Rod Dreher's Blog, page 481

March 5, 2017

Books For Small-O Orthodox Christians

I am very, very grateful to Father Dwight Longenecker for his generous review of The Benedict Option — and for pairing it with Anthony Esolen’s great book Out Of The Ashes.

What is the answer? If both men call first for an awareness of the problem, they also call for a conscious, intentional, and disciplined response. Mr. Esolen’s solutions are broader in their intent—with particular examples, whereas Mr. Dreher’s solutions are more specific. In The Benedict Option he lays out particular actions that individuals, families and communities can take. Both men acknowledge that the vocation to re-build a Christian culture will require hard work, sacrifice and serious commitment.

Mr. Dreher is to be commended too, for acknowledging the shared worldview of all Christians who are committed to historic Christianity. Increasingly the division in Christendom is not between Protestant, Catholic or Eastern Orthodox. The division is between those who believe Christianity is revealed by God and is eternally true, and those who believe the Christian religion is a human construct and a historical accident which not only can be adapted for every age, but must be.

When he emerged from his prison cell in communist Romania, Baptist pastor Richard Wurmbrand said in the torture chambers there were no Baptists, Catholics or Orthodox. There were only brothers in Christ. This is the ecumenism of our age: Evangelicals, Catholics and Orthodox who hold to the timeless truths of Scripture and the Christian tradition will know at heart that they are brothers and sisters. Together they will rediscover the foundations of the faith, and almost despite themselves, may lay the foundation for a new Christendom.

If you’re interested in the Ben Op, please do order Esolen’s new book, as well as Archbishop Charles Chaput’s latest, Stranger In A Strange Land. We are all three talking about how to be authentically Christian, and to build an authentically Christian culture, in post-Christian America. These men are Roman Catholic, and I am Eastern Orthodox, but all three books will be helpful to all small-o orthodox Christians, as defined by Father Dwight’s quoted remark above.

March 4, 2017

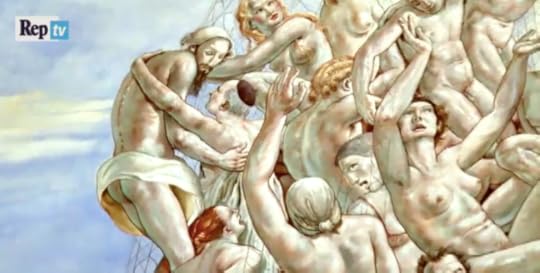

Archbishop Paglia’s Homoerotic Fresco

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, who commissioned the homoerotic fresco, is pictured in the skullcap (Screenshot from La Repubblica video)

The archbishop now at the helm of the Pontifical Academy for Life paid a homosexual artist to paint a blasphemous homoerotic mural in his cathedral church in 2007. The mural includes an image of the archbishop himself.

The archbishop, Vincenzo Paglia, was also recently appointed by Pope Francis as president of the Pontifical Pope John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family.

The massive mural still covers the opposite side of the facade of the cathedral church of the Diocese of Terni-Narni-Amelia. It depicts Jesus carrying nets to heaven filled with naked and semi-nude homosexuals, transsexuals, prostitutes, and drug dealers, jumbled together in erotic interactions.

The story, from the Catholic Lifesite News, features photographs of the mural. You can see a lot more in the original piece from Repubblica, a left-wing newspaper and Italy’s second-largest.

And the left loves to say that conservative Christians are obsessed with homosexuality. More from the story:

According to the artist, a homosexual Argentinean named Ricardo Cinalli who is known for his paintings of male bodies, Bishop Paglia selected him out of a list of ten internationally-known artists specifically for the task of painting the inner wall of the facade. Bishop Paglia, along with one Fr. Fabio Leonardis, oversaw every detail of Cinalli’s work, according to Cinalli, who approvingly notes that Paglia never asked him if he believed in the Christian doctrine of salvation.

“Working with him was humanly and professionally fantastic,” Cinalli told the Italian newspaper La Repubblica in March of last year. “Never, in four months, during which we saw each other almost three times each week, did Paglia ever ask me if I believed in salvation. He never placed me in an uncomfortable position.”

“There was no detail that was done freely, at random,” added Cinalli. “Everything was analyzed. Everything was discussed. They never allowed me to work on my own.”

More:

In August of last year, Pope Francis moved Paglia from the Pontifical Council for the Family to the presidency of the Pontifical Academy for Life, as well as of the Pontifical Pope John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family, two organizations founded by Pope St. John Paul II to defend the sanctity of human life and family values. Soon it became apparent that the Academy was being radically transformed when new statutes were issued that no longer required members to sign a declaration of fidelity to the Catholic Church’s perennial teachings on the right to life. On February 17, it was confirmed that all Academy memberships had been terminated, leaving only Paglia and his staff at the top of an otherwise empty organization.

And yet, somehow, Cardinal Burke and the “rigid” members of the laity are the problem.

Missing The Point Of The Benedict Option

Christianity Today generously published an adaptation of The Benedict Option as its cover story this month. You can read it here. The magazine asked four prominent Evangelicals to respond to it. You can read their short contributions here.

I’m going to respond to some of what each has to say below, but before I do, let me say that I assume that none were able to read the entire book — that they’re responding to the adaptation that appeared in the magazine. It would be unfair of me to hold them responsible for things they got wrong, or distorted, if they haven’t seen the entire book, and I apologize in advance if below I inadvertently fault them for something they were not in a position to know. I’m responding because I don’t want those who read the symposium think that the writers have accurately described my book, but at the same time I assume the good faith of all four respondents.

With that caveat in place, here are a few thoughts from me.

David Fitch frames the Benedict Option as a choice between full withdrawal from social life or engagement — and says the Gospel requires us to choose the latter:

We cannot however, make a choice between living in Christian community or being present in our culture. To paraphrase theologian Stanley Hauerwas, how can the church possibly withdraw when by necessity we find ourselves surrounded? There’s no place to go.

The church is made who it is by being the church in the world. The church’s primary reason for being is to be in and among (but not of) the world (John 17:14–15). Just as Israel was birthed to be a blessing to the nations (Gen. 22:18), so also the church was sent by the Spirit into the world to bring all the nations to himself (Matt. 28:19).

We cannot, therefore, extract ourselves from the world without losing who we are. The church does not have a mission. It is mission.

Fitch says that I pose a “false dichotomy,” but the fault is actually his. His response seems to be another example of people imposing their own fears on the Benedict Option. There is nothing in the CT cover story that advocates bunkering down in our own neo-Amish enclaves. Seriously, read it for yourself. As I have said repeatedly elsewhere (and again, to be fair, without having read the entire book, Fitch may not know this), total withdrawal is neither possible nor desirable. As I write in The Benedict Option:

This is not just about our own survival. If we are going to be for the world as Christ meant for us to be, we are going to have to spend more time away from the world, in deep prayer and substantial spiritual training—just as Jesus retreated to the desert to pray before ministering to the people. We cannot give the world what we do not have. If Israel had been assimilated by the world of the ancient Near East, it would have ceased being a light to the world. So it is with the church.

