Natylie Baldwin's Blog, page 10

August 9, 2025

Jeff Childers: AG Orders Grand Jury Probe into Obama Officials Over Russiagate

As to whether arrests will actually occur…I’ll believe it when I see it. – Natylie

By Jeff Childers, Substack, 8/5/25

Jeff Childers is an attorney and conservative commentator.

Yesterday (August 4), CNN ran a massively encouraging story headlined, “Attorney General Bondi orders prosecutors to start grand jury probe into Obama officials over Russia investigation.”. Also yesterday, John Solomon’s Just the News ran a similar breaking story headlined, “Bondi orders evidence sent to grand jury for Russia collusion hoax.”

According to Just The News, “multiple sources” have said Attorney General Pam Bondi has now ordered evidence from the Russia collusion hoax to be sent to a federal grand jury, “probably” in Florida. Where the Mar-a-Lago raid occurred. CNN said, “a source familiar with the matter” had told them.

When the Department of Justice sends evidence to a grand jury, it’s not for show—it’s a formal step toward criminal charges. Grand juries aren’t investigative committees or cable news panels. They’re made up of everyday citizens who review evidence in secret and decide whether there’s enough to indict. And they almost always do, leading to that old saw about ham sandwiches.

The grand jury standard is low. It doesn’t require proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt; it’s just “probable cause.” So when Bondi sends the RussiaGate evidence to a grand jury, it’s a sign that indictments are not just possible. They are likely. If true, this isn’t just a narrative-management exercise anymore. It’s a real legal proceeding with bloodstained claws.

Indictments precede arrests and prosecution. Once a grand jury returns an indictment, the DOJ typically issues a warrant, and unless the charges are sealed for tactical reasons, the next step is an arrest. In federal cases, this process is usually swift and serious: U.S. Marshals or federal agents either pick the person up or notify them to surrender. An indictment means the government believes it can prove its case in court, and it isn’t just sending a message—it’s preparing to put someone in handcuffs.

Grand juries are sequestered and conducted in secret. It’s entirely possible that this grand jury is already empaneled and hearing evidence, and we wouldn’t know it. If Bondi’s team is leaking about the existence of the grand jury, then it seems more likely the grand jury was empaneled weeks or months ago, quietly receiving documents, hearing testimony, and is getting ready to hand down charges.

It’s worth repeating: you don’t leak the existence of a grand jury unless you’re nearly finished. First, because it alerts the enemy. The moment a grand jury becomes public knowledge, anyone with something to lose starts looking for the jurors, to influence, intimidate, or discredit them. Second, because if the grand jury hears your case and refuses to indict, you look like a moron. In other words, you look both politically motivated and legally incompetent.

Prosecutors never voluntarily take that risk unless they’re confident in what’s coming next. Assuming the leaks came from Bondi’s DOJ —and that seems almost self-evident— they know what they’re doing.

In other words, based on what we can already see —the disclosures, the criminal referrals, the grand jury order, the sudden public confirmation— we could be getting very close to high-profile arrests. Possibly within days. And based on the rapid acceleration of events over the past two weeks, it could conceivably happen this week.

The Hunt for Red August appears to be underway.

August 8, 2025

Russia Matters – Bloomberg: US, Russia Working on Deal That Would ‘Cement’ RF Gains in Ukraine

Russia Matters, 8/8/25

Following talks between Donald Trump’s envoy Steve Witkoff and Vladimir Putin this week U.S. and Russian officials are working toward an agreement on Ukrainian territories for a planned summit between the U.S. and Russian leaders that could occur as early as the next week, according to Bloomberg. The agreement aims essentially to freeze the war, cementing Putin’s land gains, and pave the way for a ceasefire and technical talks on a definitive peace settlement, “people familiar with the matter” told this news agency. Under the terms of the deal, Russia would halt its offensive in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions of Ukraine along the current battlelines. In exchange Putin is demanding that Ukraine cede entire Donbas to Russia as well as Crimea in what would require Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to order a withdrawal of troops from parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions still held by Kyiv, according to the agency. Speaking in the late afternoon of Aug. 8, Trump confirmed that the deal would involve territorial concessions. Trump said discussions were under way to get “some” land back as well as “some swapping of territories to the betterment of both,” according to Financial Times . He said the conflict could be resolved “very soon.” While having lost 99% of the Luhansk Oblast, with only 103 square miles remaining under their control in that province, Ukrainian forces continued to control some 25% of the Donetsk Oblast (2,509 square miles or 6,500 square kilometers), according to ISW’ s latest estimates.1 Forcing Ukrainian armed forces to quickly cede more than 2,600 square miles of territory they still control in Donbas, which comprises the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, without putting up a fight could be a tall order. A voluntary surrender of these territories by Ukrainians would require concessions on other issues by Russia, but, according to the Bloomberg story, it remains unclear if Moscow is prepared to give up any land that it currently occupies.*In the period of July 8–Aug. 5, 2025, Russian forces gained 226 square miles of Ukrainian territory, which is more than the 190 square miles gained by Russia in the period of June 10–July 8, 2025. However, if one were to compare shorter periods, such as the past week to the preceding week, then such a comparison would reveal that Russia’s weekly gains declined. Russia gained 31 square miles of Ukrainian territory (about 1½ Manhattan islands) over the past week (July 29–Aug. 5, 2025)—slowing to just one third the rate of the previous week’s (July 22–29, 2025) gain of 105 square miles, according to the Aug. 6, 2025, issue of the Russia-Ukraine War Report Card . Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi is warning that Russia is accelerating troop mobilization, aiming to form 10 new divisions by year’s end and adding about 9,000 troops monthly—despite suffering over 33,200 losses in July, Kyiv Independent reported. Syrskyi said Ukraine has no other option but to ramp up its own mobilization, improve training and strengthen drone capabilities to prevent Russia from achieving its objectives. Meanwhile, the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces has assured Putin that the Ukrainian front will crumble in two or three months, one source close to Russian government told Reuters .More than three years into the war, Ukrainians’ support for continuing the fight against Russia until victory is “collapsing,” according to Gallup’s interpretation of its latest poll on the subject. Indeed, the share of those who think Ukraine should continue fighting until it wins plummeted from 73% in 2022 to 24% in 2025, which represents a decline of more than 67%, according to this international pollster. In the meantime, the share of Ukrainians who think Ukraine should seek to negotiate an end to the war as soon as possible went from 22% to 69%, exceeding that of Russians (63%) who would like to see a negotiated end to the fighting.2The Russian Finance Ministry said this week that the country’s budget deficit has reached 4.88 trillion rubles ($61.1 billion) between January and July, or 2.2% of GDP, according to The Moscow Times. That is well above the 3.8 trillion rubles planned for all of 2025, according to this newspaper. The ministry blamed weaker oil and gas revenues—down nearly 19% year-on-year—and “advance financing” of expenses early in the year, the newspaper reported. Indeed, Russia’s combined oil and gas revenue totaled 787.3 billion rubles in July, down by 27%, according to the Bloomberg. Analysts, however, told MT that the real driver of the budget deficit is runaway spending.How the U.S. Air Force general in charge of nuclear missiles almost wrecked relations with the Russians in 2013

Good grief, were our government officials and military representatives this unprofessional during the Cold War? This sounds like some cringey comedic movie. – Natylie

By David Axe & Matthew Gault, Substack, 7/21/25

David Axe is a journalist and filmmaker in South Carolina.

