Natylie Baldwin's Blog, page 27

April 27, 2025

VIDEO: Flashback to 2000, Putin’s view on NATO

YouTube link here.

In an interview with David Frost 25 years ago, Putin said “I cannot imagine my own country in isolation from Europe.”

April 26, 2025

Russia Matters: Putin Hosts Witkoff on Ukraine Again, As Trump Hopes for Peace Soon

Russia Matters, 4/25/25

Trump wrote on Truth Social on April 20, 2025 that he hoped Russia and Ukraine “will make a deal this week,” and then told Time on April 22 that he thinks such a deal is possible with Zelensky remaining in power. Trump also told Time that “Crimea will stay with Russia” and that “I don’t think they [Ukrainians] will ever be able to join NATO.” The next day saw Trump lash out at Zelenskyy’s refusal to recognize the loss of Crimea, arguing that that “Crimea was lost years ago,” claiming that “nobody is asking Zelensky to recognize Crimea as Russian territory,” according to Reuters . In his turn Putin has reportedly offered to halt his invasion across the current front line and said he was open to direct talks with Kyiv on a peace deal, according to FT and NYT . Putin stated his readiness for direct talks prior to hosting Steve Witkoff for the fourth time to discuss the direct talks. The two had a 3-hour conversation in the Kremlin on April 25 in what “allowed Russia and the United States to further bring their positions closer together, not only on Ukraine but also on a number of other international issues,” according to ,Putin’s foreign policy advisor Yuri Ushakov. Shortly after the Moscow meeting ended, Trump said he heard that his envoy and Putin had “a pretty good meeting,” according to Reuters . Ukrainian and European officials pushed back this week against some U.S. proposals on how to end Russia’s war in Ukraine , making counterproposals on issues from territory to sanctions, according to the full texts of the proposals seen by Reuters. The sets of proposals from talks between U.S., European and Ukrainian officials in Paris on April 17 and in London on April 23 laid bare the inner workings of the shuttle diplomacy under way as Donald Trump seeks a quick end to the war, Reuters reported. See RM’s comparison of the two proposals in Table 1 below:Table 1

The U.S. proposal for Russian-Ukrainianpeace discussed by the high-ranking U.S., European and Ukrainian officials on April 17 in Paris. The European-Ukrainian proposal for Russian-Ukrainian peace discussed by the lower-level U.S. officials with European and Ukrainian officials on April 23 in London. The U.S. proposal calls for a “de jure” U.S. recognition of Russian control in Crimea plus “de-facto recognition” of the Russia’s occupation of nearly all of Luhansk oblast and the occupied portions of Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. (Reuters, 04.25.25, Axios , 04.23.25)The Ukrainian-European proposal defers detailed discussion about territory until after a ceasefire is concluded, with no mention in the document of recognizing Russian control over any Ukrainian territory. (Reuters, 04.25.25)The U.S. proposal calls for the return of the small part of Kharkiv oblast Russia has occupied. It also calls for the unimpeded passage of the Dnieper River, which runs along the front line in parts of southern Ukraine.( Axios , 04.23.25) We could not find any language in descriptionsof the proposal, but assume that a European-Ukrainian proposal would welcome return of Ukrainian territory to Kyiv’s control.On Ukraine’s long-term security, the U.S. proposal states Ukraine will have a “robust security guarantee” with European and other friendly states acting as guarantors. It gives no further detail on this but says Kyiv will not seek to join NATO. (Reuters, 04.25.25, Axios , 04.23.25)The Ukrainian-European proposal says there will be no limits on Ukrainian forces and no restrictions on Ukraine’s allies stationing their military forces on Ukrainian soil — a provision likely to irk Moscow. It proposes robust security guarantees for Kyiv including from the United States with an “Article 5-like agreement,” a reference to NATO’s mutual defense clause. (Reuters, 04.25.25)The U.S. proposal notes that Ukraine could become part of the European Union. ( Axios , 04.23.25)We could not find any language in descriptionsof the Ukrainian-European proposal, but assume that a European-Ukrainian proposal would reaffirm Ukraine’s path to EU.The U.S. proposal says that sanctions in place on Russia since its 2014 annexation of Crimea will be removed as part of the deal under discussion. (Reuters, 04.25.25)The Ukrainian-European proposal says that “US sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014 may be subject to gradual easing after a sustainable peace is achieved” and that they can be re-instated if Russia breaches the terms of the peace deal. (Reuters, 04.25.25)The U.S. proposal says Ukraine will be compensated financially, without giving the source of the money. (Reuters, 04.25.25, Axios , 04.23.25)The Ukrainian-European proposal proposes Ukraine receives financial compensation for damage inflicted in the war from Russian assets abroad that have been frozen (R euters , 04.25.25)The U.S. proposal calls for Russia’s enhanced economic cooperation with the U.S., particularly in the energy and industrial sectors. ( Axios , 04.23.25) We could not find any language in descriptionsof the Ukrainian-European proposal, but assume it won’t contain such a call.The U.S. proposal calls for he Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant to considered as Ukrainian territory but operated by the U.S. ( Axios , 04.22.25) We could not find any language in descriptionsof the Ukrainian-European proposal, but recall that Russia has in the recent past rejected offers of U.S. operation of this NPP.In the past month (March 25–April 22, 2025), Russia gained 166 square miles. (Area equivalent to about 1 ½ Nantucket island), according to the April 23, 2025 issue of the Russia-Ukraine War Report Card . In the past week Russia gained 40 square miles (the equivalent of about 2 Manhattan islands)—a slow down as compared to the previous week’s 50 square miles in the war, which “Ukraine’s ex-chief commander Valerii Zaluzhnyi has described as being in a “stupor.” According to Ukraine’s DeepState OSINT group’s map, as of April 25, 2025, Russian forces occupied a total 112,643 square kilometers of Ukrainian land (43,491 square miles), which constituted 18.7% of Ukrainian territory. In Russia’s Kursk region, Ukraine gave up 14 square miles of control: down to only 5 square miles; nearly concluding its complete withdrawal from Russia. Britain is likely to abandon plans to send thousands of troops to protect Ukraine because the risks are deemed “too high,” according to The Times of London. Britain and Europe would no longer have a ground force guarding key cities, ports and nuclear power plants to secure the peace, this newspaper reported. Instead, the focus for a security commitment to Ukraine would be on the reconstitution and rearmament of Kyiv’s army, with protection from the air and sea, according to the Times story which appeared one day before Russian Security Council Secretary Sergei Shoigu warned in an interview with TASS deployment of NATO troops in what this Russian state news agency described as “new Russian territories still controlled by Ukraine” can trigger World War III.In its revised outlook IMF expects Russia’s GDP growth to exceed that of “Advanced Economies” in 2025 (1.5% vs 1.4%), but this growth rate is significantly slower than that of “Emerging Market and Developing Economies,” (3.7%) and it will slow down to 0.9% in 2026.Harper’s: Home Front (re Ukraine)

Harper’s Magazine, April 2025

From interviews given to a researcher by six Ukrainian women in May and June of last year and provided to Harper’s Magazine. The researcher’s identity has been withheld to protect the women’s safety.

i.

I’m from Kharkiv, a big industrial center in eastern Ukraine. It had been transformed in recent years, before the war—that means good roads, flower beds, lovely parks. It’s beautiful. It hurts me to know that missiles land in different parts of the city and people die. The people of Kharkiv are very tired. They’ve lived through war for more than two years. Kharkiv has filled up with people who came from small towns that were right in the line of military action. We are very close to the stations that launch missiles. So sometimes the missiles arrive first, and only then does the siren go off. No one pays attention to it anymore. People sitting in cafés keep on sitting there; people going to work keep on going to work. It is not normal for an ordinary person not to fear an explosion. People should live in peace, should develop, should go to work, should produce some products, should rest, should bring up children. Many of our children do not go to school, because there are so many destroyed schools. In addition, it is scary to send a child to school. There are only a few schools that have good bomb shelters where children study. They have even set up classrooms in the metro. Inside the subway, the passageway from one station to another is now taken up with desks.

