Natylie Baldwin's Blog, page 4

September 24, 2025

Trump – NATO Should Shoot Down Russian Aircraft that Enter Their Airspace

By Dave DeCamp, Antiwar.com, 9/23/25

President Trump said on Tuesday that NATO countries should shoot down Russian aircraft that enter their airspace, comments that come as tensions are soaring between Moscow and the Western military alliance in Eastern Europe.

The president made the comments when meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York City. “Yes, I do,” Trump said when asked if NATO should shoot down Russian aircraft that enter its airspace.

His comment came on the same day that NATO held Article 4 talks over allegations from Estonia that Russian jets had, for 12 minutes, entered the airspace of Vaindloo, an uninhabited island in the Gulf of Finland that belongs to Estonia and is located approximately 15 miles north of the country’s coast.

For its part, Russia has called Estonia’s allegations baseless, and the Russian Defense Ministry stated that the jets were on a scheduled flight to Kaliningrad, claiming that the “flight path lay over the neutral waters of the Baltic Sea, more than three kilometers from the island of Vaindloo.”

During the NATO Article 4 consultations on Tuesday, NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte acknowledged the Russian jets posed no threat. “In the latest airspace violation we discussed today in Estonia, NATO forces promptly intercepted and escorted the aircraft without escalation, as no immediate threat was assessed,” he said.

When asked if NATO would shoot down any manned or unmanned Russian aircraft that enters its airspace, Rutte said, “Decisions on whether to engage intruding aircraft, such as firing upon them, are, of course, taking in real time, are always based on available intelligence regarding the threat posed by the aircraft, including questions we have to answer like intent, armament and potential risk to Allied forces, civilians or infrastructure.”

While NATO countries recently shot down drones in Poland, which they alleged were launched by Russia, shooting down a manned jet would mark a significant escalation and could lead to a full-blown war between the alliance and Russia, which could quickly turn nuclear.

His comment came on the same day that NATO held Article 4 talks over allegations from Estonia that Russian jets had, for 12 minutes, entered the airspace of Vaindloo, an uninhabited island in the Gulf of Finland that belongs to Estonia and is located approximately 15 miles north of the country’s coast.

For its part, Russia has called Estonia’s allegations baseless, and the Russian Defense Ministry stated that the jets were on a scheduled flight to Kaliningrad, claiming that the “flight path lay over the neutral waters of the Baltic Sea, more than three kilometers from the island of Vaindloo.”

During the NATO Article 4 consultations on Tuesday, NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte acknowledged the Russian jets posed no threat. “In the latest airspace violation we discussed today in Estonia, NATO forces promptly intercepted and escorted the aircraft without escalation, as no immediate threat was assessed,” he said.

When asked if NATO would shoot down any manned or unmanned Russian aircraft that enters its airspace, Rutte said, “Decisions on whether to engage intruding aircraft, such as firing upon them, are, of course, taking in real time, are always based on available intelligence regarding the threat posed by the aircraft, including questions we have to answer like intent, armament and potential risk to Allied forces, civilians or infrastructure.”

While NATO countries recently shot down drones in Poland, which they alleged were launched by Russia, shooting down a manned jet would mark a significant escalation and could lead to a full-blown war between the alliance and Russia, which could quickly turn nuclear.

Euronews: Russia to respect nuclear arms limits with US for one more year, Putin says

, 9/22/25

The New START deal, signed by then-US and Russian presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev, limits each country to no more than 1,550 deployed nuclear warheads and 700 deployed missiles and bombers.Russia’s President Vladimir Putin said on Monday that Moscow will adhere to nuclear arms limits for one more year after the last remaining nuclear pact with the United States expires in February.

Putin said that the termination of the New START agreement would have negative consequences for global stability.

Speaking at a meeting with members of Russia’s Security Council, he said that Russia would expect the US to follow Moscow’s example and also stick to the treaty’s limits.

The New START, signed by then-US and Russian presidents, Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev, limits each country to no more than 1,550 deployed nuclear warheads and 700 deployed missiles and bombers.

Its looming expiration and the lack of dialogue on anchoring a successor deal have worried arms control advocates.

The agreement envisages sweeping on-site inspections to verify compliance, but they have been dormant since 2020.

In February 2023, Putin suspended Moscow’s participation in the treaty, saying Russia could not allow US inspections of its nuclear sites at a time when Washington and its NATO allies openly declared Moscow’s defeat in Ukraine as their goal.

Moscow has emphasised, however, that it was not withdrawing from the pact altogether and would continue to respect the caps on nuclear weapons the treaty has set.

Prior to the suspension, Moscow claimed it wanted to maintain the treaty, despite what it called a “destructive” US approach to arms control.

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told reporters it was necessary to preserve at least some “hints” of continued dialogue with Washington, “no matter how sad the situation is at the present time.”

“We consider the continuation of this treaty very important,” he said, describing it as the only one that remained “at least hypothetically viable”.

“Otherwise, we see that the United States has actually destroyed the legal framework” for arms control, he said.

Together, Russia and the United States account for about 90% of the world’s nuclear warheads.

The future of New START has taken on added importance at a time when Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has pushed the two countries closer to direct confrontation than at any time in the past 60 years.

In September last year, Putin announced a revision to Moscow’s nuclear doctrine, declaring that a conventional attack by any non-nuclear nation with the support of a nuclear power would be seen as a joint attack on his country.

The threat, discussed at a meeting of Russia’s Security Council, was clearly aimed at discouraging the West from allowing Ukraine to strike Russia with longer-range weapons and seems to significantly reduce the threshold for potential use of Russia’s nuclear arsenal.

Putin did not specify whether the modified document envisages a nuclear response to such an attack.

However, he emphasised that Russia could use nuclear weapons in response to a conventional attack posing a “critical threat to our sovereignty,” a vague formulation that leaves broad room for interpretation.

September 23, 2025

Reuters: Ukraine struggles to identify the remains of thousands of its soldiers

By Olena Harmash, Reuters, 9/15/25

KYIV, Sept 16 (Reuters) – It’s more than a year since Anastasiia Tsvietkova’s husband went missing fighting the Russians near the eastern city of Pokrovsk, and she doesn’t know whether he’s alive or dead.

Russia does not routinely provide information about those captured or killed, and there has been no news from fellow soldiers or the International Red Cross, which can sometimes visit prisoner-of-war camps.

If Yaroslav Kachemasov was indeed killed on the front, then the recent repatriation of thousands of bodies might at least allow Tsvietkova to grieve.

Yet even that still seems a remote prospect, as Ukraine’s forensic identification laboratories are overwhelmed not only by the sudden arrival of so many bodies, but also the difficulty of identifying remains that may be burned or dismembered.

