Rod Dreher's Blog, page 80

February 26, 2021

Woke March Through The Institutions

A common complaint I get from people on the Left when I talk about Live Not By Lies is that I overstate the threat from the Woke. How can you say that we are in danger of soft totalitarianism when Donald Trump is the president and the Republicans hold the Senate? Or, more recently, You have some nerve, saying the threat is from the Left, when on January 6 a pro-Trump mob invaded the Capitol!”

Well, look, it would be absurd to claim that the Right has no power. Even today, with the White House and the Congress in Democratic hands, Republicans remain powerful. But these objections from the Left are superficial, because they focus on superficial manifestations of power. As appalling as the January 6 attack was, it represented only a tiny fraction of Americans on the Right, and it had zero chance of overthrowing the government of the United States. If you think it did, then you are telling yourself a lie.

Second, Trump certainly was a powerful man in the presidency, but his power was sharply mitigated by the fact that he did not know what to do with it. All of the totalitarian trends I document in Live Not By Lies accelerated under Trump. He made a few gestures towards stopping them — his late-term ban on Critical Race training in federal agencies, for example — but these were minor, and easily overturned once Trump was gone. Trump’s ardent supporters are just as deluded about his power as his ardent critics. His opposition to wokeness was mostly performative. Again, if he had been interested in how to use power, we might have seen something different, but he wasn’t, and we didn’t.

Besides, to be fair to him, a president is not an absolute monarch. He can’t order private industry to do what he wants them to do. And the Republican Party has no stomach for culture war. In the first two years of Trump’s presidency, the GOP held both houses of Congress, and the presidency. It could have passed legislation that Trump, however disengaged, would have signed, legislation that would have struck meaningful blows against the march of wokeness. It did not; the Republican Party focused on a tax cut for business.

The real power in this country, and in most countries, resides in institutions, and in the networks of elites that run them. The sociologist James Davison Hunter, in his 2010 book To Change The World, addressed his fellow Evangelicals, and told them that they are mistaken to believe that convincing the masses is the way to change the world. In most instances, you have to convert elites and their networks; change follows that. In other words, elites and their networks are the ones who lead the masses.

You maybe read my bit yesterday about the new Gallup numbers showing a skyrocketing number of Gen Z Americans identifying as LGBT. Most of that, it turns out, is young women calling themselves bisexual. Even so, this is not a natural occurrence. This is the result of two decades of media propaganda about sexual orientation and gender identity. Elites in the media and the academy moved the Overton window to where it became possible for the masses to think of themselves as sexually fluid. This aspect of the Sexual Revolution didn’t happen on its own.

I remember exactly where I was, and what I was doing, when I knew that gay marriage was going to win. It was the spring of 2003, and I was unpacking boxes in the living room of our new house on Sudbury Street in Dallas, from the move from New York. We had the TV on, watching Prime Time Live as we worked. Diane Sawyer dedicated the entire episode to telling the story of a gay male couple that had worked with a surrogate to have a baby. By the end of the show, everything had gone badly, then men wanted out of the deal with the surrogate, who was left mothering a fatherless child. Everything about this was grotesque and cruel (to the baby) — but Diane reported it in a lighthearted, “hey, that’s life!” way, as if to say you have to expect things like this to happen on the road to equality.

I turned to my wife after the show was over and told her that us conservatives were going to lose the gay marriage battle, because we can’t compete with that kind of messaging. On the face of it, what happened there was terrible. At least a fair-minded examination of it would have brought some criticism to what those three adults had done. But none of that was there. It was all advocacy. This is how broadcast and print media have covered gay issues for at least 25 years, and it is how they have covered trans issues for almost as long. The greatest allies the LGBT movement have had has been the media, because it is the media who have framed the issue — that is, determined the terms in which the masses think about it.

Anyway, the black Columbia University linguist John McWhorter, who is one of the bravest men in America, says in his new Substack newsletter that the belief on the Left that the Right is all-powerful is a fallacy, precisely because of the institutional nature of power. Excerpts:

Extremists from the right are more of a problem? It’s on.

1.

First let’s try roughly summer 2020. Remember the idea from the hard left that it was alarmist to think there was a woke takeover afoot?

Please know – I don’t mean “woke” as in “good lefty.” I mean “woke” as in “woke” in a way that makes you feel like it’s okay to be mean. As in what I call The Elect. And The Elect, interestingly, tend to resist the idea that they are making inroads. This is because they see it as a defining trait that they are Speaking Truth to Power.

As such, they will always have a hard time allowing that they actually have any Power, which is why it is wrong to think they level their brickbats out of a desire for power – they definitionally will never admit that they have any, which makes them this much more challenging to exist among.

Anyway, this idea that The Elect have no real power is – despite that they will object — now officially obsolete.

It’s been deep-sixed by 1) basic intuition from anyone who takes a look at the news every day and 2) things like, if I may, my Atlantic piece on academics writing me from all corners sick to death at watching religious “antiracist” ideology (as opposed to pragmatic, fact-based antiracist ideology rooted in grass-roots activist reality) take over their institutions.

Yep, that was based on only a hundred-odd “anecdotes” – but just three “anecdotes” about white cops killing black people (or landlords preying on black tenants, or doctors thinking of black people as more tolerant of pain) are accepted as portraits of America writ large. We must be consistent.

Especially since my Substack comrade Bari Weiss reports almost daily contacts from people desperate about the same thing, as does my sparring partner on the Glenn Show. Then also organizations such as FIRE, devoted to fostering genuine free speech in academia, as well as Heterodox Academy and FAIR (stay tuned) hear from similar legions of people with the same burdens (and you don’t even need to ask whether I am connected to all of those organizations).

More:

2.

So – there is a house on top of the idea that someone like me is just whining. But now there’s a new distraction – that the racist, roiling alt-right who just invaded the US Capitol building and lurk menacingly here and there, often even with guns, threatening to take “America” back by force, are more of a problem.

So, I wring my hands about somebody holding a copy of How to Be an Antiracist close to his chest while some asshole storms the Capitol holding a Confederate flag.

Okay. Violence is scary. Gruesome. And I am unaware of anyone with a copy of White Fragility in their pocket storming into some government building with a gun asking for antiracist justice.

But the question is this.

The optics of that Capitol takeover were hideous. And we can know that people of those sentiments are gabbing incessantly in repulsive manner 24/7 on line.

Yet – what institutions are such people infecting?

Really. I will put it again.

What institutions are people like this taking over? Yes, they have websites. Yes, they summon one another to travel to Washington and make a big, vicious noise. Which then ended, with most of the perpetrators being arrested.

Which institutions are those boobs taking over? Which persons have seen them coming and yielded, such that now we say that an institution that once was fostering the Good is now marching to the tune of right-wing idiots?

What’s different now because of how they wanted things to go?

Because if you pause to answer that, you need to consider that The Elect are transforming institutions.

And:

I ask: is the loony right having the same effect on institutions as what we might, intemperately, term the loony hard left? Note, to the extent the that latter enjoy victories – and note that they do – they confirm that they are winning over the loony right. Because the loony right changes nothing; they merely alarm.

Read it all. I subscribe, but I don’t know if it’s behind a paywall. You should subscribe if you don’t.

In just about any mainstream institution you can think of, if you held woke beliefs, and weren’t shy about advertising that, not only would it not hurt your job application, but it would likely help it. If you held even mainstream conservative beliefs — not alt-right ones, but mainstream ones, such as being one of the 70+ million Americans who voted for Trump last fall — you had better know that you should make sure that is scrubbed from your online profile before you apply for a job at a university, a media outlet, or a corporation.

As McWhorter avers, the Left has a powerful need to see itself as always the victim, always the underdog. Twenty years ago, when people like me, conservatives who actually worked in mainstream media newsrooms, would say that the media was biased powerfully to the Left, you could always find a leftist who didn’t know jack to say, “Well, maybe, but media companies are run by rich people, who are conservative.” OK, I’ll give you Rupert Murdoch, but who else? Besides, on the neuralgic culture war points, the rich today are solidly on the side of the Woke.

Yet, the myth persists. Here, Yale’s Nicholas Christakis responds sarcastically to a leftist history professor at UMass who, in his thread, argued that Smith College is not run by the Left, because universities are really run by trustees, who, he says, are always center-right:

The claim made by Leftists that they are always and everywhere speaking for the powerless, against power, is necessary to their self-understanding, and key to the woke justifying their belief that, in McWhorter’s words, “it’s okay to be mean.” It’s why my woke ex-friend ended our friendship of 40 years this week, over my letter to the editor praising one of our US senators from Louisiana for voting to impeach Trump, but in so doing I acknowledged that Trump had done some good things. She felt justified in doing so because anyone who does not hate Trump with perfect purity is too evil to associate with.

This is what we face. There has, so far, been no meaningful political opposition to it. By “meaningful,” I mean politicians who are willing and capable of doing something about it. Don’t insult me by claiming Trump was that politician. Judge him by the results. If we on the Right put our trust in a champion shitposter, as opposed to political leaders who know how to get things done, we will keep getting our heads handed to us. And if we keep thinking that the problem is essentially political, as opposed to cultural and economic, we will make no progress. We will elect ineffective performers like Trump, while the doers on the Left continue to march through institutions and change them — and by changing institutions and networks, change America.

The post Woke March Through The Institutions appeared first on The American Conservative.

February 25, 2021

NYU’s ‘Disruption’ Commissars

A source inside New York University has leaked to me a shocking document titled “NYU Faculty Cluster Hiring Initiative Roadmap.” I have copied and pasted the original below; I have only left off names of faculty on the “Cluster Review Committee,” because I don’t want them to be subjected to doxxing or online harassment. If any journalists want to write about this story and would like the list of names, e-mail me at rod — at — amconmag — dot — com, and I’ll sent it to you.

Why is the document shocking? The Faculty Cluster Initiative is a new program meant to increase diversity faculty hiring. According to the document, non-white (“historically underrepresented”) students represent 41 percent of NYU’s student body, but only 20 percent of the faculty are non-white. Though there may be non-racist reasons for this, NYU doesn’t want to hear them. The racial discrepancy is unacceptable to NYU. The Faculty Cluster Initiative is meant to “disrupt” faculty recruitment and hiring procedures.

So what does it do? Once you cut through the woke Human Resources jargon (“vibrant,” “inclusive,” “holistically,” “positively impact,” etc.), it says this, according to my source:

1. Traditional hiring (the department, the people with expertise in the field, do the hiring) is a roadblock to diversity, and must be “disrupted.”2. Groups with “similar research interests” (like critical race theory and intersectionality) can now form “clusters” that can do an end-run around traditional hiring and just put someone into a department.This is how the woke are going to finally conquer STEM. Instead of, say, physicists, the departments will increasingly be occupied by people who write papers like “Quantum Mechanics: A Force for White Domination.”UPDATE: My source e-mailed after reading this to say:

No, “historically underrepresented” *excludes Asians, especially Asian males, because they are “historically overrepresented”! In fact, no one is going to be hit as hard by this initiative as potential Asian hires.

Below is the full document, minus the names of the Cluster Review Committee members:

The post NYU’s ‘Disruption’ Commissars appeared first on The American Conservative.

Rand Paul Blasts Levine’s Trans Radicalism

Please watch this stunning exchange between Sen. Rand Paul and Dr. Rachel Levine, the transgendered woman the Biden administration has nominated to be an assistant secretary of the Department of Health And Human Resources:

If you don’t have five minutes for that, click here, at the 1:31 mark, when Sen. Paul asks Dr. Levine if Levine believes that minors are capable of making rational decisions to undertake surgical and hormonal revisions to their bodies. Watch Levine’s non-answer.

Sen. Paul then repeats the question, asking specifically if Levine supports the government stepping in to overrule parents, and compel administering puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and/or amputation of breasts and the penis in minors.

Dr. Levine, the Biden administration’s nominee as an assistant department secretary, will not answer.

Sen. Paul’s pointing out that Dr. Levine advocates “acceleration” of hormone protocols in “street kids” comes from this 2017 speech Levine gave at Franklin & Marshall College, in which the physician said poor kids living on the street deserve to have the hormones they want, when they want them. Go to the 28-minute mark to hear it yourself.

People, this is how serious it is. This is how insane the Democratic Party and the medical community are. Rachel Levine is the kind of tyrant they want to rule over us. Here is how the liberal site Vox described the Paul-Levine exchange:

Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), meanwhile, used his time to promote transphobic misinformation.

In a moment in which the pandemic is exposing severe health challenges, especially for America’s most marginalized, Paul’s line of questioning was particularly egregious.

I can hear the progressive shrieking now: People will DIE because Rand Paul asked Dr. Levine a perfectly normal question! More Vox:

Paul was eventually cut off by health, education, and labor committee Chair Patty Murray (D-WA). She and other Democrats praised Levine for her professionalism in handling Paul’s transphobic remarks, and spoke to the greater problem Paul’s rhetoric presented.

“It is really critical to me that our nominees be treated with respect and that our questions focus on their qualifications and the work ahead of us, rather than on ideological and harmful misrepresentations like those we heard from Sen. Paul earlier,” Murray said.

Astonishing! Sen. Paul is asking the questions a lot of Americans would like to know about the policies the Democrats and their appointees will be advocating — policies that are going to result in children suffering penile amputations, irreversible breast amputations, fertility destruction, and other harmful outcomes. But even Democratic politicians say asking questions is bigoted.

Seriously, those questions Sen. Paul put to Dr. Levine are perfectly valid. The fact that the physician refused to answer them, and the Democratic committee chair chastised Sen. Paul as a bigot for posing them, is incredibly alarming. Why don’t they want people to know what they really believe?

The post Rand Paul Blasts Levine’s Trans Radicalism appeared first on The American Conservative.

No Escaping The Eyes Of God

If you haven’t seen my post from last night, Smith College Hates The Working Class, please do read it. It’s based on a long piece in the NYT about the atmosphere at the elite liberal arts college, the one that led to Jodi Shaw’s threatened lawsuit. It told me things I did not know about the situation there. I knew that there had been a controversy on campus a couple of years ago, when a janitor called campus police on a black student he saw in a place where she wasn’t supposed to be. The campus cop recognized Kanoute, the student, as a student, and apologized for bothering her. Kanoute recorded this interaction, which the Times described as a “polite” exchange. Later, Kanoute started a social media campaign painting herself, a student at this $78,000 per year college, as a victim of racism. Predictably, this caused Smith to engage in a spasm of “antiracist” activism, including from the administration.

What I didn’t know until I read the Times piece is that an independent investigation of the incident found that the janitor and the cop had done nothing wrong. The janitor, an older man with poor eyesight, had done exactly what Smith policy required him to do: if you saw someone you didn’t know in a place they weren’t supposed to be, you’re supposed to call the campus cops. Well, as the NYT piece details, this whole controversy ended up punishing both the janitor and a cafeteria worker that Kanoute wrongly believed alerted the police. Both are working-class people with health problems, making significantly less than a single year’s room and board at Smith. They were berated by students with accusations of racism. It was horrible what was done to them. The story makes it clear that the liberal elites who study at Smith, and who run Smith, are perfectly willing to run roughshod over working people, in an effort to achieve their idea of social justice. As one editor put it:

I liked this observation by the black writer Thomas Chatterton Williams:

The problem is not just one of young, individual non-whites, but of all young people indoctrinated by our academic class. This morning I was e-mailing with some people about Dante, and mentioned a lecture I gave a few years back, in which, during the Q&A period, a young woman asked me earnestly if I really thought that we have anything to learn from a white European man who was the product of an oppressive society. I was nonplussed by this, because it was at a Christian event in Wichita. A professor approached me after the talk and said that this is how young people are all taught these days.

That young woman is a victim of an ideological pedagogy that trained her to regard something as complex as the poetry of Dante Alighieri as nothing more than the product of a privileged white male elitist. Never mind that Dante wrote from the position of someone who had been exiled by the ruling elites of Florence, and lost everything he had. Here is a young woman in 21st century America, the product of the richest and freest society that has ever existed, and such is her intellectual poverty that she can only understand the work of one of the greatest poets who ever lived in crude, culturally Marxist categories. The people who maimed her mind that way ought to be horsewhipped.

TCW’s remark in that tweet highlights a serious problem I see with wokeness, particularly Critical Race Theory, infiltrating and conquering Christian institutions. A central aspect of Christian spirituality is learning that no one is righteous, that everyone has sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. Being victimized does not give you the right, as a Christian, to hate your victimizers. This is why Dr. Silvester Krcmery, a young Christian physician who was imprisoned and tortured by the Communists in his native Czechoslovakia, had to work hard in his prayer life not to hate his captors and torturers. His Christian faith taught him that to come to hate them means victory for the Evil One. Certainly no ordinary person could have blamed him for despising those who treated him like this, but Dr. Krcmery knew, as all Christians must, that the follower of Christ is commanded by Our Lord to love those who hate him.

It’s a hard commandment to follow. I found myself last night praying for someone who despises me unjustly, and who has damaged me out of that spite. I did it not because I wanted to, but because Our Lord commands me to — and I hope to get to the point, spiritually, where I pray for this person out of genuine Christ-like love. I know several people — all professing Christians — who have allowed themselves to become paralyzed, morally and spiritually, by hatred of people they believe to have wronged them. I’m thinking of one person in particular who has destroyed relationships because of an obsessive hatred, and the compulsion to frame themselves as a perpetual victim.

Victimhood is a source of power within elite culture, but it is a source of crippling weakness in one’s private life. One of the greatest things my father gave me was a hatred of seeing myself as a victim. Most people are victims at some point in their lives, and it was true for me too — I was bullied in late middle school and early high school. That experience defined my understanding of the way the world works. But the Christian faith I came to as an adult teaches me that I have the capacity to become a bully myself, and that I have to fight constantly the temptation to revel in victimhood.

Hear me clearly: I believe that it is important to fight bullies, and I do my best at that on this blog! But at the same time, I have to wage a battle within myself not to hate those who bully, because I could lose my soul that way. When I go to confession, I tell my confessor about instances in which I have harbored hatred towards people who have behaved badly towards me, or towards those I care about. As with so much, this goes back to 9/11 and the Iraq War with me. I allowed myself to become so consumed by anger and hatred of the Islamic terrorists who did that to us that I went along with a war that I should have known was unjust. My righteous anger at these villains caused me to hand myself over to the manipulations of bad men in my own government, who manufactured my support for this cruel and stupid war.

What a lesson that taught me! A side lesson I learned around the same time was that my anger at and hatred of the institutional Catholic Church over the sex abuse scandal cost me my faith. It turned out well for me; I would not have discovered Orthodoxy if not for that. But still, I greatly regret having allowed those passions to get the best of me, and have endeavored to learn from that unhappy experience that hatred of people who deserve to be hated for what they did (in this case, abusive priests and the bishops who covered for them) can destroy one within, and give victory to the Evil One.

I am not a good Christian. I’m still too quick to anger and too slow to forgive. But my Christian faith, insofar as it compels me to combat the drive within my heart to hate bad people, serves as a restraint. Besides, hatred, even hatred justified by evil deeds, can blind you to the humanity of evildoers. I have mentioned in this space before how a therapist I went to in the summer of 2002, after my wife begged me to get help for my overwhelming post-9/11 anger, told me that by the end of our time together, I would understand that under the right circumstances, I could have been Mohammad Atta, in the cockpit of a plane that flew into the Twin Towers.

I angrily rejected the thought. Our therapy ended abruptly that summer, for unrelated reasons. But I kept the therapist’s offensive suggestion in my mind. It took me years to see it … but he was right. And Solzhenitsyn was right when he said the line between good and evil doesn’t pass between races or classes, but down the middle of each and every human heart. Identity politics and the ideology of victimization not only results in bullying of the sort the Times reports on at Smith College, but it also wrecks the consciences of people like that self-righteous student, who could only see a normal human exchange in terms of power, and who saw — as she had been trained to see — mercy as a sign of weakness, of collaboration with evil.

If the Christian churches give themselves over to a Marxist moral analysis of the world, what could possibly stand to restrain the evil that is in the hearts of those who, in setting out to slay monsters, become what they profess to despise? These people think they are achieving moral victories, but in fact they are just rearranging their hatreds. More broadly, the elites of this country, of all races, are getting an education in hating the Other, and calling it virtue. The Other, at Smith College, are working class people who, according to the Times‘s reporting, are afraid to speak out about their mistreatment at the hands of these privileged young women students, out of fear that the youth will accuse them of some identity-politics heresy, and appeal to the Smith administration to destroy them. What is happening at Smith is the poisonous fruit of emotivism (thinking that one’s feelings are always a reliable guide to truth) and a ruling-class ideology that accords privilege by identity group.

Why has there not been a popular uprising against this garbage? In some sense, I suppose Donald Trump’s election was a popular uprising against it. But in his narcissism and incompetence, he did nothing effective to fight it, and probably made it worse. One of the reasons I am eager for the GOP to get past Trump is so that leaders who have the intelligence and moral courage to stand up to this stuff, and do so effectively, with meaningful legislation, can emerge. It seems wrong that if Smith College, and academic institutions like Smith, are to be compelled to change their ways, it will be as the outcome of Jodi Shaw’s lawsuit.

Legal judgments change practices, but they do not change hearts. I can tell you, from my unhappy experience with the Iraq War and the Catholic abuse scandal, that I did not feel empowered by my hatred. I was in fact conquered by it. Seeing myself as in some sense a victim of the Islamic terrorists, and abusive priests and contemptible bishops, made me a prisoner of my passions. In a similar way, I wonder what favor these identity politics exponents think they are doing for poor black people, and other minorities, training them to think that they have no moral agency, and no responsibility for their lives. That they are victims of malign forces beyond their control, and that there’s nothing that they can do to improve their condition on their own. I have seen with my own eyes, in a working-class white extended family I know, how that learned helplessness mires the family in poverty and defeat. If they won the lottery tomorrow, half of them would be dead or dead broke within two years, because their core problems have nothing to do with a lack of money and opportunity.

Being rich doesn’t make you evil. Being poor doesn’t make you virtuous. Nor, in either direction, does being white, black, Latino, Asian, Christian, Jewish, Islamic, or anything else. You cannot hide behind the shield of your claimed identity to escape the eyes of God, which see all. If religious leaders or anybody else prevent you from seeing this, then they are endangering your salvation. All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. All! That means you and me, and everybody else.

Finally, and once again, because the lesson cannot be repeated often enough, I offer this passage from Live Not By Lies, which tells us where identity politics tied to righteousness ultimately goes:

For example, an American academic who has studied Russian communism told me about being present at the meeting in which his humanities department decided to require from job applicants a formal statement of loyalty to the ideology of diversity—even though this has nothing to do with teaching ability or scholarship.

The professor characterized this as a McCarthyite way of eliminating dissenters from the employment pool, and putting those already on staff on notice that they will be monitored for deviation from the social-justice party line.

That is a soft form of totalitarianism. Here is the same logic laid down hard: in 1918, Lenin unleashed the Red Terror, a campaign of annihilation against those who resisted Bolshevik power. Martin Latsis, head of the secret police in Ukraine, instructed his agents as follows:

Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which class he belongs, what is his background, his education, his profession. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the Red Terror.

Note well that an individual’s words and deeds had nothing to do with determining one’s guilt or innocence. One was presumed guilty based entirely on one’s class and social status. A revolution that began as an attempt to right historical injustices quickly became an exterminationist exercise of raw power. Communists justified the imprisonment, ruin, and even the execution of people who stood in the way of Progress as necessary to achieve historical justice over alleged exploiters of privilege.

A softer, bloodless form of the same logic is at work in American institutions. Social justice progressives advance their malignant concept of justice in part by terrorizing dissenters as thoroughly as any inquisitor on the hunt for enemies of religious orthodoxy.

The post No Escaping The Eyes Of God appeared first on The American Conservative.

February 24, 2021

Smith College Hates The Working Class

Jodi Shaw’s travails at Smith College finally made The New York Times. Smith is an elite, predominantly white women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts, where tuition, room and board run $78,000 per year. The Times story seems to back up Shaw’s complaints that the school has become absolutely obsessed over race. The story gives a lot of good background to the Shaw controversy, noting that its roots are in an incident in the summer of 2018, when a black student, Oumou Kanoute, was “eating lunch in a dorm lounge when a janitor and a campus police officer walked over and asked her what she was doing there.”

You can imagine what happened next. It made national news. But, says the Times:

Less attention was paid three months later when a law firm hired by Smith College to investigate the episode found no persuasive evidence of bias. Ms. Kanoute was determined to have eaten in a deserted dorm that had been closed for the summer; the janitor had been encouraged to notify security if he saw unauthorized people there. The officer, like all campus police, was unarmed.

Smith College officials emphasized “reconciliation and healing” after the incident. In the months to come they announced a raft of anti-bias training for all staff, a revamped and more sensitive campus police force and the creation of dormitories — as demanded by Ms. Kanoute and her A.C.L.U. lawyer — set aside for Black students and other students of color.

But they did not offer any public apology or amends to the workers whose lives were gravely disrupted by the student’s accusation.

The Times piece frames the atmosphere at Smith as one where the administration is terrified of students, especially around questions of race, and treats the working-class staff like hell. A janitor told the Times that workers do their best to avoid complaining about the rich students, for fear the students will accuse them of something terrible, and the administration will take students’ side. The Times gives details of the Kanoute incident, and it involved an older janitor who doesn’t have good eyesight spotting this adult out of place, and doing as his training required, calling campus police. Kanoute was in the shadows, and the man couldn’t see well, which led him to describe the stranger (Kanoute) as “he.” Later, Kanoute accused him of “misgendering” her.

The Times writes:

A well-known older campus security officer drove over to the dorm. He recognized Ms. Kanoute as a student and they had a brief and polite conversation, which she recorded. He apologized for bothering her and she spoke to him of her discomfort: “Stuff like this happens way too often, where people just feel, like, threatened.”

That night Ms. Kanoute wrote a Facebook post: “It’s outrageous that some people question my being at Smith, and my existence overall as a woman of color.”

Her two-paragraph post hit Smith College like an electric charge. President McCartney weighed in a day later. “I begin by offering the student involved my deepest apology that this incident occurred,” she wrote. “And to assure her that she belongs in all Smith places.”

Ms. McCartney did not speak to the accused employees and put the janitor on paid leave that day.

This should have been an ordinary exchange. The Times says the older janitor didn’t even mention Kanoute’s race when he called campus police. And as the later investigation found, they had done nothing wrong. Kanoute was where she was told not to be, and the janitor didn’t recognize her as a student. He did what Smith policy required him to do. The cop came, saw that she was a student, and apologized. It was polite. Only later did Kanoute decide that she was a victim.

Smith president Kathleen McCartney made the workers feel like scapegoats, the Times reports:

“It is safe to say race is discussed far more often than class at Smith,” said Prof. Marc Lendler, who teaches American government at the college. “It’s a feature of elite academic institutions that faculty and students don’t recognize what it means to be elite.”

The repercussions spread. Three weeks after the incident at Tyler House, Ms. Blair, the cafeteria worker, received an email from a reporter at The Boston Globe asking her to comment on why she called security on Ms. Kanoute for “eating while Black.” That puzzled her; what did she have to do with this?

The food services director called the next morning. “Jackie,” he said, “you’re on Facebook.” She found that Ms. Kanoute had posted her photograph, name and email, along with that of Mr. Patenaude, a 21-year Smith employee and janitor.

“This is the racist person,” Ms. Kanoute wrote of Ms. Blair, adding that Mr. Patenaude too was guilty. (He in fact worked an early shift that day and had already gone home at the time of the incident.) Ms. Kanoute also lashed the Smith administration. “They’re essentially enabling racist, cowardly acts.”

Ms. Blair has lupus, a disease of the immune system, and stress triggers episodes. She felt faint. “Oh my God, I didn’t do this,” she told a friend. “I exchanged a hello with that student and now I’m a racist.”

Ms. Blair was born and raised and lives in Northampton with her husband, a mechanic, and makes about $40,000 a year. Within days of being accused by Ms. Kanoute, she said she found notes in her mailbox and taped to her car window. “RACIST” read one. People called her at home. “You should be ashamed of yourself,” a caller said. “You don’t deserve to live,” said another.

Smith College put out a short statement noting that Ms. Blair had not placed the phone call to security but did not absolve her of broader responsibility. Ms. McCartney called her and briefly apologized. That apology was not made public.

The story goes on to say that the workers, who weren’t guilty of anything, were treated like racist outcasts by those snotty Smith students — and the administration would not speak up for them. There’s a lot more to the story, which only tangentially focuses on Jodi Shaw, but if you’ve been following the Shaw case — I did an interview with her about it last year — you know that accusations that Smith bullies working-class people, especially by forcing them to confess their guilt as whites, is part of her complaint against the school. Great quote here, from a janitor:

He recalled going through one training session after another in race and intersectionality at Smith. He said it left workers cynical. “I don’t know if I believe in white privilege,” he said. “I believe in money privilege.”

It’s time to lawyer up nationwide, and sue these neoracist bully-boy colleges into submission. Here’s what I can’t figure out: why aren’t Republicans making an issue of this kind of thing?

The post Smith College Hates The Working Class appeared first on The American Conservative.

The Queering Of Young America

Gallup’s new poll reveals shocking information about the sexual identity of Generation Z:

And:

In addition to the pronounced generational differences, significant gender differences are seen in sexual identity, as well as differences by people’s political ideology:

Women are more likely than men to identify as LGBT (6.4% vs. 4.9%, respectively)Women are more likely to identify as bisexual — 4.3% do, with 1.3% identifying as lesbian and 1.3% as something else. Among men, 2.5% identify as gay, 1.8% as bisexual and 0.6% as something else.13.0% of political liberals, 4.4% of moderates and 2.3% of conservatives say they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender.Differences are somewhat less pronounced by party identification than by ideology, with 8.8% of Democrats, 6.5% of independents and 1.7% of Republicans identifying as LGBT.There are no meaningful educational differences — 5.6% of college graduates and 5.7% of college nongraduates are LGBT.

This is a staggering finding, whether you think the news is positive, negative, or neutral. This kind of change in something as fundamental as sexual orientation, in such a short period of time, is mind-blowing.

The trans part is the most shocking: between Gen X and the Millennials, the number of self-identified trans people has increased by 600 500 percent. Between Gen X and their children’s generation, Gen Z, the number of self-identified trans people has increased by 900 800 percent.

This is the effect of the collapse of cultural standards, and the propaganda campaign waged in the media and in schools. Today I had a private Zoom conference with senior clergy of a conservative American denomination. They said that the trans thing is exploding among their youth — kids who were raised in this conservative church — and pastors are struggling to know how to talk about it. One cleric said other pastors tell him that they don’t want to “lead” with preaching on transgenderism, for fear of alienating seekers. He said he tells them that you have to take that risk, because families and congregations are being hammered by propaganda all the time.

I agreed, and told him that pastors have to find the courage to tell the truth, no matter what it costs. The dominant culture knows what it believes about transgenderism, and does not hesitate to teach it, constantly. In my experience, parents don’t know what to say or do. If they don’t learn about it from the church, where will they learn it?

One cleric said that in his church’s youth group, some kids stood up and walked out when they begin to present the Church’s teachings on the body, sex, and gender. “They have been told in school that whenever you hear somebody criticize trans, that you are to stand up and walk out,” the cleric said.

I pointed out that this is what Solzhenitsyn told his followers in the Soviet Union to do when confronted with lies: stand up and walk out. Amazing that the other side is using the same tactics against the church!

On the Zoom call, which was to discuss Live Not By Lies, I talked about the Equality Act, which has just been re-introduced in Congress, and which is likely to pass, given that the Democrats control it. President Biden has said that he would sign it into law. If it becomes law, the Equality Act will write SOGI (sexual orientation and gender identity) into federal civil rights law. This will have devastating effects on our society. Ryan T. Anderson, the new president of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, briefly outlined them. Excerpts:

The act “updates” the law Congress passed primarily to combat racism, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and adds sexual orientation and gender identity as protected classes akin to race. So if you have any reservations about gender ideology — as even many progressives do; just ask J.K. Rowling — you’d now be the legal equivalent of Bull Connor.

Rather than finding common-sense, narrowly tailored ways to shield LGBT-identifying Americans from truly unjust discrimination, the bill would act as a sword — to persecute those who don’t embrace newfangled gender ideologies. It would vitiate a sex binary that is quite literally written into our genetic code and is fundamental to many of our laws, not least laws protecting the equality, safety and privacy of women.

More:

The Equality Act would sacrifice the hard-won rights of women, while privileging men who identify as women. If it becomes law, such men would have a right to spend the night in battered-women’s shelters, disrobe in women’s locker rooms and compete on women’s sports teams — even at K-12 schools.

Don’t believe me? Here’s the text: “An individual shall not be denied access to a shared facility, including a restroom, a locker room and a dressing room, that is in accordance with the individual’s gender identity.” So you can keep separate facilities for men and women, but you have to redefine what men and women are. Likewise, you can reserve certain jobs only for men or women — think TSA agents doing pat-downs — but you have to let a man who identifies as a woman do strip searches on women.

The act would also massively expand the government’s regulatory reach. The Civil Rights Act, it seems, is too narrow for today’s Democrats. The Equality Act would coerce “any establishment that provides a good, service, or program, including a store, shopping center, online retailer or service provider, salon, bank, gas station, food bank, service or care center, shelter, travel agency or funeral parlor, or establishment that provides health care, accounting or legal services,” along with any organization that receives any federal funding.

That’s more or less everyone and everything.

Religious institutions are very much included. Under the Equality Act, religious schools, adoption agencies and other charities would face federal sanction for upholding the teachings of mainstream biology and the Bible, modern genetics and Genesis, when it comes to sex and marriage.

They’ll be at risk, because the Equality Act takes our laws on racial equality and adds highly ideological concepts about sex and gender. But most laws on racism included no religious-liberty protections — unlike, for example Title IX, which includes robust protections for faith-based schools.

Outrageously, the Equality Act explicitly exempts itself from the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Pope Francis would be treated as the legal equivalent of a Jim Crow segregationist.

It gets worse. Medical doctors, secular and religious, whose expert judgment is that sex-reassignment procedures are misguided would now run afoul of our civil-rights laws. If you perform a mastectomy in the case of breast cancer, you will have to perform one on the teenage girl identifying as a boy. All in the name of equality. And no one knows what is required under the act to avoid committing “discrimination” in the case of “nonbinary” gender identities.

The icing on the cake? The act treats any refusal to offer abortion as “pregnancy” discrimination. Decades of conscience protections against abortion extremism at the federal, state and local levels would be undermined.

The sky really is falling. You’re not going to hear any of that in the media reporting of the Equality Act, but it’s true. If by some miracle the Republicans in the Senate all hang together, and can convince a single Democrat — Joe Manchin? — to join them, the Equality Act might be stopped this time. But sooner or later, it’s coming. Those numbers you see in the Gallup poll tell you why.

We are getting much closer to the time I wrote about in The Benedict Option, when faithful Christians and others who dissent from the new ideology are going to have to make decisions about whether or not they can continue working in their particular jobs. If you read TBO, you might recall the unnamed physician who said he would discourage his children from pursuing medicine as a career, because he can see the day coming when they will have to do conscience-violating things like perform abortions or participate in gender transitions, or lose their jobs. If you have $400,000 in medical school debt to repay, you are trapped.

If you have not begun to organize support groups and lay the groundwork for networks like Father Kolakovic did, as I report in Live Not By Lies, you should know that time is running out. The Equality Act really will regard you as no better than a Klansman if you hold to the traditional teachings not only about homosexuality, but about transgenderism. (Radical feminists who deny that male-to-female transgenders are women will be held by the same contempt in the law as a fundamentalist preacher.)

Elsewhere in TAC today, the Southern Baptist ethicist Andrew Walker writes about the meaning of the Equality Act. Excerpt:

The problem with the Equality Act does not lie predominantly in the statutory language of the bill, but in its long-term effects, further transforming the moral imagination from anything resembling a Christian social order. The Equality Act, in my view, is a symbol for the de-conversion of the West.

We see this de-conversion on at least two horizons. First, we see it in the type of moral reasoning behind the bill itself. It is a bill of aesthetics and emotion instead of reason and principle. The Equality Act would have you believe Americans relish any opportunity to discriminate. That’s false. Second, by undoing the very ontology of womanhood, the core logic of the bill contradicts key tenets of progressivism’s own advances, such as feminism. How the Equality Act can move forward with so little resistance is only understood in light of the guiding ethic of today’s progressivism. Anything that fails to rise above solipsistic phrases like “live your truth” and “you do you” cannot impede such philosophically absurd bills.

The Equality Act contains a metaphysical revolution in its pages, and it seeks the evangelization of the West. The old order was one with an ethic of objectivity, reason, fixed nature, authority, and boundaries, where organic connections and family relations were seen as guiding, normative, and persuasive, with anything opposed to these as transgressive. The revolution well underway is to make all of these metaphysical fixities not only wrong, but harmful. Thus, in the Equality Act’s telling, anything that does not champion expressive individualism or limitlessness, or derive its existence by government fiat is, well, oppressive. We are witnessing, in real time, the final displacement of a Christian account of the universe by a wholly secularized one.

The Equality Act is an assault on the Christian imagination, and this is where its long-term consequences are most dire and calamitous. It aims to reconfigure not only the foundation of family life and biological connections to gender, but to catechize, inculcating a different way of conceiving one’s place and orientation to the world. Moral imaginations are guided by normative constraints, which give them definition and direction. Ideally, a human imagination ought to comport with what is good, true, and beautiful. To educate the moral imagination is to seek a shared imagination, rooted in a shared account of the world, and therefore binding and persuasive to all of the citizens beholden to it.

Such norming norms are found within the Christian cultural framework. It creates a metaphysical order that demands compliance by all. It offers an account of human flourishing and the common good. However, the so-called Equality Act now being proposed in Congress seeks to belie all such order by completely overturning its most basic definitions. Whereas the Christian metaphysical order upholds creational boundaries as instituted by God and enshrined in the natural world, the Equality Act promotes the metaphysic of sexual autonomy and expressive individualism as the highest goods of society. So good are they, in fact, that they must be upheld in law to protect them from prosecutorial examination. The self is the sole lens of reference for all moral guidance, making the tenets of natural law and divine revelation moot, mere objects of religious fascination rather than universal appreciation.

Again, the law is a very, very big deal. But we would not be on the verge of this radical bill becoming law if not for the massive cultural changes that preceded it. The fact that between my generation and my children’s, the number of self-identified transgenders has increased by 900 percent, testifies to the final victory of the Sexual Revolution in destroying all the traditional sources of the Self. Eight years ago, I published here what has become the most popular piece I ever wrote for TAC: an essay called Sex After Christianity. Excerpts:

The magnitude of the defeat suffered by moral traditionalists will become ever clearer as older Americans pass from the scene. Poll after poll shows that for the young, homosexuality is normal and gay marriage is no big deal—except, of course, if one opposes it, in which case one has the approximate moral status of a segregationist in the late 1960s.

All this is, in fact, a much bigger deal than most people on both sides realize, and for a reason that eludes even ardent opponents of gay rights. Back in 1993, a cover story in The Nation identified the gay-rights cause as the summit and keystone of the culture war:

All the crosscurrents of present-day liberation struggles are subsumed in the gay struggle. The gay moment is in some ways similar to the moment that other communities have experienced in the nation’s past, but it is also something more, because sexual identity is in crisis throughout the population, and gay people—at once the most conspicuous subjects and objects of the crisis—have been forced to invent a complete cosmology to grasp it. No one says the changes will come easily. But it’s just possible that a small and despised sexual minority will change America forever.

They were right, and though the word “cosmology” may strike readers as philosophically grandiose, its use now appears downright prophetic. The struggle for the rights of “a small and despised sexual minority” would not have succeeded if the old Christian cosmology had held: put bluntly, the gay-rights cause has succeeded precisely because the Christian cosmology has dissipated in the mind of the West.

More:

What makes our own era different from the past, says Rieff, is that we have ceased to believe in the Christian cultural framework, yet we have made it impossible to believe in any other that does what culture must do: restrain individual passions and channel them creatively toward communal purposes.

Rather, in the modern era, we have inverted the role of culture. Instead of teaching us what we must deprive ourselves of to be civilized, we have a society that tells us we find meaning and purpose in releasing ourselves from the old prohibitions.

How this came to be is a complicated story involving the rise of humanism, the advent of the Enlightenment, and the coming of modernity. As philosopher Charles Taylor writes in his magisterial religious and cultural history A Secular Age, “The entire ethical stance of moderns supposes and follows on from the death of God (and of course, of the meaningful cosmos).” To be modern is to believe in one’s individual desires as the locus of authority and self-definition.

Gradually the West lost the sense that Christianity had much to do with civilizational order, Taylor writes. In the 20th century, casting off restrictive Christian ideals about sexuality became increasingly identified with health. By the 1960s, the conviction that sexual expression was healthy and good—the more of it, the better—and that sexual desire was intrinsic to one’s personal identity culminated in the sexual revolution, the animating spirit of which held that freedom and authenticity were to be found not in sexual withholding (the Christian view) but in sexual expression and assertion. That is how the modern American claims his freedom.

If you expect orthodox Christianity — as distinct from the false church of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism — to survive all this, you had better be drawing in and digging down in a Benedict Option way of living. And you had better start preparing yourself, your family, and your community, Kolakovic-style, for the coming persecution, once we are declared “domestic terrorists” because we will not conform. If you think I’m being an alarmist here, then tell me, where is the line you would draw, beyond which you know that persecution is upon us?

The post The Queering Of Young America appeared first on The American Conservative.

‘Live Not By Lies’ Video

Last weekend, videographer Benjamin Cabe came to Baton Rouge, and we filmed some material for use in a series of short YouTube videos on themes in Live Not By Lies. He released the first one today. Here it is:

It appears on Ben’s Orthodox YouTube channel. Some subscribers are leaving the channel — which ordinarily posts a wide range of Orthodox spiritual material — out of anger that he allows a hater like me onto it, with my hatey-hatey-hate-hate message.

Thus illustrating my point.

If you like the video, pass it on. Again, this is the first in a series.

The post ‘Live Not By Lies’ Video appeared first on The American Conservative.

February 23, 2021

‘How God Becomes Real’

I’ve been dazzled these last few days by How God Becomes Real: Kindling The Presence Of Invisible Others, the new book by Stanford anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann. You should know up front that Luhrmann doesn’t approach her work as a religious believer — she does not take a position on whether or not there are gods — but rather seeks to discern how those who believe in God, or gods, or spirits, come to do so. I was drawn to this book in part because I’m a reader and fan of her earlier work, but also because I’m thinking of doing my next book on how to re-enchant the world, living as we do in a WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) culture.

I learned a lot from this book, and having just finished it ten minutes ago, I want to share its arguments with you, because I hope you’ll buy it and read it too.

TML writes:

This is not a claim that gods are not real or that people who are religious feel doubt. Many people of faith never express doubt; they talk as if it were obvious that their gods are real. Yet they go to great lengths in their worship. They build grand cathedrals at vast cost in labor, time, and money. They spend days, even weeks, preparing for rituals, assembling food, building ritual sites, and gathering participants. They create theatrical effects in sacred spaces—the dim lighting in temples, the elaborate staging in evangelical megachurches—that enhance a sense of otherness but are not commanded in the sacred texts. They fast. They wear special clothes. They chant for hours. They set out to pray without ceasing.

Of course, one might say: they believe, and so they build the cathedrals. I am asking what we might learn if we shift our focus: if, rather than presuming that people worship because they believe, we ask instead whether people believe because they worship.

I suggest that prayer and ritual and worship help people to shift from knowing in the abstract that the invisible other is real to feeling that gods and spirits are present in the moment, aware and willing to respond. I will call this “real-making,” and I think that the satisfactions of its process explain—in part—why faiths endure.

By “real-making,” I mean that the task for a person of faith is to believe not just that gods and spirits are there in some abstract way, like dark energy, but that these gods and spirits matter in the here and now. I mean not just that you know that they are real, the way you know that the floor is real (or would, if you paused to think about it), but that they feel real the way your mother’s love feels real. I mean that people of faith come to feel inwardly and intimately that gods or spirits are involved with them. For humans to sustain their involvement with entities who are invisible and matter in a good way to their lives, I suggest that a god must be made real again and again against the evident features of an obdurate world. Humans must somehow be brought to a point from which the altar becomes more than gilded wood, so that the icon’s eyes look back at them, ablaze.

TML says that people have to “kindle” the awareness of their god, through what she calls “realmaking”:

The basic claim is this: that god or spirit—the invisible other—must be made real for people, and that this real-making changes those who do it. When I look at the social practices that surround what we call religion, I see a set of behaviors that change a practitioner’s felt sense of what is real. These behaviors both enable what is unseen to feel more present and alter the person who performs them.

Through her research, she found a few ways that are key to kindling awareness of God’s presence.

First, you have to have a “faith frame” — that is, a framework that allows you to integrate your religious beliefs into your daily life, and to allow you to navigate the cognitive dissonances. For example, the wafer and the wine at a Catholic communion service look like … a wafer and wine. But the Catholic faith frame tells the Catholic that after consecration, they are the Body and Blood of the slain and risen Lord Jesus Christ — not symbolically, but really and truly, in some mystical way.

Second, “Detailed stories help to make gods and spirits feel real.” They allow believers to bring the invisible world and the god(s) and spirit beings living within it vividly to life in their imaginations. Stories take the abstract and make it concrete.

Third, “Talent and training matter.” TML writes:

What people do and what they bring to what they do affect the way they experience gods and spirits. People who are able to become absorbed in what they imagine are more likely to have powerful experiences of an invisible other. Practice also helps. People who practice being absorbed in what they imagine during prayer or ritual are also more likely to have such experiences. This absorption blurs the boundary between the inner world and the outer world, which makes it easier for people to turn to a faith frame to make sense of the world and to experience invisible others as present in a way they feel with their senses.

Fourth: “The way people think about their minds also matters.” TML:

The intimate evidence for gods and spirits often comes from a domain felt to be in between the mind and the world, from the space betwixt a person’s inner awareness and the sensible world—the thought that does not feel like yours, the voice that feels whispered on the wind, the person who feels there and yet beyond the reach of sight. How people in a particular social world represent the mind itself—how they map the human terrain of thinking, feeling, intending, and desiring into a cultural model— shapes the way they attend to these odd moments so that the moments feel more or less sensory, more or less external, more or less real, more or less like evidence of gods and spirits.

Some combination of these foundational beliefs and practices of attention “kindle” a sense of the divine presence, no matter what your religion. Remember, Luhrmann is an anthropologist describing a phenomenon. We who hold particular religious commitments, or hold a prior commitment to atheistic materialism, may therefore believe that the god or gods that people Luhrmann studied do not exist, or are evil entities. In the book, Luhrmann writes about a Santeria community, which in my Christian view, worships gods who are really demons. Nevertheless, I found in reading TML that there is a real commonality between the way Christians practice the presence of the true God, and the way Santeria worshipers make their demonic gods real.

TML says that we in the West often misunderstand the experiences of non-Western people because of our post-Enlightenment “faith frame”:

It was the Enlightenment that made nature non-agentic, objective, and thus free of human intention, and changed forever the ontological commitments of the West. Animist worlds imagined human-like intentions throughout the world, so that all objects had agency and were different

merely in their appearances. A totemic world understood shared human-like agency only in humans and a limited number of nonhuman animals and objects with which these humans identified. And other worlds made complex mappings by analogy, all different from each other. When the naturalism of the postEnlightenment world in effect strips mind from nature, he argues, humans then feel the right to pillage the world around them.

These are cultural differences in what is real, in what way, and for whom. There are, in short, varied ways that people judge the relationship between things of the everyday world and what the faith frame treats as real, even if spirits and everyday things are always differently real. It seems likely that Western culture invites people to make a realness judgment categorically: real or not real. That is Descola’s point. The naturalness of the post-Enlightenment world creates a material world that is real and is fundamentally different from the stuff of the mind. Ultimately, G. E. R. Lloyd (2018) remarks, this is our legacy from the Greeks. Other cultures may be more likely to invite people to make that judgment on a continuum: more or less real. And so Western cultures likely worry about realness in a different way than many other peoples. The evidence still suggests that invisible beings are understood as differently real from everyday objects everywhere. It is just that gods and spirits are likely differently real from everyday objects in different places in different ways.

Put another way, our Western real/not real dualism prevents us from seeing gradations in reality that people from non-Western cultures are more open to. This is not a perfect simile, because one involves metaphysics, and the other doesn’t, but here goes: the ethnobotanist Wade Davis has written about how despite his extensive training, when he went out into the jungles of South America with natives, they could perceive far more differences among the plant life there than he could. They could discern extremely subtle differences between plants on sight. These differences were real — measurably real — which is why this is not the best simile. Still, from the point of view of a religious believer, the fact that pure materialists have a “faith frame” that rules out any evidence for a spiritual dimension to existence makes it impossible for them to see what’s really there.

So, as TML says, the challenge for religious believers is to stay within their faith frame as much as possible, for the sake of making their God or gods real. Again, by “real,” she means “feel real,” which implies no judgment about the existence or non-existence of the deity or spirits. Even if one believes that God really exists, as I do, the truth is that He does not manifest himself like my wife or my neighbor. So if I am to keep myself attentive to the reality of His existence and presence, I am going to have to work at it.

What am I going to have to do, as a Christian?

I’m going to have to engage deeply with the stories in the Bible, and in the lives of the saints. A Christianity that is only moralistic is not going to work. The life of Christ, the journeys of Paul, and the acts of the men and women of the Old Testament — they all have to live vividly in my imagination. And not just in my imagination, but in the imagination of my religious community.

Yes, I’m going to have to embed myself in a religious community built around these shared sacred stories. That community must have a shared sense of what these stories mean, and how we are to relate to them. The community must have a clear set of rules for what it means to be a part of it. And there has to be established rules for interacting with that “invisible other.” People have to have some way of knowing when the community believes God to be present in a special way (e.g., for Catholics, after the consecration of the bread and wine; for charismatics, when people start speaking in tongues, etc.) And, there have to be shared ways of knowing when God responds. This is how people know that what they’re doing is real, that it’s not just make-believe.

Living out the faith frame in community, with others who share your beliefs, both affirms them and makes them feel more real to you. It jumped out at me that in TML’s research, it matters that these faith communities make demands on their members. You can’t really be “seeker-friendly” in the sense of making minimal demands on people, and expect the members of the community to develop a strong sense of God’s reality.

If I’m going to practice the presence of God, then I can’t just sit around and wait for it to happen. I’m going to have to work at it. TML says that people who have stronger imaginations find it easier to feel the presence of the divine, but that everyone can get better at it through training. She relates this experience that happened to her in the 1980s, when she was in England working on her PhD. She was studying a group of witches. TML reports that as she trained her mind in the same way the witches were doing, inexplicable things began happening to her. For example:

I was sitting in a commuter train to London the first time I felt supernatural power rip through me. I was twenty-three, and I was one year into my graduate training in anthropology. I had decided to do my fieldwork among educated white Britons who practiced what they called magic. I thought of this as a clever twist on more traditional anthropological fieldwork about the strange ways of natives who clearly were not “us.” I was on my way to meet some of them, and I had ridden my bike to the station with trepidation and excitement. Now in my seat, as the sheep-dotted countryside rolled by, I was reading a book written by Gareth Knight, a man they called an “adept,” meaning someone deeply knowledgeable and powerful. (The book was Experience of the Inner Worlds.)

The book’s language was dense and abstract. My mind kept slipping as I struggled to grasp what he was talking about, and I wanted so badly to understand. The text spoke of the Holy Spirit and Tibetan masters and an ancient system of Judaic mysticism called Kabbalah. The author wrote that all these were so many names for forces that flowed from a higher spiritual reality into this one through the vehicle of the trained mind. And as I strained to imagine what it would be like to be that vehicle, I began to feel power in my veins—really to feel it, not to imagine it. I grew hot. I became completely alert, more awake than I usually am, and I felt so alive. It seemed that power coursed through me like water through a chute. I wanted to sing. And then wisps of smoke came out of my backpack, in which I had tossed my bicycle lights. I grabbed the lights and snapped them open. In one of them, the batteries were melting.

TLM goes on:

Yet it was not all about training. Practice did not explain my experience when I took that train into London, even taking into account my determined attempt to imagine my way into that author’s world. In fact, people sometimes went looking for books on magic when they had experienced an out-of-the-blue event—an intense sense of invisible presence, for instance—that they felt they could not explain. At the same time, it was also clear that anomalous experiences were more common among those who practiced: those who did the exercises and rituals again and again. What I saw seemed more like an orientation to inner experience, which someone might have by temperament but could also develop through practice. I learned that in the London world of modern magic, the following was commonsense: If you wanted to do magic, you had to practice magic. If you wanted to feel power flow through you and to direct it toward a source, you had to do it again and again, and you had to train, preferably under a seasoned elder.

Some people were naturally better than others. Magicians spoke as if there were people who were naturally good at being psychic, and people who were naturally good at doing rituals. The psychics (they said) did not feel things in their body. They simply knew things and had insights that others did not. Those who were good at doing magic were able to have the distinct sense that power was present. They could feel it moving through them, and they felt as if they could direct it. Those who practiced would get better. People routinely said that over time they experienced power more intensely. Those who practiced found that their mental images grew sharper, and they were more likely to report unusual phenomena: they felt the power, they heard the gods, they saw the spirits.

As I began to read more intensively, I started to realize that what magicians did in their training could be found in other spiritual practices around the world: in Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Judaism, shamanism, even spirit possession. The capacities to visualize and to sink into trance-like states seemed to be learnable skills. I began to think that mastery of those skills was associated with intense spiritual experience and the sense that gods and spirits felt real.

And in many ways what they experienced was similar to what the magicians experienced, and they said remarkably similar things about talent and training. The Christians sometimes said that after they began to pray actively, they not only experienced God more vividly, but their inner world became sharper and felt more real, as if those features were side-effects of training. They knew that practice mattered. They thought that powerful experiences were more common in the lives of those who prayed actively. They also knew that predisposition mattered. They were clear that some people had a hard time hearing God, even when they prayed, and they knew that some people had experiences that came out of the blue.

This resonates with my own experience in Orthodoxy. The times I feel farthest from God are inevitably times when I have stopped praying regularly. It really is true that you get out of Orthodoxy what you put into it. When I was in college, and in my early twenties, I longed for religious experience, but I did not want to work at it. I did not want to sacrifice anything for it. I wanted a mystical version of cheap grace. The laws of the spirit world don’t work like that. God loves you whether you feel it or not, but if you want to be truly changed, to dwell in the Spirit, you are going to have to work. This is not about earning salvation; rather, it is about practicing the presence of God, of deepening your relationship with Him, of dying to self so that Christ can live more completely in you. This doesn’t just happen. It takes prayer, fasting, confession, repentance, communion — the same tools that the Church has always given us.

TML says that real-making requires cultivating our attention to sensual details. We have to get out of our heads. We have to learn to see, really see, the sunset, and see not just the beauty of the dusky light on the clouds, but make the imaginative connection between that and its Maker. We have to train our eyes and our ears to pay attention. Again, moralistic religion can’t help you here. I’m not saying that morals don’t matter — not at all! — but only that making God real requires engagement with the body through its senses. The more abstract our sense of God is, the harder it will be to know Him.

Another interesting point: the degree to which we can feel God’s realness depends on how we regard the mind. She says that Westerners usually believe that the mind is like a “citadel” separate from the world. For people in non-Western cultures, the boundary between Mind and World is far more porous — and that helps them be more perceptive of spiritual realities.

TML writes of a study she did comparing how Evangelicals in California, India, and Ghana experienced God’s presence in worship. What she found was that the Americans were more individualized in their experience of God, but the Evangelicals in India and Africa experienced God much more vividly. She writes:

I don’t think that these different rates simply reflect different ways of talking about God. I think that different ways of attending to experience kindle God in different ways. In all these churches, God spoke through the Bible and through people and in the mind. In all these churches, God was also represented as speaking out loud to ordinary humans—after all, God spoke out loud to Abraham, Moses, Ezekiel, and John of Patmos, and evangelical prayer manuals are filled with vivid, auditory examples of God communicating in words the ear can hear.

Yet because of the way that congregants thought about their minds, God feels real for them in different ways. In Chennai, He felt more real through people. In Accra, He felt more real in the experience of the body, in the felt power of the Holy Spirit. For the Americans, their experience of God was a little less palpable. For them, God seemed to feel less external and more mental. Or, to use the Macmillan dictionary definition, a little less real.

There’s so much more to the book than I’ve indicated here. I just wanted to share with you what excites me. I’m going to be going more deeply into this on my Daily Dreher newsletter tonight and this week. If you would like to consider subscribing — five dollars a month, or $50 per year, for five newsletters per week — check out how to do that here. It’s not a newsletter about politics or the culture war, but about faith, art, and the things that make life worth living.

If you’d like to know more about Tanya Luhrmann’s thought, here’s a short interview with her from 2019:

The post ‘How God Becomes Real’ appeared first on The American Conservative.

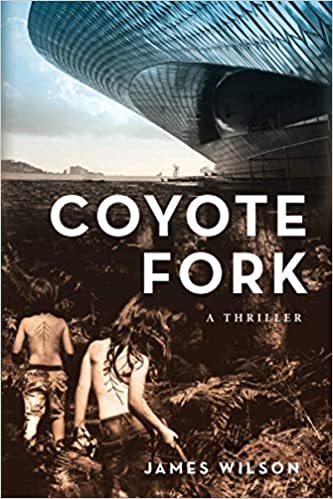

James Wilson’s ‘Coyote Fork’

The English novelist James Wilson’s latest work, Coyote Fork, is a taut thriller about a British journalist who finds himself in Silicon Valley, on the trail of killers. What he and his traveling companion Ruth — a philosophy professor who is being severely harassed by a woke student mob — discover is a mystery that has to do with nothing less than what it means to be human. I found myself unable to put the book down, not only because Wilson keeps the action moving propulsively forward, but also — indeed, mostly — because like in Umberto Eco’s The Name Of The Rose, the search for the truth of what happened to a dead person takes the protagonists on a philosophical, even metaphysical, journey. It’s a journey that has everything to do with the way we live today, in a culture dominated by Big Tech.

I e-mailed Wilson at his home in London, and asked him if he would be willing to answer some questions about the novel, published last year by Slant Books. He kindly agreed, and e-mailed his replies. The interview is below. The last question brought a response from James, about his religious beliefs, that surprised me!

RD: The themes of Coyote Fork — techno-utopianism and progressive cancel culture — could hardly be more timely. What made you decide to write about them?

JW: Like many people during the last decade, I found myself becoming increasingly uneasy about the power of the Internet (though that didn’t stop me using it!). Then, a few years ago, two developments tipped that unease into outright alarm. One was observing the impact of social media on people close to me: how it narrowed sympathies, heightened intolerance, changed decent human beings into self-righteous bullies. The other was an apparently trivial personal experience: travelling home after dinner with some friends in north London, I happened to look at my smartphone. There, blazoned across the screen, was a weather forecast for Sofia. I have never been to Sofia. I had no plans to go to Sofia. But one of our hosts that evening is Bulgarian. I could only conclude that Google hadn’t merely tracked my whereabouts, but in some sense “knew” who I was with.

I decided to dig deeper, to try to discover more about our new Tech masters. What I found convinced me that we are in the middle of the most momentous and far-reaching revolution in human history. Beneath the mesmerising surface spectacle – the Zoom calls, the breath-taking graphics, the instant streaming of any piece of music you want, the excited chatter about colonizing Mars – something much more fundamental was going on. And to me, anyway, that something is profoundly disturbing.