Rod Dreher's Blog, page 500

January 3, 2017

Pope Francis & Child Abusers

Michael Brendan Dougherty has published a blockbuster column today. Excerpts:

The Catholic Church has long been plagued by sickening scandals involving priests abusing children. And there is reportedly another scandal coming — this one of the pope’s own making.

Two people with direct ties to the Vatican tell me that Pope Francis, following the advice of his clubby group of allies in the curia, is pressing to undo the reforms that were instituted by his predecessors John Paul II and Benedict XVI in handling the cases of abuser priests. Francis is pushing ahead with this plan even though the curial officials and cardinals who favor it have already brought more scandal to his papacy by urging him toward lenient treatment of abusers.

It has to do with something as seemingly dry as curial reform. But Dougherty contends that what’s really going on is Francis is protecting friends and punishing enemies — and using something as critically important as cleaning up the Church’s handling of abuser priests to do it. More:

Rumors of this reform have been circulating in Rome for months. And not happily. Pope Francis and his cardinal allies have been known to interfere with CDF’s judgments on abuse cases. This intervention has become so endemic to the system that cases of priestly abuse in Rome are now known to have two sets of distinctions. The first is guilty or innocent. The second is “with cardinal friends” or “without cardinal friends.”

And indeed, Pope Francis is apparently pressing ahead with his reversion of abuse practices even though the cardinals who are favorable to this reform of reform have already brought him trouble because of their friends.

Consider the case of Fr. Mauro Inzoli. Inzoli lived in a flamboyant fashion and had such a taste for flashy cars that he earned the nickname “Don Mercedes.” He was also accused of molesting children. He allegedly abused minors in the confessional. He even went so far as to teach children that sexual contact with him was legitimated by scripture and their faith. When his case reached CDF, he was found guilty. And in 2012, under the papacy of Pope Benedict, Inzoli was defrocked.

But Don Mercedes was “with cardinal friends,” we have learned. Cardinal Coccopalmerio and Monsignor Pio Vito Pinto, now dean of the Roman Rota, both intervened on behalf of Inzoli, and Pope Francis returned him to the priestly state in 2014, inviting him to a “a life of humility and prayer.” These strictures seem not to have troubled Inzoli too much. In January 2015, Don Mercedes participated in a conference on the family in Lombardy.

This summer, civil authorities finished their own trial of Inzoli, convicting him of eight offenses. Another 15 lay beyond the statute of limitations. The Italian press hammered the Vatican, specifically the CDF, for not sharing the information they had found in their canonical trial with civil authorities. Of course, the pope himself could have allowed the CDF to share this information with civil authorities if he so desired.

Read the whole thing. It brings to mind Francis’s repugnant handling of a case in Chile, relayed in this National Catholic Reporter story in October 2015. Excerpt:

On Oct. 2, a Chilean news channel brought to light a May 6 recording of Pope Francis defending Bishop Juan Barros, who was recently assigned to Osorno, Chile, despite allegations that the new bishop covered up clergy sex abuse by a priest in the 1980s and 1990s.

Though evidence of the priest’s abuse was verified by Chile’s judicial court, statute of limitations allowed Fr. Fernando Karadima to dodge prosecution. When a separate Vatican investigation found the priest guilty of abuse, he was condemned in 2011 to a life of prayer and penance in a convent outside of Santiago.

“[The diocese] lost its independence once it let its head be filled with what politicians say, who are judging a bishop without any evidence, even after 20 years as bishop,” Francis said in the May 6 recording, before a group of Chilean Catholics in Rome who asked the pope to send a message to those in Osorno disappointed by the arrival of Barros. “Think with your heads and do not be led by the noses by the lefties who orchestrated this whole thing,” he said in Spanish, as translated by NCR.

Though Barros was never tried for covering up Karadima’s abuse, testimonial evidence has suggested Barros destroyed incriminating correspondence, while other victim testimonies claimed Barros was present during the sexual acts. Though Chilean courts uphold the testimonial evidence, Barros has denied the allegations and has never faced a canonical or civil case.

Francis appointed Barros bishop of Osorno in March, meeting stiff resistance by its people, most notably demonstrated by the hundreds of protestors at Barros’ installation Mass March 21. Francis made the appointment despite the objections, which haven’t abated.

In the video from May, Francis said, “The only charges brought against Barros were discredited by the judicial court, so please do not lose serenity,” he continued. “Osorno suffers, yes, but for being foolish, because they do not open their hearts to what God says, and instead get carried away by all this silliness that everyone speaks of.”

“To what God says.” Hey, God has forgiven, you ungrateful people of Osorno, so why can’t you? Besides, I’m the Pope. Who are you to question?

As ever with church leaders who talk about reform, don’t listen to what they say, but rather watch what they do.

A: ‘Juan LaFonta, Juan LaFonta, JUAN LAFONTA!’

I cannot stop watching this spot for a New Orleans barrister, and featuring transgender bounce superstart Big Freedia, who ran into a spot of legal trouble herself over Section 8 housing fraud.

Juan LaFonta, baby! Watch that spot and you will never, ever extract that earworm from deep inside your skull. If Trump doesn’t name him to Scalia’s seat, I’d say he’s got an inside track on being 2018’s Rex.

Neoliberalism Vs. Medievalism

Excerpts:

Until fairly recently, it was rare to find Americans who were passionate about both medieval history and contemporary politics. Barring the odd Christian conservative, medievalists tended to lean left: a Marxist grad student, say, mucking around in land ownership patterns to show how past inequalities gave birth to present ones, or an environmentalist activist, perhaps, fascinated with vegetable-dyed handspun clothing. But when Americans invoked historical events in politics, they tended to be more recent—the founding of the republic; the struggle against slavery and segregation; victory over Nazi Germany.

This has changed. Since the September 11th attacks, the American far right has developed a fascination with the Middle Ages and the Renaissance—in particular, with the idea of the West as a united civilisation that was fending off a challenge from the East. The trend has been prodded along by the movement’s discovery of its European counterparts, which have used medieval and crusader imagery since the 19th century. This is troubling to many of those who study the Middle Ages for a living.

Oh, bother. More:

In a recent essay in the popular academic blog “In the Middle” Sierra Lomuto argued that medievalists had “an ethical responsibility to ensure that the knowledge we create and disseminate about the medieval past is not weaponised against people of colour and marginalised communities in our own contemporary world.”

In other words, the Middle Ages are worth studying only if contemporary people draw left-liberal lessons from them about the contemporary world. Ed West, probably a closet Plantagenet, remarks:

as @DouthatNYT says, telling people that an interest and attachment to European history makes you Alt-Right is not the cleverest strategy

— Ed West (@edwest) January 3, 2017

Well, as an odd Christian conservative who is ten weeks away from publishing a book holding up a very early medieval institution — Benedictine monasticism — as a model for us in the 21st century, I have a few things to say.

It’s extremely annoying when contemporary people dismiss the medieval period as little more than castles, crusades and poor hygiene. Doing so says more about modern prejudices than it does about the Middle Ages. If there is a growing interest in the European Middle Ages, shouldn’t we be asking why? The last time this happened in modern times at any popular level was in the 19th century, in the Romantic era’s reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the cold, logical classicism of the Enlightenment. Some of it was silly, some of it was dangerous, much of it was valuable — but all of it came from a widespread sense of profound disruption and dislocation, spiritually and otherwise. There was a general sense that life had become too abstracted, positivistic, and mechanical.

We in the West are in such an era today. For example, globalization has done to the populations of the West what the Industrial Revolution did to rural folks. Post-Christianity has largely finished the job that the Enlightenment started, and the Cult of Reason has proven no more satisfying to the masses today than it was back then. Europe really is once again under serious assault from Islam, though not by Ottoman armies this time (and alas for the Catholic Church, it is led by a Pope who is more into felt banners than tapestries, if you take my meaning).

Can it go wrong? Absolutely, in a thousand ways. For example, the völkisch mysticism that emerged out of German Romanticism gave us the Nazis. But it can also go very right. The Russian Orthodox philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev (d. 1948) called for a “new middle age,” as I wrote in this blog post. Excerpt (from Berdyaev):

In reality the medieval civilization was a renaissance in opposition to the barbarism and darkness which had followed the fall of the civilization of antiquity, a chaos in which Christianity alone had been the light and the principle of order. For long it was believed that this complex and rich period had been a great void in the intellectual history of mankind and of its philosophical thought, when as a matter of fact these centuries had so many excellent thinkers and such diversity in the realm of their thought that noting like it can be found at any other epoch; the things which were substantial and living for them are counted as superfluous luxuries in modern times. A return to the middle ages is then a return to a better religious type, for we are far below their culture in the spiritual order; and we should hurry back to them the more speedily because the movements of negation in our decadence have overcome the positive creative and strengthening movements. The middle ages was not a time of darkness, but a period of night; the medieval soul was a “night-soul” wherein were displayed elements and energies which afterwards shut themselves up within themselves at the appearing of this weary day of modern history.

As I say in that post, Berdyaev was not a proponent of sentimental nostalgia. Rather, he said we today must read the signs of the times, and see ourselves not only as “the last Romans,” observing the passing of an old order, but must also be “watchers for the dawn,”

looking towards the yet unseen day when the sun of the new Christian renaissance shall rise. Perhaps it will show itself in the catacombs and be welcomed by only a few. Perhaps it will happen only at the end of time. It is not for us to know. But we do know beyond any possibility of error that eternal light and eternal beuaty cannot be annihilated by any tempest or in any disorder. The victory of number over goodness, of this contingent world over that which is to come, is never more than seeming. And so, without fear or discouragement, we must leave this day of modern history and enter a medieval night. May God dispel all false and deceptive light.

That’s Berdyaev. As I put it then:

The Benedict Option is the term I use to describe this rising movement for a new Middle Age, a spiritual revolution in a time of spiritual and cultural darkness. The monk was the ideal personality type of the Middle Ages. Few of us will be called to the monastery, but all of us who profess orthodox Christianity are called to rediscover a monastic temperament, putting the service of God before all things, and ordering our lives — our prayer and our work, and our communal existence — to that end. We are going to have to recover a sense of monastic asceticism, and do so in hope and joy, together.

I certainly hope that the longing for a society with characteristics of the medieval era does not give strength to race nationalists, but we should not be surprised if it does. The idea that this is the only really interesting question about neo-medievalism in our current moment is absurdly parochial. One doesn’t expect neoliberals to be excited about a rediscovery of medievalism in all its various expressions, but they would do well to understand the social conditions that are turning people’s minds and hearts back to that earlier period, and to understand why the shortcomings of neoliberalism have called these impulses forward. We have to find a way to make use of the good things about the Middle Ages while resisting the bad things about the period.

The Middle Ages will not recur as they were in the West from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 until Petrarch scaled Mount Ventoux in 1336 and came down with the Renaissance. Time is not circular, but rather is a spiral. The first thing we have to be done with if we are to understand the time we’re entering is the myth of linear progress. This is very hard for neoliberals to do.

House GOP Floods The Swamp

This, from the NYT, is an outrage:

House Republicans, overriding their top leaders, voted on Monday to significantly curtail the power of an independent ethics office set up in 2008 in the aftermath of corruption scandals that sent three members of Congress to jail.

The move to effectively kill the Office of Congressional Ethics was not made public until late Monday, when Representative Robert W. Goodlatte, Republican of Virginia and chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, announced that the House Republican Conference had approved the change. There was no advance notice or debate on the measure.

The surprising vote came on the eve of the start of a new session of Congress, where emboldened Republicans are ready to push an ambitious agenda on everything from health care to infrastructure, issues that will be the subject of intense lobbying from corporate interests. The House Republicans’ move would take away both power and independence from an investigative body, and give lawmakers more control over internal inquiries.

Politico‘s report says in part:

In one of their first moves of the new Congress, House Republicans have voted to gut their own independent ethics watchdog — a huge blow to cheerleaders of congressional oversight and one that dismantles major reforms adopted after the Jack Abramoff scandal.

Monday’s effort was led, in part, by lawmakers who have come under investigation in recent years.

Despite a warning from Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) and Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), House Republicans adopted a proposal by Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.) to put the Office of Congressional Ethics under the jurisdiction of the House Ethics Committee.

The office currently has free rein, enabling investigators to pursue allegations and then recommend further action to the House Ethics Committee as they see fit.

Now, the office would be under the thumb of lawmakers themselves. The proposal also appears to limit the scope of the office’s work by barring them from considering anonymous tips against lawmakers. And it would stop the office from disclosing the findings of some of their investigations, as they currently do after the recommendations go to House Ethics.

And:

The new Office of Congressional Ethics can’t release information to public. Or have a spokesperson. No communication. In any way. Got it? pic.twitter.com/BCVDjn3SmY

— Matt Viser (@mviser) January 3, 2017

Look, I have no problem believing that the OCE ought to have been better run. (Not that I do believe it, only that the claim is plausible.) But to abolish it, and to replace it with this People’s Republic-style puppet office? Are they crazy? This is the lesson a majority of House Republicans learned from the 2016 election: that the voters want members of Congress to be less accountable for their actions, and to make it easier for themselves to milk the system and get away with it?