TRACING UKRAINE’S WAR DEAD: DNA AND DETECTIVE WORK

The 29-year-old dentist living in Kyiv submitted a sample of her husband’s DNA, filled in dozens of forms, wrote letters and joined social media groups as she sought information.

Kachemasov, 37, went missing during his second combat mission near Pokrovsk, which Russia has been attacking for months. The place where he disappeared is now occupied by Russia.

“The uncertainty has been the toughest,” Tsvietkova told Reuters. “Your loved one, with whom you have been together day in, day out for 11 years – now there is such an information vacuum that you simply don’t know anything at all.”

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, hundreds of thousands have been killed or wounded on both sides. At least 70,000 Ukrainian soldiers and civilians have been reported missing.

In the last four months, more than 7,000 mostly unidentified bodies have been brought to Ukraine in refrigerated rail cars and trucks, the piles of white plastic sacks a grim reminder of the cost of the worst conflict in Europe since World War Two.

GRISLY WORK OF IDENTIFYING BODIESReuters spoke to eight experts including police investigators, the interior minister, Ukrainian and international forensic scientists and volunteers, and visited a forensic DNA laboratory in Kyiv.

Many of the bodies are decaying or in fragments, so such labs are key to identifying them. But the process of establishing and matching each DNA profile can take many months.

Since 2022, the Interior Ministry has expanded its DNA laboratories to 20 from nine, and more than doubled the number of forensic genetics scientists to 450, according to Ruslan Abbasov, a deputy director of the ministry’s forensic research centre.

But the start of large-scale swaps was a shock.

“We were used to one, two, three, 10 (bodies), and they would come in slowly,” he said at a laboratory on the outskirts of Kyiv.

“Then it was 100, then it was 500. We thought 500 was a lot. Then there were 900, there were 909 and so on.”

Experts in protective gear and disposable overalls run DNA tests and match profiles to missing persons. But some cases are so complicated that it can take up to 30 attempts to find a DNA match.

Ukraine has only recently begun routinely collecting DNA samples from serving soldiers in case of disappearance or death, so investigators often face the much trickier task of using relatives’ DNA to find a match.

SOLDIERS’ BODIES A REMINDER OF UKRAINE’S LOSSESAs well as being a logistical challenge, the sudden influx of remains has served as a reminder of Ukraine’s losses.

Authorities in Kyiv and Moscow have been generally tight-lipped about the overall numbers of soldiers killed and wounded.

In June, the U.S.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, opens new tab estimated that more than 950,000 Russians had been killed or wounded in the war so far, against 400,000 Ukrainians.

According to official figures, as of last month Ukraine had received 11,744 bodies. But 6,060 of these came in June alone, and another 1,000 in August.

Ukrainian authorities declined to provide a figure for how many bodies Ukraine had sent back to Russia; it is a figure that could hint at how much territory Kyiv’s forces are losing, where they are unable to recover their dead.

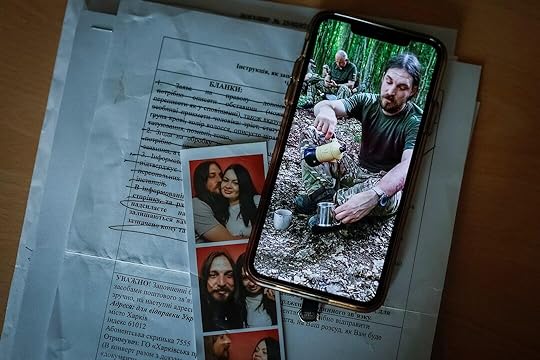

Item 1 of 7 A photo of 37-years-old Yaroslav Kochemasov, serviceman of the National Guard of Ukraine, who was declared missing-in-action in Donetsk region, is displayed on a phone of his wife Anastasiia Tsvietkova, 29, amid Russia’s attack on Ukraine, in Kyiv, Ukraine, August 6, 2025. REUTERS/Alina Smutko

Russian officials said they had received just 78 in June. Moscow’s Ukraine negotiator, Vladimir Medinsky, suggested Ukraine was dragging its feet – something Kyiv denies.

Interior Minister Ihor Klymenko accused Russia of complicating the identification process by handing over some of the bodies in a disorderly way.

“We have many cases, probably hundreds, when we have remains of one person in one bag, then in a second and in a third,” he said at his ministry.

Klymenko also said Ukraine had so far identified at least 20 bodies belonging to Russian servicemen – something for which Medinsky said there was no evidence.

The Moscow Defence Ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

DNA SAMPLES KEY TO IDENTIFICATIONSince June 2022, the International Committee of the Red Cross has participated in more than 50 repatriation operations and also helped Ukraine with refrigerated trucks, body sacks and protective gear, said ICRC forensics coordinator Andres Rodriguez Zorro.

Once the bodies are in Ukraine, refrigerated trucks deliver them to morgues in different cities and towns.

In one of Kyiv’s morgues at the end of June, around a dozen men in white protective suits opened a refrigerator truck carrying about 50 bodies and carefully unloaded the white body bags.

As each was opened for checks, a sharp, sickly sweet smell filled the air. Investigators then took out smaller, black bags containing a body or body parts.

Police investigator Olha Sydorenko, explained that initial checks were for unexploded ammunition, and also uniforms, documents, tags and other personal belongings.

“We assign each body a unique identification number that accompanies them until the remains find their home,” she said outside the morgue – adding that she had got used to the smell.

She and her colleagues are the first point of contact for families of missing soldiers.

After learning from military authorities that her husband was missing in action, Tsvietkova opened a criminal case with the National Police, as prescribed, and submitted a description.

“… everything that could help identify him. That is … his tattoos, his appearance, scars, moles,” she said.

She had one advantage – a sample of his DNA. “I brought his comb.”

LABS WORK IN SHIFTS, DEFYING POWER CUTSBut with so many bodies in the morgues, Klymenko said it could take 14 months to identify them all.

His teams work most hours of the day. The pristine lab in Kyiv is equipped with generators and batteries for potential power outages, which have become common as Russia bombs Ukraine’s electricity grid.

Teams work in shifts to maximise the use of space and equipment. The labs take samples from bodies and from relatives of the missing, usually when none of the missing soldier’s DNA is available.

“Sometimes you need to collect not only one sample from a relative, sometimes you need to collect two, three, or four samples,” said the ICRC’s Zorro. “We are talking about hundreds of thousands of samples to be compared.”

Abbasov said the most difficult cases were when bodies had been burnt and their DNA had been degraded.

But Tsvietkova doesn’t want her husband identified by his DNA.

“… I’m waiting for Yaroslav to come back alive,” she said.

