Rod Dreher's Blog, page 522

October 28, 2016

Hillary Milhous Clinton’s October Surprise

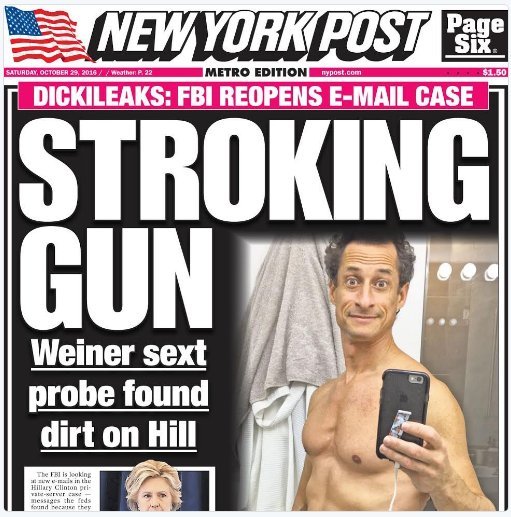

Of course it was Anthony Weiner, the Fredo Corleone of the Democratic Party. Of course:

Federal law enforcement officials said Friday that the new emails uncovered in the closed investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server were discovered after the F.B.I.seized electronic devices belonging to Huma Abedin, a top aide to Mrs. Clinton, and her husband, Anthony Weiner.

The F.B.I. is investigating illicit text messages that Mr. Weiner sent to a 15-year-old girl in North Carolina. The bureau told Congress on Friday that it had uncovered new emails related to the Clinton case — one federal official said they numbered in the thousands — potentially reigniting an issue that has weighed on the presidential campaign and offering a lifeline to Donald J. Trump less than two weeks before the election.

In a letter to Congress, the F.B.I. director, James B. Comey, said that emails had surfaced in an unrelated case, and that they “appear to be pertinent to the investigation.”

The Clintons are compulsively dishonest. If she wins the presidency, as I assume she will (though I’m much less sure about that this afternoon than I was this morning), it will be one damn thing after another. Maybe these e-mails are innocent. Fact is, she was supposed to have turned them over, right? What was she hiding, and why was she hiding it?

UPDATE: May the good Lord preserve the New York Post. What would we do without it?

Against Politicizing Everything

Richard Yuengling, president of Pennsylvania’s Yuengling Brewery, endorsed Donald Trump for president.

After the campaign event, some Yuengling fans have said they would no longer drink the beer.

“Everybody understands that the dollars that we now put into the marketplace have the potential to come back at us,” Brian Sims, a Pennsylvania state representative from Philadelphia, said in an interview on Thursday. “I want my dollars spent in a way that at the very least doesn’t hurt me, and hopefully supports me.”

Mr. Sims, a Democrat who became the state’s first openly gay legislator when he was elected in 2012, called for bars in Philadelphia’s “Gayborhood” to take Yuengling off tap and halt future orders. Two bars have agreed so far, Mr. Sims said, adding that he plans to expand his efforts to bars beyond the L.G.B.T. community.

At the same time, some users on social media have also pledged to stop drinking Yuengling. While it’s unclear how many customers Yuengling could lose, the episode shows the risk that business owners take in dipping their toes in politics.

“It’s not about who the owner wants to vote for; he can vote for whoever he wants,” Mr. Sims said, adding that he has drunk Yuengling since he became of drinking age. “But that support he’s giving is support he has because we’ve given it to them.”

Ridiculous. Of course the guy the Times quotes as one of the leaders of the charge is a gay man. It’s not enough for him to win (Hillary’s up by 7 points in Pennsylvania); he has to make sure that people whose political opinions he doesn’t like are damaged in every way possible.

A reader cracks wise: “Why do people care so much about trivial things? A little apathy goes a long way.” True dat.

October 27, 2016

Norcia In Agony

I have been on the road all day from Baton Rouge to Waco, where, at an academic conference, I will be giving a presentation on the Benedict Option. As you have no doubt heard by now, there were more earthquakes in Italy. The Benedictine monks in Norcia report that their basilica and monastery have been hard hit. Excerpts:

Over the past 24 hours, a powerful series of earthquakes passed through Norcia, once again graciously sparing the lives of the monks and inhabitants to Norcia. Unfortunately, however, it has brought many of the townspeople to the brink of despair and more damage than any of us can yet assess. As before, we are busy at work trying to respond to the crisis on multiple levels. Therefore, my time is short to update all of you, even though you each have found so much time to support us through your prayers and donations. The Basilica fared the worst. Entire walls of decorative plaster crashed to the floor and the dome has begun to cave in. The roof collapsed in two places, leaving the ancient Basilica exposed to all the elements. Most dramatically, perhaps, the Celtic Cross which adorned the 13th century facade came crashing down.

Here is what that façade looked like, from a photo I took in February there:

More from the report by Father Benedict, the subprior:

The 50% of the monastery which had been considered “habitable” after the August quakes has now been damaged far beyond what one might call safe livable conditions. At 10:30 PM last night, 5 of the town monks escaped to San Benedetto in Monte to join the 8 of us already here, where, after a common sip of Birra Nursia Extra, we camped out for a night of turbulence. After a few scant moments of sleep, we rose at 3:30 AM for Matins and started to accept once more that our life is not our own and God had altered our path once again, solidifying it here on the mountain top. Sadly, for the foreseeable future, this means it will no longer be possible for us to offer Mass in the crypt of the Basilica for the public. But, if God wills it, we will soon offer Mass here on the mountain.

The basilica’s crypt contains the altar of Saints Benedict and Scholastica. It was part of the house in which they were born. I took this photo after praying there. I wonder if I will ever see it again:

More:

In closing, and on a note of hope, I want to tell you about a special visitor we had this morning. In an act of both ecclesiastical solidarity and paternal support, and as the ground beneath us continued to tremble, Archbishop Alexander K. Sample of Portland, Oregon, became the first Bishop to offer Mass in the private chapel of our modest dwellings. The Bishop was in Norcia to participate in the fifth annual Populus Summorum Pontificum pilgrimage. Following the earthquake, the pilgrimage’s Norcia events were cancelled, and so the Bishop spent time with our community. He was able to join us for coffee and offered soothing words of support, which we in turn repeat and offer to all of those in the region affected by natural disaster:

“God will bring good to you out of this suffering and this earthquake will become the cornerstone on which generations of monks will build their monastic life.”

If you want to be part of the rebuilding — and I hope you do — click here.

How I wish The Benedict Option was about to be published, so you could read in much greater detail about these monks’ life in common, and what a beacon of light and hope they are. God really is doing something wondrous there in Norcia. Our reader and faithful correspondent James C., who has spent time with the monks in Norcia, writes to say that the town is “in agony” now. The church of San Salvatore, just outside of the city’s walls, collapsed entirely. The core of the church has been there since the 12th century. Here is what it was. James sends this photos too:

These precious 15th century frescoes, all reduced to dust now. No one will ever see them again:

Writes James: “It breaks the heart. What is God’s will in all of this?”

No, The Maginot Line Will Not Hold

Though he never mentions the Benedict Option by name, Claes Ryn writes in TAC a jeremiad against the very idea. We agree that the country, indeed Western civilization, is in a serious crisis. But that’s about it. Excerpts:

Many Christians are calling for a return to moral and religious basics and for a reinvigoration of family and community life. Nothing would seem to be more appropriate and encouraging or to be more conservative. Are not our problems at bottom moral-spiritual? But here as elsewhere habits of avoidance threaten to turn a sound impulse into self-deluding escape.

Self-deluding escapism? Tell me more:

It is common for supposedly “traditionalist” Christians to say that the historical situation has become so bad that little can be done to reverse destructive trends. People of faith must resign themselves to retreating into their own separate spheres, to keep the flame alive in their corner of human existence. Has not Christianity always recognized an inevitable tension between faith and the world?

Quietism in our time! More:

Two objections immediately come to mind. It might be argued first of all that what is needed in threatening historical circumstances like ours is not a general disposition of retreat from challenges but a spirit of moral-spiritual toughness, a readiness and willingness to take on the world. In our era of flight from reality there is a danger that in practice a supposed return to moral-religious basics will turn into a combination of trepidation and dreaminess.

And:

Realizing the limited reach and efficacy of politics must not become an excuse for a general retreat from the front line of life. Granted, different people must play different roles. Those who have chosen the special witnessing of otherworldliness do, by definition, leave ordinary worldly responsibilities to parents, entrepreneurs, doctors, teachers, politicians, soldiers, scientists, et al., although here and there their roles may overlap with those of people active in the world. Most who lead ordinary lives will, and should, give their best energy in family, church, and local community, but these efforts should be influenced as little as possible by sentimental spirituality. What seems most needed is the virtual opposite: a moral-spiritual toughness capable of taking on our historical predicament. We all have a responsibility—small or great depending on our personal gifts and circumstances—to do what might be done to reverse large, dangerous trends. A wish to stay away from potentially painful, daunting tasks, understandable though it is, aids and abets the destructive forces.

This is not the Benedict Option as I have written about it over and over, and write about it in the forthcoming book. More to the point, it is not the Benedict Option as I presented it to a conference earlier this year in which Claes Ryn was in the audience. He should know better. If he was confused on any point, I would have happily shared with him a copy of the speech, had he asked. But as usual with this kind of critic, they wish to argue with the Benedict Option as they imagine it to be, not the Benedict Option as I have explained it.

I started to undertake a point by point refutation of Ryn’s specious claims, but then realized that it would be pointless. However many times, and in however as much detail, as I explain that I’m not saying let’s all head for the hills and cultivate our lotus gardens, they are bound and determined to think so. It’s frustrating to have to argue with people who don’t listen the first time, and who mischaracterize my argument. But until the book comes out, I can give people who don’t read me regularly a pass on this. Someone who sat there and listened to me talk about this in some detail for about an hour, not so much.

You will notice in Ryn’s essay that he has no plan for how to address this current crisis. He simply says:

People who want to make the best of troubling historical circumstances must shake off tempting illusions and other escape mechanisms and employ all available levers and resources. They must avoid the twin forms of denial: retreat and surrender.

Yeah? So what would Prof. Ryn have us do, then? I could be wrong in this Benedict Option stuff, but I prefer the attempts I’m making to think creatively about the crisis to Prof. Ryn’s bah-humbugism, which, absent some detailed explanation of what it means to “employ all available levers and resources,” is really more escapist than anything I’ve put forth. Employ all those things to defend what, exactly? These old conservative generals can’t help fighting the last war, and resting in the confidence that their Maginot Line will hold if we just rally our spirit and reinforce the concrete. What they don’t get is that the Huns have already gone over, through, and around their defenses, and are occupying our territory. The Benedict Option is the Resistance.

How Dante Can Save Conservative Intellectuals

Ross Douthat has a good column up on “What the Right’s Intellectuals Did Wrong” regarding the woebegone state that conservatism finds itself in today. Excerpt:

The second failure was a failure of recognition and self-critique, in which the right’s best minds deceived themselves about (or made excuses for) the toxic tendencies of populism, which were manifest in various hysterias long before Sean Hannity swooned for Donald Trump. What the intellectuals did not see clearly enough was that Fox News and talk radio and the internet had made right-wing populism more powerful, relative to conservatism’s small elite, than it had been during the Nixon or Reagan eras, without necessarily making it more serious or sober than its Bircher-era antecedents.

Some conservatives told themselves that Fox and Drudge and Breitbart were just the evolving right-of-center alternative to the liberal mainstream media, when in reality they were more fact-averse and irresponsible. Others (myself included) told ourselves that this irresponsibility could be mitigated by effective statesmanship, when in reality political conservatism’s leaders — including high-minded figures like Paul Ryan — turned out to have no strategy save self-preservation.

Douthat concludes the essay like this:

History does not stand still; crises do not last forever. Eventually a path for conservative intellectuals will open.

>But for now we find ourselves in a dark wood, with the straight way lost.

That last line, of course, refers to the opening of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and the condition the pilgrim finds himself in when the poem opens. So, let’s go with that for this post. Let’s imagine what the road back to the straight way would be for conservative intellectuals if they used the Commedia as a guide.

The Commedia is a journey in three parts. The Inferno is the pilgrim Dante’s visit to the abode of the damned, which occasions intense self-reflection on his own errors. The Purgatorio is about rebuilding through the hard work of repentance. The Paradiso is about what life in community would be if everyone were living in perfect harmony with God and each other. In that sense, the Commedia is a highly political work, and not simply because in it, the poet Dante offers strong opinions about how Italy is governed, and how it should be governed.

What would the Inferno stage — the merciless self-reflection — be like for conservative intellectuals? What you discover in the Inferno is that all the damned are there because they made idols of particular things, treating contingent goods as ultimate goods, and giving their lives over to achieving those goals.

For example, Farinata degli Uberti is in Hell because he denied that there was life after death, and was therefore a heretic. What you discover, though, is that Farinata’s believing that this world was all there is led him to worship family, honor, and worldly achievement. The point is not that family, honor, and worldly achievement are bad things. The point is that when they are ultimate ends, they distort everything, and can lead one to Hell.

Another example: Brunetto Latini was a statesman, man of letters, and tutor of Dante who is in Hell for sodomy (which was quite common in late medieval and Renaissance Florence). Sex never comes up in the quite tender exchange Dante and Brunetto have in the Inferno. Instead, they talk about literary fame. Brunetto advises Dante to write for the sake of worldly fame. Later in the Commedia, the pilgrim Dante learns that this is exactly the wrong advice, that fame is fleeting. The point the poet Dante is making with the Brunetto in Hell scene is to connect artistic creation as a form of self-worship with infertility. Because in real life, Dante Alighieri looked up to Brunetto Latini as a mentor, this scene is the poet’s way of criticizing his younger self for using his poetic gifts for self-glorification.

Those are just two examples. A third is Pier della Vigna, a real-life figure who had been a top adviser to the Holy Roman Emperor before falling out of his favor and committing suicide. Dante has Pier in Hell as a suicide, but what you learn in their exchange is that Pier wrongly saw all the meaning in his life in terms of worshiping power. When the Emperor, Frederick II, imprisoned him (after a false accusation, in Pier’s account), Pier lost his reason to live, and killed himself. This episode is Dante’s commentary on the corrupting nature of power-worship.

(There are many more examples of the damned that may be relevant to the plight of conservative intellectuals. I just wanted to mention three as a way to show you what Dante is up to. I welcome readers of the Commedia to offer others.)

If conservative intellectuals put themselves through an Inferno walk, what would they discover about themselves and their errors? Off the top of my head, I can think of a few, based on the above characters:

Farinata‘s example should compel conservative intellectuals to reflect on how they lost sight of higher truths for the sake of serving temporal power. Farinata is also a symbol of the destructive power of factionalism, and how anybody who devotes themselves wholly to serving factions (versus the truth, and the common good) will not end well. Intellectuals on the Right who cared more about serving the causes of the Republican Party than the truth need to reckon with this mistake.

Russell Kirk has written:

The great line of demarcation in modern politics, Eric Voegelin used to point out, is not a division between liberals on one side and totalitarians on the other. No, on one side of that line are all those men and women who fancy that the temporal order is the only order, and that material needs are their only needs, and that they may do as they like with the human patrimony. On the other side of that line are all those people who recognize an enduring moral order in the universe, a constant human nature, and high duties toward the order spiritual and the order temporal.

To what degree have conservative intellectuals been Farinatas, living, teaching, and writing as if the temporal order is the only order, even if they profess otherwise?

2. Brunetto Latini‘s example is a useful one for conservative intellectuals who placed more value in being TV, talk radio, or Internet stars than in bearing witness to the truth, no matter how difficult it might have been to tell that truth.

3. And Pier della Vigna‘s sad story is relevant to conservative intellectuals who drew a lot of their sense of self-worth from flattering GOP politicians and corporate leaders.

In his piece, Douthat points out that the abandonment of prudential wisdom by conservative intellectuals during the Bush years and what followed contributed to the rise of Trump. He’s right about that. For example, it should not have taken 13 years after Bush launched the Iraq War for senior members of the party to say it was a mistake — and it sure as hell shouldn’t have taken Donald Trump to say it. But it did. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a good analogue in the Inferno to the vice of imprudence. Then again, every sin is in some way an act of imprudence. The inability of conservative intellectuals to admit error in Iraq, and in economic policy, is rooted in the Ur-vice of Pride.

What about Dante’s Purgatorio? The poet presents it as taking a winding and treacherous path up a mountain, moving towards Heaven. In the Inferno, community is impossible. Everyone is eternally alone. But in this second phase, we see people beginning to help each other, to build the rudiments of community.

In the beginning of Purgatorio, Dante meets Cato the Younger at the base of the mountain. Cato was a suicide, and lived and died before Christ. Yet God, in his mercy, has spared him Hell, and placed him at the base of Purgatory as the figure who welcomes the saved. (In the Catholic theology informing the poem, all those in Purgatory will eventually be purified enough for Paradise. They have been saved by God’s mercy, but need to perfect their repentance.) Why is Cato the Younger here? As I wrote a couple of years ago:

Dante’s placing Cato the Younger here and not in Hell seems to indicate the complexity of the poet’s moral vision. Julius Caesar was the kind of figure for which Dante the poet longed: a strong monarch who would put down factionalism and restore order, which is a prerequisite for genuine freedom (remember, the Commedia is in part a poem about the transition from slavery to liberty). He hails Cato, however, as a virtuous man — one of the best pagan statesmen who ever lived — who fought the good fight for liberty, and died as liberty’s martyr. If I’m reading Dante correctly, Cato is a tragic figure — but God, in His mercy and justice, honored Cato’s integrity by sparing him Hell. Cato stood against Caesar not because he was defending his private interests, but because he was standing for righteousness, and defending his doomed Master, the Republic, for pure and noble reasons. That is worth honoring, in Dante.

So, conservative intellectuals may wish to consider their thinking and behavior towards the GOP and American government in light of Cato the Younger’s self-sacrificial idealism for the common good. To what extent have conservative intellectuals’ efforts been in defense of sound ideals, versus the pursuit of power?

In Canto XIX, Virgil instructs Dante on the nature of Sloth, or acedia, presenting it not so much as laziness as an indifference to the world outside of oneself, from which comes a sense of moral torpor about doing what one must do. Douthat writes of conservative intellectuals:

The first failure was a failure of governance and wisdom, under George W. Bush and in the years that followed. Had there been weapons of mass destruction under Iraqi soil and a successful occupation, or had Bush and his advisers chosen a more prudent post-Sept. 11 course, the trust that right-wing populists placed in their elites might not have frayed so quickly. If those same conservative intellectuals had shown more policy imagination over all, if they hadn’t assumed that the solutions of 1980 could simply be recycled a generation later, the right’s blue-collar voters might not have drifted toward a man who spoke, however crudely, to their more immediate anxieties.

That’s a failure of prudence, yes, but it’s also a failure down to Sloth. That is, the conservative intellectual class did not exercise the will to look beyond their own circles, and apply their intellect to discerning the signs of the times, and prescribing how governing policies should be adjusted in light of changing circumstances. This failure of imagination is a matter of laziness.

In Canto XX, Dante meditates on how the vice of greed has led to bad government in Italy, and destroyed the common good (I wrote about it here). Have conservative intellectuals praised capitalism in a disordered way, at the expense of the moral and communal structures necessary for the common good? The worship of Wall Street and the free market among the Right’s intellectuals is worth considering here.

The best political advice in Purgatorio, though, is in Canto XVI, when Dante enters upon the Terrace of Wrath. There, amid the choking smoke and sparks meant to symbolize Wrath, he meets Marco the Lombard. The pilgrim Dante wants his advice on how and why the world is in such turmoil. As I wrote in this space once, Marco responds:

“Therefore, if the world around you goes astray,

in you is the cause and in you let it be sought…”

Boom, there it is. If you want a world of peace, order, and virtue, then first conquer your own rebel mind and renegade heart. Quit blaming others for the problems in your life, and take responsibility for yourself, and your own restoration. God is there to help you reach your “better nature,” but because you are free, the decision is in your hands.

But you know Dante: there are always public consequences of private vices. In the next line, Marco turns to political philosophy, explaining that as baabies, we are all driven by unformed and undirected desire. If we are not restrained in the beginning, we continue on this path, until we become ever more corrupt. This is why we have the law to educate and train us, and leaders to help us find our way to virtue. The problem with the world today, Marco avers, is bad government, secular and ecclesial — especially that of Pope Boniface VIII (his name cloaked here), a wicked man who leads his flock astray.

The rest of this canto concerns itself with analyzing great political questions of Dante’s time, in light of what comes before. For us, we should focus on how the failure of authoritative moral leadership in the family, in the church, in the school, and in other institutions, has brought about our current crisis. Remember how on the terrace of Envy, Guido railed against the progressive decline in moral order owing to parents not raising their children to love virtue? We see a similar judgment here. Yes, each person must be held accountable for his own sins. But it is also the case that the abdication of authority and responsibility by those who ought to be teaching, guiding, and forming the consciences of the young plays a role. Ignorance of the moral law is ultimately not an excuse, but as ever in Dante’s vision, we are not only responsible for ourselves, but also for our neighbors in the family of God (notice that Marco began his address by calling Dante “brother”). If society’s institutions fail to govern justly and teach rightly, the consciences of others will not be “rightly nurtured,” and will, therefore, be conquered by vice.

Why is this the best advice? Because it reminds conservative intellectuals that all public vice begins privately, and that this is a reciprocal relationship (i.e., public vice gives rise to private vice). And it reminds them that the first place to start rebuilding a just and workable political order is in one’s own heart.

It is significant that Dante receives this advice on the Terrace of Wrath, where forgiven sinners who had given themselves over to Wrath in the earthly life are purged of that tendency before moving on to heaven. Dante the poet had been a Florentine politician before he was abruptly sent into exile after a coup staged by his political enemies. The entire Commedia is his attempt to answer the questions, “What went wrong?” and “How did I go wrong?” By placing the discourse with Marco on this terrace, the poet is illuminating the role the vice of Wrath played in destroying civil order in Italy. Therefore, conservative intellectuals ought to examine their consciences looking for the ways in which they cooperated with or instigated wrath for the political gain of their allies. This is relevant to the Douthat point I quoted above. (And by the way, once the Social Justice Warriors have had their way in stoking and channeling Wrath, destroying the Democratic Party’s internal order, and setting people at each other’s throats, liberal intellectuals will need to ask themselves the same question.)

It pays to re-read Russell Kirk’s canons of conservatism list. Much of the Commedia‘s political meaning — as well as conservatism’s — is summed up here:

It has been said by liberal intellectuals that the conservative believes all social questions, at heart, to be questions of private morality. Properly understood, this statement is quite true. A society in which men and women are governed by belief in an enduring moral order, by a strong sense of right and wrong, by personal convictions about justice and honor, will be a good society—whatever political machinery it may utilize; while a society in which men and women are morally adrift, ignorant of norms, and intent chiefly upon gratification of appetites, will be a bad society—no matter how many people vote and no matter how liberal its formal constitution may be.

The disorder in our polity is a mirror image of the disorder in the souls of its people. That disorder is partly the fault of individuals, but it is also the fault of the institutions that taught us and formed us. It was true in Dante’s day, and it is true in our own.

(Hey, if you like this Dante stuff, consider buying my book, How Dante Can Save Your Life. Also, I will be traveling for much of the day, so please be patient re: my approving comments.)

October 26, 2016

Victor, The Sprightly Genital Gnostic

Says Victor, this confused teenager valorized by elite culture:

“People need to realize it doesn’t matter what living meat skeleton you were born in, it’s what you feel that defines you.”

Had this been presented on national television as wisdom at any time before the last 20 years, it would have been seen as madness.

Gender is built on nature. As Anthony Esolen notes in his forthcoming book Out Of The Ashes, a man can act like a dog, but he won’t be a dog. Victor the Non-Binary Teen can act like a girl or a boy, but he/she is one or the other.

These lies we tell ourselves will not stand. You cannot fool nature. But a lot of people are going to be destroyed by these lies before truth is restored.

Live not by lies.

Racist Progressives Demand Segregation

Via Reason‘s Robby Soave, there’s video of a Social Justice Warrior protest at UC-Berkeley last week. Writes Soave:

Student protesters at the University of California-Berkeley gathered in front of a bridge on campus and forcibly prevented white people from crossing it. Students of color were allowed to pass.

The massive human wall was conceived as a pro-safe space demonstration. Activists wanted the university administration to designate additional safe spaces for trans students, gay students, and students of color. They were apparently incensed that one of their official safe spaces had been moved from the fifth floor of a building to the basement.

The video is shocking. These progressives are flat-out racists — and cops stood by and allowed them to get away with it. If this were Ole Miss in 1965, and a wall of white students refused to let black students get to class, and the campus police refused to intervene, we would know exactly what that was all about. But this kind of thing keeps happening on campus, and … crickets.

The University of California — Berkeley is a safe space for racists, provided the racists hate white people. SJWs and the gutless liberals who coddle them: you all are seeding a vicious backlash, and you will deserve it.

October 25, 2016

Trump, Clinton, And Twilight America

Martin Gurri, a former CIA analyst, takes the view from 30,000 feet:

The two candidates are almost laboratory specimens for each side of the struggle. Donald Trump is the anti-everything, not-a-politician politician, whose outlandish statements horrify opponents but bemuse his considerable base of support. At his best, Trump expresses the legitimate frustration of the public with institutions that promise the world yet deliver mostly failure. At his worst and most typical, he is the political equivalent of the vandal in the museum, willing to rip apart traditional arrangements and commitments because he has no clue about their value.

