David Hadbawnik's Blog, page 9

March 20, 2011

2011 Buffalo Small Press Book Fair

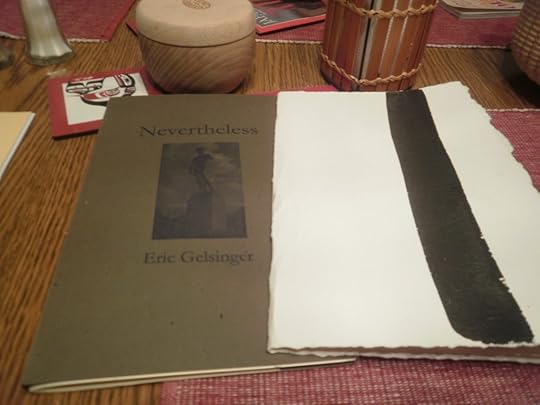

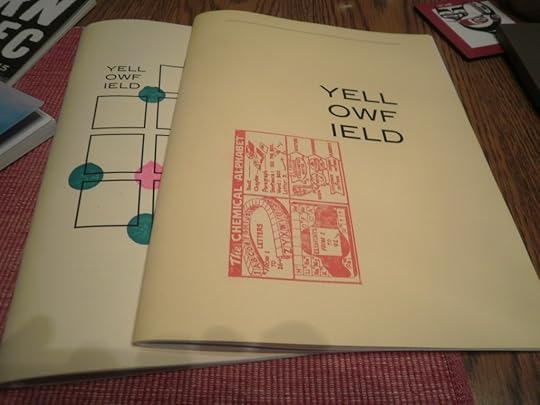

It was a briefer visit than usual to the Small Press Book Fair this year, as I did not share a table with anyone, and the workload kept me from hanging out very long. Tina got to go for the first time this year, though, and we had the chance to chat with a bunch of people and see what everyone was up to in the print world. I was especially impressed to see a former creative writing student of mine helping out at a table, and other current UB undergrads promoting their print and zine work. Here's what I came home with:

Couple of chaps by Eric Gelsinger, House Press

New local journal Yellow Field

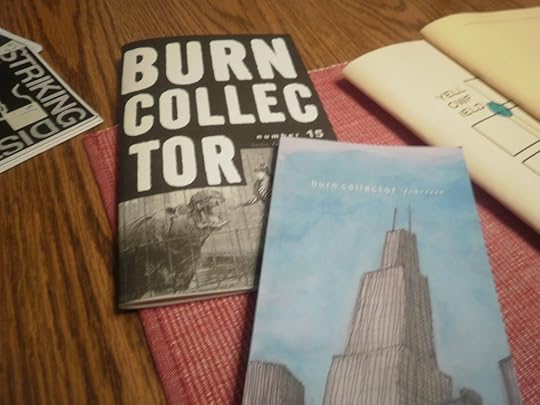

The Burn Collector zine series

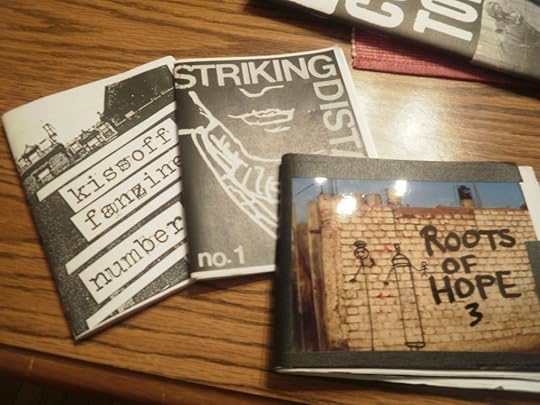

More zines, which I traded for / bought from some Toronto folks

March 4, 2011

A Tale of Two Smiths — Elliott, Sonny

Elliott Smith died a little over seven years ago — October 21, 2003. I was on a miserable flight home from Germany when I found out.

The flight was miserable because I'd been deathly ill for the last week of my stay, lying on the floor of my friend's apartment in Leipzig with an ear infection and a fever. The infection was so nasty that I couldn't hear anything out of my left ear, and I had to pump myself full of medicine just to get on the flight.