“I top up his (mobile phone) account every month so that he gets to keep his phone number. I write to him every day, telling him how my day went, because when he returns there will be a whole chronology of events that I lived through all this time, without him.”

Additional reporting by Alina Smutko, Anna Voitenko in Kyiv and Iryna Nazarchuk in Odesa; Editing by Mike Collett-White and Kevin Liffey

September 22, 2025

Russia Matters: Russia’s Drone Use in Ukraine War Surges Nearly Ninefold

Russia Matters, 9/19/25

In the past four weeks (Aug. 19–Sept. 16, 2025), Russia has gained 226 square miles of Ukraine’s territory, according to the Sept. 17, 2025, issue of the Russia-Ukraine War Report Card. In comparison, Russia gained 237 square miles during the previous four-week period (July 22–Aug. 19, 2025), while average Russian monthly gains have been 169 square miles so far this year, according to the card. Comparing shorter periods, Russia gained 91 square miles of Ukraine’s territory in the week of Sept. 9–16, 2025, up from a 14 square mile gain the previous week, which constitutes an increase of 550%.Russia has dramatically increased attack drone production in 2025, launching over 34,000 kamikaze drones and decoys at Ukraine—nearly nine times more than in the same period last year, Ukrainian and U.S. officials told The New York Times. This increase follows “a huge surge in one-way attack drone production” in Russia, according to a Sept. 14 article in NYT. “Russia is now able to produce about 30,000 of the attack drones modeled on the Iranian design per year [and] some believe the country could double that in 2026,” NYT reported. In July 2025 alone, Russian forces used nearly 6,300 attack drones against Ukraine—up from just 426 the previous July, according to The Wall Street Journal, which estimates that Russia has significantly escalated strikes on Ukraine since Donald Trump took office.This week’s Russian-Belarusian “Zapad-2025” military exercises—observed by a few U.S. and NATO representatives— reportedly gamed out scenarios involving the use of non-strategic (tactical) nuclear weapons. The drills included simulated nuclear strikes, evaluation and deployment of Russia’s new road-mobile “Oreshnik” intermediate-range missile system and integration of dual-use Iskander-M missiles in Kaliningrad. The exercises, involving some 41 training grounds, 100,000 service personnel and about 10,000 pieces of weapons, also featured simulated launches from submarines and tactical aviation strikes.1 In his public remarks at the strategic wargame, Vladimir Putin refrained from explicitly referring to any nuclear weapons components of Zapad-2025, but he did mention the involvement of “strategic aviation,” which consists of Russian long-range bombers capable of carrying nuclear weapons, in the game.U.S. President Donald Trump told Fox News the U.S. would help “secure the peace” after Russia’s war in Ukraine concludes even though Vladimir Putin had “really let me down,” reiterating his belief that allies must end purchases of Russian oil to increase pressure: “Very simply, if the price of oil comes down, Putin is going to drop out… He’s going to have no choice.” Trump added he would consider more actions to punish Putin, but insisted further U.S. efforts depend on whether European partners “stop purchasing oil from Russia.” Separately, bipartisan U.S. senators introduced legislation to sanction Russia’s shadow oil fleet and LNG projects, even as the Trump administration itself held off on new Russia sanctions, conditioning future steps on NATO unity in banning Russian oil imports.2The European Commission unveiled the EU’s 19th sanctions package against Russia on Sept. 19, targeting energy, technology and finance. The new measures include a complete ban on Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports from January 2027. The 19th package also places sanctions on 118 additional “shadow fleet” oil tankers, asset freezes on major energy traders and tighter controls on crypto platforms and banks tied to Russian transactions. Trade restrictions are also extended to companies in Russia, China and India that help Moscow skirt sanctions, and 45 more firms were blacklisted for supporting Russia’s defense sector.3 It should be noted that the EC previously proposed a ban on EU imports of Russian gas and LNG by the end of 2027 .James Carden: Sixty-Three Years, Nothing Has Changed

By James Carden, Landmarks Magazine, 8/29/25

Editor’s note: this piece is republished with the author’s permission, it first appeared at The Realist Review.

Exactly 63 years ago, on a summer afternoon in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Kennedy White House adviser, Arthur Schlesinger, returned to Harvard where he had, until recently, been a professor of history.

Schlesinger had come at the invitation of another Harvard professor, Dr. Henry Kissinger, who in those years directed the Harvard International Seminar, which brought together the “best and the brightest” from here and abroad to lecture, compare notes—and perhaps most importantly to Kissinger, to network.

What Schlesinger said that day is worth recalling in some detail because it bears directly on our present situation.Pledge your support

Schlesinger told the assembled that, “As the functions of the national government have multiplied, a bureaucracy developed dominated by vested interests of its own—vested interests in ideas, in procedures, in institutions.”

“The American government,” said Schlesinger, “has today four, not three, coordinate branches—the legislative, the judiciary, the executive and the presidency; and an active President would encounter as much resistance within the executive branch as he would from Congress or the Supreme Court. The increase in the size of the bureaucracy created a split between the “political government” and the “permanent government”; and many members of the bureaucracy exuded the feeling that Presidents come and go, but they go on forever.”

The problem of moving forward—said Schlesinger— was in great part “the problem of making the permanent government responsive to the policies of the political government.”

Schlesinger warned that the “permanent government” has within its power the “capacity to dilute, delay, obstruct, resist and sabotage presidential purposes.”

At the heart of this was a general misunderstanding: Most assumed that as the US had grown more powerful, so too did the office of the Presidency. But Schlesinger said that was not the case. In some respects, “the President today is less free to act on his own” than was “the President fifty or a hundred years ago.”

By the end of the 1960s it was becoming apparent that the President was in many respects the most-prized prisoner of the permanent government.

A government which he was elected to oversee.

In a 1971 essay titled “The National Security Managers and the National Interest,” Richard Barnet, a founder of the Institute for Policy Studies, observed that, “National Security Managers exercise their power chiefly by filtering the information that reaches the President and by interpreting the outside world for him.”

Picking up on Barnet’s theme, the philosopher Hannah Arendt observed that, the President, who is “allegedly the most powerful man in the most powerful country, is the only person in this country whose range of choices can be predetermined.”

Indeed, by the end of 1960s it had become clear that the national security state aggregated to itself the right to oppose—and if necessary thwart through a variety of means—the foreign policy initiatives of a duly-elected President.

To Arendt, the turning point was the assassination of President Kennedy. “No matter how you explain it and no matter what you know or don’t know about it,” said Arendt, “it was quite clear that now, really for the first time in a very long time in American history, a direct crime had interfered with the political process. And this somehow changed the political process.”