For her part, Clinton is the very model of a modern time-server – a politician whose features have congealed into an institutional mask and whose statements are a hymn to the status quo, to the vast reassurance of her followers and predictable outrage of the antis. At her best, she represents the voice of grown-up responsibility touching US commitments at home and abroad. But at her worst and most typical, Clinton behaves like a divine rights monarch in search of her electoral Versailles, above the law and mere bourgeois morality.

He goes on to say that the real lesson of this election is that the decay of our institutions and their authority has progressed much further than most of us imagined. The rise of Trump is not really a revolt on the right as it is a revelation of what a paper tiger the GOP establishment is. Trump hasn’t killed it; it was dead already, as Jeb Bush’s stillborn candidacy showed (says Gurri). More:

for

In somewhat slower motion than the Republicans, the Democratic Party is unbundling into dozens of political war bands, each focused with monomaniacal intensity on a particular cause – feminism, the environment, anti-capitalism, pro-immigration, racial or sexual grievance. This process, scarcely veiled by the gravitational attraction of President Obama and Clinton herself, will become obvious to the most casual observer the moment the Democrats lose the White House.

After all, Gurri says, an elderly, marginal Vermont socialist won 40 percent of the vote against the greatest living embodiment of the Democratic Party establishment.

Gurri goes on to say the strongest political forces on both left and right are those who “have become unmoored from history.”

The thrust of political passion, here and everywhere, is toward a republic of purity and virtue: a blank slate. The voices of moderation and keepers of our political traditions have been cowed into silence. They have nothing of interest to say in any case.

Read the whole thing. Last year, Virginia Postrel wrote about Gurri’s “Fifth Wave” theory of how the digital information revolution is overthrowing old hierarchies. Excerpts from her column:

Information used to be scarce. Now it’s overwhelming. In his book “The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium,” Gurri considers the political implications of this change. He argues that the shift from information scarcity to abundance has destroyed the public’s established trust in institutional authorities, including media, science, religion, and government.

“Once the monopoly on information is lost, so too is our trust,” Gurri writes. Someone somewhere will expose every error, every falsehood, every biased assessment, every overstated certainty, every prejudice, every omission — and likely offer a contrary and equally refutable version of their own.

That is a powerful observation, and a true one. Over a decade ago, in the first wave of the Catholic Church’s sex abuse crisis, a journalist friend e-mailed to say that he was glad all that had been hidden was now coming to light, thanks to the Internet — but he also wondered if any of our institutions could survive this media environment we had entered into, with the Internet. That was exactly the right question, as is far clearer today. That, it appears, is the basis for Gurri’s theory. As Gurri makes clear, it’s not that these institutions will be quickly destroyed by the inability to control information, but rather that they will hemorrhage authority over time.

Back to Postrel. Gurri is no radical, but rather, in his own words, is an “uncomplicated defender of our system of government.” But, writes Postrel, Gurri also knows from his long career in the CIA how much butt-covering and other forms of mutual protection and shielding from accountability exists within institutions and organizations. The problem we all face is that we expect more of our institutions than they can deliver, and when they can’t, we assume that it’s only because they are horribly corrupt.

I get that. I was telling someone not long ago that a decade on after losing my Catholic faith, I recognize that I had done something that many of my Catholic friends who were as angry at the institutional church as I was had not done: expected more from the Church than it could deliver. The problem with this is that it is far, far too easy for people to grow cynical and tolerant of things that ought not be tolerated. On the other hand, my idealism laid the groundwork for the unraveling of my Catholicism. When I entered the Orthodox Church, I made a deliberate decision to have not one jot more trust in the institution than I had to for the maintenance of my faith (e.g., trusting in the validity of the sacraments). This was instinctive, but also wise. I find myself much less shaken by clerical scandals now.

That move may have kept me from having unrealistic expectations of the institutional church, but it did nothing to restore much faith in the institution as a political entity. I’m not talking about electoral politics. I’m talking about politics in the more basic sense of the way any group of people governs itself. In the past, I would have given the church (Catholic, Orthodox, whatever) the presumption of trust. Now, my reflexive stance is one of suspicion and skepticism. An Orthodox priest who had seen how the sausage is made near the top once said to me that the further away one is from the upper levels of the hierarchy, the easier it is to be steadfast in one’s faith. I have heard similar statements from Christians in other churches. It is no doubt true of all institutions, because institutions are administered by humans.

Thing is, though, every society needs institutions to function, and moreover, it needs to have basic confidence in its institutions to function. It’s not that people have to believe that the institutions are perfect. They do have to believe that the institutions can be trusted to be sound, to be governed by just and competent people. When institutions lose that basic level of credibility, it’s very, very hard to earn back. It is also very, very hard for people within the leadership class of institutions to grasp when trust in their leadership is eroding. This is the story of the Republican Party this year. If Gurri is correct, it is, or eventually will be, the story of all institutions in the age of total information.

Eminent Victorian Walter Bagehot’s famous observation about the importance of keeping the monarchy shrouded in mystery — “We must not let in daylight upon magic” — for the sake of preserving its authority remains true. The more you see of how an authoritative institution works, the harder it will likely be for it to maintain its authority. On the other hand, as we’ve seen, institutions don’t have nearly the power to keep the daylight out that they once did.

It is worth contemplating, though, that in some cases, the more information we have about the workings of a particular institution, the less we may know about its true nature. I wrote about that here. This is a real problem for us today, one I think few of us grasp. For example, the more we learn about the way legislative politics really works in Washington, the harder it is to trust and respect the institutions of our government. Knowledge, though, is more than the accumulation of facts. A three-ring binder filled with accounts of gross incompetence and corruption on Capitol Hill by no means tells the story of the incredible achievements of our constitutional democracy, and why they are so important to cherish and defend. A hundred thousand venal clerics do not outweigh a single St. Francis — but St. Francis is as much a product of the Church as they are. And so on.

But I digress.

Back to Postrel’s column on Martin Gurri. Gurri says that Barack Obama ran as an outsider in 2008, and, interestingly, ran again as an outsider in 2012. It is well known in Washington that the president has remained largely aloof from Congress, and that this has hurt his effectiveness in the nuts and bolts of governing. Postrel, writing in December 2015:

Obama, Gurri suggests, “represented a new and disconcerting development in democratic politics: the conquest of the Center by the Border, and the rise of the sectarian temper to the highest positions of power.” It’s easy to imagine a President Ted Cruz, representing a different brand of border sectarian, pursuing a similar approach.

Then there’s Donald Trump. By stoking magical thinking about what government can do, elite distrust of what the public wants, and sectarian rage at government failures, Trump feeds the nihilism that makes this period of transition so perilous. Some men just want to watch the world burn.

That last paragraph holds up quite well in late October 2016.

Where does the Benedict Option fit into Gurri’s theory? Or, more to the point, I’ve been talking about this Ben Op idea since at least 2006 (it’s the last chapter of Crunchy Cons), so why didn’t it really take off until 2015-16? My guess is that for whatever reason or reasons, a critical mass of people began to sense that the fabric of society really was unraveling (this is Gurri’s general view, as you’ve seen). For orthodox Christians, the 2015 Indiana RFRA debacle and Obergefell were tipping points at which Alasdair MacIntyre’s analysis (whether or not they had ever heard of him) began to make intuitive sense.

As readers will see when The Benedict Option comes out in March, the general idea addresses a world that, for Christians, is fast crumbling. What do we do when the old structures barely stand? To be precise, for orthodox Roman Catholics (for example), there’s no question that the Roman Catholic institution still maintains its divinely granted authority. That’s what it means to be a Roman Catholic. They aren’t questioning that authority. But in far too many cases, orthodox Catholics can no longer trust their local parishes, their Catholic schools, and their Catholic universities to teach and uphold the Catholic faith, or at least not in a way that is coherent and persuasive. Additionally, orthodox Catholics in far too many cases can no longer trust their fellow Catholics to do the same. (Understand, I’m not singling out Catholics; this is more or less true for all small-o orthodox Christians in the West today.) Philip Rieff wrote:

The death of a culture begins when its normative institutions fail to communicate ideals in ways that remain inwardly compelling, first of all to the cultural elites themselves.

By that standard, Christian culture in the West is fast approaching the rigor mortis state. This fact is concealed from most Christians today, in both the leadership and the followership classes, because they haven’t thought to notice the signs, or they have noticed the signs, but prefer not to think about them. If you’re a believing orthodox Christian, what do you do? The answer will look different depending on your own faith tradition (Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox), and your own local circumstances. The point is, though, that you have to do something, and do something radical, to preserve ways of living out the faith that can endure and thrive through the tumultuous time of transition.

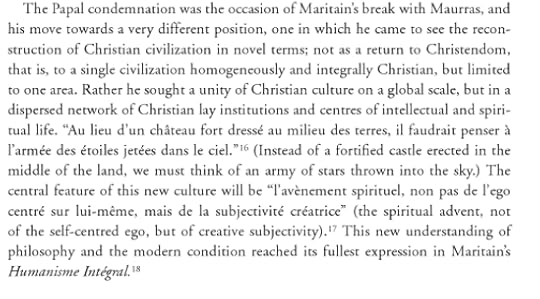

The Benedict Option is not, and must not be, an attempt to establish what Gurri calls “a republic of purity and virtue.” Purity and virtue are ideals to which we should strive, but in Gurri’s case, he’s talking about the delusions of utopianism. Rather, the Ben Op tries to establish local outposts of fidelity and resilience. There’s a great line from the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, written in the 1930s, in which he suggested how believers living in the unraveling of the West — which was well underway by that time — should organize themselves communally to resist. Maritain refused the political militancy of Charles Maurras’ Action Française movement, a far-right Catholic nationalist force condemned in 1926 by the Vatican. From Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age:

Screenshot from Charles Taylor’s “A Secular Age,” p. 744

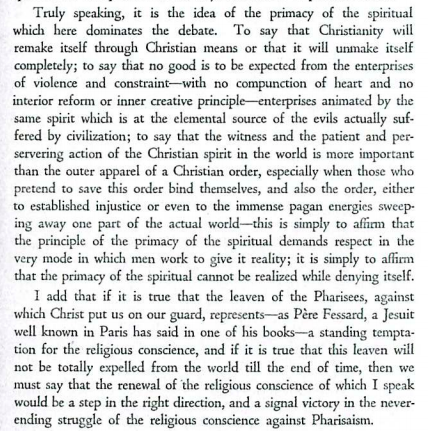

Here is a link to an English translation of the 1939 Maritain essay that introduced his idea of integral humanism. Note this passage in particular:

Note well the relevance of this to our own time and place. Maritain says that “the primacy of the spiritual” over the political is key. If we use un-Christian means to defend and restore Christianity, we will fail. It is more important to maintain the steadfast witness of the Christian spirit than the “outer apparel of a Christian order, especially when those who pretend to save this order bind themselves, and also the order, either to established injustice of even to the immense pagan energies sweeping away one part of the actual world.”

The renewal of religious (Christian) conscience must precede the renewal of politics. This is a fundamental principle of the Benedict Option. I heard an echo of Maritain’s vision in Russell Moore’s Erasmus Lecture (watch it here). The world that has been unraveling since before Maritain’s time is reaching a crisis point, as Gurri says, and all manner of people will be re-binding the tatters into tight knots, hard as a fist.

We orthodox Christians are going to have to re-bind too, and in forms strong enough to withstand the forces trying to tear us apart from our faith, our history, and each other. But to be true to our faith, we are not free to do this according to the patterns emerging in this world. The barbarians continue to sack the fallen imperial city, and even if it were desirable, it is not going to be possible to shore it up. We have to ask: What would Saint Benedict do if he were living among us today? We are not going to be able to build a fortress in a field, because a fortress mentality is not authentically Christian. This is why we have to seek instead to deploy an army of stars against the darkening sky.

The election next month will resolve only one question: who will sit in the White House for the next four years. The unraveling will continue. Christian or not, right, left, and otherwise, you had better be ready for it.

UPDATE: See Ben Domenech’s essay about this stuff. Excerpt:

Ask yourself why so many of Trump’s voters, even the middle class ones, are willing to listen when he says even something as big as a presidential election can be rigged against them. All this is happening because American society is in collapse, and no one trusts institutions or one another. It is due to the failure of government institutions, largely stood up by the progressive left, to live up to their promises of offering real economic security and education and the promise of a better life. It is due to the failure of corporate institutions, who have warped America’s capitalist system to benefit themselves at the expense of others. It is due to the failure of cultural institutions, like the church and community organizations, to help the people make sense of an anxious age.

The point is that while conservative intellectuals have their problems, this is much bigger than anything having to do with conservative intellectuals. The aims of conservatives, whether they are the “populist” or “intellectual” sort (an unsatisfying frame, given that Reagan was both), depends on a certain level of societal flourishing.

The Moral Blindness of Identity Politics

Slate’s Jamelle Bouie analyzes the excellent “Black Jeopardy” skit in which Tom Hanks played “Doug,” a Trump supporter who, along with his two black opponents, discovers that they have a lot in common. Bouie:

Then comes the final punchline, “Lives That Matter.” Obviously, the answer to the question is “black.” But Doug has “a lot to say about this.” Which suggests that he doesn’t think the answer is that simple. Perhaps he thinks “all lives matter,” or that “blue lives matter,” the phrasing used by those who defend the status quo of policing and criminal justice. Either way, this puts him in direct conflict with the black people he’s befriended. As viewers, we know that “Black Lives Matter” is a movement against police violence, for the essential safety and security of black Americans. It’s a demand for fair and equal treatment as citizens, as opposed to a pervasive assumption of criminality.

Thompson, Zamata, and Jones might see a lot to like in Doug, but if he can’t sign on to the fact that black Americans face unique challenges and dangers, then that’s the end of the game. Tucked into this six-minute sketch is a subtle and sophisticated analysis of American politics. It’s not that working blacks and working whites are unable to see the things they have in common; it’s that the material interests of the former—freedom from unfair scrutiny, unfair detention, and unjust killings—are in direct tension with the identity politics of the latter (as represented in the sketch by the Trump hat). And in fact, if Hanks’ character is a Trump supporter, then all the personal goodwill in the world doesn’t change the fact that his political preferences are a direct threat to the lives and livelihoods of his new friends, a fact they recognize.

What Bouie doesn’t seem to get is that black identity politics and the preferences of those who espouse them are a direct threat to the livelihoods and interests of many whites — and even, at times, their lives (hello, Brian Ogle!).

Consider this insanity from Michigan State University, pointed out by a reader this morning. It’s the Facebook page of Which Side Are You On? , radical student organization whose stated purpose is:

Michigan State University has chosen to remain silent on the issue of racial injustice and police brutality. We demand that the administration release a statement in support of the Movement for Black Lives; and, in doing so, affirms the value of the lives of its students, alumni, and future Spartans of color while recognizing the alienation and oppression that they face on campus. In the absence of open support, MSU is taking the side of the oppressor.

Got that? Either 100 percent agree with them, or you are a racist oppressor. It’s fanatical, and it’s an example of bullying. But as we have seen over the past year, year and a half, Black Lives Matter and related identity politics movements (Which Side Are You On? says it is not affiliated with BLM) are by no means only about police brutality. If they were, this wouldn’t be a hard call. No decent person of any race supports police brutality. To use Bouie’s terms, the material interests of non-progressive white people are often in direct tension with the identity politics of many blacks and their progressive non-black allies. This is true beyond racial identity politics. It’s true of LGBT identity politics also. But progressives can’t see that, because to them, what they do is not identity politics; it’s just politics.

You cannot practice and extol identity politics for groups favored by progressives without implicitly legitimizing identity politics for groups disfavored by progressives.

Good luck getting anyone on the left to recognize the fallacy of special pleading when it’s right in front of their eyes.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers