Rod Dreher's Blog, page 237

June 5, 2019

Law Of Merited Impossibility, California-Style

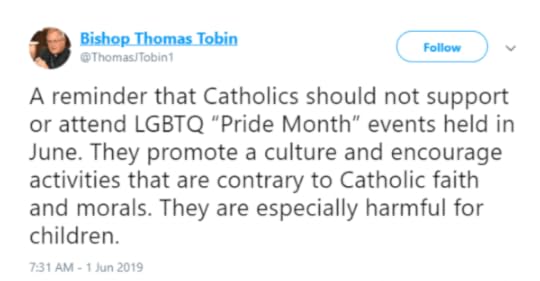

Michael Brendan Dougherty says this is an illustration of the Law of Merited Impossibility (“It will never happen, and when it does, you bigots will deserve it”), in three tweets:

Advertisement

Catholics And Evangelicals Apart

Michael Brendan Dougherty — a traditionalist Catholic — offers an intriguing insight onto the Sohrab Ahmari/David French dust-up. He wonders if the fact that Ahmari is Catholic and French is Evangelical has something to do with the Ahmari’s political pessimism and French’s political optimism. Evangelicals, says MBD, have grown greatly, and become more morally conservative since mid-century. But:

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church’s growth as it touches the United States is only by movement, into and around. Some dioceses are growing, particularly in the American South, due to internal migration. And then there is immigration into the country. But since the Second Vatican Council, the trend is toward a massive fall off in practice. There is the massive, humiliating, sex-abuse crisis, implicating every level of the hierarchy. It has experienced the dissolution of the ethnic communities that sustained the archipelago of parochial schools, which are closing faster than they are opening. Many major dioceses are set to close and combine parishes: Boston, New York, Chicago. On the political front, the Catholic Church’s massive network of institutions — its hospitals, colleges, charities, and adoption agencies — have a public-facing mission that makes them the recipients of state and federal dollars. They are operating in industries that hardly exist apart from state funding and heavy regulation, which makes them vulnerable. Barack Obama, a president whose political career began within the Catholic Church’s social movements, turned around and had his Secretary of Health and Human Services specifically put the Church’s unpopular doctrine against the use and provision of artificial birth control into a major public controversy. Catholic adoption agencies are still being closed due to the application of non-discrimination principles. The ACLU has started testing legal tactics against Catholic health-care facilities and their prohibition on abortion.

Theologically, Catholic conservatives and traditionalists are more cohesive than they were before, say, 2007. But clearly they are on the wrong side of the current papacy. The pope defeated them handily in a controversy over divorce and the sacraments. Catholics also expect that the leaders of their prized institutions are often not-so-secretly on the other side. See how the president of Notre Dame — a priest — could not even take his own institution’s side in the birth-control debate. And more recently rejected calls from students to ban access to pornography on campus Wi-Fi.

To be clear, MBD doesn’t make an extended case. He offers it as just a passing insight. But I sense that there’s something substantive here. What we are seeing now is in part the result of the absence of Richard John Neuhaus from the scene, and the failure of the Neuhaus-Weigel-Novak project to reconcile orthodox Catholicism with liberal democracy and capitalism.

You can blame them for betting so heavily on the Iraq War and the Republican Party, and you would have some grounds for it. But my sense is that the greater fault lies with the fact that they bet even more heavily — and understandably! — on institutional Catholicism. They had no idea that the deeds of the Catholic bishops and the abusive priests for whom they covered up would destroy the moral authority of the Church.

But even if the abuse crisis had never happened, I strongly doubt that the Catholic Church would be in much different circumstances today. Boston broke the scandal wide open in 2002, but the decline lines were well established in US Catholicism, since the 1960s and the Council. When John Paul II was pope, it was possible to convince oneself that the Church was repairing itself after the disastrous 1970s, and that maybe even Father Neuhaus was right that America was headed towards a “Catholic moment.”

It was certainly true that the intellectual confidence of Catholics in the 1980s and 1990s was intoxicating. I was mesmerized by it, and converted. It surprised me to discover that the difference between on one side, the Catholic Church of John Paul II and the Church I was reading about in the pages of First Things magazine, and on the other side the actual real-life American parishes, was jarring. Still, a number of us took it for granted that things were going to get better and better once the John Paul II bishops cleaned things up.

There was also among some of us right-of-center Catholic egghead types a barely concealed condescension towards Evangelicalism. One admired their zeal, certainly, but bless their hearts, they just don’t have the intellectual deep bench that we do. I really did think like that, and I wasn’t the only one.

I have heard it said that some Arab Muslim students who come to the US struggle to reconcile the lush greenness of the lands of the infidels with the fact that Americans do not hold the true faith. Why does Allah bless the unbelievers, but compel His faithful to live in the deserts? This may not be true, but I can see that kind of logic possibly at work among American Catholics, versus Evangelicals. I was never an Evangelical, and did not take Christianity seriously at all until I converted to Catholicism as an adult in my mid-twenties. But I remember thinking at the time that Evangelicalism was doomed, ultimately, to fall prey to the forces of dissolution in American culture, because it lacked a Magisterium (the teaching authority of the Catholic Church), which was a solid rock. A few years into practicing Catholicism, I found myself struggling to reconcile that triumphalist belief with the fact that on certain matters of basic Christian morality, Evangelicals did a much better job of holding to Christian orthodoxy than we Catholics did.

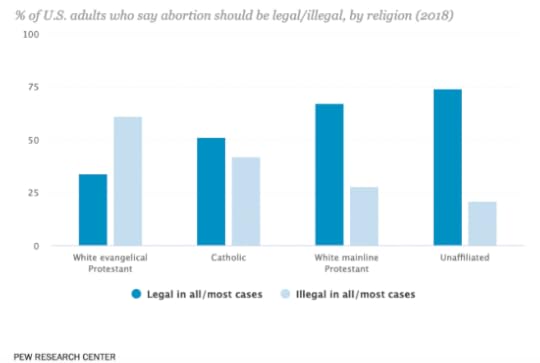

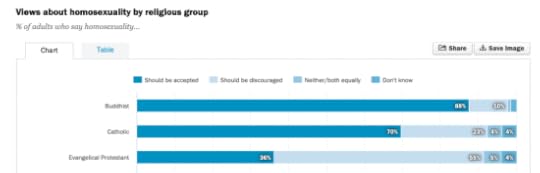

In fact, today, white US Evangelicals hold more faithfully to magisterial Catholic teaching about abortion and homosexuality than US Catholics do:

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. That’s not how the script read. But that’s what happened. And, as MBD observes, the ascent of Pope Francis has been a series of gut punches for orthodox Catholics — trads and ordinary theological conservatives both — who had grown comfortable under JP2 and Benedict XVI. This wasn’t in the script either. But it has happened.

I think it’s hard for Evangelicals to appreciate how strange it is for conservative Catholics, who, unless they go to a Latin mass parish, are almost always going to be the minority in their parishes. The common Evangelical experience of knowing that just about everybody else with you in your congregation shares the same belief is alien to most Catholics. This gives individual Evangelical congregations more coherence, and, I think, confidence.

On the other hand, I wonder if there’s a grass-is-always-greener factor at work here. A decade ago, Michael Spencer, who has since died, published a widely commented-on essay called “The Coming Evangelical Collapse,” in which he predicted that within ten years, most Evangelical churches and institutions will have fallen apart.

Well, he pretty clearly got the timing wrong. But parts of his essay still seem relevant today. Such as this excerpt from Spencer’s analysis of what’s driving the collapse:

2) Evangelicals have failed to pass on to our young people the evangelical Christian faith in an orthodox form that can take root and survive the secular onslaught. In what must be the most ironic of all possible factors, an evangelical culture that has spent billions of youth ministers, Christian music, Christian publishing and Christian media has produced an entire burgeoning culture of young Christians who know next to nothing about their own faith except how they feel about it. Our young people have deep beliefs about the culture war, but do not know why they should obey scripture, the essentials of theology or the experience of spiritual discipline and community. Coming generations of Christians are going to be monumentally ignorant and unprepared for culture-wide pressures that they will endure.