In this context, another philosopher, Paul Grenier, has observed that, “Nothing provides a more vigorous basis for action and control than fear.”

This being so, every future administration has understood the unspoken prerogative of accommodating itself to the agenda of the permanent state.

By the end of the 1960s the permanent state emerged as the supreme arbiter of policy—who would dare contradict it?

After the Kennedy assassination came Vietnam; and Vietnam was predicated on certain Cold War myths, namely, the Domino Theory and the evergreen Munich Analogy. Most of the men Kennedy brought with him into high office knew the public rationale for the war were nonsense; this became clear with the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971.

Now let me return to Arendt. In a review of the Pentagon Papers for the New York Review of Books, she observed that “the policy of lying “ – that is lying by the government – “was hardly ever aimed at the enemy but was destined chiefly, if not exclusively, for domestic consumption, for propaganda at home, and socially for the purpose of deceiving Congress.”

***

In the late 1970s, there came a further innovation courtesy of President Jimmy Carter and his national security adviser, Zbiginew Brzezinski.

During a commencement address at the University of Notre Dame in May of 1977, Carter declared that US foreign policy must be “based on fundamental values.” Prefiguring the current mania within Democratic foreign policy circles over what is said to be a division of the world between democracies and autocracies, Carter claimed that, “Because we know that democracy works, we can reject the arguments of those rulers who deny human rights to their people…we can no longer separate the traditional issues of war and peace from the new global questions of justice, equity, and human rights.”

Brzezinski sought to make this rather too broad conception of American foreign policy even more encompassing, advising Carter to see human rights as “much more than political liberty, the right to vote, and protection against arbitrary governmental action.”

No: It should encompass almost every aspect of a country’s political, economic and social life. It was the opposite of the foreign policy recommended by the diplomat-historian George F. Kennan, who had written that the “moral obligations of governments are not the same as those of the individual.” For Kennan, the “primary obligation” of government “is to the interests of the national society it represents, not to the moral impulses that society may experience.”

Kennan condemned what he saw as “the histrionics of moralism” by which he meant “the projection of attitudes, poses, and rhetoric that cause us to appear noble and altruistic in the mirror of our own vanity but lack substance when related to the realities of international life.”

What made Carter’s fusing of human rights to foreign policy so seductive was that it dovetailed nicely with the long preoccupation with the so-called “Lessons of Munich”—namely, that had Chamberlain not “appeased” Hitler in 1938 and instead fought a preemptive war right then and there, things would have turned out much differently—for Hitler and, especially, for the Jews of Europe. This had been a Democratic and Republican talking point for decades: Truman invoked its lessons in justifying Korea, as did Johnson in Vietnam—later both Bushes invoked it as justification for their respective wars in Iraq.

While it seems unlikely that it was Carter’s intention to do so, a foreign policy that prioritized human rights provided future administrations with a high-minded, ready-to-hand rationale that they could dust off and use when it suited them. Human rights widened the scope for American intervention— and it drove the Munich mindset into overdrive.

A quicker study than Carter, Brzezinski seemed to grasp the implications of this line of thinking almost immediately. As the State Department historian Louise Woodroofe has noted, Brzezinski understood “that underlying forces such as grassroots movements, nationalism, technology and the role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOS), and even climate change would continue to factor into understanding the state of the world.”

In this respect, Brzezinski’s crystal ball was better than most—in later decades the permanent state, under the guise of human rights, harnessed the power of NGOS and grassroots organizations (invariably funded by US and NATO-allied governments) to influence the political life of other nations, particularly in the post-Soviet space.

This way of approaching foreign policy resulted in our misguided, indeed – in the case of Ukraine – disastrous enthusiasm for color revolutions.

And, as we have seen, these wars by stealth, empowered certain of our agencies, while disempowering others. The agencies best able to carry operations in the name of human rights and democracy were not the traditional centers of diplomatic engagement or even those reservoirs of hard power like the Army and Navy.

No, this way of conducting foreign policy empowered the intelligence apparatus, special ops, and “soft power” agencies like USAID— as well as government-funded NGOS that could provide the president and the executive branch with plausible deniability.

What Trump plans to do to address this state of affairs remains, at best, a mystery.

September 21, 2025

The Grayzone: BBC Media Action: Britain’s overseas info warfare unit

By Kit Klarenberg, The Grayzone, 9/2/25

Though BBC Media Action (BBCMA) portrays itself as the “international charity” of the British state broadcaster, files show the group frequently carries out politically-charged projects overseas with government funding. Furthermore, the group consistently trades upon the BBC’s reputation and its intimate “links” with the British state broadcaster when pitching for contracts with donors, including the Foreign Office, which operates in tandem with MI6.

The leaks reveal that BBCMA’s work is explicitly “driven by a social and behaviour change communication approach.” The organization’s “project design” is informed by “psychology, social psychology, sociology, education and communication,” and consideration of “the specific factors that can be influenced by media and communication that could lead to changes in behaviours, social norms and systems” in foreign countries. Which is to say, BBCMA is concerned with psychological warfare, warping perceptions and driving action among target audiences.

“We recognise that different formats achieve different things when it comes to change… and consider audience needs, objectives and operational context when deciding which format to use,” BBCMA asserts in one file. In another, the organization crows, “people exposed to our programming are more likely to: have higher levels of knowledge on governance issues; to discuss politics more; to have higher internal efficacy (the feeling that they are able to do something); and participate frequently in politics.”

BBCMA’s internal research indicates audiences exposed to the organization’s “output” are widely encouraged into “taking action,” and concluded: “At scale this is powerful.” A cited example was BBCMA’s production of a “long-running” radio drama in the former British colony of Nigeria, Story Story, which reached an estimated 26.5 million people across West Africa. Surveys indicated 32% of listeners “did something differently as a result of listening” to the program – of those, 40% were persuaded to vote differently in the country’s elections.

BBCMA has operated at once secretly and in plain sight since its 1999 founding. The leaked files’ contents raise obvious, grave questions not only about the organization’s activities globally, but whether BBC staffers who conduct overseas missions for Media Action truly cease being intelligence-connected state propagandists and information warriors when they return to their day jobs in London, producing ‘factual’ and entertainment content for the British state broadcaster.

Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine in BBCMA’s crosshairsIn February 2021, The Grayzone exposed how BBCMA managed covert programs training journalists and cultivating influencers in Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, while helping produce news and entertainment programming for local media outlets pushing pro-NATO messaging. These activities were funded by the British Foreign Office, forming part of a wider clandestine effort by London to “weaken the Russian state’s influence” at home and in neighboring states.