It’s mostly older people, women, and children who ride the metro. There are very few men. It is very rare to meet a man of draft age. Recruiters go around all the places where you can meet people, handing out notices. Markets, stores, parking lots, parks, subways, buses, bus stations. These are all places where they can hand you a draft notice. Men are in the most powerless position. Because the only thing they are allowed to do is to go to war.

ii.

My friend sent me a photograph showing a vehicle belonging to the army recruitment division stopping cars and dragging out the men and taking them away. This is done by force. We call it “stealing people.” Women try to beat them back, mothers come to the enlistment center to get their sons, they make scenes, they fight. It’s led to such consequences: attacking the military personnel who are defending us, thinking that they work for the enlistment centers.

There are horrible things. I know of a situation in which a student was asked by his teacher to come in earlier. This boy was always late, he was always getting yelled at, but this time his mother got him organized and said, “Go, at least you’ll be on time for once.” He went, they took him to war, and he was dead a week later. I don’t think it will happen in the big cities, but it happens in the small towns because they are less able to stand up for themselves, they are more subordinate to the authority of men in uniforms than city dwellers. The trouble is that some small towns already have no men left, and they have very many cemeteries, and the cemeteries are full.

iii.

We visited schools near the front line. In those areas where the line went right through a town, we had to go with the children because they were afraid to go to school. They were afraid of the military, afraid of the air strikes. We simply talked with the little kids. One time, we arrived at a school, and the head teacher, who loved us and always waited for us to come and talk with the kids, was in a very bad psychological state herself. We talked with her and learned what was wrong. The day before, there was a big air strike in the center of the town, and they saw it hit a house; she and her husband ran over to see if anyone was alive in the house, if they could help. As she was running, something squished under her foot. She shone her flashlight on it and saw that she had run atop the remains of her old schoolmate. One minute she had been talking with friends and the next she ran over the body of a friend she had known since childhood and had just been talking to. Just the thought was horrifying. This woman came to the school the next day to help us organize help for the children—but who was there to help her?

iv.

If there is a man at war in a family, that adds a burden on women. Every day is filled with fear that there will be bad news. They live under regular air raids and experience extreme emotional tension, fear, and trauma. I often think about how women will have to restore Ukraine, because we are losing men. But women are so exhausted now that they may not have the strength.

Of course, there are also women whose men are not fighting. They hide these men at home, afraid they will be drafted. The social roles change: before, the man was the breadwinner, and the woman ran the house. Now women must go to work. There are cases in which women are forced to have a third child, because men with three children are not drafted.

The war leaves a mark on the behavior and emotional state of people, and violence can appear in families where it had not existed before. Teenagers, especially girls, are more vulnerable, especially in low-income families that live near military bases.

v.

There used to be an online map that showed strikes and destruction in Luhansk. One night when I was away, I couldn’t sleep, and I kept a tablet under my pillow, on which I kept checking the situation. Suddenly I saw a strike right next door to my address. I kept trying to call my father and couldn’t reach him. For a few days I thought I would lose my mind. And then my father called, his voice was cheerful, and I said, “Papa, how are you there? What’s going on?” He said, “I’m in Petrovske.” That’s a village not far from Luhansk. He said that there was so much shelling that it was impossible to stay at home. The house that was hit, next door, was where a babushka lived. I said, “How is she?” He said, “She had made some soup and took it over to an ailing neighbor, and that saved her.” It was a miracle.

vi.

War changes people. People who should not have killed, and were not born to kill, have a completely different view now, after the war. I find it very hard to look them in the eye.

I want to go back to the life I had before, but it’s not like that and it will never be like that again, so I don’t know. Yesterday, my friend asked me what my plans are for the next couple of years, and I realized that I don’t know how to make plans. It’s enough for me that I have a plan at least for a week, for a month. This is the distance in time that I can control, I can keep, and I can manage, because everything beyond that is hard to predict. I have acquaintances who are still filled with hope, but I think my only hope is that we do not die of hatred.

April 25, 2025

Vladimir Putin Praises Late Pope Francis as ‘Defender of Humanism’

The Moscow Times, 4/21/25

Russian President Vladimir Putin on Monday praised the late Pope Francis as a “defender” of humanism and justice and lauded his efforts to foster dialogue between the Catholic and Orthodox churches.

“Pope Francis enjoyed great international respect as a devoted servant of Christian teachings, a wise religious and state leader, as well as a steadfast defender of the highest ideals of humanism and justice,” read Putin’s statement, which the Kremlin published shortly after the Vatican announced the Pope’s passing.

“Throughout his papacy, he actively promoted dialogue between the Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches, as well as constructive engagement between Russia and the Holy See,” the statement added.

“I had the honor of meeting this remarkable man on multiple occasions, and I will always cherish the warmest memories of him,” Putin wrote in the statement.

The Kremlin leader met with Pope Francis in person three times — in 2013, 2015 and 2019 — and last spoke with him by phone in December 2021, just weeks before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, according to Russian state media.

Pope Francis had repeatedly called for peace in Ukraine, although he stirred controversy last year after urging Kyiv to “raise the white flag and negotiate.” Ukrainian officials reacted to those remarks with fury, even while the Vatican insisted the words “white flag” were intended to mean a cessation of hostilities, not a surrender.

Russia’s Catholic Church announced Monday afternoon that its churches across the country would hold prayer services for the late Pope.

“Starting today, in all our churches in Russia, there will, of course, be prayers for Pope Francis. We will remember and pray here, locally,” Auxiliary Bishop of Mother of God at Moscow Nikolai Dubinin told state media.

In 2016, Francis met Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill in Cuba, marking the first-ever meeting between the heads of the two churches. The historic encounter concluded with a joint 10-page declaration, hailed at the time as a milestone in relations between the Catholic and Russian Orthodox branches of Christianity.

Andrew Korybko: What Comes Next After The US’ Withdrawal From Poland’s Rzeszow Logistics Hub For Ukraine?

By Andrew Korybko, Substack, 4/9/25

This is meant to symbolize the reduction of American military aid to Kiev, not function as the first step towards a complete withdrawal from Poland or Central & Eastern Europe as a whole.

The Pentagon announced on Monday that US forces will withdraw from Poland’s Rzeszow logistics hub for Ukraine and reposition elsewhere in the country according to (a hitherto undisclosed) plan. This was then followed the day after by NBC News reporting that Trump might soon withdraw half of the 20,000 US troops that Biden sent to Central & Eastern Europe (CEE) since 2022. According to their sources, the bulk will be pulled from Poland and Romania, the two largest countries on NATO’s eastern flank.

The Polish President, Prime Minister, and Defense Minister were all quick to claim that Monday’s repositioning doesn’t amount to nor presages a withdrawal of US forces from Poland, but speculation still swirls about Trump’s plans considering the nascent Russian–US “New Détente”. Putin requested in late 2021 that the US remove its forces from CEE so as to restore Washington’s compliance with the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act whose many violations worsened the Russian-US security dilemma.

Biden’s refusal to discuss this helped make the latest phase of the now over-decade-long Ukrainian Conflict inevitable by convincing Putin that what would soon be known as the special operation was the only way to restore the increasingly lopsided strategic balance between Russia and the US. Unlike Biden, Trump appears open to at least partial compliance with Putin’s request, which could become one among several pragmatic mutual compromises that they’re negotiating to normalize ties and end the proxy war.

It was assessed in late February that “Trump Is Unlikely To Pull All US Troops Out Of Central Europe Or Abandon NATO’s Article 5”, but he’ll probably withdraw some of them from there for redeployment to Asia in order to more muscularly contain China as part of his administration’s planned eastern pivot. There are currently around 10,000 US troops in Poland, up from approximately 4,500 before the special operation, so some could hypothetically be cut but still leave with Poland more than before 2022.

Poland’s outgoing conservative president wants as many US troops as possible, including the redeployment of some from Germany, while its incumbent liberal Prime Minister is flirting with the possibility of either relying on France to balance the US or outright pivoting towards the former. The outcome of next month’s presidential election will play a huge role in determining Polish policy in this regard and could be influenced by perceptions (accurate or not) of America abandoning Poland.

Any curtailment of US troops in Poland or the public’s belief that this is inevitable could play to the pro-European liberal candidate’s favor while an explicit confirmation of the US’ commitment to retain – let alone expand – the existing level could help the pro-American conservative and populist ones. Even if Poland’s next president is a liberal, however, the US might still be able to count on the country as its regional bastion of military and political influence if the Trump Administration plays its cards rights.

For that to happen, the US would have to retain more troops there than it had before 2022 even if some are withdrawn, ensure that this level remains above any other CEE country’s, and transfer some military technologies for joint production. The first imperative would psychologically reassure the politically Russophobic population that they won’t be abandoned, the second relates to their regional prestige, and the third would keep CEE within the US military-industrial ecosystem amidst EU competition.

This could be sufficient for counteracting the liberals’ possible plans to pivot towards France at the expense of the US’ influence or maintaining the US’ predominant position in Poland if a liberal President works with his like-minded Prime Minister to rely on France for balancing the US a bit. Even if the Trump Administration fumbles this opportunity due to a lack of vision or a fully liberal government in Poland picks fights with the US for ideological reasons, the US isn’t expected to completely dump Poland.

The vast majority of Poland’s military equipment is American, which will at the very least lead to the continued supply of spare parts and likely lay the basis for even more arms deals. US forces are also currently based in almost a dozen facilities across the country, and the advisory role that some play helps shape Poland’s outlook, strategies, and tactics during its ongoing military buildup. There’s accordingly no reason why the US would voluntarily cede such influence over what’s now NATO’s third-largest military.

As such, the most radical scenario of a full-blown liberal-led Polish pivot towards France would be limited by the impracticality of replacing American military wares with French ones anytime soon, with the furthest that this might go being the hosting of nuclear-equipped Rafale fighters. Poland could also invite some French troops into the country, including for advisory purposes, and maybe even sign a few arms deals. It won’t, however, ask US forces to leave since it wants to preserve their tripwire potential.

With the interplay of these interests in mind, it can be concluded that the US’ withdrawal from Poland’s Rzeszow logistics facility for Ukraine is meant to symbolize the reduction of American military aid to Kiev, not function as the first step towards a complete withdrawal from Poland or CEE as a whole. While some regional US troop reductions are possible as one among several pragmatic compromises that Trump might agree to with Putin for normalizing ties and ending the proxy war, a full pullout isn’t expected.

April 24, 2025

William Hartung: The New Age Militarists

By William Hartung, Consortium News, 3/20/25

Alex Karp, the CEO of the controversial military tech firm Palantir, is the coauthor of a new book, The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West.

In it, he calls for a renewed sense of national purpose and even greater cooperation between government and the tech sector. His book is, in fact, not just an account of how to spur technological innovation, but a distinctly ideological tract.

As a start, Karp roundly criticizes Silicon Valley’s focus on consumer-oriented products and events like video-sharing apps, online shopping and social media platforms, which he dismisses as “the narrow and the trivial.”

His focus instead is on what he likes to think of as innovative big-tech projects of greater social and political consequence.

He argues, in fact, that Americans face “a moment of reckoning” in which we must decide “what is this country, and for what do we stand?”

And in the process, he makes it all too clear just where he stands — in strong support of what can only be considered a new global technological arms race, fueled by close collaboration between government and industry and designed to preserve America’s “fragile geopolitical advantage over our adversaries.”

Karp believes that applying American technological expertise to building next-generation weapons systems is the genuine path to national salvation and he advocates a revival of the concept of “the West” as foundational for future freedom and collective identity.

As Sophie Hurwitz of Mother Jones noted recently, Karp summarized this view in a letter to Palantir shareholders in which he claimed that the rise of the West wasn’t due to “the superiority of its ideas or values or religion… but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence.”

Count on one thing: Karp’s approach, if adopted, will yield billions of taxpayer dollars for Palantir and its militarized Silicon Valley cohorts in their search for AI weaponry that they see as the modern equivalent of nuclear weapons and the key to beating China, America’s current great power rival.

Militarism as a Unifying Force in a New Manhattan Project

Karp may be right that this country desperately needs a new national purpose, but his proposed solution is, to put it politely, dangerously misguided.

Ominously enough, one of his primary examples of a unifying initiative worth emulating is World War II’s Manhattan Project, which produced the first atomic bombs. He sees the building of those bombs as both a supreme technological achievement and a deep source of national pride, while conveniently ignoring their world-ending potential. And he proposes embarking on a comparable effort in the realm of emerging military technologies:

“The United States and its allies abroad should without delay commit to launching a new Manhattan Project in order to retain exclusive control of the most sophisticated forms of AI for the battlefield — the targeting systems and swarms of drones and robots that will become the most powerful weapons of the century.”

And here’s a question he simply skips: How exactly will the United States and its allies “retain exclusive control” of whatever sophisticated new military technologies they develop?

The Badger nuclear explosion in 1953 at the Nevada Test Site. (Public domain, National Nuclear Security Administration / Nevada Site Office)

After all, his call for an American AI buildup echoes the views expressed by opponents of the international control of nuclear technology in the wake of the devastating atomic bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended World War II — the futile belief that the United States could maintain a permanent advantage that would cement its role as the world’s dominant military power.

Nearly 80 years later, we continue to live with an enormously costly nuclear arms race — nine countries now possess such weaponry — in which a devastating war has been avoided as much thanks to luck as design.

Meanwhile, past predictions of permanent American nuclear superiority have proven to be wishful thinking. Similarly, there’s no reason to assume that predictions of permanent superiority in AI-driven weaponry will prove any more accurate or that our world will be any safer.

Technology Will Not Save Us

Karp’s views are in sync with his fellow Silicon Valley militarists, from Palantir founder Peter Thiel to Palmer Luckey of the up-and-coming military tech firm Anduril to America’s virtual co-president, SpaceX’s Elon Musk. All of them are convinced that, at some future moment, by supplanting old-school corporate weapons makers like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, they will usher in a golden age of American global primacy grounded in ever better technology.

They see themselves as superior beings who can save this country and the world, if only the government — and ultimately, democracy itself — would get out of their way. Not surprisingly, their disdain for government does not extend to a refusal to accept billions and billions of dollars in federal contracts.

Their anti-government ideology, of course, is part of what’s motivated Musk’s drive to try to dismantle significant parts of the federal government, allegedly in the name of “efficiency.”

An actual efficiency drive would involve a careful analysis of what works and what doesn’t, which programs are essential and which aren’t, not an across-the-board, sledgehammer approach of the kind recently used to destroy the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), to the detriment of millions of people around the world who depended on its programs for access to food, clean water and health care, including measures to prevent the spread of HIV-AIDS.

Musk with President Donald Trump outside the White House, March 11. ( White House /Molly Riley, Public domain)

Internal agency memos released to the press earlier this month indicated that, absent USAID assistance, up to 166,000 children could die of malaria, 200,000 could be paralyzed with polio and a million of them wouldn’t be treated for acute malnutrition. In addition to saving lives, USAID’s programs cast America’s image in the world in a far better light than does a narrow reliance on its sprawling military footprint and undue resort to threats of force as pillars of its foreign policy.

[CN: Eighty-percent of USAID was shut down before a judge stopped it. USAID delivered coup d’etats, not just food.]

Past Miracle Weapons

As a military proposition, the idea that swarms of drones and robotic systems will prove to be the new “miracle weapons,” ensuring American global dominance, contradicts a long history of such claims.

From the “electronic battlefield” in Vietnam to President Ronald Reagan’s quest for an impenetrable “Star Wars” shield against nuclear missiles to the Gulf War’s “Revolution in Military Affairs” (centered on networked warfare and supposedly precision-guided munitions), expressions of faith in advanced technology as the way to win wars and bolster American power globally have been misplaced.