Every single Republican member who voted in favor of this proposal ought to face a primary challenge in 2018. Again, I am willing to consider the argument that the OCE overstepped its bounds and needed to be reigned in. But to have the first headline-making act of the House Republicans in the Trump era be gutting the House ethics watchdog sends a signal that as far at the GOP on that side of the Hill is concerned, it’s pigs-at-the-trough time? It’s politically idiotic. Do they not grasp how despised and distrusted the governing class is?

You want to return the Democrats to power by showing that Republicans cannot be trusted with it? This is a good first move.

UPDATE: After Trump blasted the GOP Congressional move in a tweet this morning, House Republicans decided to retreat. Good for Trump! You don’t have to believe that good government is near and dear to Trump’s heart to recognize his skill at reading the political moment, and acting accordingly. He’s just put Congress on notice that he will go to the people against them if he sees it in his interest. Impressive.

Oriel

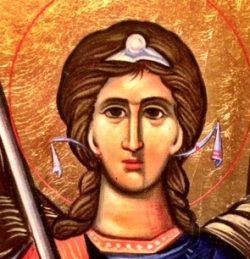

The Archangel Oriel (Uriel)

A friend brought back the above icon of the Archangel Oriel (also known as Uriel) from Greece, and gave it to me for Christmas. I immediately loved it, not least because I have never seen an icon of that archangel. Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael I had heard of, but not Oriel. There’s a reason for this: in 745, the Council of Rome struck Oriel’s name from the list of Archangels commemorated by the Western church. He remained recognized in the Eastern church.

Oriel/Uriel means “light of God” or “fire of God,” hence the image above, of the Archangel bearing fire in his hand. In the Orthodox Church, the blessing of icons typically involves a short formal prayer said by a priest, and the use of holy water, but also can involve the icon being placed upon the altar during a Divine Liturgy. A couple of weeks ago, I took this icon to church, and gave it to our priest with the request that he place it on the altar and bless it. He did place it on the altar at that liturgy, but said afterward that he would need to do the formal blessing. I figured I would pick it up on the next Sunday or so.

As it happened, this past Sunday I was ill and couldn’t make it to liturgy. My wife brought it home to me. Last night I was preparing to say my prayers, and admiring the icon, when I thought, “That face of the Archangel looks familiar. Where have I seen it before?”

Then I remembered the Macedonian film I saw on Sunday afternoon, Before The Rain, which I wrote about here. This is the young Orthodox monk in the first part of the film, Kiril, played by the French actor Grégoire Colin:

Not a perfect likeness, but still, it made me smile.

January 2, 2017

In Crazy Cat Lady News…

From Cosmopolitan.com

Holy Tori Amos! Great Elizabeth Wurtzel! Here’s how this Cosmopolitan story starts:

On the rooftop of her Brooklyn apartment building this past spring, Erika Anderson put on a vintage-style white wedding dress, stood before a circle of her closest friends, and committed herself — to herself.

“I choose you today,” she said. Later she tossed the bouquet to friends and downed two shots of whiskey, one for herself and one for herself. She had planned the event for weeks, sending invitations, finding the perfect dress, writing her vows, buying rosé and fresh baguettes and fruit tarts from a French bakery. For the decor: an array of shot glasses emblazoned with the words “You and Me.” In each one, a red rose.

“It wasn’t an easy decision,” she’d noted on the wedding invitations. “I had cold feet for 35 years. But then I decided it was time to settle down. To get myself a whole damn apartment. To celebrate birthday #36 by wearing an engagement ring and saying: YES TO ME. I even made a registry, because this is America.”

Self-marriage is a small but growing movement, with consultants and self-wedding planners popping up across the world. In Canada, a service called Marry Yourself Vancouver launched this past summer, offering consulting services and wedding photography. In Japan, a travel agency called Cerca Travel offers a two-day self-wedding package in Kyoto: You can choose a wedding gown, bouquet, and hairstyle, and pose for formal wedding portraits. On the website I Married Me, you can buy a DIY marriage kit: For $50, you get a sterling silver ring, ceremony instructions, vows, and 24 “affirmation cards” to remind you of your vows over time. For $230, you can get the kit with a 14-karat gold ring.

Meanwhile, the crazy manifests on the other coast too:

When she graduated in 2011, Dominique went to the Burning Man festival in Nevada, where the theme was “rites of passage.” She decided to help women at Burning Man marry themselves, saying their vows into a mirror. Word got around and some 100 women showed up to tie the knot. Some came wearing wedding gowns; others carried flowers. The scene was emotional, Dominique says. “Imagine hearing 100 women stand in front of a mirror and speak the words that they have always longed to hear.”

“I will never leave myself.”

“I promise to ask for help when I’m suffering.”

“I promise to look in the mirror every day and be grateful.”

“I promise to give you the incredible life that you long for.”

Now 27, Dominique is a self-marriage counselor and minister, offering services including consulting sessions and private ceremonies through her website, Self Marriage Ceremonies, which she runs from her home in northern California.

Read the whole thing — and cue the Woody Allen joke.

Honestly, the barbarians should just roll right in now. We have too much money and too little sense to live.

Bourdain Vs. The Left

Anthony Bourdain is an acquired taste. He happens to be a taste I’ve acquired. Watching the one-hour Bourdain “Parts Unknown” episode about Lyon is the only time a television show has ever made me travel to a place. I’ve seen that episode six or seven times, and probably will watch it that many more times in my life. I actually ate (with James C. and another friend) at one of the restaurants in the show. All of which is to say that I love Anthony Bourdain, even though he’s something of a bastard; in fact, I love Anthony Bourdain in part because he’s something of a bastard. A magnificent bastard who would take that as the compliment I mean it to be. Anthony Bourdain opened up the glories of Lyon to me, and I will always, always owe him for that.

I loved his interview with Reason magazine’s Alexander Bisley. Excerpt:

Bisley: You’re a liberal. What should liberals be critiquing their own side for?

Bourdain: There’s just so much. I hate the term political correctness, the way in which speech that is found to be unpleasant or offensive is often banned from universities. Which is exactly where speech that is potentially hurtful and offensive should be heard.