Another previously unreported component of this malign initiative saw BBCMA channel £9 million ($12.8 million) in government funds from 2018 to 2021 into “innovative… media interventions” which targeted citizens of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine via “radio, independent social media channels, and traditional outlets.” The project was managed and coordinated directly by BBCMA from BBC Broadcasting House, in London. Thomson Reuters Foundation, the global newswire’s “non-profit” wing, supported the effort via Reuters offices in Kiev and Tbilisi.

BBCMA and the Thomson Reuters Foundation (TRF) operatives met in private every four months to discuss the operation’s progress with representatives of the Foreign Office, and British embassies in the three target countries. In advance of the project, the pair leveraged their “strong profile” in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to conduct “broad consultations” with neighborhood news outlets, media organizations and journalists.

The National Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine (UA:PBC) was offered “essential support,” aimed at “improving its existing programs” and “developing new and innovative formats for factual and non-news programs.” The broadcaster was reportedly “very interested” in BBCMA developing a “new debate show” and “discussion programming” on its behalf. Additionally, BBCMA was “already working on building the capacity” of nationalist Ukrainian outlet Hromadske, which was also receiving funding from the US government via USAID.

Meanwhile, BBCMA visited the offices of Georgia’s Adjara TV “to discuss training priorities and possible co-productions.” The station was especially keen to develop “youth programming” – “a gap in the market” locally. BBCMA and TRF furthermore proposed to tutor and support ostensibly “independent” online Georgian news portals like Batumelebi, iFact, Liberali, Monitor, Netgazeti, and Reginfo. “Local” and “hyperlocal” media platforms, as well as “freelancer journalists,” bloggers and “vloggers” were also considered important targets. “Mentors” were “embedded” in target outlets, providing “bespoke support across editorial, production and wider management systems and processes as well as on the co-production of content.” Those “mentors” included current and former BBC reporters.

“Our ability to recruit talented and experienced BBC staff is a great asset which will be harnessed for this initiative,” BBCMA bragged. The British state broadcaster was glowingly described as “well-known and highly regarded” in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, and thus well-placed to begin “encouraging” journalists to meet with “local stakeholders,” including politicians, in order to “cement the media as a key governance actor” in the region. This would hopefully ensure “a more enabling operating environment” for secretly British-sponsored “independent” media platforms.

The “long track record” of BBCMA and TRF in conducting comparable efforts elsewhere had purportedly “shifted government policy.” This included states “experiencing Arab uprisings.” Elsewhere, BBCMA cited TRF establishing “the award-winning Aswat Masriya” in Egypt as a major success. As The Grayzone revealed, this secretly British-funded, Reuters-run outlet worked overtime to undermine Cairo’s first democratically elected leader, Mohamed Morsi, and helped lay the foundation for his removal by a violent military coup in July 2013.

Seemingly emboldened by this experience, BBCMA proposed the Thomson Reuters Foundation create a comparable “news platform” in Ukraine which was “timed for the run up to the 2019 elections,” which ultimately put Volodymyr Zelensky on the world stage.

The pair planned to “replicate” the exercise for Georgia’s elections the following year. “This platform” – “staffed entirely by local editors and journalists,” the BBCMA wrote, “would publish independent and vetted news content, freely syndicated to local and national media,” and “provide a vital service.”

London exploits BBCMA to ‘hold governments to account’The unified nature of BBCMA and the British state broadcasting body of the BBC is undeniable in leaked documents related to the former’s activities in the former Yugoslavia. Submissions to the Foreign Office boast, “BBC Media Action was created to harness the reputation; resources and expertise of the BBC…[its] trainers and consultants are working journalists, editors and producers with substantial newsgathering, programme-making and editorial experience in the BBC.” A specific selling point was BBCMA’s “access to the wider BBC’s wealth of experience and talent.”

This global army of BBC apparatchiks “have a wide range of format and production experience with partners and beneficiaries including factual programming, dramas and the development of social media.” Media outlets in which BBCMA’s operatives are embedded are also granted access “to a broad range of innovative digital tools” created by the British state broadcaster, and “BBC connected studios.”

A BBCMA pitch for a Foreign Office project set to run from 2016 to 2019, ostensibly concerned with “promoting freedom of expression and public dialogue” in Serbia and Macedonia, proposed a team comprised almost exclusively of BBC veterans, some of whom had occupied senior positions with the British state broadcaster for decades. One had worked for BBC World Service’s Bulgarian division since the 1980s, eventually leading the entire operation from 1996 to 2005.

Their CV states they managed “all aspects of BBC broadcasting to Bulgaria, including strategy, editorial supervision; budget and staff management and training,” while “negotiating and achieving partnerships with Bulgarian radio stations and other media and representing the BBC in the target area.” Another had likewise headed numerous divisions of the British state broadcaster at home and abroad over their lengthy career, and was credited with “masterminding election and other big-story coverage”.

This experience may be relevant to a prior BBCMA project, cited in the leaked pitch. From November 2015 to March 2016, the organization “worked on helping the Macedonian media to effectively cover elections.” As The Grayzone has revealed, Macedonia’s 2016 election was triggered by an MI6-sponsored “colorful revolution”, which dislodged a popular nationalist administration from power. In its place, a doggedly pro-Western government scraped into office. We can only speculate whether BBCMA’s clandestine sway over how local news outlets reported the vote influenced its outcome.

That the Foreign Office uses BBCMA – and the BBC by extension – for nakedly political interference overseas is spelled out in leaked documents detailing yet another covert British safari in the Balkans. While ostensibly concerned with “supporting greater media independence” in the region, BBCMA acknowledged that its news reporting was “a means to an end.” The ultimate objective, according to the internal documents, was holding “governments and powerful entities to account” should they fail to act as required by London.

BBCMA Balkanizes the BalkansAccording to BBCMA documents, Britain sought to “contest the information space” throughout the Balkans through a series of campaigns to “diversify the information, sources and perspectives available” to local populations. In this case, diversity was a clear subtext for amplifying pro-NATO, UK-centric viewpoints.

BBCMA goals included “supporting current and future media outlets, actors and journalists to provide high-quality output and content, and to operate safely, sustainably and more viably.” For instance, the supposed charity proposed a “training and mentoring” initiative, which would “prioritise female defence and diplomacy journalists.”

“As well as developing current journalists, in order to create a pipeline of future women, the programme will include an outreach element with activities undertaken in universities to encourage women to consider journalism as a career,” BBCMA pledged. This would not only bring “female journalists to the forefront of the industry’s consciousness” in the region, but “improve the perception of the UK with these participants, who are influencers in the Western Balkans.”

The funding proposal sent by BBCMA to the FCO reveals the extent of their contempt for women and the working class, who were meant to be targeted with fictionalized content rather than hard news. “Drama can be a useful tool for engaging poorer and female audiences,” BBCMA explained.

BBCMA further pledged to “support the creation of new media” across the region, assisting “entrepreneurs to establish new media titles” that would amplify “independent, local voices.” Britain was described as “expert at providing the space and opportunity” for news “start-ups.” London’s overt backing of such projects explicitly aimed to exploit the dearth of job opportunities on the local scene to “increase positive perception of the UK with younger target audiences.” Among the outlets to be bankrolled would be a regional “news wire” producing “quality content (written, images, and video).”

Also among the proposals were so-called “Citizen Content Factories,” consisting of “two-week long, highly-publicised, content creation camps” in the Western Balkans. These British-backed summer camps would “bring young people from across the region together for a YouTube training and partnership camp that will teach young people to become content producers” as well as “provide a very public programme of activity that will improve the perception of the UK.”

Elsewhere, popular local vloggers would be employed to produce videos “in which they share highly inflammatory disinformation, some of which will include conspiracy theories about NATO, before revealing that it is fake and calling out their follower community for possibly believing them.” The rationale was, “audiences dislike being accused of succumbing to disinformation,” which would in turn make them dismissive of facts and perspectives unwelcome to the British Foreign Office. In practice, the campaign seemed designed to taint all criticism of NATO as potential disinformation.

BBCMA also sought to recruit and cultivate a legion of “opinion formers” across diverse fields, particularly in London’s “priority areas of defence, security and diplomacy… who will be advocates for the UK” in the West Balkans. Associated activity included training “young people to become content producers” and “news generators,” via a “citizen content factory.” Media training programs would enable BBCMA assets “to become more effective public speakers,” and the organization would “then work with media partners in-country to provide opportunities for them.”

No area of the West Balkans was considered off-limits to BBCMA. A “media literacy roadshow” would tour “rural areas and towns” throughout the region. “Areas outside major cities” were “identified as priorities due to the smaller information environment of which they are likely to be part.” Even schools were proposed for infiltration, with BBCMA stating local curriculums should be reviewed to “ensure explicitly recognising disinformation is included.” If not, “an education package could be created” with “pre-created lesson plans and materials” for teachers.

One document boasted that BBCMA had dedicated offices in 17 countries on every continent, employing hundreds of people. At the time it was written, BBCMA was managing 68 “live projects, with most offices running several simultaneous programmes.” The organization’s intimate connections to BBC World Service, active in “more than 100 cities globally,” meant BBCMA’s information warfare could reach audiences totaling hundreds of millions worldwide.

September 20, 2025

Harrison Berger: How U.S. Support for Ukraine’s Neo-Nazis Imperils Diplomacy

By Harrison Berger, The American Conservative, 8/29/25

As a negotiated settlement of the Russia–Ukraine war becomes more likely, President Volodymyr Zelensky faces a major obstacle to peace that comes not from Moscow, but from ultranationalist and neo-Nazi forces inside his own country.

In a recent interview with the Sunday Times, Serhii Sternenko—a leader of the paramilitary group Right Sector, which was founded by neo-Nazis—warned Zelensky that if he ceded any territory to Russia in a peace deal, “he would be a corpse—politically, and then for real.”

Though the Times presents him merely as a “civil activist,” Sternenko served as the head of Right Sector’s Odessa branch, where he oversaw the extremist group’s 2014 crime spree that culminated in the Odessa trade union hall massacre in which militants used Molotov cocktails to burn alive more than 40 antigovernment protestors.

The Times characterizes the Odessa trade union hall massacre as mere “clashes” and fails to attribute the violence to any one particular side, despite the fact that the Right Sector proudly claimed responsibility for it.

Whitewashing Ukraine’s ultra-nationalist right is neither new nor accidental. As the late Stephen Cohen, an eminent scholar of U.S.–Russia relations, warned nearly a decade ago, Western journalists and officials, by downplaying Ukraine’s right-wing militant groups and parroting Kiev’s official claims about them, empowered violent extremists.

The resurgence of Ukraine’s right-wing extremist forces is inseparable from U.S. policy since 2014, when the U.S. facilitated the overthrow of a democratically elected government in Kiev. While Ukrainian liberals participated in the “Maidan Revolution,” the muscle was provided by right-wing extremist groups, which the West bestowed with legitimacy and, eventually, access to arms and funding. What began as the whitewashing of neo-Nazi vigilantes became the normalization of neo-Nazi battalions, which are now embedded in Ukraine’s security elite.

That those same right-wing extremist forces, nurtured by the United States and NATO, now threaten to sabotage a peace deal and overthrow the Zelensky government reveals a bizarre paradox at the heart of our involvement in Ukraine that has yet to be confronted:

Washington interfered in Ukrainian domestic politics and helped finance a proxy war with Russia ostensibly to save Ukrainian democracy from tyranny. But under U.S. tutelage—and in service of proxy war aims—Ukraine has rapidly descended into a more authoritarian state.

Western whitewashing of Ukrainian Nazis is not an aberration of the past decade. Rather, it is consistent with a U.S. strategy that began during the Cold War of recruiting, laundering, and weaponizing extremist forces.

One of the earliest and clearest cases of this strategy was the CIA’s decision to protect rather than prosecute Ukraine’s wartime nationalists, who had openly collaborated with Nazi Germany and perpetrated the mass murder of Jews and Poles. Among them was Stepan Bandera and his OUN-B militant group, which aligned itself with Ukraine’s Nazi “liberators” within the first days of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa in 1941, when the Axis powers invaded the Soviet Union.

America’s nascent post-war national security state, despite its awareness of Bandera’s Nazi crimes and his organization’s status as “primarily a terrorist organization,” protected Bandera from extradition to the Soviet Union, recruiting him and other known OUN-B Nazi collaborators through programs like the CIA’s Project AERODYNAMIC, aimed at “exploitation and expansion of the anti-Soviet Ukrainian resistance for cold war and hot war purposes.”

Rather than being a source of national shame for Ukraine, its Nazi collaborators are the core icons of Ukrainian nationalism and a source of pride.

Along with Bandera, historical war criminals like Roman Shukhevych—the commander of the OUN-B’s paramilitary wing—have been posthumously venerated by various Ukrainian governments. Both figures were awarded the official title “Hero of Ukraine” in 2007 and 2010, respectively. Bandera’s birthday continues to be celebrated with annual torchlight marches across the country.

During the Maidan uprising in 2014, neo-Nazi militias inspired by Stepan Bandera and associated with Ukraine’s right-wing extremist Svoboda party used sniper rifles to massacre protestors—both pro- and antigovernment—as well as police.