Do not be deceived by conferences or movements that are theological in nature. These are a tiny minority of evangelicalism. A strong core of evangelical beliefs is not present in most of our young people, and will be less present in the future. This loss of “the core” has been at work for some time, and the fruit of this vacancy is about to become obvious.

3) Evangelical churches have now passed into a three part chapter: 1) mega-churches that are consumer driven, 2) churches that are dying and 3) new churches that whose future is dependent on a large number of factors. I believe most of these new churches will fail, and the ones that do survive will not be able to continue evangelicalism at anything resembling its current influence. Denominations will shrink, even vanish, while fewer and fewer evangelical churches will survive and thrive.

Our numbers, our churches and our influence are going to dramatically decrease in the next 10-15 years. And they will be replaced by an evangelical landscape that will be chaotic and largely irrelevant.

4) Despite some very successful developments in the last 25 years, Christian education has not produced a product that can hold the line in the rising tide of secularism. The ingrown, self-evaluated ghetto of evangelicalism has used its educational system primarily to staff its own needs and talk to itself. I believe Christian schools always have a mission in our culture, but I am skeptical that they can produce any sort of effect that will make any difference. Millions of Christian school graduates are going to walk away from the faith and the church.

There are many outstanding schools and outstanding graduates, but as I have said before, these are going to be the exceptions that won’t alter the coming reality. Christian schools are going to suffer greatly in this collapse.

I would like for readers who are Evangelical, and active within Evangelicalism, to tell me why Spencer’s prophecy of doom has not come to pass. Is it still valid, and he simply got the dates wrong? Because I’ll tell you, everything he says here is confirmed for me anecdotally by Evangelicals I meet in my travels, and with whom I’m in touch weekly. And the sociologist of religious Christian Smith found that emerging adult Evangelicals are very much on the same path of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism as their Catholic counterparts, who are farther gone. One noted Evangelical leader I met in my travels a couple of years ago that he used to think Evangelicalism was going to hold to Biblical orthodoxy on LGBT matters, but now has given up that expectation. Just the other day, an Evangelical academic friend said to me:

American Christians, with a tiny handful of exceptions, have no means of self-defense, nothing, nil, nada. They are completely at the mercy of the culture, and completely in denial about it.

To sum up: maybe what looks to demoralized Catholics like justified Evangelical self-confidence is more of a false front than even many Evangelicals know.

I don’t know, gang. What do you think?

Here’s part of it too, I’m guessing (notice that I’m using these hedge words; a lot of this is just speculation). French tweeted recently:

It seems to me that many of the Christian opponents of classical liberalism not only believe the following words to be false but to be actually destructive, over time, to public virtue and religious orthodoxy: pic.twitter.com/vtq2lbHmpT

— David French (@DavidAFrench) June 4, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

I’ve seen over the years that Evangelicals tend to be much more bullish on the American project than Catholics. I’m not saying that Evangelicals are more patriotic than Catholics. I’m saying that Evangelicals, in general, have nurtured an esteem for the Founding that is harder to find among Catholics — who, patriotic though they may be, may have philosophical doubts. It’s significant that French quoted from the Declaration of Independence as if to call into question the good faith of Christian (Catholic) critics of classical liberalism. Don’t misread me: I don’t think he was trying to be insulting, or was insulting. I think, actually, that his is an important point! Was America founded on a half-truth, a lie, or (less harshly), a philosophical mistake?

The American political order is Protestant and Enlightenment, so it’s obvious why Evangelicals would be more at ease within it, and why Catholics would have philosophical problems with it. It was just over a century ago that the Vatican denounced the heresy of “Americanism,” which held in part that Church and State should be separate, and that the consciences of individual Catholics should have more liberty from Church teachings. Of course the Second Vatican Council revised many of these teachings; I only bring them up here to say that skepticism of classical liberalism is deep in the Catholic thought.

In my case, I share most of that skepticism, but the bone that gets stuck in my own throat is the question, “What’s a better system for us than classical liberalism?” Like most Americans (including, I would wager, American Catholics), I would not stand one second for integrating the US political order with the Catholic Church, or any church (if such a thing were possible). The problem with this is that liberalism itself behaves like a rival religion, one that doesn’t understand itself as a religion.

I have no good answer here. I’m still thinking through it. The Ahmari-French dispute, though it has had some regrettable manifestations, has been really helpful in spurring thought and conversation. Finally, everybody would benefit from reading Michael Hanby’s essay on “The Civic Project Of American Christianity” — which is about the meaning of politics for Christians in a post-Christian world. It might have been subtitled, “Father Neuhaus is dead, and I don’t feel so good myself.”

Advertisement

June 4, 2019

Courtship & Republicans

Scene from Whit Stillman’s “Metropolitan” (‘Metropolitan’ trailer screengrab)

I had a conversation recently with a high school teacher, about the question of dating, and male-female relations. She’s in her early 30s, and was talking at length about the difficulties of finding a partner to settle down with. She was really insightful.

One of the things she mentioned is observing the destructive way high school girls talk about boys. She said that they use the words “humiliation” and “assault” to describe normal social interaction. She indicated that these girls are intentionally fragilizing themselves, and whether they know it or not, making themselves unattractive to males because they turn ordinary male teenage awkwardness into a pathology.

The teacher also said — speaking of her own generation — that there is something about men of her generation that is strikingly immature. She doesn’t know why. But she also said that her generation is so self-sabotaging in that everybody wants to be happy, but nobody wants any commitments that would constrain their choices. They can’t understand that in order to get the things that will make them happy, she said, they have to surrender a significant amount of their autonomy — and that’s a thing that they will not do. She faulted herself somewhat for this.

Listening to her talk, I realized that trends that began with my generation (1980s) had hardened in subsequent generations. A lot of us were terrified of commitment, even though we wanted goods that could only come through commitment. The famous Generation X irony was a strategy to protect oneself in a social environment in which commitment was seen as making oneself vulnerable to disaster. This is what you get from a culture of divorce.

But I was like that in my teens and twenties, and my parents had not divorced, nor had most of the parents of my friends. I recall a sense of near-paralysis in the face of all the choices one could make about how to live one’s life. You could get so afraid of making the wrong choice that you passed up the opportunity to choose at all. The teacher told me that among her circles in college and right out of college, everybody was really, really anxious about making choices that would hamper their ability to rise. But rise to what, exactly? This is the number that Zygmunt Bauman’s liquid modernity does on male-female relationships.

Anyway, all that came to mind when I read this e-mail from a reader, which I post with his permission. He’s commenting on the Apocalypse GOP thread:

In my view, there’s nothing unique about the inability of the Republican Party to attract young people. Color me somewhat cynical, but the politics of the young come down to the following:

– Free stuff;

– I can do whatever the f*ck I want.

As a proud Gen. Yer, I don’t speak for everyone, certainly, but the above are the two most commonly-heard refrains with regards to how young people relate with both state and society here in the West. Because we’ve lived in such luxury compared to the rest of the world, it’s become easier (and more fashionable) to focus on the things we don’t have. It’s the difference between being given something as opposed to earning it – what’s given possesses less value than something that’s been earned.

The second point both complements and contradicts the first. Because they’re young, it’s not that they lack the mental capacity nor the life experience, but rather that they haven’t thought these things through all that well. If they did, they’d see the paradox of demanding the government giving you free stuff while insisting on your freedom to whatever you please – if you rely solely on the state to satisfy your every need and desire, then how on Earth are you able to do “whatever the f*ck you want?” Where it complements the first point is that because the young in the West haven’t had to pay much a price for a lot of what we enjoy here, they honestly believe adding a few more items to that shopping list won’t break the bank. The appreciation for what it takes to build and sustain a society simply isn’t there.

There’s one more thing – a lack of meaning in life. My best friend currently is a guy who shares nothing in common with me politically, but he trusts me enough to reveal that he feels his life ought to serve a grander, more meaningful purpose and this has an effect on how satisfied he feels. What’s interesting is that young people in general feel this way – that they want their lives to have more meaning, but they seem to think they’re the first generation to feel this way. I think every generation has sought more meaning in their lives, it’s just that older generations have discovered that meaning for themselves on an individual basis. Young people, on the other hand, want two things that aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, but aren’t always inclusive, either – meaning on their terms, while still belonging to something greater than themselves.

How does this translate into the future of the GOP? Keep in mind – Gen. Y and Z will become old one day. And my friend is wrong when he says history follows a straight line in one direction – this is impossible, because we get old and die. Not only do some ideas die with us, but some ideas change as well. The history of society and the world is one of cycles and while the GOP may be in for some choppy waters, I don’t think any of this spells our death-knell.

And if it does? I suggest we do what we always should do – take it for granted that things will work out and keep our wheels turning. What other option is there?

I don’t think we should take it for granted that things will work out. I think we should maintain hope that if we trust God and live for Him, all things will work out for the best, even if that means suffering for us. But we shouldn’t be fatalistic.

Why am I putting these two ideas together? Because my conversation with the teacher began with her saying that her generation (Millennials) has a collective sense that things ought to be shared in common, but at the same time they think and live as hyper-individualists. She can’t understand it. Seems to me like the reader who wrote has a pretty good sense of it.

Thoughts? Please do your best to restrain yourself from whataboutist griping about the GOP and Wall Street, foreign wars, and so forth. I’m going to police the thread more closely, solely to keep the discussion focused on whether or not there are connections between the socialization of generations as atomized consumers, and their much greater interest in a party and political orientation that valorizes greater personal autonomy and personal subsidies.

Advertisement

Mx. Steel, Male Penetration, & The New Normal

The Maimonides Option

Reader Yehoshua Kahan writes:

As an Orthodox Jew (an ultra-Orthodox Jew, even), I follow these intra-Christian debates with some interest. You see, my community has been for many centuries a small and embattled minority, struggling to survive in the midst of a triumphant and hostile majority. Whether in pre-Christian Rome, in Christendom, in the Islamic lands, in Enlightenment Europe and now the post-Christian West, we are and have been a minority. So I find the transition of the Christian majority to minority status interesting, and I wonder if you will learn the lessons of our history?

We fought the Romans. Not once, but twice. We bloodied them in battle, we destroyed Roman armies. And we lost our country, and our city, and our Temple. Our dead littered the land, our young were led off in chains to be torn apart in amphitheatres, or to labor in Roman mines, or to serve in Roman pleasure-houses.

We did not get our country back for a very long time.

Under the Church, we kept our heads down, we understood that we were a minority. We suffered from you–oh, how we suffered!–but we survived. We’re still here. We’re growing, and thriving.

Immediately after the Holocaust, religious Jewry was virtually dead. There were certainly not as many as a hundred thousand religious Jews in the world. Today there are probably over a million. In a hundred years there will be many millions.

We survived because we acknowledged our weakness, we bore children, and we built schools and communities where we could pass our beliefs and our values on to our children.

Do you want to survive in a post-Christian world? Learn the lessons of our history. Accept that you are no longer the rulers, have children, and labor mightily to pass on your beliefs and values to your children. Or you could follow our earlier example and “fight the Romans.” In which case, may G-d have mercy on you, and spare you the suffering which we so long endured.

In The Benedict Option, I have a passage saying that we Christians must now learn from the practices of Orthodox Jews. I planned an entire chapter on that, but I had to edit a lot out. (You should have seen the response my editor sent when I transmitted the first draft of Chapter Two at over 18,000 words, and told her that I wasn’t sure about it, because it seemed sketchy.)

Anyway, I wish some Christian writer would do an entire book on learning cultural and religious survival skills from Orthodox Jews.

Along these lines, a Jewish friend e-mails:

The “Incels and Socialism” author turned my mind toward my own religious world — the “modern” end of Modern Orthodox Judaism. I point that out because it’s not a world where everyone is married by 22 or so — but it is a world where there’s enormous pressure to be married by 24-28 (once graduate degrees are complete or in motion). And … overwhelmingly, this happens. I have single-male-30-something friends out here — and while it’s a different game in the midwest than in, say, NYC, DC, LA, Chicago, or Miami — they don’t despair in the same way. (Are there moments of frustration and sadness — yes — but, I think, in a way that seems perfectly run-of-the-mill).

So what’s different? The shadchen, I think — the matchmaker, whether we’re talking digital versions (online dating services used exclusively by the religious) or the living, breathing 21st-century update of Yente. I’ll admit — fresh from college, on course to be married by 25, I thought the idea of a matchmaker was weird. But it’s not. They’re good at what they do: set up dates that won’t end disastrously between two people with shared religious commitments. If you’ve finished college and not on the Upper West Side or in Silver Spring, MD, I’ve learned, it’s hard to find single people your age you might date. There’s no more shame, within my shul of PhDs, attorneys, and physicians, in having been set up by a shadchen than having met online.

So the matchmaker continues on — and provides an important service. If nothing else, the existence of matchmaking services helps to alleviate the sense of despair that the author of the letter you posted feels, at least among many. He’d say, I suspect, that he’s isolated: from a Jewish perspective, so is my shul. We don’t have a matchmaker among us, but members do connect with those in nearby major cities, or out of NY. It might be worth thinking about this role — as both a profession and a community service — within the context of orthodox Christian communities — both BenOp and not.

Advertisement

Apocalypse GOP

David Brooks says that the Republican Party is headed off a cliff. He points out statistics showing that Millennials and Generation Z are very, very alienated from conservatism and the GOP. Excerpt:

These days the Republican Party looks like a direct reaction against this ethos — against immigration, against diversity, against pluralism. Moreover, conservative thought seems to be getting less relevant to the America that is coming into being.

Matthew Continetti recently identified the key blocs on the new right in an essay in The Washington Free Beacon. These included the Jacksonians (pugilistic populists), the Paleos (Tucker Carlson-style economic nationalists), the Post-Liberals (people who oppose pluralism and seek a return to pre-Enlightenment orthodoxy). To most young adults, these tendencies will look like cloud cuckooland.

The most burning question for conservatives should be: What do we have to say to young adults and about the diverse world they are living in? Instead, conservative intellectuals seem hellbent on taking their 12 percent share among the young and turning it to 3.

Well, Continetti identified me with the Post-Liberal bloc because of the Benedict Option, though it’s kind of a catch-all category for people who doubt the liberal project. I don’t oppose pluralism; I see it as a social fact. I support immigration restrictions now, not because I oppose pluralism, but because we are in a cultural period in which figuring out how to stop, even reverse, social fragmentation is one of the most important political challenges facing the nation — and maintaining or increasing immigration is only going to make that worse.

It is true that the GOP, and the conservative movement more generally, has massive problems figuring out how to pass on its politics to the younger generations. The Millennials and Generation Z are much to the left of Gen Xers and Boomers — and are starting to vote in big numbers. I wonder, though, just how successful the Democratic Party, and the Left in general, is going to be once the Social Justice Warriors are in charge. The militant illiberalism, misandry, and racism of the emergent Left is going to send a lot of people over to the Right. When liberal intellectual Mark Lilla wrote a book saying that the Democratic Party — his party — needs to get away from identity politics and find a way to reach the white working class that broke for Trump, he was denounced as a white supremacist.

It’s true that the demographic shift, and the ethnic diversification of America, benefits the Democratic Party, but it is doubtful that white males will have a future in that party unless they are prepared to accept conditions of woke dhimmitude. The radical, identity-politics egalitarianism that began on campuses and has now spread more generally through the media and the culture of the Left fragments people along racial, gender, and sexual lines, and sets them at each other’s throats, in a way that the economic solidarity proposed by, say, a Mark Lilla would not. But then, he’s “making white supremacy respectable again.”

If any disillusioned Millennials or Gen Zers make their way to the right, what kind of Right will they find? I don’t understand what David would have the Right do, except be not-crazy leftists. Better a sane leftist than an ideological monster! But we need an actual Right-wing party in this country, though it must be conceded that simple demographic and ideological reality will push the GOP further to the Left in some ways, for the same reason Reaganism ended up pushing the Democrats out of their New Deal-Great Society paradigm, into Clintonism.

Still, it’s impossible to see what the GOP Establishment class has to offer anybody. Brooks’s frustration is born of the failures of that class. The fact that Trump does little but shout and lie doesn’t make the fusionist establishment (that is, national security hawks + free marketers + social conservatives) that Trump displaced any more credible or attractive. Matthew Walther says that the whole Ahmari-French fight is a tempest in a think-tanky teapot. Excerpt:

Consider what the fusionists have done so far. At the height of their influence under George W. Bush, the old fusionist conservatives managed to cut taxes once before the Iraq War cost Republicans their majority in the House of Representatives in 2006. It would be another decade before the GOP once again controlled the executive branch, the House, and the Senate. What did they do with their all-too-brief stranglehold on Washington? Cut taxes again.

On its face, this more or less accurate summary of the Republican Party’s thin résumé while in power reads more like an indictment of fusionism and its ambitions than anything else. It certainly is that. But it is also a reminder of how little regard national politicians have had for anything that does not enrich the wealthy. How many leaders of the GOP have come forward to celebrate the pro-life victories of their counterparts in state legislatures and governors’ mansions throughout the country? How many of them will say that they think Obergefell should be overturned? Wall Street and Hollywood have made their positions clear on everything from trade to abortion to China: It’s dollars all the way down.

This is not to suggest that the post-fusionist right cease all of its present activities and disengage from American public life. Politics is inevitable. So too for the foreseeable future are political defeats.

That’s true, but that was always going to be true as the country stumbles towards political realignment. The post-Clintonite Left may yet lose the 2020 presidential election, but that will only be one stumble on the road to a very different party.

As you know, the single issue that matters most to me is building a strong shield around religious liberty. I will never, ever forget learning in October 2015 that the House and Senate Republican leadership had no plans for post-Obergefell religious liberty legislation. None. They did not care. They didn’t want to be portrayed as bigots in the media, and heaven knows the donor class doesn’t care about us bigoted church people. Donald Trump, as bad as he is in so many ways, has been more pro-active on religious liberty protections than most any Congressional Republican would have been absent his presidency. Conservative religious believers can’t afford to forget that.

Ross Douthat has written the most important piece yet to help you understand the stakes of the Ahmari-French battle. He wouldn’t agree that it’s a minor skirmish among conservative intellectuals and writers. There’s something big being hashed out here. He says that it’s a fight between the old-school Right of the fusionists (represented by David French), and the rebellious Right sick of the old settlement; they are represented in this debate by Sohrab Ahmari.

(I should add that I joined Ahmari in putting my signature on a manifesto published a short time ago in First Things, saying that whatever the differences among the signatories, we all agree that after Trump, things cannot go back to where they were on the Right. My sympathies are firmly on Ahmari’s side in what you might call his philosophical diagnosis of the crisis. I don’t get the point of attacking David French, and I think French-ism — as Ahmari calls it — can’t be dismissed so easily. I’ve written about this in several earlier posts this week.)

Douthat’s contribution to understanding this dispute is in identifying what the Ahmarists want that separates them from the French fusionists:

A more assertive role for social conservatives within conservative coalition politics

A more active role for the state in the economy, to serve socially conservative ends

A philosophical consideration of where the liberal order has ended up

Douthat expands on that last point:

How radical that reconsideration ought to be varies with the thinker. Maybe it just means restoring some kind of lost conservative understanding of American institutions, as Yoram Hazony has argued in essays for First Things and the similarly post-fusionist journal American Affairs. Maybe it means questioning the philosophical underpinnings of the American founding itself, as Patrick Deneen argued in 2018’s big-think book “Why Liberalism Failed.” Maybe it means reinventing the Catholic anti-liberalism of the 19th century, and embracing the “integralism” championed by, among others, Adrian Vermeule of Harvard Law School.

The further this reconsideration goes, the more fanciful, utopian or revolutionary it might seem. (The integralists would cop to the last designation.) But the basic concept of a right rooted more in cultural conservatism and economic populism than in libertarianism and individualism isn’t fanciful; it describes the emergent right-of-center ideological formations all across the Western world. The American pendulum may swing back to fusionism after Trump — French is hardly alone in championing the old regime, and most Republican politicians remain instinctive fusionists — but some version of Ahmari’s turn is one that the right is making almost everywhere, for now.

Douthat points out the painfully obvious: that none of the dissident conservatives have figured out how to build any kind of coherent movement around the person of Donald Trump. Love him or hate him, Trump is such a polarizing figure that his person will determine our politics until he leaves the stage. Keep your eye on figures like Sen. Josh Hawley, who seems to be trying to figure out a philosophically coherent new conservatism from the fusionist ruins.

The most interesting aspect of the new conservatism is its skeptical attitude toward the Enlightenment. It’s not true to say that all the so-called Post-Liberals reject the Enlightenment entirely. Some may, but it’s more accurate to say that we are to various degrees Enlightenment-skeptical. It’s telling that the Fusionists treat this as heresy:

It seems to me that many of the Christian opponents of classical liberalism not only believe the following words to be false but to be actually destructive, over time, to public virtue and religious orthodoxy: pic.twitter.com/vtq2lbHmpT

— David French (@DavidAFrench) June 4, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

It’s a robust claim … but there’s truth in it. The argument is not settled by saying “how dare you?!” What if it turns out not only can liberal democracy not endure without grounding in stronger claims than “we hold these truths to be self-evident,” but also the particular features of liberal democracy — especially its project of emancipating the individual — serve over time to alienate citizens from the religious and social commitments they need to make liberal democracy work? We need to be able to talk about that without treating the Constitution like it is Holy Writ.

Though I was a signatory to the First Things statement, and though Continetti identifies me as a Post-Liberal, politics is only a secondary interest to my Benedict Option project. I see our entire political and social order disintegrating, much as the Western Roman Empire did in the 5th century. I’m not going to drag the argument out for you here, not after all this time, but basically the widespread decline of the Christian faith — both in terms of numbers, and in terms of elementary orthodoxy — is the greatest crisis of our civilization. The Benedict Option intends to address that. There is a political component to it, but the main thrust of the idea is not political. Whether the US is ruled by Republicans or Democrats is not ultimately important. That choice likely determines the rate of decline and fall, but not the fact thereof.

Bottom line: I’m interested in the survival of the Church, and in building resilient communities of traditional faith capable of resisting the disorders of the age, and bearing witness to a dark and chaotic time. Maybe even these communities will serve as the early Benedictine monasteries did: as strongholds of light, order, and channels of divine grace to a world in desperate need of same.

If we in the churches are going to build these communities, we need at some level to understand how the social, political, moral, and economic order we live under works against us. We also can’t be under the illusion that changing political leadership is sufficient to address the crisis. It may be necessary, but it is not remotely sufficient.

It should be said that it’s not only the Right that’s questioning the Enlightenment and its fruits in the classical liberal political order. The hatred with which many progressives regard First Amendment protections of free speech and religious liberty reveals that they believe equality (as they define it) is more important than liberty. Here is what I wish the Left understood about why so many of us Christians do not trust them with power. Alan Jacobs summarizes it well in this theoretical conversation on his blog:

Me: I’m concerned about the erosion of support on the left for religious liberty.

They: That’s a disgraceful calumny, we are passionately devoted to religious liberty.

Me: Only when you agree with, or at least are not offended by, the religious beliefs involved.

They: Another disgusting lie!

Me: So what do you think about that Masterpiece Cakeshop guy?

They: What a bigot! I hope the law comes down on him like a ton of bricks.

Me: But he says he’s acting out of his long-held religious convictions.

They: I despise it when people use religion to cover for their bigotry.

Me: So it’s like I said, you only support religious liberty when you agree with, or at least are not offended by, the beliefs involved — the ones you think are not bigoted.

They: Bigotry and religion are not the same thing! Religion is about a person’s relationship with whatever God they happen to believe in, it’s not about passing judgment on their neighbors.

Me: So having claimed the right to define what bigotry is, you’re now defining what religion is?

They: Look, you can go ahead and defend bigotry if you want to, but thank goodness there are laws against that in this country.

And with that, Your Faithful Correspondent, who has a wicked bronchial infection post-Walker Percy Weekend, is going back to bed. Y’all be good.

UPDATE: Reader BG writes:

Let me first say how much I appreciate this blog and all your efforts Rod. I want to add some thoughts here that explain why I think it’s so valuable, related to this issue:

I strongly agree with Matthew Walther’s take that this “storm” of controversy just DOES NOT MATTER, and that the Conservatism being fought over, in any of the described sects, is dead on the ground. Conservative thinkers and public figures are suffering from the same navel-gazing they so often accuse liberal journalists of. They may think they are out of the bubble, but they are still in it. All the issues and tactics they are giving so much thought and prose to matter almost nothing to most millenial (and Gen-X) voters. The Blue Wave isn’t just coming. It’s already here, having tsunami’d over the younger generation; the older generation just doesn’t realize it yet.

When I watched Trump pull off his surprise election victory in 2016, I remember two distinct thoughts coming to me, seemingly reflexively:

1) Wow, that was unexpected.

2) This is the dying gasp of an America that doesn’t exist anymore.

Conservative thinkers like to talk about Trump as though he’s a new direction for the movement. But there’s no new direction, because the moving volume has no mass. Statistically speaking, almost no one under 35 has a strong affinity for any of these brands of conservatism. And this is what makes the Benedict Option so critical to those of us still trying to raise families.

I’m a 30-year-old Christian conservative with a young family. I attended a private Christian college, in one of the reddest states in the country one with an emphasis on Apologetics and the Western Cultural Tradition. I would say more than 80% of its student body were what you would call “serious Christians”, and probably more than half would call themselves conservative. I graduated 8 years ago. In that time, among my peers from school, I’ve noticed:

-roughly half have stopped attending Church altogether

-more than half half are fully-affirming LGBTQetc “allies”

-more than half openly despise Trump and the GOP

-maybe 20% are already divorced

-more than ~25% had a child (or children) before they were married

-at least half believe the Green New Deal is the only hope for humanity’s future

-almost all of them are completely dependent on social media for their intellectual formation

Earlier this week, a close friend of mine from school came out to me as Transgendered. He (she?) was a leader on multiple mission efforts during our time as students. Another good friend of mine, who graduated as a Divinity student, is now an open advocate for more acceptance of human-animal relationships.

Now, keep all this in mind, and remember that this is a representative sample of what should be the MOST CHRISTIAN/CONSERVATIVE portion of the electorate. Religious/political affiliations with the “movement” decline logarithmically from there.

All this is to say that I very much appreciate the intellectual stimulation that the conservative thinkers provide. But they are playing a game with themselves. As Michael Anton said in his “Flight 93 Election”, “we are headed off a cliff”. I’m no saint, but I do feel very, very alone as a conservative Christian man trying to raise a faithful, thoughtful family in 2019. Our church is devout and fervent, but shrinking. Many of my friends would disown me if they knew the extent of my political beliefs. My wife, an extremely social person, found herself to be the only woman among her many peers that was skeptical of the Kavanaugh accusations. Thank God, we found a good classical Christian school nearby that we can save up for for our kids. The Benedict Option shouldn’t even be a debate anymore; the great deluge of secular Leftism isn’t coming in 2020 or 2024, it’s here NOW.

UPDATE.2: Reader PW:

I am a millenial. Let’s get down to brass tacks. Here are my top concerns in my day-to-day life:

1) The endless spiraling costs of healthcare. This is CRITICAL to young families, and something the SoCons seem constitutionally incapable of even talking about honestly.

2) Student loans. I spend as much on student loans as I do for food for a family of four. This expense cripples my family.

3) Housing costs. For those of us not in flyover country this has hit a critical point.

4) Childcare / education. As a family, this actually *exceeds* my housing costs.

5) Wages. Wages in my industry have been flat for 20 years, and I work in a “good” job!

Republicans have nothing – in fact, less than nothing, to offer me. All the SoCons seem constitutionally capable of doing is screaming about a flag somewhere. I cannot express how little that matters to me.

In my bones, I’m not really in line with the current Democrat party. I’m fiscally to the *right* of the Republican party (talk about irresponsible, modern Republicans never met a budget they couldn’t blow out). I’m socially close to Dreher.

And every year, the Republicans push me further and further into the Democrat coalition. The utter corruption of the Republican Party is breathtaking in it’s thoroughness. That corruption makes it utterly unable to respond to the concerns of anyone who isn’t a billionaire or a farmer in a narrow swing district.

The fact of the matter is, Republicans have made it clear: they have no interest in me, and they are not getting my vote.

Advertisement

June 3, 2019

Ahmari-French 4-Ever

Lots of takes on Ahmari-versus-French to think about. I appreciate this discussion, because it’s forcing me to think harder about my own position, or positions. And it’s rather revealing about where others stand.

Stephanie Slade, writing in Reason, says that Team Ahmari is neither conservative nor Christian. Excerpt:

Classical liberal values and institutions offer a robust bulwark against the worst excesses of the illiberal left. Do Ahmari et al. actually think the system that gave us the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby ruling is so broken as to justify setting the whole thing ablaze? More to the point, do they really believe that what follows after the smoke clears will be better for religious traditionalists?

Yes, exactly. But then Slade goes off the deep end:

But the First Thingsian rejection of the liberal order isn’t merely strategically imprudent. It’s morally reprehensible from a Catholic perspective. The dignity of the human person, which follows from our being created by God in His image and likeness, demands that we be given expansive freedom to make choices for ourselves.

That’s not libertarian propaganda. It comes straight out of the Catechism (“God created man a rational being, conferring on him the dignity of a person who can initiate and control his own actions”), which in turn quotes the Bible (“God willed that man should be ‘left in the hand of his own counsel,’ so that he might of his own accord seek his Creator and freely attain his full and blessed perfection by cleaving to him”). As the economist Eric Schansberg once wrote of Adam and Eve, “It was not God’s plan that they should sin, but it was God’s will that they should have the choice.” To exercise coercive control over a person is to treat him as undeserving of a gift bestowed by his creator. It’s to place yourself above your creator.

Whoa, whoa, whoa. You cannot say that the apex of Roman Catholic political thought was reached in Mill and Locke, and that it is “morally reprehensible from a Catholic perspective” to reject it. Where does one even begin with that? Just like that, the entire non-liberal conservative tradition is dismissed as not only unconservative, but un-Christian! That’s so silly it scarcely rises to the level of offensive. This is well into the “God is love, so therefore Christians have to approve of gay marriage” territory. I expect libertarians to strongly oppose anything Team Ahmari says, but calling it “unconservative” and even “un-Christian”? No.

Where I doubt Team Ahmari is that the kind of political order they desire is even possible in pluralistic, post-Christian America, in a way that it is not in, say, Hungary and Poland. Whether it’s desirable is, to me, a secondary question, or at least merely a theoretical one. But the claim that secular liberalism is the only political order consonant with Christianity — and Catholic Christianity at that! — is risible.

Matthew Continetti offers a taxonomy of the various positions and people on the contemporary American Right. He pus my TAC boss Johnny Burtka in the Paleo category, but I end up in a different slot. Continetti writes, in part, about the Post-Liberals:

Here is a group that I did not see coming. The Trump era has coincided with the formation of a coterie of writers who say that liberal modernity has become (or perhaps always was) inimical to human flourishing. One way to tell if you are reading a post-liberal is to see what they say about John Locke. If Locke is treated as an important and positive influence on the American founding, then you are dealing with just another American conservative. If Locke is identified as the font of the trans movement and same-sex marriage, then you may have encountered a post-liberal.

The post-liberals say that freedom has become a destructive end-in-itself. Economic freedom has brought about a global system of trade and finance that has outsourced jobs, shifted resources to the metropolitan coasts, and obscured its self-seeking under the veneer of social justice. Personal freedom has ended up in the mainstreaming of pornography, alcohol, drug, and gambling addiction, abortion, single-parent families, and the repression of orthodox religious practice and conscience. “When an ideological liberalism seeks to dictate our foreign policy and dominate our religious and charitable institutions, tyranny is the result, at home and abroad,” wrote the signatories to “Against the Dead Consensus,” a post-liberal manifesto of sorts published in First Things in March.

“The ambition of neoliberalism,” wrote the editor of First Things in the spring of 2017, “is to weaken and eventually dissolve the strong elements of traditional society that impede the free flow of commerce (the focus of nineteenth-century liberalism), as well as identity and desire (the focus of postmodern liberalism). This may work well for the global elite, but ordinary people increasingly doubt it works for them.” The result, he said, has been populist calls for the “strong gods” of familial, national, and religious authority.

The post-liberals are mainly but not exclusively traditionalist Catholics. Their most prominent spokesman is Patrick J. Deneen, whose Why Liberalism Failed (2018) was recommended by that ultimate progressive, Barack Obama. Israeli philosopher Yoram Hazony’s Virtue of Nationalism (2018) is another important entry in the post-liberal canon. Hazony has contributed essays to both First Things (“Conservative Democracy”) and American Affairs (“What Is Conservatism?”) making the case for conservatism without Locke, Jefferson, and Paine.

The post-liberals have put forward two contradictory political strategies. The first, advanced by Rod Dreher, who is Eastern Orthodox, is the Benedict Option of turning away from the secular world and shielding, as best you can, spiritual life. The second, as put by Sohrab Ahmari also in First Things, is “to use these values [of civility and decency] to enforce our order and our orthodoxy, not pretend that they could ever be neutral.”

I would tweak this slightly. Sohrab’s strategy is explicitly political. My strategy is only incidentally political; it is pre-political, in that it is primarily spiritual and cultural. I’ve explained at length why I strongly sympathize with Sohrab — it’s fair to call us both Post-Liberal — but can’t agree with his political strategy. (In part because I’m more pessimistic than he is.) Along these lines, the Thomist philosopher Edward Feser has some interesting words about the Ahmari-French debate. Excerpts:

If anything, Continetti understates the grounds for pessimism about the prospects for a post-liberal conservative politics. For contemporary Western society is radically out of step with the basic premises to which the post-liberal conservative is committed. Indeed, I would say that liberalism is a Christian heresy and one that seems now to be approaching its full metastasization. I would say that it is the moral and political component of the broader heresy of modernism, which is at high tide and sweeping all before it, the flood now having penetrated deeply into even the innermost parts of the Church. It is like Arianism both in its breathtaking reach and in its longevity. It is worse than Arianism in its depravity. Its god is the self – the sovereign individual of the liberal, and the subjective religious consciousness of the theological modernist – and in seeking to conform reality to the self rather than the self to reality, it tends toward subjectivism, relativism, fideism, voluntarism, and other forms of irrationalism. And there is no limit to the further errors that might follow upon such tendencies. That is why, as Pope Pius X said, modernism is the “synthesis of all heresies.”

Because of this irrationalism, the liberal and modernist personality tends to be dominated by appetite, and by sexual appetite in particular, since the pleasures associated with it are the most intense. But he also has a special hostility to the natural purpose of sex – marital commitment, children, and family – because that imposes the most stringent obligations on the self. The family is also the fundamental social unit, and thus the model for all other social obligations, such as those entailed by ties of nationality. Hence it is inevitable that the liberal and modernist personality will seek to reshape the family, and through it all social order, to conform to his desires. Woke socialism is the last stop on the train ride that begins with radical individualism.

Some readers will no doubt find all of that overwrought, to say the least. The point, however, is that it is a diagnosis that is hard to avoid if one begins with the sorts of premises to which post-liberal conservatives are typically committed. And it entails that an ambitious near-future post-liberal conservative political program is probably not feasible, precisely because, as Continetti says, there simply are not enough voters who still sympathize with that view of the world. In the short term, it seems to me, the post-liberal conservative will have to settle for rearguard actions, piecemeal and often only temporary victories, uneasy alliances with other conservatives, and in general a strategy of muddling through that can hope at best to take the edge off the worst excesses of late stage liberalism.

Where he must be ambitious is in working for the long term revival of Western civilization. For the average person, that means committing oneself firmly to a countercultural way of life – to religious orthodoxy, to having large families, and to preserving the social and cultural inheritance of the past the best one can at the local level, Benedict Option style. For the intellectual, it means working to revive the classical (Platonic, Aristotelian, Scholastic) tradition in Western thought, and showing how it is not only in no way incompatible with, but provides a surer foundation for, the good things that modernity has produced (such as modern science, limited constitutional government, and the market economy).

The good news the post-liberal conservative can give the fusionist is that rejecting liberal philosophical foundations does not entail rejecting these good things, even if it does mean interpreting or modifying them in ways that the fusionist might not like. The bad news is that philosophical liberalism has so eaten away at the moral foundations of Western society that these good things too are threatened along with everything else.

Strongly suggest reading the whole thing. Feser is onto something important. A smart Christian cultural observer told me today, “American Christians, with a tiny handful of exceptions, have no means of self-defense, nothing, nil, nada. They are completely at the mercy of the culture, and completely in denial about it.” This friend is not a Trumpist, nor a Never Trumper. His comment is about the dissolute state of Christian culture in late liberalism.

David French (MTP screenshot)

Jake Meador criticizes Team Ahmari harshly in this post. He goes too far, I think, but here’s the part I liked:

“What, then, of political power?” you might ask. Does not the above represent little more than yet another twist on Anabaptist style quietism, a refusal to get one’s hands dirty in the necessary and inevitably messy work of politics?

It does not. Rather, it recognizes that a genuinely Christian political witness is not merely about a certain political content in our ideas, but a particular mode of existing as political beings. To become intelligible to those whose only political standard is the acquisition of power is to give up any political good other than power. It is, then, to give up our quiet confidence that God is at work in the world and that his work will not be advanced by those of us who would eat the king’s food and bow to his idols.

It is only candor that our foes do not understand, Berry reminds us, an inner clarity that comes from knowing that there are goods in this world grander than political power and fates in this world more dark than martyrdom.

I found myself wondering what stance Jake would take if he were a Spanish Catholic of the 1930s, when there was no middle ground, and you had either to stand on the side of the Nationalists (that is, with Franco) or with the Republicans, violent anti-clericals who burned down churches and the like. I hope to God that none of us American Christians every have to make a choice like that. But we might. We are not Spain in 1931, but I am much less put off than Jake is by Ahmari’s alarmist rhetoric (though to be fair, Jake grew up in a fundamentalist church, and was traumatized by it; Sohrab’s rhetoric sets off his anti-fundamentalist spidey sense). In my experience, you can shout at most conservative American Christians that the river is rising, and they had better get out before the flood takes them, and they will do their very best to deny the radical nature of the threat. They are so bought into the idea of Christian America, and the American project, that they have no choice but to live in denial. If maintaining one’s commitment to shoring up the Empire requires lying to oneself about the realities in which we all live, then they’re prepared to do that, because the alternative is too hard, too scary.

I get that. I really do. It is hard, and it is scary. But what are the realistic alternatives? Last summer, I wrote a post about re-reading The Final Pagan Generation, historian Edward Watts’s account of the intellectual and cultural world of learned Romans born at the beginning of the 4th century, during which the Roman Empire became officially Christian, and pagan religion withered. (As did the Roman Empire, nearly concurrently.) From that post:

Interestingly enough, despite all this, most pagan temples in the Empire remained open, and images of the pagan gods were still ubiquitous in Roman cities. Pagan festivals continued to be observed. Writes Watts, despite the anti-pagan laws, “traditional religion remained very much alive throughout the empire.”

We now know from history that the fourth century was when the Roman world changed fundamentally, and became Christian. But that’s not how it appeared to members of the final pagan generation, at the end of that century, and their lives. Here’s how Watts’s book ends:

The fourth century has come to be seen as the age when Christianity eclipsed paganism, and Christian authority structures undermined the traditional institutions of the Roman state. Modern historians have highlighted the rising influence of bishops, the emergence of Christian ascetics, the explosion of pagan-Christian conflict, and the destruction of temples. This is one fourth-century story, but it is neither the story that the final pagan generation would have told nor the one that later generations told about them. Their fourth century was the age of storehouses full of gold coins, elaborate dinner parties honoring letter carriers, public orations before emperors, and ceremonies commemorating office-holders. These things occurred in cities filled with thousands of temples, watched over by myriads of divine images, and perfumed by the smells of millions of sacrifices. This fourth century was real, and the men who lived through it told its story in ways that mesmerized later Byzantine and Latin audiences.

What are the lessons I draw from all this for Christians in our own time? Let’s stipulate that the world of 21st century Europe and North America is very different, in obvious ways, from that of fourth-century Rome. But there are parallels.

Christianity today is like traditional religion of the fourth century. We are at the end of the Christian age, not at its beginning. Christianity back then had muscle. It is now decrepit, as a social force. The fact that we Christians believe that our faith is true can blind us to the fact that what is obvious to us is by no means obvious to others.

It is not clear what the Roman pagans could have done to have slowed or stopped Christianity, but it is quite clear, in retrospect, that they did not take it seriously enough as a threat. This was a failure of imagination on their part. They assumed that the world would always be as it was, because it always had been.

Worldly power matters. If Constantine had not converted, the future of Christianity in the West would have looked different.

Yet worldly power is limited. Julian the Apostate failed miserably. You cannot legislate belief.

Talented elites who form, and who are formed by, a counterculture, can have an outsized effect. Bishops and priests who saw their function as to serve the imperial system were not as inspiring to the young as those who rejected it, and its promises.

The old ways of resisting anti-religious forces — fighting within the system — don’t work. This makes me doubtful about the strategy that people like me have generally adopted: fighting within liberalism for liberal goals, like religious liberty. The asymmetrical strategies of opponents, like LGBT rights groups, overwhelm us. But what can we do?In the main, the story of the final pagan generation ought to be a severe warning to us complacent 21st century Christians. Ours is also a time of “storehouses full of gold coins, elaborate dinner parties honoring letter carriers, public orations before emperors, and ceremonies commemorating office-holders.” Christians are complicit in all of these. But the deeper shifts in the culture are clear for those with eyes to see. The old religion — Christianity — is fast fading. The young believe in a new religion of self-worship, hedonism, and materialism. The laws are not yet anti-Christian, but the broader culture is moving to push Christianity to the margins quickly. This is not likely to change. Christians need to prepare for this.

By “prepare for this,” I mean several things, all of which can be summed up with: Stop the complacency. Details:

Stop thinking that it’s always going to be this way, and that anything short of radical action is sufficient. The mindset of older Christians may actually be a hindrance, because they don’t understand how radically different the world today is.

Do not mistake the presence of Christian churches and symbols in public life for the true condition of Christianity in the hearts and minds of people. Remember, the pagan temples and statues of the gods remained long after paganism was a dead letter.

Clean up our own churches. Stop tolerating corruption within the church — especially corruption that benefits the leadership class, at the expense of the church’s authority and integrity. Watts presents no evidence that pagan temples were corrupt. I bring this up simply to point out that Christians are in an existential fight, and cannot afford to have our own positions weakened by internal corruption.

Train ourselves and our children to stand aside from the promises of the world, and to cultivate asceticism, like the elite Christians of the mid-fourth century did. Only then will we develop the heart and the mind to resist.

Understand that we, like the final pagan generation, might think we are fighting for tolerance, but our opponents are fighting for victory. We have to change our tactics. We are bad at asymmetrical warfare. Frankly, like an old pagan of the fourth century, I would prefer to fight for tolerance — but that is not the fight that’s upon us.

Neither abandon politics entirely, nor put too much faith in princes. Elites cultivated relationships within the imperial power structure, and served that power structure. But the real work of conversion happened among the people, through the labors and examples of saintly ascetics and charismatics.

Read the whole post, which summarizes the Watts book. Look at point 5. Is that not Ahmarist? Did I see things more clearly when I wrote that? I wonder: if we’re not fighting for tolerance, what are we fighting for? Is it an achievable goal? Or: which goals are achievable, and which ones not? Do I need to read The Final Pagan Generation a third time to re-learn?

Advertisement

Incels & Socialism

A comment from a reader:

As a millenial male whose conservative Catholic identity is currently breaking away piece by piece, I take interest in this issue. For an involuntarily celibate humanities casualty in the economic wasteland of the California interior, making below minimum wage online and being driven to mass by his parents, the entire Benedict Option debate seems like the luxury of those who can afford to form families to protect.

I became Catholic three years ago. I quickly gravitated to the Latin mass because I love the exotic beauty of the language and the sacredness of the music. But over time I realized that in both pre- and post-VII Catholic communities, the entire culture of the faith is oriented around three groups: priests, religious, and married parents. I don’t have a vocation to be a priest (and in any case take antidepressants), I can’t join a monastery because of my student loan debt, and I lack the sexual-economic marketability to become a parent. The plight of the involuntarily single male is overlooked in the Catholic discourse; it’s viewed as an unnatural state, a peculiarity. The church spends tremendous energy advocating the unborn and extolling family life, but does little to actually promote family formation.

Where is the church helping me find a job and a mate? I sympathize with gainfully employed family men such as Ahmari and French and their desire to preserve Christian family values, but what do Christian family values mean to me if I am shut out from family life, perhaps permanently? Traditionalist conservatives only seem to care about people with families. I know this isn’t actually the case, but it is true that their discourse is heavily accented on those with the economic fortuity of having a family.

I haven’t gone to church in three weeks. The underlying cause of my disillusionment was the frustration described above, but it was precipitated by my disgust with the church’s position on abortion in case of maternal life endangerment, which I could no longer accept after Alabama included this exception in its law. I was also embittered by the plight of a friend whose wife divorced him against his will; if he had had a Catholic wedding, the church would say tough luck, he can’t remarry.

No longer keeping the faith, I am tempted to affiliate myself with socialism. The techno-plutocracy isn’t going to get any more humane as the march of automation concentrates the wealth and the jobs in the hands of ever fewer people. I am a default conservative on marriage, abortion, and immigration, but I am willing to overlook these issues if the Sanderses and Ocasio-Cortezes of Congress are truly prepared to make life more dignified for unemployed and underemployed young people.

Rod, I have great respect for you and enjoy your blog, so please don’t simply dismiss this comment as incel raving. You recently wrote a very respectful and compassionate post about a young conservative who embraced Islam. Please show the same compassion for young conservatives tempted by socialism.

I’m not going to make fun of this guy. He’s desperate, and his desperation is not something to mock. When I was researching the Sovietization of Eastern Europe earlier this year, I discovered that the mass loneliness, displacement, and aimlessness of young men in postwar Eastern Europe played a significant role in the establishment of Communism there. Of course the Red Army played the largest role, but there were people who were hungry for what Communism had to offer, because everything was broken, and they longed for solidarity and stability.

If you have something serious to say to this young man, let’s hear it. If you’re only going to make fun of him, don’t bother, because I won’t publish it. I have been hearing from too many unhappy single people lately, and have been frustrated by my inability to help them, to tolerate poking fun at what they’re suffering. All they’re asking for is the kind of things that most people have always taken for granted: a spouse and a family. Neither the Church nor the State can find him a spouse, but that longing is sooner or later going to make a connection with something.

UPDATE: This e-mail came from a reader who is an observant Catholic in his 30s, married with children. I’ve taken out other identifying details. I think he’s 100 percent correct here:

I find myself in agreement with almost everything you post; I think the Benedict Option is a no-brainer; I believe religious liberty is already significantly curtailed in the public sphere; I have no doubt that a person like me is anathema to cultural elites; and I am strongly skeptical that there is a legislative or political path towards a more friendly, plural, tolerant equilibrium.

So, let me try to put in words what I felt the urge to share. Basically, I’m increasingly worried about what comes next for masculinity given the current state of affairs, but it isn’t socialism that is concerning me. It’s fascism.

In the particular case of your young millennial incel correspondent, his interest in socialism is either going to be stable and anodyne — great, another boring white ally to the left who reliably votes Democrat, big whoop — or dramatic and short lived: I can’t see any actual socialist organizations, or far left groups, being a friendly home to a dude like this. I’m not going to make fun either, because there but for the grace of God go I, but he’s not their target demographic and will be unlikely to form meaningful bonds with any of those communities.

But you know what is a really friendly home to a dude like this? The white nationalist far right, online and offline. Based on a cursory review of photos and videos from the Charlottesville marches and similar events, the current movement strongly over-indexes on incels and their ilk. If the primary draw to Catholicism was the exotic beauty of the Latin and the sacredness of the music, then I can’t help but think the pomp, regalia, and tradition of national socialism will also resonate.

This is a single case, but I think there’s a broader truth to this. Young men (like me) have come of age in an environment where the dominant view is that straight white maleness is the problem, and where their economic prospects and likelihood of being able to develop a stable and loving family in a community oriented towards that family’s success are both worse than they ever should be. Your correspondent self-identifies with a label that comprises overwhelmingly white, virulently racist and misogynist young men who are already glorifying radical violence. This isn’t a good set of identifiers for what could be a very large constituency.

SJWs and the far left aren’t capitalizing on this growing disaffection: in fact, they are making it worse. I’m not sure the far right is capitalizing on it yet either, at least to an extent that we should be worried, but it’s only a matter of time before someone is able to effectively communicate to this group and say you know what, you’re right to feel aggrieved and you’re right to hate the people who’ve taken your prospects from you. You’ve been told that your identity is the problem, but really it’s the thing that we can build a movement on. SJWs and libs have prevented you from having what is dutifully yours: respect, a meaningful role in society, a family. Sorry, let me rephrase that. The far right is already implicitly and explicitly doing this; I just don’t think they’ve been able to do it to the scale they could yet.

So while I agree with 99% of your writing, to think about this as an issue of Incels and Socialism is to miss the forest for the tree. There’s a whole lot of disaffected young white men out there just like your correspondent, and they aren’t going to become SJWs in service of a radical left agenda. They are perfect recruits for a radical right, hate-based movement that will tell them to embrace their grievances, and give them a way to get back at the institutions and individuals that held them down for so long.

More broadly, I guess what motivated me to write is the tension I feel as a young white male who also tries to be an orthodox Christian. On one hand, I know that if I were to clearly and unequivocally state my beliefs about gender ideology I would lose my job. On the other, I know that the disaffection that got Trump elected is putting people like me on a path to nowhere good.

Advertisement

More Ahmari-French Fighting Words

Let’s get back to the Ahmari vs. French argument, shall we? My first set of comments about it are here. I do not agree at all with the conservatives who have said it’s bad for conservatives to argue in public. To the contrary, we need to have this argument. It should not be policed by other conservatives. I do object to how needlessly personal Ahmari made it with his initial post, but there is genuine substance to their dispute.

Commenter Rob G. says:

“To my mind, this dispute reinforces the merits of Deneen’s conclusion in Why Liberalism Failed: rather than lay out some grand post-liberal politics, Deneen recommends communal, counter-liberal forms of life. The intelligentsia tends to invest too much energy in imagining what the ideal political order would look like; the New Testament is much more concerned with how we should live faithfully in the midst of the unjust political orders in which we find ourselves.”

I noted this same sort of thing going on in some of the criticisms of The Benedict Option, as if these critics couldn’t move forward on it without some sort of program or other to guide them. In many cases it seemed to be simply an excuse for not doing anything at all.

Yes, it’s as if they would only accept a diagnosis that led them to a particular set of go-and-do conclusions. I was talking yesterday with a Christian friend, who observed that the Christian world is full of people who have given no substantive moral and spiritual foundation to their children because they don’t have any themselves. They have been part of feelgood churches, however conservative (and yes, conservatives can have feelgood churches too), and perhaps have trusted in the fact that in their family, they hold correct opinions, therefore all will be well. Then their kids drift away from faith, caught in the inexorable currents of liquid modernity. They can’t figure out why.

I completely share Ahmari’s rage at the sheer destructiveness of left-progressive culture, but I don’t believe there is a political solution for it. Some on the Christian Right call me a “defeatist” for holding this view. I think they are at best naive idealists, and at worst grifters.

Jim Geraghty at National Review has a piece up today detailing how certain right-wing people and groups — he names names — support their lifestyles by ripping off grassroots conservative donors, telling the rubes that they (the grifters) are the only thing standing between the liberal mob and the marks. Decent people at the grassroots give their money, and … nothing happens. As Geraghty shows, a lot of these grifters and their PACs pocket the money, and then keep exploiting the deterioration of the culture to separate conservatives from their cash.

But Grifter Cons are not the main problem. The main problem is that there is no political solution because most Americans simply no longer are on the side of social and religious conservatives. I was just up in my hometown over the weekend. It’s Mayberry, RFD. Trump won the parish in 2016 with nearly 60 percent of the vote (if the black vote had been discounted, I imagine Trump would have won 90 percent of the vote). I learned over the weekend that they also have gay couples going to high school prom together, and transgender kids in the local school. You can say this is progress, you can lament this as decline, but what you can’t do is pretend that it’s not here, and it’s everywhere.

Here’s a reminder from The Benedict Option about the state of the culture among people who identify as Christians:

As bleak as Christian Smith’s 2005 findings were, his follow-up research, a third installment of which was published in 2011, was even grimmer. Surveying the moral beliefs of 18-to-23-year-olds, Smith and his colleagues found that only 40 percent of young Christians sampled said that their personal moral beliefs were grounded in the Bible or some other religious sensibility. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the beliefs of even these faithful are biblically coherent. Many of these “Christians” are actually committed moral individualists who neither know nor practice a coherent Bible-based morality.

An astonishing 61 percent of the emerging adults had no moral problem at all with materialism and consumerism. An added 30 percent expressed some qualms but figured it was not worth worrying about. In this view, say Smith and his team, “all that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life.”

These are not bad people. Rather, they are young adults who have been terribly failed by family, church, and the other institutions that formed—or rather, failed to form—their consciences and their imaginations.