Rod Dreher's Blog, page 215

August 20, 2019

The NYT’s Woke-ism Undermines Liberalism

The liberal columnist Damon Linker tears the NYT’s slavery-is-everything project to pieces. For those just now tuning in, the “1619 Project” is a massive effort by the Times to — in the words of an introduction by the NYT Magazine — “tell our story truthfully.” The newspaper means America’s story. In the view of the newspaper, slavery is the central event in American history. The founding of America did not simply entail slavery; it WAS slavery. Excerpt from Linker’s column:

Now, there is a lot to admire in the paper’s presentation of the 1619 Project — searing photographs, illuminating quotations from archival material, samples of poetry and fiction giving powerful voice to the black experience, and gripping journalistic summaries of scholarly histories. Much of it is wrenching, moving, and infuriating. The country’s treatment of the slaves and their descendants through the century following emancipation and, in some respects, on down to the present was and is appalling — and the story of how it happened, and keeps happening, is extremely important for understanding the United States. Bringing this story to a wide audience is a worthwhile public service.

But:

Yet that isn’t the point of the 1619 project. The point, once again, is to “reframe American history” so that this appalling history stands at the very center of who we are as a country. Achieving that goal has required the Times to treat history in a highly sensationalistic, reductionistic, and tendentious way, with the cumulative result resembling agitprop more than responsible journalism or scholarship. Putting aside any pretense toward nuance or complexity, the paper has surrendered to the sensibility of left-wing political activists. The result is unpersuasive — and a sad comment on the state of our country’s public life.

Throughout the issue of the NYTM, headlines make, with just slight variations, the same rhetorical move over and over again: “Here is something unpleasant, unjust, or even downright evil about life in the present-day United States. Bet you didn’t realize that slavery is ultimately to blame.” Lack of universal access to health care? High rates of sugar consumption? Callous treatment of incarcerated prisoners? White recording artists “stealing” black music? Harsh labor practices? That’s right — all of it, and far more, follows from slavery.

Linker goes into detail about how shallow and ideologically driven this project is. The silliest essay of the bunch, says Linker, is one by a Princeton historian who blames slavery for Atlanta’s traffic jams. The best essay, in Linker’s estimation, examines the capitalist foundations of slavery, but radically and ridiculously oversimplifies history to make the historical narrative fit 21st century political requirements. (When I read it, I thought, “Did this author never hear of the “dark Satanic Mills,” as Blake called them, of England’s Industrial Revolution?) In Linker’s estimation, that piece “turns historical scholarship into propaganda for a left-wing political movement.” More:

And the 1619 Project is all about advancing a radical political agenda. The message it aims to convey is clear: The United States is and always has been, from its very origin, a racist country infected by a white supremacist ideology that has birthed and nurtured institutions and systems — from Congress to capitalism — that systematically disadvantage black Americans. Political actors of the present have a simple choice: They can either embrace (invariably left-liberal or socialist) policies that will begin the process of dismantling these pervasive forms of structural injustice — or they can oppose doing so and ensure that the injustices continue, with toxic racism remaining where it has been for the past four centuries, at the very center of American life. Those are the choices.

You’re either part of the solution or part of the problem.

Linker points out that in the leaked transcript of the in-house town hall meeting chaired by executive editor Dean Baquet, the Times’s top newsroom leader did not question an unnamed questioner’s assertion that “racism is in everything,” and instead assured the questioner that next year, race was going to be central to the newspaper’s coverage.

What an astonishing capitulation of journalistic standards to political expedience! We now know without a shadow of a doubt that the most influential news organization in the nation, and probably even the world, is operating on an algorithm that forces the multifarious complexity of events in the life of this diverse nation to conform to left-liberal race dogmas.

Imagine what it’s like being a reporter or an editor at the Times, and disagreeing with this radical assessment of American history, and the approach the newspaper ought to take to reporting and analyzing the news. Would you have the courage to speak out? Of course you wouldn’t: they’d demonize you as a racist. You’re either part of the solution, or part of the problem.

If the black executive editor of the Times won’t even challenge the extreme assertion that “racism is in everything,” and ought to dictate how the newspaper does its job, why should you take that risk?