For five days in mid-July 2013, a delegation of the Pentagon’s top nuclear officials led by U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. Michael Carey traveled to Moscow to meet its counterparts in the Russian nuke force.

It was a make-nice involving the world’s biggest atomic powers, which for decades have possessed, and held back, the power to obliterate each other and the rest of the world in mere minutes.

And it came during what was, in retrospect, the last period of potentially fruitful interactions between the Americans and Russians, as Russia would invade Ukraine just seven months later.

Carey’s meeting was, in other words, a big freaking deal.

But to Carey—at the time the head of the 20th Air Force, America’s main nuclear ICBM strike force, with 9,600 airmen and 450 continent-blasting Minuteman missiles—it was a chance to engage in an epic, ego-fueled, taxpayer-funded bender.

Over the course of the five days, Carey allegedly guzzled around 50 drinks, hit on four different women—including three he later claimed might be Russian agents—and managed to repeatedly offend his Russian military hosts.

After an investigation, Carey was removed from command and assigned as a special assistant to the commander of the Air Force’s Space Command—a position with no real power. He retired in 2014 after doing his damnedest to wreck relations between the world’s top atomic powers while in the pursuit of booze and babes.

Carey’s marathon international insult was documented in a hilarious official report obtained by The Washington Post. Let’s count the drinks that disarmed the man once in charge of America’s nuclear arsenal.

Carey in a more sober time. U.S. Air Force photoDay 1: 2 glasses of wine, at least 2 beers

Carey in a more sober time. U.S. Air Force photoDay 1: 2 glasses of wine, at least 2 beersWeather delayed Carey’s trip from his headquarters in Wyoming to Washington, D.C. for onward travel to Moscow. He had only a few hours to rest in a local hotel before meeting his five-person delegation at Dulles airport on July 14.

Carey’s crew included representatives from the Pentagon’s joint staff, U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s office, the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the organization in charge of eliminating the world’s weapons of mass destruction.

Despite the esteemed company, Carey—apparently exhausted before even stepping onto the plane—was on his worst behavior. On the first leg of the flight he drank two glasses of wine and, delayed again in Zurich, chased the wine with at least two beers.

According to a witness, the general was “visibly agitated about the long delay at Zurich, he appeared drunk and, in the public area, talked loudly about the importance of his position as commander of the only operational nuclear force in the world and that he saves the world from war every day.”

But Carey was just pre-gaming before the big binge.

U.S. airmen toast a Russian general at a Moscow air show. U.S. Air Force photoDay 2: at least 4 beers plus 2 or more other drinks

U.S. airmen toast a Russian general at a Moscow air show. U.S. Air Force photoDay 2: at least 4 beers plus 2 or more other drinksThe delegation checked into a Moscow Marriott the evening of July 15. First order of business was a team meeting to discuss the trip itinerary, including two days of meetings with Russian nuclear troops. At the meeting, Carey drank several beers … and began mouthing off.

“Again, he started in on the very loud discussions about being in charge of the only operationally deployed force and saving the world,” said a delegation member. Carey complained that his airmen had the worst morale in the Air Force—and blamed his superiors for “not helping out.”

The gripe did not include any classified information. But the witness described it as “not really something I was comfortable with you know, being part of in a Russian hotel in the middle of Moscow.”

Carey, who by this point had apparently slept only fitfully for several days running, went to the hotel lobby with one of his teammates, grabbed another beer and bought a cigar from a woman vendor. The male teammate proposed checking out a rooftop bar at the Ritz Carlton—a neighboring hotel—the next day.

But Carey suggested they go that night, and his colleague agreed.

At the rooftop bar, Carey had at least two more drinks. He and the other man met two young women who claimed to be British travel agents. The four revelers closed down the bar then wandered to the La Cantina Mexican restaurant, but it was shuttered for the night. Carey’s teammate mentioned that the Americans might go back to the Mexican joint the next day—and the girls should meet them there.

On return to America, Carey would voluntarily turn in the girls’ business cards to Air Force investigators, along with the cigar vendor’s card. The general would claim that the women’s behavior was fishy, and imply they might have been Russian agents. But Carey’s suspicion did not stop him from continuing to drink with the ladies in Moscow.

La Cantina. Virtualtourist.com photoDay 3: 9 vodka shots, a bottle of vodka & a bar crawl

La Cantina. Virtualtourist.com photoDay 3: 9 vodka shots, a bottle of vodka & a bar crawlJuly 16 was the first day of meetings with Russian troops. And boy howdy was it a boozy one. Carey was 45 minutes late meeting the rest of the team, plus some Russian military guides, waiting in the Marriott lobby.

The Russians had arranged a demonstration by nuclear-force trainees and were worried the Americans might miss it.

Carey had gotten just few hours of sleep and his eyes were bloodshot. He snoozed on the van ride to the Russian base but was still not at his best during the morning’s briefings. Claiming he could not understand the Russians’ military interpreter—described as an “attractive” young woman—Carey told one of his Russian-speaking teammates to take over the translating.

The Russians “were insulted … they were unhappy,” a witness said.

Some Russian trainees—apparently part of the Kremlin’s nuclear security force—showed off their fighting, first aid and vehicle maintenance skills. Addressing the Americans, Carey derided the demonstration as “sophomoric.”

Lunch was served in a tent near the training range. There were nine vodka toasts. Some of the Russians, including a general, sipped water instead. The Russian general, for one, said he needed to be sober since he was in charge. In an ill-conceived attempt to ape the Russians’ toasting conventions, Carey singled out the woman linguist he had previously insulted, raised his glass to her and called her “beautiful.”

Carey was drunk, according to the other Americans. He ran his mouth about the Syrian war — over which Washington and Moscow have serious disagreements—and also about National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden, who was granted asylum in Russia.

One witness reported that “at some point he announced that the reason he had been late [that] morning was that he had met two hot women at the bar the night before.” The Russians were less than thrilled about this and “made it very clear we had to be on time the next day.”

That afternoon and evening, the Americans visited a monastery and then Red Square. There was more drinking in the van. At the monastery, Carey insulted the tour guide, a woman. “At one point he tried to give her a fist bump. She had no idea what he was trying to do,” one American said.

Carey wandered away from the main group. That evening, the nearly incapacitated general couldn’t keep up with his teammates in Red Square and sat alone “pouting and sulking.” He told the others he wanted to bail on the second day of meetings.

But that night, he was apparently feeling better. He decided the delegation would go to La Cantina, the Mexican restaurant. There was a Beatles cover band he wanted to see, he said. At La Cantina, he drank more and kept pressuring the band to let him play guitar or sing with them.

The band declined.

The two, ahem, “British” women showed up. One kissed Carey on the cheek and the general joined them at their table, where he told them about his job and the trip. Carey danced with one of the girls. “It was a fast dance,” according to a witness.

The general, two other Americans and the girls closed down the Mexican joint and hit a couple more bars. While stumbling back from the night of drinking, Carey opened up to one of his colleagues, again talking about not wanting to attend the next day’s proceedings.

But his drinking buddy convinced him he had to go, and Carey resolved to do his best. He didn’t get to bed until around 3:00, leaving him just four hours to sleep. By this point, Carey had apparently thrown back between 20 and 30 drinks since leaving his headquarters three days earlier.

Carey judging a cooking competition. U.S. Air Force photoDays 4 & 5: 25 vodka shots, cognac & 3 glasses of wine

Carey judging a cooking competition. U.S. Air Force photoDays 4 & 5: 25 vodka shots, cognac & 3 glasses of wineDespite his late-night booze-inspired resolution to set a good example, on the morning of July 17, Carey appeared to be having a hard time concentrating. He was 15 minutes late to the hotel lobby, looking exhausted, his eyes again bloodshot. As before, he slept through the car ride.

The demonstrations that morning were much like those the previous day. Carey was bored. And again he had problems with the Russian linguist, loudly correcting her translations in a crowded room, insulting her and embarrassing himself. The Russians were upset, but the translator—taking the high road—smoothed it over.

Carey then proceeded to embarrass himself further by attempting a lame joke with another translator. In a misguided attempt at levity, Carey proceeded to ask the man, “Can you hear me now?” Over and over again, invoking the then decade-old Verizon ad campaign.

The translator didn’t get it. Neither did the Russian brass Carey was there to make nice with. “The Russians were looking at him like are you crazy?” one witness said.

Then the drinking began.

At lunch that day, the number of toasts went up from the previous day’s nine to 25. According to witnesses, Carey participated in all of them. He even had a little wine on the side. During the meal, Carey’s face and eyes reddened and his speech slurred. He interrupted some of the toasts, irritating his Russian hosts.

He was wrecked.

“That’s the deal when you go to a Russian toasting event—you’re into the toasts,” Carey told an investigator. “The nice thing is that the toasting glasses are not full ounce glasses.”

But the glasses were full enough to get the general drunk, twice.

On the ride back to the hotel Carey disco-napped in the car but sprang to life once the group reached the front doors. He posted up in the hotel lounge and finished off a bottle of cognac left over from the day’s proceedings. Then he switched to wine.

Carey wanted to pull an all-nighter before flying home, in order to “get his body clock back in sync,” he said. Most of his associates fled. One delegate said he “didn’t want to end up in another situation like the night before.”

Some of the delegation stayed up with him and they chatted all night with the cigar lady about science and technology. In the morning, Carey and his delegation flew home. No further incidents were reported.

When they landed, someone complained. The investigation into Carey’s conduct started on July 30. The general declined to answer many questions and responded vaguely to others. “Carey’s account of events varied greatly at times from those of the other U.S. members on the trip,” an interviewer wrote.

But the rest of the American delegation recalled the five-day bender with total clarity. It’s clear, reading the investigators’ report, that every other person on the trip told the same story.

That Carey acted like a total frat boy.

Worse, the general apparently realized while in Moscow that the supposedly British women he cavorted with two nights in a row posed a security risk—but that didn’t stop him from drinking and flirting.

“It just seemed kind of peculiar that we saw them one night and then saw them again later while we were there and for people who are in business to be kinda conveniently in the same place where we’re at, it seemed odd to me,” Carey told an investigator.

Same thing with the cigar vendor. “She was asking questions about physics and optics and I was like, dude, this doesn’t normally happen. … A tobacco story lady talking about physics in the wee hours of the morning doesn’t make whole lot of sense.”

What also doesn’t make sense is how the man then in charge of some of the deadliest weapons in human history decided that a diplomatic mission to a rival superpower was a fine time to get shitfaced, chase sketchy women and insult the very people he was sent to impress.

August 7, 2025

Breaking Points Interviews Green Beret Gaza Whistleblower: Israel’s War Is ‘ANNIHILATION’

YouTube link here.

August 6, 2025

Scott Horton: Who Opposed Nuking Japan?

By Scott Horton, Antiwar.com, 8/5/25

“The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.” —Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower

“In 1945 Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. … The Secretary, upon giving me the news of the successful bomb test in New Mexico, and of the plan for using it, asked for my reaction, apparently expecting a vigorous assent. During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.’ The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude.” —Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower

“The use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul.” —Herbert Hoover

“[T]he Japanese were prepared to negotiate all the way from February 1945 … up to and before the time the atomic bombs were dropped; … [I]f such leads had been followed up, there would have been no occasion to drop the bombs.” —Herber Hoover

“I told [Gen. Douglas] MacArthur of my memorandum of mid-May 1945 to Truman, that peace could be had with Japan by which our major objectives would be accomplished. MacArthur said that was correct and that we would have avoided all of the losses, the Atomic bomb, and the entry of Russia into Manchuria.” —Herbert Hoover

“MacArthur’s views about the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were starkly different from what the general public supposed. When I asked General MacArthur about the decision to drop the bomb, I was surprised to learn he had not even been consulted. What, I asked, would his advice have been? He replied that he saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb. The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.” —Norman Cousins

“General MacArthur definitely is appalled and depressed by this Frankenstein monster. I had a long talk with him today, necessitated by the impending trip to Okinawa. He wants time to think the thing out, so he has postponed the trip to some future date to be decided later.” —Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s pilot, Weldon E. Rhoades

“[General Douglas] MacArthur once spoke to me very eloquently about it, pacing the floor of his apartment in the Waldorf. He thought it a tragedy that the bomb was ever exploded. MacArthur believed that the same restrictions ought to apply to atomic weapons as to conventional weapons, that the military objective should always be limited damage to noncombatants…MacArthur, you see, was a soldier. He believed in using force only against military targets, and that is why the nuclear thing turned him off…” —Richard Nixon

“The Japanese were ready for peace, and they already had approached the Russians and the Swiss. And that suggestion of giving a warning of the atomic bomb was a face-saving proposition for them, and one that they could have readily accepted. In my opinion, the Japanese war was really won before we ever used the atom bomb.” —Under Secretary of the Navy, Ralph Bird

“The Japanese position was hopeless even before the first atomic bomb fell, because the Japanese had lost control of their own air.” —General “Hap” Arnold

“The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military point of view, in the defeat of Japan.” — Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet

“The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace before the atomic age was announced to the world with the destruction of Hiroshima and before the Russian entry into the war.” Adm. Nimitz

“The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons … The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.” —Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Truman

“Truman told me it was agreed they would use it, after military men’s statements that it would save many, many American lives, by shortening the war, only to hit military objectives. Of course, then they went ahead and killed as many women and children as they could, which was just what they wanted all the time.” —Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Truman

“The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb. … The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.” — Major General Curtis LeMay, XXI Bomber Command

“[LeMay said] if we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals. And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?” —Robert MacNamara

“The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment … It was a mistake to ever drop it … [the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it.” — Fleet Admiral William Halsey Jr.