I don’t know David Fitch, who is a seminary professor, but I doubt he would disagree with that. I would challenge him to consider, though, the extent to which the church, its institutions, and its families are preparing people to witness to the world we actually live in — and that includes being discipled morally and spiritually such that we can be in the world without being assimilated into it. There is ample evidence that we are failing, and failing badly. Sociologist Christian Smith has written several books about this, based on his own research. He is not alone.

Over and over as I travel to Christian college campuses, I hear the same refrain from professors: these are great kids, but they come to us knowing next to nothing about the Christian faith. We’re not talking only about information concerning the Christian faith (though that too is an enormous problem). We’re talking about formation in the Christian faith, which is to say the practices, the way of life that forms stout and resilient Christian hearts.

I recently spoke with an Evangelical pastor who works with young men preparing for seminary. Keep in mind these are men who love Christ so much that they are planning to spend their entire lives serving Him and His people in ministry. And yet, said the pastor, every single one of them has an addiction to pornography. The pastor has concluded that the church is terribly naive about the relationship between its people and technology. He’s right. So many conservative Christians hand their pre-teen kids, or young teenagers, smartphones, and hope for the best. This is crazy! It is unreasonable to expect pubescent boys in particular to be able to control their desire for sexual images. They need help from parents and from their Christian community. They need for us to shield them while we build within them the capacity of character that will allow them to say no to it when they are older. And not only boys: one college professor told me that he’s observed the male students in his classes struggling against porn, but recently, for the first time ever, he’s starting to see his female students doing the same.

Yet many of us sit in judgment over the unbelievers in the world. I spoke with a Christian who sends his kids to public school. His son plays with a Christian kid in the neighborhood whose parents homeschool. The Christian man’s son came home from the homeschooled boy’s house and said, “Guess what I saw today at [name’s] house on a tablet?” It was pornography, of course. Said this father, “And we’re the bad parents who put our kids in the public school, where they’re supposedly exposed to all this stuff?”

That father is correct. So often we conservative Christians are quick to make judgments about the rest of the world, without picking the tablets and smartphones logs out of our own eyes.

We in the church are failing terribly at formation — and, mind you, porn is only one area. Smith and his team found that only nine percent of Christian Millennials said that they see materialism and consumerism as a spiritual and moral problem against which they should struggle as believers. Whatever we are doing to form the next generations, it’s not working. The evidence is right in front of our eyes, if we care to see it. Hear me clearly: we must stay engaged with the world for the sake of mission, and fulfilling the Great Commission. But we cannot give the world what we do not have.

I don’t have any serious objections to law professor John Inazu’s take, though I suspect that the things that most concern him about the CT article are answered in the book in a way that allays some of his worries about the Benedict Option. One thing in his short response jumped out at me:

Tim Keller and I have argued that our confidence in the gospel lets us find common ground with others even when we can’t agree on a common good. This confidence in our own beliefs and the institutions that sustain them is also what I’ve suggested allows Christians to pursue confident pluralism.

I agree with this. We conservative Christians live in a pluralistic world, whether we like it or not, and we have to learn how to relate to it. I take God’s instruction to the Hebrew exiles in Babylon, as spoken through the prophet Jeremiah (Jer. 29), to be prescriptive for Christians today: plant yourselves among the unbelievers, raise your families, pray and work for the prosperity of the whole — but do not allow yourselves to be assimilated to their false gods. My argument in The Benedict Option is that very many American Christians today lack confidence in our own beliefs and institutions, and moreover, don’t really know what those beliefs are supposed to be or what they require of us in this extraordinary time and place. Nor do our institutions. We have to reform — individually, in our families, in our churches, and in our institutions — if we are going to form the kind of believers who are capable of engaging in “confident pluralism” without being assimilated to the strange gods of 21st century America.

I’m not quite sure what Karen Ellis’s objections are in her piece. She starts like this:

The impulse of some in the church to focus inward is admirable on the surface. A desire for more robust communities committed to prayer, discipline, study, obedience, and being the church without compromise and at cost, are key to surviving a chilly—and sometimes hostile—cultural climate.

Yet as an advocate for the 250 million global Christians currently living under various levels of hostility, I’ve observed that inward focus is not where New Testament community ends.

And then she goes on to cite various communities who are, in fact, living out the Benedict Option in intense and self-sacrificial ways. Hey, I applaud and encourage those Christians! There is nothing in the Benedict Option that says otherwise. The Ben Op says, however, that if the church wants to produce men and women capable of living those kinds of lives, whether in inner cities, suburbs, small towns, or wherever, it is going to have to work a lot harder on formation and discipleship. My sense reading Ellis’s bit is that she was reacting to what she imagines the Benedict Option to be rather than the thing I actually describe. This is a very common response from Evangelicals, many of whom, no matter how many times I say otherwise, assume that I’m saying that we have to run for the hills and build high, impenetrable walls between ourselves and the world. In truth, I am saying that if you want to present the true face of Christ to the outside world, you have to do much more in the way of prayer, contemplation, and discipled living inside the family, the congregation, and in Christian schools.

Why this is controversial eludes me.

Finally, Hannah Anderson says — wait for it — that the Benedict Option is not something for Evangelicals because it calls on Christians to head for the hills and build high, impenetrable walls between themselves and the world:

Rod Dreher’s call for a tactical retreat to resist secularism may be a viable corrective for Christian faith traditions with a well-established understanding of corporate faith and the role Christianity plays in the common good. But for evangelicals, whose theology emphasizes the individual’s relationship with God, retreat could actually exacerbate our individualism by disabling a key piece of our systematic: the call to actively and intentionally work for the good of our neighbor’s soul.

The. Benedict. Option. Does. Not. Call. For. This.

More Anderson:

Historically, evangelicalism’s individualistic focus has been held in tension by our commitment to the Great Commission. If every individual must answer to God, we must be about the business of evangelizing and discipling every individual. From this shared mission sprang communal institutions: schools, mission societies, local churches, and mercy ministries. For evangelicals, building community must be a form of advance, not retreat.

The point of the Benedict Option is that if the Kingdom is going to advance, we have to undertake a strategic retreat — not wholesale retreat, but strategic retreat — for the sake of strengthening our witness. Take one step back to prepare ourselves to take three steps forward. For Anderson, I’d like to share this good news, from a conversation I had with a monk, recounted in The Benedict Option:

The power of popular culture is so overwhelming that faithful orthodox Christians often feel the need to retreat behind defensive lines. But Brother Ignatius warned that Christians must not become so anxious and fearful that they cease to share the Good News, in word and deed, with a world held captive by hatred and darkness. It is prudent to draw reasonable boundaries, but we have to take care not to be like the unfaithful servant in the Parable of the Talents, who was punished by his master for his poor, fearful stewardship of the master’s property.

“The best defense is offense. You defend by attacking,” Brother Ignatius said. “Let’s attack by expanding God’s kingdom—first in our hearts, then in our own families, and then in the world. Yes, have to have borders, but our duty is not to let the borders stay there. We have to push outward, infinitely.”

