Carl Zimmer's Blog, page 56

October 12, 2011

Crystallography in High Heels #scienceink

October 10, 2011

Please welcome Megavirus, the world's most ginormous virus

Starred review for #ScienceInk in Publisher's Weekly: "Breathtaking"

October 6, 2011

The tedious inevitability of Nobel Prize disputes

Once more we are going through the annual ritual of the Nobel Prize announcements. The early morning phone calls, the expressions of shock, the gnashing of teeth in the betting pools. In the midst of the hoopla, I got an annoyed email on Tuesday from an acquaintance of mine, an immunology grad student named Kevin Bonham. Bonham thought there was something wrong with this year's Prize for Medicine or Physiology. It should have gone to someone else.

Once more we are going through the annual ritual of the Nobel Prize announcements. The early morning phone calls, the expressions of shock, the gnashing of teeth in the betting pools. In the midst of the hoopla, I got an annoyed email on Tuesday from an acquaintance of mine, an immunology grad student named Kevin Bonham. Bonham thought there was something wrong with this year's Prize for Medicine or Physiology. It should have gone to someone else.

Kevin lays out the story in a new post on his blog, We Beasties. The prize, he writes, "was given to a scientist that many feel is undeserving of the honor, while at the same time sullying the legacy of my scientific great-grandfather." Read the rest of the post to see why he feels this way.

Kevin emailed me while he was writing up the blog post. He wondered if I would be interested in writing about this controversy myself, to give it more prominence. I passed. Even if I weren't trying to carry several deadlines on my head at once, I would still pass. As I explained to Kevin, I tend to steer clear of Nobel controversies, because I think the prize is, by definition, a lousy way to recognize important science. All the rules about having to be alive to win it, about how there can be no more than three winners–along with the lack of prizes for huge swaths of important scientific disciplines–make these kinds of disputes both inevitable and tedious.

The people behind the Nobel Prize, I should point out, have done a lot of good. Their web site is a fine repository of information about the history of science. I've tapped it many times while working on books and articles. There's also something pleasing to see the world drawn, for a couple days at least, to the underappreciated byways of science. If the Nobel Prize makes more people aware of quasicrystals, the Prize is doing something unquestionably wonderful.

But the vehicle that delivers this good is fundamentally absurd. The Nobel Prize rules say no more than three people can win an award, for example. This year's prize for physics went to Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, Adam Riess for their work on the dark energy that is accelerating the expansion of the universe. Half went to Perlmutter, and a quarter went to Riess and Schmidt. But, of course, scientists do not work in troikas. It wouldn't even make sense to say that three people could accept the prize on behalf of three labs. Science is a stupendously complex social undertaking, in which scientists typically become part of shifting networks over the course of many years. And those networks are not just made up of happy friends collaborating on projects together. Rivals racing for the same goal can actually speed the pace towards discovery. Now, some individual scientists are certainly remarkable people, but the Nobel Prize doesn't merely recognize them for being remarkable individuals. The citations link each person to a discovery, as if there was some sort of equivalence between the two. But discoveries are usually a lot bigger than one person, or even three.

In his wonderful book The 4% Percent Universe, Richard Panek describes the history of the dark energy research that led to this year's physics prize. I read the book to review it for the Washington Post, and I was particularly taken by a story at the end. In 2007, the Gruber Prize, the highest prize for cosmology research, was awarded for the research. Schmidt haggled with the prize committee until they agreed to widen the prize to all 51 scientists who had been involved in the two rival teams. Thirty-five of them traveled to Cambridge for the ceremony. It would have been fun to watch Schmidt go up against the Nobel Prize committee. He would have lost, of course, but at least he would have made an important point.

Should scientists get credit for great work? Of course. But that's what history is for. Charles Darwin and Leonardo da Vinci never got the Nobel Prize, but somehow we still manage to remember them as important figures anyway. The time that's spend arguing over whether someone should get fifty percent of a prize or twenty-five percent or zero percent could be spent on much better things, like more science.

October 4, 2011

Holes in the net: A podcast of my Story Collider tale

Story Collider is a monthly performance where people tell stories about science. (Think The Moth in a lab coat.) The organizer, Ben Lillie, invited me to tell a personal story about the place of science writing in my life. I decided to talk about a memorable night in South Sudan, when I wondered what I was living for.

I told the story to a great crowd at Union Hall in Brooklyn last week. And you can hear the podcast at the Story Collider web site. Check it out.

October 3, 2011

Slime molds creep into the New York Times

My editor at the New York Times called me a few weeks ago and said, "Slime molds! Can you write something about them?" Moments like that fill me with gratitude.