Though the Maidan massacre trials would later pin responsibility for the violence on neo-Nazi paramilitaries from the Right Sector and the political party Svoboda, the chaos was immediately seized upon by the Obama administration to demand the removal of Ukraine’s democratically elected president, Victor Yanykovych, who was instantly blamed for it all.

A leaked U.S. State Department call arguably reveals how career diplomat Victoria Nuland arranged for Svododa leader Oleh Tyahnybok to have a position of influence in Kiev’s post-revolution government, saying her handpicked Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk should “be on the phone” with the Svoboda leader “four times a week.” The notorious call, along with other evidence of U.S. support for anti-Yanykovych forces, has led many to conclude the “Maidan Revolution” was in fact a U.S.-backed coup.

Washington’s decision in 2014 to protect and empower the extremist groups which perpetrated the Maidan massacre would entrench an ultranationalist and neo-Nazi element within Ukrainian politics that would later sabotage efforts for peace with Russia.

When Zelensky came to power on a promise to resolve the conflict with Russia in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region, Cohen predicted that the new president’s peace efforts would likely face heavy and possibly violent resistance from the ultranationalist factions that Washington had recently empowered. “His life is being threatened by a quasi-fascist movement,” Cohen warned.

The Biden administration did not look the other way in the face of those extremist forces threatening Zelensky—it looked directly at them and in June 2024 decided to remove State Department restrictions on funding the Azov Battalion, allowing the U.S. government to lavish the neo-Nazi group with weapons.

Under the patronage of President Joe Biden and NATO, Azov—whose members often openly wore Nazi insignia—metastasized from a battalion into an entire brigade integrated into Ukraine’s National Guard.

Biden’s policy was at least consistent, conforming with a decades-long policy of protecting, retooling, and empowering violent extremist groups whenever they served the interests of unelected national security state elites, in this case, anti-Russian neocons.

Earlier this year, Azov further consolidated its influence within Ukraine’s national security apparatus by expanding into multiple corps. Its political reach grew in parallel, with members appointed to key government positions, including Oleksandr Alferov as Director of the Institute of National Memory, giving the neo-Nazi group direct influence over both security policy and the framing of Ukraine’s historical narrative.

Violent Ukrainian nationalist forces like Right Sector, Azov, and Sternenko’s militants have become indispensable foot soldiers in Washington’s project, and therefore their lengthy record of violence and terrorism has been obscured. Even as Zelensky now faces threats to his life from these same forces, they are still celebrated in Western media as heroes of democracy.

The paradox is revealing: The very groups hailed as Ukraine’s “defenders of democracy” are also those eroding it from within, threatening to assassinate the president if he pursues peace. Though an unintended consequence, this perilous dynamic flows from U.S. policy and reveals its true aims.

The U.S. strategy in Ukraine was never about protecting Ukrainian democracy. It was—as Biden’s Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin admitted—about sustaining a proxy war to “weaken Russia.” The emergence of violent antidemocratic forces in Kiev has not been a casualty of that strategy, but its central instrument.

September 19, 2025

Andrew Korybko: The SCO & BRICS Play Complementary Roles In Gradually Transforming Global Governance

By Andrew Korybko, Substack, 9/2/25

The recent SCO Leaders’ Summit in Tianjin drew renewed attention to this organization, which began as a means for settling border disputes between China and some former Soviet Republics but then evolved into a hybrid security-economic group. Around two dozen leaders attended the latest event, including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who paid his first visit to China in seven years. Non-Western media heralded the summit as an inflection point in the global systemic transition to multipolarity.

While the SCO is more invigorated than ever given the nascent Sino-Indo rapprochement that the US was inadvertently responsible for, and BRICS is nowadays a household name across the world, both organizations will only gradually transform global governance instead of abruptly like some expect. For starters, they’re comprised of very diverse members who can only realistically agree on broad points of cooperation, which are in any case strictly voluntary since nothing that they declare is legally binding.

What brings SCO and BRICS countries together, and there’s a growing overlap between them (both in terms of members and partners), is their shared goal of breaking the West’s de facto monopoly over global governance so that everything becomes fairer for the World Majority. To that end, they seek to accelerate financial multipolarity processes via BRICS so as to acquire the tangible influence required for implementing reforms, but this also requires averting future domestic instability scenarios via the SCO.

Nevertheless, the BRICS Bank complies with the West’s anti-Russian sanctions due to most members’ complex economic interdependence with it, and there’s also reluctance to hasten de-dollarization for precisely that reason. As for the SCO, its intelligence-sharing mechanisms only concern unconventional threats (i.e. terrorism, separatism, and extremism) and are hamstrung to a large degree by the Indo-Pak rivalry, while sovereignty-related concerns prevent the group from becoming another “Warsaw Pact”.

Despite these limitations, the World Majority is still working more closely together than ever in pursuit of their goal of gradually transforming global governance, which has become especially urgent due to Trump 2.0’s casual use of force (against Iran and as threatened against Venezuela) and tariff wars. China is at the center of these efforts, but that doesn’t mean that it’ll dominate them, otherwise proudly sovereign India and Russia wouldn’t have gone along with this if they expected that to be the case.

The processes that are unfolding will take a lot of time to complete, perhaps even a generation or longer, due in no small part to leading countries like China’s and India’s complex economic interdependence with the West that can’t abruptly be ended without dealing immense damage to their own interests. Observers should therefore temper any wishful thinking hopes of a swift transition to full-blown multipolarity in order to avoid being deeply disappointed and possibly becoming despondent as a result.

Looking forward, the future of global governance will be shaped by the struggle between the West and the World Majority, which respectively want to retain their de facto monopoly and gradually reform this system so that it returns to its UN-centric roots (albeit with some changes). Neither maximalist scenario might ultimately enter into force, however, so alternative institutions centered on specific regions like the SCO vis-à-vis Eurasia and the AU vis-à-vis Africa might gradually replace the UN in some regards.

September 18, 2025

Brian McDonald: The ghost in the Kremlin’s corridors: Yevgeny Primakov’s lasting power

By Brian McDonald, Substack, 8/24/25

You may not know of Yevgeny Primakov. But he really should be a household name: because his shadow still tilts across the table whenever the Kremlin weighs its hand. To make sense of the way Russia now speaks, you have to look back to the man who first inscribed those habits into the bones of its statecraft during the devastating 1990s.

The current talks with the United States won’t lead to Obama-era resets or Reagan-esque grand bargains. What Moscow wants is simpler: a) time, b) leverage, and c) a spread of options. It’s a style of diplomacy Primakov would have recognised instantly.

Back in the 1990s, when Boris Yeltsin was raising toasts in Washington and ending his address to the US Congress with “God bless America,” Primakov kept his distance. A trained Arabist, journalist and intelligence man who rose to become foreign minister and then prime minister, he had spent too long in Cairo, Baghdad and Damascus to buy into the mood music of “partnership.”