Again, I presume the good faith of these critics, who were responding to a portion of the book, not the whole thing. I do hope they will read the book when it comes out on March 14, and rethink their reactions. They will no doubt find things in it to criticize — I would be surprised if every reader agrees with everything I’ve written — but at least they will be criticizing from a more informed position. Let me encourage potential readers, Evangelical and otherwise, to check the book out for yourselves, and not to rely fully on the reactions of others.

UPDATE: This comment from Father Lawrence Farley, in Canada, seems to me really insightful:

Since my life and experience all come from north of the 49th parallel I don’t know how accurate any of my observations might be about American Christianity. It does seem to me, however, that your book is drawing rather a lot of fire before it has even come out, and I have a guess as to why this might be. It seems as if many of your reviewers cannot resist embracing a dichotomy of what you describe as “full withdrawal from social life or engagement” as if these were the only two available options, and then inevitably reading your book as counselling the former. My guess is that American Christianity has always been about cultural power and ascendency– e.g. which groups are invited to National Prayer Breakfasts– and that the current ouster from cultural ascendency is too difficult to bear. The prediction of the late RC bishop of Chicago Francis George about dying in bed and his successor dying in prison and his successor after that dying as a martyr in the public square strikes at the heart of their self-understanding of what American Christianity is about. American Christianity by definition retains its place in the sun. Your book is offensive because it denies this basic principle, and the reviewers respond by reading into it the only alternative to cultural ascendency they know– namely full withdrawal, as if Ben-Op Christians were Orthodox Amish in their bomb shelters. That is not what the book counsels, but for them that is the only alternative to cultural ascendancy, so that must be what you said. If it’s any consolation, there is probably nothing you could have added to the book which would have made a difference in how they viewed it. Protesting that you are not in fact counselling total withdrawal would only have provoked the accusation that the book was self-contradictory. Forgive me if I am too harsh in my view of American Christianity, but that’s how it looks to me in the Great White North.

March 3, 2017

On The Ignatius Trail

Area Fathead and his Spiritual Advisor

From The Fifth Gospel A Confederacy Of Dunces:

He sat at attention in the darkness of the Prytania only a few rows from the screen, his body filling the seat and protruding into the two adjoining ones. On the seat to his right he had stationed his overcoat, three Milky Ways, and two auxiliary bags of popcorn, the bags neatly rolled at the top to keep the popcorn warm and crisp. Ignatius ate his current popcorn and stared raptly at the previews of coming attractions. One of the films looked bad enough, he thought, to bring him back to the Prytania in a few days. Then the screen glowed in bright, wide technicolor, the lion roared, and the title of the excess flashed on the screen before his miraculous blue and yellow eyes. His face froze and his popcorn bag began to shake. Upon entering the theater, he had carefully buttoned the two earflaps to the top of his cap, and now the strident score of the musical assaulted his naked ears from a variety of speakers. He listened to the music, detecting two popular songs which he particularly disliked, and scrutinized the credits closely to find any names of performers who normally nauseated him.

…

He put the empty popcorn bag to his full lips, inflated it and waited, his eyes gleaming with reflected technicolor…In the darkness two trembling hands met violently. The popcorn bag exploded with a bang. The children shrieked.

“What’s all that noise?” the woman at the candy counter asked the manager.

“He’s here tonight,” the manager told her, pointing across the theater to the hulking silhouette at the bottom of the screen. The manager walked down the aisle to the front rows, where the shrieking was growing wilder. Their fear having dissipated itself, the children were holding a competition of shrieking. Ignatius listened to the bloodcurdling little trebles and giggles and gloated in his dark lair. With a few mild threats, the manager quieted the front rows and then glanced down in the row in which the isolated figure of Ignatius rose like some great monster among the little heads.

…

“Oh my goodness!” Ignatius shouted, unable to contain himself any longer…“What degenerate produced this abortion?”

“Shut up,” someone shouted behind him.

…

When a love scene appeared to be developing, he bounded up out of his seat and stomped up the aisle to the candy counter for more popcorn, but as he returned to his seat, the two pink figures were just preparing to kiss.

“They probably have halitosis,” Ignatius announced over the heads of the children. “I hate to think of the obscene places that those mouths have doubtlessly been before!”

“You’ll have to do something,” the candy woman told the manager laconically. “He’s worse than ever tonight.”

The manager sighed and started dow the aisle to where Ignatius was mumbling, “Oh, my God, their tongues are all over each other’s capped and rotting teeth.”

Standing outside the Prytania today, in my heart, I raised a goblet of Champipple to the memory of Redd Foxx and John Kennedy Toole. And how was your day?

‘Apocalypse? Wow!’

If you’re sick of all the Benedict Option material on this blog, well, I’m sorry. You’re just going to have to hold your nose for the next two or three weeks. The book will be out on March 14, and already the reaction is starting to come in. I’m not going to be able to answer every critic of the Benedict Option, nor will I be able to answer critics as completely as I might like. But at this point, 11 days from publication, I have a little breathing room to answer a few, at least in part. Let me start by thanking everyone who read my book and wrote something about it, however critical. I appreciate it sincerely.

Note well that I’m not going to respond to positive things these critics may have said about the book, only the negative things.

I’ll start today with Evangelical writer Katelyn Beaty’s take in the Washington Post. Excerpt:

On the national level, at least, the political engagement Dreher advocates for extends primarily to the concerns of conservative Christians. He is pessimistic about such Christians having much influence in Washington and despairs that Washington politics can stop America from sliding farther into post-Christian decadence. Yet he insists that conservative Christians must keep defending religious liberty. Religious liberty here is framed as important insofar as it lets traditional Christians be traditional Christians, not because it’s core to American democracy or because Muslims, say, deserve the same freedom as Christians to practice their faith in peace.

Well, the audience for this book is conservative Christians. I’m pleased to have all kinds of readers, but the people to whom I’m speaking in this book are conservative Christians — or, as I prefer to call them (because it lacks the political connotation), small-o orthodox Christians. As I say at the start of the Politics chapter, our tribe has been far too quick over the past few decades to trust in partisan politics (specifically, partisan Republican politics). The book is by a theologically and culturally conservative Christian, for theologically and culturally conservative Christians.

I believe that religious liberty is important for a number of reasons, but I’m trying to get the conservative Christians who read The Benedict Option to understand that if our religious liberty is constricted or even taken away, we stand to lose the most precious of our freedoms. As I make clear in the book through interviews with law professors, religious liberty activists, and others, this is not at all an abstract threat. Yet a shocking number of conservative Christians don’t understand what’s happening, or what’s at risk. The Benedict Option is not a book about the glories of religious liberty in America — that would be a different book, one I would heartily endorse — but specifically speaks to a particular group of Christians about the most important issue facing us. As I write in the book:

Religious liberty is critically important to the Benedict Option. Without a robust and successful defense of First Amendment protections, Christians will not be able to build the communal institutions that are vital to maintaining our identity and values.

But not only religious liberty. When someone says that Dreher advocates Christian quietism and withdrawal from the public square, show them this passage from The Benedict Option:

To be sure, Christians cannot afford to vacate the public square entirely. The church must not shrink from its responsibility to pray for political leaders and to speak prophetically to them. Christian concern does not end with fighting abortion and with protecting religious liberty and the traditional family. For example, the new populism on the right may give traditionalist Christians the opportunity to shape a new GOP that on economic issues is about solidarity more with Main Street than Wall Street. Conservative Christians can and should continue working with liberals to fight sex trafficking, poverty, AIDS, and the like.