My editor at the New York Times called me a few weeks ago and said, "Slime molds! Can you write something about them?" Moments like that fill me with gratitude.

Here's my story, on the cover of tomorrow's Science Times. I look at how they solve the evolutionary puzzles of altruism, build highway systems, and turn out to be some of the oldest life forms on land.

(And for more on the ever-expanding worldwide diversity of slime mold, check out the Eumycetezoan Project.]

[Image: myriorama/Flickr via Creative Commons]

October 1, 2011

Tom Clynes on arsenic life

Yesterday I wrote about the arsenic life saga, prompted by a long retrospective feature by Tom Clynes in Popular Science. While I recommend the piece, I expressed reservations because it passed along the "scientists besieged by bloggers" spin on the events, when the actual history doesn't support that.

Yesterday I wrote about the arsenic life saga, prompted by a long retrospective feature by Tom Clynes in Popular Science. While I recommend the piece, I expressed reservations because it passed along the "scientists besieged by bloggers" spin on the events, when the actual history doesn't support that.

Clynes (whom I've never met) emailed me in the evening with this comments, which he allowed me to share:

Carl,

Thanks for your comment on my Popular Science feature on Felisa Wolfe-Simon's arsenic-life saga. In some ways, I think you're on target, though I would like to provide a bit of clarification: Throughout the story, when I convey an argument made by someone who's on one side of the issue or another, it doesn't mean that I necessarily buy into that argument.

To that end, I'd like to add a bit of context to a paragraph that you quote, regarding the storm of criticism and the paper's authors going "underground." You follow the excerpt with your comment that "Clynes has us believe that this barrage of extraordinary, brutal criticism (or perhaps questions from journalists) forced Wolf-Simon and her colleagues to go into witness protection."

Actually, I don't believe that, nor would I have my readers believe it. I think it would have been useful to your readers for you to have included my next paragraph, which makes it clear that I am in fact spotlighting both sides of a polarized dialogue regarding this particular point:

Microbiologist Jonathan Eisen of the University of California at Davis called the lack of response "absurd" and told Carl Zimmer from Slate, "They carried out science by press release and press conference. They are now hypocritical if they say that the only response should be in the scientific literature."

Though I didn't state my opinion in the story (better for readers to decide for themselves), I will here: I think that Eisen is on the money here.

Some other opinions: Do I think that the arsenic-life paper was flawed? Yes. Do I think it that some of its conclusions will be dissolved by further investigation? Yes. Do I believe that NASA's hyped-up approach to publicizing what was actually a rather understated paper was ham-handed, and damaging to everyone involved? Big time.

Do I think the paper never should have been published? No. In a profession where young scientists are advised to avoid controversy as they build their careers, Wolfe-Simon pushed against a paradigm and sought answers to some very big questions. She passed through the same peer-review hoops (imperfect as they may be) at Science as other scientists must. Yes, her research was imperfect and yes, she likely overreached—but plenty of scientific papers are flawed, and many young researchers go too far. If scientists aren't willing to subject themselves to the possibility of failure, science can't possibly progress.

Critically, there's nothing to indicate that Wolfe-Simon did anything unethical, which might have justified the shrill tone and sweeping proportions of the response—and the fact that she was singled out among the paper's 11 authors. True, she was the lead author, and it was her hypothesis. But it's surprising that Ron Oremland, the lab director and principal investigator, is rarely mentioned in the criticisms.

If my story has a bottom line, it's in this quote by the University of Colorado's Alan Townsend: "Absent major ethical violations, no junior scientist full of passion for an idea deserves crucifixion for a professional failure or two. If a paper is flawed, it should be dismissed. The scientist should not."

September 30, 2011

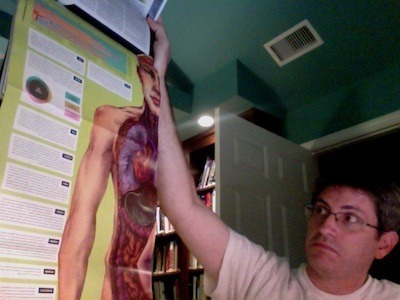

My kind of centerfold

The folks at Wired recently asked me to put together a guide to the human ecosystem. You can get it in the October issue as a centerfold–the kind of centerfold that shows someone who took off the clothes, and then took off the skin. Bugs in your eyes, in your ears, in your gut, influencing your mind and health–they're all there. Check it out.

The folks at Wired recently asked me to put together a guide to the human ecosystem. You can get it in the October issue as a centerfold–the kind of centerfold that shows someone who took off the clothes, and then took off the skin. Bugs in your eyes, in your ears, in your gut, influencing your mind and health–they're all there. Check it out.

#ArsenicLife Goes Longform, And History Gets Squished

If you haven't been tracking the arsenic life saga closely over the past ten months, check out Tom Clynes's big feature at Popular Science. It focuses on the travails of Felisa Wolfe-Simon, the lead author on the paper, who has gone from the Olympian heights of TED talks to getting "evicted" from the lab where she's worked for the past couple years. (Her word.)

For those of us who've been tracking the story for a while, that last fact popped out. Wolfe-Simon had been working in the lab of her co-author Ronald Oremland, but that's now over. Let's recall that her senior colleagues dubbed the intriguing microbe she studied GFAJ-1, for "Get Felicia A Job."

It's a good article. I won't be forgetting the opening scene anytime soon, when Wolfe-Simon is ambivalently posing for a television crew, and she sinks into the mud of Mono Lake, where she first encountered GFAJ-1.

But I do share some of the reservations that science writer David Dobbs expresses over at his blog Neuron Culture. As a genre, the profile is one of the most addictive and enjoyable of all. It doesn't matter if the profile is of a hero or a scoundrel; the story is good as long as it's full of human nature in all its extremes. But profiles of scientists are tricky, because science transcends any single individual scientist. To do the science justice, you may need to pull the spotlight away and get into the less human stuff, like chemical reactions and pH levels.

The story thus focuses mainly on Wolfe-Simon, with scientific critics effectively reduced to mean chair-throwers, their scientific objections dispatched in a couple lines. People and events are relevant insofar as they affect Wolfe-Simon. And in the process, Clynes writes some mystifying stuff:

What made the level of criticism so extraordinary is that the paper, in itself, is not so flawed that it should not have been published. The argument was compelling, the conclusions were measured, the data was thorough, and the paper made it through the same peer-review process as other articles in Science.

And Clynes has us believe that this barrage of extraordinary, brutal criticism (or perhaps questions from journalists) forced Wolf-Simon and her colleagues to go into witness protection:

Overwhelmed with questions from the media, Wolfe-Simon went underground. Guided by NASA's PR team, she and Oremland and the paper's other co-authors began citing NASA spokesperson Dwayne Brown's position that the authors would not be responding to individual criticisms. The agency, Brown said, didn't feel it appropriate to debate science using the media and bloggers. Discourse should occur in scientific publications.

"I wasn't hiding, but I didn't want to get involved in a Jerry Springer situation, with people throwing chairs," Oremland says. "There are hundreds of blogs some viable and some off the wall, and they all want an immediate response. To try to engage in scientific commentary that way seems like a descent into madness."

What the–?

I've seen this version of the arsenic life story before, and I can say (as one of the people mentioned in Clynes's story) that it simply does not square with the facts. I really hope it doesn't get set in people's minds like concrete.

Let's just run through the timeline, shall we?

Thursday, December 2: An eagerly anticipated NASA press conference, the publication of the paper in Science, front-page news in leading newspapers, with no articles I'm aware of dealing seriously with the critics.

Saturday, December 4: Rosie Redfield, a microbiologist with a blog she mainly uses for her class, expresses deep skepticism. It is the only such blog post I know of that presented a detailed criticism at this point in the timeline.

Sunday, December 5: Alex Bradley, another microbiologist, guest-blogs at We Beasties in a similar vein. The criticisms are harsh but deal in the scientific details of the paper.

The audience for both posts is small–an audience of fellow microbe junkies.

By Sunday afternoon, I think it's time to write something. I'm wondering if Redfield and Bradley are saying what a lot of other scientists are thinking. I start getting in touch with leading experts in the areas that the paper touches on. In the next couple days they will get back to me, and just about all of them say the paper has serious problems, one simply declaring it should never have been published.

Naturally, it's only fair to give the authors of the study a chance to respond. So on Sunday afternoon, I send links to the two blog posts above to Oremland and Wolfe-Simon. Oremland promptly writes back, "Sorry, but 'nope.'"

I'm a bit surprised and email back to find out why. Here's what I get:

It is one thing for scientists to "argue" collegially in the public media about diverse details of established notions, their own opinions, policy matters related to health/environment/science.

But when the scientists involved in a research finding published in scientific journal use the media to debate the questions or comments of others, they have crossed a sacred boundary.

Monday, December 6: Wolfe-Simon emails back at 12:42 AM, a few hours after I emailed her. She cc's all her co-authors and administrators at NASA, including the director of the astrobiology program:

Mr. Zimmer,

I am aware that Dr. Ronald Oremland has replied to your inquiry. I am in full and complete agreement with Dr. Oremland's position (and the content of his statements) and suggest that you honor the way scientific work must be conducted.

Any discourse will have to be peer-reviewed in the same manner as our paper was, and go through a vetting process so that all discussion is properly moderated. You can see many examples in the journals Science and Nature, the former being where our paper was published. This is a common practice not new to the scientific community. The items you are presenting do not represent the proper way to engage in a scientific discourse and we will not respond in this manner.

Regards,

Felisa

In the morning I get busy on my story. That evening, the CBC comes out with a story focused on Redfield's complaint, relaying NASA's statement that it's not appropriate for scientists to debate each other in the media. I scratch my head and get back to work.

Tuesday, September 7: I publish a story in Slate about arsenic life, describing the detailed criticisms of a number of scientists (which I've posted in full on the Loom). I quote the no-comments of Oremland and Wolfe-Simon.

—Now, we can have a fine debate about whether journalists should ask scientists to respond to criticism from other scientists about their work. Oremland and Wolfe-Simon may truly believe that this crosses a sacred boundary. I say it doesn't. It's standard practice. Science, where the arsenic life paper was published, lets reporters get their hands on papers early, and reporters regularly seek out other scientists for comments on those papers before publishing their articles. If two scientists post their thoughts on public blogs, there is no difference in asking authors of a paper to respond to their critiques. Trying to make such a distinction is pointless.

I've been doing this kind of thing for a long time, and I have never encountered a response like this one from the hundreds of scientists I've interviewed. And that includes scientists who work for or are sponsored by NASA, despite the claims that popped up that NASA policy forbids such open debate. In fact, the scientist who gave me the headline for my story–"This Paper Should Not Have Been Published"–is herself part of NASA's astrobiology team. Did she say, "Mister, you've crossed a sacred boundary"? Nope. She wrote me a long, detailed explanation of why she thought the paper failed.

In other words, I'm pretty sure I'd win that debate.

But the story you get from Clyne and others is not that Oremland and Wolfe-Simon had some a priori policy never to deign to comment on criticism that weren't published in a scientific journal. It's that they were overwhelmed by Jerry Spinger-grade hordes of unseemly scientist bloggers and relentless journalists–so overwhelmed that they had to vanish. They were victims.

But for this version of events to be true, the hordes must have stormed their lab in a single day–at some point between Saturday, when Redfield posted her critique, and Sunday, when the scientists told me they wouldn't comment for the story. As far as I can tell, there were just two blog critiques published during that time, and a CBC news article. If someone can point to any evidence of this alleged horde that I've somehow missed–perhaps the gnawed bones of some graduate student left in its trail–I'd love to see it.

Otherwise, this just seems like one of those stories that sounds good in hindsight. And if any good is going to come out of this strange saga, we should strive to get all its stories straight.

Celluloid Science: October 20 at the New York Academy of Sciences

Let's just pretend for a moment that this theater is showing a thrilling movie about Cambrian fossils, shall we? And to further that dream, join me in October for "Celluloid Science," a talk about science and the movies at the New York Academy of Sciences. It's part of the NYAS "Science & The City" series.

Let's just pretend for a moment that this theater is showing a thrilling movie about Cambrian fossils, shall we? And to further that dream, join me in October for "Celluloid Science," a talk about science and the movies at the New York Academy of Sciences. It's part of the NYAS "Science & The City" series.

Here are the details from the event web site…

Celluloid Science: Humanizing Life in the Lab

Thursday, October 20, 2011 | 7:00 PM – 8:30 PM

The New York Academy of Sciences, 7 World Trade Center

If you know anything about science, you understand that it is a highly complex human endeavor that mixes perseverance and luck, eccentricity and training, feasts and famines. As a medium, film has the potential to bring us into the inner world of science, breaking down misconceptions about the nature of science by creating an alternative narrative.

Science & the City teams with the Imagine Science Film Festival (ISFF) to present a panel discussion about telling the stories of science through film. Moderating this panel will be author Carl Zimmer. On the panel will be Sean Carroll, PhD (evolutionary biologist and founder of the Howard Hughes Medical institute's Documentary Institute); David J. Heeger, PhD (neuroscientist who studies the brains under the influence of cinematic stimuli); Darcy Kelley, PhD (biologist at Columbia University); and Valerie Weiss, PhD (scientist and award-winning writer and director, Losing Control).

It's a ticketed event, but you, my dear Loominaries, can get $15 off full-price tickets by using the promo code SPKR15. Register here.

[Image: Photo by Kevin H./Flickr]