Either the technology didn’t work as advertised, adversaries came up with cheap, effective countermeasures, or the wars being fought were decided by factors like morale and knowledge of the local culture and terrain, not technological marvels. And count on this: AI weaponry will fare no better than those past “miracles.”

“They see themselves as superior beings who can save this country and the world, if only the government — and ultimately, democracy itself — would get out of their way.”

First of all, there is no guarantee that weapons based on immensely complex software won’t suffer catastrophic failure in actual war conditions, with the added risk, as military analyst Michael Klare has pointed out, of starting unnecessary conflicts or causing unintended mass slaughter.

Second, Karp’s dream of “exclusive control” of such systems by the U.S. and its allies is just that — a dream.

China, for instance, has ample resources and technical talent to join an AI arms race, with uncertain results in terms of the global balance of power or the likelihood of a disastrous U.S.-China conflict.

Third, despite Pentagon pledges that there will always be a “human being in the loop” in the use of AI-driven weaponry, the drive to wipe out enemy targets as quickly as possible will create enormous pressure to let the software, not human operators, make the decisions. As Biden administration Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall put it, “If you have a human in the loop, you will lose.”

Automated weapons will pose tremendous risks of greater civilian casualties and, because such conflicts could be waged without putting large numbers of military personnel at risk, may only increase the incentive to resort to war, regardless of the consequences for civilian populations.

What Should America Stand For?

Technology is one thing. What it’s used for, and why, is another matter. And Karp’s vision of its role seems deeply immoral. The most damning real-world example of the values Karp seeks to promote can be seen in his unwavering support for Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza.

Not only were Palantir’s systems used to accelerate the pace of the Israeli Defense Force’s murderous bombing campaign there, but Karp himself has been one of the most vocal supporters of the Israeli war effort. He went so far as to hold a Palantir board meeting in Israel just a few months into the Gaza war in an effort to goad other corporate leaders into publicly supporting Israel’s campaign of mass killing.

Are these really the values Americans want to embrace? And given his stance, is Karp in any position to lecture Americans on values and national priorities, much less how to defend them?

Despite the fact that his company is in the business of enabling devastating conflicts, his own twisted logic leads Karp to believe that Palantir and the military-tech sector are on the side of the angels. In May 2024, at the “AI Expo for National Competitiveness,” he said of the student-encampment movement for a ceasefire in Gaza, “The peace activists are war activists. We are the peace activists.”

Invasion of the Techno-Optimists

And, of course, Karp is anything but alone in promoting a new tech-driven arms race. Musk, who has been empowered to take a sledgehammer to large parts of the U.S. government and vacuum up sensitive personal information about millions of Americans, is also a major supplier of military technology to the Pentagon.

And Vice President J.D. Vance, Silicon Valley’s man in the White House, was employed, mentored and financed by Palantir founder Thiel before joining the Trump administration.

The grip of the military-tech sector on the Trump administration is virtually unprecedented in the annals of influence-peddling, beginning with Musk’s investment of an unprecedented $277 million in support of electing Donald Trump and Republican candidates for Congress in 2024.

Thiel in 2022 at an event in Scottsdale, Arizona. (Gage Skidmore / Flickr/ CC BY-SA 2.0)

His influence then carried over into the presidential transition period, when he was consulted about all manner of budgetary and organizational issues, while emerging tech gurus like Marc Andreessen of the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz became involved in interviewing candidates for sensitive positions at the Pentagon.

Today, the figure who is second-in-charge at the Pentagon, Stephen Feinberg of Cerberus Capital, has a long history of investing in military firms, including the emerging tech sector.

But by far the greatest form of influence is Musk’s wielding of the essentially self-created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to determine the fate of federal agencies, programs and employees, despite the fact that he has neither been elected to any position, nor even confirmed by Congress and that he now wields more power than all of Trump’s cabinet members combined.

As Alex Karp noted — no surprise here, of course — in a February call with Palantir investors, he’s a big fan of the DOGE, even if some people get hurt along the way:

“We love disruption, and whatever’s good for America will be good for Americans and very good for Palantir. Disruption, at the end of the day, exposes things that aren’t working. There will be ups and downs. There’s a revolution. Some people are going to get their heads cut off. We’re expecting to see really unexpected things and to win.”

Even as Musk disrupts and destroys civilian government agencies, some critics of Pentagon overspending hold out hope that at least he will put his budget-cutting skills to work on that bloated agency. But so far the plan there is simply to shift money within the department, not reduce its near-trillion-dollar top line.

And if anything is trimmed, it’s likely to involve reductions in civilian personnel, not lower spending on developing and building weaponry, which is where firms like Palantir make their money.

Musk’s harsh critique of existing systems like Lockheed’s F-35 jet fighter — which he described as “the worst military value for money in history” — is counterbalanced by his desire to get the Pentagon to spend far more on drones and other systems based on emerging (particularly AI) technologies.

Of course, any ideas about ditching older weapons systems will run up against fierce resistance in Congress, where jobs, revenues, campaign contributions and armies of well-connected lobbyists create a firewall against reducing spending on existing programs, whether they have a useful role to play or not.

And whatever DOGE suggests, Congress will have the last word. Key players like Sen. Roger Wicker have already revived the Reaganite slogan of “peace through strength” to push for an increase of — no, this is not a misprint! — $150 billion in the Pentagon’s already staggering budget over the next four years.

What Should US National Purpose Be?

Karp and his Silicon Valley colleagues are proposing a world in which government-subsidized military technology restores American global dominance and gives the U.S. a sense of renewed national purpose.

It is, in fact, a remarkably impoverished vision of what the United States should stand for at this moment in history when non-military challenges like disease, climate change, racial and economic injustice, resurgent authoritarianism and growing neo-fascist movements pose greater dangers than traditional military threats.

Technology has its place, but why not put America’s best technical minds to work creating affordable alternatives to fossil fuels, a public health system focused on the prevention of pandemics and other major outbreaks of disease and an educational system that prepares students to be engaged citizens, not just cogs in an economic machine?

Reaching such goals would require reforming or even transforming American democracy — or what’s left of it — so that the input of the public actually made far more of a difference and leadership served the public interest, not its own economic interests. In addition, government policy would no longer be distorted to meet the emotional needs of narcissistic demagogues, or to satisfy the desires of delusional tech moguls.

By all means, let Americans unite around a common purpose. But that purpose shouldn’t be a supposedly more efficient way to build killing machines in the service of an outmoded quest for global dominance. Karp’s dream of a “technological republic” armed with his AI weaponry would be one long nightmare for the rest of us.

William D. Hurtin g , a TomDispatch regular, is a senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and the author of Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex.

This article is from TomDispatch.com.

April 23, 2025

The Grayzone: ‘Independent’ anti-Russia outlet Meduza faces collapse after US funding slashed

By Kit Klarenberg, The Grayzone, 3/18/25

After fervently denying that they relied on financial support from the US government, the supposedly “independent” Russian language paper Meduza has been thrown into existential crisis following the Trump administration’s pause on foreign development assistanceAlexey Kovalev, a self-described “Russian journalist currently living in exile for fear of persecution back home,” had spent much of his career at Meduza, the leading opposition media outlet in Russia. Since leaving the paper under mysterious circumstances in the summer of 2023 and relocating to London, Kovalev has split time writing commentaries for Foreign Policy and attacking reporters at The Grayzone, whom he has falsely painted as Russian assets, while calling for their imprisonment.

“The Grayzone is Russia’s US-based disinformation laundromat,” Kovalev ranted in a July 2024 blog post. “This conspiracy blog’s founders, Aaron Mate and Max Blumenthal, help the Kremlin disseminate its false narratives in exchange for favors from a senior Russian government official Dmitry Polyansky, the country’s deputy ambassador to the UN. They act as unregistered foreign agents and should be investigated by the Department of Justice for possible FARA violations.”

“Independent” journalist Alexey Kovalev left Meduza under mysterious circumstances, and has spent much of his time since clamoring for Grayzone reporters to be persecuted by the US government.