The Times just blew their credibility with anybody who doesn’t already agree with them. They’re not even trying to be objective. This is useful to learn, but I’m afraid it’s more serious than you readers who don’t give a fig about the Times and its ways understand. That newspaper, more than any other, both shapes and reflects the views of the American cultural elite. As I’ve written here often, the Times sets the agenda for other leading American media outlets, in part by framing what the media pays attention to. This extraordinary narrative — that the point of America from its very founding was slavery and racism — is now being injected into the mainstream.

This is totalitarian. In the book I’m working on now, I find that most of the factors that Hannah Arendt cited as pre-totalitarian — especially the radical isolation of individuals — exist in our present culture. But there are two important differences: surveillance technology is far, far more advanced than under communism or fascism, and has been far more integrated into daily life; and the anti-liberal ideologies of wokeness are taking over the leading institutions of American life (e.g., academia, media, corporate life). We are in a much more perilous situation than many people understand.

The UK academic Eric Kaufmann writes that wokeness really is totalitarian. Citing with approval Ryszard Legutko’s great little book about how much contemporary left-wing politics resembles what people suffered under communism, Kaufmann writes, of that parallel:

Arguments no longer revolved around truth, but were judged by their fidelity to the tenets of the secular religion. You were either with the movement or against it – those who tried to straddle the middle ground were denounced by socialists as ‘bourgeois’. The dishonest ‘slippery slope’ charge was repeatedly laid by communists to indict moderate opponents seeking some form of compromise between competing positions. Those on the opposite side of the debate were deemed ‘dangerous’ rather than incorrect.

History, the socialists believed, was moving inexorably in the direction of ‘progress’, and the role of the vanguard was to vanquish those standing in its way. Sound familiar? Anyone exposed to the power of the cultural Left in today’s liberal institutions, where ‘because it’s 2019’ is a killer argument, will recognise this.

You can see this in the Times‘s editorial decision to interpret all things according to the ideology of woke racialism. Insert “dialectical materialism” or “scientific socialism,” and you see what’s happening.

To be clear, Kaufmann criticizes Legutko’s book for judging liberal democracy too hard. Simply put, he says Legutko errs by saying that this kind of thing is inevitable in liberal democracy, when, on Kaufmann’s view, it’s rather a perversion of liberal democracy. But Kaufmann says the embrace by liberal institutions of wokeness helps destroy confidence in liberalism:

Legutko’s book can be read as a psychiatric report into the damage Left-modernism is doing to the cause of liberal democracy outside the West. Every time an athlete who appears to be a man wins a women’s sporting competition, Hollywood overdoses on wokeness at an awards ceremony, or an activist stages a hate-crime hoax, the prestige of liberal democracy suffers. New weapons are handed to opponents of liberty in authoritarian societies. Those who champion the rational form of liberalism based on equality of treatment and procedural liberty can now be accused of trying to transform the culture and ethos of their society.

All of which places a responsibility on sensible western liberals to push back the ideologues who would sacrifice centuries of hard-won liberties on the altar of utopia.

That’s what Damon Linker did in his column. Look what that’s getting him. This is typical. He doesn’t deny slavery was horrible and significant; he denies that it is the universal explanation for America. But hey, you’re either part of the solution, or part of the problem. It’s clear that problematic Damon Linker is an Enemy Of The People.

It’s one thing to say #1619Project isn’t good.

It’s another to say, as @DamonLinker says, that its “cumulative result” is like “agitprop more than responsible journalism or scholarship.”

This is what FASCISTS say about history they don’t like. https://t.co/ZmGpQ0MLzd

— John Stoehr’s Editorial Board (@johnastoehr) August 20, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Advertisement

In Defense Of Evangelical Cultural Pessimism

David French offers a challenge to Evangelical cultural pessimism. Excerpts:

One of the most striking aspects of modern Evangelical political thinking is its projection of inevitable decline, as if the present trends of secularization and increasing religious intolerance represent the first stages of an irreversible slide. The result is a fearful defensive crouch in the face of challenges to religious liberty that are serious but not grave and workplace discrimination that is troublesome but not crippling.

Another way to frame the challenge is that in parts of American society — especially in higher education and Silicon Valley — it’s not easy to be a traditional, orthodox Christian any longer. You’ll face threats to your liberty, to your career, and to your social standing. There’s a real (and often justified) concern that publicly stating the most basic tenets of your faith could result in suffering very real personal and professional costs.

Let’s put aside the question of support for Donald Trump for a moment. He’s not going to dominate American politics forever. He may not even dominate it two years from now. American Evangelicals — especially the conservative Evangelicals who feel most culturally embattled — face questions that will define their public posture potentially for generations.

French goes on to talk about how black Americans — and the black church — kept faith with America, and the American promise, even though for centuries they suffered under tyranny incomparably worse than that faced by white Evangelicals. If they had faith in America despite that, says French, what kind of excuse do white Evangelicals have for political despair? He goes on:

American Evangelicals approach our nation’s cultural conflicts from a position of far superior cultural, economic, political, and legal power than any marginalized community in American history. In that circumstance, to discard classical liberalism is to discard the very instruments and ideals that are most effective at guaranteeing your continued freedom and blocking the designs of those enemies who most fervently seek your demise.

But the fundamental lesson is even more profound. If men and women have the opportunity to speak and possess the courage to tell the truth, they have hope that they can transform a nation. What was true for black Americans (including the black American church) in the most dire of circumstances is still true for contemporary Christians in far less trying times.

Read the whole thing. French points out that as a lawyer, he has worked in the bluest of Blue America, and has found it uncomfortable and challenging, but nothing like what black Americans faced back in the day. If they didn’t despair (he says), why should we?

It’s an important point. When I get wallow in the slough of despond over these issues, I often think of Amos Pierce, the father of the actor Wendell Pierce. He is a World War II veteran. From his memoir, Wendell talks about the WW2 campaign to encourage black Americans to support the war effort (this, though half the country was living under apartheid):

Black newspapers around the country took up the cause and carried its banner throughout the war years. Of course the promise of the Double V Campaign was only half fulfilled. America won the war for democracy abroad, but refused to embrace it and prosecute it at home. Yet African Americans did not give up hope. They still believed in America, and wanted white Americans to believe in her too. The same faith in this nation’s promise would animate the civil rights movement. In 1957, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., would give a Christmas sermon in which he paid respect to the Double V Campaign, using the same rhetoric that would ultimately prevail in the war for the hearts and minds of America and its future:

Do to us what you will and we will still love you . . . . Throw us in jail and we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children, and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities at the midnight hour and drag us out on some wayside road and leave us half-dead as you beat us, and we will still love you. Send your propaganda agents around the country and make it appear that we are not fit, culturally and otherwise, for integration, but we’ll still love you. But be assured that we’ll wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom. We will not only win freedom for ourselves; we will appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.

In Dr. King’s soaring words, I can hear the testimony of my family. Burn our cars to teach us a lesson, nearly lynch our men for loving your women, piss on our children in church, steal our money and our right to vote, throw our broken bodies into an unmarked plantation grave, send us to a foreign land to fight and die for you, but deny us the medals we earned sacrificing for this nation—and we will not stop loving America. But we will win our freedom with a victory against the enemies—from within.

This was not sentimentality for my father. This was reality. I’ll never forget the lesson he taught me as a boy, the night he took me to a boxing match at the Municipal Auditorium. Daddy hates cigarette smoking, but he wanted to see the fights, so he sat miserably with my brother and me in the uppermost part of the bleachers, surrounded by a billowing cloud of smoke, waiting for the matches to begin. This was the late sixties or early seventies, when the Black Power movement was in full swing. That ethos demanded that when the national anthem was played, black people protested by refusing to stand in respect.

That night at the Municipal Auditorium, the national anthem began to sound over the PA system, signaling that the fights would soon begin. Everyone stood, except some brothers sitting in the next row down from us. They looked up at my father and said, “Aw, Pops, sit down.”

“Don’t touch me, man,” growled my dad.

“Sit down! Sit down!” they kept on.

“Don’t touch me,” he said. “I fought for that flag. You can sit down. I fought for you to have that right. But I fought for that flag too, and I’m going to stand.”

Then one of the brothers leveled his eyes at Daddy and said, “No, you need to sit down.” He started pulling on my father’s pants leg.

That was it. “You touch me one more time,” my father roared, “and I’m going to kick you in your fucking teeth.”

The radical wiseass turned around and minded his own business. That was a demonstration of black power that the brother hadn’t expected.

Like my father, my uncle L. H. Edwards fought for the American flag—his war was Vietnam—and came home to face discrimination as well. Uncle L.H. was a far angrier and a politically more extreme man than my father, but no matter how mad he was at what America had done to him and his people, his faith in America’s ideals and his loyalty to that flag did not waver. Like his son Louis says, “My father might have put on a dashiki, but he was going to wear it while he waved that flag.”

“You have to understand, my father was an officer,” Louis says. “He was so proud of that. He believed that there was no military in this world greater than the U.S. military, and you had better speak to him with respect because of it. He might have sung the black national anthem, but he wasn’t going to fly the flag of any African country, or any other nation but our own.”

The United States of America awarded Amos Pierce medals for his service in the Pacific theater … but a racist clerk handling his discharge denied him the medals. He never told his sons, in part because he didn’t want them to hate America. More from The Wind In The Reeds:

Those brave black soldiers, Amos Pierce and L.H. Edwards, taught me about true patriotism. This land was their land, too. It was made for them, same as everybody else. They never forgot it, and they weren’t going to let their fellow Americans forget it. Their patriotism said, “America is a great country, but we’re going to keep fighting to make it greater.”

In 2009, I did my small part in this long struggle to make our country a more perfect union when I contacted WWL-TV reporter Bill Capo in New Orleans and asked him to help me get Daddy his medals. I couldn’t let that injustice stand, not after all Amos Pierce had done for me and for his country. I explained what happened and Bill started looking into it. He contacted U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu, a fellow New Orleanian, who put her staff to work researching the issue.

What they found is that Corporal Pierce had not been awarded two medals, as he believed, but rather six of them. There was a Bronze Service Star, an Asiatic Pacific Campaign medal, a World War II Victory medal, a Presidential Unit Citation, a Meritorious Unit Commendation, and a Good Conduct medal, along with an honorable service lapel pin.

Working with the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, we arranged a special ceremony on Armed Forces Day, 2009, to present my father, then eighty-four, with his country’s thanks and honors. True, they were half a century late, but it’s never too late to do the right thing.

Major General Hunt Downer of the Louisiana National Guard spoke warmly of my father, telling the audience that we must never forget the debt of gratitude we owe to the Greatest Generation. Museum board president Gordon “Nick” Mueller added, “We would not have won World War II without the African Americans, the Native Americans, the Hispanics, the Japanese Americans.”

My brother Ron rose to speak, fighting back tears. He told the audience that our father “truly believed in the American dream, and he bought into it. And when he would tell us that we could do anything, he wasn’t just spouting words, he meant it.” (Ron said later that the event was surreal for him. “Here I was in the presence of a real-life American war hero, and it was my father—and I had no idea about it.”)

When my turn came to speak, I was as emotional as Ron was. My heart was bursting with love and pride in Daddy and all his comrades in arms. “It’s a great honor to stand here today,” I said. “But it’s not just for us. It is for all the men and women who couldn’t live to see this honor, and receive the honors they received, but still had love and faith for this great nation.”

Tee stood with us, at Daddy’s side. I hoped that my oldest brother, Stacey, who had died of heart disease a decade earlier, could in some way share that moment of triumph with our family.

Then it was time to give Daddy his medals. His face beaming, Daddy made his way with his walker to the stage. I stood at his side, holding the six medals in my hand, while Ron pinned them on the left breast of Daddy’s pin-striped suit. Tee looked on, cradling the box the medals came in.

Later on, his chest laden with colorful ribbons and bronze medals, Daddy told WWL-TV that he felt like General MacArthur. For us, it was enough that he was U.S. Army Corporal Amos Pierce, Jr., war hero. His family had always known it, but now the whole world did. America had finally lived up to the promises it made to a young black man who crossed the ocean and walked through fire and thunder for her. America had finally kept faith with an old black man who, despite everything, had taught his sons to believe in this great nation.

Whenever I hear people say, “So many people died for our freedom,” I say yes, you’re right—but I’m not thinking of battlefields alone. I’m also thinking of bayous and creeks and rivers where so many African Americans died, or endured the murders of their beloved husbands, sons, and fathers, at the hands of their fellow Americans who would never answer for their crimes in a court of law. And I’m thinking of the busy city streets and the lonesome country roads where so many black folk risked their lives—and in some cases, gave their lives—for the cause of liberty and justice for all Americans. There is blood on the ballot box, and it is the blood of black soldiers who fought for America—whether or not they ever wore the uniform.

They loved the country that persecuted them and treated them like the enemy. To me, that is a vision of supreme patriotism. It’s like my father always said to my brothers and me, every time we would see a triumph of American ideals: “See, that’s why I fought for that flag!”

Amos Pierce never stopped fighting for that flag, and never stopped loving it, either. On the day he finally received his medals, he said nothing at the formal ceremony, but at the gala afterward, he decided that he wanted to offer a few words to the crowd.

He hobbled over to the microphone and, despite his hearing loss, spoke with ringing clarity.

“I want you all to remember those who didn’t come back, I want to dedicate this night to them,” he said. “So many who fought didn’t even have a chance to live their lives. I was given that chance, as difficult as my life has been.”

Daddy thanked the audience for the honor, saying he was not bitter for having been denied the medals for so long. He was simply grateful to have them now.

“We’ve come so far as a country,” he continued. “I’ve realized now a lot of what we were fighting for.”

And then he paused. It took all of his strength to stand as erect as possible at the podium. He saluted crisply, and said, “God bless America.”

That’s when I lost it. For someone not to be debilitated by pain and anger and embarrassment after all he had been through; who fought for this country when this country didn’t love him and wouldn’t fight for him; to come back from war and still have to fight for the right to vote and the right to go into any establishment he wanted to—that made me think of the vow he made to me as a child: “No matter what, son, I will never abandon you.”

I have never known a greater man than that old soldier on the night he received his due.

Buy the book, read the whole thing. It’s an incredible story about a great American family. It’s also a story about America.

Now, with this knowledge, and with the moral courage of men like Amos Pierce there for us all to see, how do conservative white Christians (not just Evangelicals) justify pessimism?

Let me offer a counter-argument to French, even as I fully credit the point he’s making. Losing relative political and cultural power is not the same thing as oppression, and it’s important for white conservative Christians to do the hard work of discerning that difference.

David French is a lifelong Evangelical; he knows the Evangelical mind. I am not, nor ever have been an Evangelical, so I can’t speak for the Evangelical mindset. I can only say why I’m pessimistic about the future of Christians in this country in ways that might have been hard for black Americans of Amos Pierce’s generation to be about themselves. I’m going to say at the start that I’m not comparing the struggle (such as it is) of white conservative Christians today and in the years to come with what black Americans standing up to Jim Crow went through. I agree with French that it was far worse than anything we face now, or are likely to face in the next few years.

That said, I believe that conditions are meaningfully different, in a way that diminishes optimism. Here’s why.

The black Civil Rights generation were riding the crest of a massive social wave, carrying the country in their direction. Racial progress was not inevitable; nothing is inevitable, because history is not predetermined. But the tectonic dislocations in American life resulting from the war opened up space for black Americans and their demands for justice to be heard. Granted, this could be a misreading of the past from the perspective of the future. Did King and his cohort know in 1958 that they were going to overturn American apartheid within a few short years? Of course they didn’t. Still, given the overall movement of the culture at mid-century, and the confident liberalism of the dominant political culture, I think there was solid reason to be hopeful.

A big part of that hope was the reality that America was still a Christian country. That is, it was still a nation that paid respect to Christian values. The rhetoric of the Civil Rights movement is saturated with Biblical language, and not just because it was led by black preachers. That language made sense to Americans at mid-century, because most of us back then walked around with the Biblical narrative as our common culture. King (and others) challenged white American Christians — especially in the South — to live out their professed Christian faith. His famous letter from a Birmingham jail was written to the local white clergymen, chastising and challenging them to be faithful to the Gospel when it came to justice for black children of God.

We are a far less Christian country today, and if not post-Christian, then rapidly heading there. This, I think, is a distinction that makes a big difference re: French’s argument. You can’t cease to be black; you can cease to be Christian, or at least meaningfully Christian. We all know very well the statistics on how Millennials and Generation Z are leaving the faith.