The real question facing us is not whether to quit politics entirely, but how to exercise political power prudently, especially in an unstable political culture. When is it cowardly not to cooperate with secular politicians out of an exaggerated fear of impurity—and when is it corrupting to be complicit? Donald Trump tore up the political rule book in every way. Faithful conservative Christians cannot rely unreflectively on habits learned over the past thirty years of political engagement. The times require much more wisdom and subtlety for those believers entering the political fray.

These are not the words of someone who believes that the only reason for Christians to stay involved in politics is to fight for religious liberty. I say that religious liberty is the most important political cause to which conservative Christians should devote their time, passion, and resources. Why? Hang on for a second, and I’ll tell you.

More Beaty:

Meanwhile, Dreher overlooks the importance of Christians working in mediating institutions that protect the most vulnerable from being crushed by violence or greed. Take groups such as World Relief, an evangelical relief agency that has resettled more than a quarter million refugees in the United States since 1975. Most of the refugees are women and children who have uprooted their lives to flee violence and persecution. World Relief and other faith-based resettlement agencies receive grants from the State Department to do the difficult work of compassion that few Americans can do.

And conservative Christian leaders have been some of the most prominent to speak out against Trump’s recent executive order on travel. Dreher writes, “Nothing matters more than guarding the freedom of Christian institutions to nurture future generations in the faith . . . other objectives have to take a back seat.” But what if “other objectives” are protecting and defending members of marginalized groups who can’t speak for themselves?

I’m genuinely perplexed by Beaty’s faulting me for not speaking out in favor of mediating institutions that Christians are involved in. One of the main points of the book is to encourage the building and strengthening of these mediating institutions. And see, this is precisely why the chapter on politics stresses religious liberty. Those grants that World Vision receives from the State Department are at risk because World Vision, owing to its theological commitments, will not hire gays in same-sex marriages. [NOTE: I misread her citing “World Relief” as “World Vision”. Those are two different organizations. I apologize for the error, but the general point I’m making here stands all the same. — RD] In fact, World Vision itself was the cause of a 2007 Bush administration memo that allows religious groups receiving federal grant money to discriminate for religious reasons in its hiring. The Obama administration left that policy in place, and was strongly criticized from the left for it. If Katelyn Beaty wants to protect the ability of World Vision to do its vital work outside the political realm, then she should prioritize defending religious liberty inside the political realm. As I write in The Benedict Option:

As important as religious liberty is, though, Christians cannot forget that religious liberty is not an end in itself but a means to the end of living as Christians in full. Religious liberty is an important component in permitting us to get on with the real work of the church and with the Benedict Option. If protecting religious liberty requires us to compromise the moral beliefs that define us as Christians, then any victories we achieve will be hollow. The church’s mission on earth is not political success but fidelity.

Another Beaty criticism:

And this leads to the most glaring omission of the Benedict Option: its utter lack of engagement with the African American church. (Of note: Throughout the book, Dreher quotes only one person of color, an Indonesian monk living in Italy.) White traditional Christians who have lost cultural power can look back through history for models of resistance. But they also have models in their very midst: black Christians, who have lived for hundreds of years under state-sanctioned violence, who have their houses of worship vandalized, who continue to be victims of racially motivated shootings — and who attest to the enduring power of the gospel to heal divisions, forgive and live with countercultural hope.

This is not a bad point. It was a judgment call on my part. The book had to come in at 75,000 words, no more. That was the space I was given. Nearly every one of the chapters I wrote could have been a book in itself (and I hope some other Christian writers will write those books). It is almost a scandal, for example, that Work chapter is focused not so much on the Benedictine theology of labor (though that is there) as it is on helping small-o orthodox Christians think about the kinds of workplace and professional challenges they are likely to face in this post-Christian environment. But I had to make those kinds of editorial decisions. I considered whether or not to write about the black church in a Ben Op context, but could not figure out how to do it, frankly, at least not in the time I had to complete the work.

It was far more than a technical challenge. I do not believe that American Christians in general will face the kind of oppression that black Christians in the Jim Crow South suffered, at least not in the foreseeable future. As someone whose last book was a collaboration with an African-American actor about his family’s rise from slavery and segregation to achieve the American dream, I did not feel right comparing the crisis the broad church is facing in post-Christian America to the crisis that the black church faced under conditions of life and death, and extreme poverty. In working on that earlier book, I sat and listened to black people tell stories that shook me to my core. It seemed to me somewhat obscene to compare the potential for suffering that the American church in general faces going forward from this historical point to the experiences of black Americans whose churches were bombed, and who had to face state-sanctioned violence, including murder, with no hope of reprieve.

I do see lessons that the broader church can learn from the black church experience that could help us deal with great adversity, but I could not figure out a way to deal with those issues in a sensitive and nuanced way — at least not in a relatively short book that addresses a wide range of big topics — without seeming to appropriate the black experience unjustly. This speaks to my limitations as a writer, I suppose, but I believe I made the right decision — though I understand people who conclude otherwise. I do hope a black Christian writer will write a book about what Benedict Option lessons the rest of us can learn from the black church experience. Frankly, it’s not a book a white author has the moral authority to write, or at least not this white author.

OK, one more passage from Beaty’s piece:

The image Dreher uses most to talk about Christian life in our modern dark age is that of the Ark (you know, Noah’s big boat). In the Bible, in the Book of Genesis, the Ark is where the righteous survive as the whole world is destroyed in a great flood. To extend the metaphor, Christians today may very well need to build Arks, or institutions, that help them preserve the faith in a culture that easily washes it away. The difference between now and the days of Noah centers on God’s promise in the Bible: He will never let a great flood destroy all of life.

Christians living in a post-Christian nation could withdraw to their Arks, waiting for their neighbors and their cultures to be destroyed in a flood of moral chaos. But if they believe God’s promises in Scripture, then they’ll get busy building communities that throw their neighbors a line of real hope amid the coming tide.

Wait … what? This is all far more complicated than she indicates. In The Benedict Option, I make use of the term “liquid modernity,” taken from the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, to characterize the nature of the cultural and religious crisis upon the West. Here’s an explanation of what “liquid modernity” means (not from the Ben Op book, please note):

Liquid Modernity is sociologist Zygmunt Bauman’s term for the present condition of the world as contrasted with the “solid” modernity that preceded it. According to Bauman, the passage from “solid” to “liquid” modernity created a new and unprecedented setting for individual life pursuits, confronting individuals with a series of challenges never before encountered. Social forms and institutions no longer have enough time to solidify and cannot serve as frames of reference for human actions and long-term life plans, so individuals have to find other ways to organize their lives.

Bauman’s vision of the current world is one in which individuals must to splice together an unending series of short-term projects and episodes that don’t add up to the kind of sequence to which concepts like “career” and “progress” could be meaningfully applied. These fragmented lives require individuals to be flexible and adaptable — to be constantly ready and willing to change tactics at short notice, to abandon commitments and loyalties without regret and to pursue opportunities according to their current availability. Liquid times are defined by uncertainty. In liquid modernity the individual must act, plan actions and calculate the likely gains and losses of acting (or failing to act) under conditions of endemic uncertainty. The time it takes to fully consider options and make fully formed decisions has fragmented.

This is the nature of our time and place. How are we Christians going to keep our heads  above water, and ride out this catastrophic flood? I present the Benedictine monasteries of the early medieval period as cultural arks that carried Christianity and elements of the Greco-Roman tradition across the dark and stormy sea between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and Charlemagne (Thomas Cahill tells a similar story about monks, though from a Celtic Christian perspective, in How The Irish Saved Civilization).

above water, and ride out this catastrophic flood? I present the Benedictine monasteries of the early medieval period as cultural arks that carried Christianity and elements of the Greco-Roman tradition across the dark and stormy sea between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and Charlemagne (Thomas Cahill tells a similar story about monks, though from a Celtic Christian perspective, in How The Irish Saved Civilization).

I can only make sense of Beaty’s comments by assuming that she completely missed the metaphors of the Flood and the Ark, despite the fact that I laid them out as metaphors in language so plain that you’d have to really work to miss the point. I am in no way saying that the world faces a literal deluge, and it’s bizarre that she read The Benedict Option in this way. And it’s an inaccurate and uncharitable reading to posit the book as encouraging conservative Christians to sit on the Lido decks of their Ben Op arks watching indifferently as their neighbors drown. Here’s a passage from the book in which a monk of Norcia explains the role hospitality plays in Benedictine life:

Brother Francis Davoren, forty-four, the monastery’s brewmaster, used to be the refectorian, the monk charged with overseeing the dining room. He approached that task with sacramental imagination.

“Saint Benedict says that Christ is present in the brothers, and Christ is present in our guests. Every day I would think, ‘Christ is coming. I’m going to make this as pleasant for them as I can, because it showed them that we cared,’” he said. “That’s a good outreach to people: to respect them, to recognize their dignity, to show them that you can see Christ in them and want to bring them into your life.”

That chapter then talks about how the Rule sets limits on hospitality, though:

Saint Benedict commands his monks to be open to the outside world — to a point. Hospitality must be dispensed according to prudence, so that visitors are not allowed to do things that disrupt the monastery’s way of life. For example, at table, silence is kept by visitors and monks alike. As Brother Augustine put it, “If we let visitors upset the rhythm of our life too much, then we can’t really welcome anyone.” The monastery receives visitors constantly who have all kinds of problems and are seeking advice, help, or just someone to listen to them, and it’s important that the monks maintain the order needed to allow them to offer this kind of hospitality.

And:

Rather than erring on the side of caution, though, Father Benedict [Nivakoff, a priest-monk in Norcia] believes Christians should be as open to the world as they can be without compromise. “I think too many Christians have decided that the world is bad and should be avoided as much as possible. Well, it’s hard to convert people if that’s your stance,” he said. “It’s a lot easier to help people to see their own goodness and then bring them in than to point out how bad they are and bring them in.”

The Benedict Option makes clear that our churches and Christian institutions are going to have to be arks not only for ourselves, but for refugees floating adrift in liquid modernity — men, women, and children who need rescue, shelter, sustenance, and community. As the book says:

This is not just about our own survival. If we are going to be for the world as Christ meant for us to be, we are going to have to spend more time away from the world, in deep prayer and substantial spiritual training—just as Jesus retreated to the desert to pray before ministering to the people. We cannot give the world what we do not have. If Israel had been assimilated by the world of the ancient Near East, it would have ceased being a light to the world. So it is with the church.

That’s what The Benedict Option actually says. How a reader gets from all this the idea that I’ve written a book for the frozen chosen to read to prepare for cruising into the Apocalypse is a mystery. Is this book so much of a threat to settled ways of American Christian thinking and living that its arguments have to be strawmanned to be dismissed?

By way of contrast, here’s a favorable review in the Weekly Standard by Andrew T. Walker, a conservative Evangelical who appears to have read a different book. Excerpt:

Dreher’s proposals have been criticized as an intellectually astute form of cultural retreat. But a careful reading puts this notion to rest. Dreher’s manifesto is suffused with a forward-looking engagement with the world. Serving and preserving Western culture may, at times, require the church to stand against it, and even subvert it. “There is a hidden blessing in this crisis,” he writes, “if we will open our eyes to it. Just as God used chastisement in the Old Testament to call His people back to Himself, so He may be delivering a like judgment onto a church and a people grown cold from selfishness, hedonism, and materialism.”

American Christianity may worry over its declining cultural influence, but Dreher sees the potential for joy in the mourning of a lost cultural hegemony. In exile, finding one’s identity means stripping off the fancy gloss and strengthening one’s resolve.

For the sake of full disclosure, Andrew is a friend, and has become one over the past couple of years as I’ve been talking about the Benedict Option project. He and Denny Burk have given me invaluable guidance in helping me to understand Evangelicalism and potential Evangelical objections to the Ben Op. They have guided my thinking, whether they knew what they were doing or not. I’m indebted to Andrew for this kind review, but more importantly, I’m indebted to him and to Denny for their friendship and counsel more than I can say.

Can Government Heal A Broken Society?

David Brooks takes stock of how radically Donald Trump has changed the Republican Party. He’s reviewing Trump’s speech to Congress. Excerpt:

The first thing we learned was that Trumpism is an utter repudiation of modern conservatism. For the last 40 years, the Republican Party has been a coalition of three tendencies. On Tuesday, Trump rejected or ignored all of them.

There used to be Republican foreign policy hawks, people who believed that it was in America’s interest to serve as a global policeman, actively preserving a democratic world order. Trump explicitly repudiated this worldview, drawing instead a sharp distinction between what’s good for America and what’s good for the rest of the world.

There used to be social conservatives, who believed that the moral fabric of the country had been weakened by secularism and the breakdown of the family. On Tuesday, Trump acted as if this group didn’t exist. He didn’t mention a single social issue — abortion, religious liberty, marriage, anything. [Emphasis mine — RD]

Finally, there used to be fiscal hawks who worried about the national debt. Trump demolished these people, too, vowing a long list of spending programs and preservation of entitlement programs.

The Republicans who applauded Trump on Tuesday were applauding their own repudiation. They did it because partisanship is stronger than philosophy, but also because Reagan conservatism no longer applies to current reality.

That last clause is especially important. Trump became the GOP nominee, and took over the Republican Party in a revolution from below because the GOP leadership had little more to offer than the same old Reaganism it has been reheating for 25 years. Do you realize that there are as many years between the time Reagan left office and Trump was sworn in as there was between Eisenhower’s inauguration’s and Reagan’s? The Republicans coasted on Reaganism for a very long time. Trump instinctively sensed that the House That Reagan Built was riddled with termites, and wouldn’t stand if it was given a shove. He was right.

George W. Bush’s calamitous war in Iraq destroyed the eagerness of Americans to serve as the world’s policeman. The fact that average Americans have fallen farther behind, and more economically insecure, while most of the economic gains of the past decades have accrued to the top of the economic pyramid has disillusioned many about the virtues of Reagan free-market ideology (which, note well, was absorbed into the Democratic Party by Bill Clinton, as Thatcherite economic neoliberalism was absorbed into the Labour Party by Tony Blair). As for social conservatism, that’s complicated, but I think it’s mostly a matter of most people not believing in it anymore, except in a nominal sense, and of people prioritizing other concerns. It’s hard to stay focused on marriage and abortion when you’re 50 years old and facing the loss of your job — and, given your age, possibly the permanent loss of employment. It’s hard to care about religious liberty when you don’t go to church, or do go, but see church as mostly a place to get a pep talk to lift you up for the week to come.

So, Reaganism is dead, but is Trumpism a coherent replacement? Brooks points out that Trump grasped that in this time of enormous flux, people want a strong government to give them some shelter from the forces disrupting the stability of their lives. Yet, says Brooks, some of Trump’s own policy proposals would introduce more instability into the lives of his voters. (And, he might have added, the Trump proposal for a massive increase in defense spending appears to contradict his stated view that America ought to draw down its military presence globally.)

The answer to the insufficiency and contradictions of Trumpism cannot be an I-told-you-so reversion to Reaganism. So what should government try to do? Brooks:

Human development research offers a different formula: All of life is a series of daring adventures from a secure base. If government can create a framework in which people grow up amid healthy families, nurturing schools, thick communities and a secure safety net, then they will have the resources and audacity to thrive in a free global economy and a diversifying skills economy.

I can buy that, but I wonder how government can create that framework. Observe that he’s not saying “if government can create healthy families,” etc. I may be parsing this too closely, but I don’t think Brooks believes that government can create these things directly — and in that, he’s right — but what government can do is to create an environment in which civil society can generate these things. For example, if the public schools are bad, or at least not what we want and need them to be, then there are some policies that could address that. But government cannot fix the broken family systems that form children who are dramatically less capable of learning, or even behaving in a disciplined way. It is not only wrong to expect public school teachers and staff to raise our kids, but it is also an impossible ask.

That’s just one example. Here’s another: there’s not a lot government can do to keep online pornography out of the hands of America’s kids. There are lots of conservative Christian parents who go to church on Sunday, send their kids to Christian school, and who silently thank God that their kids are not having to deal with the moral chaos in public schools. And yet, these same parents hand their little kids smartphones (somebody in Dallas told me that you’re starting to see seven year olds with their first iPhones) through which hardcore porn and all the other sewage on the Internet can stream uninterrupted. And we have the nerve to think that we’re better off than the world? We need to repent and get our own houses in order. How can we be light unto the world, and help heal the brokenness and suffering of modern society, when we participate so uncritically in the habits that cause its brokenness and suffering? We cannot give what we do not have.

The sickness in civil society is one of the things The Benedict Option is meant to address. The argument goes something like this:

We all live in “liquid modernity,” an unprecedented time of massive flux and instability in the lives of individuals, families, and communities;

The churches can and should be an ark of stability offering rescue, shelter, and solidarity to all people lost at sea in liquid modernity;

The church can best do that not by trying to do that directly, but by having that emerge as the by-product of its much more vigorous embrace of Christianity’s teachings and traditional practices, and a more intentional embrace of community within the church;

The church cannot serve the world as she is supposed to without relearning and recommitting herself to her own Story, which has been lost in liquid modernity; this is a story that runs strongly counter to the narrative of expressive individualism and moral autonomy at the heart of liquid modernity’s story;

Doing what needs to be done requires some substantial degree of withdrawal from participation in modern life — ceasing to “shore up the imperium,” in MacIntyre’s phrase — so that we can strengthen ourselves spiritually to bear authentic witness to the post-Christian world; continuing to think and live as if these were normal times is only going to hasten our already-significant decline;

The relative loss of Christian power and influence at the national level, and the likelihood that we will be increasingly marginalized in the public square in years and decades to come, means that we should redouble efforts to engage and transform our local communities — which is a form of practical politics. To this end, I quote Yuval Levin, from his important 2016 book The Fractured Republic , a passage in which he addresses social and religious conservatives:

The center has not held in American life, so we must instead find our centers for ourselves as communities of like-minded citizens, and then build out the American ethic from there. . . . Those seeking to reach Americans with an unfamiliar moral message must find them where they are, and increasingly, that means traditionalists must make their case not by planting themselves at the center of society, as large institutions, but by dispersing themselves to the peripheries as small outposts. In this sense, focusing on your own near-at-hand community does not involve a withdrawal from contemporary America, but an increased attentiveness to it.

One thing that strikes me about many of the early reactions to the book is how hard it is for people today to think of public engagement outside of the realm of electoral politics. This gets things backward. In classical thought, a disordered and weak polity is the result of disorder and weakness within the hearts and minds of the people within it. Government is vital to social stability and to midwifing broad practices and structures within a society, but it is not a church. Only the church is the church. As Tocqueville understood, the health of a democracy depends on the health of its churches. Yes, Christians must still vote and stay engaged to some degree with conventional politics, but at the core, the rebuilding of an unwell society starts at the local level, in our own churches. In The Benedict Option, I quote Vaclav Havel (an unbeliever, by the way) giving advice to those dissidents in his own country who could not and would not shore up the communist imperium:

“A better system will not automatically ensure a better life,” Havel goes on. “In fact the opposite is true: only by creating a better life can a better system be developed.”

The restoration will be long, a project of many decades, perhaps even centuries. If the church is to play a role in it, the church must know who she is — and who she is not. The old Religious Right is dead; there is no “Moral Majority” by social conservative standards. It’s a different world. I talked this week to a Christian interviewer who said that a number of his church friends believe that with Trump’s election, the danger to the church has passed, and everything is back on track. If you believe that, you are dangerously deluding yourself. The fault for this is not on Trump; it’s on you.

‘Crisis? What Crisis?’ Said His Church

A reader sent me an e-mail on Wednesday night, saying he wanted to tell me about his efforts to convince the leadership of his Evangelical church to approve a congregational study of The Benedict Option when it comes out on March 14. I publish his e-mail below with his permission. I have only very slightly edited it to remove the name of the church:

I explained that I long thought that [name of church] did an outstanding job of teaching kids Scripture and a Christian worldview from Nursery through Senior High through a variety of classes, small groups, and preaching. But the campaign of 2016 revealed that a lot of late teens and 20s aged young people sought out influences and ideas that are corrosive and possibly even inimical to a true Biblical worldview.

We went through some of the gay marriage stuff, the Jen Hatmakers of the world, and so on. And I talked about how, even at our own church, the experience of worship was becoming atomized – plenty of people just “take what they need and leave the rest behind”. We don’t pray any common prayers, recite any creeds, or participate in truly unified things (other than singing and listening to preaching) besides once-per-month Communion. And I recommended The BenOp book study as a way of reconnecting people to our ancient faith and the modern world and thinking about how the Church moves forward in this culture.

To make a long story short, they simply didn’t buy it. They waved away a lot of the articles and ideas of scholars, writers and philosophers – “we already do those things”. They dismissed the “likes” and “shares” and affirmations of untrained and destructive Christian bloggers and speakers as just “young people finding their way”, and “making the mistakes youth make”. Despite all of the research and observations to the contrary, they just don’t think its anything to worry about.

I tried to patiently explain that although many people hold the right beliefs (orthodoxy), absent any pressure to hold on to them, they will eventually succumb to the cultural pressures to abandon many of those beliefs, especially surrounding sex and the family. We’re seeing that happen. And perhaps the answer is to consider more orthopraxy to strengthen the orthodoxy. Perhaps some common prayers, hymns that everyone knows, Communion more often, celebrating some of the ancient Christian practices like Ash Wednesday and so on. No, no, and no. And they have no interest in a class featuring a book written with such an Orthodox and Catholic focus. I suggested they listen to what Al Mohler has to say in his podcast, but I don’t expect that to go anywhere.

[This church] believes in and encourages people to fast and pray. So why do we not “do” Ash Wednesday? It’s simply because they look at anything even remotely “traditional” as the dead hand of the past and nothing more. There is a refusal to even consider that what sustained the church for thousands of years, practices that great men and women of the faith recommended, are still useful. They won’t even look.

And for all of the instruction to kids and youth and adults, the same pattern will happen: as soon as they achieve some measure of independence, they’ll drift to a church or ideas that allow them to live in peace with the culture, not their faith — the latter will be jetsam.

I hold out hope that my church’s leaders may be right, but I don’t believe that they are. All the Scripture knowledge in the world is not going to do any good unless people know how it fits together and they are truly “prepared to give an answer for the hope they have.” Not in an apologetics sense, but in a Grand Narrative sense.

This morning my wife and I attended a small Ash Wednesday service at an Anglican church and it was lovely. The priest marked me with ashes and I felt what I can only describe as the joy of the Spirit.

I brought this reader’s e-mail up with a well-connected and knowledgeable Evangelical friend, who responded:

My own experience mimics this. Offer anything beyond a middle school level argument, and 90% of people will tune you out. This isn’t an Evangelical problem, it’s an American problem. We are far more American than Christian.

He’s right about that. This isn’t an Evangelical problem. It’s an American Catholic problem too. It’s an American Orthodox problem. It’s an American problem, period. If the American churches are doing everything right, how do we explain sociologist Christian Smith’s shocking findings? How, for example, do we account for the fact that, according to Smith’s research, 60 percent of American Christians aged 18 to 23 say they have no problem whatsoever with materialism and consumerism, and 31 percent say that they have some qualms about these things, but they can’t do anything about it, so … whatever? How do we explain the fact that religion is collapsing among younger Americans — especially young men — at a rate never before recorded? How do we account for research indicating that the percentage of Americans who don’t pray or believe in God has “reached an all-time low”?

These things aren’t just happening. They’re happening for a series of reasons. The churches who continue to behave as if these are normal times are going to die. Look at Europe. We used to think we were immune to that in the United States. We can no longer say that.

The Benedict Option is for Christians to whom it is more important to be a faithful and obedient follower of Jesus Christ than it is to be a good 21st-century American. There doesn’t necessarily have to be a conflict, but when there is, we have not only to know which one to choose, but also to have the strength of heart to choose it.

I would only offer to the leaders of this reader’s church — and maybe your church too — these lines from The Benedict Option:

How do we take Benedictine wisdom out of the monastery and apply it to the challenges of worldly life in the twenty-first century? It is to this question that we now turn. The way of Saint Benedict is not an escape from the real world but a way to see that world and dwell in it as it truly is. Benedictine spirituality teaches us to bear with the world in love and to transform it as the Holy Spirit transforms us. The Benedict Option draws on the virtues in the Rule to change the way Christians approach politics, church, family, community, education, our jobs, sexuality, and technology.

And it does so with urgency. When I first told Father Cassian about the Benedict Option, he mulled my words and replied gravely, “Those who don’t do some form of what you’re talking about, they’re not going to make it through what’s coming.”

Readers, I’m going to be away from the keys for much of today. I have scheduled a few posts to automatically publish throughout the day. You’ll have fresh reading, but approving comments is going to be slow. Thanks for your patience.

March 2, 2017

Papally Blessing The Love Shack

The welcoming of those young people who prefer to live together without getting married… https://t.co/fa7xr0TXZ4 pic.twitter.com/zYrsrfhvcl

— Antonio Spadaro (@antoniospadaro) February 26, 2017

In case you don’t know, Antonio Spadaro, SJ, is a close advisor to Pope Francis, and editor of the Jesuit-run journal La Civiltà Cattolica.

European Elites May Martyr Marine Le Pen

European Union lawmakers lifted the EU parliamentary immunity of French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen on Thursday for tweeting pictures of Islamic State violence.

Le Pen, who leads her National Front party in the European legislature, is under investigation in France for posting three graphic images of Islamic State executions on Twitter in December 2015, including the beheading of American journalist James Foley.

Le Pen’s immunity shielded her from prosecution. By lifting it, after a request from the French judiciary, the parliament is allowing any eventual legal action against her.

The move grants the prosecutor looking into the affair power to bring Le Pen in for police questioning.

In the next steps, the prosecutor could drop the case, appoint an investigating magistrate to delve further into it, or send it straight to trial. A trial date ahead of the election in April and May would require the French legal process to go much faster than it normally does.

The law under which Le Pen could be charged forbids “publishing violent images”. Presumably if Le Pen had tweeted out clips from “Pulp Fiction,” she could also have been brought up on charges. Right?

But let’s be serious: Le Pen is being threatened with prosecution because she tweeted out actual images of actual murders carried out by Islamic militants. These images are ones that European elites would prefer not to see, and would prefer that their peoples not see, because they raise uncomfortable questions about Islamic radicalization and terrorism in Europe itself. Those questions raise more questions about what European governing elites are doing — or rather, not doing — to deal effectively with the threat inside Europe.

Therefore, Marine Le Pen must be silenced and punished for telling truths that are inconvenient to the European elites.

If I were her, I would say, “Bring it on!” If the ruling class is going to persecute Le Pen for tweeting images of actual events, they’re going to dig their own political graves. If they believe that Le Pen is using those images in an inflammatory or misleading way, then make that argument. But trying to throw her into the dock for tweets that are not false or defamatory is madness. They are going to make a free-speech martyr out of her — and hand her the French presidency.

UPDATE: James C. comments:

And why did she tweet those images? Because a French journalist equated her party to the Islamic State! In response to that outrageous provocation, she addressed him and posted images with the caption, “Daesh c’est ÇA!” (Daesh is THIS!).

These ‘mainstream’ globalist eurocrats and their media allies will stop at nothing.

And Noah172 says:

You write that Le Pen might be “martyred” figuratively, but Wilders in the Netherlands might get martyred literally: he recently had to cancel all public appearances because police uncovered collusion of a Muslim Dutch policeman assigned to Wilders’ security with Muslim criminals.

Noah is right. Here’s the shocking story:

With less than 2 weeks until Dutch election, the government has assigned special forces of the Dutch military to protect the frontrunner Geert Wilders, European newspapers report.

Europe’s most prominent critic of Islam and leader of the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV), Wilder had suspended his public campaign last week after a police officer serving in his security detail was arrested for leaking details about his movements to Moroccan-Muslim criminal organisation.

With promises of ‘de-Islamising’ the Netherlands and taking the country out of the European Union, Wilders has been leading the polls ahead of the March 15 election. The result of the election in the Netherlands is bound to set the tone for the two major elections coming up in Europe later this year: the France presidential election in April-May and the German parliamentary election in September.

Dutch Government’s move, to transfer Wilders’ security over to the country’s military, points to the lack of faith in country’s law enforcement to protect the life of PVV leader who has been on the crosshairs of international Jihadi groups for more than a decade.

More on the story, in The Guardian, from late February:

Dutch media reported this week that a member of the far-right politician’s police security team had been arrested on suspicion of leaking details of his whereabouts to a Dutch-Moroccan criminal gang.

The Algemeen Dagblad newspaper reported on Thursday that the officer and his brother, both previously members of the Utrecht police force, had also been investigated in the past in connection with suspected leaks of confidential information.

The DBB security service, responsible for the safety of the royal family, diplomats and high-profile politicians, said the officer, of Moroccan origin, was not one of Wilders’ bodyguards but screened locations for his public appearances.

You may remember that in 2002, Pim Fortuyn, who was the leading candidate for Dutch prime minister, was shot dead shortly before the election. His killer was a young environmental extremist who said he acted to protect Muslims, whom Fortuyn criticized for their radicalism. This is not a joke in the Netherlands.

Resisting The Dictatorship Of Relativism

Thinking further about Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig’s criticism of the Benedict Option for being insufficiently dedicated to participation in the liberal democratic project, I struggled to understand her point, given that in The Benedict Option book, I talk about how Ben Op Christians have to stay engaged in normal politics to some degree. In the book, I lay out an alternative form of political engagement, one that I believe small-o orthodox Christians should take up in compensation for what will become our increasingly marginalized role in the public square. She didn’t address that in her review, no doubt because she believes that there is still a meaningful place at the table for orthodox Christian believers. I think she’s wrong about that, obviously, but I still couldn’t shake the feeling that Ben Op political critics don’t quite grasp what I’m trying to say.

Then it hit me. An explanation so clear that it deeply chagrins me that I didn’t think of it when I was writing the book. From the homily Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger gave at the outset of the 2005 conclave from which he emerged as Benedict XVI:

How many winds of doctrine have we known in recent decades, how many ideological currents, how many ways of thinking. The small boat of the thought of many Christians has often been tossed about by these waves – flung from one extreme to another: from Marxism to liberalism, even to libertinism; from collectivism to radical individualism; from atheism to a vague religious mysticism; from agnosticism to syncretism and so forth. Every day new sects spring up, and what St Paul says about human deception and the trickery that strives to entice people into error (cf. Eph 4: 14) comes true.

Today, having a clear faith based on the Creed of the Church is often labeled as fundamentalism. Whereas relativism, that is, letting oneself be “tossed here and there, carried about by every wind of doctrine”, seems the only attitude that can cope with modern times. We are building a dictatorship of relativism that does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one’s own ego and desires.

We, however, have a different goal: the Son of God, the true man. He is the measure of true humanism. An “adult” faith is not a faith that follows the trends of fashion and the latest novelty; a mature adult faith is deeply rooted in friendship with Christ. It is this friendship that opens us up to all that is good and gives us a criterion by which to distinguish the true from the false, and deceipt from truth.

We must develop this adult faith; we must guide the flock of Christ to this faith. And it is this faith – only faith – that creates unity and is fulfilled in love.

On this theme, St Paul offers us as a fundamental formula for Christian existence some beautiful words, in contrast to the continual vicissitudes of those who, like children, are tossed about by the waves: make truth in love. Truth and love coincide in Christ. To the extent that we draw close to Christ, in our own lives too, truth and love are blended. Love without truth would be blind; truth without love would be like “a clanging cymbal” (I Cor 13: 1).

The dictatorship of relativism is a far greater threat to the future of the Christian faith in the West than the Democratic Party or any Washington politician. Benedict Option Christians realize that:

a) politics is not limited to elections and statecraft, but encompasses the way we live our lives together in public; and

b) the primary political responsibility of Benedict Option Christians is to resist in love the dictatorship of relativism.

We must all be dissidents from the dictatorship of relativism. From The Benedict Option:

In thinking about politics in this vein, American Christians have much to learn from the experience of Czech dissidents under Communism. The essays that Czech playwright and political prisoner Václav Havel and his circle produced under oppression and persecution far surpassing any that American Christians are likely to experience in the near future offer a powerful vision for authentic Christian politics in a world in which we are a powerless, despised minority.

Havel, who died in 2011, preached what he called “antipolitical politics,” the essence of which he described as “living in truth.” His most famous and thorough statement of this was a long 1978 essay titled “The Power of the Powerless,” which electrified the Eastern European resistance movements when it first appeared.4 It is a remarkable document, one that bears careful study and reflection by orthodox Christians in the West today.

Consider, says Havel, the greengrocer living under Communism, who puts a sign in his shop window saying, “Workers of the World, Unite!” He does it not because he believes it, necessarily. He simply doesn’t want trouble. And if he doesn’t really believe it, he hides the humiliation of his coercion by telling himself, “What’s wrong with the workers of the world uniting?” Fear allows the official ideology to retain power—and eventually changes the greengrocer’s beliefs. Those who “live within a lie,” says Havel, collaborate with the system and compromise their full humanity.

Every act that contradicts the official ideology is a denial of the system. What if the greengrocer stops putting the sign up in his window? What if he refuses to go along to get along? “His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth”— and it’s going to cost him plenty.

He will lose his job and his position in society. His kids may not be allowed to go to the college they want to, or to any college at all. People will bully him or ostracize him. But by bearing witness to the truth, he has accomplished something potentially powerful: He has said that the emperor is naked. And because the emperor is in fact naked, something extremely dangerous has happened: by his action, the greengrocer has addressed the world. He has enabled everyone to peer behind the curtain. He has shown everyone that it is possible to live within the truth.

Because they are public, the greengrocer’s deeds are inescapably political. He bears witness to the truth of his convictions by being willing to suffer for them. He becomes a threat to the system—but he has preserved his humanity. And that, says Havel, is a far more important accomplishment than whether this party or that politician holds power (a fact that became painfully clear during the debasing 2016 U.S. presidential campaign).

“A better system will not automatically ensure a better life,” Havel goes on. “In fact the opposite is true: only by creating a better life can a better system be developed” (emphasis mine).

The answer, then, is to create and support “parallel structures” in which the truth can be lived in community. Isn’t this a form of escapism, a retreat into a ghetto? Not at all, says Havel; a countercultural community that abdicated its responsibility to reach out to help others would end up being a “more sophisticated version of ‘living within a lie.’”

There you have it. At its most fundamental, the politics of the Benedict Option amounts to becoming dissidents — guided by truth in love — resisting the dictatorship of relativism.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers