John Kenneth Muir's Blog, page 893

June 9, 2012

Saturday Morning Cult-TV Blogging: Ark II: "The Balloon" (December 4, 1976)

In

this episode of the Filmation Saturday morning series Ark II , the crew runs

smack into a society that, as a whole, suffers from xenophobia, a fear of outsiders or “foreigners.” Captain Jonah’s (Terry Lester) initial log

entry describes people who “refuse to

have contact with the outside world.”

But

from somewhere deep inside the isolationist village, someone is sending out

distress messages tied to floating balloons…written in Greek. After deciphering one message, the Ark II

crew comes to understand that the very people who have so calculatingly cut

themselves off from the rest of humanity are suffering from a terrible plague,

one they can’t cure on their own.

The

Ark II team finds the messenger -- an old man working a printing press near “the place of the Iron Birds,” a

destroyed air-field -- and learns that this is indeed the case. The messenger says: “We have a new enemy now…disease.”

While

Ruth returns to the Ark II via hot air balloon to work on a cure for the new disease,

Jonah attempts to convince the village’s leaders to “open” their hearts and

minds to others. Unfortunately, he and a

young boy fall prey to the disease, and only reinforce the fear of strangers. Now outsiders are disease carriers.

Meanwhile,

Ruth and Samuel must clear a path to get the Ark II inside the village, and

deliver inoculations to all the sick people.

Like

its predecessors, “The Balloon” is a message-heavy installment of this Saturday

morning series. In “The Tank,” we met

people who shunned machines because they believe machines caused war. Here, we meet characters who refuse to deal

with outsiders, because they fear attack from them. In

both cases, people have responded to a terrifying situation irrationally, by a

blanket rule about the things they perceive caused them harm.

In real life, of course, America has witnessed periods of intense xenophobia over the last two centuries, not the least of

which has been in the decade following the 9/11 terror attacks. Yet the rampant fear associated with

xenophobia is ultimately counter-productive, as this episode of a 70s kid show

rightly points out. If you close

yourself off, you also close yourself down to certain options, to new

solutions, and to improvements your life.

When you come from a closed place, everything – even learning – comes to a stop.

It’s not a healthy response to fear, even if it is, on some level,

understandable.

It’s

very interesting that Ark II chooses to tell this

particular story, about a place that has sealed itself off from the world and

in its insularity faces extinction. “By talking instead of fighting,” says

Jonah “we can move forward.”

In

terms of Ark II continuity and lore, this episode reveals that the Ark

II can fire a focused beam from its fore section, but the beam is still defined

as “a force field,” keeping in tune with the idea of self-defense and no aggressive

weaponry. Intriguingly, the force field

is also quite a limited device. In

trying to move heavy stones from the vehicle’s path, the force field’s power

grid short circuits…

Although

“The Balloon” carries a laudable message, it plays, at this point, as fairly

routine. The series is in something of a

rut, with tiny villages constantly being shown the error of their primitive

ways by the Ark II team. The

civilizations of the week – battling superstition (“The Slaves”), xenophobia (“The

Balloon”), cruelty to the weak (“The Rule”) and technophobia (“The Tank”) – are

a bit too predictable and one-note at this point. But the series is about to mix it up with

some infusions of more science-fictional elements, from robots and suspended animation to telepathy,

and that’s a good thing.

Next

Week: “The Mind Group”

Published on June 09, 2012 00:03

June 8, 2012

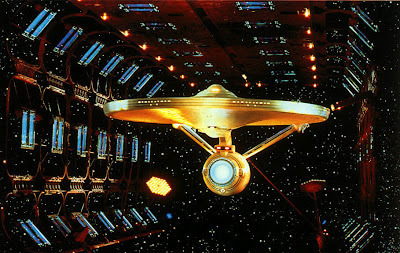

From the Archive: Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979)

"Why is any

object we don't understand always called a thing?"

- Dr. McCoy (DeForest

Kelley) in Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Directed by Robert Wise ( The Day The Earth

Stood Still [1951]), Run Silent, Run Deep [1958], The

Haunting [1963], Audrey Rose [1977]) and

produced by TV series creator and "Great Bird of the Galaxy" Gene

Roddenberry, this forty-five million dollar voyage of the starship Enterprise launched

a film series that has endured a whopping three decades plus.

Despite proving a box-office bonanza and the

father to ten cinematic successors of varying quality, Star Trek: The

Motion Picture remains today one of the most polarizing of the

film series entries.

The received wisdom on the Robert Wise film is

that it is dull, over-long, and entirely lacking in the sparkling character

relationships and dimensions that made the 1960s series such a beloved success

with fans worldwide.

It is likely you've heard all the derogatory

titles for the film too, from The Motionless Picture , to Spockalypse

Now , to Where Nomad Has Gone Before (a

reference to the episode "The Changeling.") Recently, even Leonard Nimoy derided the film as not being "real" Star Trek .

Conventional wisdom, however, isn't always

right. Among its many fine and enduring qualities, Star Trek: The

Motion Picture is undeniably the most cinematic of the Trek movie

series in scope and visualization.

And, on closer examination, the films features two very important elements that

many critics insist it lacks: a deliberate, symbolic character arc

(particularly in the case of Mr. Spock) and a valuable commentary on the

co-existence/symbiosis of man with his technology.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture also re-invents the visual texture of the franchise, fully

and authoritatively, transforming what Roddenberry himself once derided as

"the Des Moines Holiday Inn" look of the sixties TV series for

a post- Space:1999 , post- Star Wars world.

The central narrative of Star Trek: The Motion Picture is

clever and fascinating (and, as some may rightly insist, highly reminiscent of

various episodes of the TV series). Sometime in the 23rd century, a massive,

mysterious space cloud passes through the boundaries of Klingon territory and

destroys three battle cruisers while assuming a direct heading to Earth.

The only starship within interception range is

the U.S.S. Enterprise, a Constitution class starship just

completing an eighteen month re-fit and re-design. Admiral James T. Kirk

(William Shatner), Chief of Starfleet Operations, pulls strings and calls in

favors to be re-assigned as captain of the Enterprise, arrogantly

displacing the young, "untried" Captain, Will Decker (Stephen

Collins).

After departure from dry dock, the Enterprise faces severe

engine design difficulties of near-catastrophic proportion, but the timely

arrival of the half-Vulcan/half-human science officer, Mr. Spock (Leonard

Nimoy) resolves the problem. In the intervening years since the series,

however, the inscrutable Spock has become even more stoic and unemotional,

having attempted to purge all his remaining emotions in the Vulcan ritual

called Kolinahr.