I hadn't much listened to Elliott Smith prior to that. In fact, around the time of my trip I'd been on a major Leonard Cohen kick, which my German friend happened to share, and during the worst of my illness I stared out her windows and listened to her records and my CDs while she went out to work.

We also talked about learning to play music. She was interested in taking bass lessons, and I toyed with the idea of finally learning guitar. Something about this illness and hearing about Elliott Smith, even though I wasn't a huge fan up to that point, made it snap into place for me. Upon returning home, once I'd recovered, I bought a Takamine F-360 and began to take lessons.

And I began to listen to Elliott Smith.

*

I had already known Sonny Smith for a long time at that point. We'd met via mutual friends — experimental dancers, mostly, in the young, bohemian set in San Francisco centered around places like 848 and the old Dancers Group Studio — now, if I'm not mistaken, a Skechers shoe store. A lot of people, myself included, were doing the usual dilettantish stuff, putting on shows, flirting, having affairs, becoming involved in various issues… essentially being young and trying to figure out who we were, and what this whole art thing was about.

Sonny already seemed to have a pretty good idea. He quickly secured a weekly gig at the Rite Spot, on the corner of 17th and Folsom Sts., and that became a sort of unofficial hangout for our crowd. Countless evenings were spent there, sitting at the candle-lit tables drinking drinks and coming down from the high of whatever show we'd just been to or put on, with Sonny pounding the upright piano or playing guitar as he sang his songs.

One memory in particular stands out: The bar is full, the noise level of the various conversations has reached an ecstatic pitch where it's not so much words anymore as competing tones of desire and anguish, the thrust to have oneself heard… and weaving above and throughout it is Sonny's voice and his music, not trying to drown out the noise of the talking but melding with, playing off it…

Somehow that perfectly captures the sense that even then he was doing something both part of and separate from the usual desperate art chatter. Someone was recording that night, and I have a tape of it, still.

*

I have yet to attempt to learn one of Elliott Smith's songs, but I understand that they're tremendously difficult. Smith was a huge fan of the Beatles, and the sweet melodies and complex harmonic arrangements of his music constitute almost its sole value, for me, all these years later. At his best he is a garage-version Paul McCartney to Kurt Cobain's punk-version John Lennon (though, given Smith's incredibly deft guitar parts, perhaps the better comparison is George Harrison…).

But to put it bluntly, Smith has almost no content to his lyrics aside from the anguished cry of the junkie. "Leave me alone, I'm all right" is the constant refrain, and almost the only message he manages to get across. To his credit, he faces the contradictions of his addiction head-on, for the most part, and his ability to turn a phrase and raise junk talk to the level of poetry is probably the absolute limit of what can be done with such narrow subject matter.

Take a song like "Needle in the Hay" — not even the best example, but the first that comes to mind:

Your hand on his arm

Haystack charm around your neck

Strung out and thin

Calling some friend, trying to cash some check

He's acting dumb

That's what you've come to expect

Needle in the hay

Needle in the hay

Needle in the hay

Needle in the hay

He's wearing your clothes

head down to toes, a reaction to you

You say you know what he did

But you idiot kid, you don't have a clue

Sometimes they just get caught in the eye, you're pulling him through

Needle in the hay…

The deceptively simple diction and rhyming — Smith draws out "come" to rhyme with "dumb" and then lets "expect" return to "neck" and "check" — mingles with his remarkable punning on the "needle" motif to push the whole metaphor into a poignant and painful place. A needle is never just a way to deliver junk for Smith; not only do we get the prodigal-son sense of loss ("needle in the hay") but, obviously, the "eye of the needle," which brings in not just the idea of sewing but the Biblical reference as well.

This is a trademark of Smith's. It's ultimately unsatisfying, though, to anyone not a junkie, anyone looking for him to take this gift for insight and wordplay into an area that says something about the larger human condition.

*

A recent NY Times story about Sonny Smith and his band, Sonny and the Sunsets, came to my attention the way so many things do these days, via Facebook. Having moved away from San Francisco five years ago, I've been following the ongoing saga of his musical adventures from afar, in Texas, and now in Buffalo. When I saw him play with the Sunsets at a club in SF during a visit several years ago, I felt a huge sense of relief that he'd broken through what seemed to me a long, lonely struggle with his music, and tapped into a place that felt joyfully childlike and fun, as if music and art had become once again a way of exploring youthful fields of imagination.

