Rod Dreher's Blog, page 226

July 14, 2019

Busing Or Bust

Wow, wow, wow. The Progressive-Industrial Complex is really going to do this thing. Trump could dump Pence and pick Jeffrey Epstein as his running mate, and still win because half of America + 1 is going to be terrified of the social engineers of the Loony Left. pic.twitter.com/dEMo9NnYcZ

— Rod Dreher (@roddreher) July 12, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

I see that this tweet ‘o mine has stirred up progressives on Twitter. Of course. Fine by me, but man, those people really and truly cannot grasp the damage they’re doing to themselves.

Are we really going to re-argue about school busing? Apparently so. Of all the things to get wound up about, and to make an issue in the 2020 presidential race, defending the virtues of one of the most unpopular public policy initiatives of the past 50 years is not one I expected from a party that wants to defeat Donald Trump. But this is how our progressives roll.

The other day, AOC more or less called Nancy Pelosi racist because the 79-year-old legislator dared to question whether or not AOC and her Democratic cohorts were following the wisest course for the party. But you know how these progressives are: if you don’t agree with them 100 percent, then you are Evil. It’s idiotic and self-defeating, but as someone who would rather not see these loonies in power, I guess I should be happy about it. Maureen Dowd actually had a pretty good column about it today. She writes:

Pelosi told me, after the A.O.C. Squad voted against the House’s version of the border bill and trashed the moderates — the very people who provided the Democrats the majority — that the Squad was four people with four votes. She was talking about a legislative reality. If it was a knock, it was for abandoning the party.

That did not merit A.O.C.’s outrageous accusation that Pelosi was targeting “newly elected women of color.” She slimed the speaker, who has spent her life fighting for the downtrodden and who was instrumental in getting the first African-American president elected and passing his agenda against all odds, as a sexist and a racist.

A.O.C. should consider the possibility that people who disagree with her do not disagree with her color.

The young lawmaker went further, implying that the speaker was putting the Squad in danger, asking why Pelosi would criticize them, “knowing the amount of death threats” and attention they get. Huh?

A.O.C. pulled back and said she wasn’t calling Pelosi a racist. But once you start that ball rolling, it’s hard to stop. (You know how topsy-turvy the fight is when the biggest defenders of Pelosi, who has endured being a caricature of extreme liberalism for decades, are Trump and the Wall Street Journal editorial board.)

If you haven’t read the excellent James Lindsay/Mike Nayna analysis of the religion of Social Justice, now’s a good time. Relevant excerpt:

Applied postmodernism begins in postmodernism, which as a social philosophy bears the following axioms, treated as articles of faith, as succinctly (and charitably) summarized by Connor Wood:

Knowledge and truth are largely socially constructed, not objectively discovered.

What we believe to be “true” is in large part a function of social power: who wields it, who’s oppressed by it, how it influences which messages we hear.

Power is generally oppressive and self-interested (and implicitly zero-sum).

Thus, most claims about supposedly objective truth are actually power plays, or strategies for legitimizing particular social arrangements.

So, among the SJW school of progressivism, to question the claims of a high-status person in the hierarchy of Oppression is to deny that those claims have any validity, which really means that you are denying the identity of the grievance-bearer.

The op-ed essay in question was written by Nikole Hannah-Jones, who is black. In it, she takes Sen. Kamala Harris’s side on the busing question, and slams Sen. Joe Biden as a fellow traveler of segregationists:

That we even use the word “busing” to describe what was in fact court-ordered school desegregation, and that Americans of all stripes believe that the brief period in which we actually tried to desegregate our schools was a failure, speaks to one of the most successful propaganda campaigns of the last half century. Further, it explains how we have come to be largely silent — and accepting — of the fact that 65 years after the Supreme Court struck down school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, black children are as segregated from white students as they were in the mid-1970s when Mr. Biden was working with Southern white supremacist legislators to curtail court-ordered busing.

The essay is actually well worth reading — seriously. Here’s what’s hard to understand, though, in that paragraph. If it’s true that “black children are as segregated from white students as they were in the mid-1970s,” then in what sense was busing not a failure? I guess Hannah-Jones means it was succeeding at its goal, until people (white people) decided they didn’t want their kids to go to school with black kids, and therefore declared that busing had “failed.”

She writes:

Like Kamala Harris, I was one of those kids bused to white schools. Busing was part of a dsegregation plan Waterloo, Iowa, adopted using federal desegregation funds after being sued by the NAACP. Starting in second grade and all the way through high school, I rode a bus two hours a day. It was not always easy, but I am perplexed by the audacity of people who argue that the hardship of a long bus ride somehow outweighs the hardship of being deprived of a good education.

No, black kids should not have to leave their neighborhoods to attend a quality school, or sit next to white students to get a quality education. But we cannot be naïve about how this country works. To this day, according to data collected from the Education Department, the whiter the school, the more resources it has. We cannot forget that so many school desegregation lawsuits started with attempts by black parents to simply get equal resources for black schools. Parents demanded integration only after they realized that in a country that does not value black children the same as white ones, black children will never get what white children get unless they sit where white children sit.

I have spent most of my career chronicling the devastating effects of school segregation on black children. I have spent days in all-black schools with no heat and no textbooks. Where mold runs dark beneath the walls and rodents leave droppings on desks for students to clear in the mornings before they sit down. Where children spend an entire school year without an algebra teacher and graduate never having been assigned a single essay. And then I have driven a few miles down the road to a predominately white school, sometimes within the same district, sometimes in an adjacent one, and witnessed the best of American education. This is not to say that no white children attend substandard schools. But if there is a black school nearby, it is almost always worse.

The black students I talk to in schools that are as segregated as the ones their grandparents attended know it is like this because we do not think they deserve the same education as white children.

This is a choice we make.

The same people who claim they are not against integration, just busing as the means, cannot tell you what tactic they would support that would actually lead to wide-scale desegregation. So, it is an incredible sleight of hand to argue that mandatory school desegregation failed, while ignoring that the past three decades of reforms promising to make separate schools equal have produced dismal results for black children, and I would argue, for our democracy.

Before I write anything else, let me point out a couple of things. I was born in 1967, in a rural Southern parish where the population was (slightly) majority black. My generation was the first to attend integrated schools from the beginning. There was only one elementary school and one high school for the entire parish. Because it was a rural place, with a widely dispersed population, many of us rode the school bus for an hour or more each day. I did, because my mom drove the bus. “Busing” in the sense we’re talking about here did not exist in the integrated public school system I attended.

Now, nobody can doubt that school segregation was unjust, and that black schools received far fewer resources than white schools. “Separate but equal” was not only immoral, it was a lie. Segregation had to end.

The question here, though, is whether the end of segregation should have meant the end of laws mandating segregated schools, or whether it should have mandated positive actions meant to de-segregate school systems. The answer federal judges in the 1970s gave was: desegregation. Hence busing. It seems to me that Hannah-Jones is correct to say that people who oppose busing don’t have anything to offer regarding strategies for desegregating schools.

What she’s ignoring, though, is whether achieving desegregation (as distinct from ending segregation) was worth the political and social cost. She assumes that it was, and that the only reason busing failed was because racist whites wanted to keep their kids from going to school with black kids. Let’s acknowledge that there were plenty of racist whites who flat-out didn’t want their white kids studying with black kids. Shame on them. It’s impossible to watch this 1974 footage from anti-busing protests in Boston and to think that they were only motivated by civic concern, not racism.

But it’s also hard to watch it and think that race hatred explains everything. There’s a white woman in those clips — clearly white working class — who says it’s not fair that her kid can’t go to school at the school across the street, and instead has to be bused across the city. Why is she wrong to be upset by that? Wouldn’t a black parent be similarly upset? The busing-and-desegregation story is more complicated than the simplistic black-white dichotomy.

For one, if Hannah-Jones’s narrative is true, then there could have been no legitimate moral reason for white parents to resist busing. Wanting your kids to go to school in their neighborhood — nope. Wanting your kid to go to school in their neighborhood because you, as a parent, can be more involved there — nope. These are all covers for racism, in the Hannah-Jones view. Or at best, these reasons do not outweigh the moral requirement to achieve desegregation. In other words, reaching racial balance in public schools was such an overwhelming moral imperative that nothing legitimately stands in its way.

The education scholar Stuart Buck — a white man who is the adoptive father of two black children — wrote a fascinating book a few years ago about the “acting white” phenomenon as an “ironic legacy of desegregation.” In it, he documents how black educational achievement at all-black schools was higher than at desegregated schools, even when black schoolchildren had to work in much reduced material conditions. The reason, he theorizes, has to do with a sense of strong community ownership of schools in black communities; it was usually black schools and black teachers who lost out in desegregation. And it has to do with black kids having to deal with the intense stress of competing with whites, particularly in the context of an overall culture marked by the ideology of white supremacy. His book certainly is not a defense of segregation, but it does show how socially and psychologically complicated this story is.