“Independent” journalist Alexey Kovalev left Meduza under mysterious circumstances, and has spent much of his time since clamoring for Grayzone reporters to be persecuted by the US government.Nearly every word Kovalev wrote was false; The Grayzone has no financial or political relationship with the Russian government, and none of its reporters have received favors from Polyansky or any other Russian official.

Now that the self-exiled troll’s former employers at Meduza have been plunged into a financial crisis by the Trump administration’s pause on foreign development assistance, Kovalev’s smears of The Grayzone have been exposed as an exceedingly embarrassing exercise in projection.

As The New York Times reported this February 26, grants from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) reportedly accounted for 15% of the outlet’s budget. So while The Grayzone accepts no foreign state support, it turns out that Meduza can not survive for a day without a constant cash infusion from its government sponsors in Washington.

Meduza’s covert US funding was revealed in a New York Times article lamenting the Trump administration’s dramatic cuts in funding for various US-financed destabilization and regime change programs across the world. According to the Times, the cuts to USAID could potentially damage Meduza’s operations more than “cyberattacks, legal threats and even poisonings of its reporters.”

The outlet went on to note that while a handful of other Western countries like Germany and Norway “contribute to independent media,” their share is “tiny in comparison with American funding.” Simultaneously, “many traditional media supporters” – including the CIA-connected Ford Foundation, and George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, a “giant grant maker” – have “abandoned much of [their] media funding.” A Columbia University lecturer complained the Trump administration’s aid pause was “really a blood bath.”

While a 2021 investigation by The Grayzone’s Max Blumenthal revealed several grants and pledges of assistance from NATO states to Meduza, the outlet’s leadership fervently denied any suggestion of foreign sponsorship. The new revelations by the Times reveal Russia’s top opposition outlet as anything but the “independent” paper they marketed to the public.

Leaked UK files suggest Meduza’s role as NATO state-backed projectRumors about Meduza’s Western funding have swirled since its creation in October 2014, after its founder, Galina Timchenko, was fired from one of Russia’s most popular news portals for publishing an interview with the leader of Western-backed Ukrainian fascist paramilitary group, Right Sector. That same month, Meduza cofounder Ivan Kolpakov flatly refused to reveal the outlet’s funding sources in discussions with Western media:

“I can’t tell you whether those financing the Meduza Project are Russian or foreign. There’s a huge discussion about our investors among Russian journalists, with some saying we have to tell people who they are. Yes, in a fairer world we probably should, but not in Russia in 2014. We have to protect our product and we have to protect our investors.”

A leak of sensitive British Foreign Office files obtained by The Grayzone in early 2021 contained clear indications that the outlet was funded by Western governments. The documents named Meduza as one of the “specific outlets” whose “viability… as long term partners” was being assessed as part of a broader clandestine effort by London to “weaken the Russian state’s influence.” Several veteran-run contractors charged with achieving this goal named the publication as an ideal conduit for anti-Kremlin propaganda.

Chief among these shady groups was a psyop specialist firm called the Zinc Network. In confidential submissions to the British government, Zinc noted that it was “delivering audience segmentation and targeting support” to both Meduza and MediaZona, another supposedly independent outlet launched by US-funded anti-Putin provocateurs Pussy Riot. Zinc stated, “the outlets lack the expertise and tools to understand their audience profiles or consumption habits, and to therefore promote content effectively to new audiences.”

A separate submission stated Zinc Network was “supporting Russian language media outlets across Eastern Europe by developing audience growth strategies,” under the auspices of a “pioneering media development programme for USAID,” strongly indicating its cloak-and-dagger collaboration with Meduza was financed by Washington. Elsewhere, the contractor committed to providing intensely intimate assistance to all its Russian assets, including “counselling and mental health support.” This was inspired by the politically motivated June 2019 arrest of Meduza reporter Ivan Golunov, for which law enforcement officials involved were fired.

The same document also contained a pledge to “increase search ranking and visibility” of media platforms like Meduza, by teaching them search engine optimization techniques, as well as “paid search activity for priority phrases” training in order to direct people searching for the phrase “news in Russian” away from RT. Fittingly, in a dig at the Russian state broadcaster, Meduza adopted the slogan “The Real Russia, Today,” sarcastically tweaking RT’s former name.

At the time, this journalist submitted questions to Kolpakov, as well as then-Meduza investigations editor Alexey Kovalev, about the documents suggesting NATO state support for their outlet. In one email correspondence, Kovalev alleged Meduza was financed purely by online advertising revenue from “high profile clients,” supposedly even including the Kremlin itself.

Albany expressed particular interest in Meduza’s online games, which “encourage participation through social media and mobile platforms” and “embrace political themes (e.g. “Putin Bingo,” “help Putin get to his meeting with the Pope on time” and “help the Orthodox priest get to his church without succumbing to earthly pleasures”).

The contractor hoped to assist the outlet in creating more online games, “the aim [being] to create content which is good enough to have a pull effect amongst Russian-speaking youth” in Moscow’s near abroad. Ultimately, the aim was to create “satirical games” which would demonstrate the superiority of Western European culture over Russia’s, or as (they put it) that “the offer of a fairer, respectful, and caring society is better than that of an arrogant, nationalistic regime.”

It is uncertain if this British-financed sponsorship materialized. However, these disclosures led to Meduza being labelled a “foreign agent” by Russian authorities. The outlet complained that on top of being compelled to report all the website’s income and expenses to Moscow’s Justice Ministry, the classification also had the potential to damage Meduza’s advertising revenue. The label was slammed as a gross attack on independent media by Western press rights groups, and the European Union.

These days, Meduza apparently needs all the overseas financial help it can get. As the NY Times noted, Meduza was just one “of hundreds of newsrooms in dozens of countries” collectively raking in $180 million annually in funding from USAID, the State Department, and the National Endowment for Democracy to “support journalism and media development.”

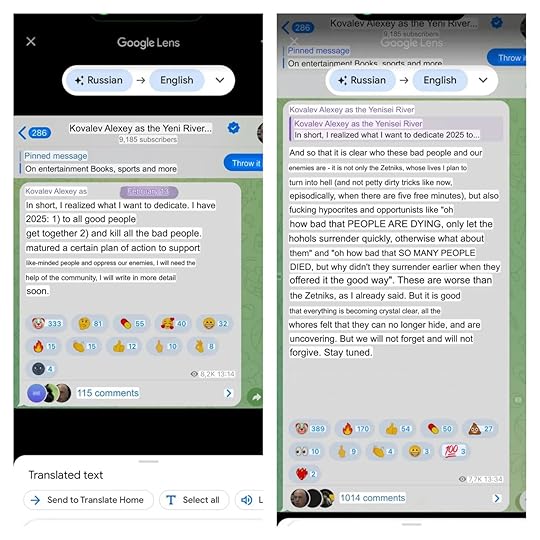

“Kill all the bad people”: diaries of a madmanWith its financial pipeline to Washington severed by the Trump administration, mass layoffs at Meduza seem inevitable. Meanwhile, after spending months falsely accusing Grayzone reporters of serving as Russian assets, the former Meduza reporter Kovalev has gradually descended into a state of apparent madness.

In a widely ridiculed Telegram post on February 13, 2025, Kovalev declared that one of his goals for 2025 was to “kill all the bad people… and oppress our enemies,” declaring, “I will need the help of the community.”

The “bad people,” he explained, were not just the Russian nationalists who follow Putin, but those among his liberal opponents who had grown weary of the Ukraine proxy war, and begun calling for a settlement to end the killing. “These are worse than the [Russian nationalists]… But it is good that it is becoming crystal clear. All the whores felt they could no longer hide, and are exposing themselves. But we will not forget and will not forgive. Stay tuned.”

Weeks later, as the lights flickered off at Meduza, Kovalev locked his Twitter/X account and continued his increasingly ravings within the confines of his digital “community.” Foreign Policy has not yet responded to a request for comment on its contributor’s call to “kill all the bad people.”

April 22, 2025

Russia Matters: West, Ukraine to Discuss Peace Plan That Offers Concessions to Russia on Wednesday

Russia Matters, 4/21/25

With the 30-hour Easter ceasefire come and gone, Western and Ukrainian officials will re-convene in London this week to discuss a confidential document that contains “ideas for how to end the war in Ukraine by granting concessions to Russia, including potential U.S. recognition of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and excluding Kyiv from joining NATO,” according to WSJ’s Michael Gordon and Alan Cullison. In the shorter-term the U.S. proposes freezing the frontline “while designating the territory around the nuclear reactor in Zaporizhzhia as neutral territory that could be under American control,” according to these two journalists. While Russia won’t be sending a representative to the April 23 talks, which will bring together U.S., Ukrainian and European officials, Vladimir Putin signaled that he is prepared to explore a partial ceasefire even as he declared the Easter truce expired. “The proposal not to strike at civilian infrastructure facilities” should be a “subject for careful study,” he told Russian media on April 21. In his remarks to Russian journalists on that day Putin also, somewhat surprisingly, acknowledged that the Easter weekend ceasefire was partially observed by the Ukrainian side.1When asked about the pending expiration of New START, Alexey Arbatov, who is one of Russia’s most renowned nuclear arms control experts (if not the most renowned), warned that the U.S. and Russia “may find ourselves on the ladder of escalation to a nuclear war, from which it is almost impossible to jump off… without the New START treaty and the numerous preceding treaties and agreements, we would now find ourselves back in the nightmare days of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.” While New START cannot be extended as it is, the signatories could adopt “politically binding statements that the parties will not exceed the New START ceilings,” according to Arbatov. “There is another, more formal option. It is possible to use Article 15 of the New START Treaty and amend it to allow for its agreed extension for a five-year period more than once,” he proposed. In the meantime Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov expressed doubts Russia needs a replacement for New START, at least for as long as the relationship with the U.S. is adversarial. “Americans… continue to label us an adversary… You can’t just cherry-pick one element from the New START Treaty—like the right to inspect each other’s nuclear facilities—and ignore the rest,” he asserted.CSIS’s dive into China-Russia military ties not only explores heavily-sanctioned Russia’s increasing dependence on China for supplies of “critical defense components,” but also reveals a shift in leadership roles in RF-PRC wargames. “As China’s military capabilities grow, CSIS analysts highlight a shift in leadership within joint drills—such as the 2021 Zapad/Interaction exercise where China led operations—signaling a potential role reversal with China as the senior partner in future engagements,” according to this U.S. think-tank’s April 2025 report, entitled “How Deep Are China-Russia Military Ties?”Zelensky speaks of ‘hatred of Russians’

Global Village Space, 3/28/25

In an interview with the French daily Le Figaro published on Wednesday [late March 2025], Zelensky identified the emotion as one of his three key psychological drivers since the escalation of the conflict in February 2022.

Zelensky said he hated “Russians who killed so many Ukrainian citizens,” adding that he considered such an attitude appropriate in wartime. His other motivations included a sense of national dignity and the desire for his descendants to live “in the free world.”

Ukrainian officials have accused Russia of being a historic oppressor while Zelensky has previously touted Ukrainians’ “love of freedom” as a trait that distinguishes them from Russians.

Zelensky, whose presidential term expired last year, was elected in 2019 on a platform of defusing tensions with Moscow and reconciling ethnic Russian Ukrainians in Donbass, many of whom opposed the 2014 Western-backed coup in Kiev. However, his initial diplomatic efforts were thwarted by radical Ukrainian nationalists in the body politic.

Since the coup, Kiev has enacted various policies undermining the rights of ethnic minorities, with Russians as the primary target. Moscow has accused Zelensky of intensifying the crackdown, particularly by attacking the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the country’s largest religious denomination, which now faces potential prohibition for having historic links with Russia.

In a recent interview, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov asserted that Zelensky caters to “the segment of the population that holds radical, ultra-right, revanchist, Banderite views,” as his image as a national leader increasingly deteriorates.

“Zelensky does not want to display weakness, as he realizes that his days are numbered,” the Russian official claimed.

April 21, 2025

In Ukraine, Ultra-Nationalists Are the ‘Good Guys’ – My Interview with Ukrainian Academic Marta Havryshko

By Natylie Baldwin, Consortium News, 4/21/25

Neo-Nazism’s rise in Ukraine is due to the silent approval of Ukraine’s political and military elites who prefer to turn a blind eye because they rely on the far-right for their military potential, Ukrainian academic Marta Havryshko tells Natylie Baldwin.

Dr. Marta Havryshko holds a Ph.D. in History from the Ivan Franko National University in Lviv, Ukraine. Her research interests are primarily focused on sexual violence during World War II and the Holocaust, women’s history, feminism, and nationalism.

She is currently a visiting assistant professor at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Her Twitter handle is @HavryshkoMarta.

I spoke with her recently via email.

Baldwin: Please tell us a bit about your academic background and how you came to focus on the holocaust and Ukrainian ultra-nationalism?

Havryshko: Ukrainian ultra-nationalism is something that has surrounded me since childhood. I grew up in a village in Galicia, a region that holds a special place in the history of the Ukrainian nationalist underground, as it was here that the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), founded in 1929, and its military wing — the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which emerged in 1942 — were especially active.

Some of my relatives were involved in these organizations and were later repressed by the Soviet regime for their participation. Family memory was saturated with stories of forced collectivization.

No family gathering passed without my grandfather recounting how the Soviets took away his family’s oxen, and how, when those oxen were later driven past their house to pasture, they made sorrowful sounds. Actually, the land, where my parents erected a house in [the] 2000s long ago belonged to our family and was seized by Soviets in 1939, when they occupied Western Ukraine due to [the] Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Despite the ethnic diversity in my family, the stories centered on the Ukrainian one were dominant. I believe this was partly due to it being a survival strategy in a small Galician community, which had various instruments of social control —including over the hegemonic memory regime. My school was one such guardian of the “correct” national memory.

The history of Ukrainian nationalism was taught as both heroic and tragic, with a clear division between the “good guys” (Ukrainian nationalists) and the “bad guys” (Soviets). War crimes and crimes against humanity committed by OUN and UPA were obscured, marginalized, and silenced in the educational program. The glorification of these organizations became a fundamental part of “patriotic upbringing” at my school. That is why, to this day, I know all the nationalist songs by heart.

When I became a history student at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, I didn’t significantly deepen my knowledge about OUN and UPA, as an apologetic approach to them prevailed in the academic environment. So, after defending my dissertation on the attitudes of various Galician political circles toward Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1939, I decided to delve deeper into the history of Ukrainian nationalism during WWII. My findings shocked me.

I realized that many of those who are celebrated in Ukraine as freedom fighters were, in fact, involved in the Nazi Holocaust and anti-Jewish violence. The myth that Jews willingly served in the UPA shattered when I started conducting interviews with my informants—dozens of women who had been part of the OUN underground.

One lady told me there was a Jewish doctor in her UPA unit, but he was always under guard. “Why?” I asked. “So he wouldn’t escape,” she replied, surprised by my ‘naivety’. This story — like many others I heard — revealed the forced mobilization of Jewish professionals into the ranks of the UPA. Some of them were executed in the spring of 1944, as they were suspected of potentially siding with the Soviets.

Baldwin: You’ve written a lot about how the history of WWII and how the holocaust has been weaponized by both Russia and Ukraine in the current conflict. Can you explain what you see as the misuse of the holocaust and WWII by the Russian government and nationalists?

Havryshko: The memory of World War II plays a crucial role in the political and military discourse of the Russian-Ukrainian war. And not only because it is the largest war in Europe since 1945. And not only because there are still living witnesses of the Nazi occupation in Ukraine, who often compare the behavior of the Nazis to that of Russian soldiers in the occupied Ukrainian territories.