There was always that sense with Sonny's music, which is part of what attracted us to it all along — one of his early songs, "Let Me Be Your Baseball Player," hilariously re-imagines the typical lover's plaint in terms of the American pastime. But I also knew that he'd gone through dark periods of frustration at the grind of being a serious musician who had reached a certain level of notoriety and respect around the Bay Area (with occasional, increasing forays into New York, and up the West Coast) but little attention elsewhere, and none from the "industry."

Smith could have done many things. He could have quit. He could have gotten a "regular" job instead of the seasonal, itinerant, side jobs he so often did, which allowed him to take off on tours and studio work. He could have, not exactly "sold out," but attempted to make his music more marketable from a mainstream perspective, so that he could be picked up and promoted by a larger indie label. Many of his peers did one of these things.

Instead, with his band Sonny and the Sunsets, he seemed to settle in to a more collaborative, free-wheeling space. He'd always been collaborative and genre-bending, with a fascination for theater, film, and visual art alongside his musical focus, but now he took that to another level, with projects like "100 Records," the brilliant conceptual series of his that began to draw the attention of the art as well as the music world.

*

This is where the stories dovetail, for me, to the extent that they do at all; in every other sense, Elliott and Sonny Smith have nothing whatsoever in common as musicians or human beings (aside from, obviously, that last name). Elliott Smith often lamented the loss of his early days as an obscure musician with his band Heatmiser. As he progressed from one album to the next, increasingly solo, his junk-talk lyrics hemmed in his music thematically, to the point where there was little for him to sing about beyond the endless cycling through the disappointments and relapses of that life.

I can't help but wonder what might have happened if he'd managed to form another band and just played music again, and shifted himself into a whole new field of material to explore.

Not to make a hero out of Sonny, but to me, this was the particular triumph of the Sunsets and the recent projects — simply to have endured and reached a further space of collaboration, comradery, and creativity. It's always a shock to see the name of someone you know in a headline; but somehow it wasn't that surprising, given all the activity of Sonny and the Sunsets the past few years, to find them characterized as "one of the hottest indie bands in the country."

*

As a final note, just the video, below, for the song "Death Cream," which perfectly captures the relationship of the music to visual art and the role of imagination in the lyrics. It's a dark topic, but inflected with sci-fi weirdness and humor that widens the scope of the song. Elliott Smith simply had no way to conceptualize death other than through the lens of junk. Sonny Smith's song, by contrast, seems somehow both more innocent and (perhaps for that reason) more haunting.

February 25, 2011

More on Labor, Sports, and Wealth Distribution

The NFL owners and players are sitting down with a mediator to try to work out a labor agreement (the current one expires March 3). Today the first vague report of "some progress" has trickled out about the negotiations, which have otherwise provided a strange and silent backdrop to the labor unrest taking shape in states across the U.S. Millionaires and billionaires locked in a room in New York haggling over how to divvy up a 10-billion-dollar pie, while teachers and workers in Wisconsin fight for the right merely to do what they're doing — sit down and negotiate.

See the irony there?

I predict the following: The mediator will arrive at a compromise that involves an 18-game regular season, which nobody but the owners wants — players have legitimate concerns about the injury toll such a season would take; most fans sympathize with that, and they don't want to have to pay the bump for season tickets, and additionally simply believe it's too long.* But the owners want it, it will grow the size of the pie, and in the end that's all that matters.

*I also think fans don't like the idea of the hash this would make of single-season records. There's a rightness to 16 games that puts certain milestones in the proper degree of difficulty: 2,000 yards rushing, 50 touchdown passes, etc. Eighteen games obliterates all that.

Nevertheless, I believe the owners will still want more concessions. They will not simply get up from the bargaining table, accept the mediator's decision, and shake hands and light cigars. It will then come down to whether the hard-core of owners who want to crush the union completely win out over those who are satisfied with, say, 47% of the 10 billion rather than 48%. And so there will be a lockout.