The way we demonize comedians for use of language or terminology is unspeakable. Because that’s exactly what comedians should be doing, offending and upsetting people, and being offensive. Comedy is there, like art, to make people uncomfortable, and challenge their views, and hopefully have a spirited yet civil argument. If you’re a comedian whose bread and butter seems to be language, situations, and jokes that I find racist and offensive, I won’t buy tickets to your show or watch you on TV. I will not support you. If people ask me what I think, I will say you suck, and that I think you are racist and offensive. But I’m not going to try to put you out of work. I’m not going to start a boycott, or a hashtag, looking to get you driven out of the business.

The utter contempt with which privileged Eastern liberals such as myself discuss red-state, gun-country, working-class America as ridiculous and morons and rubes is largely responsible for the upswell of rage and contempt and desire to pull down the temple that we’re seeing now.

I’ve spent a lot of time in gun-country, God-fearing America. There are a hell of a lot of nice people out there, who are doing what everyone else in this world is trying to do: the best they can to get by, and take care of themselves and the people they love. When we deny them their basic humanity and legitimacy of their views, however different they may be than ours, when we mock them at every turn, and treat them with contempt, we do no one any good. Nothing nauseates me more than preaching to the converted. The self-congratulatory tone of the privileged left—just repeating and repeating and repeating the outrages of the opposition—this does not win hearts and minds. It doesn’t change anyone’s opinions. It only solidifies them, and makes things worse for all of us. We should be breaking bread with each other, and finding common ground whenever possible. I fear that is not at all what we’ve done.

Read the whole thing. He is unkind to Bill Maher, who has it coming.

That’s a good introduction to this great Megan McArdle column, in which she analyzes the mutual intolerance of liberals and conservatives in the US. Excerpt:

While traveling a few months back, I ended up chatting with a divorce attorney, who observed that what we’re seeing in America right now bears a startling resemblance to what he sees happen with many of his clients. They’ve lost sight of what they ever liked about each other; in fact, they’ve even lost sight of their own self-interest. All they can see is their grievances, from annoying habits to serious wrongs. The other party, of course, generally has their own set of grievances. There is a sort of geometric progression of outrage, where whatever you do to the other side is justified by whatever they did last. They, of course, offer similar justifications for their own behavior.

By the time the parties get to this state, the object is not even necessarily to come out of the divorce with the most money and stuff; it’s to ensure that your former spouse comes out with as little as possible. People will fight viciously to get a knickknack neither of them particularly likes, force asset sales at a bad loss, and otherwise behave as if the victor is not the person who goes on to live a productive and happy life, but the one who makes it impossible for the ex to do so.

Read the whole thing. Also, Megan McArdle loves to cook.

The Dark Side Of Tibetan Buddhism

Over the weekend, I ran across this 2010 essay on Reason by Brendan O’Neill, who wrote about his frustration with the way Tibetan Buddhism is whitewashed in Western culture. O’Neill, by the way, is an atheist and a libertarian. Excerpts:

Many Westerners before me have visited Tibet, popped into some monastery on a mountainside, and decided to stay there forever, won over by the brutally frugal existence eked out by Tibetan Buddhists.

I have exactly the opposite reaction. I couldn’t wait to leave the temples and monasteries I visited during my recent sojourn to Shangri-La, with their garish statues of dancing demons, fat golden Buddhas surrounded by wads of cash, walls and ceilings painted in super-lavish colours, and such a stench of incense that it’s like being in a hippy student’s dorm room.

I know I’m not supposed to say this, but Tibetan Buddhism really freaked me out.

The most striking thing is how different real Tibetan Buddhism is from the re-branded, part-time version imported over here by the Dalai Lama’s army of celebrities.

Listening to Richard Gere, the first incarnation of the Hollywood Lama, you could be forgiven for thinking that Tibetan Buddhism involves sitting in the lotus position for 20 hours a day and thinking Bambi-style thoughts. Tibetan Buddhism has a “resonance and a sense of mystery,” says Gere, through which you can find “beingness” (whatever that means).

Watching Jennifer Aniston’s character Rachel read a collection of the Dalai Lama’s teachings in Central Perk on Friends a few years ago, you might also think that Tibetan Buddhism is something you can ingest while sipping on a skinny-milk, no-cream, hazelnut latte.

Or consider the answer given by one of Frank J. Korom’s students at Boston University when he asked her why she was wearing a Tibetan Buddhist necklace. “It keeps me healthy and happy,” she said, reducing Tibetan Buddhism, as so many Dalai Lama-loving undergrads do, to the religious equivalent of knocking back a vitamin pill.

The reality couldn’t be more different.

O’Neill talks about aspects of Tibetan Buddhism that he finds repulsive, but that never get talked about in the West. Then:

Of course, this only means that Tibetan Buddhism is the same as loads of other religions. Yet it is striking how much the backward elements of Tibetan Buddhism are forgiven or glossed over by its hippyish, celebrity, and middle-class followers over here. So if you’re a Catholic in Hollywood it is immediately assumed you’re a grumpy old git with demented views, but if you’re a “Tibetan” Buddhist you are looked upon as a super-cool, enlightened creature of good manners and taste. (Admittedly, Mel Gibson doesn’t help in this regard.)

I am well aware of the fact that I am not the first Westerner to be thrown by Tibet’s religious quirkiness. A snobby British visitor in 1895 denounced Tibetan Buddhism as “deep-rooted devil-worship and sorcery.” It’s no such thing. But what is striking, and what caused me to be so startled by the weirdness, is the way in which this religion has come to be viewed in Western New Age circles as a peaceful, pure, happy-clappy cult of softly-smiling, Buddha-like beings. Again, it’s no such thing. The modern view of Tibetan Buddhism as wondrous is at least as patronizingly reductive as the older view of Tibetan Buddhism as devil-worship.

Read the whole thing. Again, O’Neill’s real beef here is not with Tibetan Buddhism but with the way it is constructed by Western media. I know nothing about Tibetan Buddhism, but regarding religions (Christian and non-Christian) that I do know something about, I find that most mainstream media reporting on it tells us as much about the preferences and biases of the reporter than it does about the religion and its believers.

UPDATE: Judging from the comments, some people think I cited this essay as a way of criticizing Tibetan Buddhism. Not true. I’m quite sure that if I knew more about Tibetan Buddhism, I would criticize plenty of it, while admiring plenty of it. And I’m quite sure that as a cosmopolitan Western atheist libertarian, O’Neill finds much to dislike about Christianity, and would find even more to dislike about more folkish versions of Christian practice. All of that is beside the point. O’Neill is correct to question why Western celebrity and media culture treats Tibetan Buddhism the way it does. This is not the fault of the Dalai Lama.

