Rod Dreher's Blog, page 633

December 18, 2015

La Loi de l’Impossibilité Méritée

A French reader points out that the Law of Merited Impossibility (“It won’t happen, and when it does, you bigots will deserve it”) has come to France. From my translation of a story just published in Le Monde:

The former president of the Christian Democratic Party, Christine Boutin, was sentenced Friday, December 18, to pay a 5,000-euro fine for “public incitement to hatred or violence” against homosexuals for having said that “homosexuality is an abomination.”

The criminal court went beyond the request of the prosecutor, who had asked to end Oct. 1 hearing fine of 3,000 euros against her. Christine Boutin was also ordered to pay 2,000 euros in damages to each of the two [gay rights] associations, Mousse and Le Refuge, which were civil parties.

In an April 2014 interview with the magazine Charles, headlined “I am a sinner,” Christine Boutin said: “Homosexuality is an abomination. But not the person. Sin is never acceptable, but the sinner is always forgiven.”

“What we hear in your words is that homosexuals are an abomination,” the prosecutor summarized, stating that the prosecution had received 500 individual complaints after the statement.

Boutin’s lawyer asked for acquittal, arguing that his client was tried for “an opinion”. He then told the court:

“Your decision will have a huge impact on freedom of expression. If you follow the prosecution case, then we must grasp the Bible!”

Read the whole thing en français here.

So, it is now against the law to quote the Bible in France, if it offends the Homintern homosexuals. Where is the Cardinal Archbishop of Paris in all this? Has he said anything in Boutin’s defense? The French reader who sent me this news added:

Please note that Boutin made clear in her statement that it was homosexuality, not gay people, that she called “an abomination”. She also pointed that she was merely quoting from the Bible – All that to no avail. This is all the more shocking as it comes after the recent acquittal of the Femen for desecrating Notre-Dame de Paris. So don’t let them tell you that you’re hyperventilating and foster a “narrative of Christian oppression” – it is real and coming soon to America. Those who say it isn’t true either are deluded or secretly (?) support it.

Licio Gelli, Villain For the Ages

Licio Gelli, who has died aged 96, was a one-time fascist blackshirt and grandmaster of a secret masonic lodge at the centre of Italy’s biggest post-war political scandal; it centred around the collapse, in 1982, of the Banco Ambrosiano, and followed the death of the bank’s former president, Roberto Calvi, who was found in June 1982 hanging from Blackfriar’s Bridge in London.

More:

The Calvi and Banco Ambrosiano affair, however, was not the darkest page in the Gelli story.

In 1981, the year before the bank collapse, Gelli had made international headlines when a police raid on his office discovered a secret list of 1,000 prominent politicians, magistrates, journalists, businessmen (among them Italy’s future leader Silvio Berlusconi), policemen, the heads of all three of Italy’s secret services and some 40 senior military commanders, who were all members of P2. The discovery helped bring down the Christian Democrat government of Arnaldo Forlani.

When searching Gelli’s villa, police found a document headed “Plan for Democratic Rebirth”, which called for a consolidation of the media, suppression of trade unions, and the rewriting of the Italian Constitution. “The availability of sums not exceeding 30 to 40 billion lire would seem sufficient to allow carefully chosen men, acting in good faith, to conquer key positions necessary for overall control,” it read. A subsequent parliamentary commission said the aim of P2 had been “to exert anonymous and surreptitious control” of the political system.

Read the entire obituary. The Propaganda Due scandal wasn’t a case of an outlandish conspiracy theory; it really happened.

It is often a mystery to Americans why Europeans look on Freemasonry, which is so benign in the US (“Protestant voodoo” a friend of mine calls it) with such fear and suspicion. Well, this is why.

Meanwhile, Chinese Christians

Via The Browser, here’s a long interview with a Chinese pastor, about the persecution currently underway in China. “Pastor L” says “Right now, church communities in Zhejiang Province are experiencing a sense of defeat not seen over the last 30 years or so. The churches have underestimated the cruelty of the government. They thought the crackdown would come to an end after the Sanjiang Cathedral was demolished. But that has proven to be wishful thinking.” More excerpts:

[Pastor L:] But the cross removal campaign must be understood in the context of the Xi Jinping government’s tightening control of ideology. The authorities see Christianity as something outside their authoritarian sphere, and an imperialist legacy that identifies more with Western values. Indeed, it is one of five categories of citizens whom the government deems a threat to the security of the regime, along with rights lawyers, dissidents, Internet opinion leaders, and disadvantaged social groups.

The government sees Christianity as an independent political group. Indeed, its organization meets the definition of modern civil society, and is an autonomous society entity independent of the state. The Christian church is an intermediary for a self-governing, plural and open social space. The Holy Cross and the architecture of the church are expressions of the church’s physical presence in the public space, and symbols of social power.

Suspicious of religious organizations, the government does not tolerate the scope and influence of the church and regards it as a threat to its security. An internal meeting in Zhejiang Province in early 2014 required that “cadres in charge of ethnic and religious affairs must grasp the political matter behind the cross and resolutely resist infiltration.”

Note that well. More:

YC: While the cross demolition was taking place and over the following months, I regularly saw slogans like “sinicizing Christianity” and the “five entries and five transformations.” This month a purportedly international academic symposium was held in Beijing called “The Path to Sinicizing Christianity,” attended by representatives of the Party’s United Front Work Department, the State Administration for Religious Affairs, proxies like China Christian Council and the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, and a number of universities. What is the sinicization of Christianity? Is this is a new idea?

Pastor L: The official-led and directed campaign of “sinicizing Christianity” is in essence the politicization of Christianity—it’s forcing Christianity to “go communist,” or undergo a “socialist transformation.” The intent is to reform and remold Christianity into a Party-dominated tool that can be used in its service. A proponent of the “sinicization of Christianity” theory, official scholar Zhuo Xinping (卓新平), laid it out straight: “Christianity in China needs to emphasize sinicization politically; it must acknowledge and endorse our basic political system and its policies.”

At this conference in Beijing, “sinicizing Christianity” might mean different things for different parties, but the core, tacit presupposition of the meeting was that Christianity is a latent, potential political competitor with the Party. This already warps Christians’ own understanding of their identity as God’s people. It has absolutely nothing to do with what went on during the late Qing and Republican eras, in which grassroots Christians, as an organic part of their missionary work, experimented with and developed various forms of localizing and adapting Christian teachings to China.

When Nestorian Christianity entered China during the Tang dynasty, it integrated too much into Chinese culture, to the extent that the transmission of Christian teachings was stopped, in the end going away entirely. If Christianity neglects its ecumenical and theological tradition, all sorts of “abnormal” variations fused with Chinese folk traditions are apt to proliferate. The example of Hong Xiuquan’s “Taiping heavenly kingdom” is a familiar example. If the Church, on the other hand, overly attaches itself to state power, emphasizing nationalistic will, then secular powers are apt to sweep in and try to commandeer it. Nazi Germany’s instrumentalization of Lutheranism led to great tragedy. Many clerics in the Orthodox Church in Eastern Europe were later found to have been recruited as informants for the Communist Party, and when the archives were opened they were too ashamed to show their faces in public. In China, Christianity should draw a lesson from these cases and on no account let itself become a mistress of the Communist Party.

Are we American Christians bound to become Hauerwasian Anabaptists now, to avoid assimilation? I think so.

One more:

YC: Can you elaborate on how church communities have resisted these measures?

Pastor L: The “five entries and five transformations” go against Christian belief. Parishioners have ripped down the propaganda posters the government has put up in churches, they’ve criticized the project online, and churches that have compromised have been strongly urged not to and criticized by other churches. Some churches have refused to be subject to having their finances investigated. There was a house church that decided to chant scripture together if the government sent someone to stand at the altar and spread propaganda, not let them do it. If the officials managed to gain control, they’d rather give up than cooperate with government demands. Some churches have, in response, begun quoting from Jonathan Chao, the late North American pastor who founded China Ministries International, and promoted the “Three-Fold Vision” the “Chinese Gospel,” “nationalizing the church,” and “Christianizing the culture.”

YC: What do you mean by “rather give up?”

Pastor L: Abandon the whole church and meet in small groups at their own homes.

They are not going to give up. This is, in a way, a part of their Benedict Option.

Read the whole thing, and marvel at the faith of these brave people. We have a lot to learn from them, we Americans, especially on the Benedict Option front. Among the lessons I see:

1. The church is a mediating institution between the people and the state. The communist state cannot abide that. We Americans must ask ourselves if liberalism itself ultimately will not be able to abide mediating institutions. If so, what will we do? How will we prepare for that eventuality? Churches faithful to Scripture and tradition regarding homosexuality are already seen as a threat to civil order, and will increasingly be so. This is not going to get any better. And there will surely be other areas in years to come.

2. We US Christians must become much more aware of ourselves as “set apart” from post-Christian America. The general culture now is so far from Christian norms that if we continue to try to integrate ourselves with it, versus staying true to our theological traditions, we will lose our faith.

3. We had better have a plan for what happens when we lose our church buildings, and our institutions. What measures will we need to take to keep our communities thriving. If we find the courage not to bend to government or societal dictates, and, like the Chinese Christians, refuse to “give up,” what forms will that resistance take? What do we need to do now, in terms of forming ourselves internally, to be resistant?

Are there others? Talk to me. To be sure, I don’t expect a Chinese-style persecution here. But thinking about what we would do if it came helps prepare us for what we would do in a condition that is more likely, in my view: dhimmitude.

(The image above means ‘Jesus,’ and it’s from the wonderful Orthodox Christian book, Christ the Eternal Tao.)

UPDATE: I ought to have included the conclusion of the interview:

YC: Speaking of human shields, I recall this photo of the Xialing Church. This was Christmas Eve last year. Tell us, what happened?

Pastor L: In early December 2014, the Xialing Church was slated to be demolished by the authorities. Members guarded the church and foiled the government’s plans. Frustrated, officials ordered the demolition team to wreck the front steps. This is the church choir standing on the debris and singing; singing His glory amidst the ruins—this epitomizes the spirit of Chinese Christians right now. Christmas is again approaching, and particularly befitting to churches in Wenzhou, in Zhejiang province, or across China for that matter, is the ancient song in praise of God: “Glory to God in the highest, and on the earth peace among men with whom he is well pleased.” (Luke 2:14)

‘The Narrative of Christian Oppression’ (Updated)

A Christian professor at a secular university has had it with the accounts I publish from Christians in higher education. This is a great letter:

I’ve wanted to write to you for some time about your coverage of higher education, but your latest post is the last straw. I want to say two things. One, this student who wrote to you would not be rational—assuming he describes events accurately and completely—in leaving academia on the basis of those events. Two, the way that you write about these things and the stories you publish are destructive. They are not helping the situation of Christian academics—they are making things worse. I say this not out of any hostility to you or your blog. I’ve been reading your blog for years. I agree with you about almost everything. My complaint is not about your point of view; it is about how you are expressing it.

I have been in the academic world for almost twenty years; many of those as a graduate student, and many as a teacher and researcher. I have always studied and taught at secular institutions. In the beginning, it was by default; I was secular, when I started out. I converted to Christianity shortly after I started teaching, and from then on it was a choice that I made–more than once–to stay and teach in secular schools. I have witnessed many incidents that fit well into your narrative, ones that you would quickly publish as evidence of the complete corruption of the academic world and for the necessity of retreating Benedict-style into the wilderness. And yet these incidents are not the whole story.

Take the student’s story that you published today. Is this a story about the unbearable climate for Christian academics? In a way, yes. But there’s another perspective. In a way, there is no such thing as a ‘climate’. There are only individual human beings. This professor is a human being– a bad professor, if he or she is as described. Why? For one thing, he has a bad interpretation of the Annunciation. He is (I take it) assuming that the story has its source in pagan myths about the gods raping mortals and producing offspring. But it is much more plausible to think that the gospel writers, insofar as they have stories like this in mind, are undermining them, are arguing that this God, the true god, does not deal with mortals in this way. The gospels emphasize consent. The fathers of the Church emphasize consent. Nothing could be more important (in a certain respect) to Catholic and Orthodox theology than the consent of Mary. It is a fallacy to assume that when an author has a source (assuming the myths are a source here) he or she uses it uncritically. Given that—could the graduate students have brought an alternate interpretation to the professor directly? Would he have engaged in the conversation? Will he engage in it now? Mind you, he might not be convinced, but he should engage. If not, he is a bad professor and a bad thinker, too wedded to his own views to analyze them or defend them. The student could find a secular professor (or more than one) who would find such behavior objectionable—it violates common-sense standards. If he can’t find a sympathetic person in his department, he should transfer out of that program, because it is not one that has any serious standards.

The fact that the chair of the department held a meeting with the TAs and the professor shows that the chair believed that something may have gone wrong. That is a sign that the ‘climate’ is not quite as the letter-writer sees it. Now, the chair made a mistake in handling the situation this way. That’s because everyone knows that grad students are cowards. They will not state their honest opinion in front of the professor, because, as the letter writer notes, they are afraid that their careers will be damaged. The chair should have talked to students privately and formed his or her own judgment. The letter-writer, or the woman who was badly treated, should now talk to the chair privately about how they think the situation was handled. Perhaps this conversation will not go well. Perhaps the chair is really deeply unsympathetic to the students and doesn’t care about upholding standards for reasonable disagreement. In that case, again, find a different department. In terms of the professor’s outrageous remark to the student to STFU: how has the student complained about it? As about the professor’s refusal to engage with disagreement (one issue) or as about inappropriate or abusive behavior (another issue)? Both separately can be raised both with the professor and with the chair.

Notice that none of these possible conversations are about the treatment of Christianity or Christian students. Rather, they are about 1) the meaning of the Annunciation and the correct representation of Christian theology 2) appropriate ways of responding to disagreement from students 3) effective ways of handling conflict between professors and graduate TAs 4) inappropriate or abusive behavior.

What I suspect has happened instead is that the letter-writer has viewed these events through the lens of the oppression of Christian academics—the Narrative of Christian Oppression. That has led him to view the situation as hopeless and to fail to try to communicate with the human beings in question in a way that might resolve the difficulties. Now, I know nothing about the outcomes of these possible conversations. Perhaps they will end with the professor or the chair saying “You, Christian, do not belong in this department”, or the equivalent. If so, the Christian student can depart in peace, shaking the dust from his feet, knowing that he has reaching the limits of what he can reasonably do. But perhaps they will end quite differently. Perhaps they will not fit neatly into the narrative at all. The student has neatly skated over the evidence that his department is not as bad as he thinks: the fact that the chair held a meeting about these events, and the fact that they accepted him into the program, even though he interpreted literature in his writing sample. Some member or members of the department read that writing sample and thought it was good: that is a fact.

The way to survive in these programs is to cling to common ground. Cling to standards, cling to the love of literature (or history or whatever it is). Cling to the work that you share as a project with your non-believing colleagues and teachers. Seek out people who value something in common with you, especially if they are not Christian. Form friendships. Work together on the basis of those common values. A standard for behavior or a standard for good thinking is not a static thing. It is valued in the breach as well as in the observance. Speak to your teachers and fellow-students as if they, too, can recognize the breach and can respond to it. Accept their response if they acknowledge the breach, even if the result is not what you wanted. Forbear some injuries. Fight when necessary. Make the choice to stay, make it repeatedly, because of your love of the subject and because you can adequately pursue what you love.

When you are in an environment where there is no common ground, where there is nothing you value in common with the others—when you know that not because you read too many blogs but because you have met your teachers and fellow-students eyeball-to-eyeball and forced them to clarify what they accept and what they reject—then it is time to leave. Or you can choose to leave because for you the pain of the struggle outweighs the joy of the work. But make no mistake: that’s your calculation, and it’s your choice.

Having these conversations and forming these relationships is difficult. It is awkward. The continual testing of the difficult teacher, the difficult department, is tedious and fraught with anxiety. Engagement involves taking a risk, the risk that the authority figures in question will turn against you, that you may not be able to succeed in the way you set out to do. But look—if you are thinking of leaving the profession, what difference does it make? If the climate is that bad, you have nothing to lose by engaging your teachers and colleagues. You have nothing to lose by speaking your mind. Nothing to lose, that is, but the sense of your superiority to them—the sense of superiority which is the worst temptation of Christian academics like myself.

Not only that, but there are always other options beyond leaving the profession: switching advisors, switching programs, switching fields. Part of the human perspective on these questions involves taking in the massive differences between individual teachers, programs, and fields. For instance, I suspect English is the worst field for this sort of thing. History, philosophy, classics, the sciences are generally better. You very often have the option to switch. But you won’t think about those options if you are enchanted by the Narrative of Christian Oppression. You will flee at the first difficulty, just as this student seems ready to do, because you will think from reading Rod Dreher that the whole university system has gone to hell and there’s no hope for any of it.

I teach now at the secular liberal arts college where I was an undergraduate. It has never been a place where religion was marginalized—never. But over the past few years we get fewer and fewer Christian students. The student body is increasingly secular. I wonder if that is because the Christian students and their parents read this blog (and others like it) and think that their only hope is in a Christian college. This is a terrible shame for two reasons. For one, it is a terrible loss to colleges like this one. I would never have become a Christian if I had not forged friendships with Christian students at the secular institutions I attended. Further, how will our tradition of open conversation and real community across differences hold up if there are fewer and fewer religious students and teachers?

But there is a second reason that the abandonment of secular institutions by Christians is a shame, and I will be blunt. Contemporary Christians—taken as a group—do not have the intellectual heft of their secular counterparts. The best scholarship, the highest quality thinking, still goes on at secular institutions. To go to a Christian institution involves—by and large–an intellectual compromise. (Notre Dame is one exception, but you could argue that that is because it is such a secularized place). The Narrative of Christian Oppression is partly to blame. Rather than thinking about history, or philosophy, or literature, or any of the disciplines, Christian academics have a tendency to get preoccupied with their correctness, with their superiority to their secular counterparts. Insofar as this infects the Christian curricula and the culture at these institutions, their precious focus on their disciplines themselves and the excellence it makes possible are lost. Someday secular academia really may go to hell in a handbasket, and your Benedict Option will be necessary. But I sure hope that in the meantime Christian academics will carry away as many Egyptian treasures as they can. What they’d take now sure wouldn’t count for much.

I’ve had my own struggles. I too am continually tempted by the prospect of my own superiority. I’ve always tried to engage with the secular world. I have felt sometimes as if the attempt to engage was too draining to be worth it. It certainly isn’t for everyone. Members of oppressed minorities, whether they are historically oppressed races, women in male-dominated fields, or Christians in secular schools, they have to take on more strain. It is harder for us. That strain can make you bitter, or it can be taken up with that cross we are all supposed to take up. It can, indeed, be a heroic, beautiful, joyful struggle, just as anything worthwhile is, no matter how small or invisible or seemingly ineffectual.

If you print this, please don’t print my name, not because I’m afraid of repercussions, but because I don’t want the image of a culture warrior with my students. At my school we don’t talk about our religious or political identities in class. That’s because we create real “safe spaces” where students can actually say what they think without any fear of judgment. My views aren’t secret—I share them with students and colleagues privately—but I do not publicize or flaunt them out of respect for the openness of those conversations.

The professor identified herself to me privately, and her institution. I’m really grateful to her for having written. I don’t know about the climate in higher education aside from what friends within it and readers tell me. More information is better, I think. So, thanks.

UPDATE: Here is an e-mail from the professor who wrote the above essay:

I am concerned that I seemed to be judging the grad student harshly. That was not my intention. I am deeply sympathetic with the grad student and with all Christians trying to live their faith in a secular environment. The approach to conflict that I suggested of conversation, engagement, and civil confrontation is very rarely seen in academia. If the grad student didn’t try it, or didn’t try it hard enough—and that is just my guess based on what he or she said—that isn’t surprising or particularly blameworthy. I know about the power of the Narrative of Christian Oppression, because I’ve fallen prey to it many times, and it has discouraged me deeply and has fed my impulses to leave the profession. But I know, for myself, that to give into that impulse would be a mistake, and I think it is a tragedy if others give into it prematurely or hastily or without looking at their circumstances with a cold eye to the possible.

I didn’t call anyone a snowflake and I didn’t tell anyone to suck it up. Many of these events are real injustices and real outrages. Injustice of this kind can shake you down to your elements. My intention was to encourage: it is worth it, it is worth it—and to give some practical suggestions as to how to move forward. But it was not to deny reality. I wouldn’t read Rod’s blog if I didn’t think he was tracking something real. Academia is in a steep decline. Many corners of it are toxic. Sometimes the approach I suggested will result in rejection and failure. It is very difficult to find a place where you can do your work and thrive. It took me a long time to find mine, and I know well enough there are few like it and that they face a growing legion of challenges. Probably I have been too hard on Rod too. The fact is that journalism might help you track the bigger picture of the state of our institutions. Still, the stories that are most newsworthy aren’t the most representative. That’s why reading journalism can be so destructive for living your daily life. It really can blind you to who is standing in front of you and what is possible with them. It feeds fear and despair. Fear and despair are poison. A touch of ‘damn the torpedoes’ is essential to survive and be happy in academia.

As for the relative quality of Christian vs secular institutions, I meant no offense. Obviously there is widespread stupidity and intellectual dishonesty at secular schools. That was, in fact, a premise of my letter. Still, I spoke too loosely. There are legions of wonderful Christian scholars, teachers, and institutions. In many cases a Christian institution may be preferable. My point was simply that the Narrative of Christian Oppression can discourage attending secular schools in cases when they are, in fact, the better option; that, in many cases, a secular school is a better place in terms of intellectual excellence; and that secular schools can nurture faith for believers and non-believers. My concern is partly too that if we were to all secede, Benedict Option style, we would have a pale and paltry sort of academy, taken as a whole, that the loss of intellectual excellence at this point would be a steep price to pay for independence. I could be wrong about that, but it’s surely worth asking the question of what the Benedict Academy would really look like.

Retreat is not the only response to decline. A firefighter can keep pulling children out of burning buildings even as his resources decline, his equipment decays, and bureaucracy strangles common sense. It’s still worthwhile, down to the last child, if he can stay focused on what matters.

The grad student who wrote the original complaint responds to the professor’s first letter (above):

I understand many of your commenters’ misgivings about the story, including the professor for whom my letter was the “last straw.” I could have elaborated several other incidents in which I was directly involved or witnessed at first-hand, but the one I related seems best to exemplify how bad the situation can be even at “safe” schools. I do recognize that it is a solitary incident, not a pattern of abuse, and one that I didn’t experience directly. These elements of my story are impeachable, obviously. I’m glad that many of your readers expressed their understandable dubeity regarding the story. I certainly don’t begrudge them that.

I would note, though, that incidents of this magnitude don’t happen everyday, of course, but varieties of them do happen everywhere and to a lesser and more insidious extent. What concerns me most isn’t the Christian vs. non-Christian dynamic here; rather, it’s the issue of narratives that have power (and the institutional wherewithal to enforce that power) vs. the narratives that don’t. Perhaps it was irresponsible of me to send along that particular story, and I apologize if it was. Perhaps I unwittingly fanned the flames of the “Narrative of Christian Oppression.” In any event, your readers have made of it what they will. It was merely my small contribution to the discussion.

I would also note, since some readers seemed to mistake me, that I’m not overly bothered by the ham-fisted, “edgy” misreading of the Annunciation narrative. I mean, goodness, we’re in the season in which the astonishingly radical Christian belief in the Incarnation is repackaged and commodified into something that is neither threatening nor even remarkable to polite consumerist sensibilities. This pervasive commercialization of Our Lord’s Nativity disturbs me way more than some prof spouting eisegetical garbage to a room full of undergrads, most of whom were probably paying closer attention to Facebook than to said lecture. The problem has more to do with expectation of TAs’ corporate submission to that secularist reading, which seems much more sinister and problematic.

And please don’t get me wrong: as I noted, [my university] isn’t the worst place in academia. Far, far from it. … Relatively speaking, it is less hostile to Christians and conservatives than elsewhere. I was blessed with a few professors and a handful of classes that were dedicated to true humanistic inquiry rather than proliferating theoretical mumbo-jumbo. “Relatively speaking” is the operative phrase, though; the department is huge, so one is bound to have a handful of professors who don’t fit the mold. And the sympathetic ones are all, not coincidentally, older professors, in part because they have the professional luxury not to put their tenure or promotion on the line.

But younger professors don’t have the same prerogative to step out of line. That’s the case in any hierarchical organization, of course, but the standards–one would think–ought to be higher in a profession that prides itself on fostering the virtue of boundless inquiry. When one looks at what is published in the field, one realizes that the gatekeepers to publication (and thus to professional success) have very little interest in publishing anything that strays beyond a certain, narrowly-construed set of ideological commitments. Prof. Lisa Ruddick’s article in The Point reinforces this point. Some of this is a matter of generational perspective. Having senior professors tell grad students and junior faculty that it’s not really as bad as we’re making it out to be strikes me as a bit patronizing, but maybe that’s just me? I’ll admit that we grad students (and I, the chief of sinners) need to do less extrapolating from, and hand-wringing over, our own limited experiences in the academy.

Maybe I’ve also fallen prey to Special Snowflake Syndrome and am thus willing to internalize and personalize events that are ultimately impersonal. I entertain that possibility. Many of the comments and letters in response to my story were useful in helping me to recognize that I may need to moderate my perspective somewhat. I do worry that some of my thinking in this regard merely serves to reinforce the ghetto-ization of Christian academics. (But then one wonders if the ghetto doesn’t already exist and its boundaries are simply beginning to become apparent to us?) In any case, there are enough other structural problems in academia apart from this issue that have also contributed to my decision to get out (for the moment, at least). At least half of my PhD cohort has left academia for reasons having nothing to do with any of these issues. So it goes. It’s a weird place to be.

My friend and TAC contributor Alan Jacobs, a Baylor University literature professor (who used to teach at Wheaton) addresses this controversy here. In this excerpt, he challenges the Fed-Up Christian Professor’s claim (in the original essay above) that secular universities on balance offer a better education than Christian ones (“To go to a Christian institution involves—by and large–an intellectual compromise.”). Here’s Alan:

I believe the kind of education students receive in the Honors College at Baylor, and at Wheaton, is in most respects far superior to what they would receive at secular schools of greater academic reputation and social prestige. Indeed, in my years at Wheaton I often heard comments to this effect from visitors. I think for instance of a professor at one of America’s top ten universities who said to me, after spending some time with one of my classes, “Your students are better informed and ask more incisive questions than mine do.”

I could adduce more examples, and explore more comparisons, but let me conclude with this: If this professor’s commendation of Wheaton’s students has at least somevalidity, how might we account for this state of affairs? I would point to three factors:

1) At Christian colleges, students and faculty alike tend to think of learning as a project in which the whole person is involved. Information is not typically separated from knowledge, nor knowledge from wisdom. The quest for education is less performative, more earnest than at many secular institutions. People are more likely to think and speak of education as something that leads to eudaimonia, flourishing.

2) A closely related point: Christian institutions tend to think quite consciously that their task involves Bildung, the formation of young people’s characters as well as their minds. So in hiring and retention they place a greater emphasis on teaching and mentoring than is common in secular institutions. (There are exceptions, of course, but even the most student-centered secular institutions cannot, because of their intrinsic pluralism, specify what good personal formation looks like.)

3) Perhaps the most important feature: Christian teachers and students alike can never forget that their views are not widely shared in the culture as a whole. We read a great many books written by people who don’t believe what we believe; we are always aware of being different. This is a tremendous boon to true learning, because it discourages people from deploying rote pieties as a substitute for genuine thought. No Christian student or professor can ever forget the possibility of alternative beliefs or unbeliefs. Most students who graduate from Christian colleges have a sharp, clear awareness of alternative ways of being in the world; yet students at secular universities can go from their first undergraduate year all the way to a PhD without ever having a serious encounter with religious thought and experience — with any view of the world other than that of their own social class.

Read Alan’s entire piece here.

And Robert Oscar Lopez, a tenured Christian academic who has been put through professional hell because of his stated views on homosexuality, says in the comments section:

I have to break ranks and offer a critical response to this anonymous letter. I think the unnamed author is unfair and condescending. She admits she doesn’t really know the particulars of the story she’s responding to but she presumes that the coping mechanisms that have served her in her apparently fortunate and comfortable situation will work for everyone. Given that she does not reveal her name, which all but discredits her in my view (if she can’t deal with possible resistance to her ideas from other Christians on a blog, why on earth do I think she knows how to deal with serious anti-Christian bias on a hostile campus?) I think her feedback with its somewhat overheated reaction to what she sees as Christian whining is frivolous. I have been in the academy for 20 years, I got tenure, I made nice-nice with everyone and tried going to lunch with colleagues, but in the end, when they came for the Christians, they came for me, and I had to sift through the wreckage. The person who wrote this anonymous letter sounds like the whispering chorus of frightened, cowardly conservatives who have crossed my path over two decades, always hiding in their bunkers and wanting so badly for leftists to really like them and think they’re not like those smelly ones, still “clinging,” as the author puts it, to a mythical meritocracy as if the leftists who have demonstrably destroyed the academy are reasonable people to be persuaded by someone with the right rhetorical gifts. People like Carol Swain, John McAdams and me are under fire–serious, vicious, unyielding attack–and we need bold Christians to defend our faith in the public square, not timid little squirrels offering stale chestnuts under pseudonyms. I am sorry to be so rude, but her letter is rather dismissive and inconsiderate in its own way so I don’t feel that bad.

(This has been such a great discussion!)

‘The Narrative of Christian Oppression’

A Christian professor at a secular university has had it with the accounts I publish from Christians in higher education. This is a great letter:

I’ve wanted to write to you for some time about your coverage of higher education, but your latest post is the last straw. I want to say two things. One, this student who wrote to you would not be rational—assuming he describes events accurately and completely—in leaving academia on the basis of those events. Two, the way that you write about these things and the stories you publish are destructive. They are not helping the situation of Christian academics—they are making things worse. I say this not out of any hostility to you or your blog. I’ve been reading your blog for years. I agree with you about almost everything. My complaint is not about your point of view; it is about how you are expressing it.

I have been in the academic world for almost twenty years; many of those as a graduate student, and many as a teacher and researcher. I have always studied and taught at secular institutions. In the beginning, it was by default; I was secular, when I started out. I converted to Christianity shortly after I started teaching, and from then on it was a choice that I made–more than once–to stay and teach in secular schools. I have witnessed many incidents that fit well into your narrative, ones that you would quickly publish as evidence of the complete corruption of the academic world and for the necessity of retreating Benedict-style into the wilderness. And yet these incidents are not the whole story.

Take the student’s story that you published today. Is this a story about the unbearable climate for Christian academics? In a way, yes. But there’s another perspective. In a way, there is no such thing as a ‘climate’. There are only individual human beings. This professor is a human being– a bad professor, if he or she is as described. Why? For one thing, he has a bad interpretation of the Annunciation. He is (I take it) assuming that the story has its source in pagan myths about the gods raping mortals and producing offspring. But it is much more plausible to think that the gospel writers, insofar as they have stories like this in mind, are undermining them, are arguing that this God, the true god, does not deal with mortals in this way. The gospels emphasize consent. The fathers of the Church emphasize consent. Nothing could be more important (in a certain respect) to Catholic and Orthodox theology than the consent of Mary. It is a fallacy to assume that when an author has a source (assuming the myths are a source here) he or she uses it uncritically. Given that—could the graduate students have brought an alternate interpretation to the professor directly? Would he have engaged in the conversation? Will he engage in it now? Mind you, he might not be convinced, but he should engage. If not, he is a bad professor and a bad thinker, too wedded to his own views to analyze them or defend them. The student could find a secular professor (or more than one) who would find such behavior objectionable—it violates common-sense standards. If he can’t find a sympathetic person in his department, he should transfer out of that program, because it is not one that has any serious standards.

The fact that the chair of the department held a meeting with the TAs and the professor shows that the chair believed that something may have gone wrong. That is a sign that the ‘climate’ is not quite as the letter-writer sees it. Now, the chair made a mistake in handling the situation this way. That’s because everyone knows that grad students are cowards. They will not state their honest opinion in front of the professor, because, as the letter writer notes, they are afraid that their careers will be damaged. The chair should have talked to students privately and formed his or her own judgment. The letter-writer, or the woman who was badly treated, should now talk to the chair privately about how they think the situation was handled. Perhaps this conversation will not go well. Perhaps the chair is really deeply unsympathetic to the students and doesn’t care about upholding standards for reasonable disagreement. In that case, again, find a different department. In terms of the professor’s outrageous remark to the student to STFU: how has the student complained about it? As about the professor’s refusal to engage with disagreement (one issue) or as about inappropriate or abusive behavior (another issue)? Both separately can be raised both with the professor and with the chair.

Notice that none of these possible conversations are about the treatment of Christianity or Christian students. Rather, they are about 1) the meaning of the Annunciation and the correct representation of Christian theology 2) appropriate ways of responding to disagreement from students 3) effective ways of handling conflict between professors and graduate TAs 4) inappropriate or abusive behavior.

What I suspect has happened instead is that the letter-writer has viewed these events through the lens of the oppression of Christian academics—the Narrative of Christian Oppression. That has led him to view the situation as hopeless and to fail to try to communicate with the human beings in question in a way that might resolve the difficulties. Now, I know nothing about the outcomes of these possible conversations. Perhaps they will end with the professor or the chair saying “You, Christian, do not belong in this department”, or the equivalent. If so, the Christian student can depart in peace, shaking the dust from his feet, knowing that he has reaching the limits of what he can reasonably do. But perhaps they will end quite differently. Perhaps they will not fit neatly into the narrative at all. The student has neatly skated over the evidence that his department is not as bad as he thinks: the fact that the chair held a meeting about these events, and the fact that they accepted him into the program, even though he interpreted literature in his writing sample. Some member or members of the department read that writing sample and thought it was good: that is a fact.

The way to survive in these programs is to cling to common ground. Cling to standards, cling to the love of literature (or history or whatever it is). Cling to the work that you share as a project with your non-believing colleagues and teachers. Seek out people who value something in common with you, especially if they are not Christian. Form friendships. Work together on the basis of those common values. A standard for behavior or a standard for good thinking is not a static thing. It is valued in the breach as well as in the observance. Speak to your teachers and fellow-students as if they, too, can recognize the breach and can respond to it. Accept their response if they acknowledge the breach, even if the result is not what you wanted. Forbear some injuries. Fight when necessary. Make the choice to stay, make it repeatedly, because of your love of the subject and because you can adequately pursue what you love.

When you are in an environment where there is no common ground, where there is nothing you value in common with the others—when you know that not because you read too many blogs but because you have met your teachers and fellow-students eyeball-to-eyeball and forced them to clarify what they accept and what they reject—then it is time to leave. Or you can choose to leave because for you the pain of the struggle outweighs the joy of the work. But make no mistake: that’s your calculation, and it’s your choice.

Having these conversations and forming these relationships is difficult. It is awkward. The continual testing of the difficult teacher, the difficult department, is tedious and fraught with anxiety. Engagement involves taking a risk, the risk that the authority figures in question will turn against you, that you may not be able to succeed in the way you set out to do. But look—if you are thinking of leaving the profession, what difference does it make? If the climate is that bad, you have nothing to lose by engaging your teachers and colleagues. You have nothing to lose by speaking your mind. Nothing to lose, that is, but the sense of your superiority to them—the sense of superiority which is the worst temptation of Christian academics like myself.

Not only that, but there are always other options beyond leaving the profession: switching advisors, switching programs, switching fields. Part of the human perspective on these questions involves taking in the massive differences between individual teachers, programs, and fields. For instance, I suspect English is the worst field for this sort of thing. History, philosophy, classics, the sciences are generally better. You very often have the option to switch. But you won’t think about those options if you are enchanted by the Narrative of Christian Oppression. You will flee at the first difficulty, just as this student seems ready to do, because you will think from reading Rod Dreher that the whole university system has gone to hell and there’s no hope for any of it.

I teach now at the secular liberal arts college where I was an undergraduate. It has never been a place where religion was marginalized—never. But over the past few years we get fewer and fewer Christian students. The student body is increasingly secular. I wonder if that is because the Christian students and their parents read this blog (and others like it) and think that their only hope is in a Christian college. This is a terrible shame for two reasons. For one, it is a terrible loss to colleges like this one. I would never have become a Christian if I had not forged friendships with Christian students at the secular institutions I attended. Further, how will our tradition of open conversation and real community across differences hold up if there are fewer and fewer religious students and teachers?

But there is a second reason that the abandonment of secular institutions by Christians is a shame, and I will be blunt. Contemporary Christians—taken as a group—do not have the intellectual heft of their secular counterparts. The best scholarship, the highest quality thinking, still goes on at secular institutions. To go to a Christian institution involves—by and large–an intellectual compromise. (Notre Dame is one exception, but you could argue that that is because it is such a secularized place). The Narrative of Christian Oppression is partly to blame. Rather than thinking about history, or philosophy, or literature, or any of the disciplines, Christian academics have a tendency to get preoccupied with their correctness, with their superiority to their secular counterparts. Insofar as this infects the Christian curricula and the culture at these institutions, their precious focus on their disciplines themselves and the excellence it makes possible are lost. Someday secular academia really may go to hell in a handbasket, and your Benedict Option will be necessary. But I sure hope that in the meantime Christian academics will carry away as many Egyptian treasures as they can. What they’d take now sure wouldn’t count for much.

I’ve had my own struggles. I too am continually tempted by the prospect of my own superiority. I’ve always tried to engage with the secular world. I have felt sometimes as if the attempt to engage was too draining to be worth it. It certainly isn’t for everyone. Members of oppressed minorities, whether they are historically oppressed races, women in male-dominated fields, or Christians in secular schools, they have to take on more strain. It is harder for us. That strain can make you bitter, or it can be taken up with that cross we are all supposed to take up. It can, indeed, be a heroic, beautiful, joyful struggle, just as anything worthwhile is, no matter how small or invisible or seemingly ineffectual.

If you print this, please don’t print my name, not because I’m afraid of repercussions, but because I don’t want the image of a culture warrior with my students. At my school we don’t talk about our religious or political identities in class. That’s because we create real “safe spaces” where students can actually say what they think without any fear of judgment. My views aren’t secret—I share them with students and colleagues privately—but I do not publicize or flaunt them out of respect for the openness of those conversations.

The professor identified herself to me privately, and her institution. I’m really grateful to her for having written. I don’t know about the climate in higher education aside from what friends within it and readers tell me. More information is better, I think. So, thanks.

December 17, 2015

Court: Catholic School Must Hire Gay Man

Well, well, well, that didn’t take long:

A state court in Massachusetts has ruled that a Catholic preparatory school violated the state’s antidiscrimination law when it rescinded a job offer to a man because he was married to another man.

Matthew Barrett had accepted a job as Food Service Director at the Fontbonne Academy, a Catholic girls school. On his employment forms, he listed his husband as his emergency contact — a move that led the school to rescind the job offer.

On Wednesday, Superior Court Associate Justice Douglas Wilkins ruled that Fontbonne discriminated against Barrett based on sexual orientation and rejected the school’s arguments as to why it should be exempted from the state law or otherwise not subject to its employment discrimination ban.

Barrett’s lawyers from Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders praised the judge’s ruling as “the first of its kind in the country.”

And not likely the last, unless it’s overturned on appeal. You really should read the whole thing to grasp the court’s reasoning.

The Law of Merited Impossibility: “It won’t happen, and when it does, you bigots will deserve it.”

Christianity In the Brave New World

Michael Hanby, who teaches philosophy of science at Catholic University’s John Paul II Institute, recently gave a powerful lecture in Philadelphia, at the invitation of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese there. It speaks deeply to the reason for the Benedict Option, perhaps the most fundamental reason for it. I have a written copy of the lecture, but Michael has asked me not to publish it here, because he is reworking it as a magazine essay. However, he has given me permission to summarize it, and to quote selectively from it.

Hanby begins by assuring his audience that his is a lecture about hope. It’s important to keep that in mind, because what he goes on to say is pretty grim. Excerpt:

It should be obvious to anyone with eyes to see and ears to hear that we are living through some sort of social revolution, though it is less than obvious just what sort of revolution this is. Nevertheless the signs of change are everywhere, extending widely across different spheres of life which seem, at first glance, to have little to do with each other. Ubiquitous electronic devices have radically reshaped the way we speak and think—there is some evidence that they may even changing our neuro- physiology—and they have just as profoundly reshaped personal and public life, which is lived now mostly in the instantaneous ‘virtual space’ of social media. Judging from the tragic news of recent months, random, senseless violence seems to be on the increase. There is social unrest fomenting in the streets and on university campuses, a further sign, perhaps of a deeper anger, despair, and meaninglessness beneath the surface of the culture. And we see revolutionary upheaval, less obviously violent perhaps but more profound, in those areas of life that cut closest to who we are as human beings. What previous generations have taken for granted— for example, that man, woman, mother, and father name natural realities as well as social roles, that children issue naturally from their union, that the marriage of man and woman is the foundation of human society and the optimal home for their flourishing—all this is now increasingly regarded as obsolete and even hopelessly bigoted. Our society is rapidly accommodating itself to these changes: re-inventing the family, inventing new rights and revising its understanding of justice, refashioning the norms and archetypes shaping our children’s imagination, reforming education and even the language, policing the bounds of acceptable thought and speech through new forms of ‘citizen led surveillance’ enabled by social media, and punishing the bigoted transgressors of the emerging orthodoxy by both legal and extra-legal means. It is not difficult to foresee on the horizon the tragic irony that has accompanied most of the revolutions in human history, which promise a new spring time of human freedom and conclude in a dark winter of absolutism.

The America that many of us have taken for granted seems no longer to exist, or at least to be rapidly disappearing. From a Catholic vantage, there were always problems and ambiguities in liberalism, America’s founding political philosophy, and the way it conceived of the individual, freedom, and the nature and purpose of government. Yet most of us have assumed that America’s deep historical roots in the Christian West made it naturally hospitable to the principles of Christian morality and that it even secured the political conditions of possibility for the flourishing of the Church, which would act, for its part, as a kind of moral leaven for civil society. There may have been a hidden cost to this assumption, as our efforts to Christianize liberalism ended up liberalizing Christianity. But this was true in a certain empirical sense, as the by-gone age of brick and mortar Catholicism attests. Catholics could thus feel genuinely at home here, and we could fulfill our duty to serve the common good simply by being good citizens. Though it is an important question whether this was ever true, the point here is that this dream seems to be coming to an end, and the Bishops of the Catholic Church as well as many other Christians around the country are right to see that the end of this dream almost certainly means the erosion of religious freedom as we have known it in America and throughout the West.

While every effort should be made to defend religious freedom by legal and political means, these efforts are unlikely to prove successful over the long term. For the issue is not merely the bad will of a few belligerent activists which could be remedied with a dose of benevolence and some ‘live and let live’ tolerance toward fellow citizens holding minority positions. It is rather that the forces set in motion by this revolution cannot easily be recalled or contained within the scope of the law. The swift and decisive response which crushed Indiana’s RFRA legislation and made the simple owners of a pizza parlor in Walkerton, Indiana into objects of international scorn gives us a glimpse into the nature and reach of these forces and of their capacity to impose their will by extra legal means. It is unclear what protections the courts could provide against such action had they been inclined to do so, which they are obviously not. Instead a slew of court decisions up to and including Obergefell have effectively defined perennial Western and Christian wisdom as irrational and bigoted, an opinion which concurs with the cultural consensus of this ruling elite whose power increasingly resembles the subtle form of totalitarianism defined by Hannah Arendt: not the ‘rule of one,’ the tyrant who controls the levers of state, but rather ‘the rule of nobody’—not to be confused with the absence of rule—our submission to a system of our own creation with no outer horizon or controlling center, no levers to pull, and thus no responsible parties. This more subtle absolutism of liberal society consists not in the fact that it dictates everything one can and cannot do—indeed liberalism generates an endless plurality of private options—but rather in the fact that it is the all-encompassing whole beyond which there is nothing and within which these options are permitted to appear. This more thoroughgoing absolutism relies less on the police power of the state and the force of law than on the unaccountable power of bureaucracy and the overwhelming power of media to, well, mediate what counts as the real world. This is why it more perfectly approaches the more subtle kind of totalitarianism envisioned by Arendt, because its mechanisms of enforcement are internal as well as external. In a perfectly absolute society, whose rule was indeed total, no one would ever know he was being coerced. Rather there would simply be truths that could no longer be perceived, ideas that could no longer be thought, experiences that could no longer be had… and no one would know what they were missing.

He goes on to lay out a vision of the crisis as not primarily political (though political it is), nor primarily religious (though it is religious), nor legal or social, though it entails both those things. No, the fundamental nature of the crisis is metaphysical and anthropological. What is real? What is man? These are the questions faced not by theological and philosophical faculties, but by all of us. And most of us don’t even know it.

Hanby contends that we have come to see the body as a technology, which is basically a way of seeing the world. The Sexual Revolution, he argues, is “the human face of the technological revolution” — and this radically affects the way we see ourselves and the world. In brief, the body is regarded as something we can alter as we like, to achieve our desires. There are no natural limits, because there is no meaning inherent in Nature.

The key part of Hanby’s talk focuses on whether or not the instrumentalization of all things human is an inescapable function of the liberal political and social order. He believes it is, and that this comes from the modern conception of freedom as the power to effect our will. I won’t get into that here, but the important thing to take away is that in an order based on this concept of human freedom, and indeed on this concept of reality, is one to which the traditional Christian view cannot be reconciled. Hanby tells me he is going to develop that argument more fully in the essay he is writing.

For me, the real point — and the most important Benedict Option point — is found in these lines near the end of Hanby’s speech

Even if there were an abundance of tolerance and good-will, there is little indication that the brave new world which we have ushered in can accommodate a Christianity which refuses to conform to its ideal of human nature and truth. The more urgent questions is whether we can resist the enormous pressure to accommodate ourselves to this post- human ideal.

Think of it this way. It’s not hard for Christians to imagine George Orwell’s vision of totalitarianism coming to bear on their communities from a hostile state. It is much harder for Christians to recognize the threat posed by the Aldous Huxley view of dystopia — that is, a totalitarianism that is welcomed by those enslaved to it because it makes them comfortable, and because they don’t recognize it for what it is.

This is the greatest threat to authentic Christianity, and the one that I foresee the Benedict Option attempting to combat. Hanby references this long interview that Bill Kristol did with David Gelernter of Yale, in which Gelernter discusses how we have become a country where young people, even the smartest ones, like his Yale students, know nothing:

My students today are much less obnoxious. Much more likable than I and my friends used to be, but they are so ignorant that it’s hard to accept how ignorant they are. You tell yourself stories; it’s very hard to grasp that the person you’re talking to, who is bright, articulate, advisable, interested, and doesn’t know who Beethoven is. Had no view looking back at the history of the 20th century – just sees a fog. A blank. Has the vaguest idea of who Winston Churchill was or why he mattered. And maybe has no image of Teddy Roosevelt, let’s say, at all. I mean, these are people who – We have failed.

More Gelernter:

They know nothing about art. They know nothing about history. They know nothing about philosophy. And because they have been raised as not even atheists, they don’t rise to the level of atheists, insofar as they’ve never thought about the existence or nonexistence of God. It has never occurred to them. They know nothing about the Bible. They’ve never opened it. They’ve been taught it’s some sort of weird toxic thing, especially the Hebrew Bible, full of all sorts of terrible, murderous, prejudiced, bigoted. They’ve never read it. They have no concept.

It used to be, if I turned back to the 1960s to my childhood, that at least people have heard of Isaiah. People had heard of the Psalms. They had some notion of Hebrew poetry, having created the poetry of the Western world. They had some notion of the great prophets having created our notions of justice and honesty and fairness in society

But these children not only ignorant of everything in the intellectual realm, they have been raised ignorant in the spiritual world. They don’t go to church. They don’t go to synagogue. They have no contact – the Americans. Some of the Asians are different. Some of the Asians – and, of course, the Asians play a larger and larger role. But I think, from what I can tell, the Asians are moving in an American direction, and they’re pulling up their own religious roots.

But when I see a bright, young Yale student who has been reared not as Jew, not as a Christian, outside of any religious tradition, why should he tell the truth? Why should he not lie? Why should he be fair and straightforward in his dealings with his fellow students? He has sort of an idea that’s the way he should be, but why? If you challenge him, he doesn’t know. And he’ll say, “Well, it’s just my view.” And I mean, after all everybody has his own view.

American Christians are no better than anybody else. When I was at the First Things symposium in the fall of 2014 — the one at which Michael Hanby presented this paper, which you really should read — I was profoundly struck by what younger Catholic theologians were saying about the students on campus today: that most of them know nothing about their Catholic faith, even if they’ve been through Catholic education. They are blank slates. The one thing they do know is that they desire. They don’t know how or why to order their desires.

I had a very similar conversation with professors at a couple of Evangelical colleges. Many of the kids — and they’re all bright, kind kids — come to college knowing nothing but shallow youth-group pieties. That is all they have been given by their churches, their parents, and their communities. They are virtual blank slates. I’ll never forget the professor who said to me, the emotion audible in his voice, “We only have four years with them, and we do the best we can,” but it’s never enough.

We cannot keep going like this in the American church, or there won’t be an American church. There may be churchgoers, but they will have been catechized not by the church, but by the culture. They will accept whatever the culture tells them to believe, without protest.

In First Things today, poli sci professor James Rogers writes about the “ecclesiastical failure of Christian America.” We have been a go-along-to-get-along people since the country was founded — and now that the tide of cultural Christianity has receded, we stand in the surf with our nakedness present for all to see. Excerpt:

Fast forward to today when we hear about the need for churches to exercise the so-called Benedict Option. Basically, it means little more than churches need actually to reflect the full reality of what they’re supposed to be in the first place. But American churches are out of practice, ironically because of the power they once exercised over American culture.

As a result of developing the last 200 years of a “nation with the soul of a church,” Christians don’t have the ecclesiastical practices and habits that allow them easily and naturally to be fullness of the church.

These habits and practices, or the lack thereof, created all sorts of problems, even ignoring how they obscured the Gospel. Evangelicals naturally, if idolatrously, turned toward politics rather than to ecclesiology for the solution to the moral disorientation they saw in society. The Moral Majority, school prayer, “Take back America for Christ” campaigns, all reflected more of an attempt to reassert ownership of America’s moral public space than to save souls or spread the Kingdom or strengthen the life of the community of disciples in the churches. Recovering a full-orbed ecclesiology for the Church—not for the Church in the abstract, but for the practical lives of Christian layfolk and leaders in the churches—must be in initial imperative for the Church today.

Well, yes, up to a point. I think the Benedict Option is something more radical than “the church being what the church ought to be,” though it certainly entails that. Here’s what I mean. I was talking earlier today with some publishers who had queries about my Benedict Option book proposal, and they wanted to know why this moment is different from all previous moments. My answer is this: because the culture has come to reflect a post-Christian understanding of the nature of humankind, of truth, and even of reality. We have not been in this place in the West since the fall of Rome. I didn’t say that (though I believe it); Pope Benedict XVI did.

That sounds airy-fairy and philosophical, but when you try to talk with people — not just young people, but with ordinary Christians — about what they believe and why they believe it, they quickly reveal themselves to be Moralistic Therapeutic Deists. I’m not talking about people being unable to give articulate, complex theological accounts; I’m talking about people being able to state, however basically, what human beings are for, how we can know what’s true, what families are for, who God is, and so forth — and to build lives in public and private based on those understandings.

The young people in Gelernter’s classes didn’t get that way on their own; they got there because their parents and their pastors gave them stones, not bread. And their parents too may have been given the same thing. Yes, the church in America is failing, but the church isn’t just the institution and its leadership, but every mother and every father, and their children. This is, as Hanby said in his speech, “a winnowing time.” It will not be enough to have the correct thoughts in our heads, or to hear the correct sermons at church. We have to do what Robert Louis Wilken said, and regain the ability to tell ourselves our own story, and to instantiate it in our local culture (e.g., in our churches, in our families). And we have to radically change our practices to make those truths live in tangible, deeply felt ways. The faith can no longer be part of our lives; it has to be our lives in a thick and binding way.

And — here is the bad news — we have to prepare ourselves to suffer for our faith. To deny ourselves. This gets to the sclerotic heart of comfortable American Christianity. But don’t be discouraged, says Michael Hanby. The truly hopeless person is the blind Christian optimist who trusts in the present order, and who is willing to accept the limits that order puts on our imagination. If we go along to get along, we will forget who we are and who we were made to be. We will, in our Babylonian exile, forget Jerusalem. Jesus said, “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” Our freedom depends on our knowing the truth, and our knowing the truth, and passing it on to our children, depends on establishing ourselves in fundamental opposition to the present and emerging cultural order — which, if we understand ourselves as Christians rooted in our tradition, we cannot help doing.

If you aren’t consciously countercultural, you aren’t going to be Christian for long. Contemporary culture — and that includes normative religious worship and life — severs us from our roots, and from the divine order. It cannot do otherwise, not if freedom is found in liberating the individual Self and its will. The question facing American Christians is, following Hanby: “Can we resist being assimilated to this post-human, post-Christian ideal?”

I don’t think most of us will be able to. But I’m talking to the people who want to fight. I’m talking to the people who know why the martyrs died as free men and women, and why their stories rightly give us hope. You can follow Your Best Life Now to the death of Christianity, but some of us, we will find another way to go, even if we have to pioneer it ourselves.

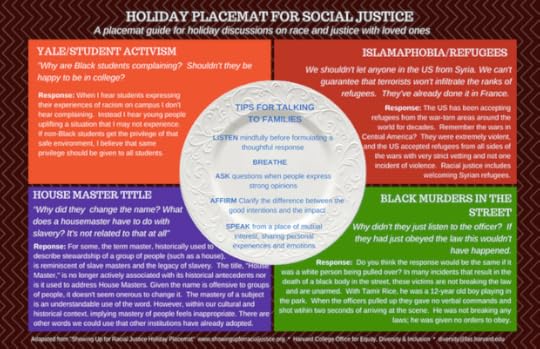

Woe! Harvard Home For the Holidays

Is there anything more insufferable than a college student at home for the holidays, sitting around the dinner table lecturing his family on politics and social justice? Woe betide families of Harvard undergraduates, who are being instructed by the university on what to say to their benighted kinsmen over the upcoming break. The Crimson reports that the university put propaganda placemats in dining halls the other day:

Dubbed “Holiday Placemat for Social Justice” and described as “a placemat guide for holiday discussions on race and justice with loved ones,” the placemats pose hypothetical statements on those topics and offer a “response” to each of those in a question and answer format. For example, under a section entitled “Yale/Student Activism,” the placemat poses the question, “Why are Black students complaining? Shouldn’t they be happy to be in college?” and suggests that students respond by saying, “When I hear students expressing their experiences on campus I don’t hear complaining.”

In the center of the placemat are what it calls “tips for talking to families,” with recommendations such as “Listen mindfully before formulating a thoughtful response” and “Breathe.”

The placemats are endorsed by Harvard administrators. The product of a collaboration between the College’s Office for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion and the Freshman Dean’s Office, the placemats first appeared in Annenberg last week. Jasmine M. Waddell, the freshman resident dean for Elm Yard, described the placemats’ goal as giving freshmen strategies for discussing those issues with their families over winter break.

Via Jonathan Haidt, who nails it:

Harvard comes clean: Goal is to teach students WHAT to think, not how. And what their FAMILIES should think too: https://t.co/aUcfcHAZSR

— Jonathan Haidt (@JonHaidt) December 17, 2015

It’s a safe bet to assume that anything that comes from a college’s Diversity Office, or that is labeled “social justice,” is b.s. of the highest order, and deserves to be ridiculed mercilessly. I hope the next president elevates the South Park production company to cabinet-level status.

When your Harvard undergraduate comes home for the holidays and undertakes to preach about politics at the dinner table, ask yourself, “What would Eric Cartman say?” Then say it over and over again, until the SJW runs sobbing from the table.

UPDATE:

Here’s an image of the placemat. It’s actually worse — and more ridiculous — than I thought. It’s like a cross between a news quiz and an SJW catechism. You know what I think? That some Harvard faculty member should sent out an e-mail questioning whether it’s the place of a university to instruct and police its undergraduates in this way. Heh heh:

Muslim God, Christian God

By now you will have heard about Wheaton College’s suspension of a professor over a theological matter. An excerpt from the Evangelical college’s statement:

On December 15, 2015, Wheaton College placed Associate Professor of Political Science Dr. Larycia Hawkins on paid administrative leave in order to give more time to explore theological implications of her recent public statements concerning Christianity and Islam. In the interim, College leadership has listened to the concerns of its students expressed through social media, a peaceful demonstration and one-on-one meetings with the administration.

As a Christian liberal arts institution, Wheaton College embodies a distinctive Protestant evangelical identity, represented in our Statement of Faith, which guides the leadership, faculty and students of Wheaton at the core of our institution’s identity. Upon entering into a contractual employment agreement, each of our faculty and staff members voluntarily commits to accept and model the Statement of Faith with integrity, compassion and theological clarity.

Contrary to some media reports, social media activity and subsequent public perception, Dr. Hawkins’ administrative leave resulted from theological statements that seemed inconsistent with Wheaton College’s doctrinal convictions, and is in no way related to her race, gender or commitment to wear a hijab during Advent.

Wheaton College believes the freedom to express one’s religion and live out one’s faith is vital to maintaining a pluralistic society and is central to the very reason our nation was founded, enabling us to live together despite our deepest differences. Equally important is the freedom of religious organizations to embody their deeply held -convictions.

Wheaton College rejects religious prejudice and unequivocally condemns acts of aggression and intimidation against anyone. Our Community Covenant upholds our obligations as Christ-followers to treat and speak about our neighbors with love and respect, as Jesus commanded us to do. But our compassion must be infused with theological clarity.

The freedom to wear a head scarf as a gesture of care and compassion for individuals in Muslim or other religious communities that may face discrimination or persecution is afforded to Dr. Hawkins as a faculty member of Wheaton College. Yet her recently expressed views, including that Muslims and Christians worship the same God, appear to be in conflict with the College’s Statement of Faith.

Two things from me:

1) I am hardly in a position to say, but it seems to me that the conflict between the professor’s statement and the colleges Statement of Faith is not crystal-clear, nor is the absence of conflict. It’s important to note that the college is not passing definitive judgment, only saying that it is suspending Prof. Hawkins until that determination can be made. I support Wheaton’s action here — not because I think Prof. Hawkins is wrong in her theological pronouncement (though she may well be), but because it shows that Wheaton is serious about safeguarding its Evangelical identity. One reason so many Catholic colleges and universities are Catholic In Name Only is because they don’t do this.

I’m quite sure I would draw the theological lines in different places than where Wheaton has, on a lot of things. The point is that I applaud the college for being willing to take a hard, unpopular stand on doctrine — even if I do not necessarily agree with the teaching it is trying to defend.