Rod Dreher's Blog, page 651

November 5, 2015

The Value of Submission

The Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld considers Michel Houllebecq’s new novel, Submission, which is now out in English (Soumission is the French title). Excerpts:

Soumission is the title of a new book by the formidable French writer Michel Houllebecq. Judging by everything I had read and heard, I thought it was a description of all the terrible things that would happen in France under a Muslim Government.

It is not. Mainly it is a devastating—devastating, I say—critique of modern French, and in many ways Western, society. For a millennium, people used to worship the Christian God. Next came patriotism as represented, in France, by the great poet Charles Péguy. By now, though, both of these ideals are stone-dead. The outcome is a society that recognizes no higher law. Nothing that is sacred and stands above the desires and caprices of individual people. One in which “emancipated” women, competing with men and in many ways behaving like them, have nothing to offer them except a good bl**job or a nice a*s. In which, in other words, women are as bad, or as good, as prostitutes.

This is a world in which the family is supposed to be based on “love,” but in which a very large percentage of all marriages end in divorce. In which there are very few children—throughout the book, Houllebecq does not mention even one. In which adults leave the care of their aged parents to uneducated foreign workers with whom, in many cases, they cannot even communicate. A society which claims to be free, yet in which it is impossible for anyone to be a more than a few days away from home without being flooded by all kinds of letters from the authorities.

Van Creveld narrates the plot of the book, and says that a particular character submits to Islam, and has no regrets:

In view of what Western society has become, is there any reason why anyone should?

Over to you, Jones.

Benedict Option Baby Steps

A reader writes this pretty great letter:

My name is Matt and I come from an American, evangelical, Southern Baptist background in Louisville, KY. In early October I was going through a kind of spiritual crisis (“crisis” may be too strong of a word), not in danger of losing my faith, but in search of some foundations. I was asking myself questions like: at bottom, what does my faith stand on? Why do I believe what I believe? If my final authority lies in the sacred writings, how do I defend that belief? Is it circular? Isn’t everyone’s ultimate standard of truth defended in a circular way? If so, what tips the scales to the Bible? Is this way of thinking even the right way? The best way? I was asking questions about epistemology, but also another kind of question: What does the Christian life look like? I told an older friend and church member I meet with twice a month for coffee, “There has been over 2,000 years of people writing about this, someone must have passed this wisdom on somewhere.”

I had just finished reading James K. A. Smith’s book, “How (Not) to be Secular” (the first book I’d read by him) and I also was reading Esther Lightcap Meek’s, “Loving to Know.” I have listened to hundreds of John Piper’s sermons and I sat under the preaching and professorship of Dr. Russell D. Moore for a couple years (just more background information to clue you in to the kind of teaching I’ve absorbed). Somehow I ended up at the Mere Orthodoxy blog and read Jake Meador’s post from 10-7-15 titled, “The Benedict Option and the Pace of Middle Class Life.” The paragraph that got me was this: “The problem Gumm is getting at is a sort of awful cycle that many middle-class Christians will likely understand: We feel the absence of a spiritual rootedness in our lives that exists not only in our hearts and minds, but in the stuff of daily life. We feel a sense of aimlessness or purposelessness in our work; we feel frustrated by the lack of intimate relationships in our church; we feel isolated in our attempts to raise and educate our children.” When I read that I said to myself, that is me.

From there I discovered your blog and the things you’ve been discussing about the Benedict Option. I had never been to your blog before, but I did have “The Little Way of Ruthie Leming” on my “to-read” list for a long time (it’s on my desk now). I immediately gravitated to the things you were saying and it felt like someone had reached out a hand as I was being pushed along by a raging current. Thank you for that! After reading the James Smith book I decided that I wanted to try, within my family, to focus more intently on the church’s liturgical calendar to create a rhythm in our lives that might shape the social imaginaries we develop. I continued to read your blog and then I read “Desiring the Kingdom” by James Smith. I felt like I had been primed for many years for that book. Between John Piper’s focus on the affections, your stuff on the Benedict Option, my growing love of literature (like Dostoevsky, Hugo, David Foster Wallace, Flannery O’Connor, etc.), a church I started attending in 2012 that is the most liturgical Baptist church I’ve ever seen (I didn’t know what the word “liturgy” meant before I started going there), my move away from television (because of the way images powerfully shape the way we see the world), and my deepening friendship with a co-worker that has led me to seeing the importance of face-to-face human relationships over mediated ones. All of that made “Desiring the Kingdom” everything I wanted to express but didn’t have the words for plus a holistic human anthropology to support it.

So, I am now attempting to do what Jake Meador brought up in his blog post: small steps for a busy family with a 3-year-old toward something like the Benedict Option for us. That means a focus on the liturgical calendar (actually celebrating Reformation Sunday with my family crafting our very own Luther’s Rose while eating gingerbread cookies and listening to “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”). Also, structuring my day around prayer (morning, noon, and evening) by praying through the Divine Hours (http://annarborvineyard.org/tdh/tdh.cfm). I’ve added a time of simple family worship at the end of our day at home (read a text of Scripture, recite the Apostle’s Creed, pray). I’ve taken up praying the Jesus Prayer, which I heard about from you. This was especially new to me. Praying through pre-written prayers is one thing, but the Jesus Prayer especially goes beyond the traditions of my background. But once I tried it, I knew that there was something to it. The way it centered my mind on Christ was unlike any other spiritual practice. I recently purchased a prayer rope as well.

Now, this gets to the main problem in all of this. One of the things you emphasize in your writing is belonging to something bigger than yourself that defines you, as opposed to the casting off of all authority and becoming whoever I decide I want to be. Yet I feel like I’m making this up as I go and not stepping into a pre-existing tradition. Though the calendar, the Divine Hours, and the Jesus Prayer are old traditions, there is a sense in which it feels like these things don’t belong to my tradition and I’m just grabbing things from here and there. Then there is the fact that there isn’t anyone in authority guiding me in this (at least not in my church, like a spiritual Father instructing me to pray 500 Jesus Prayers each day). If I told my pastor what I was doing he’d probably say, “Way to go!” I’m not sure what he’d say about the Jesus Prayer and prayer rope. I should probably ask him. On top of that, it isn’t like many other people in my church are doing the same things. I mean, maybe people are praying (are they???), but it’s so unstructured that everyone just kind of does their own thing with prayer. This, in my opinion, separates each individual member to “do” Christianity in wildly differing ways such that it’s difficult to feel a connection, spiritually, with the people around you. The connection is mainly that we believe the same doctrines. If we talk about prayer, we are much more likely to talk about how we really should pray more, and how we will try to do better at that this week. Of course, what the Christian life looks like may be different from person to person, especially given various vocations and family dynamics, but shouldn’t there be practices that connect all of us? That we should be able to assume everyone else has participated in because they are Christians (and not just on Sunday)? Practices that we have in common because we have a history in common? Practices that are passed down to us from the church that function broadly as discipleship, such that every Christian would be comfortable telling an unbeliever to look at their life as an example of what a Christian life is about. Maybe I’m wrong about this.

Anyway, I thank you for your insights. I’m currently reading through Dante’s Divine Comedy while listening to the Great Courses lectures on it. Then I plan to read your book on Dante. I’m curious what you think about my Benedictine baby steps, but I am not assuming you will be able to write back. Mostly I just wanted to share my story with you and my gratitude.

Pax et bonum!

This letter gets to a core question of the Benedict Option. I will repeat the e-mail I received the other day from an Orthodox Christian reader, a longtime convert from Evangelicalism. I’ve slightly edited it for the sake of privacy:

I am fascinated by the move toward and longing for “traditional” Christianity amongst Evangelicals. My experience concurs that these folks are hungering for a more traditional faith and church life, and are disenchanted with what they have received from Evangelicalism. That is my observation from over 20 years … only that I find that most such folks hunger for a “traditional” Christianity but ONLY on their own terms. A “traditional” Christianity, but one which leaves them as the sole authority and judge over what that “tradition” actually is. For example, on such foundational things as church authority, worship, sacramental life (eucharist, particularly the major stumbling block of “closed communion”, confession, ordination (particularly women’s ordination, and which I believe will inevitably include homosexual as well), and such fundamental paradigm shifts such as what it means to be the “Body of Christ”, with respect to membership thereof. Most of the members of these congregations move freely in and out of “traditional”, or on to the next fad, depending on their needs and desires of the moment).

For many Christians like this, “traditional” is but a thin veneer of the “historical” that soothes the spiritual conscience by remaining utterly “Evangelical Protestant”, only now offering weekly communion, saying a creed together, putting on a stole for the “historic/traditional” portions of a service, proof-texting a few select Fathers of the church quotes here and there to legitimize the “traditional” branding. But otherwise, keep rock bands, sola Scriptura, hip, coolness and cultural relevance as supreme values — but above ALL the tyrannical reign of the “individual” and one’s “personal relationship with Jesus” over and above any real traditional concept of “Church” and life in Christ.

The question, it seems to me, is whether it is possible to do the Benedict Option without submitting to an authoritative Tradition. The answer to that — well, my answer to that — is that I don’t know. I am doubtful about it, for precisely the reasons the Orthodox reader said. I could be wrong. That’s why I am looking forward to doing the real reporting for the Benedict Option book: so I can see what people are actually doing, and how it’s working for them. I must repeat here that in my experience, most American Christians, even those who are communicants of an ancient church, are just like the Evangelicals criticized by the Orthodox reader. That is, they don’t want to submit to their authoritative tradition either, but reserve the right to pick and choose as suits their sovereign Selves.

Plus, I do not want to discourage folks like the Baptist reader, who longs for what the ancient Christian tradition offers. It is wrong, I feel, to make the perfect the enemy of the good. I am strongly encouraged by the Baptist reader’s “Benedictine baby steps,” as he calls them, and want to strongly encourage him in the project. I would also encourage him to talk to his Christian friends about these practices, and ask them to join him and his family in committing to doing them. He’s right: we need to be able to pray like this together. One of the things I’m going to have to do in the Benedict Option book is to demonstrate how necessary structured prayer and worship, and sustaining traditions, are to holding on to the faith across the generations. I wonder, though, what the Baptist reader believes about the strength of his tradition in the face of the dis-integrating forces in the broader culture. I don’t ask this in a hostile way; I genuinely want to know.

We know from the Pew surveys that Evangelicals are doing a much better job than Catholics in holding on to basic Christian moral teachings. A Catholic friend wrote to me last week, “I keep wanting to agree about Evangelicals and Tradition” — that Evangelicals, lacking an authoritative tradition, aren’t going to be able to hold on through what’s coming — ” but on the battles of the moment, it’s still the case that they’re hanging tougher than the RC by far. Sola Scriptura has big, big long-term weaknesses, but at the moment their lack of a ‘development of dogma’ idea that can be exploited by, well, Jesuits is actually a big strength.”

And yet, when I praised an Evangelical friend recently for the strengths within his tradition, regarding raising kids with a strong knowledge of and commitment to Scripture, he told me that this is no longer the reality on the ground. I keep hearing this from other Evangelicals, who indicate that their churches have really suffered from the whole “seeker-friendly” approach, which downplayed or all but dismissed Evangelical distinctives, in particular a strong knowledge of and submission to Scripture.

Anyway, I getting far afield. I’d like to know what you readers would say to this Baptist reader, a man who is eager to connect to ancient Christian traditions and practices, but who is feeling stymied by the lack of believers walking with him on this path within his church and tradition. I don’t have strong, clear answers now, because I simply have not done the deep research and thinking to give him one. I thank you readers in advance for your insights. Because this reader’s letter, and his questions, are so serious, I’m going to be selective in which comments I publish. Be critical if you like, but if you aren’t genuinely interested in what this Evangelical man is struggling with, don’t bother commenting, because I’m not going to post it. Letters like this reader’s, and comments from other readers on it, really do help me in my book projects. I take them seriously, and ask you to do so as well.

November 4, 2015

Bernie Sanders, (National) Socialist?

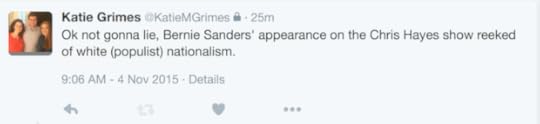

My favorite theologian gets in touch with her inner Myrna Minkoff, and speaks Truth to Power:

If that pale, penis-having reactionary Ross Douthat had a theology degree from Boston College like Minkoff here does, he would be able to see these fascist threats coming, and alert his readers. Keep saying things, Myrna. I beg you.

Readers, momentarily Your Working Boy will be off to New Orleans the New Jerusalem to cover a two-day criminal justice conference. There will be wine cakes, I am sure, and communiss. Stay tuned.

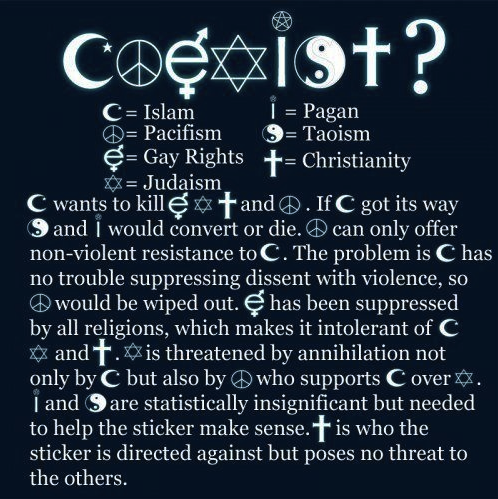

That Stupid ‘COEXIST’ Slogan

The Transgender Wedge

The overwhelming rejection last night of an LGBT non-discrimination ordinance by Houston voters suggests that the “transgender bathroom” phenomenon could be a powerful wedge issue in the 2016 presidential race.

As Rice University political scientist Mark Jones told the Atlantic‘s Russell Berman, opponents of the defeated HERO ordinance have said that they would accept a non-discrimination ordinance that exempted bathrooms and locker rooms. I believe that is possible. Most people in this country are a lot more accepting of lesbians and gays than they are of transgenders — and even then, I believe Americans would tolerate transgenders, but absolutely do not believe trans people have a civil right to use bathrooms and locker rooms belonging to the other biological sex.

This offends LGBT activists, of course, but it is by no means an unreasonable stance. The “transgender” part of the LGBT coalition represents a radical departure, even from same-sex attraction. After all, however disordered orthodox Christians may believe same-sex attraction to be, at least they affirm the reality of gender. Transgender denies even that.

I am reminded of a conversation I had earlier this year with a Catholic priest friend about the challenge he faces in campus ministry dealing with refugees from the Sexual Revolution. From the blog I posted back in May about it:

What Rieff is saying here, sometimes amid thick jargon, is that what was distinctive about Christianity from the beginning is a spirit of asceticism, especially sexual asceticism. As Rieff makes clear, Christianity did not prescribe “crude” sexual renunciation (i.e., total denial of the sexual instinct), but rather controlling it, reining it in to make it serve higher spiritual purposes. If you can master your sex drive, the theory went, then you can master any other passions that, unreined, will destroy you and the possibility of community.

Rieff’s prophetic point is that Western culture has renounced renunciation, has cast off the ascetic spirit, and therefore has deconverted from Christianity whether it knows it or not. In bringing this up with my priest friend, I asked him why he thought sex was at the center of the Christian symbolic that has not held.

“It goes back to Genesis 1,” he said. “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. Then he told them to ‘be fruitful and multiply.’ We see right there in the beginning the revelation that male and female, that complementarity, symbolizes the Holy Trinity, and in their fertility they carry out the life of the Trinity.”

In other words, from the perspective of the Hebrew Bible, gender complementarity and fertility are built into the nature of ultimate reality, which is God. Our role as human beings is to strive to harmonize our own lives with that reality, because in so doing we dwell in harmony with God.

“Do you know what the word ‘symbol’ means in the original Greek?” he asked. I said I did not.

“It means ‘to bring together,’” he said.

“To integrate,” I replied.

“Yes. Now, do you know what the antonym for symbol is?”

“No.”

“It is diabolos, which means to tear apart, to separate, to throw something through another thing.”

“So when something is diabolic, it means it is a disintegrating force?”

“You could say that, yes,” he said. “All the time I’m dealing with the fallout from divorce and families breaking up. Kids who don’t know their fathers. You should hear these confessions. It’s a huge deal. You can see the loss of the sense of what family is for, and why it’s important.”

He said that the students he works with are so confused, needy, and broken. Many of them have never seen what a functional, healthy family looks like, and have grown up in a culture that devalues the fundamental moral, metaphysical, and spiritual principles that make stable and healthy family formation possible — especially the belief that the generative powers of sex, within male-female complementarity, is intimately related to the divine nature, and the ongoing life of the Trinity. Nobody has ever explained it to them, he says. If they’ve heard anything from the Church, it’s something like, “Don’t do this because the Bible says not to” — which is not enough in this time and place. And many of them have never, or have rarely, seen it modeled for them by the adults in their lives.

To many, the idea that people would be unnerved by transgenders using opposite-sex bathrooms and locker rooms seems like ignorance and prejudice. To many others, though, it amounts to a basic recognition of the reality and meaning of gender difference. To accept homosexuality and transgender is diabolical in the sense that the priest means above: dis-integrating the bonds of society. Transgender is much more significant in this respect than homosexuality, because it denies the most basic biological reality of all.

The Obama administration and the Democratic Party, at least at the national level, has gone all-in for the LGBT agenda. This week, the Education Department announced its intention to file civil rights lawsuits against public schools that do not allow transgender students to use locker rooms and bathrooms for their preferred gender. No compromise is possible, says Team Obama, rejecting an Illinois school district’s proposal to create a separate changing area in the girls’ locker room for a transgender student.

This is what it means for sexual radicals to have control of the US government. They tell your local public school that if it doesn’t allow teenagers with penises to use the girls’ locker room and bathroom, or teenagers with vaginas to use the boys’ locker room and bathroom, the United States will come down full force on them in court. This is how revolutionary the Democrats are — and Hillary Clinton is its Madame DeFarge.

Of course the gutless Republicans will not talk about the federal government bullying public schools to open their locker rooms and bathrooms to transgenders, because they’re terrified of being called bigots, and upsetting their big business patrons. Nevertheless, we know that if Hillary Clinton becomes president, she will continue to wage war on reality, and on the sensibilities of localities, in the name of the Revolution. However weak and vacillating a Republican president would likely be on these issues, he would be better than the Democrat.

The “transgender bathroom” issue symbolizes something far more profound than the ickiness of a penis-haver in the girls’ room. It represents the degree to which the US government is willing to go to enforce a radical view of reality itself on an unwilling population. It’s a big deal.

Fundamentalism & the Benedict Option

A reader sent a thoughtful letter about the Benedict Option. The reader agreed to let me publish it so long as I took out certain identifying details, which I was happy to do:

I’m hopeful for the possibilities of the Benedict Option conceptually but fearful about implementation, so I thought I’d share a bit of my story with you.

There are bleak possibilities of a Benedict Option gone wrong. I grew up in a fundamentalist church and converted to Catholicism during college. You’ve mentioned meeting people who were burned by fundamentalism, so let me add myself to the chorus of wounded people. I arrived in adulthood with little understanding of why orthodox Christian doctrine is important or what its existential significance is. I knew about the lines we were supposed to toe in order to avoid expulsion, but little about hope. It has taken me years to start getting over some of the traumatic abuses of authority that I witnessed in the fundamentalist environment, particularly as it related to my femininity. To this day I am less trusting of Evangelical men than non-Christian men because of the morally skewed vision of gender roles I expect they were indoctrinated with. Keeping young women in line was necessary to keeping the community together, and this sometimes meant the authorities turning a blind eye to the physical abuse of wives and children within the community. The whole experience left me rather tattered. Authority issues are certain to be serious for any community that clings to its own life.

The idea of Christian community is also potentially threatening to me because I am bisexual. For a while, after I had become Catholic, I rejected what I had heard in Evangelicalism about homosexuality and had a girlfriend. Through a couple years of studying, I’ve come to the conclusion that there exists a traditional Christian stance on homosexuality that is not just bigotry or social engineering, but I certainly never had any prior idea of the metaphysical significance of gender within Christianity because the Evangelical ‘stance’ on homosexuality was nothing but a political signifier in a community that existed only for its own self-preservation. I’m still in a quandary about how I should live my life, but having learned about the body of traditional Christian teaching on sexuality, I certainly think it raises metaphysically and morally substantial issues, which I didn’t before.

I strongly urge you to consider how a Benedict Option would deal with children who are unable to adopt conventional norms. In communities with rigid norms, it can be difficult for gays or any other ‘different’ person to even truthfully acknowledge their own inner experiences (prior to any behavior). This creates a barrier between the individual, God and other people. I’ve seen other people who were raised similarly to me utterly reject Christianity or become outspoken anti-patriarchal activists of the SJW ilk. I reject this kind of activism as spiritually detrimental, but it’s tempting when one has had legitimate grievances.

I’ve also seen BenOp-like situations work well: the Christian community at the Evangelical college where I studied, as well as various Catholic ministries. While there were still some institutional problems associated with trying to set boundaries in the community, at my college I experienced a community that was formed around Christianity as a joyful and meaningful way of life, not just something that desperately needs preservation. I found friendships that I am certain were God’s way of saving my faith. The success of this community was partly because professors designed our education to mitigate the intellectual and spiritual ill effects of the fundamentalist communities many students were raised in. In general, I think intentional community must have the flexibility to allow for all the flaws and sins of human nature, because rigidity leads to the worst abuses.

I’ve said nothing you haven’t heard before, but the moral of my story is to encourage you to carefully consider the mistakes of the ‘Benedict Options’ that have already been tried, lest all you have to show for the BenOp is a future generation of Rachel Held Evanses. However, with careful attention to the structure of the community, it may truly be possible to for people create Benedict Options that truly embody what you envision. Since I’m a current resident of [place withheld for privacy reasons], it would make me terribly happy to see some sort of BenOp community forming around here! This also leads me to the thought that the Benedict Option must not only appeal to educated middle-class people. I find comfort in sharing some of the difficult aspects of my story with you because, in a way, it expresses a hope for what you want to see realized in Benedict Option communities, which is the realization of abundant life.

What a great and encouraging e-mail. I also received this from another reader, this one an academic:

I’ve seen you wonder on many occasions about how to avoid fundamentalism in BenOp communities. I’d like to give you my thoughts on this, as someone who is a cross between a sociologist and a moral theorist. What I have to say boils down to a pithy motto: “There are no fundamentalists on feast days.”

You should look more deeply, I think, at Philip Rieff. His sociological theory contrasts interdicts (“thou shalt nots”) against remissions (releases from interdictory controls). Rieff is concerned about how an interdictory culture becomes as remissive one, as he believes our culture has become. But he does not stress that the preservation of authority depends on the proper combination of interdicts and remissions. A robust and valid, respected and legitimate authority has the power to issue interdicts, but the continuity of the respect and legitimacy that it inspires depends on the presence of remissions. A good authority allows times of relaxation from the rules, whereas an authority that intensifies its interdicts without allowing for releases becomes tyrannical.

What we call fundamentalism, what Evangelicals are so scared of, is an authority that is all interdicts and no remissions, all rules and pressure to conform without respite or breaks. It is a pressure that allows no rest – think of Israel in Egypt (Ex. 5).

The strange thing about Protestantism is that it has neither fast days nor feast days. Orthodoxy, which both of us practice, of course has these. We are nearing the fast of the Nativity, which ends in the feast week of Christmas. We fast laboriously during Lent, but then we celebrate Pascha. Can a fundamentalist celebrate the paschal feast? Can a fundamentalist celebrate Christmas as a feast week? No! This is because the fundamentalist does not allow for the interchange of interdicts (eg, fasting requirements) and remissions (feast days), but lives in a church that has abolished both fasting and feasting, as Protestantism by and large has, and replaced these with a stricter moral and doctrinal code, a demand of complete conformity with a different moral standard that is still called Christian.

How do you avoid fundamentalism? Insist that a BenOp community have releases from controls; insist that it have feast days, times of relaxing the rules. Orthodoxy is hard, but it is also gentle, which is to say that it knows that believers must have rest from their work. Fundamentalism is the abolishment of rest, the abolishment of freedom – and thus it is harder, in some ways, than Orthodoxy.

Long live fasting and the discipline of the body for prayer; long live feast days as well, so that the God for whom we fast and to whom we pray retains his character in our lives as merciful.

I hope you find this helpful.

I do! It says to me that one practice that Evangelicals can adopt from the early church (practices still observed in Orthodoxy) is feasting and fasting according to the Christian calendar. Evangelical readers, help me out here: is there any theological reason that you cannot observe periods of fasting? (By “fasting,” Orthodox Christians don’t mean doing without any food, but rather abstaining from meat and dairy, and, in some cases, large meals). Maybe some Evangelicals see it is a matter of works-righteousness (i.e., trying to work one’s way into heaven), but remember, Jesus fasted too. Besides, the point of fasting is to train the body to put spiritual goals ahead of bodily desires.

The first reader’s letter is a great reminder to me, who has never experienced fundamentalism, why it is so dangerous. It offers a “total solution” to the problem of human freedom. Let me quote again Isaac Bashevis Singer:

The powers that assail us are often cleverer than every one of our possible defenses; it is a battle which lasts from the cradle to the grave. All our devices are temporary, and valid only for one specific attack, not for the entire moral war. In this sense I feel that resistance and humility, faith and doubt, despair and hope can dwell in our spirit simultaneously. Actually, a total solution would void the greatest gift that God has bestowed upon mankind – free choice.

November 3, 2015

Houston: Ladies Rooms Are For Ladies

Big win for religious liberty in Houston tonight:

Houston voters rejected a controversial measure Tuesday that would have barred discrimination against gays and transgender people after an 18-month battle that pitted advocates of gay rights against those who believed they were defending religious liberty.

The vote had been expected to be close. But with about 30% of precincts reporting, the measure was failing, 62% to 38%, and the Associated Press called the election for the measure’s foes.

The Houston Equal Rights Ordinance was initially approved by the City Council in May 2014. But opponents sued. In July, the Texas Supreme Court ordered the city to either repeal it or place the measure on the ballot.

Texas is one of 28 states that does not have statewide nondiscrimination protections — although major cities have adopted policies, including Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth and San Antonio.

Houston Baptist pastor Nathan Lino gives the background of today’s vote:

Evangelicals nationally may not realize this ordinance is directly related to the Houston city government issuing sermon subpoenas to five Houston pastors in the Fall of 2016; the fight over this matter has been going on for eighteen months. The Mayor of Houston had this ordinance put into law by the City Council. Fortunately, city law also allows Houston citizens to collect a certain number of signatures on a petition and force a city council decision to be brought to a public vote. Thousands more signatures were collected than the minimum necessary. Every signature was accompanied by detailed and verified information. The petitions were notarized. The Mayor promptly had her City attorney invalidate the signatures. She simultaneously attempted to bully Houston pastors by issuing far-reaching subpoenas to five high profile pastors, demanding all sermons, emails, letters and text messages. Houston pastors were undeterred. The petitions were appealed all the way to the Texas Supreme Court who ruled 7-0 that the signatures are indeed valid and ordered the Mayor to repeal the ordinance or put it up for a city vote. The Proposition 1 vote on November 3rd is the result of this eighteen month process.

Mayor Annise Parker’s attempt to subpoena sermons was completely outrageous. From the Wall Street Journal‘s report last year:

Pro bono attorneys representing Houston have demanded copies of sermons and other speeches given by five pastors and religious leaders who have spoken out against the ordinance, which bans racial and sexual orientation discrimination in city employment and contracting, housing and public accommodations.

A subpoena on Pastor Steve Riggle, senior pastor of Grace Community Church, asks for “all speeches, presentations, or sermons related to [the equal rights ordinance], the Petition, Mayor Annise Parker, homosexuality, or gender identity prepared by, delivered by, revised by, or approved by you or in your possession.”

Alliance Defending Freedom, a national conservative legal group, filed a motion on Monday in Harris County district court objecting to the records request on First Amendment grounds.

“City council members are supposed to be public servants, not ‘Big Brother’ overlords who will tolerate no dissent or challenge,” ADF senior legal counsel Erik Stanley said. “In this case, they have embarked upon a witch-hunt, and we are asking the court to put a stop to it.”

Happily, an overwhelming majority of Houston voters on Tuesday night told Annise Parker what she could do with her subpoenas. Before the vote, the Wall Street Journal reported:

A recent poll by a Houston television station, KPRC, found that 45% of Houstonians supported the measure, with 36% opposed, and the rest uncertain. Another poll by the Houston Association of Realtors found that 52% supported the ordinance, 37% opposed it and 10% were undecided.

And also from the WSJ:

Opposition signs proclaiming “No Men in Women’s Restrooms!” have popped up all over Houston, including in the Near Northside neighborhood, a largely Hispanic area near downtown, where the signs were sprinkled around an apartment complex on Monday, urging voters to defeat the proposal.

Houston-area readers correct me if I’m wrong, but it appears that the Vote No campaign focused heavily on the transgender part of the bill. I wonder if the measure would have passed had the LGB part stayed, but the T part had been dropped. In fact, Russell Berman of The Atlantic reports in the wake of the ballot measure’s defeat that that’s likely to have been the case:

Carlbom’s attitude might partly be due to the belief that even with a loss on Tuesday, a narrower anti-discrimination ordinance is likely to pass when a new mayor takes office next year. Opponents of Proposition 1 have said they would support a proposal that includes exemptions for bathrooms and locker rooms. “I would expect that type of ordinance to pass very quickly, with if not unanimous support then near-unanimous support in the city council,” Jones said.

With her term almost over, Parker refused to back off a fully-inclusive measure, but her successor might be more open to compromise. “She went for the maximum. She didn’t go for the 90 percent,” Jones said. “I think it reflects that HERO pushed just beyond the comfort zone of many Houstonians. And that small area beyond their comfort zone has been magnified 100-fold by the ‘no’ campaign.”

Despite what big business, the Democratic Party, and activists tell you, it is by no means a sign of hatred or insanity to not want to have to share the restroom with someone of the opposite sex.

Does Hillary Clinton support the Obama Education Department’s decision to force the nation’s public schools to allow transgender teens to use the locker room of their choice, or face a civil rights lawsuit? Somebody should ask her.

The Fragility of Historical Memory

How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy.

— Psalm 137, verses 4-6

A new Pew religious landscape survey is out today, and it shows that 1) overall, America is becoming a less religious country, and 2) the devout are in some ways becoming more devout, and the secularization is coming from the large number of Millennials who are losing their faith.

The clear conclusion is that Christianity in America is dying because its culture is dying. Do not forget sociologist Philip Rieff’s dictum: “The death of a culture begins when its normative institutions fail to communicate ideals in ways that remain inwardly compelling, first of all to the cultural elites themselves.” The faith is not being passed on to the young. This is measurable. So many of us Christians think that yeah, our kids may not be so observant, but they’ll come around in the end. The faith will always be here. I think this is extremely naive, because it does not take into account the fragility of historical memory in modernity.

In a sermon he gave earlier this week, on All Saints Day, the Baptist theologian Timothy George said:

In our culture today, saints have been replaced by celebrities. We know a lot about celebrities. Movie stars, sports figures, icons of politics and business. Celebrities have something about them that attract our attention: they are wealthy, they are glamorous, they are charismatic—they are celebrities! But saints are not celebrities. Saints are those whose lives, shaped by holiness, have been given freely in service for others. True, some of the great saints in the history of the church have become well known across time: St. Athanasius, St. Augustine, St. Francis. Yet most of the saints were not well-known in their own time. Some of them were little known at all. Perpetua was a mother pregnant with her child when she was called to witness to her faith in the arena at Carthage. Patrick, the apostle to the Irish, was a slave, taken away from his homeland to a foreign land. He declared, “I was like a rock stuck in mud until God by his grace lifted me up and gave me a new life.”

A little closer to our time is Jim Eliot, who, with his four friends, was speared to death in the jungles of Ecuador, where he had gone to share the message of Jesus Christ and his love. Or Maximilian Kolbe, a forty-seven year old Polish priest, number 16620 at Auschwitz, where he offered his life in exchange for another prisoner whom he hardly knew. In their own day, saints often received little reward, little applause. But now in glory they shine.

In my Benedict Option talk in Colorado Springs last weekend, I spoke of the importance today for us Christians to thicken our ties to the stories of the saints. We need to bring the narratives of the lives of these Christian heroes of ages past into our imaginations today, in part so we can know what we are to do by reflecting on what they did. We need to remember who they were so we can know who we are. Their stories are the stories of the Christian people. Christians who do not collectively remember their stories will lose their identity.

I have spoken of the Benedict Option as a project of remembering as resistance. The urban theorist Jane Jacobs was not a religious person, but she described our time as the beginning of a “Dark Age” in that it was characterized by mass forgetting. We have deliberately cut ourselves off from our own history; the past has no hold on us. We have maximized our own freedom by minimizing any narrative that tells us who we are and what we must do. We think of ourselves as self-created. There is no “Great Chain of Being” to the modern American, no order extrinsic to ourselves that we belong to. I think again of Rowan Williams’s remarks on Dostoevsky, which I highlighted in this recent post on the novel Laurus:

RW: Dostoevsky famously said: “If there’s no God, then everything is permitted.” It’s a view the west might consider more often. Dostoevsky’s not saying that if there’s no God then no one’s watching us and we can do what we like. He’s really asking: what’s the rationale for living this way and not otherwise? If there’s no God, then there’s no shape to our lives. Our behaviour needs to be in tune with something. If there’s no divine tune, how do you know where to go, what to do? To believe in God is not a business of rewards, but an ability to make sense of things.

[Interviewer]: And this ability can’t come from our experience of love and art, say?

RW: How do you see to it that one thousand flowers bloom and not one thousand weeds? The problem is one of the irreduceable divergence of moral ideals.

This is our condition. The contemporary Christian may look at this and thank God that he is not like those poor lost secularists, but he is not nearly as free from this trap as he thinks he is. In the many conversations I had over the weekend in Colorado Springs, it came up several times, in several ways, that Evangelical Christians are especially vulnerable to the shifting winds of culture, and tend to fall for faddishness. Evangelicals told me over and over that there is little or no consciousness of church history among their tribe. If any non-scholarly person thinks about the history of the Church at all, they said, it’s as if the Church took a big leap from the book of Acts to the Reformation.

Thing is, there may be some particularly Evangelical aspects to this phenomenon, but I don’t believe (like writing out 1,200 to 1,500 years of Church history), but I don’t believe American Catholics are much better in practice (the same may be true of US Orthodox, but I don’t have enough experience to say). This is not, obviously, because they are Catholics; Catholicism is a form of Christianity that in theory is profoundly shaped by history and maintaining the living continuity of the Church from Pentecost till today. This consciousness is barely present in contemporary American Catholicism, not because Catholics are Catholic, but because they are Americans, which is to say, they are moderns.

To be an American is to live in the present (“What do I want Now? What works for me Now?”). I would have said at one point that to be an American is to live in the future too, always looking ahead to the next new thing, but it seems to me that we don’t seriously plan for the future now, as in projecting ourselves imaginatively forward into the next generations, and allowing our present choices to be guided by a consideration of the effects they are likely to have on our children, their children, and their children’s children. To do so would limit the Self, and that is one thing we cannot have.

A reader of this blog, considering the long, much-updated post about my Colorado Springs experience, wrote to offer a thought about dissatisfied Evangelicals:

I find that most such folks hunger for a “traditional” Christianity but ONLY on their own terms. A “traditional” Christianity, but one which leaves them as the sole authority and judge over what that “tradition” actually is. For example, on such foundational things as church authority, worship, sacramental life (eucharist, particularly the major stumbling block of “closed communion,” confession, ordination (particularly women’s ordination, and which I believe will inevitably include homosexual as well), and such fundamental paradigm shifts such as what it means to be the “Body of Christ”, with respect to membership thereof (most of the members of these congregations move freely in and out of “traditional”, or on to the next fad, depending on their needs and desires of the moment).

The reader went on to express sympathy with Evangelicals who see value in expressions of traditional, liturgical Christianity, but also doubt that Evangelical dabbling in the trappings of Tradition will work without submission to the actual Tradition.

I think the reader is on to something, but I think this is very much a lesson that Catholics, Orthodox, and other Christians with deeper roots in liturgy and historical Christianity must ponder as well. I’ve mentioned many times before the testimony of my ex-Orthodox friends who say that all that rich liturgy and roots in the early church did nothing to hold them, because in their experience, it did not point them to a deeper relationship with God. It was all about worshiping the ethnos. And, there is a temptation easy to fall for within Orthodoxy, one identified by the late Russian Orthodox priest Alexander Schmemann, in his posthumously published Journals, which is a marvelous book:

Since the Orthodox world was and is inevitably and even radically changing, we have to recognize, as the first symptom of the crisis, a deep schizophrenia which has slowly penetrated the Orthodox mentality: life in an unreal, nonexisting world, firmly affirmed as real and existing. Orthodox consciousness did not notice the fall of Byzantium, Peter the Great’s reforms, the Revolution; it did not notice the revolution of the mind, of science, of lifestyles, forms of life. . . . In brief, it did not notice history.

The temptation is to mistake Traditionalism for Tradition. As theologian Jaroslav Pelikan memorably phrased it,

“Tradition is the living faith of the dead, traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. And, I suppose I should add, it is traditionalism that gives tradition such a bad name.”

Now, I know plenty of Catholics who have little if any regard for their faith’s traditions, and who treat their Catholicism like people who have cabinets full of beautiful china and drawers full of silver, but who choose to eat off of paper plates and with plastic forks — and who see no difference. Metaphorically speaking, they would rather eat McDonalds for Thanksgiving and say there’s no difference between that and the traditional turkey-and-dressing feast. It’s all ballast anyway, and besides, the only thing that matters is to eat what makes you happy. Most Catholics like this are not hostile to Catholic tradition, only indifferent to it. And then you have those Catholics, especially theologians, who are downright antagonistic towards it, and who want to destroy it (read this; it will unnerve you).

The point is, tradition — including liturgy and institutions — are necessary, but not sufficient to guarantee the passing-on of the faith. Last night, I finished reading the galleys of an excellent new book coming out in the spring, by the Evangelical writers David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons, in which they confront the hard challenges of living faithfully in post-Christian America. One of the things they point out, based on research data, is that among Evangelicals, the authority of Scripture is slipping.

Based on my purely anecdotal research (= talking with a diverse number of Evangelicals around the country), this is happening in part because Evangelical institutions are failing to teach Scripture as they once did. That, and, as an Evangelical who had been raised in a strict fundamentalist family told me last weekend, some of them are teaching it in a way that is so rigid and thoughtless (e.g., as a divine rulebook) that it cannot withstand the clash with culture outside its confines. The example this particular Evangelical used is the way many conservative churches within that tradition argue against homosexuality by citing decontextualized Bible verses, and fail to explore the deeper teaching in the Bible about sexuality, purpose, and human nature. If the only understanding a young Evangelical has about homosexuality is that ten or fifteen Bible verses condemn it, and that’s the extent of the Bible’s message about it, she will be susceptible to the Levitical sophistry of pro-gay antagonists, e.g., taking commandments from the book of Leviticus and saying, “If you take Leviticus seriously on homosexuality, then you are bound to take Leviticus seriously on not wearing wool and linen together. If you don’t take fashion advice from Leviticus, you shouldn’t take advice of sexual morality from it either.”

But I ramble. Lord, don’t I ramble.

Here’s a really interesting 1986 NYRB interview with Czeslaw Milosz. The interviewer (“G”) is Nathan Gardels. Excerpts below; emphases are all mine:

G: You’ve written about civic virtue in the West declining to such an extent that “the young generation ceases to view the state as its own, worthy of being served and defended even at the sacrifice of their lives.” Octavio Paz, the Mexican poet and essayist, says similar things. “The real evil of liberal capitalist societies is the predominant nihilism, not a nihilism which seeks the critical negation of established values, but a passive indifference to values.”

Where does this come from in the West?

M: The indifference, even the anti-American posture, which I have observed while teaching at Berkeley is very shocking. It is very hard to understand. Probably it means that still I come from a very traditional world as far as values are concerned. I have been witnessing in America the subversion of the ethic of the working class which was God, my country, my family.

As to the causes for all this, one can go back infinitely. I link it with a very profound transformation as far as religious imagination is concerned. There are some people who are optimistic about the state of religion today, but I am rather pessimistic. I consider that both believers and nonbelievers are in the same boat as far as the difficulty of translating religion into tangible images. Or maybe we can say that the transformation that is going on in religion reflects something extremely profound in the sense of nihilism. I am inclined to believe that only when profound shifts appear, for example a new science, will there be a basic change.

What do I mean?

At the present moment science is in the process of transition from the science of the nineteenth century to a new approach, in physics particularly. The whole society, as we observe in America, lives by the diluted “pure rationalism” of nineteenth-century science. What young people are taught in high school and the university is a naive picture of the world.

In this naive view, we live in a universe that is composed of eternal space and eternal time. Time extends without limits, moving in a linear way from the past to the future, infinitely. Functionally speaking, mankind is not that different from a virus or a bacteria. He is a speck in the vast universe.

Such a view corresponds to the kind of mass killing we’ve seen in this century. To kill a million or two million, or ten, what does it matter? Hitler, after all, was brought up on the vulgarized brochures of nineteenth-century science.

This is something completely different from a vision of the world before Copernicus, where man was of central importance. Probably the transformation I sense will restore in some way the anthropocentric vision of the universe.

These are processes, of course, that will take a long time.

G: In your writings, you link nihilism to memory. “The eye of the nihilist,” you quote Nietzsche writing in 1887, “is unfaithful to his memories; it allows them to drop, to lose their leaves.” In your Nobel lecture, you said that our planet is characterized “by the refusal to remember.”

M: If nihilism, as Nietzsche says, consists in the loss of memory, recovery of memory is a weapon against nihilism. There is probably no other country as full of historical memory as Poland, and somehow that memory provides a foundation for values. There is a link, a feeling of profound affinity and identity with past generations. With memory, classical virtues once again acquire value. In Polish poetry, memory goes back to Rome and Greece. There is a feeling of the continuity of European civilization. We find that a certain moral, even natural, law is inscribed in centuries of human civilization.

I feel that the greatest asset that my part of Europe received in the history of the twentieth century, the privilege of our being the avant-garde of inhumanity, is that the questions of true and false, good and evil, became operative again. Namely, good and evil, true and false, have been discovered not through philosophical discourse, but empirically, like the taste of bread.

In my opinion this is one of the secrets—maybe the main secret—of the mass participation of the Poles in religious rites today. One can say that this participation is purely political, that religion is popular because it marks political opposition of the nation to the state. But there is more than this. Nonbelievers and believers alike take part in the pilgrimages because they share the same notion of good and evil. And, the Church maintains, there is a convergence between believers and nonbelievers. Here is good, here is evil. This affirmation of basic values of good and evil brings people together.

G: Do we have a truthful way of thinking, of judging good or evil in the West?

M: Yes, but under the condition that intellectuals and writers do not insist on forcing nihilism in their descriptions of the world as the only valid image from the point of view of the literary establishment. Of course, every period has its fashions. To break away from fads is extremely difficult. Nihilistic presentation of the world is a fad today. And if there is an original talent, like Singer, who doesn’t care about it, he immediately grows in stature.

I feel great affinity with Singer because we both come from religious backgrounds, I from Roman Catholicism and he from Judaism. Constantly, we deal with similar metaphysical problems.

I have taught Dostoevsky for many years. And I have been fascinated by his prophetic insight into what was happening at that time in Europe and in Russia. He evinced a very deeply seated fear of the future, of the nihilism that would appear.

For me, the religious dimension is extremely important. I feel that everything depends on whether people are pious or not pious. Reverence toward being, which can be formulated in strictly religious terms or more general terms, that is the basic value. Piety protects us against nihilism.

But what happens when that very piety is infected with nihilism, in the Nietzschean sense that Milosz indicates? That is, what kind of condition do we enter when our religion embraces wholeheartedly the modern refusal to remember? Can a religious sense so construed possibly be an effective bulwark against nihilism?

I do not think it can.Piety that is based on Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is worse than no protection at all, because it lulls parents into thinking that they are giving their children what they need to carry on the tradition in an embattled age. In fact, they’re giving them armor made of paper and paste, and a sword forged from Play-doh.

Yet Christians who think they are doing better by their kids by enmeshing them in the aesthetic trappings of historical Christianity without committing to the spirit and substance of same are only embracing a more vivid and interesting illusion. If you go deep into the Pew numbers out today, you will see that on nearly every measure of piety, Evangelicals are much stronger than Catholics and Orthodox Christians. As someone who was once Catholic and is now Orthodox, I believe strongly that Catholics and Orthodox have ecclesiological advantages over Evangelicals when it comes to holding onto the faith in the long run. But the truth is, right now, Evangelicals are putting us to shame with their devotion.

For example, when asked what they look to most for guidance on questions of right and wrong, 52 percent of Evangelicals say “religion,” but only 22 percent of Catholics do, and 25 percent of Orthodox (the latter two favor “common sense,” by 57 and 52 percent, respectively). Unsurprisingly, I guess, only 28 percent of Evangelicals support same-sex marriage, while a majority of Catholics (57 percent) and Orthodox (54 percent) do. On abortion, 33 percent of Evangelicals say it should be mostly or entirely legal, while 48 percent of Catholics do, and a disgraceful 62 percent of Orthodox do. It would be nice to report that Americans with feet planted in the ancient church traditions were more likely to be historically orthodox on key moral issues addressed by the faith, but it’s not true. This is why I strongly believe that Evangelicals, Catholics, and Orthodox interested in the Benedict Option have to work it out together. Evangelicals have to learn how to embrace the Christian past, the “tangible images” of historical Christian culture, and the stability of historical forms — or the passionate conviction that keeps them relatively strong now will dissipate. Catholics and Orthodox are going to have to learn how to revive their inherited forms with much more passion and conviction, or they will wither.

I had never heard of the I.B. Singer novel The Penitent until I read it mentioned by Milosz. I read the Author’s Note on the Amazon.com page (yes, of course I ordered the book), and found a truth that is central to the Benedict Option. Singer says that there is no “final escape from the human dilemma, a permanent rescue for all time.

The powers that assail us are often cleverer than every one of our possible defenses; it is a battle which lasts from the cradle to the grave. All our devices are temporary, and valid only for one specific attack, not for the entire moral war. In this sense I feel that resistance and humility, faith and doubt, despair and hope can dwell in our spirit simultaneously. Actually, a total solution would void the greatest gift that God has bestowed upon mankind – free choice.”

This is the same truth Dostoevsky presents us in the parable of The Grand Inquisitor. There is no Benedict Option that can unfailingly defend us from nihilism, unless we refuse the divine gift of freedom, and choose slavery. Still, if we want to preserve our Christian freedom, and not be slaves to our passions, and to the present moment, we have no choice but to remember who we are, and pass on that memory effectively to the young. Teaching doctrine matters, but it’s not the most important thing. Creating a thick culture of Christianity is. Please do not fail to take seriously the words of church historian Robert Louis Wilken:

But Christ entered history as a community, a society, not simply as a message, and the form taken by the community’s life is Christ within society. The Church is a culture in its own right. Christ does not simply infiltrate a culture; Christ creates culture by forming another city, another sovereignty with its own social and political life.

… Material culture and with it art, calendar and with it ritual, grammar and with it language, particularly the language of the Bible—these are only three of many examples (monasticism would be another) that could be brought forth to exemplify the thick texture of Christian culture, the fullness of life in the community that is Christ’s form in the world.

Nothing is more needful today than the survival of Christian culture, because in recent generations this culture has become dangerously thin. At this moment in the Church’s history in this country (and in the West more generally) it is less urgent to convince the alternative culture in which we live of the truth of Christ than it is for the Church to tell itself its own story and to nurture its own life, the culture of the city of God, the Christian republic. This is not going to happen without a rebirth of moral and spiritual discipline and a resolute effort on the part of Christians to comprehend and to defend the remnants of Christian culture.

That is the reason for the Benedict Option. Resistance requires remembrance. Remembrance requires enculturation. The culture of modernity, of modern America, annihilates memory, sees memory as its enemy. If we forget Jerusalem in our exile in American Babylon, we will be assimilated and cease to exist. If we small-o orthodox Christians in the West do not lay claim to the past, and make it a living, vital part of our present, we are not going to have a future.

France: Not Paradise, Hélas

Pamela Druckerman, an American Francophile, moved to Paris twelve years ago. She idealized France, as many of us do (c’est moi!). But now she’s sad, as she tells readers of her NYT column:

I see now that France was never paradise. “Your alter country is all that your first was not,” writes the English author Julian Barnes, “commitment to it involves idealism, love, sentimentality and a certain selective vision.”

But France has also gotten worse. What once seemed like adorable grouchiness or “bleak chic” has morphed into something darker: a willingness to believe that people are walking here from Aleppo for free root canals; a sense that — despite being the world’s sixth-largest economy — France is powerless to help more.

At this point, the French even seem unhappy about how negative they’ve become. A positive approach to refugees would probably energize them. As it stands, France can no longer claim to have a universal message. These days, it’s just a flawed, ordinary country that mostly thinks for itself.

If you read the whole column, you’ll see that what disillusioned her is the fact that France does not want to open its door to these refugees. Is it really the case that she cannot see why a French person would not want to throw the doors of their country open to Muslims from the Third World? Did Charlie Hebdo not happen?

A French friend listening to me go on about how much I loved Paris told me that I should not forget that having rented an apartment in the 5th Arrondissement (the Left Bank), I was living in the Disneyland version of Paris. There I was surrounded by the culture, the civility, and everything people like me think of when we indulge in our romance with France. Adam Gopnik has written:

We are happy, above all, when we are absorbed, and we are absorbed when we are serious, and the secret of Paris, in the end, is that the idea of happiness it presents is always mingled, I do not always know how, with a feeling of seriousness.

That sense of serious happiness, of pleasure allied to education … this tincture of seriousness infiltrates our happiness, giving it dignity. In Paris, Americans achieve absorption without obvious accomplishment, a lovely and un-American emotion.

This is true, and glorious. It’s what makes Paris Paris, and what makes France France, at least in the eyes of Americans like me. But we should keep in mind a couple of things. First, France is no more paradise than any other country is paradise. Second, all the things we love about France didn’t just happen, and they aren’t going to be there forever without care and stewardship. It may be the case that France ought to take more refugees in. But I don’t understand why so many left-wing intellectuals have this idea that the liberalism that means so much to them is strong enough to withstand the presence of an alien people whose religious and cultural convictions are strongly illiberal.

My sense is that people like Pamela Druckerman delight in the experience of the fruits of French civilization without having to dirty their hands with the unpleasant things one has to do to cultivate the conditions that make those fruits possible. She should move to the banlieues and see how that affects her opinion about the failures of the French to be universalist humanitarians.

The Problem Is Not Racist Authority

Which of these two videos do you find more disturbing? The first one was taken recently at the Chicago Vocational Career Academy. Look:

The second one, which you have no doubt seen because it has received national media attention:

The sheriff’s deputy, Ben Fields, was later fired. From the NYT:

The deputy’s dismissal came after department officials conducted an internal review that, according to the sheriff, found that Deputy Fields had used a maneuver that violated the agency’s training and procedural standards. But Sheriff Lott also criticized the student, a sophomore, in harsh tones for “having started this whole incident with her actions.”

Deputy Fields, who could not be reached for comment, was called to an Algebra 1 class on Monday morning after, according to witnesses and law enforcement officials, the student refused her teacher’s requests to stop using her cellphone. After the student refused to leave the classroom, Deputy Fields forced her from her desk by flipping it before he pulled and threw her toward the front of the room.

Now the out-of-control Obama administration is conducting a civil rights investigation into the deputy’s actions, which could result in federal charges lodged against him. According to the sheriff who fired him, Fields has been in a long-term relationship with an African-American woman. Some kind of racist he is.

Two black TV personalities, Raven-Symoné and CNN’s Don Lemon, for criticizing the teenage girl. If my smart-aleck daughter had behaved that way in a classroom, and refused a deputy’s orders to get up and leave, I would buy him dinner for treating her that way.

Which of these two videos represents the greater threat to society, the behavior of the Chicago students, or the behavior of the South Carolina cop?

Even if one concedes that the cop overreacted, there’s no question in my mind which one is by far the worst. God help that poor Chicago teacher, Ms. Cox. You would have to be crazy to want to teach (“teach”) in a school (“school”) like that.

We can’t deny that the racist use of power by authority exists, and is a problem. When authority — the authority of law enforcement, of educational institutions, of religious institutions, and so forth — is abused by those who hold power, then they must be held accountable. The worse problem, though, as we see in the Chicago video (the fear in the eyes of the teacher is both heartbreaking and infuriating) is a total lack of respect for authority. Any authority.

UPDATE: A reader responds to this post in an e-mail, which I’ve ever so slightly altered with asterisks:

I hope your children are taken away from you very soon and placed with someone who does not condone assaulting them.

Christ, you’re an a**hole.

Dan Adams

Systems Administrator

Hawley, LLC

Thank you, Dan Adams, for showing your hand. I am pleased to know that you would have the state seize my children over my having expressed hypothetical sympathy for the cop. Left-wing tyrant that you and your ilk are.

UPDATE.2: Dan Adams writes back:

Left-Wing Tyrant checking in here. I am at a complete loss how you can claim to follow “The Prince of Peace” and yet condone this vicious, unprovoked *assault* on an orphaned black teenager.

The fact that you laughingly consider rewarding someone for throwing your own children to the ground in that manner is incredibly disturbing and frankly, unhinged. I stand by what I said and I advise you seek professional help before you ever do that to those who call you “Father”. How would your wife feel if she read this post?

And yes, if parents will not protect their own children from physical harm, the State should.

As an aside, people like you who claim Christ but condone child abuse are why I lost my faith.

And people like you are why even though I have big problems with organized conservatism, I have no faith at all in liberalism.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 508 followers