It can’t be denied that white flight from integrated schools made a big difference in the failure of desegregation. But here’s another complicating factor: when black families got into the middle class, many of them left those same schools and headed to the suburbs. They weren’t racist; they wanted to get their kids away from poor black kids from dysfunctional families. Under segregation, they had no choice but to go to those schools. Were they wrong to want out? You might make that argument, but what you can’t do is call their decision racist.

In some places, liberal whites congratulate themselves on still sending their kids to public schools, even though their kids are a minority there. But this can be deceiving. In one Dallas school I wrote about when I lived there, the children of whites actually attended a kind of school-within-the-school, taking advanced courses in which their classes were predominantly white. A Latino school administrator complained to me (as a journalist) that the white liberals were getting credit (among themselves) for their commitment to public education, but in truth their kids didn’t have to deal with the down side of integration: the fact that kids who came from poor and working-class families often had to deal with a lot of family dysfunction that kept them from achieving educationally.

This was (is) a matter of class, and this was (is) a matter of culture. Liberal white friends of mine who teach in heavily minority public schools do so out of idealism, but the stories they tell about the conditions in the schools — regarding the kids’ behavior — are horrifying. One of these friends decided that whatever it took, his children would not attend public school in his district. It wasn’t a matter of the school being public; it was about the kind of public that attended those schools. The violence, the sexualization within those kids’ cultures, the stigmatization of educational achievement — all of these were things that teacher had to deal with every day in the classroom. He didn’t want it for his children.

One white liberal friend of mine quit teaching in her inner-city high school in Baton Rouge when a teenage black male she was trying to discipline told her that if she didn’t leave him alone, he was going to be waiting for her in the parking lot, and was going to rape her. That was the last straw for her. She did not feel safe at the school, and did not trust the administration to protect her. She left teaching, and took up another line of work. More recently, I spoke with an older black woman who quit teaching in a different (mostly-black) public school system after decades, because she could no longer bear the disorder among the students, and the contempt that their parents showed for teachers, and for the educational process. Was she racist too?

I cannot imagine that a black, Latino, or any minority parent who could spare their children such an educational environment would not do so. But this does not show up in Hannah-Jones’s analysis. It’s all about racism.

To be clear: I don’t doubt for a second that pure racism motivated many white parents back then. But I also don’t doubt that for many more white parents, motives were much more mixed than Hannah-Jones indicates.

Simply as a political matter, though, it’s pretty incredible that progressives want to bring up busing again as a cause to fight about in the presidential race. They’re holding up an ideal — achieving de facto desegregation — as something pristine and unchallengeable, and blaming anyone who dissents from it as motivated by bigotry. Maybe 1970s-era Joe Biden was a hypocrite. But he represented the views of his constituents. As this recent story in the Washington Post pointed out, busing was hugely unpopular:

Polling from that time, and for many years to follow, shows that Biden was swimming in the mainstream. Surveys consistently showed majority support for the Brown decision against separate-but-equal education but widespread opposition to using busing to achieve racial integration.

A 1972 Harris Poll found that only 20 percent of Americans favored “busing schoolchildren to achieve racial balance,” with 73 percent against it. A 1978 Washington Post poll found that 25 percent agreed that “racial integration of the schools should be achieved even if it requires busing.”

African Americans were more supportive than whites but also had concerns. John C. Brittain, a civil rights attorney who litigated school segregation cases in that era, noted it was usually black schools that closed, black teachers who were fired and black children who were forced to travel.

“African Americans always had to bear the brunt of implementing school integration,” Brittain said.

In a 1973 Gallup poll, just 9 percent of black respondents chose busing as the best way to achieve school integration from a list of options. The most popular was creating more housing for low-income people in middle-income neighborhoods.

Still, when asked directly by Gallup in 1981 whether they favored busing to achieve racial balance in schools, 60 percent of black respondents said yes, compared with 17 percent of whites.

Still, 40 percent of blacks opposing busing less than a decade after its success in physically desegregating schools is pretty damning.

So, yes, I think it is loony of the left to want to pick a public fight over school busing, especially if it makes voters think that a Democratic president would favor policies that encourage it. For older generations of Americans, busing is a condensed symbol of an entire worldview that sees people who oppose this or that left-liberal policy proposal as deplorables in need of smashing for the sake of justice. It appears that for certain progressives, opposition to busing is a condensed symbol for white intransigence. Identity politics is all about condensed symbols.

It is important and justified to talk about the de facto segregation of American schooling, and how we might overcome that. Yet a core conservative insight is that not every problem is solvable, or at least the solutions to particular problems might impose too high a cost in other areas to be worth it. That’s one way to look at busing as a solution to the desegregation challenge. Telling the American people that achieving certain racial ratios in public schools is a goal so important that no other considerations can be weighed against it, and if they don’t want to accept that judgment, that just shows how racist they are — well, progressives, good luck with that. Your moral absolutism and quickness to embrace the validation that comes with indignation blinds you to your own self-interest. You are making it so much easier for Donald Trump. You don’t want to hear that, but there it is.

Advertisement

July 12, 2019

The Totalitarian ‘They’

Sohrab Ahmari of the NYPost tweeted this:

Every once in a while stories pop up that seem custom-made for The Post, as if by the hand of Providence.

— Sohrab Ahmari (@SohrabAhmari) July 12, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Yes indeed! My valve slammed shut when I read that.

Similarly, every once in a while a piece of journalism will appear that seems custom-made for this blog. In the case of New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo’s latest bit, in which he calls for the abolition of gendered language. Mind you, Manoo is not a columnist for the Oberlin student daily, but the most influential newspaper in the world. He says he’s a normal suburban dad, and doesn’t mind if you call him “he.” However:

But “he” is not what you should call me. If we lived in a just, rational, inclusive universe — one in which we were not all so irredeemably obsessed by the particulars of the parts dangling between our fellow humans’ legs, nor the ridiculous expectations signified by those parts about how we should act and speak and dress and feel — there would be no requirement for you to have to assume my gender just to refer to me in the common tongue.

Right. We’re the ones who are “irredeemably obsessed” with genitalia, not the progressives who can’t stop talking about it. More:

I think that’s too cautious; we should use “they” more freely, because language should not default to the gender binary. One truth I’ve come to understand too late in life is how thoroughly and insidiously our lives are shaped by gender norms. These expectations are felt most acutely and tragically by those who don’t conform to the standard gender binary — people who are transgender or nonbinary, most obviously.

But even for people who do mainly fit within the binary, the very idea that there is a binary is invisibly stifling. Every boy and girl feels this in small and large ways growing up; you unwittingly brush up against preferences that don’t fit within your gender expectations, and then you must learn to fight those expectations or strain to live within them.

Read it all. Michael Brendan Dougherty pushed back, which drew a Twitter response from Manjoo. to which MBD replied:

You can’t understand *anyone* who doesn’t question *everything?*

Maybe other people are both more humble about their reasoning ability, and more grateful that hundreds or thousands of years of human practical experience supplies answers where individual abstract reasoning fails. https://t.co/nqiwOi2f0F

— Michael Brendan Dougherty (@michaelbd) July 12, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Well, not only that, but Manjoo seems oblivious to the ideological privilege he has. Try questioning publicly “every inherited part of the culture and seek to justify it” when the inherited part of the office culture is the standard progressive roster of Thou Shalt Nots — including questioning the abandonment of the gender binary. I am writing this from Poland, which is in general a more culturally conservative country than the US. There are people who work for US-based multinationals who are afraid that they’re going to get fired if they object in any way to this stuff being introduced into their workplace via ukase from American HR departments.

Damon Linker has a great piece about how out-in-left-field-over-the-wall-into-the-bleachers-and-halfway-to-Albuquerque liberals have become on gender in just two shakes of RuPaul’s tail. Linker points out that Manjoo is not going out on any kind of limb here. This kind of gender radicalism is now part of everyday discourse in pop culture, advertising, media discourse, and in the catechisms generated by corporate HR departments. Here’s the most interesting part:

The first thing to be said about these convictions is that, apart from a miniscule number of transgender activists and postmodern theorists and scholars, no one would have affirmed any of them as recently as four years ago. There is almost no chance at all that the Farhad Manjoo of 2009 sat around pondering and lamenting the oppressiveness of his peers referring to “him” as “he.” That’s because (as far as I know) Manjoo is a man, with XY chromosomes, male reproductive organs, and typically male hormone levels, and a mere decade ago referring to such a person as “he” was considered to be merely descriptive of a rather mundane aspect of reality. His freedom was not infringed, or implicated, in any way by this convention. It wouldn’t have occurred to him to think or feel otherwise. Freedom was something else and about other things.

The emergence and spread of the contrary idea — that “gender is a ubiquitous prison of the mind” — can be traced to a precise point in time: the six months following the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision, which declared same-sex marriage a constitutional right. Almost immediately after that decision was handed down, progressive activists took up the cause of championing transgender rights as the next front in the culture war — and here we are, just four short years later, born free but everywhere in chains.

Linker goes on to say that there is no limiting principle in any of this. It’s all rebellion:

Will Manjoo’s call for liberation from the tyranny of the gender binary catch on in the way that the push for same-sex marriage did before it? I have no idea. What I do know is that, whatever happens, it’s likely to be followed by another undoubtedly very different crusade in the name of individual freedom, and then another, and another, as our society (and others like it) continues to work through the logic of its devotion to the principle of individualism.

The only thing that could halt the process is the rejection of that principle altogether.

A couple of months ago, when I was in Prague, I sat in a pizza joint interviewing three of the late Czech dissident Vaclav Benda’s adult sons. One of them said something that stuck with me. He was paraphrasing his father:

At the heart of all the totalitarian regimes is the idea of correcting the Creator and stealing your freedom so we can build the new world.

I went back last night to search my electronic copy of Benda’s essay collection The Long Night of the Watchman. I was looking to see if a phrase close to this turned up. I found this:

There are times when Christians do not realize that the idea of the forced establishment of paradise on earth and the emancipation of man with regard to any kind of higher authority comes from the same crucible as the idea of the improvement of sinners (or elimination of their occurrence) with the help of draconian laws, the idea of Christian dictatorship (totalitarianism): rebellion against the Creator stands at the root of all this, the same longing arbitrarily to correct imperfections in His work of creation.

An interesting point! I read on, though, and found this:

Totalitarianism devotes all its strength, all its technical know-how, towards a single goal: the unimpeded exercise of absolute power. It is capable of the most bizarre tactical somersaults imaginable, but it can never, under any circumstances, admit that anything is more important, more sacrosanct, than “the leading role of the party.”

Substitute “progressive towards diversity and inclusivity” for “the leading role of the party,” and you’ve got a pretty good general explanation for these weird manifestations like Manjoo’s column.

Benda said there can be no compromise with totalitarians:

One has either to submit oneself unconditionally to the violent and totalitarian power which sees a threat in every shadow and every free breath, or to confront it and to pit real strength against it (even if this is “mere” moral strength, for even that has shown many times in the history of Christian civilization how effective it can be). What is without any sense at all is to try to persuade the power that we mean well, and that we intend to limit its monopoly (its very essence!) only in its very own interest.

You do know that this stuff really is totalitarian, right? I bet Manjoo doesn’t. It’s totalitarian in part because it will tolerate no deviations. Take the time to read James Lindsay’s and Mike Nayna’s terrific piece analyzing Social Justice as a religion. They say that adherents to the cult aim to establish total power over society, to remake it in their ideal image. Excerpt:

That Social Justice defines the ideology motivating a moral tribe is instantaneously clear. Few communities of people organized around a shared moral vision aside from the most orthodox and fanatical religious sects and cults (whether religious or not) exhibit the traits of moral tribalism more overtly than Social Justice. That Social Justice represents a moral tribe is particularly evident in its tendency to police the moral behavior and thought within it and, where it can, reach outside of itself with what seems to be inexhaustible fervor and near-utter intolerance.

As dissident Benda observed when dealing with the Communist version of this fanatical mentality — which, you will notice, he said can happen also in a Christian context (Benda was a devout Catholic) — there is no peace to be made with these people. They cannot tolerate others, because their reason for being would cease to exist. To tolerate others is to co-exist with “Hate.”

Here, in another Benda passage, is another way that the Social Justice cult and its pomps and works is totalitarian. Remember, he’s writing in the 1980s, talking about Communism. But keep in mind how this applies to what we’re dealing with:

This decisive modus operandi of Czechoslovak totalitarianism is the atomization of society, the mutual isolation of individuals and the destruction of all bonds and facts which might overcome the isolation and manipulability of the individuals, which might enable them to relate to some sort of higher whole and meaning and thus determine their behavior in spheres beyond pure self-preservation and selfishness. I like to use the image of an “iron curtain” lowered not only between East and west, but also between the separate countries of the East (it is very noticeable that our contacts with the west increasingly take the form of an absolute idyll in comparison with the difficulties and adversity we encounter in establishing direct relationships with people from other Eastern countries), between separate social classes and groups, between separate communities, regions and enterprises. But iron curtains were and are lowered inside communities and enterprises too, and—when it comes down to it—even within families (we’ll leave aside curtains around individuals and in their inner selves, whose functioning would require a more subtle analysis). …

Hand in hand and in simple logical connection with the destruction of all social bonds is also the denial of any sort of truth which would be just somewhat impersonal and beyond current practical utility (not long ago I was shocked by young students’ simple unfamiliarity with orthodox Marxist terminology—even in their own schools they no longer try to pretend they are presenting some truths), the collapse and reduction of all values to nothing, the denial of any sort of order, morality and responsibility and eventually the particular perversion of freedom (that supreme gift of God), which is tolerated or even preferred only as mere license and arbitrariness.

As Linker avers, the Left is racing as far and as fast as it can to total atomization, and to unwittingly destroying any natural connections between individuals, and between individuals and objective reality. In Orwell’s 1984, the State sought to conquer Winston Smith’s mind by making him believe that all truth derived from what the Party said — and the Party decreed that all reality was in the mind. If the Party said that 2 + 2 = 5, then that was true. The Party, through its artificial language Newspeak, sought to change the way people talked so as to limit, even eliminate, the ability to think contrarian thoughts. In the end, it would not be enough for the Party to terrorize all opposition to Big Brother into silent submission; the Party’s ultimate goal was to make all souls love Big Brother.

Does this seem overwrought to you? After all, we’re just talking about a dopey column by a sweet, nerdy Millennial NYT columnist, right? See, though, this is exactly how this stuff gets institutionalized. As Linker points out, four years ago, what Manjoo claims in his piece is arbitrary and oppressive was so normal that nobody even thought about it. Now this kind of thing is quickly becoming orthodoxy within the Inner Party leading progressive circles.

Manjoo engages in a classic piece of left-liberal rhetoric here, saying he wishes that our world were one

… in which we were not all so irredeemably obsessed by the particulars of the parts dangling between our fellow humans’ legs

See what he does here? The people who object to his absolutely radical proposal to alter English as it has been spoken for centuries, so that it can fit a bizarre model of biology that only a relative tiny elite of progressives accepts — hey, they’re the ones who are “obsessed” by meaningless flesh in people’s crotches. Fifteen years ago, progressives taunted those who questioned the wisdom of smashing the traditional model of marriage as being “obsessed” with what other people did behind closed doors, etc. The idea is to stigmatize norms as being arbitrary, irrational, and even immoral, as a way to pave the way for the uncompromising introduction of new norms … which are presented as obviously true and good.

Again: this is totalitarian. There’s no limiting principle within this insane ideology. If it’s going to be stopped, it’s going to be stopped by force. One hopes only moral force, and the force of voters pushing back as hard against it as it is pushing against us. One hopes by fighting like mad in the courts to stop it.

This morning in Poland, I am going to give a lecture on the Benedict Option to a group of Polish college students who are on a summer school focusing on theology and politics. I’m going to talk about the Ben Op in a mode that I rarely do: as giving them the kind of deep grounding and formation they need — spiritually, morally, intellectually, and in terms of fellowship and discipleship — to fight these fights. As in the case of Dr. Benda and the Czech dissidents, the day may come when the Party holds all the levers of power. Resistance will have to continue through other means. Doing the Ben Op now, though, means that we will have been formed in the mental, moral, and spiritual habits of resistance.

Advertisement

Karen’s FUS Story

Last night in Krakow, I met an American friend for dinner. She’s a Catholic, and a theological conservative. I guess the Jeffrey Epstein news back home came up, I’m not sure, but we quickly got to talking about the abuse scandal in the Catholic Church. We discussed it for a while in the context of it being impossible to understand accurately through ideological lenses (e.g., the Bad Guys are the liberals, or the conservatives). I talked about how one of the most disillusioning things for me back in the early 2000s, when I was still Catholic, and writing about the scandal, was learning early on that my own “side” was equally as likely to have on it abusers, liars, and priests (and lay leaders) who were willing to do whatever it took to suppress knowledge of the scandal.

I told her about how, in early 2002, a priest tipped me off about Cardinal McCarrick’s abuse of seminarians. A day or two later, a prominent closeted gay Catholic conservative called my editor, saying he was representing Cardinal McCarrick personally, and asked my editor to kill the story. My editor refused, but in the end, I couldn’t write the piece, as nobody would go on the record. I discovered quickly that only one person was in a position to rat me out to McCarrick: the late Father Benedict Groeschel, who was a real hero to conservative Catholics back then. The priest who tipped me off told me that the only person he told about the story was his spiritual adviser, Father Groeschel. What the priest didn’t realize is that Groeschel ran for years a center that treated and released abusive priests. And he didn’t realize that men like Groeschel are almost always loyal to the System over truth and justice.

Later that year, I saw this work personally in a case when a Dallas Morning News journalist tried repeatedly to telephone Groeschel to get his side of a story involving the mishandling of an abuse case. Groeschel refused his repeated phone calls. The reporter called me out of the blue, wondering if I had an in with Groeschel, as I was a conservative Catholic like Groeschel. I did not. When the newspaper finally published the story, Groeschel went ballistic, and issued a press release lying about the reporter’s attempts to contact him. Of course Father Groeschel’s legions of supporters bought it hook, line, and sinker, because no good conservative Catholic friar would deceive people to cover up for clerical abusers, right?

Groeschel finally stepped down from his popular EWTN program after he gave an interview in which he said that minors abused by priests are sometimes the aggressors in these cases, and that first-time offenders shouldn’t necessarily go to jail, because they may not have meant to do it.

This morning I’ve read a gut-wrenching “open letter” to particular leaders (at least one of them now dead) at the Franciscan University of Steubenville, from “Karen,” a young woman who was sexually abused by a now-deceased priest there. In her letter, she details the entire process of her abuse at the hands of a priest there who led student ministry, and how specific figures at FUS protected him, and encouraged her to stay quiet about it. (Much of this story was told last year in a long piece in National Catholic Reporter.) She eventually reached a settlement with the university over the abuse, but refused to sign a confidentiality clause — which I suppose is why she feels at liberty to make these allegations in public now. Excerpts:

Fr. Christian Oravec, your failure disappointed me the most. Considering the extensive list above, this claim carries a lot of weight. You worked through the settlement with me. It was a long and painful process. Yet, months after completing this settlement, you and Fr. Mike Scanlan allowed a very public memorial and dedication of the Portiuncula to Fr. Sam, complete with a poster size glossy photo of him placed in the Portiuncula. I don’t know whose idea it was, and all the people involved, but you knew the truth and allowed it. A failure that pierced my heart.

Fr. Christian Oravec, you and your lawyer insisted on a confidentiality clause, and I refused. You and your lawyer insisted on so many things, and I refused them because they defied the charter from the USCCB on handling these matters. You said that, as a religious order, you were not bound by those rules. I still wonder how many women there are who are not free to speak up, because you bound them in your web of silence? The USCCB called for integrity and honesty. You claimed exemption. You failed all of the women that are bound in these clauses. If you truly want Integrity and Truth, unbind these women tell their stories and be free of the burden of silence you have placed on them.

Fr. Christian Oravec, you failed every victim after me. I fought to include a clause in my settlement where you would create a system of advocacy and care for victims. You signed a legal document agreeing to set this system up to help victims avoid the hell I went through in the process. You legally agreed to protect future victims and provide an advocate to help them through the process. Then you never set this up. It has been over 13 years, and victims are still being misled, manipulated, lied to, and treated as the enemy. You promised to help these women, but you failed them, and you failed me. You failed deeply.

Fr Christian Oravec, Fr. Nicholas Polichnowski, and Fr. Richard Davis: you were the minister provincials after my settlement. I don’t know exactly where the disconnect happened, but NONE of you made sure the legal requirement signed off on by Fr. Christian was followed through on. Actually, the settlement seems to have disappeared from Fr. Sam’s file. Maybe it was never placed in there – or maybe it was removed? I don’t know by who or when. But, the cover-up goes to the top.

FUS outed Fr. Sam as an abusive priest last fall, but a month prior to that, Fr. Richard Davis shocked us by the news that Fr. Sam’s file with the province was empty except for family contacts. Where are the documents from my case? Where is my settlement? What about his loss of faculties imposed by the diocese of Steubenville? Where is the information about his stay at the treatment center? And all the other women who came forward – where are they? Minister Provincials of the Sacred Heart Province, you have failed me with your complicity in this cover up. You have failed all the victims after me by not following through on the advocate system you agreed to.

In April 2019, , which found five priests, including Fr Sam Tiesi, who are believed by the university to have sexually abused at least one person. And yet, if “Karen,” author of the open letter, is telling the truth, then no one involved in the decades-long cover-up has been brought to account for it. Faithful Catholic mothers and fathers are sending their children to this university, which is renown for its orthodoxy, and into the hands of a leadership that has not yet come clean on what happened, and how it happened.

I don’t know how many of the men Karen names are still alive. Father Sam Tiesi is dead, as is Father Christian Oravec, who was the provincial of the particular Franciscan religious order that runs the university. Still, if Karen’s letter is credible, it describes a deep and extensive culture of corruption, one that has to be confronted and exorcised (I speak metaphorically). If things have changed there in the past few years, I hope the current leadership will address Karen’s allegations, in detail, to reassure the faithful. If they haven’t changed, I hope the current FUS leadership — especially its new president — will admit these failures frankly, and commit itself to real and verifiable change. That is the only way to rebuild any kind of credibility.

If Karen is not telling the truth, or exaggerating, that needs to come out too. What is no longer acceptable is silence. Here in Poland, a conservative Catholic man in his 20s told me that there are a number of conservative bishops who are still under the illusion that people believe what they say simply because they are bishops, and hold authority. Even in a country as devout as Poland, episcopal credibility among the younger generations is shot even among many churchgoing Catholics, at least according to what I’ve been told. These young people grew up on the Internet. They know what happened in America, and elsewhere — and they don’t think that their own country is immune.

This is not simply a case of liberal vs. conservative. It never was. Not long ago, I was in conversation with a Catholic friend about all this. She said that she had given up any hope, however thin, that Pope Francis would clean up the Church. She said, “I don’t think the bishops have any idea how furious the laity are at them.” Finally she threw up her hands and said, “Burn it all down, and let’s start again from the ruins.” What she meant was that she’s so sick and tired of the corruption that she would rather stand out in a field praying with Catholics who wanted Christ more than anything else, and who cherished truth, as opposed to institutionalists who are devoted to protecting each other’s power and position more than anything else.

The friend who said that to me is really conservative, and devout. I bet she never imagined in this or any lifetime that she would be saying things like this.

In Poland, as in every other country in the former Eastern Europe that I’ve visited in researching my book, I’ve heard older Catholics say that the sex abuse scandal is just starting to arrive here, but they are sure that this is a campaign against the Catholic Church, and that there’s nothing to it. Meanwhile, the younger Catholics I talk to say otherwise. They say that a long-overdue reckoning is finally at hand.

Advertisement

July 11, 2019

Oskar Schindler’s Factory

Earlier this week, I thought I would go out to visit Auschwitz today. The town of Oswiecim is about an hour and a half from Krakow, and there are lots of tour buses headed there. Yesterday, though, I was warned against it by a couple of people in Krakow. They said that I absolutely should go, but that I should be aware that nothing can prepare you for it — especially the massive scale of the death factory. Because I have to be prepared to lecture at a Benedictine abbey this weekend, my friends said that I would be taking a risk by going to Auschwitz. It could take me some time to recover. One of my friends said that she speaks from painful personal experience.

“Go next time you’re here,” she said. “And if you can, go with a loved one.”

Instead, I went today to visit Oskar Schindler’s factory in Krakow, which the city has turned into a museum memorializing the experience of Krakow under Nazi occupation (1939-1945). If you’ve seen Schindler’s List, you know that he was a minor Nazi industrialist who ended up saving the lives of about 1,200 Jews by employing them in his Krakow enamel factory. When the Nazis began liquidating the Krakow Jewish ghetto, Schindler devoted himself to protecting his Jewish workers. Schindler used his Nazi insider connections, and paid extensive bribes, to keep them alive. By the war’s end, Schindler had exhausted his fortune on his mission of mercy. He is the only Nazi Party member buried with honor on Mount Zion in Jerusalem.

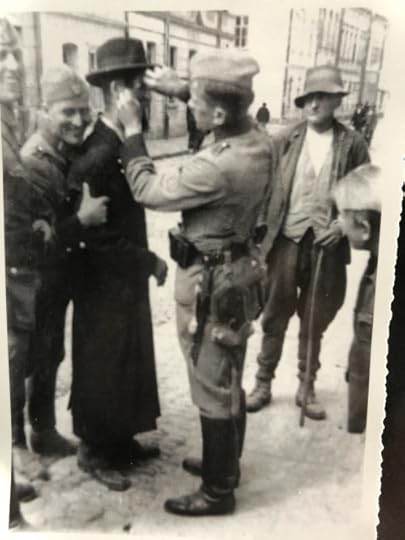

When they conquered Poland, the Nazis established their headquarters for the “General Government,” their term for German-occupied Poland, in Krakow. They turned on the city’s large Jewish population at once. Here is a photo from the museum showing German soldiers amusing themselves by shaving a Jew’s sidecurls and beard:

The governor was Hans Frank, Hitler’s personal lawyer and an occultist. He wrote in 1941:

A great Jewish migration will begin in any case. But what should we do with the Jews? Do you think they will be settled in Ostland, in villages? We were told in Berlin, ‘Why all this bother? We can do nothing with them either in Ostland or in the Reichskommissariat. So liquidate them yourselves.’ Gentlemen, I must ask you to rid yourself of all feelings of pity. We must annihilate the Jews wherever we find them and whenever it is possible.

In the museum, you turn a corner and see these … and it stops you cold:

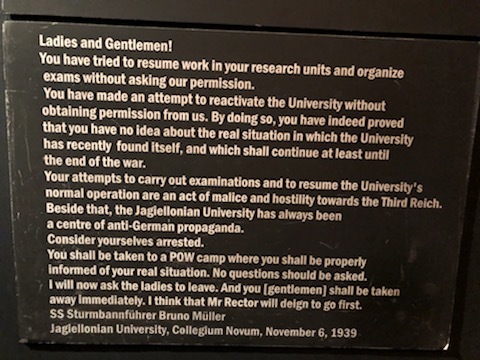

And there’s this on the wall, from one of Hans Frank’s deputies, in his statement announcing the closing the Jagiellonian University:

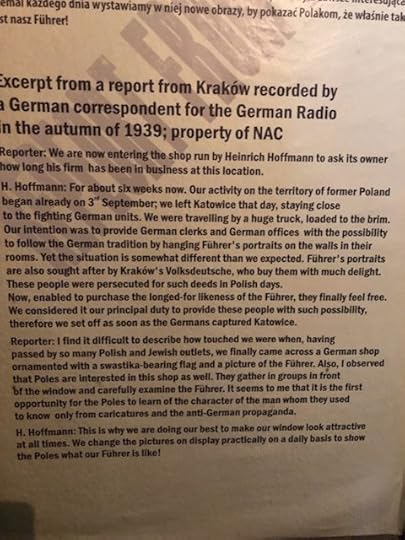

More — this from a German radio propaganda broadcast proclaiming the glories of life for ethnic Germans in Nazi-occupied Poland:

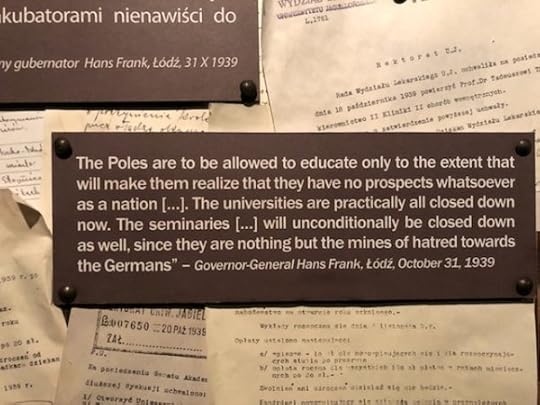

The Nazis wanted to eliminate all cultural memory of the Poles as a people, to grind them down into slaves:

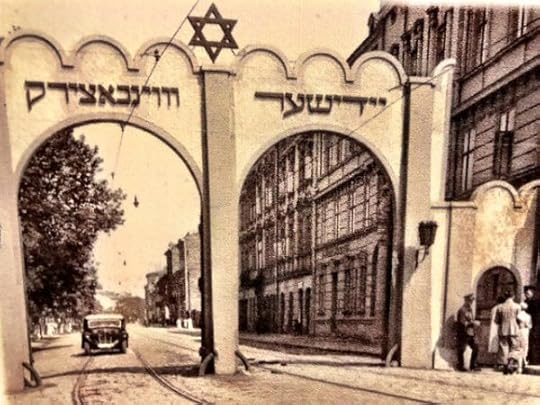

The Jews they simply wanted to murder … but not straightaway. Here’s what the entrance to the Krakow ghetto looked like:

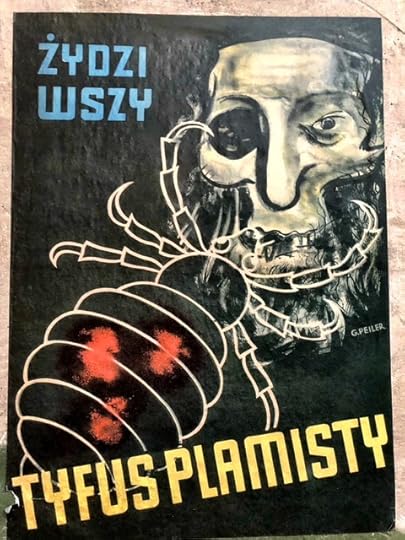

A Nazi propaganda poster proclaiming that Jews spread typhus:

It’s a kind of pun in Polish, saying that “there are lice called typhus”; “Zydzi wyzy tyfus” (without “plamisty”) means “there are all typhoid Jews.”

I didn’t have any great epiphanies in this museum. The effect was jarring, though: to come face to face with extreme evil — and this wasn’t remotely Auschwitz! I left the Schindler factory grateful that my friends had warned me about what confronting the great evil of the concentration camp would likely do to me. The reality of human evil is excruciating to face. Those are banal words, I know. But I tell you, having walked down the beautiful, charming streets of Krakow’s old town on my first day here, and then going to this museum and seeing film and photographs of Nazi soldiers parading in the same spaces — man, that shakes you up.

(A practical note for visitors to the Schindler factory: get your tickets in advance, online; they only let a certain number of visitors in at a given hour, to keep it from being too crowded.)

In the museum, I learned that “Schindler’s Jews” lived incredibly punishing, difficult lives, but they were the luckiest Jews of all — not just because they survived, but also because as hard as their lives were, they had it better than all other Jews living under Nazi terror.

I have long believed that the Holocaust was the most important event of the 20th century. It proves that no matter how culturally and technologically sophisticated we may be, we can revert to rank barbarism overnight. Solzhenitsyn warned readers of The Gulag Archipelago to be aware that what happened in Russia could happen anywhere on earth. It’s also true about what happened in Germany … and in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Let me end by saying that anybody who seriously compares what is happening anywhere in America today — however bad it may be — to what the Nazis did to Jews and others they hated should be ashamed. Just stop. Don’t go there. We have to keep the language for extreme evil like this pure, so what the Nazis did does not lose its power to shock the conscience.

Advertisement

View From Your Table

Krakow, Poland

At it again in Krakow — at a different Georgian restaurant from the other night. If you haven’t read this great New Yorker piece by Lauren Collins about Georgian cooking, run, don’t walk. It’s as unusual and as delicious as they say.

That’s not a very exciting photo, I admit, because I couldn’t position it right. Here’s a better one, taken from the viewpoint of my dining companion. Here is Self eating his first-ever Georgian pork soup dumpling (called “khinkali” in the plural):

In other culinary news from Krakow, I went today to Szambelan, a nifty little shop that sells flavored vodkas from jars. You taste what you like, then ask them to fill a bottle of the size you choose. They package it to travel:

I bought a little bottle of the plum and cherry vodka, on the bottom right. I liked the honey and black pepper vodka, but it struck me as a harder sell to the guests I’m bound to have sitting around the fire in the dead of winter.

Tomorrow I’m headed up to the thousand-year-old Benedictine abbey at Tyniec to give a couple of talks, and spend the weekend hanging out with monks and professors and students. I’m going to have to get in touch with that Georgian restaurant (Smaki Gruzji) to see if they can make a pillow-sized pork soup dumpling upon which I can lay my head, to guarantee sweet dreams.

Advertisement

Cardinal Newman’s Roses

“Because the bleeding was so heavy I didn’t know if the placenta was hanging by a thread, and that I had done more damage by going upstairs … I didn’t know if that scream would have ripped the last thread off the placenta and killed me instantly. I didn’t want to scream because I didn’t know if it would be my last scream.”

Instead, Melissa paused in the hope that her children might soon leave the kitchen to look for her, but the silence from downstairs left her nervous. In the midst of her desperation, Melissa said: “Please, Cardinal Newman, make the bleeding stop.”

“Just then, the bleeding stopped completely. It was just flowing very rapidly and then came to a sudden, complete stop,” she recalls.

Astonished, she climbed to her feet and said: “Thank you, Cardinal Newman, you made the bleeding stop.”

“Just then, the scent of roses just filled the air,” she recalled. “It was a powerful scent, it was so intense. It was more intense than if you went to a garden, or a store and smelled roses. I inhaled the smell of the roses and thought, ‘Wow!’

“It lasted for several seconds, it felt like a while, then it stopped and I said, ‘Cardinal Newman did you just make those roses for me?’ I knew he did and thought, ‘What a great gift.’ Then he made a second blast of roses up there. I thought, ‘Thank you Cardinal Newman.’

“Just then I realised I was OK and the baby was OK. I knew the baby was fine. I just couldn’t imagine that Cardinal Newman would stop the bleeding [and then after that] the baby wouldn’t make it. I knew in my heart that she was fine.”

Please read the whole thing. The Catholic Church investigated the case, and accepted it as a bona fide miracle. This was the second one officially accepted by the Church, and the one that made it possible for Pope Francis to canonize the 19th century English convert.

Here’s a tiny mystical experience that happened to me yesterday in Krakow. I left my hotel to go meet a contact. As you know, I’m here in Poland doing interviews for my next book. As I was walking down the street, I saw a woman on the other side of the street wearing a shirt with the slogan “Do little things with great love”. I recognized this as the core spiritual philosophy of St. Therese of Lisieux, the Little Flower. The epigraph for my book The Little Way of Ruthie Leming is based on this quote of Therese’s: “What matters in life are not great deeds, but great love.”

A second after I saw the woman, I was surrounded by the aroma of roses. It lasted only a couple of seconds, but it was definite — not something imagined. I laughed, and thanked the saint.

A few minutes later, I met my contact and we began talking. Though we had never seen each other before, we rather quickly got deeply into religious discussion, and the book I’m working on. The conversation was so unusually intense and significant that I felt at liberty to mention what had happened on the way to our meeting. She looked taken aback. She said, “Therese of Lisieux is my patron saint.”

I think we both had the sense at that point that there must be something spiritually significant about our meeting. More than that, I’m not going to say. We live in a world of wonders.

Advertisement

July 10, 2019

Fr. Jerzy Popieluszko’s Long Road

Hello from Krakow. I spent my last morning in Warsaw visiting the grave of the Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko, and the small museum next to it celebrating his life and death. The museum is connected to the Warsaw parish, St. Stanislaus Kostka, where Father Jerzy was serving at the time of his 1984 murder by the Communist secret police. He was 37 years old.

I was in high school when Father Jerzy’s assassination made international headlines. All I remembered about him was that he had been killed by the secret police because they considered him a threat to the regime, that he is revered as a martyr of Communism, and that his name sounded strange to the ears of English speakers (it’s pronounced “pop-eh-WOOSH-ko”).

As I would learn this morning, Father Jerzy – soon to be St. Jerzy Popieluszko, as the Catholic Church has documented proof of a miracle it attributes to his intercession – is one of the keys to this book I’m working on. Let me explain.

Father Jerzy is buried under a large stone cross laid on the lawn outside the parish. It is surrounded by boulders. It took me a couple of minutes to realize that they symbolize rosary beads, and that the cross stands for the rosary’s crucifix. The gravesite’s design emphasizes that Father Jerzy died in unity with Christ. Additionally, the layout of the rosary “beads” forms the shape of Poland.

In the museum’s lobby, my interpreter Lukasz and I waited for Pawel Keska, the manager for the development of the museum, and of documentation of the life of Father Jerzy. As we waited, I met a couple of American nuns from the Sisters Of Life, a pro-life order started by New York’s Cardinal John O’Connor. The sisters were accompanying a group of young American women from Focus, the Catholic college ministry, on a Polish pilgrimage. When Pawel arrived, he led us to a table in the museum cafeteria, and our interview began.

“I’ve been working here for two years. I’m a journalist and a theologian. And I have been thinking for two years why this person is important,” Pawel said. “And I see how important he is. Since Father Popieluszko’s death, his grave has been visited by 23 million people. Why? It’s still a mystery to me that I try to solve.”

(Note: in Polish, they use the term “Priest Popieluzsko,” which is how Pawel referred to him in conversation. In English, that sounds cold and harsh — which is not how it sounds to Polish ears. I have mostly rendered it “Father Jerzy” below, because that better conveys the spirit in which my interlocutor spoke about the priest.)

The first witness to the priest’s life that Pawel met told him a story that a million Poles turned out for the murdered cleric’s funeral there at St. Stanislaus Kostka parish. (Official estimates are 250,000, but many Poles say that’s an official number released by the Communist regime, which vastly underestimated the number for political reasons; the museum maintains that the number is between 250,000 and one million.) The Communist regime sent soldiers to Warsaw to ensure that the funeral wouldn’t turn into a revolutionary insurrection. Cardinal Jozef Glemp, the nation’s primate, said the funeral mass, and Solidarity trade union leader Lech Walesa was one of the eulogists.

“The witness told me in that massive crowd he saw a police car,” said Pawel. “People were slamming their hands down on the car, shouting, ‘We forgive! We forgive!’” In that is an answer for the situation that our world is in now.”

Pawel had a second story for me. In a big city like Warsaw, a big city of big crowds and big historical events, it’s easy to forget the potential significance of tiny places, far off the beaten track. Two weeks ago, he accompanied a group of young pilgrims to the small rural village in eastern Poland where Father Jerzy was born. The district is so poor that when the priest, who was born just after the Second World War, had to study by candlelight, because there was no electricity. Pawel’s group met Father Jerzy’s brother, who still lives there, and is now an elderly man reluctant to receive pilgrims.

“The village is very ordinary – there’s nothing spiritual there,” said Pawel. “In the home where Father Jerzy lived, there’s one room that has been set apart as a kind of museum, but all the items there are under a thick veil of dust. By the wall is a small table, covered with a kind of plastic sheet. There was a small piece of paper with handwriting on it, written by Father Jerzy’s brother. It said, Every day near the table we were praying with our mother. There was a photo of that mother as an old, tired woman. On the other side of that piece of paper was a reliquary with Father Jerzy’s relics.”

“And that’s the answer,” Pawel concluded, speaking of both stories. “The whole strength of that man, and what we need today for our identity.”

What he meant was that Father Jerzy became a figure of enormous historical significance for the Polish nation and the Catholic Church – and indeed will soon be canonized – but it all started there in a dull village in the middle of nowhere, with a faithful family that prayed every day together.

Pawel said that when he leads tour groups of students through the museum, in the room devoted to Father Jerzy’s youth, he emphasizes that the future saint and national hero was a hard-working student, but did not achieve high marks.

“When he was studying at seminary, he barely passed his exams. He was trying to learn a lot, but he simply wasn’t an intellectual,” said the researcher. “Students start to be interested in the man because he was like many of them. Intellect is not what it’s all about.”

“The answer to our problems in modernity is not in the intellect,” Pawel continued. “The answer is somewhere deeper, more profound. Father Jerzy’s strength was perfection in human relations. He loved life. He loved people. It was really hard during the Communist period to cultivate such simple values as honesty, and being kind with others. That was an exam he passed with flying colors. He was constantly challenged, but he constantly upheld his values, till the very end of his life.”

It has been 35 years since Father Jerzy’s murder, and two decades since Communism fell. Pawel sees a change in the mentality of the museum’s visitors – a widening chasm between the generations of Poles who come here.

Fewer and fewer people remember Communism. For those who do, it’s [the priest’s] martyrdom that’s the most important aspect of his story. It’s also a story of Polish nationalism. For them, there’s no distinction between Polish national identity and the Catholic faith. For younger people, though, it’s not so simple. We are trying to find a new way to tell the story of the priest Popieluszko to them. We are developing a narrative based on the most fundamental values, things like faith, identity, and responsibility. The young people who don’t remember Communism, they are coming for something else. They are looking for a guide in their life.”

European pilgrims who visit Father Jerzy’s grave and his museum live in a highly secular world. They are typically looking for a guide to teach them how to be faithful in a godless society. The Americans who come are often more devoted, but they’re also searching, Pawel said.

“Everybody comes for something different here, but the best thing is that they find it.”

On the fence separating Father Jerzy’s gravesite from the street hang banners from Solidarity chapters around Poland. Though he was not a member of the trade union, the priest’s life and death is inseparable from Solidarity’s own.

“Father Jerzy lived in a time when everything was politicized,” Pawel said. “The Church in Poland in that time didn’t declare publicly its involvement with Solidarity. It wanted to underline that they were separate things. Father Jerzy stood up in defense of the people of Solidarity, of which he was an honorary member. He was considered to be Solidarity’s chaplain.

The young priest faced harsh accusations about his political associations both from within the Communist regime and the Catholic Church. Once Cardinal Glemp questioned him critically about his labors in the public sphere. Though Father Jerzy never openly criticized the Church hierarchy, he confided to his diary that this experience was even more difficult to endure than his interrogation by the secret police.

The point is not that Father Jerzy was not political. He certainly was. But he did not set out to be political, and didn’t operate like a political person. Still, he had a political effect.

“When we look at the photos of his masses, and search the crowd, we see the faces of people who later became the most important politicians in Poland,” Pawel said. “But Father Jerzy never tried to create political networks.”

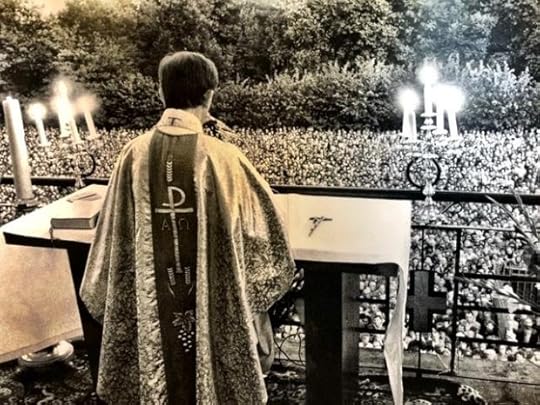

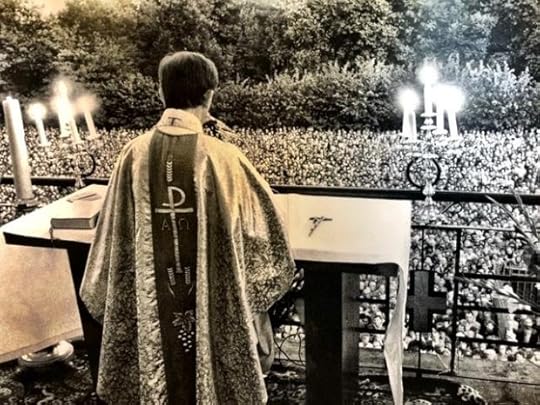

Fr. Jerzy officiates at a funeral mass held for a teenager who had been killed by the state police

Once when laborers at the Warsaw iron works went on strike, they invited Father Jerzy to say mass for them. Said Pawel: “He was a simple man, they were simple men, so they understand each other well.

“It wasn’t long after that that martial law was imposed, and a lot of the men who participated in that strike were sent to prison. Father Popieluszko supported them. He sent them packages in prison. He defended them in his sermons. He went to their court hearings, so he could look the judges right in the eye. These weren’t political activities; this was just human relations.”

The young priest quickly gained a reputation for being a man one could turn to for help. Perhaps more importantly, he inspired those he helped to respond to the crisis within Polish society by helping others. After the 1981 imposition of martial law, he began celebrating what came to be called “masses for the Fatherland” – that is, liturgies intended to ask God’s help for the suffering Polish nation. These outdoor masses drew crowds in the tens of thousands. His sermons

“A kind of community started to develop, of people who knew each other from these masses,” said Pawel. “During his sermons, Father Jerzy said very simple things about freedom, about solidarity as a value, the importance of human dignity — you know, really the most basic things. And that’s why he was murdered: because a movement that couldn’t be controlled by anyone was too dangerous for the communists. To be honest, the Church even regarded him as hard to control.”

Here is a fragment from a 1983 sermon he gave:

Our Fatherland and respect of human dignity must be the common objective for reconciliation. You must unite in reconciliation in the spirit of love, but also in the spirit of justice. As the Holy Father said five years ago, no love exists without justice. Love is greater than justice and at the same time finds reassurance in justice.

And for you, brothers, who carry in your hearts paid-for hatred, let it be a time of reflection that violence is not victorious, though it may triumph for a while. We have a proof of that standing underneath the Cross. There too was violence and hatred for truth. But the violence and hatred were defeated by the active love of Christ.

Pawel again emphasized that Father Jerzy was not brilliant, but he had simple faith, deep decency, and a gift for talking about the problems real people faced every day, in language they could understand.

“When he was a kid, every day before school he went to church. The closest church was four kilometers [about 2.5 miles] away from home. In winter, it was still dark, and he would strike one stone against another to drive away the wolves. If we think about that story when we look at photographs of him celebrating mass for tens of thousands of people, it is the same man: he’s simply brave, and he’s simply devoted to the most rudimentary values. He believed them, and practiced them to the very end.”

The country road Jerzy Popieluszko walked to mass as a boy, knocking stones to scare off wolves

As the priest rose in prominence and influence, the state began harassing him. He received anonymous death threats. A brick with explosive materials attached was thrown through his apartment window. The secret police bugged his flat, and stationed officers outside his building, around the clock, for two years. They sabotaged his car’s steering mechanism, hoping to cause him to die in an automobile crash. For a time he struggled to sleep amid a barrage of phone calls in the middle of the night, often carrying obscene messages.

The regime opened an official investigation, and interrogated Father Jerzy many times. The government-controlled media blasted him over his masses for the Fatherland. “During one of sermons, he said please pray for me, because for the thirtieth time, I’m going to be interrogated by the police,” said Pawel.

Eventually state prosecutors filed charges against him. Father Jerzy stood accused of harming the socialist nation through his religious work. Prosecutors said that he thus exceeded the freedom of conscience guaranteed under law. The priest refused this preposterous charge, and defended his faith.

Pawel said that today, if we protect the gifts of faith, “they have enormous energy. He received them at home. Today we have a big problem with that. Maybe that’s why people come here – they are looking for the kind of education they should have received from home, but didn’t.”

Father Jerzy was often weak and suffering from ill health. Near the end of his life, he was particularly exhausted. Cardinal Glemp asked him if he would like to go to Rome to study – this as a way of getting him to a place of rest and safety. Even though he believed that his murder was fast approaching, Father Jerzy declined the offer of exit.

“He was suffering terribly, but said that he simply could not abandon the people who trusted him,” said Pawel. “He was not loyal to abstract ideals. He was loyal to the people in his life. Pain is not a value, but fidelity itself sometimes causes pain.”

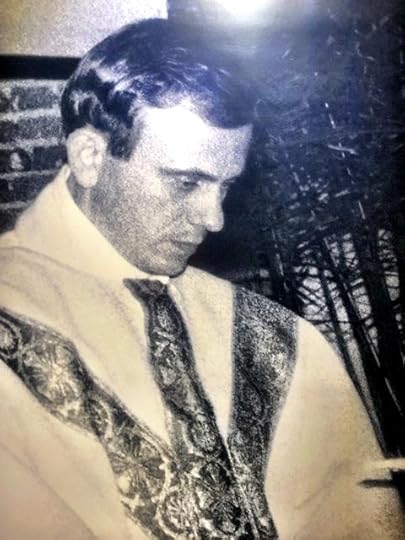

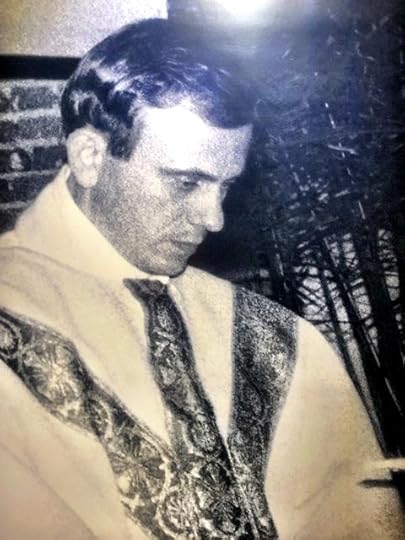

Here is the last known photograph of Father Jerzy Popieluszko:

Death came for him on the night of October 19, 1984. Three secret police agents kidnapped him, beat him severely, bound his hands and feet, tied a rock to his feet, and dumped him into a reservoir. His body was discovered on October 30. Here’s what he looked like:

See what they did to Father Jerzy

Eventually the trio was jailed for killing Father Jerzy, but later released as part of an amnesty.

Pawel told me that in his work at the museum, he’s looking for new language to pass the experience of Father Jerzy’s life to the post-communist generations. He finds that the different generations today speak “totally different languages in a totally different way.” A chasm is opening between Christians and the world, he said (“And within the churches too,” I added).

Under Communism, it was easier to talk because you knew where you stood, Pawel said. The oppression was so harsh that it helped Christians form strong identities. He went on:

In my work, I’m trying to find new language to pass that experience to the next generation. To start a dialogue, we have to have a common anthropological base. Today we have a really big problem with that, because we are speaking totally different languages in a totally different way. We have no common base. There’s a profound break between Christians and the world. The biggest problem is that under communism, such a dialogue was far simpler. The oppression was so obvious that it helped to form a strong identity.

But today? This is a much more difficult question.

Father Jerzy’s life offers us another way to see things, Pawel suggested. Consider that the priest knew that his entire society was infiltrated by the Communist Party.

“The priest who was his neighbor was a Communist informer,” Pawel said. “The priest who announced his death right here in the church was an informer. It’s quite easy to understand why Cardinal Glemp was so negative towards priest Popieluszko; the information he got about Father Jerzy came from priests who were secretly communist collaborators.”

All Poles had to live with this reality. In the face of it, Father Jerzy taught (in Pawel’s paraphrase): “You can’t worry about who’s an agent and who’s not an agent. If you do, you will tear yourself apart as a community.”

Said Pawel:

There was one man who came to to bring [Father Jerzy] a package. After that meeting, he stayed with Father Jerzy for three years, until his death. He was an atheist, but he started to be interested in church affairs, and he asked Father Jerzy something about the Bible. Father Jerzy told him to buy the Bible, but now, in this moment, to tell him how things are going in his family. When it comes to survival, maybe what’s most important is simple fidelity: not by evangelizing people directly, but by developing honest relations with one another – not looking for whether one is good or bad, or judging them by their ideology. Father Jerzy was constantly monitored by the secret police, who parked right in front of his home. During the severely cold winters, he would bring them hot tea to warm them up. Because they were people. That’s how he was.

I told Pawel that these stories — in particular, contrasting Father Jerzy’s lack of intellectual sophistication with his heroic goodness — teaches us something important. A lot of us Christians think that the way to convert others is to make better arguments. Good arguments are important, certainly, but when you see radical virtue made incarnate in a figure like Jerzy Popieluszko, it’s a more powerful witness to the truth of the faith.

Pawel began to talk about “realism.” Before he came to work at the museum, he was the spokesman for the Polish branch of Caritas, the international Catholic aid organization. He said:

In Poland, we had a really big ideological mess about migrants from the East. Working with Caritas, I met these people. And I was in Nepal doing work after the earthquake there, and in Ukraine doing war relief. I have also been in a lot of centers helping the homeless, and in the homes of single mothers and others.

Doing these things solidified my convictions. We can think different things about life and death, but what one needs to do is to visit a man just before his death, and talk to him. In my office, we were visiting homeless people, people in a really poor situation, to help them out. We had to know them. They’re people, not numbers.

Under Communism, people were forced to confront reality. Today, it’s far more difficult. We can think a lot, we can look up to important figures, but never live it out, never be slapped across the face by life. You cannot deceive a man who has fallen, because if he ever stands up, it’s because of real values — that is, values that survive the contact with reality. Let’s say that we teach people about good examples, but these example are merely theoretical — well, others will propose alternative examples, and the people will not be able to make up their minds.

Father Jerzy wasn’t a monk living isolated from the world. His biggest talent was that he was constantly with people. He didn’t isolate himself. He wrote in his diary, “I would like to go somewhere for a walk, but I have to stay here in the flat, because someone might come by for help.”

I would say that the test field when the truths we proclaim are verified is human dignity, where the discussion and theory ends, and real life starts. If we merely talk about dignity, and don’t live it, it’s simply a lie. It’s not true. These days, man now starts to become very theoretical. Our task is to convince people to establish real contacts with other people, to meet people face to face. Go to other people, like Father Jerzy Popieluszsko.

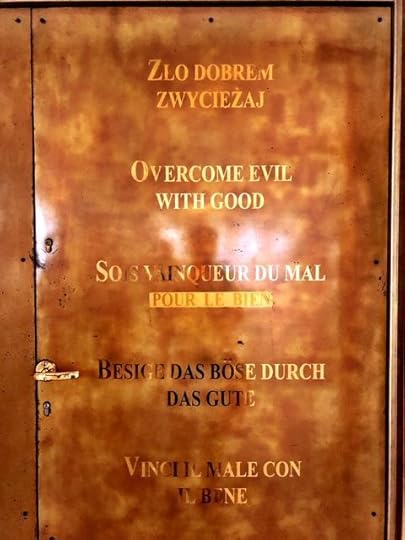

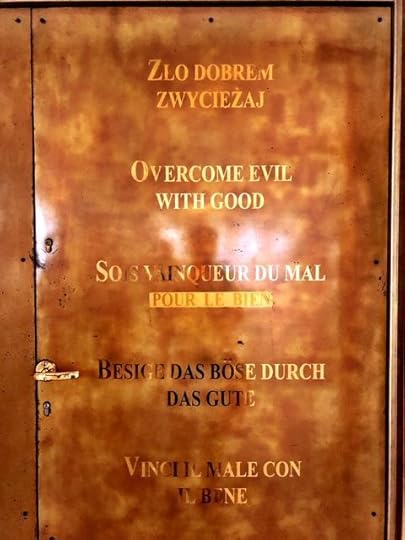

At the end of the museum tour, here is the exit door, featuring a command Father Jerzy gave to his followers, taken from a line of St. Paul’s:

“This is the part of the tour where I ask students what they think about what they’ve just seen,” said Pawel. “So, what do you think?”

I didn’t take notes of how I responded, of course. But this is what I said, or to be more precise, what I wish I had said:

Father Jerzy became a great leader of his nation, and is about to be canonized, because of the courage with which he loved. He was not a clever political strategist, but a simple priest whose understanding of what it meant to love God and his fellow man. What his life tells me is that we don’t have to have it all sorted out in terms of a political strategy in order to successfully confront the problems of our time. It is enough to speak and to live the truth in love, without fear.

There isn’t necessarily a clear-cut political program for us to follow. Father Jerzy had only the Gospel, and his formation as a Catholic, from childhood. This taught him what it meant to be human, and it taught him never to deny the image of God in every human person he met — even the secret policemen. You can build a politics on that. In fact, the only politics worth having is one that has defending human dignity at its center.

This doesn’t tell you, for example, if you should open your borders to migrants or not. But it does tell you that migrants are fellow human beings, and must be responded to with dignity and compassion.

Standing at the end of the story of his life, my thoughts went back to Father Jerzy’s childhood, and the image of that little Polish boy walking to mass through the morning darkness, knocking stones together to keep the wolves away. He went to mass because his mother and father, in their humble village home, taught him that Jesus Christ was everything. And they taught him that not just as an intellectual matter, but through regular prayer. In his path through life towards unity with Christ, Jerzy Popieluszko walked through the valley of the shadow of death, with only the steady rock of faith to keep the wolves at bay. Eventually the wolves found him, beat him to death, and delivered his battered corpse to the waters, tied to a rock.

And now, Jerzy Popieluszko is about to be raised to the altar as a saint. All over Poland, there are squares and other places bearing his name. Who are these men who killed him? Where are the Communist wolves who tormented Poland? Most are dead, and if they are remembered at all, it is with infamy. Upon the rock of his confession of faith, Father Jerzy built his life, found his courage — especially the courage to love those who persecuted him — and eventually, because of that confession, died at the hands of wicked men who despised him for his faith, and effectively stoned him.

There is a great mystery here.

I thought about how much I have struggled to convince people that my Benedict Option idea is not about running to the woods to hide, but about taking on spiritual disciplines and fellowship that give us the eyes to see clearly what Christ calls us to do in this present darkness, and the strength to bear witness to that calling in the public square, come what may. Father Jerzy is an extraordinary example of this. If he had not been formed as a Christian from childhood praying with his family around the table, and if his courage in faith had not been built into his heart by those long walks to mass in the face of his fear of wolves, would Jerzy Popieluszko have had the vision and the bravery to stand up to Communist tyranny — and to do so without losing his conviction that even his Communist tormentors weren’t wolves, deep down, but fellow human beings? And to inspire so many others to live the same way?

Put another way: if Jerzy Popieluszko had retreated into a purely private life as a Catholic, nobody would have faulted him. Life was hard under Communism. As Pawel pointed out, it was difficult to develop real virtue in a society that had been corrupted by a false and evil ideology. But Jerzy Popieluzsko didn’t do that. He became a martyr, and is now going to be a canonized saint. Here’s the thing: if it had not been for that early formation, and if it had not been for his spiritual discipline as a priest, he would not have been able to have accomplished any of that. He would have lived and died as an ordinary man — maybe a priest, but an ordinary one. There’s no shame in that. It’s how most of us will live and die. But there’s no glory either, in this life or the next.

Every country is full of politicians and others living out their convictions in the public square. But there aren’t many Jerzy Popieluzskos. If the Christian churches are going to produce saints and heroes like that in a society filled with corruption and confusion — more confusion, it must be said, than existed under Communism (“It was easier to see the evil back then,” an old Pole told me), then we will have to be far more intentional and countercultural in our habits of formation within our families, our churches, and our Christian institutions.

Later, at lunch, my friend and interpreter Lukasz, who is a practicing Catholic, marveled over what we had just heard. He was born in 1997, and had grown up with the story of Father Jerzy Popieluzsko as a stock narrative in his education. But Father Jerzy only really came alive to him that morning. Reflecting on how it was that until yesterday morning, Father Jerzy had been nothing more than a historical figure to him, rather than someone who can teach him how to live faithfully right here, right now.

“They only taught me about how he died,” said Lukasz. “They never taught me about how he lived.”

Advertisement

Fr. Jerzy Popieluzsko’s Long Road

Hello from Krakow. I spent my last morning in Warsaw visiting the grave of the Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko, and the small museum next to it celebrating his life and death. The museum is connected to the Warsaw parish, St. Stanislaus Kostka, where Father Jerzy was serving at the time of his 1984 murder by the Communist secret police. He was 37 years old.