He grasped, far quicker than most of his peers, what the so-called post-Cold War order really had in store for Russia. Essentially it boiled down to servitude with a smile: a junior chair at the grand table, with a polite grin for the cameras and a signature scrawled on whatever demands the West thought fit to slide across. His answer was to repurpose Karl Deutsch and J. David Singer’s 1960s concept of multipolarity: better to court many princes than bend the knee to one.

At the heart of his politics lay a set of instincts honed by hard experience: never get boxed into someone else’s binaries and guard sovereignty the way a poor man guards his last coin. You should reach out, yes, and build ties with any power that offers the chance, but don’t ever shackle yourself. And as for ideology; use it if you must, but never repeat the Soviet mistake of letting it dictate everything. For Primakov, the only philosophy worth carrying was the blunt survival of the national interest.

His name reached Western headlines in March 1999. On his way to Washington as prime minister, he learned that NATO had begun bombing Serbia and responded by ordering his plane to turn around mid-Atlantic and fly back to Moscow. The gesture announced that the gig was up and Russia wouldn’t be nodding along politely as the West dismantled Yugoslavia. For many Russians, it was the first sign in a decade of collapse that at least one of their leaders still had a spine. However, in a host of Western capitals, it was the moment Primakov was marked as a spoiler.

That same year, he was briefly spoken of as Yeltsin’s possible successor. Many in a Russia battered by economic collapse and humiliated abroad seemed to yearn for his steadiness and dignity. Yet his political star dimmed quickly, outmanoeuvred by the oligarchic Kremlin clan that would ultimately place the much younger Vladimir Putin in power.

Primakov never wore the crown of the presidency, but his way of seeing the world seeped into the bloodstream of the man who did. Putin came out of the shadows at the millennium with the instincts of a security official rather than a statesman. It was Primakov’s frame that gave those instincts shape and turned watchman’s reflexes into a doctrine of state.

Of course, the critics keep their ledger handy. They point at the 1998 financial crash on his watch as prime minister, and say he was no wizard of economics. They recall his unbending hand in Chechnya. Both fair charges, maybe. But whenever the talk turns to foreign policy, the tone completely changes. Here the clarity still lingers because he saw with cruel precision that Russia could never be folded into a Western-centred order without shrinking itself to fit. As a result, he sketched an alternative.

You can still trace his hand in Moscow’s conduct. Talks with Washington are stripped of both the begging bowl and the sabre-rattle. What you find instead is a patience that borders on the obstinate; we can call it strategic waiting. The bet is simple: unpopular governments in Paris, Berlin and London (just look at current polls) will fall with the seasons, but Putin’s Russia will outlast them. In the meantime it probes at the seams of Western unity, leaving a door ajar for any thaw that might drift in with a change of weather.

Even the scaffolding of BRICS or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation shows Primakov’s imprint. These aren’t anti-Western clubs so much as post-Western stages; built to shrink the US-led bloc from lead actor to one among many in a larger cast.

This sets him apart from other Russian visionaries. Vladislav Surkov’s notion of a “Great North,” uniting Russia with Western Europe, collapsed almost as soon as it was uttered. Mikhail Gorbachev’s “Common European Home” dissolved into smoke. Primakov had seen the futility long before. He never believed Russia could be integrated into Western structures on anything other than subservient terms.

So the moves you see out of Moscow today are part of a strategy long-aged, like spirits resting in a dark barrel and waiting for the moment to be poured. In essence, Russia won’t barter away its red lines in Eastern Europe for a scrap of sanctions relief. Nor will it march dutifully in the slipstream of a US–China collision. Instead, it will manoeuvre always under its own steam.

Primakov was born in Kiev in 1929, grew up in Tbilisi, and was educated in Moscow. As mentioned at the outset, he worked as a reporter and analyst of the Arab world before becoming a trusted envoy, then rose to head the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence service. Yeltsin made him chief diplomat in 1996 and prime minister in 1998. He died in 2015 at the age of 85, honoured with a state funeral. Both Putin and Dmitry Medvedev paid tribute to him as a man who had kept Russia’s dignity intact in its hardest modern decade.

Once upon a time, he was whispered about as Yeltsin’s natural heir. However, in the end, his fate was not to rule, but to leave his doctrine behind; to shape Russia’s course long after his physical life had come to an end. That, ultimately, is Primakov’s bequest: it’s why the men in Washington no longer face the pliant Russia of the 1990s, but a state seasoned by the humiliation of those years. Once burned, it now carries the scars. And this time, whatever else happens, it will not come cap in hand.

September 17, 2025

Euronews: Foreign troops in Ukraine would be ‘legitimate targets for destruction,’ Putin says

, 9/5/25

Moscow will consider any foreign troop deployment on Ukrainian soil as “legitimate targets for destruction”, Russian President Vladimir Putin said on Friday.

“If any troops appear there, especially now, during the fighting, we assume that they will be legitimate targets for destruction,” Putin emphasised in his keynote speech at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok.

“And if decisions are reached that will lead to peace, to long-term peace, then I simply see no point in their presence on Ukrainian territory.”

“If these agreements are reached, no one doubts that Russia will implement them in full.”

Putin’s comments came after Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, accompanied by his French counterpart Emmanuel Macron, shared on Thursday that 26 European states, part of the so-called Coalition of the Willing, were prepared to offer security guarantees to Ukraine in a post-war capacity following any potential peace settlement.

Ukraine’s European partners have not suggested sending combat troops to Ukraine during the ongoing war, but instead deploying a type of international peacekeepers only after a possible ceasefire or a peace deal.

These forces would not engage in fighting but would only be tasked with monitoring and maintaining peace after the agreement is reached.

The Russian president voiced doubts about this possibility, though, saying it will be “practically impossible” to reach an agreement on key issues with Ukraine to end the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion, currently in its fourth year.

Putin also said that Russia wants to get security guarantees as well, without specifying what these measures could be and how they would protect Russia in its all-out war against Ukraine.

“Peace guarantees must be for both, Russia and Ukraine,” stressed Putin.

Putin reiterated Moscow’s resolute rejection of Ukrainian membership in the NATO defence alliance. At the same time, the Kremlin is not opposed to Ukraine’s desire to join the European Union, according to him.

He claimed that “Ukraine’s decision on NATO cannot be considered without looking at Russia’s (security) interests”, but Kyiv’s EU aspirations are a “legitimate choice”.

“I repeat, (Ukraine’s EU bid) is Ukraine’s legitimate choice, how to build its international relations, how to ensure its interests in the economic sphere, with whom to enter into alliances.”