Upon intercepting the vast space cloud, known

also as "the intruder," the Enterprise crew learns,

following a series of clues, that the colossal space vessel sheathed within the

cloud/power-field is actually an artificial intelligence, a living machine

called V'ger. And at the "heart" of V'Ger is a NASA Voyager probe

from the 20th century -- re-purposed by an advanced society of living machines

on the other side of the galaxy -- sent back to Earth to find God, it's

"Creator." In V'ger's quest to touch the Divine, Kirk, Spock and

Decker each find personal enlightenment, resolving their personal dilemmas and

also saving Earth from destruction.

"All Our Scans Are Being

Reflected Back..."

The creative team of producer Gene Roddenberry

(1921 - 1991) and director Robert Wise (1914 - 2005) consisted of two

individuals who had very distinct philosophical views about technology, and the

destination where technology was driving mankind.

In Roddenberry's case, we must countenance his

progressive concept of "Technology Unchained," the notion of

technology becoming both beautiful (rather than clunky and mechanical...) and

benign.

Man's machines, Roddenberry believed, would come to serve all the needs of the

species, thus freeing humanity from the age-old dilemmas of poverty, dwindling

resources, racial prejudice, hunger, territorial gain and war. This was an

optimistic vision of man and machine in harmony, one given even fuller voice

almost a decade later in Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987

- 1994).

By contrast, Robert Wise directed the

technological thriller, The Andromeda Strain (1971),

based on the best-selling Michael Crichton (1942-2008) novel about an alien

organism (or germ...) threatening all human life on Earth. Wise once stated

that The Andromeda Strain concerned "the first

crisis of the space age," a descriptor which permits us to see Star

Trek: The Motion Picture as a further meditation on a similar

theme, only representing a (much) later planetary crisis, one in the 23rd

century.

Wise also stated that technology -- particularly that on hand in

the subterranean Wildfire Laboratory -- was the "star" of The

Andromeda Strain.

In keeping with that motif, The

Andromeda Strain's opening credits consisted of a space-age

montage of technological symbols, from blueprints to graphs, to top secret

communiques. Think of it as a dot-matrix age Jackson Pollock.

In the same vein, the characters in the film

spoke in protean techno-babble on arcane subjects such as "Nutrient

24-5," "Red Kappa Phoenix Status," the "Odd Man

Hypothesis," "Sterile Conveyor Systems" and the like. In all,

Wise's 1970s sci-fi film represented a dedicated documentary-style approach,

one that never easily accommodated a "lay" audience. Instead, you

felt you were actually inside that underground complex alongside the Wildfire

team.

Most uniquely, however, the The

Andromeda Strain's climax concerned the pitfalls of technology: a

teletype/printer experienced an unnoticed paper jam at a very

inopportune moment. Some critics and film scholars have interpreted this

malfunction as Wise's explicit warning about relying too heavily on technology,

but the opposite was true. Had the printer worked as planned, one of the

scientists would have transmitted orders for a nuclear bomb detonation at an

infected site, a course of action that would have catalyzed and spread the

Andromeda germ.

The machine's paper jam gave the flawed human

being time to learn more, and re-consider the course of action. Given this

analysis, one can detect that Wise was, perhaps, agnostic on the subject of man

and technology, seeing both how it could prove a great tool, but also a great

danger.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture serves, in several ways, as an

unofficial "sequel" or heir to Wise's Andromeda Strain in

terms of both approach and philosophy. Of all the Star Trek films, The

Motion Picture is the only series installment to feature so many

lingering insert shots of technological read-outs and

schematics. For example we see a medical visualization of the Ilia Probe's

physiology, a representation of "a simple binary code" (radio

waves), "photic-sonar readings"(!) and several tacticals revealing Enterprise's approach

and entrance into the cloud.

These multitudinous

close-ups of computer graphics and read-outs not only enhance the notion of Enterprise as

working starship -- with several interfaces directly at our disposal (fostering

the documentary feel), -- but go a long way towards establishing the vital link

between technology and crew, a symbiosis, if you will.

A great deal of time is spent in the Motion Picture on

views of the crew gazing through the Enterprise's "technological" eye

or window on the universe, the view screen. In a film about the

combining of man and machine into a "new life-form," these moments

carry resonance and significance: they reveal man already traveling down that

road to symbiosis, relying on technology as his eyes, ears and (in the case of

the ship's computer...) key interpreter of data or external stimuli.

In Star Trek , the TV series, Spock often gazed into a hooded

library computer and we were denied access to what data he saw recorded inside

(save for the reflected blue illumination on his face). In later Treks ,

stellar cartography played a role, but the high-tech, colorful displays it

produced for crew members were not filmed as inserts. In other

words, we saw Picard and Data interpreting the data, and the

data itself. It's important, I believe, in Star Trek: The Motion

Picture that the data read-outs and view screen images are primarily

brought directly to our eyes without dramatis personae coming

between projector and percipient. For one thing, we feel as though we're

actually aboard a ship in space. For another, we're taking part in

that symbiosis of man and machine; we're interpreting the runes ourselves.

The underlying philosophy in Star Trek: The Motion Picture seems

to consist of an admonition that man and machine work best together integrated,

not when separated. V'Ger is a living machine who has "amassed" all

the knowledge of the universe, but is without the human capacity of

"faith," to "leap beyond logic," The machine (without human

input or touch...) is cold, and barren, and incapable of believing in other

realities (like the after-life) or other dimensions. Thus it is incomplete. Only

by joining with a human (Commander Decker), does V'Ger find a sense of

wholeness, of completion.

Kirk's journey is not entirely different. He views the Enterprise -- a machine

itself -- as almost a physical lover in this film. When Scotty takes Admiral

Kirk via a shuttle pod to inspect the Enterprise's re-designed exterior, Kirk

has the unmistakable look of a man sizing up a sexual conquest, not a starship

captain merely reporting to his new assignment. He avariciously sizes up the

"woman" in his life (and ships are always "she" aren't

they?). Like V'Ger after the union with Decker, Kirk ultimately finds a sense

of completion once he has "joined" with the starship Enterprise,

both metaphorically and literally. Once he is her captain again, Kirk is

complete.

Consider for a moment just how many times Star Trek: The Motion

Picture lingers upon the important act of a man entering -- or

connecting to -- a machine. We watch Kirk's shuttle pod

"dock" with Enterprise after a long, lingering examination of the

ship. We see Spock, in a thruster suit, "penetrate" -- in his words,

"the orifice" leading to the next interior "chamber"

of V'Ger. This terminology sounds very biological, doesn't it? Consider that

Spock next mentally-joins with V'Ger, utilizing a Vulcan mind-meld, yet another

form of symbiosis.

And finally, we see Decker and Ilia physically join with the V'ger Entity

during the film's climax. And make no mistake, that final act is

equated with physical reproduction explicitly in the film's text.

"Well, it's been a long time since I delivered a baby," McCoy notes

happily in the film's epilogue, and Kirk remarks on "the birth" of a

new life-form. They're talking about sex, about the union of two-life forms

creating a third, unique one.

Similarly, the journey of the Enterprise inside the giant

V'Ger cloud replicates the details of the human reproductive process, with the

final result proving identical: the birth of new life. In Star Trek:

The Motion Picture , man and machine mate. They join in symbiosis to

create something new, perhaps even as Spock notes, "the next step in our

own evolution."

While Star Trek films have traded explicitly in both allegory (particularly The

Undiscovered Country and the Cold War "bringing down the

Berlin Wall in Space" idea) and social commentary (consider

the environmental message of The Voyage Home ), Star

Trek: The Motion Picture is decidedly symbolic. That's

an important distinction.

The central images in the film all symbolize the reproductive, joining process.

Spock penetrates the V'Ger "orifice," to mentally join with a living

machine. Decker and Ilia (V'ger's surrogate) are mated in a light show that

some Paramount studio executives allegedly termed a "40 million dollar

fuck." And even the journey of the Enterprise (essentially

the male "sperm") through the fallopian tube-type interior of V'Ger

-- carrying its creative material (the human spirit in this case) to

the V'ger complex (ovum) -- reflects the overriding theme of

mating/joining/symbiosis.

So is technology a help

or a hindrance? For the Klingons,

destroyed in the film's first act, technology doesn't seem to help much. All

their elaborate technical read-outs and tracking sensors (again, shown in

dramatic insert shots) only permit them to watch the progress of their

annihilation down to the last detail; down to the last second.

On the Enterprise, technological attempts to understand V'ger are

constantly stymied by the living machine. "All scans are being reflected

back," Uhura notes in the film on more than one occasion, meaning that

V'Ger is re-directing the Enterprise's investigative entreaties back at

itself. This is a subtle indicator that the answers Kirk and the others

seek are held within themselves; in the gifts, contradictions and

essential nature of "carbon based life forms." They begin to key in

on this fact when Kirk and Spock assign Decker to awaken the human (er,

Deltan...) memory patterns of the Ilia Probe (a mechanism). The answer, they

come to understand, rests in the human equation, not in a technological assessment

of V'ger.

It's interesting to tally the scoreboard here. V'Ger (a machine) finds

"God" and evolves with the help of a human (Decker). Kirk finds his

peace with a machine (The Enterprise). Spock finds his answer about the meaning of life from a machine,

and that answer is an acceptance of humanity. Even Decker finds his

"peace" with a machine that replicates (down to the last detail) the

memory patterns of his lost beloved. Each of these main characters (Kirk,

Spock, V'Ger and Decker) are intricately involved with the story's main conceit:

the mating of man and machine; of "cold" knowledge and

"warm" human emotions.

"Our Own Human Weaknesses...and the Drive That Compels Us to Overcome Them..."

Despite protestations to the contrary, Star Trek: The Motion Picture is

a movie intrinsically, nay organically, about character, and

character development. In simple terms, the film's main characters (Kirk, Spock

and Decker) serve as the deliverer of human ideals to the cold, empty V'Ger

child so that it may "evolve." But in doing so, they also bring along

a lot of "foolish human emotions," as Dr. McCoy asserts at the film's

conclusion.

Captain Kirk begins the film, for instance, as a ruthless, single-minded

"my way or the highway" obsessive. We see his determination to

reclaim the "center seat" when he tells Commander Sonak at a space

port that he intends to be aboard the Enterprise following a meeting with

Admiral Nogura, Starfleet's top brass. We see it again when he rationalizes

displacing Decker, off-handedly noting that his "experience...five

years out there, facing unknowns like this one," make him the superior

commanding officer. The contradiction in that argument should be obvious. Are

different "unknowns" actually capable of being categorized? How does

Kirk know that Decker's history and experience won't prove superior in dealing

with this threat, the alien cloud? He doesn't: he just wants

what he wants.

And to some extent, the Enterprise (Kirk's other half, or

perhaps a representation of his id...) rebels against this egomaniacal version

of Kirk. Consider how much goes wrong on Enterprise when Kirk

is acting in this selfish mode. The transporters break down, killing two new

crewmembers. Kirk gets lost on his own ship and is discovered (in an

embarrassing moment) by Decker, the very man he replaced. Kirk "pushes"

his people too hard, forcing the Enterprise into warp speed

before it is ready, and in the process nearly destroys the ship in a wormhole.

He does so over the objections of Mr. Scott, Captain Decker and even Dr. McCoy.

This Kirk is all ego and selfishness, until he remembers the key to commanding

the Enterprise: listening to all viewpoints and making informed decisions. This

also happens to be the key in any male/female relationship. Just treat

her like a lady, Jim, and she'll always bring you home. This first

Kirk is too hungry, too grasping, too desperate to "re-connect" with

the Enterprise in anything but a physical way. Bones puts Kirk in his place,

but all the malfunctions of the Enterprise subtly (and symbolically) perform

the same function.

About half-way through

the film, Kirk is still learning this lesson in humility, as Decker notes that

as the vessel's executive officer, it's his responsibility to "provide

alternative" viewpoints. Kirk accepts that argument, but hasn't

internalized it. By the end of the film, he is actively listening to others

again, heeding Decker's request to join a landing party, and allowing Spock to

proceed when the curious half-Vulcan overrides his orders and steals a thruster

suit.

The familiar Kirk of Star Trek lore, the one who

develops a strategy based on hearing all viewpoints, slowly re-asserts itself

over the selfish one who wanted command and conquest of the Enterprise, and

nothing else. A journey that began in selfishness, ends in his

"unity" with the crew and ship, his acceptance and sense of joining

with those around him, a reflection of V'Ger's joining with the human

race. Kirk has, as he states, overcome human weakness.

Although Spock is only half-human, he undertakes much the same journey as Kirk

in the film. He returns to Starfleet because he has failed to purge himself of

human emotion and believes that an understanding of V'Ger will lead him to that

destination. McCoy fears that Spock -- like Kirk -- will put

his own personal interests ahead of the ship's. What Spock ultimately learns

from his encounter (mind-meld) with V'Ger is life changing for him. He

discovers that V'Ger has achieved what he seeks, "total logic." But

damningly, "total logic" doesn't make V'Ger happy. Thought patterns

of "exactingly perfect order" don't leave room for belief (in the

afterlife...), for the "simple feeling" of friendship Spock feels

towards Kirk, or much else.

For all V'Ger's knowledge, Spock realizes that the alien is "barren"

and "empty." Were Spock to pursue Kolinahr, he would end up the same

way. Spock's "human flaw," if we can call it that, is also one of

ego, his obsession with becoming the "perfect" Vulcan. In

embracing friendship with Kirk, in feeling his emotions (and even weeping, in

the film's extended version), Spock begins to embrace the emotions he has long

denied...and provides Kirk with the key to understanding V'Ger's psychology. He

would never have come to this epiphany had Spock not "joined" with

V'Ger in a mind-meld. And that puts us right back at the theme of symbiosis.

Decker (Stephen Collins) undergoes an interesting character arc too. He is a

young man who fears commitment and the responsibilities it brings. He left

Delta IV, Ilia's home wold without even saying goodbye to the woman he loved,

which is a pretty sleazy and avoidant thing to do. It might even be termed

"cowardice." In the end, Decker overcomes this "human

weakness" and joins with Ilia and V'Ger, saving the Earth, repairing his

relationship with Ilia, and adding the human component to V'Ger that the

machine life-form requires to "evolve."

When Kirk, Spock and McCoy return to the Enterprise, Kirk

explicitly asks if they have just witnessed the "birth of a new life

form." As I noted above, Spock's answer is that perhaps they have seen

"the next step" in their "own evolution." This is a

statement that is linked to the characters themselves. Though

Decker has physically evolved to another (higher...) dimension or plane of

existence, Kirk and Spock have evolved too. Kirk is suddenly gracious and

comfortable in his skin again instead of imperious and dictatorial. And Spock,

for the first time in his life, understands that that his human emotions carry

value, and augment his "whole" personhood.

To claim that there is little or no character development in Star

Trek: the Motion Picture is wrong-headed in the extreme. In some

fashion, this is surely the most important story of Mr. Spock's

"life," his final recognition of his "human" half and the

gifts it offers. When we cavalierly write off Star Trek: The Motion

Picture, we are also writing off Spock's new enlightenment.

This is An Almost Totally New Enterprise...

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan is

often termed the film that saved Star Trek , and there may

indeed be truth to that argument. Certainly, I love and admire that Nicholas

Meyer film. However, consider just how much material present in later Star

Trek originates directly from the re-invention of

the franchise in Star Trek: The Motion Picture .

Most notably, the Enterprise re-design and update -- featured

in the first six feature films -- is introduced in this Robert Wise film

(exteriors and interiors). This was also the first Star Trek production

to feature a "warp" distortion effect around the ship when it went

beyond light speed.

Also, the modern iteration of Klingons -- so beloved by Trek fans

today -- is introduced here, in The Motion Picture . Before

the Wise film, Klingons were swarthy guys with beards who talked about

Klingonese (in "The Trouble with Tribbles") but didn't actually speak

it. After Star Trek: The Motion Picture , the Klingons were

menacing aliens with ridges on their foreheads (and boy would Next

Gen go to town with THAT idea...), wearing convincing armor and

speaking their own language.

We can't forget, either that Star Trek: The Next Generation's very

theme song, as well as the Klingon theme featured in First Contact and

elsewhere -- were re-purposed from Jerry Goldsmith's brilliant soundtrack for Star

Trek: The Motion Picture.

There seems to be this weird belief among many

fans (and even Leonard Nimoy) that Star Trek: The Motion Picture doesn't

represent the best of Star Trek . While it is easy to see

that the film doesn't accent the humorous side of the Star Trek equation,

The Wise film does get so many things right. Most importantly, it captures the

Kirk/Spock friendship in simple, poignant terms (in a scene set in sickbay).

Imagine how easy it would have been for Gene Roddenberry -- just two years

after Star Wars -- to cow-tow to public opinion and

make a huge, empty action film with laser blasts and spaceships performing

barrel rolls. No one would have blamed him. I'll bet you a lot of fans would

have liked that story better.

Instead, Roddenberry took a much more difficult route. He maintained the

integrity of Star Trek and dramatized a story about

mankind's future, and the direction we could be heading (with man and machine

joined together, balancing weaknesses and sharing strengths). Some might

declare that the film actually attempts and fails to reach the profound quality

of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey . Certainly, I would agree The

Motion Picture is not an equal to that film. However, here's

another point of view: in Roddenberry's vision of man's evolution, it isn't

some mysterious, unknown alien who transforms us for the better. No, in the

universe of Star Trek, it's mankind playing a critical

part in his own evolution, taking the reins of his own destiny himself. We

aren't victims of an alien agenda unknown to us. We're standing tall, ready to

face what the universe throws at us. Somehow, this is more...noble.

In considering (or perhaps, re-considering....) Star Trek: The

Motion Picture, our mission ought to be the same as the Enterprise's: to

"intercept" and "investigate" this fascinating movie and

judge for ourselves if it is just the cosmic bore critics complained of, or

perhaps something a bit deeper.

Of all the Star Trek movies,

this is the one that shows us the most of the universe at large (Klingon

territory, Federation spaceships, Vulcan, Earth...), most closely follows the

creed of "discovering new life forms" from the series, and most makes

us feel like we're actually passengers aboard the Enterprise.

Perhaps we wouldn't want Star Trek to exist on this

elevated, cerebral plateau for long, since humor and action are indeed shorted.

Yet there's something intensely admirable about the fact that this careful,

somber, thematically-consistent, intelligent effort was Star

Trek's opening salvo in the blockbuster sweepstakes of the post- Star

Wars age. While others sought to imitate, Star Trek chose

its own path.

And that's how a movie franchise was born.

Published on June 08, 2012 04:07

Movie Trailer: Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979)

Published on June 08, 2012 00:03

June 7, 2012

Before Prometheus: Five Reasons Alien (1979) Endures

Ridley Scott’s Prometheus opens tomorrow

and my review of the new film will appear here on the blog the morning of Tuesday,

June 19th (so go see it before then so we can talk about it…).

But given the arrival of a 2012 movie that

connects explicitly to the Alien (1979) mythos, I realized that

today represents the proper time to go back and gaze at the reasons why the

original film is so terrific and influential.

Here are my five reasons why the original

Alien endures more than thirty years after its release.

1.

Revolutionary production and art design, translated into revolutionary sets,

costumes and miniatures.

Alien truly pushed the science-fiction “space”

film forward into a new realm of imagination.

Director Ridley Scott’s movie eschewed the stream-lined modernism and “neat,”

minimalist future-look of such films as Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

and Journey

to the Far Side of the Sun (1969) as well as TV programs like UFO

(1970) or Space: 1999 (1975 – 1977).

The film offered instead a world that was

grungy, messy and recognizable…both lived-in and dirty. It’s true that Star Wars (1977) represents

a crucial step in this direction, having created a universe that – in terms of visuals – suggests a rich

and storied past. But Alien

went whole hog into a world where coffee mugs rested on computer consoles, where

pornographic pin-ups were hung up beside work stations, and where characters

wore sneakers and ball caps when not asleep in cryo-tubes (or “freezers” in the

vernacular of the film).

This visual aesthetic has famously been

termed “space truckers,” and it’s indeed a crucial element of Alien’s

mystique and appeal. In director

Ridley Scott’s capable hands, outer space was not some glorious final frontier. Rather, it was just your monotonous,

unglamorous day-job. In this future, the

average blue collar space traveler still worked for the Man (Weyland-Yutani), and

was still trying to get his fair share of corporate wealth and make a living

wage. And he still made it through the day on coffee, cussing and swearing when

things break down.

Alien, which features a great and very

believable monster, would not have succeeded if the elements of the film that

involved “futuristic” mankind – his ships,

his clothes, his environs – did not reflect a reality the audience could

understand and readily identify with.

The recognizable world of the main characters, in fact, makes the alien

world all the more disturbing and frightening.

2.

The alien itself.

Perhaps this aspect of the film is the one

that is actually most difficult to reckon with today because we’ve seen the Alien

xenomorph in so many settings and films since the first film came

along. We’ve had three direct sequels,

plus two AVP movies, plus toys and comics involving the alien.

The notion of a monster attacking a

spaceship crew was not new, of course when Alien , written by the great Dan O’Bannon,

was produced. By that point -- as history-minded film reviewers are certain

to remind us -- we’d seen It! The Terror from Beyond Space

(1958), Bava’s Planet of the Vampires (1965) plus episodes of The

Outer Limits (“The Invisible Enemy”) and Space: 1999 (“Dragon’s

Domain”) that explored the trope, in many cases quite brilliantly.

But Alien represented a new horizon for “monsters”

because of the bio-organic designs of Swiss sculptor and painter H.R. Giger. This artist’s style had never been captured in

mainstream film before, and his work expressed a total (and perverse) blend of

human flesh and hard-edged machinery. In

short, the monster in Alien looked like nothing audiences

had ever before reckoned with, a fusion of distinctly unlike elements.

There’s more to it than that too.

Today we take this for granted, but Alien

proved so horrifying a film because the monster’s shape and appearance

were different every time we encountered it.

We now know the alien life cycle by rote: egg, face-hugger, chest-burster,

and adult. But when audiences first

reckoned with Scott’s movie in the last year of the 1970s, none of this

information was known. We had no idea what was coming, or how the alien was

taking shape. It seemed to be in a

constant state of flux…of becoming.

Again, all the stages of the lifecycle are

familiar today, but in 1979, the alien seemed like the cinema’s first legitimate

extra-terrestrial: a thing that changed and evolved into something ever-more

hideous each time we saw it. The title “Alien”

expresses this idea beautifully.

Watching the film for the first time, we really felt we had encountered

something not human, and not of this Earth.

Today, we’ve seen so many aliens and so many shape-shifters that we’re

inured to the concept. But Alien

got it right, in revolutionary fashion.

3.

Implications unexplored but suggested. This is the very reason

why we are getting Prometheus now. It’s

because Alien dramatized a complete and satisfying story of survival,

but more than that, brilliantly implied

a larger universe outside the context of the Nostromo’s last days.

Let’s gaze at the derelict ship that the

Nostromo finds on LV-426, which has become an important part of Prometheus’s

story-line. When we encounter it in Alien,

it is emitting a distress call (or actually, a warning: stay away). The characters Dallas, Lambert and Kane

investigate the ship and they see the dead pilot, the "space jockey"

with a torn-open chest. They also find a giant lower chamber, which must be a

cargo hold, given its dimensions and relative lack of instrumentation,

furniture, etc. This hold is filled

with alien eggs. The eggs are ensconced underneath a level of fog which

"reacts" when broken. What is this level of fog? Is it some kind of technology keeping the

eggs in stasis? Was it a safeguard to

keep the alien eggs dormant and the (odd) equivalent of the freezers we see on

the Nostromo? Who was meant to control it?

And then, of course, other questions are

raised. Who were these aliens

transporting the eggs? Why were they transporting alien eggs in the first place?

What became of the ship’s crew? Where

were they taking the eggs? And for what purpose

were they transporting this odd – and wholly

dangerous – cargo?

One big questioned unanswered: if a chest-burster broke out of the space

jockey’s chest, where was the adult alien when Dallas and the others arrived to

investigate? A possible answer is

that it had died out already, since in Scott’s original conception the alien

was to be like something akin to a butterfly, a “perfect” creature that only

could live for a few days

See how this film from 1979 is loaded with

implications and questions above-and-beyond the "ten little Indians"

template of an alien that kills astronauts on a spaceship? The deeper you delve,

the more interesting Alien becomes.

And again, this reflects our reality as

human beings, an important aspect of horror films. We are not privy to all the answers in

life. We don’t always know why things

happen, or what fate has in store for us. Some aspects of nature seem a mystery to us,

even with advanced science. The crew of

Nostromo likewise encounters a terrible mystery on LV-426, but that mystery is

largely left unexplored as the battle of survival begins.

4. It’s all about sex.

Alien is cherished and remembered by horror fans

for the gory chest-burster sequence featuring John Hurt. But the film also features one of the

creepiest off-screen deaths of all time, and a discarded idea (or hidden

implication) in the franchise. When last we see Lambert (Veronica Cartwright),

the xenomorph's tail is seen winding its nefarious way…up between her legs. Then, the film cuts suddenly to Ripley running

down a dark corridor, but we still hear Lambert panting and suffering and

some...inhuman moaning.

So what the hell is going on here? What is the alien doing to Lambert? Does

it -- by its very "perfect" nature -- boast some other form of

reproductive ability that it is practicing on her? Is it fulfilling some kind of

sexual desire?

Alien

possesses this queasy, uneasy sub-text involving our human sexuality. On the immediately-apparent surface

level, the film concerns a creature that can pervert our reproductive cycle for

its own ends. But underneath - if we peel

back the layers - there are moments in Scott's original that appear to

involve homosexuality, sexual repression, sexual stereotypes and more.

Consider that John Hurt's character Kane

becomes the first recipient of the alien's reproductive advances. Whisper-thin,

British, and sexually ambiguous, Kane is depicted - at one point in the film - wearing an undergarment that appears to

be a girdle; something that is distinctly "feminizing" to his

appearance.

Also, Kane lives the most dangerous (or is

it promiscuous?) life-style of anyone amongst the crew. He is the first to awake

from cryo-sleep, the first to suggest a walk to the derelict, and the only man

who goes down into the derelict’s egg chamber. He is well-acquainted with

danger as (stereotypically...) one might expect of a homosexual man circa 1979.

(Note: I said "stereotypically.”

The best

horror movies are about shattering decorum and transgressing against good taste

and Alien fits that bill.)

Soon in the film, it is Kane who is made

unwillingly receptive to an oral penetration: the insertion of the

face-hugger's "tube" down his throat...where it lays the

chest-buster. What emerges from this encounter is "Kane's son" (in

Ash’s terminology). But essentially, the alien forces poor Kane – possibly a homosexual male symbol -- to

act in the role he may be familiar with; that of being receptive to penetration.

Consider Ash and this character's sexual

underpinnings. He is actually a robot - a creature presumably incapable of

having sex -- and the film's subtext suggests that this inability, this repression of the sexual urge, has

made him a monster too. When Ash attacks Ripley late in the film, he rolls up a

pornographic magazine (surrounded by other examples of pornography) and

attempts to jam it down the woman’s throat...it's his penis surrogate. The implication of this particular act is that he can't do the same thing with

his penis, so Ash must use the magazine in its stead.

Later, Ash admits to the fact that he

"envies" the alien (penis envy?) and one has to wonder if it is because

the alien can sexually dominate others in a way that the disliked, often

dismissed Ash cannot manage.

Also note that when Ash is unable to

satisfy his repressed sexual desire for Ripley, the pressure literally causes

him to explode. The android blood is a

milky white, semen-like fluid. And it spurts everywhere, a catastrophic

ejaculation of monumental proportions. Ash, when confronted with his own

sexuality and inability to express it...can't hold his wad.

The most hyper-masculinized (again,

stereotypically-so) character in Alien is Parker (Yaphet Kotto), a black man

who brazenly discusses “eating pussy” during the scene leading up to the

chest-burster moment. He boasts an antagonistic, adversarial relationship with

Ripley, and is the character most often-seen carrying a weapon (a flame

thrower), a possible phallic symbol.

In another type of film, Parker might be

our hero. But here he dies because of

the stereotypical quality of male chivalry or machismo. Specifically, he won't

turn the flame thrower on the alien while a woman (Lambert) is in the line of

fire. The alien dispatches Parker quickly (mano e mano), perhaps

realizing he will never co-opt an alpha male like Parker to be his

"bitch;" at least not the way Kane was used.

As for Lambert, the most-traditionally

(and – bear with me -

stereotypically) female character in the film -- she gets raped by the alien as I noted above, presumably by the

xenomorph's phallic tail. Again, the alien has exploited a character's

biological/reproductive nature and used it to meets its own destructive,

perverse needs.

Which brings me to Ripley. Ripley is a

character written for a man but played by a woman (Sigourney Weaver). She is

the only survivor (along with Jones the Cat), of the alien's rampage on the

Nostromo, and there's a case that can be made that the alien cannot so easily

"tag" Ripley as either male or female, and that's why she survives. She

is perfect, like the alien is, a blend of all “human” qualities.

Kane is fey (possibly gay), Ash is a robot

(and hence not able to express sexuality in a "normal" way), Parker

is all macho man, and Lambert is a helpless damsel-in-distres...but Ripley is a

tall glass of water (practically an Amazon), and an authority figure (third in

command). She is also the only character who successfully balances common

sense, heroism, and competence.

Given this uncommon mix of stereotypically

male and female qualities, the alien is not quite sure how to either

"read" or "use" Ripley. In the final moments of the film,

it does make a decision. It recognizes Ripley - the best of humanity whether

male or female - as kindred; a

survivor. So it rides in secret with her aboard the shuttle Narcissus as they

escape the exploding Nostromo.

Note that the alien could likely kill

Ripley any time during that escape flight...but does not choose to do so. It

knows it is in safe hands with her, at least for the time being. It uses her

"competence," her skill (qualities of itself it recognizes in her?)

to escape destruction...again establishing its perfection.

Here, perfection might be measured by how

well it understands the enemy, the prey.

So, underneath the scares and underneath

the great design, what we get in Ridley Scott's Alien is the story of a monster that

exploits our 1970s views of biology and psychology; causing us (as viewers) to

re-examine -- perhaps even subconsciously -- the sexual stereotypes of the day.

The homosexual man is endangered first, the alpha males (Dallas and Parker) are

ineffective, the traditional "screaming" female gets exploited (not

rescued...), and the most "evolved" human, Ripley (along with another

perfect creature - a cat)

survives to fight another day.

The strange, spiky and sexual nature of Alien lurks just beneath the surface of the

film, and is noticeable even in the set design. Just take a long look at the

"opening" of the alien derelict.

Without being too graphic about this, it is pretty clearly a vagina.

And the chest-burster is pretty clearly

phallus-shaped. Ask yourself why. Sex, and -- sometimes discomfort with sex -- lurks at the heart of this horror film. This factor makes the film endlessly

interesting and worthy of a re-watch or debate.

5. Sigourney Weaver

as Ripley. Ripley is indisputably one of the cinema’s

greatest hero-warriors, but she’s more than that. She represents a critical change in how women

were conceived and written in horror and science fiction films.

Ripley

is simultaneously part of the “Final Girl” tradition and a crucial evolution of

the archetype. Ripley survives in the

film because she is smart and because she possesses insights the others do

not. She understands why regulations are

important, doesn’t succumb to emotion (regarding Dallas’s order to let Kane

back aboard the Nostromo), and she is extremely competent on the job. She takes command with authority, and is able

to understand the ramifications of her actions. She is tough, but never so much that we lose a

sense of her humanity. Male or female,

we all wish we could possess Ripley’s qualities.

Ripley

was Sigourney Weaver’s break-out role because the actress brought incredible commitment

and intensity to the role. Ripley

herself showed that the Final Girl did not need others (particularly men) to

rescue her, and that she could combat and even destroy the villain, not merely

survive to another day.

So,

Prometheus

opens tomorrow…and we already know that it will delve deep into the implications

of the Alien world.

I

wonder: will it create a monster as memorable as we first encountered in

1978? Will it feature a character as

forward-thinking as Ripley was? Will it boast visual canvas as revolutionary as

that which we saw in Scott’s horror film?

Will it carry a subtext beyond the surface story of “space horror?”

That’s

a pretty tall order, but I suspect that Prometheus will rise or fall not on

the new ground it breaks, but how well it subverts and plays with the expectations

we carry into the theater with us.

I

don’t know about you, but I can’t wait…

Published on June 07, 2012 00:03

June 6, 2012

Alien (1979) Trailer

Published on June 06, 2012 23:02

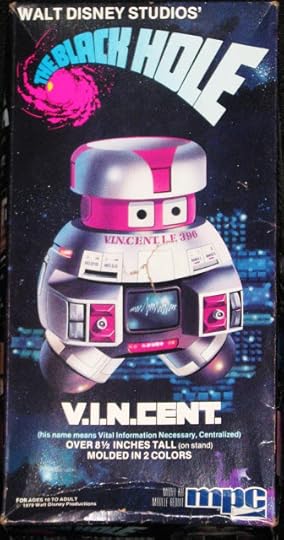

Memory Bank: Model Kits

I

grew up with model kits in the 1970s and 1980s, and I’ve always loved them.

And

neither of those qualities, incidentally, is the same thing as being good at

building model kits.

My

father is a truly great model-builder, but I don’t think I have ever possessed

the patience, coordination or necessary skill to build great models, and then

to paint them as well. Most of the time,

I just wanted to play with the kits immediately after assembly and begin my imaginative

adventures in the final frontier.

Still,

I have terrific childhood memories of sci-fi model kits from decades-past. Starting from the time I was probably five or

six, my father would purchase a model kit for me almost weekly from a hobby

shop in nearby Bloomfield, New Jersey, and spend Friday evening assembling it

for me.

I

would have to go to bed before he finished gluing and painting, but first thing

the next morning, I would spring up from bed and find the completed, painted – gorgeous -- model waiting for me on the

staircase leading up to the attic, which was right outside my bedroom.

It

was always a spectacular thing, to wake up Saturday morning to a new toy,

essentially. After breakfast and some

Saturday morning television, I was off to worlds of fantasy and excitement…

I

still remember my Dad’s work station in the house where I grew up on Clinton

Road in Glen Ridge. Behind the family

room sofa, he had a table (with wobbly legs…) and atop it was a giant gray

box. Inside that large flip-up box were

all of his modeling supplies, from utility knives to paints, to clamps and sand

paper.

In

a narrow space nearest to him, on the other side of the box, he had his

assembly area. I still remember that the

surface of the table was splotched and blotted with paint droplets. Sometimes, when I was very little, I would

sit at his table during the day and try to scratch the paint off with my

fingers, for some reason. I also have lots of memories of watching my Dad

working on my models at his “station,” occasionally looking up to catch what

was happening on Wonder Woman, The Incredible Hulk , or The Bionic Woman.

Since

I’ve always been a space adventure fan, the kits my father built for me were

when I was little were usually of the Star Trek or Space: 1999 variety:

starships and moon bases and the like.

That was where my tastes went, but my Dad was also a great builder of

his own kits, primarily tanks from the World War II era.

One

morning in the early 1970s that I’ll never forget, I found on those stairs outside

my room a completed Star Trek exploration set from AMT, consisting of the famous

communicator, phaser, and tricorder.

That kit really made my weekend, and I promptly took the Starfleet

equipment out on landing party duty (by the nearby train tracks and field,

where I played…).

I

also remember going to that same hobby shop in Bloomfield some time in 1978 -- before Battlestar

Galactica actually premiered on ABC -- and seeing on the shelves the

whole line of Monogram model kits from the series, including Colonial Vipers

and Cylon Raiders. At that point, I had

no idea what a “Colonial” or “Cylon” was, but I knew I had to have those

spaceship kits, and my father, as usual, indulged me.

Another

experience I recollect very clearly came in the winter of 1980 -- when I was very ill -- resting on the

sofa in our family room and watching the Lake Placid Winter Olympics while my

father built me an AMT Starship Enterprise.

As bad as I felt physically, I also felt good because I knew for certain

that the next morning I would wake up and have a beautiful Constitution class

starship to play with.

When

I became a pre-adolescent, my love of models didn’t abate. Now, my Dad and I would go out together on

Saturdays and hunt for hobby shops all over New Jersey and sometimes in New

York City. My Dad would always use the

opportunity of model kit “hunting” trips to talk to me about how I was doing in

school, how I was feeling, and on one occasion, he used our weekend ritual to

fill me in on the facts of life…

Over

the years of my childhood and adolescence I collected model kits from Star

Trek, Space: 1999, Planet of the Apes, Star Blazers, Battlestar Galactica, Buck

Rogers in the 25th Century, The Black Hole and other

franchises. Eventually, I started

building the models myself, but as I wrote above, I never was as good at the

task as my Dad was. I did build a

terrific Blue Thunder and Airwolf, when I went through my obsessive helicopter

phase in 1983-1984, however.

And

Andto this day, one of my all-time favorite models to build was “Gerry Anderson’s

Starcruiser One,” a kind of three in-one spaceship from Airfix that, in my

opinion, was an absolutely perfect spacecraft.

I have included with this post some photos of the model kits (boxes…) I’ve collected

over the years. I know it’s a wealthy

collector’s hobby today, and in 2012, there are toys available of the vast

majority of these spaceships. But there’s

still something incredibly special to me about a sci-fi model kit.

For

when I was young, there was no other way to play with the starship Enterprise,

except by AMT model kit.

Although

I suppose most Star Trek fans would say that the famous Federation starship

was constructed at the Naval Yards in Earth orbit, as a kid I knew with

certainty that the great vessel was built – with

a lot of love -- at my Dad’s work table in the family room.

Published on June 06, 2012 12:03

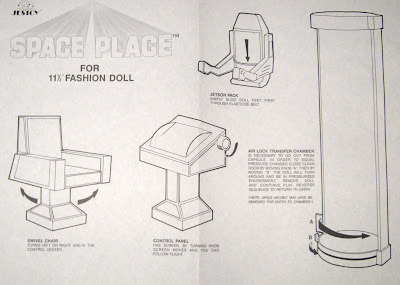

Collectible of the Week: Space Place (Jestoy; 1985)

Okay, so the box is heavy on pink, and this 1985 toy from Jestoy is technically called "Space Place for 11 1/2 Fashion Doll" (meaning Barbie), but this is one outer space play set I am nonetheless happy to keep in my collection.

The "Space Place" is the cockpit or control deck of a spaceship, and comes with "swivel chair," "control panel with moving screen," "jetison [sic] pack," "air lock transfer chamber," "simulated space capsule diarama [sic]," "space communicator," "video camera" and even "space play food."

Although the makers of the toy (in Hong Kong, apparently) couldn't spell worth a damn, they nonetheless created a very cool space deck, and one that actually fits the Mego

Star Trek

figures of the 1970s, or the

Space: 1999

figures from Mattel in the same time period.

Although the makers of the toy (in Hong Kong, apparently) couldn't spell worth a damn, they nonetheless created a very cool space deck, and one that actually fits the Mego

Star Trek

figures of the 1970s, or the

Space: 1999

figures from Mattel in the same time period. The control panel may be the coolest part of the toy. It boasts knobs on both sides which can change the space image "so you can follow flight." I'm not sure exactly what that means, but I suspect it has something to do with plotting a trajectory. The jettison pack has an elastic belt that can fit around most Meo-like figures, so they can go out on spacewalks. And the air lock transfer chamber is "necessary" if your action figures must "exit the chamber." The instructions offer detailed directions for equalizing air pressure for your astronaut (sold separately...).

I've written frequently in the past how I enjoy the generic or knock-off toys of the 1970s and 1980s, because they provide either alien locales for your franchise toys, or can become the hubs of new, imaginative play in a fresh universe. Despite being pretty in pink, the "Space Place" from Jestoy Ltd. fits the bill.

Published on June 06, 2012 00:03

June 5, 2012

Cloned from a Mutual Zygote: Carousel Stormtrooper

Published on June 05, 2012 21:01

The Star Trek Movie Matrix

Title

Earth

Under

attack

WMD deployed

TV series

Crew

-man

dies

Enterprise is

destroyed

Villain recurs from TV

Strange New Worlds explored

New Life-form encountered by Starfleet

officers

Time

Travel

Motion Picture

Intruder

Cloud

No

No

No

No

No

V’ger

No

Wrath of Khan

Not

directly

Genesis

Device

Mr.

Spock

No

Khan

No

Ceti

Eel

No

Search for Spock

No

No

No

Yes

Klingons

Genesis

Planet

No

No

Voyage Home

Whale

Probe

No

No

No

No

No

Probe

1986

Final Frontier

No

No

No

No

No

Sha

Ka Ree

God

No

Undiscovered Country

No

No

No

No

Klingons

No

No

No

Generations

No

Trilithium

device

Captain

Kirk

Yes

Lursa

and B’etor

No

No

No

First Contact

The

Borg

No

No

No

The

Borg

No

No

2063

Insurrection

No

Metaphasic

radiation

Harvester

No

No

No

No

No

No

Nemesis

Yes

Thalaron

Weapon

Lt.

Cmdr. Data

No

Romulans

No

No

No

Star Trek (2009)

Yes

Red

Matter

No

No

Romulans

No

No

Yes

Published on June 05, 2012 12:03

The Horror Lexicon #16 Female...Pulchritude

I

referred to this cliché as “the breast

part of the movie” in my books Horror Films of the 1980s and Horror Films of the 1990s .

And yes, this element of the horror lexicon is

proof-positive that the horror genre is not always high-minded or intellectual. Sometimes the form appeals to more basic instincts; Sometimes,

the first mission of horror is to exploit a fear or desire, and it’s foolish to

deny that this is the case.

But

absolutely without a doubt, the most common shot in all-of-the 1980s horror

cinema involves a young female taking off her blouse and bra for the camera. It’s almost a rite-of-passage for a prospective

“Scream Queen” of that era.

But why, you ask?

Some

critics might inform you that the numerous instances of female nudity in genre films arose because we

live in a sexist culture, and because young men – the dominant audience for horror films back in the 1980s -- wanted

to see it. Newsflash: men like looking at naked, attractive females. Women like seeing men too, but in the 1980s, it was mostly men making and green-lighting horror films.

Others

might point more directly to the specific conventions of the slasher sub-genre. And the slasher format is a deeply conservative form of horror concerning the

draconian price people pay when they step outside of moral and social traditions.

In

particular, “The Vice Precedes Slice-and-Dice” trope requires teens to act

badly before being killed by Jason or his ilk, and pre-marital sex is, of

course, a big no-no. The “Breast Part of

the Movie” or “Thanks for the Mammaries” convention is part-and-parcel of that

dynamic. The shirts come off, the sinnin’

begins…and then the killer shows up with a machete to put an end to all the

fun. Some may see this as sexist, but generally both participants in the sex-act get killed simultaneously, so I'm not sure that's the case.

Today,

the horror genre – which attracts a wider

female audience – has backed off quite a bit from the heyday of this cliché

in the 1980s. The genre has admirably focused instead on showcasing “final

girls” as intelligent, resourceful, courageous heroes. Even recent, tawdry fare such as Shark

Night (2012) eschewed the Breast Part of the Movie cliché. The trope was also mocked and satirized – and

treated as a tease -- in Kevin Williamson’s Scream (1996).

At

its most respectable, the trope actually can boast some iota of social value,

as it did in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971). There, in the early 1970s age of “bra burning,” there was

a question about the line of responsibility and where was it drawn. When lines of traditional behavior were

breached, how would the “old” guard react to new freedom?

By

contrast, one of the most exploitative examples of this convention occurs in Howling

II: Your Sister is a Werewolf (1986), which during its final, end-credits montage

features seventeen views of Sybil Danning ripping open her shirt and revealing

her…chest. Another movie that took the

trope to absurd new heights was Jim Wynorski’s vaseline-colored The Haunting of Morella

(1990).

You’ll

notice that, aside from this cliché, these two films don’t really have much going

for them in terms of quality.

I

don’t know that I need to write anything else about this particular convention

in the horror lexicon, and please forgive the illustrations for being

PG rated. But I don’t want my blog to be mistaken for an adult site. I already get linked to far too often on Russian porn sites (don't ask).

So…just use your imagination.

Here

is a (very) partial list of “the Breast Part of the Movie” appearances in

Horror Films

Straw

Dogs (1971),

Halloween

(1978), Phantasm (1979), Altered States (1980), The

Children (1980), Dressed to Kill (1980), Home

Sweet Home (1980) Humanoids from the Deep (1980), Maniac

(1980), Mother’s Day (1980), New Year’s Evil (1980), Night

School (1980), Nightmare City (1980), The

Silent Scream (1980), Terror Train (1980), American

Werewolf in London (1981), Dead and Buried (1981), The

Dorm that Dripped Blood (1981), Final Exam (1981), Friday

the 13th Part II (1981), Ghost Story (1981), Graduation

Day (1981), Halloween II

(1981), The Howling (1981), The Boogens (1982), The

Burning (1982), Evilspeak (1982), Humongous

(1982), Madman (1982), Curtains (1983), The

Evil Dead (1983), Mortuary (1983), Night Warning (1983), Pieces

(1983), The Black Room (1984), Crimes of Passion (1984), The

Initiation (1984), The Prey (1984), Biohazard

(1984), Friday the 13th: A New Beginning (1985), Fright

Night (1985), Though Shalt Not Kill…Except (1985),

Lifeforce

(1985), From Beyond (1986), Howling II (1986), Psycho

3 (1985), Slaughter High (1986), Vamp (1986), Witchboard (1986), Angel

Heart (1986), Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night 2 (1987),

Slumber

Party Massacre 2 (1987), Night of the Demons (1988), Sleepaway

Camp II: Unhappy Campers (1988), Edge of Sanity (1989), 976-Evil

(1989), Out of the Dark (1989), Society (1989), Baby Blood (1990), Demonia

(1990 ),

The Haunting of Morella (1990), Luther the Geek (1990), Maniac

Cop 2 (1990), Highway to Hell (1992), Prom

Night IV: Deliver Us from Evil (1992), Jason Goes to Hell

(1993), Phantasm III: Lord of the Dead (1993) Leprechaun 2 (1994), Embrace

of the Vampire (1995), Lord of Illusions (1995), Tales

from the Crypt: Demon Knight (1995), Bad Moon (1996), Cemetery

Man (1996), The Ugly (1998), Disturbing Behavior (1998), The

House on Haunted Hill (1999), The Ninth Gate (1999), Friday

the 13th (2009).

Published on June 05, 2012 09:12