George Michael & Mr. Creosote

Back on 2003, there was a great story in The Onion:

I thought of that when I read the knickers-knotting hysteria over my comparing the boring life that the other guy from Wham! went on to lead after George Michael split with him, to the self-destructive hedonism of Michael, who died on Christmas Day, aged 53. My conclusion was that Andrew Ridgeley’s failure to prolong and expand his fame was likely a great blessing. George Michael’s immense fame made Ridgeley an afterthought, a punch line — and may have saved his life.

I doubt very many of us could handle fame and fortune well. This is why winning the lottery so often ruins the life of the winner. They say that having a lot of money only makes you more of what you already are. It may magnify your virtues, but it’s easy to see too how it magnifies your vices. As my greatest vice (it seems to me) is gluttony, I could see George Michael money turning me into a version of Mr. Creosote. Whether or not I ever blew up physically, I would be at risk of having the soul of a Creosote, for sure. In Michael’s case, his vices were conventional rock and roll vices — sex and drugs — and that excess probably killed him. It certainly gave him an ugly, tumultuous lifestyle: compulsive, risky sex, often in public toilets or shrubbery, substance abuse, run-ins with the law, prison time. It’s not a life anyone could be proud of, or would want their son or brother to have.

Well, you can’t say that. An excitable person at Wonkette, a guy who doesn’t appear to know that I haven’t been a National Review staffer for 14 years, or a Catholic for over a decade, accuses me of saying that George Michael ought to have been heterosexual. Excerpt:

It’s true that George Michael lived hard and had a lot of trouble with substance abuse over the years, which MAY OR MAY NOT have ultimately had something to do with his brave and bold choice to live proudly, in a society that still broadly rejected gayness, as a gay man who wasn’t ashamed to let you know, early and often, that he liked fu**ing. The gay kind. (For more on this legacy, please read our pal Noah Michelson at the Huffington Post! SPOILER: It’s a story about gay fu**ing, and how George Michael liked it a lot.)

The point is that George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley, though they achieved stardom together, were dealt vastly different cards in life. We imagine that it wasn’t all that difficult for Ridgeley and Bananarama [Note: Ridgeley’s wife was in the ’80s pop group Bananarama] to look at each other heterosexually and say, “Hey, let’s buy a heterosexual farm in the heterosexual country, the conventional way, and get out of all this limelight.” And maybe if society had been different toward gays in the ’80s and ’90s (you know, the age of AIDS), it might have been a conventional gay choice to meet and fall in love with a fellow gay superstar and buy a gay farm in the gay country. ALSO, MAYBE GEORGE MICHAEL WOULD NOT HAVE WANTED THAT.

So, let’s clarify this: it’s society’s fault that George Michael didn’t choose a stable life (“a conventional gay choice”), but anyway, if he didn’t want that, then we must not criticize his choice. Noah Michelson at HuffPo is even more explicit, saying that, “We could all learn a lot from his unapologetic approach to sexuality.” Excerpt:

Excerpt:

Our queer fore-parents worked too hard, and too many died, for us to walk away from the dream of sexual liberation for all of us. That means we must not buy into a broken system that is simultaneously obsessed with and panic-stricken by all things sex. It means we must not accept the sexual status quo that all-too-often results in fake piety in the streets and discreet sleaze in the sheets. It means we must not pretend that Michael never had or loved gay sex. Let’s not sanitize him just because it would make it easier for some of us to eulogize him or love him or play his music for our children or our grandparents.

Michael himself wouldn’t want that. He’d hate it. Consider what he told The Guardian in 2005:

“You only have to turn on the television to see the whole of British society being comforted by gay men who are so clearly gay and so obviously sexually unthreatening. Gay people in the media are doing what makes straight people comfortable, and automatically my response to that is to say I’m a dirty filthy f**ker and if you can’t deal with it, you can’t deal with it.”

Well, that’s just beautiful.

If a straight Christian held the view that at the heart of homosexuality — male homosexuality, at least — is the desire to be a “dirty filthy f**ker,” they would be denounced as the worst kind of homophobe. But that is what these two writers above apparently think. I can think of no heterosexuals who would want their adult children (or siblings) to live by that ethic. I know plenty of people who wouldn’t care if their children were gay, but who wouldn’t want them to live by such an ethic. Because it’s disgusting and dehumanizing.

One of the promises made by same-sex marriage proponents was that it would make it possible for gay men to establish stable partnerships integrated into the broader social order. The idea was that gay men naturally would have done that, if it hadn’t been for anti-gay laws keeping them from doing so. I never believed that was true, because committed monogamy does not come naturally to men. Look at heterosexual societies in which men are no longer expected to be committed to the mother of their children. Most men, when restrained by nothing but their desires (e.g., social custom, religious belief, the law), will behave without restraint.

Noah Michelson even criticizes gay people who would stigmatize rutting in public toilets and under shrubbery, as opponents of “liberation.” It’s a strange kind of liberation that tells people that fulfilling their most animalistic desires is what makes them free. The ancient Greeks had no particular problem with homosexuality, but they knew well that a man that is captive to his own compulsions is not a free man, but a slave.

If George Michael had lived as Mr. Creosote, it would have been perfectly clear to nearly everyone that he was a man enslaved by his passions, and that whatever his musical gifts — and they were extraordinary — the life he lived was in some ways not worthy of emulation. But then, we don’t (yet) have a culture that considers appetite for food constitutive of one’s identity. The p.c. rule of thumb today is that whatever gay people — or any people — decide to do sexually is beyond good and evil, or rather, is good simply because they chose to do it.

It’s a lie that leads to spiritual death, and sometimes physical death too. There are many ways to live a good life — not everybody, gay or straight — has to move to a farm in Cornwall like Andrew Ridgeley — but the way George Michael chose to live privately is not one of them. By the time the Sexual Revolution runs its course, most of America will have become eroticized versions of Mr. Creosote. That clammy old English atheist Philip Larkin had our number.

January 1, 2017

Multiculturalism And Modernity

Reader Anna, who lives in Budapest, recommended to me the 1994 Macedonian film Before The Rain. It’s not available on Netflix or Amazon Prime streaming, but she found a version on YouTube subtitled in English. Unfortunately, it’s also subtitled in Greek, which sometimes makes reading the English subtitles difficult. Still, you get used to it, and you certainly get the gist of what’s being said. It’s worth watching. Here is a link to Roger Ebert’s four-star review. Anna writes:

I’ve just seen your post on Hagia Sophia, and realised there is a film that is an absolute MUST-WATCH for you, based on your recent posts let alone the music. This Macedonian masterpiece won the Golden Lion in Venice in 1994 and is one of the most acclaimed foreign-language films since the fall of communism.

The first reading is that it is about the never-ending circle of violence (in this particular case, between Macedonians and Albanians), but a deeper understanding points to seeing the difference between East and West, tradition and modernity, and why it has become nearly impossible to live in either. The structure is built like a tryptichon and in the centre of it is a Christ-like figure, Aleksandr Kirkov.

Anna is exactly right. I’m going to talk about the movie in this post, trying my best to avoid spoilers, focusing on what it has to say to us about our own challenges today.

The film is structured in three parts. In the first, set in rural Macedonia, one of the new Balkan republics emerging from Yugoslavia’s break-up, a young Orthodox Christian monk tries to protect an Albanian Muslim girl who is hiding from a mob of Orthodox men trying to kill her. The second part, set in London, focuses on the relationship between an unhappily married English photo editor and an acclaimed Macedonian-born photographer, Aleksandr Kirkov, who asks her to leave her husband and return with him to his homeland. He has just won the Pulitzer Prize for his war photography, but he’s burned out on war, and just wants to return to his village and live a quiet life. The third part follows him back home in the Macedonian countryside, which is where the film began.

Kirkov is an ethnic Macedonian of Orthodox Christian heritage, though he pretty clearly doesn’t practice the faith. In the film’s beginning, a lakeside (presumably Lake Ohrid) Orthodox monastery is an occasional place of refuge for Albanian Muslims fleeing Christian persecution. We learn that ethnic and religious tensions between Albanian Muslims and Christian Macedonians are ramping up, and have become violent. In the first section, the monks have (unwittingly, for most of them) given shelter to an Albanian girl from a nearby village. So strong is the ethnic hatred that when Christian men come looking for her, they pay little respect to the authority of the abbot or the sanctity of the monastery. They just want to kill.

But they are not alone. As we will learn before this section ends, their Albanian enemies — until recently, seen as neighbors — are so drunk with ethnic pride and hatred that they violate other sacred boundaries in asserting the tribe’s prerogatives.

Kirkov comes from this region. We meet him in the film’s second part. He has been in Bosnia documenting the civil war there, and explains to Anne, his editor (and lover), how by simply doing his job, he inadvertently became responsible for the death of an innocent. Filled with guilt and disgust over man’s inhumanity to man, he decides to quit the business, and invited Anne to leave with him for Macedonia.

There is the matter of her husband, to whom she is estranged. They meet over dinner to talk things over. The viewer can tell why Anne might have been drawn to the burly, strong-feeling Aleksandr, and away from her relatively milquetoast English husband. Doesn’t make it right, but you can see how it might have happened. We are given to understand that the repressed Oxford-trained woman is irresistibly drawn to wildness. During her anxious dinner with her husband, there is an outbreak of serious violence in the restaurant that appears to have something to do with a feud between Balkan immigrants. The point seems to be: if you welcome immigrants into your society, do not be surprised when their own blood feuds and barbaric ways play out on your own streets.

Note well, though, that writer-director Milcho Manchevski’s 1994 screenplay delicately points out that the British too have their own ethno-religious dispute that erupts into daily life: the Northern Irish problem. When a character makes a crack about the violent Balkan patron and waiter, saying that “at least they’re not from Ulster,” the restaurant owner, a man of almost comic sophistication, politely points out that he himself is an Ulsterman.

With Anne back in London making up her mind, Aleksandr returns to his home village. When he last lived there, it was part of Yugoslavia, and governed by Titoist communism. Ethnic Albanians and Macedonians went to school together. Things have changed greatly in his absence. Old hatreds have reappeared. It has become the kind of place where an angry character taunts Aleksandr to take up a rifle, and avenge “five hundred years of your blood.” (Under Ottoman Turk rule, Albanian Muslims enjoyed many privileges over the oppressed Christian masses.)

Aleksandr wants no part of it. In fact, he wants to stand against it. But can he?

Much turns on a line heard more than once early in the film: “Time never dies. The circle is not round.” This mysterious remark is key to the film’s moral. While it is true that violence and hatred are inescapably part of the human condition, we are not condemned to live them out. Yes, events recur, but the existence of time means that they are more like a spiral than a circle. If we choose life, if we choose goodness, we break the repetitive circle — not permanently (something that will not happen this side of the Second Coming), but we may make it less likely that our children will suffer the same fate. In this sense, Before The Rain is a more or less conventional anti-war film.

But things get messier in Anna’s second reading. Aleksandr has come out of a traditional culture, one that still lives by the old ways, and has found success in a liberal, First World culture that has for the most part put religion and ethnicity behind. In fact, he makes his living observing the poisoned fruits of that world (generally speaking), and selling those images to people who live in the liberal world, which has honored him (e.g., Pulitzer Prize) for his work. It was when his work as an observer broke the invisible wall, implicating Aleksandr in the violence, that he renounced his work and sought to return to his home village.

The silence of the monastery, where the only things heard are Scripture, sung prayers and Psalms, and the occasional words among the monks, keep it as a sort of paradise free from the wild passions consuming those outside its walls. Early on, when the angry search party of Christians comes looking for the Muslim girl, the abbot tells the search leader that the monastery has served as a place of refuge for Bosnian Muslim refugees, because all are the same in God’s eyes. No Muslims are there now (as far as the abbot knows), but the abbot does not apologize for what they have done. The Christian thugs love the sound of gunshots and the sonic violence of hip-hop music: in this film, these are signs of the modern world. One of the Christian thugs literally cannot stand silence, and it renders him beastly and insensate.

When the film’s narrative shifts to London, we hear the same kind of soundscape. In one of the opening scenes in London, a young man who is a messenger for the photo editor Anne talks to her dreamily of drugs and music and sex. He looks at a photographic image of Madonna (!), breasts showing and dressed like a dominatrix (this was her “Sex” period), and is overcome by a vision of Paradise in which the entire world is pulsing with pagan sexual energy. “Just imagine, someone out there‘s shagging right this very second,” he says. It is a remarkable image of worldly corruption. Online, I stumbled across this paper about “listening” in Before The Rain. Excerpt:

The Orthodox monastery and church on Lake Ohrid (composed of several actual settings but presented as one location in the film), is itself a place quite “unreal, closer to a mythical land than to current-day Macedonia.” With its profound silences, this setting creates a unique environment in which one can hear properly. The classic Greeks distinguished sigaô, denoting a general absence of sound, from siôpaô, referring to the absence of human speech. Adjusting these terms to modern times, it becomes apparent that the monastery creates both sigaô, the absence of the intrusive noise of modern life (traffic, industry, machines, media), and siôpaô, the absence of verbal noise. Situated in a breathtaking but rugged terrain accessible only by foot, the monastery offers the silencing of the modern world’s noisy everyday life and its multiple voices and demands for attention, or, in other words, a reclaiming of that silence which has “today . . . become an endangered species,” as contemporary acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton puts it. In terms of the verbal noise or, as Corradi Fiumara calls it, the “environmental degradation . . . with regard to the world of language,” that is, “an unmonitored saturation of written or spoken words and . . . a concomitant lack of silence,” the complete absence of things such as electronic media allows the creation of siôpaô, or the silencing of this endlessly proliferating “saturation of words.”

The author of the paper, Gordana P. Crnkovic, observes that the thuggish Macedonian Christian brutes are listening to the same violent hip-hop song that passing teenagers in London are. She writes that there is a “connection by noise” to the modern world in London, and the largely pre-modern world of the Balkans. The only place in the film where one can escape modernity and find silence is the monastery. If you plan on seeing the movie, do not read Crnkovic’s paper in advance, as it is full of spoilers. She does point out that the young monk Kiril, who is at the center of Part I, does not speak a word of Albanian, and is himself two years into a vow of silence. But his dwelling in the soundscape of the monastery has taught him to “listen” such that he knows that he has a Christian responsibility to shield the hunted Muslim girl, though he cannot speak her language. My kids and I are all home sick from the Liturgy today, but earlier this morning, I was reading to them from today’s Scripture reading. I ended up talking to them about the reading, and telling them how our culture today is so full of lies and confusion. Always return to Scripture and the Church, I told them, to know what is real. Writing this post and reconsidering the film, which I saw last night, brings that point home powerfully.

So, this is the world to which Aleksandr returns. In London, he seemed to believe he could return home and live a quiet life without taking sides. “I don‘t want to be on the same side with any of them,” he tells Anne. “Brainless mongoloids butchering each other for no reason.” This is an illusion, an illusion that his British passport and his life lived in the West has allowed him to cultivate. Back home, the clan and the tribe rule, not individuals. That is a Western thing. Aleksandr’s imagination was formed in the Tito era, when tribe and clan and religious identity were suppressed. Now, with the passing of communism, they have come roaring back, but Aleks is ill-equipped to survive in this world.

Reader Anna, recall, wrote of the film that:

a deeper understanding points to seeing the difference between East and West, tradition and modernity, and why it has become nearly impossible to live in either.

In my interpretation, it is nearly impossible for Anne and her English husband to live in modernity, because she lacks rootedness (Anne blames her husband for their unhappy marriage, but her mother says no, dear, the problem is you), and because she lives in a world of busy-ness, such that she has no inner peace within which she might deal with her passions productively. Again, you can see why the “noise” of the rugged, masculine war photographer’s life appeals to her. It speaks to an inner fantasy she has of living a life of passion, not the settled, urban, modern life that she has in London. The images she processes as part of her job — shots of war, but also of sexual passion — call to her. The vulgar messenger invites her to go to the Glastonbury festival with him, for a veritable orgy of drugs, music, and sexual excess. You can tell that she wants to do this, but will not allow herself. To see her sympathetically, one can imagine the difficulty of living such a hollow life, one in which her restlessness is unsatisfied. That restlessness is part of what makes her human — but as a modern, she has no way to connect it to transcendence, which would order it. Aleks invites her to go live a relatively primitive life with him in rural Macedonia — something that tempts her, because it seems to her more “real” than the rarefied cosmopolitan but dull life she has in London.

Of course it is impossible for Aleks (and Anne) to live in the premodern Balkans, because their modernity would not allow them to escape the destructive historical passions of the village. Aleks is tied to many of these people by blood, and blood carries obligations with it. Nor, we see, are the Albanian Muslims in the neighboring village immune to these forces. The Old World, so to speak, really is one of much more intense passions and drama than what Anne and Aleks could have had back in London … but the shadow side of all that premodern, or anti-modern, “authenticity” is very black indeed.

Anne and Aleks are victims of their poetic imagination, thinking that it is possible to live as observers (literally or figuratively) without being involved. This is their tragedy. In fact, the dissolution of Anne’s marriage comes from her inability to commit herself to the man who is actually her husband. In a sense, she wishes to be an “observer” of their marriage: in it, but not of it. This is not possible, though. On the other hand, she balks when Aleks asks her to commit to him in Macedonia. Anne desires more than modern life gives her, but she will only be satisfied with total commitment — something that she cannot bring herself to give.

Aleks, again, is a man of passion and commitment, willing to risk his own life for his art, as he has proved again and again. Now he’s willing to sacrifice his art for the sake of life. He has discovered that it is impossible to be a mere observer, that simply by recording what you see, you become part of it. The murderous violence taints him. He has this idea that if he goes back to the village, he will return to some kind of childhood innocence. Even though he surely knows better, this is the craving that drives him.

To Anna’s point, it is remarkable how globalization has brought aspects of Western culture to this remote Balkan village (the popular music, the children’s chatter featuring Western pop culture icons), but also the violence and atavistic passions of the Balkans to the West. You can’t escape modernity, nor can you escape pre-modernity. I need to think more about the role of the monastery in the film. The holy iconography on the wall makes sacred art of human history and passion, even violent passion (none more violent than the murder of God Himself by men). Yet the monks themselves aren’t fully removed from time and passion. They wish to be neutral in the conflict between Muslims and Christians, but they aren’t allowed to be, in the end — and the first section of the film concludes with an act by the abbot that is highly questionable, though his motivation is in question.

Before The Rain doesn’t offer a solution to the problem of war and violence, but it does offer strong commentary on nature of that problem, as it manifests in our own time and place, and on false solutions. It does, however, tell us that we are not fated to relive these conflicts — that they are perpetuated by human choice. I am interested in the role that religion — the Christian religion specifically — might play in breaking the circle of violence, by drawing violence into itself, and releasing it through Christ’s sacrifice. The late René Girard’s theory of mimesis is important here. Excerpt from a primer on it:

Mimetic theory explains the role of violence in human culture using imitation as a starting point. “Mimetic” is the Greek word for imitation and René Girard, the man who proposed the theory over 50 years ago, chose to use it because he wanted to suggest something more than exact duplication. This is because our mimeticism is a complex phenomenon. Human imitation is not static but leads to escalation and is the starting point for innovation. Girard’s great insight was that imitation is the source of rivalry and conflict that threatens to destroy communities from within. Because we learn everything through imitation, including what to desire, our shared desires can lead us into conflict. As we compete to possess the object we all want, conflict can lead to violence if the object cannot be shared, or more likely, if we refuse to share it with our rivals.

Girard believes that early in human evolution, we learned to control internal conflict by projecting our violence outside the community onto a scapegoat. It was so effective that we have continued to use scapegoating to control violence ever since. The successful use of a scapegoat depends on the community’s belief that they have found the cause and cure of their troubles in this “enemy”. Once the enemy is destroyed or expelled, a community does experience a sense of relief and calm is restored. But the calm is temporary since the scapegoat was not really the cause or the cure of the conflict that led to his expulsion. When imitation leads once again to internal conflict which inevitably escalates into violence, human communities will find another scapegoat and repeat the process all over again.

By reading ancient myths Girard realized that ancient sacrificial religions originated in a community’s attempt to ritualize the scapegoating cure. Prohibitions forbade the mimetic envy and rivalry that lead to conflict; ritual sacrifices recreated the expulsion or death of the scapegoat. By reading the Bible, Girard realized that the Judeo-Christian tradition reveals the innocence of the scapegoat and so renders ancient religion ineffective. The last 2,000 years is witness to humanity’s attempt to find non-sacrificial ways to control our rivalry and conflict. Christian apocalyptic literature predicts our failure to do so. Finding ways to form unity and ease conflict without the use of scapegoats is thus the key to establishing a real and lasting peace.

More:

Q. What role did scapegoating play in ancient sacrificial religions?

A. Girard hypothesizes that the spontaneous phenomenon of scapegoating occurred over and over in early proto-human groups and was eventually ritualized into ancient sacrificial practices. This use of ritualized scapegoating to control conflict and establish unity is what made culture possible. Often it is believed that ancient religions arose out of mistaken or delusional thinking and were unnecessary add-ons to human evolution. Girard believes the opposite: ancient sacrificial religions were incredibly reasonable and realistic and absolutely essential to human development. Without peace and unity, no community can accomplish anything; they disintegrate before they can innovate. And peace and unity is exactly what the ancient sacrificial practices provided.

Scapegoating is also the origin of the apparently contradictory nature of the ancient gods who often represent both good and evil qualities in one divinity. This makes sense once you realize that after the elimination of the scapegoat (ritualized into sacrifice), the scapegoat is miraculously discovered to be a divinity who restores order and peace. The gods thus represent the principle of order and disorder, a principle that controls outbreaks of violence within the community by executing a small does of violence against an isolated victim or victim group.

Q. What is myth?

A. Modern scholars tend to think that myths are completely imaginary, fabricated stories that arose out of the primitive mind of early man. Often it is thought that myths came first and then rituals and sacrificial practices evolved out of these stories. For Girard, it is always the reality of spontaneous scapegoating violence which comes first. This violence brings peace to a conflicted community and over time rituals which repeat the violence against the scapegoat in a controlled form emerge as preventive measures against the return of the violence. Myths are the stories told by the community to justify its use of ritual violence against the victim.

The purpose of myth is to conceal the truth of the innocence of the sacrificial victim, because in order for the sacrifice to be effective the community must believe in the guilt of the victim (just as it did when the scapegoating occurred spontaneously), Therefore, myth places blame solely on the victim, siding with the community, or crowd. Myth further justifies itself by demonizing the victim as the sole source of the contagious violence and disorder within the community. Thus for Girard myth is at best only half the story: the community does indeed experience a sense of relief and restoration of peace when the victim is sacrificed. But myth also conceals the deeper truth that the victim was arbitrarily chosen, innocent of the community’s problems, and wrongly executed.

Q. Is Christianity an example of a myth?

A. Christianity is often critiqued as simply an example of another ancient myth that involves a dying and rising god. For Girard, however, it is Christianity which destroys the power of myth to conceal the innocence of the victim. In the Christian narrative, the victim of the crowd’s violence is innocent, falsely accused by both religious and secular authorities, and put to death in the most shameful of circumstances. There is no duality within Christ as there is with the gods of myths: Jesus is not portrayed as the cause of the community’s problems, but always portrayed as innocent despite the accusations against him. Girard has famously said that the secret heart of the sacred is violence itself. He has also said that the Christian gospel reveals is that the secret heart of God is non-violent, self-giving unto death. Quite a contrast!

Read the whole thing. Girard was a convinced Catholic, though I have no idea what the convictions are of the people who wrote that primer.

I don’t know to what extent the filmmaker sees Orthodox Christianity as offering a way out of the circle of violence, or as offering some sort of illusion of hope. Several times we hear the wild Balkan men proclaiming the “eye for an eye” ethic — which Jesus explicitly repudiated (but which Donald Trump proclaimed was the most meaningful part of the Bible to himself; so much for the “barbarians” being confined to the hills of the Balkans!). True, the monastery in the film was a place of peace, and the monks courageously offered refuge to Muslims fleeing Bosnian violence. But the act of the abbot towards the end of Part I makes one wonder whether or not local politics affected his vision, or if there is something else blinding his moral vision. Whatever the truth, the abbot fails to live up to his stated beliefs, which is a sign to us that even the best among us may fall.

More to Girard’s point, the role of iconography in Orthodox Christianity may be compared to the role Aleksandar plays as a war photographer. He wishes to bear witness through his photographs to the inhumanity of war. It is only when by accident his attempt to be an observer causes someone to die that he leaves his profession, feeling tainted by murder. What about the iconographer, and those whose faith is illumined and shaped by iconic images (in the church and monastery) of violence? Do the images help us to refuse violence — or do they in some sense sacralize it? This is an open question in the film, I think. I know how I, as an Orthodox Christian, answer that question, but then again, I was not raised with them, as Orthodox peoples in the Balkans were.

Incidentally, there’s a scene early in Part II in which Anne walks by a church in London and peeks in on a boy’s choir singing a prayer in Latin. It’s a startling contrast to the rich, deeply masculine chants of the Orthodox East. I don’t think the director is faulting Catholicism or Anglicanism, but is rather illustrating how in Western Europe, Christianity and its chants have become a feminized, aestheticized phenomenon, as opposed to the Christian East. On the other hand, in the post-Christian West, one doesn’t find blood feuds, or cases in which Christian men storm around with guns demanding “an eye for an eye.” There’s a paradox there. Yet Anne, living in this peaceful modern setting, finds it altogether sterile and unsatisfying. She reminds me of the decadent, exhausted sophisticates in Cavafy’s poem “Waiting For The Barbarians”. For Anne, Aleks and his people are “a kind of solution.”

Enough from me. Let’s hear what you think. I’m especially eager to hear from Anna in Budapest, who I thank heartily for recommending this film to me.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers