John Kenneth Muir's Blog, page 17

September 7, 2024

50 Years Ago: Land of the Lost Theme Song and Intro

In September of 2024, the Sid and Marty Krofft live-action series Land of the Lost (1974 - 1977) celebrates its fiftieth anniversary.

I still remember tuning in to the first episode of the series and immediately falling in love with both the overall concept -- of a family "falling" into another world -- and the execution, which involved (at the time...) impressive stop-motion dinosaurs like Grumpy (a T-Rex), Big Alice (an allosaur), and Dopey (a brontosaur).

As you may recall, there was no "opening" episode of Land of the Lost featuring the Rick (Spencer Milligan), Holly (Kathy Coleman) and Will Marshall (Wesley Eure) in their "normal" life in California.

Instead, the inaugural episode, "Cha-Ka" (September 7, 1974), began with the Marshalls already ensconced in their strange new, prehistoric environs.

The series could begin so quickly with the action, in part, because of the splendid Land of the Lost introductory montage, which -- when paired with Linda Laurie's unforgettable theme song -- depicted the opening chapter of the Marshall saga.

In short, the theme and introductory montage shared with viewers everything they needed to know about how the Marshalls had become stranded in the pocket universe of Altrusia, and what threats they would face there.

"My song just recreates the experience of watching that fun show," Laurie told me in an interview several years ago.

As the Kroffts explained the series to Laurie for the first time, inspiration came to her. "I whipped out my guitar and started singing about this hole that leads to a place called the Land of the Lost. I repeated the word "lost" because you must have an echo if you're tumbling into the middle of the Earth. That's a requirement."

As the Land of the Lost montage commences, pictured below, we get a long-distance view of the Grand Canyon under golden sunlight.

The sun's rays are visible in frame, which suggests that this place -- home, for the Marshalls, essentially -- is a kind of veritable paradise.

The image is natural, or pastoral, and suggests peace and light. These qualities will contrast with the dangers of Altrusia, as we see further on.

The next frame finds the Marshalls -- Rick, Will and Holly -- in an inflatable raft, navigating a winding river.

Significantly, the family is at the center of the action here, and clustered tightly together in their small, confining craft.

This is an important blocking choice, because the family is at the center of the action in the entirety of the series as well, dependent on one another for survival and companionship. The blocking might have featured them in a line, one after the other, three in a row.

But to have them positioned as they are (in the image below) more aptly suggests a unit, or a family "together."

All the effects in this sequence, as you may note, are achieved using miniatures. They were created by art director and production designer Herman Zimmerman, a long-time veteran of the Star Trek franchise.

"I built the opening miniature of the series: the rapids," Mr Zimmerman told me in an interview.

"The show began with a group of young people, their father, and their raft, in Colorado, and I created this large miniature, maybe 25 to 35 feet long. I shot it on videotape with miniature figures and a life raft. And the letters that arose of the mist and announced the title Land of the Lost...I carved those."

In the next sequence of shots, we see the effects of the earthquakes on the mountains, the river, and the imperiled Marshalls.

I have always found this image to be one of the most fascinating in the introductory montage, because the opening of the mountain doesn't look random, or like an accident.

Instead, it looks like the mountains are parting at a pre-determined point, and that suggests, to me, anyway, an ancient portal...perhaps one built by extra-terrestrial (Altrusian?) or otherwise non-human hands.

They are in a new, long-unseen part of the river now, and about to go down a waterfall...

As the small raft careens down the colossal falls, the entire screen turns to white mist. Out of the mist comes a credit: Sid and Marty Krofft Present...

Now, the mist clears, and we get our series title, which appears to be carved out of the same mountain or rock-type as what we witnessed on the river, at the onset of the quake.

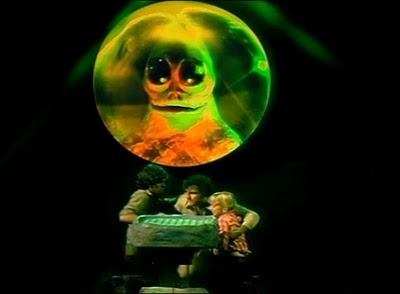

The Marshalls look up in terror, even as the creature -- shot from a menacing low-angle -- gazes down at them hungrily.

Next, we meet our series stars, as the Marshalls come to their senses...and run for their lives.

The T-Rex (Grumpy) pursues...

This cave becomes the ad-hoc "home" of the series, as the Marshalls move in and attempt to establish a new life there.

As the following images reveal, the humans are safe inside the cave, even from rampaging, hungry dinosaurs. None too pleased about this fact, Grumpy turns away from the cave -- and toward us -- and lets out an earth shattering roar.

Welcome to the land of the lost!

Below, the montage in action:

50 Years Ago: Land of the Lost (1974)

The year was 1974 B.C. (Before Cable). The place: NBC. The time: Saturday mornings.

Long before director Steven Spielberg and the late Michael Crichton ushered moviegoers through the gates of Jurassic Park , American children of the disco decade knew exactly where to get their fill of prehistoric action.

For three seasons -- from 1974 to 1976 -- every Saturday morning was reserved for the fantastic world of Sid and Marty Krofft's live action dinosaur romp, Land of the Lost.

Linda Laurie's series theme music has become part and parcel of the American pop culture landscape, and it acquaints viewers with the story of Land of the Lost better than any synopsis. To paraphrase, Rick Marshall (Spencer Milligan), Will (Wesley Eure) and Holly (Kathy Coleman), -- on a routine expedition -- experience the "greatest earthquake ever known." They plunge down a waterfall in the Grand Canyon and find themselves lost in a closed, prehistoric, pocket universe known to its bizarre denizens asThe Land of the Lost.

In this brave new world, the Marshalls encounter friends such as Cha-Ka, a brave little Pakuni ape-boy, and a baby brontosaur, Dopey. However, even as they attempt to return to their twentieth century home utilizing the Land of the Lost's strange crystal technology (housed in pyramidal stations termed "pylons"), the family grapples with a T-Rex named Grumpy, his distaff opponent, Big Alice, and the nefarious Sleestak.

Hissing lizard people, the Sleestak are actually the devolved remnants of the once-advanced Altrusian culture and the inhabitants of a mysterious lost city hewn out of stone. On more than one occasion, the Sleestak seek to feed the Marshalls to their (off-screen...) God, a bellowing monstrosity inhabiting a smoky pit.Though three Jurassic Park movies have deposited adults and kids in the path of rampaging dinosaurs, this was a revolutionary approach in 1973 when this TV initiative was formulated; "We were trying to find a habitat that could feature dinosaurs and a family...and those two entities together worked out to be a really good combination," Marty Krofft told me an interview conducted by telephone on January 11, 2001.

Krofft was also quick to credit his creative team. "Great things happen when you have imaginative people aboard, and we had Allan Foshko, who had worked with us on other things, and it was a very collaborative effort. You have a few nightmares and you come up with these wild characters and places."

Pilot

According to the late Allan Foshko, the series co-creator and then-vice-president in charge of new programming for the Kroffts, all of the dino-mite excitement commenced with Sid Krofft's long-standing affection for dinosaurs and dinosaur movies.

After that notion, however, it was up to Foshko to create the specifics. "You can't go back in time as easily as you can create something new, so I thought about the possibility of how we could transport a team back into the prehistoric era," Foshko told me.

"After some research, I discovered the Grand Canyon had been underwater at some time in history, and it is the most awesome of our natural monuments. There are so many things about the Grand Canyon we don't know, and one of which was that there could have been another land underneath it, because a stream had eaten its way down through all those layers of sediment for millions of years. And so it seemed to me a perfect setting."

From that notion, Foshko turned his attention to the characters who would visit this world. "I created the template for the characters: a family," Foshko reported. "Rick Marshall was a ranger who took care of the Grand Canyon, who watched out for forest fires and things like that. He and his son went on an outing one day and plunged into a waterfall that suddenly appeared, and they went crashing down in to the Land of the Lost...which I named. It seemed the perfect title."

Only after the pilot presentation was Holly Marshall added to the family. "They put in the little girl to appeal to a female audience," Foshko explained. "The network felt we needed that female aspect. Originally it was a father and son."

With the concept and characters created, the opportunity arose for Foshko to take his ideas from paper to stage. "I started to storyboard," he reported. "As it developed, I evolved a style of glass paintings from blue screens. I then shot actors separately, and put them into these painted settings. Someone once said that it was the cutting edge of special effects."

At this point, the series' actors were not yet cast, but the pilot featured unknown performers playing the father and son. "Once they were up against a matte, I could put anything around them," Foshko noted. The performers' voices were dubbed, and this presentation featured a voice-over narration.

"We started with a blank screen," Foshko sets the scene, "and then this voice came on [and said ]: 'More than a million years ago, there was a land of the lost...a land now uncovered.' After that, it all just fell into place."

"We did it for practically nothing," Foshko reported of the pilot's cost. "We did the storyboards and we shot it privately, with the company that would get the job if it became a series. But it was that pilot that sold the show...[T]he network brought in people for preview screenings and the response was so strong that we proceeded with the series."

"The pilot had the feel of Alice in Wonderland or Journey to the Center of the Eart h, with these people falling into another world," Foshko remembered with enthusiasm. "The story just flowed, and with these hand-painted storyboards and collages, it was an unusual approach to doing this presentation. We had music and special effects and all kinds of magic. For TV, it was revolutionary."

For Foshko, the pilot represented the apex of his work on Land of the Lost. "David Gerrold came in thereafter [as story editor] and I was not involved in certain things, such as the creation of the Sleestaks," he notes. "I had some input as the series continued, but I wanted to do the show with miniatures and rear projection and save a whole kaboodle of money, but the Kroffts preferred to use the time-honored sound stage [approach] and build the whole sets. I moved on, and started to work on other projects."

Despite the parting of the ways, Foshko remembered his collaboration with the Kroffts in purely positive terms. "They were instrumental in creating Land of the Lost and working with them was a pleasure. I believe the shows which take you out of the present and put you into a magical land will always be successful. You know, special effects movies are more popular today than ever, but this was done at a time when no one had really conceived of such thing [on a continuing basis]. I'm very proud to have had a hand in creating the concept of Land of the Lost ."

Pre-Production

After the Land of the Lost pilot was created, it was a job for the Kroffts (veterans of The Bugaloos , Liddsville, H.R. Pufnstuf ) to prepare the weekly Saturday morning series for NBC.

Linda Laurie, musician and composer, recalled for me that fertile period with enthusiasm: "The Kroffts had done these amazing puppet shows that kept going and going, and were known world-wide. They were branching deeper into television. That's when Foskho brought Sid Krofft to meet me. We all liked each other very much and giggled and scratched and laughed...I just thought they were all magical people."

"Then they explained the series to me. I watched them sit there and act out this crazy story about Marshall, Will and Holly, and then I whipped out my guitar and started singing about this hole that leads to a place called the Land of the Lost. I repeated the word "lost" because you must have an echo if you're tumbling into the middle of the Earth. That's a requirement," she laughs.

When Laurie visited the Krofft Studios in the Buena Vista area of Burbank, she was amazed at the level of imagination going into the creation of the props and creatures of Land of the Lost.

"With that series, you could not imagine a more exciting team around you, right down to every guy who painted fake rocks and made masks. Every single person was like a munchkin. And if you ever met Sid, you'd be sure he was a munchkin too. I think the Kroffts were moving to a level of experience where they were on the cutting edge of where children were going. They knew it was time to do a live-action adventure on Saturday morning."

"There was so much enthusiasm. I got to work with Jimmie Haskell, the arranger on the show...and he's probably one of the most extraordinary men in the business. Our team was wonderful, and every one of those people I worked with was magic. They aren't angels, mind you. They're nutcases...but wonderful nutcases. We call came out of the 60s nuts...but creative ones. Nobody was mean-spirited, everybody was giving, and people like the Kroffts lived off of fantasies and made fantasies come true. My song just recreates the experience of watching that fun show."

Albert Tenzer served as executive producer on Land of the Lost , and it was his job, as he recalled it, to deal with life and death financial decisions. "And, as you may know," he quipped, "every TV series was a life-and-death situation....I was basically the chief administrative officer, responsible for the relationship with NBC, the contract negotiations, the budget, and the organization of the production. I also oversaw interaction with the production group that was responsible for the special effects."

By Tenzer's estimation, the budget for Land of the Lost was approximately $400,000 to 500,000 dollars an episode. "My objective was to make sure that we didn't go over budget, but I don't recall the exact number. I do know it was our job to live within whatever amount we were given."

Tenzer was also involved in the creative end of the show. "I knew the creative people and I sat in on creative meetings. I knew what was going on. It was a much simpler kind of life than it is now. Today, there are layers of bureaucracy..."

Sets

With memorable music describing the series' central premise, and Tenzer keeping an eye on the bottom line, it was up to young art director Herman Zimmerman, now a veteran of several Star Trek film and television series, to visualize it. "I was hired to work on a new series Land of the Lost , because I had been working for NBC and a place called Hollywood Video Center," he told me.

"There, I met a gentleman who was hired by Sid and Marty Krofft to be a unit production manager and producer. That fellow recommended me to the Kroffts. They had already hired a sketch artist named Mentor Hubner to do some illustrations, and the Kroffts showed me some of those illustrations and asked me if I'd be interested in turning an existing set into the jungle landscape for Land of the Lost . I went over to Stage 5 at Sam Goldwyn Studios to look at the existing sets for Sigmund and the Sea Monster . In any case, that set was made entirely out of foam on wooden substructures and the foam was flame resistant till about three months old. The day I went to the studio to look at the set, it burned down."

"It was one of the worst stage fires in Hollywood, right there at Stage 5 on the Goldwyn Lot," Zimmerman recalls. "It was quite an experience because the assistant director went to the cast and crew and said "the effect you see on the back of the set is not an effect. Please leave the stage as fast as possible." A minute or so later, the ceiling of the studio collapsed. It spread that quickly. I had never seen a major fire, and this was a major fire, believe me. The ceiling caved in, [and] the floors with all the sets and TV cameras fell through the floor into the basement. It was incredible. I went home and figured that my job with the Kroffts was probably not going to happen since this was the set I was assigned to revamp for Land of the Lost, and it hadn't survived the fire."

The setback, however, proved temporary according to Zimmerman. "The Kroffts called me up the next week and I went to their offices for a meeting. They showed me pictures of the set and asked me to reproduce it in four weeks...which was almost impossible to do. I wanted the job, so I said, of course, I could do it. So first I re-designed Sigmund and the Sea Monsters , which had those undersea caves, and the idea was to turn those sets into those for Land of the Lost ."

"We went over to another studio, called Hollywood General. We took two sound stages that had an adjoining door and built Land of the Lost from one stage to the other," Zimmerman explains. "It was a huge set. Then I went to MGM and bought jungle backings and hung them up, and then used a company called Walter Allen Plant Rentals for the tropical flora. I bought a number of these little islands to put foliage on. And we used them to make different jungle pathways. It was a constant re-vamping of the same space to create different locales, and different kinds of science fiction objects to go with it."

Land of the Lost's stone caves were made out of "the same stuff you use to build a swimming pool," Zimmerman reveals. "We put steel mesh over wooden frames, and over that was solid plaster. They did Land of the Lost for three seasons, and at the end of that time, the plaster had hardened. When we went to strike the sets at the end of the show's run, we had to get a wrecking ball to destroy the caves, and take out the sets in a few very heavy pieces."

Zimmerman's other contributions have become sort of Land of the Lost trademarks. "I built the opening miniature of the series: the rapids," he notes. "The show began with a group of young people, their father, and their raft, in Colorado, and I created this a large miniature, probably 25 to 35 feet long. I shot it on videotape with miniature figures and a life raft. And the letters that arose out of the mist and announced the title Land of the Lost? I carved those personally."

Make-up and Monsters

Another young talent (and graduate of the Star Trek saga in recent years ), is make-up artist Michael Westmore, whom I also interviewed in early 2001. He landed an equally difficult assignment during the protean stages of Land of the Lost.

"I inherited a conceptual sketch of the Sleestaks. It was my job to translate it into three dimensions and color," Westmore told me. "The Sleestak were to be a prehistoric species. Since we were putting men into these costumes, the Sleestaks had to have two arms and two legs. And we wanted to make them fast and inexpensively, but also look like something you wouldn't be familiar with. And they didn't have to talk...which was a great advantage."

And though this strange pocket universe was to feature a whole race of the nefarious creatures, the series budget could only accommodate the creation of three costumes.

To produce the Sleestak, Westmore went to extraordinary lengths. "I had three wet suits made with a zipper up the back. The actors would stand inside them and I had to attach this yellow stomach plate and a big cookie-sheet of scales that would be applied one at a time."

As the late Walker Edmiston, who played the recurring role of the friendly Sleestak, Enik, told me, the Westmore-created suits were not very comfortable.

"As soon as I was in costume, those big eyes would start to fog up, so I couldn't read any cue sheets or prompters," said Edmiston. "Also, they hung this tiny microphone on the bridge of my nose, and if I spoke too loudly, the sound men would experience this deafening feedback. After wearing the costume for hours, I could pull open the sleeve and sweat would just pour out."

On one hair-raising occasion, the production team believed Edmiston was pulling a prank by pretending to be asleep on the set, when in fact he had passed out from the heat.

Third season producer, Jon Kubichan, recalled the Sleestak and the problems they generated. The creatures were all portrayed by over-sized, future NBA stars such as William Laimbeer, and were difficult to manage in costume. "It was really funny, because these giant basketball players were wearing six-inch platform shoes inside their wet suits. After a short time under the hot stage lights, their feet would sweat and they would slip and stumble like crazy. It was hard to make the Sleestak menacing because they were so clumsy."

"They were all basically All-American caliber basketball players," Westmore told me. "USC was trying to get them to go there, and one of them, David Greenwood, ended up going to UCLA and the pros. William Laimbeer went to the Detroit Pistons."

Outfitting giant creatures like the Sleestak was a difficult -- and daily -- job. "We had a wardrobe mistress, and there was this guy -- the male wardrobe person. It wasn't my job to help get the performers into the costumes, but since I made the darned things, they needed an extra hand. If I wasn't having to put the Pakuni together, I'd help the wardrobe people. Since there were three suits, each one of us would take on to help out."

Enik, the friendly Altrusian, posed his own set of difficulties for Westmore. Unlike the other Sleestak, he had to speak. "His mouth didn't move much," Westmore explains. "It wasn't articulated with machinery like it would be today. If it moved, what I would have done is added a piece of rubber in the chin area so when Walker Edmiston opened his mouth, it would move the lips. It wouldn't be the upper lip that would move, if you look real closely, it was just the lower lip."

Enik also was a different color from his Sleestak cousins. "The whole idea was that Enik was more intelligent than the other Sleestak, and Walter Edmiston was much shorter than the basketball players, so instead of making it look like we had a midget version of the green guys, it was a productin decision to paint him a different color. We went with beige and red eyes as opposed to green with black eyes. His hands were also smaller and tighter, so that Walter could actually grasp things. The other Sleestaks had these giant claws. I still have one of those molds left."

The other resident species living in the Land of the Lost was the aforementioned Pakuni, small "missing link"-type ape-man creature. As Westmore told me, Cha-Ka and his brethren came from an unusual source.

"Well, I had done a movie called Skullduggery (1970) starring Burt Reynolds and these furry little people. I was involved in going to Hong Kong to get the suits manufactured. After the film was finished, Universal had a whole bunch of these suits left over, so the Kroffts were able to buy three of them for Land of the Lost. Then I took and made the rubber head -- which looked like a Neanderthal brow -- and glued hair all over it to match the suits. So when the actors came in play the Pakuni, all I had to do was make-up the lower-half of their faces, from underneath their eyes down, and then their hands. Then I would slip their head appliances on, tack it down to their eyes, and then comb it so it would match the suit. Then it was over. It was very quick make-up."

Today, Westmore still has the last Sleestak head in his possession. "It's tucked away here somewhere," he told me. "I took one and filled it with urethane so the rubber has kind of rotten off outside of it, and given it this interesting texture. But I still have a solid chunk of Sleestak tucked away in a box somewhere..."

Series Bible and Stories

Visualizing two "alien" races wasn't Land of the Lost's only challenge. "The amount of effort going into creating the series was incredible," affirms Robert Lally, who directed a dozen episodes of the season during its first and second season.

"A PhD in linguistics, Victoria Fromkin, invented the Pakuini language, and there was a very specific Bible of how the Land of the Lost operated...and you couldn't violate those rules." In this case that Bible was written by the legendary creator of Star Trek's tribbles, award-winning science fiction author David Gerrold.

Writer Joyce Perry, who penned two episodes of Land of the Lost in its freshman and sophomore seasons ("Stone Soup" and "The Longest Day"), was impressed with story editor David Gerrold and his attempts to keep the prehistoric world of the series consistent from episode to episode.

"I'd seen the show and had some ideas,' Perry remembers of her introduction to the series. "So they saw me, we talked, I got to see the Bible, and I sold them my first story ("Stone Soup"). I worked everything out with David. He's the kind of person that you can bring ideas to, you start kicking them around, and by the time you're finished - you've discussed a hundred things. He's very, very creative and very smart. It was a pleasure working with a story editor like David because he not only writes science fiction, he loves science fiction. That's a little different than working with your typical story editor."

When asked specifically about the Land of the Lost series bible, Perry recalls only that it was a 'synopsis of episodes, the general ideas of the series, that kind of thing. "I remember that I loved the concept of the show and thought it was fun."

On both of her episodes, Perry recalls that her scripts went through a series of permutations. "David was very particular and I believe Dick Morgan [second season story editor] was too. I did a second draft for both of them, and they insisted things were done right."

Linda Laurie adds that the Kroffts had an edict to be obeyed at all times. "Don't patronize children. We were to take them on a ride, but never talk down to them."

That mantra was part of the reason why episodes were written by the likes of TV and science fiction veterans such as Dorothy Fontana, Walter Koenig, Larry Niven, Norman Spinrad and Theodore Sturgeon. The series may have aired on Saturday mornings, but each adventure was designed to be provocative, illuminating entertainment. Episodes featured time paradoxes ("Circle," "Elsewhen," "The Stranger"), doppelgangers ("Split Personality"), possession ("The Possession") and other solid, adult genre concepts.

More than that even, various episodes featured what today's audience would surely recognize as a distinct environmental bent. In other words, some episodes involved the Marshalls hammering out an environmental balance in the land of the lost between themselves, the Sleestak and the Pakuni. Often, the Marshalls were tasked with setting right environmental problems in their new home ("Skylons," "One of Our Pylons is Missing.")

Dorothy Fontana, one of science fiction television's finest and most legendary writers, also contributed a story in Land of the Lost's first season, titled "Elsewhen." It depicted young Holly Marshall being visited by a grown-up future self.

"The idea had been on my mind that it would be nice to know things as children that we do as adults," Fontana told me. "They [the producers] wanted to do a Holly story because they didn't have too many. So Holly's adult self came back to give her young self a warning, which was kind of like ''if I knew then what I know now...'

Keeping with the adult tenor of the show, and the Krofft's mantra never to talk down to children, the episode seemed pretty heavy, especially because the older Holly implied that young Holly would someday "lose" both her father and brother in the Land of the Lost, and be forced to cope with life there by herself.

"I have two brothers, and my mother was alive when I wrote that show," Fontana remembers. "But I was exploring the idea of what could happen if you lost those people in your life that you care about. In many ways, you're out in the world alone, and you have to be prepared for that."

Director Bob Lally remembers that there was "a fair amount of latitude" shooting the scripts. "A script is a wonderful thing on a piece of paper, but when you try to put it on its legs and take up three dimensional space, some things change. I don't mean that you change the story, but you might be changing lines, or you might find out that the actors aren't comfortable with the construction of certain sentences. We had a fair amount of latitude making those changes on the spot. If it was a major story point, we'd have to go back to the story editor and say 'hey, this isn't consistent with what we did yesterday.'"

In those cases, Lally recalled working with Dick Morgan more than David Gerrold. "Whenever I had a problem with a specific story point, I went to Dick. I'll say this: I thought the stories were good. There were some brilliant people writing for that series. One of them was Walter Koenig, Chekov from Star Trek ."

Koenig's episode was "The Stranger," the very episode that introduced Enik to the program. "I remember we gave it ["The Stranger"] a bit more attention," Lally explained. "When you're working on a series and you have a guest coming in who is going to be a recurring character, you've got to develop that character. You have to take time to make him seem more three dimensional."

Spencer Milligan, who played the Marshall patriarch, also had praise for the story editors. "Well, David Gerrold and Dick Morgan were the story editors and they were very efficient hard workers. In general, I did like the scripts when I was on the show. There's always room to do a little bit more, and always a desire to improve. We were shooting two shows a week, and I think that everybody worked hard to bring the highest quality possible in terms of those circumstances."

Acting and Shooting

In addition to its solid, thoughtful stories, Zimmerman speculates that Land of the Lost might have been so popular for another reason. "On Land of the Lost , it may be the actors as much as the writing that gave it such charm. They were great."

"It was a good group," director Lally told me. "Spencer Milligan is a very competent, very serious actor. You can't approach a show like that unless you take it seriously. You can't go in and do some kind of campy thing. Spencer looked at the show very studiously and he read the scripts with a serious eye. We had many discussions on the set about how things were going to play out, and what the relationships were."

Spencer Milligan became so identified with his role as Rick Marshall that he was still being recognized as patriarch Rick Marshall when I interviewed him by phone early in 2001, a fact he found both amazing and rewarding. "Though Marshall was a stoic character, he was capable of a full range of emotions and audiences connected with that," Milligan told me. "He was a father-figure who cared about his children and their behavior...and that's something we don't often see today."

Director Lally also enjoyed working with Edmiston. "Oh, he was a voice man of long experience. His credits could probably fill an encylopedia. He could do anything you wanted him to, and he brought a lot to the table on his own. You could just give him the script and he would come up with something more than acceptable. He was very receptive to direction and put a lot of character into his readings."

Edmiston liked his character, Enik, but felt that the Altrusion intellectual was not as well-rounded as he might have been. "I thought Enik was kind of funny. He was such an emotional dead-head.; You know, Will would run into a cave and shout at Enik, 'Dad is hanging by his thumbs over the pit and you've got to save him!!!'Well, Enik would reply, deadpan, 'Do not disturb me, Will Marshall, I'm searching for the vortex back to my time.' He wasn't a big help. He didn't have much humor, that's why they literally wrote the script "Downstream" for me."

In that episode, Edmiston was permitted to shed his cumbersome Sleestak costume and portray a century-old Civil War veteran trapped in the Land of the Lost. "Now that old codger was really wild...he drank fermented fish juice." Edmiston remembers with glee. "They [the set designers] did a great job with the caves and building the stream, where we would actually get in the water. They took a large pool and planted it with grass mats all around, and it looked just like we were going down a river at night. And there wasn't a tremendous budget. We were limited."

Director Lally has high regards not only for Edmiston and Milligan but for the young stars of Land of the Lost as well, Wesley Eure and Kathy Coleman.

In particular, he highlights his experience with them on one particularly difficult episode. "We were doing a show ("Album") that involved Will and Holly walking into a grotto and seeing their dead mother. They were supposed to have gone to this strange world and they miss her mother, and since they're children, they're supposed to be very emotional."

"We shot it once and it wasn't working. So we decided to play a little game with them. We worked really fast in those days, and I didn't have time to do a lot of fancy internalizing and so forth, but I took the two of them aside, behind the set, and we talked for quite a while.; What I said to Kathy, who was really having trouble with it, was 'you have to think of something in your past that was a very sad thing. Ever have a dog or a cat?' She said she did, so I asked her to visualize the animal being struck by a car. As you can imagine, Kathy was quite upset, but I assured her the pet was fine. Then I said I wanted her to understand how she felt when I told her about her cat dying. Then I told her that when she walked into that room that was the emotion I wanted to see on her face. Well, we went back inside, everyone was quiet, and I called action. The take was absolutely brilliant, on both of their parts. When we finished shooting, we went behind the set and hugged each other."

Despite such bonding moments, acting in a TV series that featured so many complex special effects was no picnic. Specifically, Land of the Lost utilized a now-archaic (but then new-fangled...) time-consuming technology called chroma-key that blended the live action footage of the actors with the stop motion photography of the show's lumbering dinosaurs.

"We worked on a completely empty stage." Edmiston reveals of the process. "When we had to walk down the path, the crew laid down little poker chips that were the same color as the background, so we could feel through our shoes where we were supposed to walk."

Milligan found the chroma-key frustrating. "There was nothing to look at. The crew would say, 'look over there - that's where Grumpy is' - but it was difficult to visualize. We all hated the chroma-key. When we knew it was coming, we'd say, uh oh, it's a blue day."

Lally had extensive experience with chroma-key before directing the series and knew it was a problematic technique. "It required a great deal of preparation and a skilled crew. The scenes had to be properly lit, colors had to be adjusted and wardrobe had to be coordinated so certain colors would not fade into the background. It was a lot of technical detail work. And in addition you have to work with actors who are capable of looking up at a blank wall and appearing terrified because there's an imaginary dinosaur there."

But even the blue days had a lighter side, as Edmiston remembered.

"Once Spencer threw this spear at a T-Rex and it stuck in the blue backdrop. When you combined the footage, the spear lanced the dinosaur's shoulder. We looked at the monitor and the crew said we couldn't have planned it that way in a million years.But then these two women from the network came on the set and said 'oh no, you can't show that! It's injuring the animal!' Spencer and I were stunned. It was a dinosaur for goodness sake!"

Land of the Lost's budgetary limitations also raised problems. Though the series' standing sets stretched across two studio buildings and included much of the Marshalls' cave shelter, the production could not afford more than one make-up artist. Westmore, the man on the spot, had a very busy tenure. "I went to work in the morning, made-up Holly, Will and Marshall, put together three Pakuni and then got three Sleestak into suits!"

Zimmerman likewise feels the low budget resulted in a hectic pace and some corner-cutting. "Saturday morning TV was not blessed with much money, so we built all the Sleestak caves out of heavy-duty tin foil. A good bit of my time was spent repairing holes in the foil when someone leaned against it and tore it open."

The Third Season

Not long after its premiere, Land of the Lost became a monster hit, the most popular show on NBC's Saturday schedule. Nonetheless, a series of changes were to come in the third season. Spencer Milligan departed from the show over a salary dispute, and was consequently replaced by Ron Harper (of TV's short-lived 1974 Planet of the Apes series) as Rick Marshall's brother Jack, who happened to fall into the Land of the Lost just as Marshall was falling out.

"That all came down to -- as everything does -- not being able to work out a financial arrangement that was acceptable to everyone," Mr. Milligan told me. "I had other opportunities awaiting me, so I opted to leave."

It was a difficult decision, and Milligan still remembered breaking the news to his young cast-mates. "I talked to them on the phone, but I didn't tell them any of the details about why I left. I think they were quite upset."

The late Sam Roeca, veteran of the animated series Valley of the Dinosaurs , signed on as the Land of the Lost third season story editor, and producer Jon Kubichan became the series' new producer.

"The first thing that Sam and I did was watch all the episodes," Kubichan explains. "I wanted the series to be more fun and do something in every episode that was instructive in terms of science."

Roeca was on the same page and shared a mutual enthusiasm for mythology with Kubichan. Together, the new team sought to present in each installment "something from the past, from some literature or children's narrative." This shift in focus resulted in a third season that saw the Marshalls grapple with mythological creatures such as Medusa, The Flying Dutchman, a unicorn, a fire-breathing dragon and the yeti.

A primary concern for Kubichan in the third season was the series' look. "When I came aboard, some incredible footage had not been used. I wanted to use it, so every show didn't look so much alike. There was this wild panorama of the Land of the Lost with all three of its moons, panning left to right, and I don't think it had ever been seen."

Unfortunately, the third season revamp proved controversial with longtime fans who felt that new episodes contradicted material presented during Gerrold's tenure.

In particular, the first two seasons had defined the land of the lost as a closed pocket universe from which escape was not possible unless balance was maintained ("Circle"). For every person who came in, another had to leave. In the third year, this concept was dropped and a balloonist, a Civil War soldier and other guests came and went, sometimes merely by flying away or by navigating a river (which in earlier years had been depicted as circular, and thus a dead end, in episodes such as "Downstream").

Ron Harper did well as Uncle Jack, but his character never quite fit in. "Well, Ron Harper came in under very dire circumstances, to replace someone who had been on the show for two seasons," noted Spencer Milligan. "Any time you do that, it's a tough job. At best it's a tough gig; we've all had to replace people at times because of illness or whatever, and the audience is waiting for the other person to be there and you show up. You're under scrutiny. Ron did a terrific job, considering the situation he had to deal with."

Though the ratings remained high during the third season, Land of the Lost was cancelled in 1976. Executive Producer Albert Tenzer explains what happened. "Saturday morning was an important revenue source for NBC, and they were happy with the show.; But right around that time, they began airing sports on Saturdays and so the morning became far less critical. Also, it was expensive to broadcast Land of the Lost reruns, unlike cartoons, because you had to pay royalties to the live-action performers. Simply put, there were less expensive alternatives."

Of Land of the Lost's untimely cancellation, Roeca noted that "there is an algebraic factor determining the life and death of a series: how much will the build-up of residuals affect the profit margin?" In the case of Land of the Lost, that equation was more fatal than Grumpy, the T-Rex.

Legacy

A thoughtful Tenzer understands why the series endures, even in the age of CGI. "People who love the show remember that time in their lives. That's the attraction of nostalgia. Seeing Land of the Lost again today is like reviewing a film reel of your life."

"We had believable characters and good stories," Lally told me. "That always makes for popularity. The nice thing too is that there is a new crop of children every three or four years. So you can show these episodes because they're not history dependent. They're not pinned down to a time. There are always new audiences."

"In the show, there were a variety of morality issues, and there was a variety of truth that came out in different ways," suggests Spencer Milligan. "In dealing with each other on an emotional level, we dealt with family issues. It was a much more simplistic show than some. Even though it was science fiction -- going back in time and living in that kind of circumstance -- we still had to deal with everyday problems."

Laurie continues to credit the Kroffts for the series' longevity. "We were part of an innovative approach to Saturday morning TV; we were taking kids' minds out for a walk."

"Let me say this. I knew Gene Roddenberry. He was a man of great passion...he was passionate about space and the potential of other worlds. When people like Gene Roddenberry or the Kroffts think in terms of big picture, they get outside of ego and into these wonderful philosophies. That's why projects like Land of the Lost work. That's why they become legendary."

A gracious Marty Krofft countered that any program's success results from collaboration; a synthesis of many talents. "We had some incredibly imaginative people help us do that show. If we took credit, we'd be lying. We had great writers, great music, the whole nine yards...."

September 6, 2024

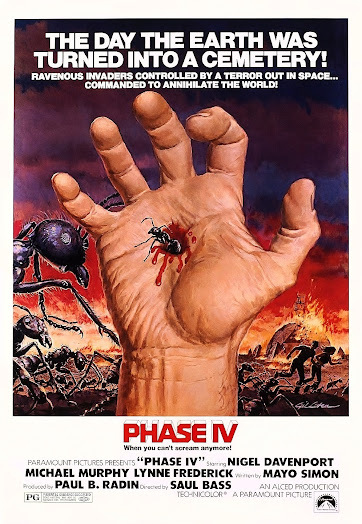

50 Years Ago: Phase IV (1974)

Saul Bass (1920 - 1996) was one of the cinema's greatest graphic designers, a revered film artist who contributed the memorable title sequences of such films as The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), North by Northwest (1959), Spartacus (1960), Psycho (1960), Good Fellas and others. Bass also storyboarded for Hitchcock the famous shower scene with Janet Leigh in the aforementioned Psycho.

Bass's only contribution as a director, however, is the little-seen but highly entrancing fifty-year old science fiction horror film of the early disco decade, Phase IV (1974).

In Phase IV, A strange phenomenon occurs in outer space, one that changes variables in "magnetic fields." The mystics on Earth predict earthquakes; others predict "the end of life as we know it."

But when the cosmic effect reaches our planet, the change it causes goes unnoticed, at least for a time. Because it affects only the smallest of us: the ants. Specifically, ordinary ants of different species soon begin communicating with one another, and "making decisions."

Linguist/computer scientist James Lesko (Michael Murphy) heads to a desert in Arizona to learn more. There ants begin to construct tall monoliths...a series of very advanced, human-proportioned towers. The ants have also mysteriously begun to attack livestock: burrowing inside animals and leaving a distinctive mark of three small circles. They've even begun crafting huge crop circles...perhaps paving the way for an alien invasion.

An obsessed, egomaniacal scientist named Hubbs (Nigel Davenport) also takes up residence in a small high-tech dome adjacent to the ant towers, in hopes of understanding what the ants are up to. When the ants go stealthy; refusing to show their hand, Hubbs decides on a pre-emptive strike to draw them out. He launches grenades at the ant towers and brings them all down in a destructive flurry, reducing them to rubble. By moonlight that very night, the ants retaliate: first by attacking a local farm, and then establishing a ring of reflective towers around Hubb's dome; towers that will burn the humans out after first rendering their computers inoperable.

Meanwhile, a farmer's beautiful daughter, Kendra Eldridge (Lynne Frederick) survives the ant strike on her family ranch and joins the scientists as they attempt to solve the riddle of these highly-advanced insects. Hubbs wants to launch a decapitation strike; to pinpoint the Queen Ant and kill her, thus nullifying the ant threat. "You must show them that man will not give in," he believes. By contrast, Murphy (with the help of his computers) learns the ant language and starts to transmit geometric shapes and mathematical figures to them, hoping that there can be some "rational accommodation of interests; some agreement" between species.

All throughout the film -- as the ants grow more intelligent...and remain one step ahead of the perplexed human scientists -- titles appear on-screen indicating different "phases" of this odd and increasingly apocalyptic crisis. The final phase -- Phase IV --arrives with a new dawn, a new sunrise, as the ants use Kendra to draw out Lesko. What occurs in the film's final sequence -- as Kendra and Lesko meet (and mate...) inside a sandy ant hill -- represents some weird sort of species apotheosis (for man and the ants...). This trippy climax renders Phase IV the 2001: A Space Odyssey of attacking-ant movies. It intimates that the ants -- experts in specialization and self-sacrifice -- have begun to teach humans the very same qualities. And that, with the ants help, humans are now evolving into...something else. The film's final line indicates a weird ambiguity. "We were being changed and made a part of their world," says Lesko.This description could easily portend a new beginning for humanity, one of true freedom and cooperation. Or it could represent slavery...under the domination of the ants (or aliens who have utilized the ants?)

Phase IV makes splendid and pervasive use of close-up natural photography of ants and other insects (conducted by Ken Middleham). There is no Hollywood fakery involved in these amazing, lengthy sequences: no models; no digital creations...just real ants going about their business with frightening dedication. There's an almost awe-inspiring (and again, totally real...) sequence in which one ant attempts to carry back to the Queen a piece of the pesticide that has killed his brethren. Exposure to this pesticide chunk is fatal to the ant, but he marches along, as far as he can. When he expires, another soldier ant arrives and continues the journey. When that ant dies, another ant arrives and continues the journey. This goes on and on - uninterrupted by human interaction or comment - until the last ant gets the chunk of poison to the queen, and she very quickly is able to create immunity to the weakened poison in future generations, as she lays eggs

Another scene of incredible visuals involves the ants lining up their dead after one of Hubbs' attacks.. They lay the corpses out in rows, belly (or thorax...) up...and then stand at a form of attention; as if honoring their dead at a funeral. It seems odd at first, but Bass determinedly grants the ants and their side as much screen time as the human stars and the effect is startling and interesting. One starts to wonder which species is altruistic and which is warlike; which species understands love and which species doesn't. Hubbs insists that the ants aren't individuals, but rather merely "individual cells." The ants do understand self-sacrifice -- to protect their queen -- because she is at the center of their lives. Yet Hubbs doesn't see that this urge to protect the queen is, in some form, an act of love. He can only see the ants as an enemy; as an inferior enemy, actually. In his smug blindness, he doesn't see how he is outmaneuvered. By balancing the ant storyline against the human one, Bass crafts a strange but powerful sense of equivalence.

Who are we -- in these circumstances -- to judge ourselves superiors? Who are we to -- as Hubbs suggests -- to teach the ants "limits?" To "educate them?" Indeed, Hubbs is hardly praise-worthy or a paragon of virtue. He treats even his fellow man with cold stoicism. "People die sometimes," he says at one point, without any expression of true feeling. What makes him the better creature?

Phase IV is an unsettling, spooky film. It's not just about a war between man and insect. Rather it depicts a war between the ideals of individuality and the community. Bass shows us the ant world on a scale we've never seen before, and even though these smart ants oppose us and our culture, you can't leave this film without some sense of admiration for them.

In the end, Hubbs would have done well to remember that old proverb: "Be thine enemy an ant, see in him an elephant."

September 4, 2024

Finalists!

Our new web series, Abnormal Fixation has now advanced to the level of FINALIST in the prestigious Oniros Film Awards in New York, in all six categories we were competing in:

Best Actress (Alicia Martin)

Best Actor (John Kenneth Muir)

Best Supporting Actor (Chris Martin)

Best Sound Design (Tony Mercer)

Best Screenplay (John Kenneth Muir)

Best Web Series!

My congratulations to the entire cast and crew, and my deepest thanks to the "big dreamers" at Oniros, for helping make our dreams come true.

We learn on Friday, September 6th if we make it to the level of award winner!

September 3, 2024

Abnormal Fixation has advanced to Semi-Finals in Oniros Film Awards!

Our little indie web series, Abnormal Fixation, premiering in October, has advanced to the semi-final category at the prestigious Oniros Film Awards in NY!

We are advancing in the following categories:

1. Best Screenplay (John Kenneth Muir)

2. Best Web Series (Abnormal Fixation; the Lulu Show LLC)

3. Best Actress (Alicia Martin)

4. Best Actor (John Kenneth Muir)

5. Best Supporting Actor (Chris Martin)

6. Best Sound Design (Tony Mercer)

Tomorrow, September 4th, finalists are announced, so cross your fingers for us! So excited and humbled for our cast, crew and show to be receiving all this incredible recognition in advance of its premiere.

August 31, 2024

Guest Post: A Quiet Place, Day One (2024)

The Fault In Our Star-ship Troopers

By Jonas Schwartz-Owen

Finally, the spend-your-last-day-on-Earth-to-the-fullest love story/alien bug mash-up for which audiences have been clamoring. A Quiet Place, Day One, a prequel to the hit John Krakowski films, hands the reins to Michael Sarnoski. While the action scenes seem like retread War of the Worlds, there are tiny magical moments that illustrate Sarnoski’s talents.

Sam (Oscar winner Lupita Nyong'o) is dying of cancer in a hospice center across the bay from Manhattan. She has lost hope and will, and only wants to relive a memory from her childhood with a slice of pizza in Harlem. She reluctantly agrees to join fellow patients to the city so she can indulge in this final slice. Vicious creatures who look like giant crickets with xenomorph mouths land on earth and quickly demolish civilization. Sam, her cat Frodo, and the hospice nurse (Alex Wolff) wind up hiding in a theater under attack. As she journeys up to Harlem for that pizza, she picks up a dazed, shellshocked Eric (Joseph Quinn), who tags along, as they escape monsters at every turn.

Sarnoski made the exhilarating Pig in 2021 starring Nicolas Cage in one of his best performances. Both films follow a simple genre plotline but find layers in the unlikely relationships. The invasion sequences have been done before and shot/edited better by other directors, but choosing a protagonist ready to die but invested in a trivial but momentous (to her) journey elevates the through-line. The marionette performance, the charming scene at the jazz bar, the rapport Sam has with both Eric and Reuben, the nurse, go beyond the one-dimensional relationships in many action films. Though Sarnoski leaves out the central Abbott family of the first two films, he ties Day One to the sequel by reintroducing Henri (Djimon Hounsou) in New York, before he escaped to the island where Emily Blunt’s character finds him later.

The script has a few quizzical short-hands. We’ve sadly seen governments in chaos before in the real world, and information does not flow quickly. Yet, in the movie, the government manages to decipher and disseminate that the aliens can’t swim, and the fact that noise draws them to attack, within an hour. That’s a lot of details to get to the panicked public under attack and makes you wonder if the Director of Defense watched the first two films as a primer when the monsters begin raining down in the major cities.

Nyong'o plays all of the emotional beats so you warm to her even though she has essentially given up on fighting to live. The character starts as despondent and though her impending death still doesn’t worry her, she’s more at peace and heroic than miserable. Quinn, who won over Stranger Things audiences as the misunderstood rocker, Eddie, has an endearing persona and builds great chemistry. Their scene in the Harlem Jazz Club is celebratory.

A Quiet Place, Day One, may have not proven its necessity to exist -- the information it adds to the saga is meager -- yet, Michael Sarnoski is a special director, who’s reminiscent of the RKO ‘40s legendary producer Val Lewton. It’s never the title nor the plot line that invests the audience in his films, but his reflection of the human condition in even the most insane circumstances. It would have been more interesting to see what he could have done if all the extraneous action scenes were stripped away.

August 29, 2024

Abnormal Fixation: Two new Quarter Finalists at Oniros Film Awards!

I am thrilled today to announce that the prestigious Oniros Film Awards in New York has named our upcoming web series Abnormal Fixation (to air the October!) a quarter finalist in two additional categories beyond best web series, the award we are also up for.

Alicia W. Martin, my co-author on The Subway Game (2024) and the lead of Abnormal Fixation, is a quarter finalist for Best Actress. Alicia is amazing -- simultaneously real AND funny -- in the role of Season Winters, and I can't wait for you to see her in the show. Alicia brings charisma, passion and energy to the role of a long-suffering spouse and forensic biologist with some...quirky tastes. Congratulations, Alicia!

Oniros Film Awards also honored us with a quarter finalist designation for sound design, and that's all Tony Mercer. Tony its an incredible talent, and world builder, the sound engineer, mixer, editor responsible for the wondrous multiverse of Enter The House Between (2023). His accomplished sound design for Abnormal Fixation lifts all boats, and showcases our story and cast to the nth degree. Congrats, Tony!

We'll find out next week if we move up to semi-finalist designation in the categories of best web series, best actress, and best sound design, and I'll keep you all up to date on the results!

August 26, 2024

30 Years Ago: Natural Born Killers (1994)

Following two surreal hours of ultra-violent imagery and deep social criticism, Oliver Stone's controversial 1990s masterpiece,

Natural Born Killers

concludes with fact.

Following two surreal hours of ultra-violent imagery and deep social criticism, Oliver Stone's controversial 1990s masterpiece,

Natural Born Killers

concludes with fact.

Specifically, the film ends with real-life footage of the Waco/David Koresh stand-off, disgraced ice skater Tonya Harding taking a tumble, Lorena Bobbitt on the witness stand (on trial for cutting off her husband's penis), the murderous Menendez Brothers, murder suspect O.J. Simpson, and even Rodney King asking (famously): "can't we all just get along?"

This montage is an exclamation point; a sharp punctuation capping off a fiercely presented argument. It states: "welcome to the tabloid-TV culture of America in the 1990s; where crime pays, and pays well." Commit a notorious murder and you are...a superstar.

Who's that on the phone? The Jenny Jones Show is calling...

Accordingly, Natural Born Killers was advertised on theatrical release as a "bold new film that takes a look at a country seduced by fame, obsessed by crime, and consumed by the media."

And yes, that indeed represents truth in advertising.

Natural Born Killers -- a sensational bombardment of incendiary sound and imagery -- burns through its expansive running time with a blazing indictment of the mainstream media.

The charge? Lowering the national discourse. Finally, director Stone makes his explicit closing argument with real-life archival footage.

Natural Born Killer's closing montage declares, essentially: You think we're exaggerating?

You think we're kidding? Well, lookie here: this is who we are (to appropriate Millennium's confrontational [1996-1999] tag-line). The documentary-style final montage pointedly connects the misadventures of fictional mass-murderers Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis) to the real-life celebrities who found fame and fortune the same way. It tells us that even though Natural Born Killers qualifies as satire, it is hardly exaggerated in terms of narrative content (though style and presentation are different arguments entirely.)

This closing documentary montage also represents Oliver Stone's inoculation from critics who complained that he was coarsening the dialogue himself. On the contrary, Natural Born Killers represents cinematic commentary at its finest because it draws together so many disparate cultural elements and synthesizes them into a lucid, pointed critique of the times. After making its case in fictional and artistic terms, it graduates to the terrain of the real and we see there is little gap between what Stone has imagined and was happening every day on our televisions.

Sitcom America: Or I Love Mallory

Early in

Natural Born Killers

, the film re-constructs, in flashback, the first, fateful meeting of Mickey and Mallory.

Early in

Natural Born Killers

, the film re-constructs, in flashback, the first, fateful meeting of Mickey and Mallory. This sequence is presented as a black-and-white TV sitcom from the 1950s. Something along the lines of Leave it to Beaver (1957-1962) , or, of course, I Love Lucy (1951-1957).

This "sitcom" of Mallory's family life in Natural Born Killers charts the colossal gulf between the imagery sold to America regarding family life, and the truth, for many Americans, of such family life in the 1990s.

Specifically, a greasy, monstrous Rodney Dangerfield portrays Mallory's Dad in this sequence and, well, let's just establish he is hardly Robert Young in Father Knows Best (1954-1960). On the contrary, he is verbally and physically abusive to his wife (Edie McClurg) and his children. He gropes his own daughter and even sexually abuses her.

Again, this is a far cry from the perfect domestic bliss of The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet (1952-1956).

When one of the first national surveys regarding childhood sexual abuse was conducted in 1989, researchers discovered that such abuse was prevalent in a whopping 27% of respondents. To parse that figure, on the cusp of the 1990s more than one-in-four American women reported being sexually abused by family members during their formative years. That's not just a shameful statistic, it's an epidemic. But the media wasn't going to connect the dots for us. It was too busy feeding us reinforcing images about the American family (in empty-headed sitcoms), and, at the opposite pole, entertaining us with the bread and circuses of talk shows.

Natural Born Killers threads together these two disparate worlds. One commercial image was patently idealized and false (dangerously so), and the other encouraged our worst rubber-necking instincts. Was it any wonder our culture had become so schizophrenic? Self-righteously moral on one hand, and voyeuristic on the other?

In Natural Born Killers, the form of the sitcom or "situation comedy" reveals Mallory's life as she imagined it should be (replete with an oppressive laugh-track eradicating any scary sense of ambiguity). But the content of that domestic drama reveals the grim truth of it. "She has a sad sickness," Mickey notes of Mallory at one point. She "wanders in a world of ghosts." Those ghosts are black-and-white ones transmitted by a flickering cathode ray tube; images of perfect sitcom personalities who don't exist in real life. Mallory is haunted by the media's image of family life, unaware that it can never be.

You're Buying and Selling Fear: Mass Media as The Devil

In Natural Born Killers, Robert Downey Jr. plays Wayne Gale, the arrogant host of a lurid "true crime" TV series called

American Maniacs

.

In Natural Born Killers, Robert Downey Jr. plays Wayne Gale, the arrogant host of a lurid "true crime" TV series called

American Maniacs

. Gale is not, however, concerned with truth or objectivity, merely with high ratings, which will bring him wealth and personal fame. Gale is so smug that he looks upon his subjects as "apes" and notes he is the "God" of his own world.

Mickey and Mallory's cross-country killing spree is thus an opportunity for Wayne to grand-stand, to look powerful in front of his audience. He schedules a live interview with the incarcerated Mickey for Superbowl Sunday. And there, the vainglorious Wayne shall show off to the high heavens. He will look heroic by verbally jousting with the "monster," Mickey.

When a riot begins in Mickey's prison, however, Wayne blurs the lines. He goes from reporting on the crimes to participating in them. He picks up a gun and actually starts shooting police officers to keep the broadcast going, to keep the story alive.

The message is clear here, isn't it? The media is complicit in the crime sprees it reports with such verve.

Occasionally in Natural Born Killers, Oliver Stone jump cuts -- in almost subliminal fashion -- to expressionistic visuals depicting Wayne Gale as the Devil. Actually, as a blood-soaked Devil. Since this character symbolizes the media in the film, Stone is making a comparison of "evils," and finding the mainstream media amongst the worst. Natural Born Killers reveals clearly how criminals and the media work hand-in-hand. The media transforms criminals into celebrities, and the criminals in turn, hand the media high ratings. It's a win-win arrangement in what Stone calls a "fast food culture."

In keeping with this theme, there's a great montage midway through the film that features "people on the street" in London, Tokyo, Paris and America professing their undying love of killers Mickey and Mallory.

The spree-murderers also make the covers of People, Esquire, Newsweek, The New York Post and other periodicals.

That which is famous must be good, right? Stone even cuts to Brian De Palma's Scarface at one point, and, as viewers, we are asked to ponder an important question. Why do we, as Americans, worship our gangsters? Why do we admire killers?

Like Remy Belvaux's brilliant satire, Man Bites Dog (1992), Stone's Natural Born Killers suggests that, in the unending quest for a greater audience share, the media can't help but participate and encourage the violent stories it reports on and profits from. The irony is that Mickey and Mallory understand this "evil," and put an end to Wayne Gale: they kill him on camera, effectively killing the media's role in their particular story. To some people, this makes these bad guys -- on some weird level -- admirable.

Many right wing critics complained vociferously about Natural Born Killers. It indeed seems to present unrepentant murderers as the "heroes" of the piece. My response to this argument is two-pronged.

First, Natural Born Killers is a surreal, avant-garde expression of Mickey and Mallory's story, and to them, they certainly are the heroes of their adventure.

And secondly, Stone boasts no illusions about his protagonists. In fact, he continually associates the two killers with the symbol of the rattlesnake.

A rattlesnake is not, in a strict sense, evil. A rattlesnake is, however, a dangerous killer. And, in the lingo of the film (and Mickey himself), Mickey and Mallory are "natural" born killers, meaning that they were made this way...like the rattlesnake. I take this to mean they were socialized to become society's rattlesnakes. They are not evil, per se, they are merely living according to their nature. And even though they are murderous, at least they love each other.This is not a glorification of violence or brutality, it's a notation, I submit, about honesty. Mickey and Mallory are honest about themselves. They are the only people in the film who can make this particular claim. They are exactly what they appear to be: Natural Born Killers.

Mallory's Dad is not a loving force of paternal wisdom as the sitcom form suggests he should be...he's an exploitative sexual abuser. Wayne Gale is not a tribune of the people and honest broker of the facts, he's a sideshow barker and rubber-necker seeking personal fame and glory. Even Tommy Lee Jones' warden and Tom Sizemore's police detective, Scagnetti, are not symbols of legitimate law enforcement, but rather sick sadists looking to get their piece of the pie.In a world of such personalities, Mickey and Mallory are indeed a lesser evil because they know what they are and don't pretend to be something else. At the very least, they aren't "buying and selling" an artificial image.

It's no coincidence that Mallory is depicted, at one point in the film, reading Sylvia Plath's 1963 novel, The Bell Jar. That story was set in a complacent, slick modern society of tremendous hypocrisy. The main character, Esther, was a tabloid writer aware of the lurid details of the jet-set. In real life, Plath chose suicide rather than continue existence in such a culture. In Natural Born Killers , Mickey and Mallory choose homicide as a solution, but in both cases, the act seems a protest against a garish, excessive world built on tabloid pillars.

Oliver Stone's film stops very far short of endorsing Mickey and Mallory as role models or model citizens, however. During one powerful scene, a window in a hotel becomes a TV screen of sorts. Behind Mickey and Mallory we see images of Stalin and Hitler prominently displayed. Worship these people at your own risk, the movie seems to say. It's a slippery slope indeed from Mickey and Mallory to O.J. Simpson to The Menendez Brothers to Hitler or Stalin. Why? The celebrity culture thrives on ratings, not on inherent worth or morality. We should not mistake fame or infamy for virtue, and that's a key message of Stone's movie. (And, yes this explains Donald Trump, doesn't it?)It's a well-known fact that Columbine Killers Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris used the term "NBK" (Natural Born Killers) as code for their own horrific killing spree. But these young killers certainly took away the wrong lesson from Stone's film.

They imagined being famous, whereas fame is something that Mickey and Mallory never covet or desire in the film. Stone's film criticized such fame, and specifically, we have that ending montage to confirm that Natural Born Killers is intended, indeed, as social criticism.

Mickey and Mallory are rattlesnakes in Natural Born Killers , and they almost die while crossing a field of authentic rattlesnakes. That image, perhaps, is the film's most resonant one. It's not just a regurgitation of the old live-by-the-sword/die-by-the-sword truism, but a comment on the very nature of our culture and corporate media.

Natural Born Killers? Mickey and Mallory are practically babes in the woods compared to the cynicism of Wayne Gale, Jack Scagnetti and the other vultures they encounter in this film.

August 25, 2024

60 Years Ago: Godzilla vs. The Thing (1964)

Godzilla movies can often be quite blunt in presentation, so -- in honor of that trait -- allow me to be blunt about Godzilla vs. The Thing (1964).

It is, basically, a superior, artistically-coherent version of King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962).

This movie dramatizes a very similar tale, but Godzilla vs. The Thing ties all the familiar elements together into a caustic and effective critique of Big Business.

Accordingly, this film feels far more direct and meaningful than its predecessor did. In fact, I would agree with critics who state Godzilla vs. The Thing is one of the all-time best Showa Godzilla films.

In particular, it is noteworthy how Godzilla vs. The Thing forges a link between irresponsible Big Business and environmental and manmade catastrophes. Even Godzilla himself is contextualized in light of this nexus.

In man’s blazing desire to profit from things that aren’t his to profit from, says the film, he risks total apocalypse, even if that apocalypse is unintentional.

But Godzilla vs. The Thing doesn’t desire to be a polemic, either, and also comments meaningfully on man’s connection not just with nature, but with his fellow man.

The great Mothra -- who has seen her island devastated by atom bombs -- could refuse to help civilized Japan in its hour of desperate need. But, as the film states, “we must learn to help one another,” or we’ll all go down, if not to rampaging Kaiju then to some other dire threat.

Agree or disagree with its premise about reckless capitalism, Godzilla vs. The Thing really works splendidly, and the battle scenes are fantastic too, featuring more cut-ins and extreme close-shots so the fighting monsters seem even more vicious than before.

“Money, that’s all they’re interested in….” Following a dangerous typhoon, a reporter, Ichiro (Akira Takarada), and his new photographer, Junko (Yuriko Hoshi) survey the damage to the shore-line. They uncover a giant reptile scale, but that discovery pales in comparison to another.A giant, colorful egg has been seen in the shallow waters of the coast. This colossal egg is brought ashore by the poor locals, and studied by scientists, including Professor Miura (Hiroshi Koizumi) until a businessman named Mr. Kumayama (Yoshifumi Tojima) brazenly explains that the egg is his property. He has just purchased it from the desperate locals, who have endured the typhoon damage. He plans to sell it to the head of Happy Enterprises, with the express purpose of creating an amusement park attraction based on it. Soon work is under-way to incubate the egg in a large structure…Before long, the Shobijin -- two tiny fairy women -- appear in Japan, and ask the businessmen for the return of the egg to its home on Infant Island.,The egg belongs to their deity, a giant old creature called Mothra. Their pleas are ridiculed and ignored, however and the small women face capture themselves. They escape from custody and return to Infant Island.Meaenwhile, Godzilla rears his head in Japan again, this time near the beach where he washed ashore (and lost his scale…) in the hurricane. Godzilla promptly begins to cause great damage to Japanese industry and property, prompting Ichiro and Junko to visit Infant Island and beg Mothra’s help to defeat him.On the island, Mothra’s help is solicited, even though the island has been ravaged by atomic testing, and civilized man refused to return the giant monster’s egg. Still, Mothra agrees to help…but the monster is aged, and may not be able to defeat Godzilla.When Mothra dies in a fierce battle with the giant radioactive lizard, her egg finally hatches, and two Mothra grubs continue the fight, for all mankind.

“I’m sure they hate us for what happened here.”

If the angle about a pharmaceutical company and its CEO was played largely for laughs in King Kong vs. Godzilla, a similar plot-line gets more serious treatment in Godzilla vs. The Thing . Here, a company takes possession of an egg it clearly didn’t hatch, and offers to let scientists study it…for a price.

The “entrepreneurs” that turn this egg into a commodity hope to mint a fortune by making it the center of a tourist attraction. In short, they seek to exploit that which is not theirs. An egg is a symbol for nature, and for life, but these men see it as a golden egg, a path to personal wealth.

Then, when the fairies -- speaking on Mothra’s behalf -- ask for the return of the egg, the company people all but laugh at them. The egg is the company’s asset now, and they have extended themselves with some expense to build an incubator, and so forth.

There’s no way the company is giving it back.

Uniquely, the company’s representatives see the egg exclusively as property. They purchase it from a previous (illegitimate…) owner, the locals whose land it came to rest on. But now, because payment was made, it is a resource that belongs to the company for reasons of exploitation.

In contrast, the fairies make an argument based not on property, but on the common good. They are afraid that the egg could hatch, and inadvertently cause tremendous destruction. The fairies, in other words, are looking out for all mankind, while the company just cares about its own profits.

The fear that a hatched egg could inadvertently cause tremendous damage is significant in Godzilla vs. The Thing and we see that fear realized visually with Godzilla. He begins a reign of destruction in Japan, but notice that in this case, his destruction doesn’t seem at all intentional.

For example, his tail gets caught in a tower, and the tower falls down on him.

Moments later, Godzilla actually slips on a stretch of land. He loses his balance, and falls into another building. Then, trying to stand-up and re-balance himself, he further damages the building.

This is not the behavior of angry animal pulping a city. This is a natural force doing what natural forces always do: inadvertently causing great damage in man’s world. There is not malicious intent, but damage is nonetheless caused.

The commentary about big business in Godzilla vs. The Thing also extends to journalism.

Journalism is supposed to be a beacon of hope, exposing corruption and danger and keeping the public informed in a timely fashion. But as one character notes “a newspaper has a limited capacity to reach people. It can’t enforce the law.”

By implication, the government – in bed with big business – should be the one enforcing the law, but it isn’t doing so.

Again, Godzilla vs. The Thing forges its critique of laissez-faire capitalist practices. The government and military in vain try to stop Godzilla’s reign of terror, when a route of diplomacy -- with the fairies – has been neglected.

The general idea applies to Mothra’s island, as well.

Look what the countries of the so-called First World have done here, with their fearsome, high-tech military-industrial complex. Such forces have destroyed a once-beautiful island, leaving it an environmental wreck. Only one small area is still green, and the rest of the island is barren, littered with skeletons.

The land -- representing nature itself -- was used as man’s property (much like the egg is treated as property…), by people unconcerned with the common good, focused instead on ideological or material profit.

But Godzilla vs. The Thing isn’t cynical or pessimistic about such matters, which is one reason why I love it so much. Instead, the film is actually hopeful, and shows that two wrongs don’t make a right.

Mothra and her people were treated rudely by the new owners of the Egg, and their needs and desires were never taken into account. It would be easy to treat the people of imperiled Japan the same way now.

The people of the island could have reciprocated cruelty with cruelty. They could have stuck to their “we will not help” line, when assistance was requested.

Instead, the fairies see how bad judgment should not be repaid with bad judgment. A line of dialogue in the film notes that “as humans, we are responsible for each other,” and that’s the film’s positive message.

If we can help each other in a time of crisis, we must do so. This is true even in times when there is nothing for us to “gain” or “earn.” That’s the behavior Mothra models. The giant creature is weak and infirm, and has no “vested” interest in fighting Godzilla. But Mothra goes into battle for the common good, putting selfish concerns aside.

It’s true that Godzilla vs. The Thing moves along some familiar story lines and plot points. As was the case in King Kong vs. Godzilla , we here visit the native island and meet a culture that worships another monster. In both cases, that “other” monster is recruited to battle a rampaging Godzilla.

And also as in King Kong vs. Godzilla , Godzilla apparently goes down in the last round, and the victor (Kong or the Mothra grubs…) begins the long trek back to an island home.

In this case, the two closing shots are practically identical.