“I concluded that even without the atomic bomb, Japan was likely to surrender in a matter of months. My own view was that Japan would capitulate by November 1945. Even without the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it seemed highly unlikely, given what we found to have been the mood of the Japanese government, that a U.S. invasion of the islands scheduled for 1 November 1945 would have been necessary.” —Paul Nitze, director and then Vice Chairman of the Strategic Bombing Survey

“[E]ven without the atomic bombing attacks, air supremacy over Japan could have exerted sufficient pressure to bring about unconditional surrender and obviate the need for invasion. Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey’s opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.” —U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, 1946

“Just when the Japanese were ready to capitulate, we went ahead and introduced to the world the most devastating weapon it had ever seen and, in effect, gave the go-ahead to Russia to swarm over Eastern Asia. Washington decided it was time to use the A-bomb. I submit that it was the wrong decision. It was wrong on strategic grounds. And it was wrong on humanitarian grounds.” —Ellis Zacharias Deputy Director of the Office of Naval Intelligence

“When we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew that we knew we didn’t need to do it, we used them as an experiment for two atomic bombs. Many other high-level military officers concurred.” —Brigadier General Carter Clarke, the Military Intelligence officer in charge of preparing summaries of intercepted Japanese cables for President Truman and his advisors

“The commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, Ernest J. King, stated that the naval blockade and prior bombing of Japan in March of 1945, had rendered the Japanese helpless and that the use of the atomic bomb was both unnecessary and immoral. —Brigadier General Carter Clarke

“I proposed to Secretary Forrestal that the weapon should be demonstrated before it was used… the war was very nearly over. The Japanese were nearly ready to capitulate… My proposal… was that the weapon should be demonstrated over… a large forest of cryptomeria trees not far from Tokyo… Would lay the trees out in windrows from the center of the explosion in all directions as though they were matchsticks, and, of course, set them afire in the center. It seemed to me that a demonstration of this sort would prove to the Japanese that we could destroy any of their cities at will… Secretary Forrestal agreed wholeheartedly with the recommendation… It seemed to me that such a weapon was not necessary to bring the war to a successful conclusion, that once used it would find its way into the armaments of the world.” —Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Navy Lewis Strauss

“In the light of available evidence I myself and others felt that if such a categorical statement about the retention of the dynasty had been issued in May 1945, the surrender-minded elements in the Japanese government might well have been afforded by such a statement a valid reason and the necessary strength to come to an early clear cut decision. If surrender could have been brought about in May 1945, or even in June, or July, before the entrance of Soviet Russia into the Pacific war and the use of the atomic bomb, the world would have been the gainer.” —Under Secretary of State Joseph Grew

And for what it’s worth, then-Army Chief George Marshall wanted only to hit military facilities with it, not cities.

Scott Horton is editorial director of Antiwar.com, director of the Libertarian Institute, host of Antiwar Radio on Pacifica, 90.7 FM KPFK in Los Angeles, California and podcasts the Scott Horton Show from ScottHorton.org. He’s the author of the 2017 book, Fool’s Errand: Time to End the War in Afghanistan and editor of The Great Ron Paul: The Scott Horton Show Interviews 2004–2019. He’s conducted more than 5,000 interviews since 2003. Scott lives in Austin, Texas with his wife, investigative reporter Larisa Alexandrovna Horton. He is a fan of, but no relation to the lawyer from Harper’s. Scott’s Twitter, YouTube, Patreon.

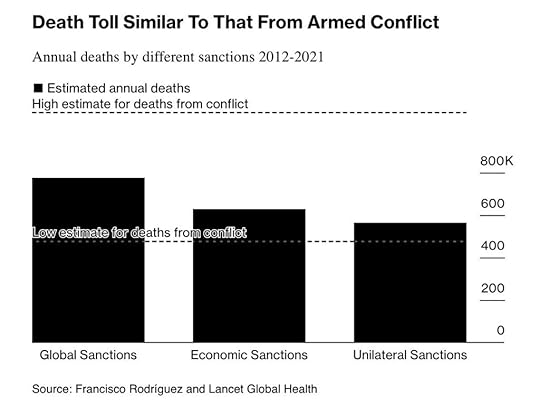

Death Toll from Sanctions Similar to That of Armed Conflict

Chart courtesy of The Daily Lever, July 24, 2025

Sanctions can be just as deadly as armed conflict. (Source: The Lancet)

August 5, 2025

Trump threatens BRICS with tariffs over ‘anti-US’ agenda

RT, 7/31/25

US President Donald Trump has said he is considering tariffs on BRICS nations, accusing the group of adopting anti-US policies. Earlier, Trump warned that any attempt by the group to challenge the US dollar would be met with harsh economic measures. BRICS members targeted by his latest sanctions, such as India and Brazil, said they would protect their domestic interests.

Speaking at the White House on Wednesday, he claimed the group is working to weaken the dollar and strip it of its role as the world’s reserve currency.

“They have BRICS, which is basically a group of countries which are anti the United States, and India is a member of that if you can believe it,” Trump said. “It’s an attack on the dollar, and we’re not going to let anybody attack the dollar.”

The same day, Trump announced that India will face 25% tariffs and additional penalties starting on Friday over its continued trade with Russia. He said the tariffs were imposed partly because of India’s membership in BRICS, and partly because of what he called a “tremendous” trade deficit with New Delhi.

Trump also imposed a 50% tariff on all goods from Brazil effective August 1, claiming the country poses a threat to “the national security, foreign policy, and economy” of the US.

BRICS was established in 2006 by Brazil, Russia, India, and China, with South Africa joining in 2010. Over the past year, it has extended membership to Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia. BRICS partner countries include Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Uganda, and Uzbekistan.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has said BRICS countries are seeking alternatives to the dollar to shield themselves from Washington’s “arbitrariness,” calling the shift irreversible.

Last year, Russia’s Finance Ministry said national currencies made up 65% of BRICS trade, with the dollar and euro falling below 30%. Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov said BRICS is not a rival to the US, but warned that “the language of threats and manipulation… is not the way to speak to members of this group.”

The Continuing Tragedy of Ukraine: An Interview with Nicolai Petro

The following is an interview with Nicolai N. Petro about his book, The Tragedy of Ukraine (De Gruyter, 2023). It was conducted by István Szabó of the Hungarian daily newspaper Magyar Nemzez on July 12, 2025.

What inspired you to approach the Russia–Ukraine conflict through the lens of classical Greek tragedy? Why did you choose this particular cultural reference?

I had been thinking about writing a book about Ukraine ever since our first visit there in 2008. When I won a Fulbright Grant to spend the 2013-2014 academic year in Odessa, I thought of writing about the influence of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukrainian society. This topic, however, was quickly overtaken by the events that were unfolding around us—the Maidan uprising.

I subsequently spent several more years thinking about how such a seemingly stable society could shatter in just a few short months. I found no suitable approach, until I stumbled upon Professor Richard Ned Lebow’s book The Tragic Vision of Politics.

In it, he looks at modern conflicts through the lens of political realism inspired by Thucydides’ classic history of the Peloponnesian War (431 to 404 BC). Thucydides traced the roots of this conflict among the Greeks to the collapse of the traditions and practices that had sustained their civilization for so long. Simply put, war erupted because the leaders of Athens and Sparta decided that they no longer shared ideas, identity, and values, and so were no longer bound to each other.

I felt that this was a good description of what had taken place in relations between Russians and Ukrainians since the Orange Revolution of 2004.

In your book, the concept of catharsis plays a central role. How do you interpret catharsis in the context of the current geopolitical situation, particularly with regard to Ukraine?

Recurring conflict is a problem of the heart, as much as it is of political institutions. This is as true of nations as it is of individuals. The enduring value of classical Greek tragedy is that it seeks to induce a change of heart—which the Greeks called catharsis—a purging of emotions so powerful that it allowed emotions such as pity and compassion to enter the soul, and to take the place of rage.

By showing the horrors that result from the unyielding pursuit of vengeance, Greek playwrights tried to lead citizens away from anger and vengeance, and toward compassion. By replacing rage with reason, they believed catharsis could liberate both individuals and societies from the tragic cycle of vengeance.

Catharsis is based on the ability to see the enemy, the Other, as a co-sufferer, so that endless conflict can give way to dialogue, and eventually forgiveness. Put another way, no conflict can ever be resolved without a catharsis.

What could such a form of catharsis mean for the future of the Ukrainian state and society? Is it even possible in the midst of an ongoing war?

I believe that Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus would prescribe for Ukrainian society what they prescribed for themselves– a profound shift in social attitudes that would allow people who hate each other to engage in dialogue. Without such a catharsis there can be no dialogue about the future, because there is no shared future.

In my book I suggest that Ukraine would benefit from a Truth and Reconciliation process, which has helped scores of countries to heal conflicts, both domestic and international. This would be an important step in reconciling the antagonistic segments of Ukrainian society, and in restoring trust in government institutions.

In your book, you highlight that many people in eastern and southern Ukraine identify with Russian cultural identity. What are the consequences if this identity is not recognized at the political level?

The persistent divisions within Ukrainian society derive from its history of being a focus of contention between rival empires, including Russia, Austro-Hungary, and the Ottomans. When these empires collapsed in the early 20th century, their frictions were often inherited by the countries that emerged from them.

The largest community within modern Ukraine are those seeking to preserve a cultural, religious, and linguistic tie with Russia. In my book I refer to them not as “Russian speakers,” which oversimplifies their identity, but as Maloross Ukrainians. This older term was commonly used before the Bolshevik Revolution because it highlights that this identity goes far beyond language and religious affiliation, even though these are the most widely discussed points of contention today.

These two Ukrainian identities, which can be thought of as two nations living in one state, have not yet learned how to live together, and this has led to the bloody war that the country is enduring today.

Do you think it is possible for Ukraine to develop an inclusive national narrative in the long term—one that provides a legitimate place for its Russian-speaking population? If so, how?

It is certainly possible. Other countries have done it—Belgium, Switzerland, Canada, India, Indonesia, to name a few. The main obstacle that needs to be overcome is atavistic nationalism, which says that a nation must consist of only one monolithic identity, and which therefore sees all other identities as threats. Such nationalism seeks to redefine and restrict ethnicity, language, religion, and historical memory. Eventually, however, the list expands to include almost any characteristic, which is why nationalism is often seen as a precursor to Fascism and Nazism.

What role has the international community—especially the West—played in either reinforcing or exacerbating Ukraine’s internal tensions?

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio recently stated (Fox News, 5 March 2025) that the West is involved in a proxy war against Russia in Ukraine. This makes it a continuation of what 19th century British rulers commonly referred to as “The Great Game”—a global chess match between rival powers aimed at shifting the overall balance of power in their favor.

The impact on any nation caught up in the “game” has always been devastating, as the competing powers each promote their indigenous supporters. This inflames existing social tensions, and turns every political debate into a choice of good versus evil. That is why Ukrainian nationalists referred to their Maidan coup d’etat against president Viktor Yanukovych, as a “civilizational choice” in favor of the West. This in turn led to the rebellions of Crimea and Donbass, which were supported by Russia.

In your view, would the West ever be willing to accept a Ukrainian national vision that is not exclusively Western-oriented but also culturally multipolar? Are there any historical or international precedents for this?

The West contains many diverse elites, with many diverse agendas. While it is hard to imagine the current political leadership of the EU accepting a neutral Ukraine that had good relations with both Russia and the EU (this was already an obstacle during the EU Association talks in 2013), the political climate in Europe and the United States seems to be shifting away from this group, and toward elites that place their own national interest first. This is causing the once monolithic West to fracture.

It is therefore possible that, when current political leaders are replaced by their national electorates, their successors will seek better relations with Russia, even at the expense of Ukraine, since Russia is a far more important neighbor for Europe.

What do you see as the biggest challenge in conveying your book’s message to the direct actors in the conflict? How might this kind of discourse gain wider societal resonance?

The biggest challenge in the resolution of any conflict, large or small, is getting the parties now immersed in the conflict to recognize the extent to which they themselves helped to bring about this conflict. That is why the Greeks said that true object of dialogue was self-transformation. Classical Greek tragedy is, quintessentially, a series of dialogues in which we are all encouraged to reflect on our own tragic flaws. Only when the participants can grasp how their own actions have stoked the hatred of others, can they choose a different path.

Welsh social critic Raymond Williams captured this perfectly when he said that, “Tragedy rests not in the individual destiny. . . but in the general condition, of a people reducing or destroying itself because it is not conscious of its true condition” (Modern Tragedy, p. 196).

Greek playwrights could convey this message through plays that were mandatory for the entire polis. Today we cannot gather all citizens in one place, but governments could use social media to spread a message of tolerance, dialogue, and forgiveness of our enemies, if they wanted to.

Of course, in a world of rival nation-states it would be naïve to expect political leaders to do so, unless it could be shown to benefit their own political careers, and as being the supreme national interest. Over the past few decades several senior diplomats have tried to steer American foreign policy in this direction, including such luminaries as George F. Kennan, Amb. Jack F. Matlock, Jr., and Amb. Chas W. Freeman, Jr..

On a personal level, how has your perspective on the Ukraine–Russia relationship changed during the course of your research? Was there any insight that particularly surprised you?

I was struck by the consensus that once existed among scholars regarding the totalitarian aspirations of nationalism. Reinhold Niebuhr once commented that nationalism is when “the nation pretends to be God.” The danger of this seems to have been almost entirely forgotten today.

I was impressed by the successes of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in healing social wounds that have festered for many decades. In my book I look at what they were able to accomplish in South Africa, to prevent violence after the end of the apartheid regime; in Guatemala, to support reconciliation after nearly four decades of civil war and American intervention; and in Spain, to assist the peaceful transition to federalism and democracy after 36 years of dictatorship.

In a similar vein, inside Ukraine we can point to the remarkable peacemaking efforts of Sergei Sivokho, a close friend of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky who, with the president’s support, set up a National Platform for Reconciliation and Unity. Unfortunately, he was hounded out of his position by Ukrainian nationalists, and died soon afterwards.

On a personal note, I find it amusing that I am sometimes accused of being too naïve about politics. I would counter that if a policy fails to achieve the results it promises (like sanctions on Russia, which were supposed to lead to the rapid collapse of the Russian economy), then expecting success from more of the same is both naïve and irresponsible.

Policies should be judged by their results, and when a policy has persistently failed, governments should consider other approaches. In the case of Ukraine, Western efforts to promote security through escalation have patently failed. Why not, then, see if better results can be achieved by reducing military involvement, rather than expanding it?

There is historical precedent for this—the 1953 Korean Armistice Agreement. After a series of contentious negotiations, a ceasefire was finally achieved not through increasing arms and support for South Korea, but through a total embargo on any new weapons being introduced onto the peninsula. This embargo was monitored by the United Nations. The parties also agreed to hold later talks on a permanent peace treaty, but by 1954 the United States had already moved on to the conflict in Vietnam. As a result, the ceasefire that was meant to be temporary became permanent. While this is certainly not an optimal solution, it has resulted in more than seventy years of peace.

Another criticism that I sometimes hear is that I minimize the role of Russian aggression. Again, I disagree. I have always pointed out that the invasion of Ukraine is a violation of international law, but my study of Ukrainian history leads me to conclude that, while Russia initiated the current level of hostilities, their roots go much, much deeper. Understanding this complex history does not in any way minimize, mitigate, or justify Russia’s attack on Ukraine. It is however, vital for the healing of Ukrainian society, and for achieving a lasting peace after the war.

About Nicolai Petro:

Nicolai N. Petro is Professor of Political Science at the University of Rhode Island, where he previously held the Silvia-Chandley Professorship of Peace Studies and Nonviolence. His scholarly awards include two Fulbright awards (one to Russia and one to Ukraine), a Council on Foreign Relations Fellowship, and research awards from the Foreign Policy Research Institute, the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies in Washington, D.C., and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. In 2021 he was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies at the University of Bologna, Italy.

August 4, 2025

Brian McDonald: Too rich for BRICS, too Russian for Brussels

By Brian McDonald, Substack, 7/23/25

There are questions that sound academic until you realise entire wars have been built on their answers. One of them, heavy with history and the kind of political quicksand that swallows men faster than bullets, is this: Where does Russia belong?

Not in the atlas—that part’s clear. Russia’s right where it’s always been, draped across the continents like a great old beast, spine deep in Siberia, face still turned—half-defiantly—toward Europe. But if you look past the borders and into the bones, the question comes again: what is it now?

Is it still the outlier in the European family—wounded, estranged, but recognisably kin? Or has it thrown in its lot with the Global South, shoulder to shoulder with Brazil and South Africa in that loose alphabet of ambition we call BRICS?

The numbers say one thing. The stories we tell say another. And somewhere between the two lies the truth—stubborn, shifting, and hard to hold.

Take the latest data measured by the IMF. Russia’s PPP-adjusted average (net) salary now sits at $3,340 a month—a not-so-gentle reminder that this is no longer an “emerging market” in any serious sense. That puts it above Italy ($3,307), Czechia ($3,022), and Lithuania ($2,870). It’s knocking at the door of Spain ($3,459) and not far off the UK ($3,597). And the direction of travel matters: incomes in ruble terms rose 16% year-on-year, according to Rosstat. The numbers aren’t just big—they’re getting bigger.

Then we look at BRICS. China stands at around $2,000, a full tier above Brazil ($1,210), India ($900), or South Africa ($965). For all of China’s rise—its bullet trains, high-rises, and sprawling megacities—Russian living standards remain, on average, markedly higher. It doesn’t really swim in the same waters as its BRICS partners. The shelves are fuller, the flats warmer and better air conditioned, the middle class—however bruised—more securely anchored. This isn’t the landscape of unfinished industrial revolutions or sprawling poverty. And yet, BRICS was never really about income. It was about leverage. A counterweight. A refusal to accept the world as arranged in Brussels or Washington. And here, Russia fits like a clenched fist: sanctioned, ringed by rivals, yet impossible to ignore. A battle-scarred heavyweight among rising strivers.

But averages are for economists and liars. Russia remains a country of gulfs, not gradients. The gap between richest and poorest regions has now hit a record ₽182,000 per month—a difference of $2,330. In Chukotka, the average salary’s $2,855. In Ingushetia, it’s $525. In Moscow, Yamalo-Nenets, Magadan—you can clear $1,850. In Chechnya, Dagestan, Ossetia—you’ll be lucky to get past $600.

And those are just the visible figures. The informal economy is vast, anywhere from 30 to 50 percent of GDP by some estimates. Wages are paid in cash, favours, or silence. The real economy—the one people actually live in—moves in ways no spreadsheet can mode

But even through the distortion, a picture emerges. This isn’t India or Brazil. It isn’t South Africa. Not in income, not in infrastructure, not in human capital. Russia is something else—wealthier than it lets on, more developed than many would like to admit, and far harder to categorise than any acronym can allow.

Still, the Kremlin has made its choice. Not just in trade, but in tone.

“European markets, European economies—these are dying economies,” said Maxim Oreshkin, Putin’s top economic aide, standing at a forum outside Moscow, this week, like a man delivering last rites. “Germany has been in stagnation for years.” In his eyes, only India compares to Russia in long-term potential—but even there, he says, “the mentality” stifles initiative.

You may scoff. You might nod along. But you can’t ignore it—this is how the Kremlin sees the world in 2025. And from that vision comes policy. Comes alignment. Comes strategy.

It’s not just rhetoric, either. Russia is rebuilding itself in the image of South Korea’s chaebols—not through design, perhaps, but necessity. The old oligarch model is being nudged aside. In its place: corporate giants like Severstal, Norilsk Nickel, Rosatom, sprawling, vertically integrated, politically aligned.

Billionaire Alexei Mordashov has warned this shift comes with risks—monopolies, stagnation, a strangling of small business. But is it worse than what came before? The era when Roman Abramovich, Mikhail Friedman, Andrey Melnichenko stripped billions out of the country, bought mansions in London, chalets in Switzerland, parked their yachts in the Med, and passed through airports with more passports than principles?

One Moscow tycoon told me last year, without blinking, that over $2 trillion net was “ripped out of Russia” between 1991 and 2021. A staggering sum. A slow bleed, year by year. Maybe now, at last, the arteries are being tied off.

So again we ask—where does Russia belong?

Not in BRICS, if we’re talking economic fundamentals. Its income levels, industrial base, and urban development look more like Warsaw or Milan than Pretoria or São Paulo. It may trade with the Global South, but it doesn’t live like it.

And yet… it doesn’t quite belong in Europe either. Not politically. Not anymore.

It’s been a long while in the cold now. Years of it. Locked out, boxed in, talked about in every room but never let through the door. NATO’s right up at the fence, sufficiently close to hear it breathe. And all the while, Western Europe pulls its collar up and crosses the street. Brussels has been doing its best impression of a fainting duchess, pretending this is all one-way traffic—as if history were a thing that only happens to other people. And every Russian artist, every athlete, every voice with that distinctive accent—brushed with the same shade of guilt.

Some of it, of course, is Russia’s own making. No getting around that. But by no means is all of it. And the effect’s the same either way: a continent turning away from a country that once helped shape its soul.

Because let’s not kid ourselves—Russia is European. Not just on the map, but in the marrow. In its music, its cathedrals, its tragedies. In the long, bleak arc of its novels. It suffers like Europe. It thinks like Europe. It dreams in the same key.

What are Pushkin, Tolstoy, Chekhov, if not European masters? What is Tchaikovsky if not the echo of a continent? Have we forgotten Tarkovsky? Shostakovich and his Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk?

What of Orthodox Christianity, born of Byzantium, rooted in Constantinople, branching into the same soil as Rome and Athens?

That Western Europe has chosen to forget this—out of fear, fury, or fatigue—is a tragedy. That Russia might forget it too would be a far greater one.

So no, Russia doesn’t fit neatly into BRICS. But neither is it fully out of Europe. It’s caught between orbits, spinning under a sky that no longer knows how to name it.

Maybe that’s the most Russian place to be of all.

Can BRICS deliver beyond the rhetoric? experts weigh in

By Ricardo Martins, Intellinews, 7/22/25

Ricardo Martins is based in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and has a PhD in Sociology specialising in European politics, geopolitics and international relations.

What started off in 2009 as an eclectic coalition of emerging economies seeking greater global influence has crystallised into something far more consequential: a group that US President Donald Trump now considers threatening enough to warrant punitive tariffs. During BRICS’ recent summit in Rio de Janeiro, the irony was not lost on Brazilian President Lula da Silva, who dismissed Trump’s additional 10% tariff threats as signs of “desperation mode,” and on the South African leadership, who saw the threats as validation that “BRICS matters and is relevant.”

But beyond the headlines and diplomatic posturing lies a more complex story, here revealed through conversations with experts across five continents. Their perspectives paint a picture of a world in transition, where traditional alliances are thrown into disarray and new partnerships are being forged – sometimes reluctantly, sometimes with great enthusiasm.

Brazil’s sustainability gambit: leading by example or struggling with contradictions?

Claudya Piazera, CEO of Smart8 LCC and a Circular Economy Ambassador, who has worked with UNDP, UNCTAD, and WIPO, embodies Brazil’s ambitious vision for BRICS leadership. “Brazil stands to gain significantly from BRICS’ infrastructure finance and South-South cooperation – a pathway to more sustainable investment in agroforestry, renewable energy, and circular economy projects,” she explains, her voice carrying the enthusiasm of someone who has long navigated the corridors of international organisations.

However, Piazera’s analysis also lays bare the central paradox of Brazil’s BRICS strategy. While the country positions itself as a bridge between climate ambition and development needs, “persistent governance challenges, particularly corruption,” threaten to undermine its credibility. “Such issues not only stall progress in sustainable development and circular economy innovation but also erode Brazil’s credibility among G7 nations and key international institutions,” she observes.

Brazil’s approach reflects broader BRICS dynamics, characterised by an everlasting tension between aspiration and execution. The country sees the bloc as offering “economic opportunity through trade diversification,” “diplomatic autonomy,” and “soft power gains through collaboration in cultural, technology, and educational initiatives.” Yet internal resistance comes from “fiscal hawks and environmental advocates worried about standards and governance transparency in some partner nations.”

The Latin American ripple effect: Cuba, regional integration, and strategic autonomy

The Rio Summit’s expansion to include partnerships with Cuba, Nicaragua, and other Latin American nations signals a potential transformation of regional dynamics. Chile and Uruguay were invited to participate in the BRICS summit. Venezuela’s accession bid, however, was vetoed by Brazil during last year’s gathering in Kazan over democracy concerns following a disputed election, which saw President Nicolas Maduro secure a third term amid widespread allegations of fraud. Although Lula later signalled that this position may change. While Latin America has been considered the United States’ “backyard” for decades, the BRICS expansion now offers an alternative integration model that bypasses traditional North-South dependencies.

The Rio summit’s final declaration, featuring “the strongest pro-Palestinian language ever in a BRICS document” and condemnation of “illegal attacks on Iran,” firmly places Latin America within broader Global South solidarity networks. This represents a significant shift from the region’s historical tendency to avoid taking sides in global conflicts, driven partly by US pressure and partly by pragmatic considerations.

For countries across the region watching Brazil’s experiment, the stakes are enormous. Success could inspire broader Latin American engagement with BRICS, while failure might reinforce traditional dependencies on Washington. The establishment of the BRICS Multilateral Guarantees and progress towards alternative payment systems offer tangible benefits that extend beyond Brazil’s borders.

Global South voices: from the UAE’s pragmatism to Algeria’s aspirations

Dr. Kristian Alexander, Senior Fellow at the Rabdan Security & Defense Institute (RSDI) in Abu Dhabi, represents a voice of the UAE’s pragmatic approach to BRICS engagement. “For the UAE, participation in BRICS+ represents an opportunity to diversify its global partnerships, reduce dependency on Western-centric institutions, and engage with high-growth economies in the Global South,” he explains.

The UAE’s strategy aligns with the Gulf states’ sophisticated hedging, using BRICS membership to balance “between traditional Western partners and emerging powers.” This approach proves “particularly useful given the shifting dynamics in the Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Indo-Pacific.” Yet Alexander acknowledges challenges: “The divergent national interests among BRICS members (e.g., India-China tensions) may limit the UAE’s ability to gain consensus on regional or international issues it cares about.”

From Algeria, Karim Fess provides insight into a country that applied for BRICS membership but faced rejection. His analysis reveals both the bloc’s appeal and its limitations for aspirant nations. “BRICS represents a powerful global bloc, comprising over 42% of the world’s population and 31.5% of global GDP,” he notes, emphasising the potential for “access to financing from the BRICS New Development Bank” as an alternative to Western institutions.

However, Algeria’s experience highlights BRICS’ implicit membership criteria. The North African country faces “formidable challenges,” including “non-membership in the WTO, limited industrial productivity, and reliance on raw material exports” that “run counter to the implicit BRICS preference for diversified, trade-engaged economies.” This tension between inclusive expansion and institutional effectiveness remains unresolved.

European dilemmas: constrained choices and strategic autonomy

European perspectives reveal the constraints facing traditional Western allies as BRICS gains influence.

The UK’s Senior Analyst at Global Weekly offers a nuanced view of Britain’s position amid BRICS expansion. The country “stands to benefit from diversifying its economic partnerships, particularly with the current administration in the US contributing to general trade instability”. However, the UK faces “significant challenges if BRICS strengthens its economic autonomy, potentially marginalising traditional Western financial and trading institutions,” he adds.

Italian analyst Leonardo Di Piazza reveals the constraints many European countries face in engaging with BRICS. Italy “tried to benefit from BRICS but this hasn’t been allowed,” he notes, citing US pressure that led the right-wing government of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to opt out of the Belt and Road Initiative agreements. “Italy has destroyed relations with Russia, signed and then (after US pressure) rejected the memorandum on the Belt and Road Initiative,” illustrating how US influence limits European strategic autonomy.

From Amsterdam, a different European perspective emerges, revealing the complex calculations puzzling traditional Western allies. Dutch political analyst Wouter Timmers argues that BRICS expansion creates both existential threats and unexpected opportunities for Europe. “BRICS will definitely determine the world market in the coming times,” he observes, suggesting a stark choice ahead: “If the EU wants to trade with BRICS countries in a good, healthy way, it will also have to improve its own market. Less USA, more EU.”

Yet Timmers also warns about the Netherlands’ current political climate, describing it as “an ultra-right state where hatred of foreigners is central,” which could hinder any pivot towards BRICS engagement. His perspective reveals Europe’s fundamental dilemma: whether to double down on Atlantic dependence or risk the uncertainties of multipolarity.

The institutional challenge: rhetoric versus reality

Multiple experts point out the gap between BRICS aspirations and weak institutional performance. From India, Soumyajit Gupta provides stark numbers: while the World Bank provides “$300bn in annual lending, the NDB (also known as “BRICS Bank”) has approved fewer than 70 projects totalling around $25bn to date, revealing institutional inertia and conservative risk appetites.”

Russian expert Andrey Kortunov offers a more measured assessment, noting that “over the last ten years, the intra-BRICS trade grew on average by 10.7% annually, while the overall global trade grew by only 3% per year.” Yet he acknowledges that BRICS “cannot become a global economic integration project” due to limited internal trade and investment flows compared to other regional arrangements.

The challenge of de-dollarisation particularly reveals institutional limitations. Moroccan analyst Yassine El Bouchikhi says that “as long as the BRICS does not attack the heart of the problem, which is the international financial system via the hegemony of the dollar and its weaponisation, these efforts will not be of critical importance in tilting the balance of power.”

The China question: dominance or leadership?

Perhaps no issue proves more divisive than Beijing’s role within BRICS. Turkish journalist Celal Çetin notes that “China’s huge economy is larger than the economies of all other BRICS countries combined,” with economic output “approximately fourteen times larger than that of South Africa and five to eight times larger than the economies of India, Russia, and Brazil.”

This asymmetry creates what Iranian expert Amir Maghdoor Mashhood describes as risks that BRICS becomes “a vehicle for Chinese geopolitical and economic expansion, undermining its broader multilateral promise.” The concern extends beyond economics to governance, with multiple analysts worried about “China dependency problems” where countries become “reliant on China, reinforcing a two-tiered structure: China as the anchor, others as dependents.”

Pakistani analyst Naik Wazir offers a different take, describing BRICS as “a modern version of the Non-Aligned Movement” where “members prioritise national sovereignty and multilateral cooperation.” This view suggests BRICS’ inherent diversity prevents any single power from dominating, despite economic asymmetries.

For their turn, Indian analysts express cautious concerns about China’s economic dominance within BRICS, with geopolitical analyst Musharraf Khan noting that “China accounts for over 50% of intra-BRICS trade and is the principal lender and investor for many new applicants,” while highlighting India’s “ballooning trade deficit with China – over $85bn in FY2024.”

Strategic analyst Manu Bhat says that “rather than it being spearheaded by China, there should be some autonomy for each of the members,” reflecting broader Indian sentiment that BRICS should avoid becoming overly China-centric. This tension is further evidenced by India’s strategic balancing act, as experts note the country’s simultaneous engagement in Western-aligned forums like the Quad while remaining committed to BRICS as a platform for “territorial integrity” and resistance to any single power’s agenda-setting dominance.

Multipolarity or new bipolarity? the defining question

The fundamental question facing BRICS involves whether it contributes to genuine multipolarity or evolves into a competing pole resembling Cold War divisions. Moroccan expert El Bouchikhi frames this as requiring “necessary clarity” about BRICS’ strategic direction, particularly regarding India’s position as incoming chair.

“India, the next chairman of the BRICS, must decide on its strategic position: either to be an important vassal of the West or to build independence with the BRICS and overcome its lack of trust in China and Russia,” argues our Moroccan interviewee. Without this clarity, BRICS risks creating “a unipolar or bipolar world” rather than genuine multipolarity.

The UK’s analyst offers a more optimistic assessment, arguing that BRICS “strongly contributes to the emergence of a multipolar world order rather than evolving into a Cold War-style pole.” He believes BRICS lacks “the cohesive ideological unity required for bipolarity” and doesn’t possess the confrontational character of Cold War rivalries.

Looking forward: the decade of decision

Expert insights for BRICS’ future point to both convergence and divergence in expectations. Brazilian expert Piazera envisions BRICS evolving “into a proactive architect of a global green transition, regenerative growth, and Inclusive Finance for all,” focusing on sustainable development priorities while warning against becoming “opaque, inward-looking, or overly politically consolidated around any one power.”

From the UAE, Dr. Alexander advocates for BRICS becoming “a platform for pragmatic multilateralism, rather than an anti-Western alliance,” focusing on development finance, digital cooperation, and South-South diplomacy. He warns against BRICS becoming “an ideologically rigid bloc that mimics Cold War bipolarity.”

Russian expert Kortunov claims that BRICS can become “one of the most efficient mechanisms that the rising Global South has within its reach to make its voice heard in future discussions on the new world order,” but requires enhanced institutionalisation and focus on specific problems rather than broad declarations.

The Trump test and beyond

As Trump has explicitly threatened BRICS, the burgeoning bloc gears up to endure its first major external stress test. The expert consensus suggests that Trump’s confrontational approach and aggressive trade policies may paradoxically strengthen BRICS by validating the need for alternatives to Western-dominated institutions.

Yet success is not guaranteed. As Algerian expert Fess observes, BRICS faces “three key pitfalls: instrumentalisation by dominant powers, ambiguity in purpose, and rhetoric without results.” The next decade will show whether BRICS can overcome internal contradictions to deliver concrete outcomes that justify its members’ strategic investments.

The stakes extend far beyond any single bloc or rivalry. BRICS represents the Global South’s most ambitious attempt to reshape the international order since decolonisation. Whether it builds genuine multipolarity or fractures under internal pressures will determine if the emerging world order enhances human agency or perpetuates domination under new management.