Meanwhile, the above graph is from a series of illustrations in Mother Jones that shows the incredible disparity in wealth that has burgeoned ever wider over the past couple generations. It perfectly captures Slavoj Žižek's summary of Benedict Anderson's idea about "imagined communities." As he explains in a footnote to the first chapter of Enjoy Your Symptom!:

When, with the advent of capitalism, the symbolically structured "community" was replaced by the "crowd," community became in a radical sense imagined: our "sense of belonging" does not refer anymore to a community we experience as "actual," but becomes a performative effect brought about by the "abstract" media … Let us recall Stuart Hall's analysis of Thatcherism's political appeal: the Thatcherite* interpellation succeeded insofar as the individual recognized himself/herself not as a member of some actual community but as a member of the imagined community of those who may be "lucky in the next round" by way of their individual entrepreneurship. The hope of success, the recognition of oneself as the one who may succeed, overshadows the actual success and already functions as a success, the same as in a TV quiz show where, in a sense, "taking part in it" already is to win: what really matters is not the actual gains but being identified as part of the community of those who may win.

*Margaret Thatcher, P.M. of the U.K. from 1979-1990. From her Wikipedia entry: "Her political philosophy and economic policies emphasized deregulation, particularly of the financial sector, flexible labour markets, and the sale or closure of state-owned companies and withdrawal of subsidies to others." It's no accident that Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker has compared himself to not only Reagan, but Thatcher; and that an under-reported but important part of his budget is the ability to sell state-owned property in a no-bid process.

In short, what the chart illustrates in a slightly different way is exactly what Žižek says: most people imagine the wealth distribution in the U.S. to be a great deal more equitable than it is. One need only add that most people imagine themselves to be on the way to moving up to the next income bracket; or indeed, through some kind of extraordinary cognitive dissonance, to already be there, and it's suddenly understandable how people can identify and sympathize with millionaires and billionaires, rather than the teachers and workers who belong to their actual class.

And made no mistake: it's class warfare, all over the globe. People fighting for democracy in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, are fighting for a larger slice of the pie, a more equal distribution of wealth and resources. The illusion that's worked for so long has started to crack. Saudi Arabia is very nervous; the king has bumped social services and welfare in an attempt to maintain the imagined community there.

In every instance, it's going to take a critical mass of people disillusioning themselves in order for anything to really change.

February 18, 2011

In Defense of the Union

A most remarkable assault on unions is taking shape across the land. Not only are public service unions responsible for breaking the state budget, according to Wisconsin Governor (and Tea Party favorite) Scott Walker, but St. Louis Cardinals manager Tony La Russa is now blaming the players' union for potentially forcing star slugger Albert Pujols out of St. Louis when his current contract expires at the end of next season.

Who knew unions had so much power?

The situation with state workers, of course, is far more serious. I could care less if a superstar ballplayer eventually signs for $130 million over 7 years, or $200 million over 10. But the rhetoric is curious, and instructive to look at. And in that sense, even though the average major league baseball player is as comparable to the typical state employee as a mountain lion to a bowling pin, it actually drives at the exact same point.

La Russa claims that the union is working feverishly behind the scenes to pressure Pujols to take as much money as he can, regardless of any loyalty he might feel towards the Cards. It's not just in the manner of "twisting his arm," La Russa claims, but "dropping an anvil on [Pujols'] back through the roof of [his] house."

Why? Well, as perhaps the premier slugger of the decade, it's important (La Russa theorizes that the union believes) for Pujols to push upwards the maximum dollar amount that can be had on the open market. A rising tide lifts all boats, is the thinking here.

The same basic theory was floated when superstar pitcher Cliff Lee tested the market at the end of last season. He would wind up with the Yankees, word on the street had it, because the Yankees would offer the most money and the union would pressure him to take it, in order to set the bar for free agent pitchers down the line. In the event, of course, Lee surprised everyone by taking less money than either his current team, the Texas Rangers, were offering, OR what the Yankees were throwing at him, to go back and sign with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Lee was praised at the time for bucking the money and the union, though the union denied it had pressured him in any way, just as it has denied involvement in whatever's going on with Pujols. The irony here is that, compared with the player most similar to him, Alex Rodriguez of the Yankees, Pujols is pretty substantially underpaid:

Pujols and Rodriguez since 2001:

Rodriguez

Pujols

HR

424

408

RBI

1,236

1,230

Salary

$252M

$96.7M

Salary per HR

$594K

$237K

Salary per RBI

$204K

$79K

(Above table borrowed from espn.com)

It's easy to blame unions. There is a whiff of communism about them, and more importantly, they represent a nameless, faceless multitude that no one, in the abstract, feels a damn bit sorry for. Again, consider La Russa's rant; he doesn't demonize the team owners, for not paying Pujols what he is clearly worth on the open market. Nor does he blame the player himself, who is little short of a saint in St. Louis. And he doesn't even mention the evil sports agent.*

*I don't know who Pujols' agent is, but it was super-agent Scott Boras, of course, who hornswaggled the Texas Rangers into the ludicrous A-Rod contract way back when.

So unions are a safe target for ire and blame, and it's always a matter of putting a face to the entity before anyone thinks twice about demonizing them. This brings us to Wisconsin, where such an effort is underway — thousands have descended on the state capitol. Both sides — the workers and State Rep. Paul Ryan, who opposes them — have invoked the language of the revolutions sweeping the Middle East, Ryan memorably claiming that "Cairo has come to Wisconsin."

In a sense, he's right.

Mass demonstrations are a form of democracy. Collective bargaining is democracy. The right to gather in a group and bargain for the betterment of all is essentially what democracy is.

Funny how this doesn't bother us when the collective is bargaining not for better wages, but better prices… Well, it sort of bothers some of us when that bargaining takes the form of insurance. But this is essentially how car insurance works, and it's how health insurance works — when it works, although the industry has done its best to rig the game.

But there is a new, web-driven consumer movement that promises to exponentially raise the potential of such collective price bargaining. Last week's Time magazine featured a story on Groupon, which, as the article makes clear, is little more than a digitized, highly focused version of the traditional coupon booklet.

Groupon, the category leader, offers its subscribers—who number more than 50 million and are growing at a clip of 3 million a month—discounts on goods and services, but only if a critical mass of people agree to buy the deals that are e-mailed to them each day. The discount could be up to 90% off on a car wash, a restaurant meal, a cooking class, dental work or just about any product or service available in the 500 cities and 35 countries where Groupon operates.

It's win-win-win; consumers get a good deal, merchants move more product, and Groupon gets a cut. How much? Groupon has gone from zero to 50-million-plus subscribers since 2008. So rosy is the outlook that the company turned down a six billion dollar offer from Google. The implication is clear — Groupon, and its many imitators and competitors, have found a way to actually use the web to make money, rather than simply blend their business with advertising. They plan to be bigger than Google.

And because the money equation is inverted and the right palms are getting greased, we celebrate this kind of collective bargaining. It is simply another version of the American success story of innovation and ingenuity.*

*The rhapsodic praise for 30-yr-old founder Andrew Mason, former music major, is especially interesting.

There are some encouraging signs in Wisconsin. As I write this, firefighters — though their union has been cynically exempted from Walker's proposed denial of collective bargaining rights — have rallied to the union cause. Yet the movement to strip collective bargaining rights — the lifeblood of unions — from public workers is already afoot in Ohio. It's underway in New Jersey.

This is a nation-wide movement. It is part of a concerted Republican strategy, a longtime right-wing fantasy that fiscal hardship and the political moment are finally allowing to blossom forth. It will come to Michigan. It will come to New York.

The extreme rhetoric of politicians in state houses has already wrung massive concessions out of public workers in California and elsewhere (including Wisconsin). In a sense, again, that's how this is supposed to work — times get tough, you don't like the deal, you sit down at the table and hammer out a new one. This is what's happening, incidentally, in the National Football League as well, where the players' union and owners group are sitting down with a mediator in the hopes of working out an agreement to replace the one currently expiring.

Yet here, too, there are owners who are reportedly hell-bent on nothing less than breaking the players' union completely. The spectacle of billionaires who essentially run a legalized monopoly denying the players who provide their very product the right to bargain over a few percentage points of a 10 billion dollar pie is… sickening. I mention sports, though, because it's a somewhat simplified, highly public and instructive way of viewing collective bargaining in every instance.

And that view is, as I say, disheartening. It's becoming increasingly clear that just as the youth of the Middle East must demand democracy with bodies and blood, the next generation of workers here will have to re-fight all of the battles their parents and grandparents fought for a fair wage and the right to bargain.

If, indeed, such things remain important enough to fight for.

January 21, 2011

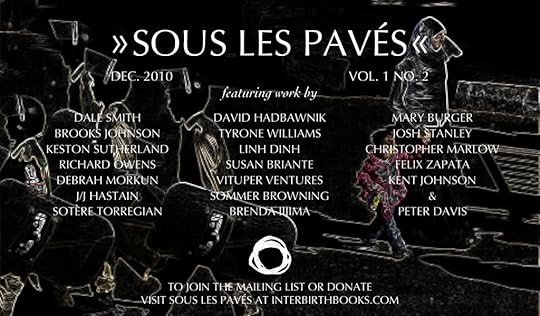

Magic, Materiality, Sous les pavés

As I began my journey to campus yesterday, walking to the stop to wait for a cross-town bus to the train station, where I'd catch the subway to the shuttle from south to north campus, I realized how seldom I'd slowed down enough lately to really pay attention to the materiality of my surroundings. Even to stand on the corner feeling the snow crunch under my boots, wandering out into the street every so often to watch for the bus, seemed a forgotten sensation, one of those timeless, in-between moments that get lost in the day-to-day hurry and grind.

When the bus came, right on schedule, I remembered odd rides on San Francisco buses that would stop and wait for seemingly no reason, making their way in fits and starts along their route according to some mysterious set of factors that no one — not even the bus driver, I supposed — was privy to. I certainly voiced my displeasure to the driver on numerous occasions when, having caught a bus and trying to get somewhere on time, it just… sat there.

This day, I pulled out the latest issue of Sous les Paves and began reading straight from the front. How refreshing to have the jigsaw puzzle of mundane transit, into which I'd been thrust by circumstances, reflected so vividly in the pages of this newsletter, cohesively and enthusiastically edited and published by Micah Robbins.*

*Full disclosure: I am a regular contributor to said newsletter, which can be ordered at Interbirth.

Before getting to that, though, I had also of necessity been looking through C.S. Lewis's large tome English Literature in the 16th Century. What struck me there, in the introduction, was Lewis's lively account of the shifting attitude towards magic as Europe emerged from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance. A nice quote: "The medieval author seems to write for a public to whom magic, like knight-errantry, is part of the furniture of romance: the Elizabethan, for a public who feel that it might be going on in the next street." This is not to be confused with witchcraft or superstition, writes Lewis; it's the "high magic" of Ficino (1433-99), Paracelsus (1493-1541), Agrippa (1486-1535), and characterized in literature, e.g., by Dr. Faustus.

A kind of magic that had "recovered" some sort of wisdom from the ancients; that, though ostensibly Christian, held a "pagan" belief in "the invisible population of the universe … those 'middle spirits … betwixt th' Angelical and Human kinde'." Lewis adds, "This mass of mysterious but not necessarily evil spirits creates the possibility of an innocent traffic with the unseen and therefore of high magic or magia." We see this "demonology" everywhere in Shakespeare — Caliban and Ariel are two such spirits. And of course, in Shakespeare as in other works of Elizabethan art, humans not only interact with spirits and magic, but partake of it; again, Prospero, Dr. Faustus, etc.

This condition of possibility, of richness, couldn't and didn't last; already, something was underway that would change it. Lewis asserts it was "the new astronomy"; "not the mere alteration in our map of space but the methodological revolution which verified it." In other words, modern science. A longer quote is necessary here:

By reducing Nature to her mathematical elements it substituted a mechanical for a genial or animistic conception of the universe. The world was emptied, first of her indwelling spirits, then of her occult sympathies and antipathies, finally of her colors, smells, tastes … Man with his new powers became rich like Midas but all that he touched had gone dead and cold. This process, slowly working, ensured during the next century the loss of the old mythical imagination: the conceit, and later the personified abstraction, takes its place. Later still, as a desperate attempt to bridge a gulf which begins to be found intolerable, we have the Nature poetry of the Romantics.

I read this as quite simply the "war of/on the imagination" that Diane di Prima has written about, a war that is not merely waged on poetry from outside but within the walls of poetry itself (if poetry can be said to have "walls") — this flattening out (of space, possibility, magic) is so much a part of our lives now that it's the very air we breathe, and as difficult to break away from. How often do we look up at birds, clouds, stars? Or down, at stones, sand, sea? Which brings me back to my bus journey and excursion into the pages of Sous Les Paves.*

*Even the title, of course, poignantly alludes to the transformation indexed by Lewis: sous les paves, la plage; "under the paving stones, the beach."

The first piece, "FACT AND REALITY," by Dale Smith, explores just such an environmental materiality, and as such is the perfect way to kick things off. Smith has always had, continues to have, a cheerfully bleak outlook* about the path of destruction that empire and capital are leading us down, and his current reading and research have taken him in this instance to Roberto Bolaño and Evan S. Connell. Of the former, he writes, "Roberto Bolaño's digressive quests … establish necessary inquiries, for he presses readers right up next to the facts of the world."

*By "cheerfully bleak" I don't mean that he's cheerful about the bleakness, only that he manages to be deeply pessimistic without ever bringing you down, or seeming like he's particularly down about any of it. A remarkable feat.

Smith brings out something in the massive 2666, Bolaño's last novel, that hadn't really occurred to me, in reading it, on a conscious level: the incessant, careful mingling in of concrete details with the otherwise "flatness" of terror this author's the master of, as if to remind us of the richness that lies beneath that surface, forgotten. Quoting a long passage in which Bolaño makes a point of mentioning the names of things, Smith writes, "the details of 'andesite rock' and 'rhyolite' and that quicksilver mirror lodge his words in a materiality … this poetic interlude in a novel of pain and suffering gives some reckoning, some relationship and perspective, to brief movements and probings over the rocky exterior of the earth."

Readers will be less familiar with Connell, who wrote a description of Custer's Little Big Horn disaster that, as Smith notes, "reads like a wicked poem, penned by the damned." (MUTILATIONS — Eyes torn out and laid on the rocks… Noses cut off… Ears cut off… etc.)

Why, Smith asks, does this "perverse insistence on fact and reality matter?" Smith has his own speculations on this; I was already thinking about Lewis, and magic, and science, and the "Midas touch" that lets us know and master everything, while experiencing nothing. Materiality "matters" because it's precisely that which escapes the "rational" mind.

*

The next page features a collage by Brooks Johnson called "REAL HEADLINE," perfectly picking up on the accent of the previous piece. It is made of, in fact, a real headline from a newspaper, along with images (perhaps from a newspaper, or some other text), which are spliced, copied, and made to overlap with each other, almost as if this "reality" (and it is, again, a brutal one) were washing up on the shore of consciousness, over and over again. There's a ship, a face, dates, type, along with various travel brochure-type effluvia, all of which resists submersion — to stick with the water image — into the blurry unreality of avoiding such materiality.

*

At this point in my journey I had reached the Delevan/Canisius metro stop, and descended into the bowels of the subway system.* I hurried down the escalator, slipping from the melting snow on my boots, and then waited with a few others on the dark platform for the next train to arrive. Consulting a timetable, I saw a flier taped there which announced, "IF YOU KNOW IT, TELL IT," over the face of a young black man, seeking information on a recent homicide. As I sat down on a bench, a kid strolled over to the edge of the platform where some women stood in a loose circle, chatting, and with a sudden gesture scattered some coins onto the tracks. I continued reading.

*That sounds like a cliche or exaggeration, but when you go down into the Buffalo subway, it really feels like you're going DOWN. First there's a looong escalator from street level, then another looong escalator down from there.

*

Keston Sutherland's piece is simply titled "10/11/10," and registers in urgent prose the recent protests in London and the police crackdown and violence that followed:

At the corner of Parliament Square the teenagers are standing on bus shelters; they are shouting for what they believe and feeling what you never will; think of the anger you waste on gifts that might be used on money; masturbation is not beloved, it's betrayal of the workers;

Here one must reflect, somewhat uncomfortably, on the reality of resistance as it intersects with the police state. During this crisis I recall that a British friend had posted — on Facebook, appropriately — a link to an interview with a British police captain who wanted to make clear that the police should not be thought of an arm of the government, i.e., not be held responsible for unpopular government actions (such as extreme cuts to education and so on). At the same time, we've been so weaned on "nonviolence" and generally not being a bother to the state that I wonder sometimes if we realize what actual resistance is. What it looks like. How it feels.

Sutherland brings it into focus, mingling first and second person, his own jumbled thoughts, your thoughts, with images and impressions from these events.

*

Riding up from the subway (on the looong escalator), I remembered the unfailingly followed etiquette throughout the Bay Area — if you're standing still, stand to the right, so that walkers can pass on the left. In Buffalo, nobody does this. Stationary riders are scattered on either side, so you have to weave between them; on a crowded escalator, everyone just has to wait. Two cops wait at street level, chatting. For a moment I wonder if they'll ask to see my ticket, but they don't.

*

Richard Owens' piece is titled "SKINNER AND COLLIS: Hasty Notes on Their Use of Neglect." This foray into the "neglected spaces" theorized in Jonathan Skinner's "ecopoetics" project is a welcome break from the harsh materiality that culminates in the first few pages of the zine with Sutherland's piece. But it's not terribly much more comforting, since the "wildness" and "wilderness" of this space is more in the manner of weeds coming up through cracks in the sidewalk, exactly the image that Skinner uses to describe those zones of the urban environment — so plentiful in Detroit and Buffalo — which capital has left behind, in many cases to be stunningly reclaimed by nature.

As Owens notes, however, these bursts of environmental relief are not some sort of return to a lost utopia: "'Corridors' and 'buffer zones' may cut through and around the space we in our species-being inhabit, but they do not … escape this space of habitation." There is no return to the Garden. Which does not mean there's no hope; Owens adds that "if we are trapped in what … is imagined here as a social totality, then not only is escape from it impossible, but the utopian itself — the way out of this mess — can only be worked toward by taking a deeper plunge into the mess…"

In other words, the answer is again to attend to these things that are so difficult to really perceive against the backdrop of capital and culture. The second half of the essay attempts to do just this, putting into conversation with Skinner's ecopoetics an essay by Stephen Collis, "Of Blackberries and the Poetic Commons." As Owens describes, Collis compares poetry itself to one of these neglected, liminal spaces in our culture, to revealing effect.

*

By now I'd reached campus, so I folded Sous les Paves up and slipped it back into my backpack, open to the page where I'd left off. Still to look at: images from Linh Dinh, surrealism from Sotere Torregian, poetry by Susan Briante, cartoons from Sommer Browning. And lots of other stuff. It was a welcome moment of breathing in, looking up, adjusting the viewfinder once more.

January 4, 2011

Out With the Old…

I've just completed a much-needed update and redesign to ring in 2011. The weeks between classes during breaks are increasingly the only time I have to accomplish tasks such as this, and it's been a busy time indeed.

Another project I'm pleased to be focusing on is a new, small-chap series for Habenicht Press, with unique covers designed by artist Carrie Kaser, who previously contributed images for two broadsides to celebrate Hoa Nguyen's visit to Buffalo last winter. Look for news on that series soon.

Tina and I will also continue the House Reading Series with a visit from Aaron Lowinger and Morani Kornberg-Weiss next Friday, Jan. 14 at 7.30pm. If you're in Buffalo, drop on by!

Since I have nothing much to say myself at the moment, I want to direct attention to a recent post by Richard Owens on Damn the Caesars.

The post responds to a piece by Keith Tuma in the most recent Chicago Review (55: 3/4). The Tuma essay critiques the avant-garde by way of the American Hybrid anthology, released last year. Here are some of the juiciest tidbits from Rich's post:

the only thing at all advance about what passes for a contemporary avant-garde is that we can anticipate being bored in advance by generally anything that identifies itself with avant-garde practice. Too many careers and too much needlessly mediocre work are too easily built on hopelessly banal pretenses to avant-gardness, innovation, experimentation and newness.

…

The fact of newness, of innovation, is always already built into efficacious work — work that productively intervenes in a situation at a specific moment in time — and so the desire to fetishize newness, avant- or advanced-ness, is to slavishly subordinate our labor to the stagflated market value of a transcendental signified that wrenches our attention away from the far more immediate, material conditions of our making.

I'll leave it with that, and urge you to visit DTC for the full text. Happy new year!

December 21, 2010

New from Habenicht Youtube

This reading took place in Spring 2010.

Here's Ben Bedard:

Part 2 can be seen here.

Here's Robin Brox:

Part 2 is here.

More on the way — enjoy!

David Hadbawnik's Blog

- David Hadbawnik's profile

- 6 followers