again and then use a titanic tongue to push out a school bus worth of water through a filter. The filter is baleen: a set of fronds that hangs from their upper jaws. They trap shrimp and other tiny creatures in the baleen, which the whales then swallow before preparing for the next gulp. Each one of these operations can snag a blue whale up to half a million calories.

The baleen whale is a mammal. It rears its young in the womb, complete with a placenta. It makes milk to feed its newborn calves. Yet the baleen whale is obviously a far cry from any mammal on land. This 30-million-year transformation is pretty irresistible, because it's so radical and because it comes into sharper focus as the years go by. ...