The memory of World War II is weaponized by different political actors for political and military purposes. For example, when Putin began his angry speech on the night of February 24, 2022, he emphasized that one of the goals of the so-called “special military operation” was the “denazification” of Ukraine.

Top Russian propagandists frequently refer to the Ukrainian government as a “Nazi regime” and call Ukrainian soldiers “Nazis.” State actors construct a hegemonic narrative that evokes the memory of the brave Soviet people, particularly Russians, who fought against the Nazis and their allies. This idea is clearly represented in the so-called Immortal Regiment marches held in major Russian cities every May 9 during Victory Day celebrations.

During these processions, people carry portraits of their ancestors who fought in the “Great Patriotic War.” Since 2022, participants in some of these events have also begun carrying portraits of Russian soldiers who died in the war against Ukraine—portraying them as the successors of their grandfathers who fought the Nazis.

Russian soldiers participating in the war against Ukraine also wear symbols and patches that allude to WWII memory—for example, the ribbon of Saint George. In Ukraine, the opposite trend is observed. Some Ukrainian soldiers wear patches bearing the symbol of the Waffen-SS Division “Galicia,” formed in 1943 under German command.

There is also a unit in the Ukrainian army named “Nachtigall,” after the battalion formed by the German Abwehr in 1941 from ethnic Ukrainians. Another unit named Luftwaffe uses Nazi eagle as its symbol.

The “Vedmedi” unit uses SS bolts and the SS motto “My Honor is Loyalty” as official insignia. Some soldiers also wear patches featuring symbols of various SS divisions, including infamous Dirlewanger Brigade, and the Nazi eagle. Some soldiers of the Russian Volunteer Corps wear ROA patches (Russian Liberation Army, aligned with Nazi Germany).

A number of soldiers have even founded clothing brands that glorify the Wehrmacht and de facto justify Nazi crimes, including the Holocaust.

This trend is deeply absurd, given that the Nazi occupation regime in Ukraine led to the deaths of millions of people, including 1.5 million Jews. However, in the logic of those soldiers who glorify the army of the Third Reich, the Nazis fought against the main enemy of the Ukrainian nation — the Russians and the Soviet Union.

In doing so, they artificially isolate this particular aspect of Nazism, while ignoring its crimes. This is an extremely dangerous trend that, unfortunately, is gaining popularity, due to the silent approval of Ukraine’s political and military elites, which prefer to turn a blind eye on this because they rely on the far-right in terms of their military potential.

Baldwin: Can you also explain how the Ukrainian government and its western allies have white-washed the contemporary Ukrainian ultra-nationalists and their historical role in the WWII massacres against Jews, Poles and others?

Havryshko: For a long time after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the glorification of OUN and UPA remained mostly a regional cult, specific to Western Ukraine. After the Maidan revolution, this cult began to be artificially promoted at the national level.

Firstly, this was facilitated by the creation of the so-called Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, which made the glorification of Ukrainian nationalists one of its key areas of work. Secondly, the Ukrainian parliament adopted a memorial law in 2015 that recognized members of the OUN and UPA as “fighters for the independence of Ukraine” and introduced penalties for individuals who “publicly express disrespect” toward them.

A number of Western scholars criticized this law, fearing that it would close the door to open discussion about the complex history of the OUN and UPA.

Despite this, both state and non-state memory actors in Ukraine launched a vigorous campaign to heroize Ukrainian nationalists. This was reflected in the emergence of numerous new places of memory — such as monuments, museums, memorial plaques, street names, exhibitions, documentary films, programs, etc. At the same time, a process of so-called “decommunization” began, aimed at erasing everything connected to Ukraine’s Soviet past from the public space.

This memory crusade targeted not only monuments to Lenin, Dzerzhinsky, Kosior, and other Soviet figures involved in mass repressions and other Soviet crimes, but also soldiers of the Red Army who liberated Ukraine from German occupation. This war on everything Soviet entered a new phase after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

One of its consequences has been an even deeper “Banderization” of Ukraine (from Stepan Bandera—the leader of the OUN). Streets named after Stepan Bandera and UPA commander Roman Shukhevych began to appear in regions like Chernihiv, Odesa, Kherson, Donetsk, and Poltava — places where these historical figures were never popular, and were often seen as Nazi collaborators responsible for political terror against Ukrainians who had built the “Soviet national project” in Ukraine.

The problem with this memorialization lies in the fact that Bandera, Shukhevych, and other members of the OUN and UPA were proponents of ethnic nationalism, racism, and antisemitism and an authoritarian state. They collaborated with the Nazis and took part in their crimes, including the Holocaust.

Furthermore, they are responsible for the deaths of at least 100,000 Polish civilians in Ukraine during World War II as part of their nationalist project to build an ethnically homogeneous state.

They also widely used terror against Ukrainian civilians who criticized their actions. They often applied the principle of collective punishment, killing entire families—including small children—of alleged “enemies of the Ukrainian nation.”

However, these inconvenient facts are being concealed, and those who criticize this ethnonationalist memory regime are labeled “Russian agents”—a charge which, in the context of war with Russia, not only delegitimizes them but effectively puts a target on their backs.

They are subjected to cancel culture, bullied by their colleagues, and their voices are silenced and marginalized. This is being done because a heroic historical myth is needed by the state to consolidate society around political leadership during wartime. In other words, the state is instrumentalizing historical myths and nationalist memory in its war efforts.

What is particularly notable is that Western scholars, who were until recently quite critical of the glorification of the OUN and UPA, are now largely silent. Moreover, some are framing this ethnonationalist memorial policy as part of the nation-building process and decolonization.

In doing so, they are legitimizing dangerous trends—glorification of ethnonationalism, racism, antisemitism, and the justification of ethnic and political violence in the name of the nation. This poses a threat to a Ukrainian democratic future and clearly contradicts talking points that Ukraine is fighting for “freedom and democracy” in its resistance to Russian aggression.

Baldwin: There have been many reports in recent years about the growing influence of ultranationalists on Ukrainian society and culture. For example, there are reports of Ukrainian schoolbooks that teach outlandish propaganda, such as suggesting that Ukraine was the linguistic origin of western European languages and revering Nazi era war criminals. As far as you are aware, to what extent is there such propaganda in Ukrainian schools? What does this portend for the future of Ukrainian society?

Havryshko: The whitewashing of the Ukrainian nationalist underground—which inevitably leads to Nazi apologism and Holocaust distortion—is one of the most troubling developments in public schools across Ukraine. For example, not long ago, all schools in Lviv, following an order from the city council, widely commemorated the anniversary of the death of Roman Shukhevych, who was killed by the Soviets on March 5, 1950. Children of various ages watched propaganda films and attended lectures. The youngest students were encouraged to draw the red-and-black flag of the UPA or portraits of Shukhevych. These forms of memorialization were clearly apologetic. I highly doubt that the children were offered any opportunity to discuss the role of the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion, which Shukhevych commanded during punitive actions against civilians in Belarus in 1942, or his responsibility for other war crimes.

Any attempts to include critical questions about the history of the OUN and UPA in Ukrainian school textbooks are met with strong resistance from nationalist circles. A few years ago, for instance, a scandal broke out in Lviv when a history textbook referred to the “Nachtigall” Battalion as a collaborationist formation—which it indeed was, since it was created by the Germans and served German interests.

The anti-Jewish violence committed by Ukrainian nationalists is one of the most hidden and suppressed chapters in the school curriculum. Recently, I came across a 10th-grade history textbook published in 2023. It contained no information at all about the pogroms that took place in Western Ukraine in the summer of 1941. In many places, these pogroms occurred during a power vacuum—after the Soviet army had retreated and before the Germans had fully arrived.

Taking advantage of this vacuum, members of the OUN in towns and villages across Galicia, Bukovyna, and Volyn organized killings, beatings, rapes, and robberies of their Jewish neighbors—accusing them collectively of crimes of the Soviet regime and declaring them enemies of the Ukrainian people.

In cities like Lviv, Ternopil, and Zolochiv, these pogroms were instigated by the Germans, but local Ukrainians were willing perpetrators. This uncomfortable truth is hidden from students because it does not fit into the dominant heroic or victimhood narrative. However, responsibility can only be cultivated through the acknowledgment of one’s own guilt.

Baldwin: You have spoken frequently on social media recently about the dangerous influence of and threats you’ve personally received by Ukrainian ultranationalists and Neo-Nazis. Tell us about that. What do you think will happen with this element as the war winds down eventually and ends? Are you safe from the threats?

Havryshko: I began receiving a violent pushback from radical nationalists more than ten years ago, when I first started writing about sexual violence committed by members of the OUN and UPA—both against their female counterparts and against civilian women as a form of punishment, terror and revenge.

At that time, the leadership of the academic institution in Lviv where I worked contacted the Security Service of Ukraine to report my “dangerous activities.” The entire situation was absurd and grotesque, because I was being harassed not just by fringe far-right groups, but also by professors holding high academic positions. That was also the first time I experienced antisemitic verbal attacks that invoked a common trope about the alleged disloyalty of Jews to the Ukrainian national project.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, these attacks became more frequent. The attackers grew more aggressive, believing that by doing so they were “defending Ukraine.” In September 2023, amid the scandal surrounding Yaroslav Hunka, a former member of the Waffen-SS Galicia Division who was given standing ovations in Canadian parliament, one of Ukraine’s largest museums—the Museum of the History of Kyiv—opened a photo exhibition organized by Azov’s 3rd Assault Brigade.

The exhibit included several photos of soldiers from the Waffen-SS Galicia Division. None of the Ukrainian historians, journalists, human rights activists, cultural figures or politicians who visited the exhibition publicly commented on the inappropriateness of this kind of analogy, where active-duty members of the Ukrainian Armed Forces were essentially equating themselves with Nazi collaborators, involved in war crimes in Poland and Slovakia.

I wrote a short critical social media post about this. In response, far-right —including members of the Azov movement—launched a campaign of harassment against me. This included media publications, YouTube programs, and incitement of violence against me on the social media pages of prominent leaders of far-right groups and military units.

Students from Ivan Franko National University of Lviv even wrote a letter to the Minister of Education and Science demanding that “measures be taken” against me. I was relieved that I wasn’t in Ukraine at the time, because I honestly cannot imagine what might have happened to me.

At the same time, I began to pay closer attention to Nazi apologism in Ukraine’s wartime society—particularly within the military. And the more I study this phenomenon, the more shocked I am by its scale—and the more death and rape threats I receive from various far-right groups.

What is especially alarming is that I now receive threats not only from Ukrainian neo-Nazis, but also from foreign ones who are fighting on Ukraine’s side and are part of far-right military units such as the 3rd Assault Brigade, Karpatska Sich, Kraken, the Russian Volunteer Corps, and others.

One of those threatening me is an American neo-Nazi, antisemite, and convicted felon currently fighting in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government is instrumentalizing far-right extremists from around the world due to a shortage of manpower. Their activities are often overseen by Military Intelligence, headed by [Kyrylo Oleksiiovych] Budanov. With that kind of backing, they feel—and in fact are—truly empowered. So I cannot realistically expect protection from the Ukrainian state.

To be honest, I am afraid to travel to Ukraine due to these ongoing threats, which are laced with antisemitic slurs and misogyny. What makes the fear even more real is that last year in my hometown of Lviv, Professor Iryna Farion was shot dead. She had openly criticized right-wing soldiers for using the Russian language.

Various far-right social media channels demonized her and openly incited violence against her. According to the police, some of these channels were followed by the suspected killer, who has been detained and is under investigation.

What saddens me the most is that some of my fellow scholars in Ukraine have also threatened me, incited far-right violence against me, and downplayed or completely disregarded my concerns for my safety and the safety of my child. I have repeatedly and publicly asked them to reconsider their aggressive rhetoric, but to no avail.

Baldwin: You have talked about how the Maidan events of 2014 marked a turning point in the influence of the ultranationalists in Ukraine. In an interview with Ondrej Belecik last December, you said “I’m convinced that the Maidan Revolution enabled ultranationalists to hijack memory politics in Ukraine. They started to impose an ultranationalist narrative. And from the beginning many people were actually not in favor of this.” Can you elaborate on this? How and why do you think this hijacking was allowed to happen?

Although people with a wide range of political views took part in the Maidan protests, nationalist groups—particularly those representing the Western Ukrainian strain of nationalism historically associated with the OUN and UPA—played a significant role.

The Maidan gained enormous popularity in Western Ukraine, where then-President Viktor Yanukovych was widely perceived as overtly pro-Russian and as someone obstructing Ukraine’s movement toward the West. In contrast, in the East and South of the country, the majority of the population supported Yanukovych and held a critical view of the Maidan, which partly explains the bloody civil unrest in Donbass that started in spring 2014, that was instrumentalized by Russia.

Given that many Maidan participants were from Western Ukraine, they used specific historical analogies to legitimize their activities. In particular, they glorified Stepan Bandera, Roman Shukhevych, and used the symbols of the OUN and UPA.

In doing so, they created a symbolic connection between themselves and members of the nationalist underground through the idea of a shared struggle against a “common enemy”—Moscow. It was the radical Ukrainian nationalists from Right Sector and Patriot of Ukraine (the forerunner of Azov) who ultimately determined the fate of the Maidan by taking up arms and resorting to violence.

The victory of the Maidan thus marked the triumph of an ethnonationalist project, rather than an inclusive national one—as many Ukrainians and some Western scholars, including Americans, tried to portray it. With each passing year, this romanticized version of the Maidan is increasingly challenged by a harsher reality—one marked by attacks on the rights of Russian-speaking Ukrainians and on the Ukrainian Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate.

In this reality, the memory of millions of Ukrainians who fought against the Nazis as part of the Red Army and Soviet partisan units is being erased, and in their place stand a few dozen members of the OUN and UPA, who were not only a regional phenomenon but also collaborators with the Nazis and participants in their crimes.

In this post-Maidan reality, the memory wars have even reached major cultural figures such as Mikhail Bulgakov, Isaac Babel, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Pyotr Tchaikovsky — who have been targeted for their alleged pro-Russian positions.

Baldwin: In a May 2022 interview with Regina Muhlhauser, you discussed the role of sexual violence in the Russian-Ukrainian war. You talked about sexual violence against Ukrainian refugees who’d fled the war and were in the border countries. Can you tell us about that?

In early March 2022, shortly after the start of Russian full-scale invasion, I fled Ukraine with my 9-year-old son. We spent several hours on the Polish side of the border, waiting for our friend who was supposed to drive us both to Warsaw. During that time, I observed how some Polish men offered shelter exclusively to young women. It was unsettling.

Later, my friend—who was working with Ukrainian refugees at the border and in shelters—confirmed my suspicions. She said there was a noticeable group of men who clearly preferred to help young women, likely expecting sexual favors in return. Soon after, more and more stories began to emerge about the sexual harassment and exploitation of these vulnerable women. This issue was reflected in the reports of different human rights organizations.

Feminist friends of mine in Switzerland and Germany also confirmed that the number of Ukrainian refugees involved in prostitution in their countries is growing—particularly in street prostitution, where the most vulnerable women tend to end up. This once again proves that prostitution often becomes a “choice without a choice” for traumatized and vulnerable women. In some cases, we may be talking about sex trafficking and sexual slavery.

Baldwin: What kinds of sexual violence are we seeing in this war? Does it seem to be characterized mostly by discrete incidents on both sides or is there any evidence that it is ordered at the top levels as a policy on either side?

Sexual violence has emerged as a recurrent and disturbing phenomenon in the context of the Russian-Ukrainian war. While its presence has been documented since 2014, it has gained greater visibility and public attention following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. However, the true scope and prevalence of this violence remain largely unknown due to several structural and political constraints.

One of the most significant limitations is the lack of access to approximately 20% of Ukrainian territory currently under Russian occupation, which prevents both systematic documentation and independent research.