One of the great frustrations I have with my own people (conservative Christians) is that we think political power is the most important thing to have. If we’re losing it — and we are — then we panic. Political power is important, no doubt about it, but over the course of my lifetime, I’ve seen the Religious Right wax and wane, and it has become clear to me that religious conservatives made a fundamental error in believing that political power was the most important thing to acquire (as distinct from an important thing to acquire). I’ve written about this many times, so I won’t go into it at length again here. The gist of my point is found in something I sent to a Christian professor friend yesterday. I told him that little makes me angrier than listening to middle-class conservative churchgoing Christians raise a fist to shake at the libs, while with the other hand giving their children smartphones, and participating uncritically in mass culture.

There is very little countercultural in conservative American Christianity as it is actually lived. If conservative Christians today despair over our marginalization, and coming persecution, then we might think self-critically about how we allowed ourselves to be assimilated into the culture that has now turned on us.

The point I’m getting at is that while conservative Christian leaders see the loss of political power as a prelude to a wider persecution — and, contra French, they are right to! — the far greater reason for concern is that our children are losing the faith. That is, we have failed to pass it on to them. Scripture says a man can gain the whole world, but if he loses his soul, he loses everything. Similarly, we conservative Christians can gain all the political power there is to gain, but if we fail to pass on the faith to the next generations, everything will turn to dust in our hands. That is happening now.

Come to think of it, the limits of political power can be observed in what’s happened to black Americans since the great Civil Rights victories of the 1960s. In 1965, eight percent of black births occurred outside of wedlock. Today, 72 percent do. The role broken families play in the intergenerational persistence of poverty is well-documented. To be sure, we now have a sizable black middle class, thanks to politics tearing down racist barriers to black economic advancement. And the collapse of the black family is not the only reason so many black Americans remain mired in poverty. (For example, globalism sending American manufacturing jobs overseas hurt all working-class Americans, but hit blacks hardest.) The point is that achieving political power may be necessary for achieving progress in material wealth and stability — for black Americans, it certainly was — but it is not sufficient.

I wonder what King and his team would have thought in 1958 if an angel had come down from heaven, told them all that they would achieve in terms of destroying the legal infrastructure of segregation, but also give them statistics on the black community’s struggles in 2019. I have no doubt that they would have pressed on with their cause, which was righteous. But don’t you think that they would have been taken aback by the failure of so many in the generations that followed to take advantage of what they won through their sacrifices?

Similarly, I think it is very important that American Christians vote for political leaders who will defend religious liberty — most importantly, the right to operate our schools and other institutions according to our own beliefs. But none of that will matter if we don’t use those liberties to educate and form our children in the faith. I swear, if Christians would spend even half the time, effort, and money concerning themselves with this rather than with politics, I’d be more optimistic about the future.

(Shorter Rod Dreher: “Y’all Christians stop despairing about the loss of political power; there are far more important reasons to despair!”)

But seriously, this is a thing. My intuition tells me that white Christian fear of losing political power is a manifestation of a deeper anxiety over the waning in our culture of the Christian faith itself — and that this is dread that many Christians can’t bear to recognize. I wonder too if David French has taken full measure of this fact.

We live in a culture that is post-Christian in the sense that the Biblical narrative is no longer central to the story we tell ourselves about us. In his research on the faith lives of young US Christians, sociologist Christian Smith found data that ought to terrify Christian leaders far more than the vagaries of Washington politics. I wrote about them here, in The Benedict Option:

As bleak as Christian Smith’s 2005 findings were, his follow-up research, a third installment of which was published in 2011, was even grimmer. Surveying the moral beliefs of 18-to-23-year-olds, Smith and his colleagues found that only 40 percent of young Christians sampled said that their personal moral beliefs were grounded in the Bible or some other religious sensibility. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the beliefs of even these faithful are biblically coherent. Many of these “Christians” are actually committed moral individualists who neither know nor practice a coherent Bible-based morality.

An astonishing 61 percent of the emerging adults had no moral problem at all with materialism and consumerism. An added 30 percent expressed some qualms but figured it was not worth worrying about. In this view, say Smith and his team, “all that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life.”

All that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life. This is the gospel taught by mainstream American culture. It is a very powerful message. If this is what people — even young people identifying as Christians — really believe, then on what basis can we realistically hope to turn this culture around? True, God can do anything, but remember: King and the Civil Rights leaders appealed to widely shared American values, values rooted in Biblical teaching. They appealed to a people that still believed that the Bible was authoritative, however poorly those people lived out the Bible’s teachings. That’s over now. All the deepest currents in our society — particularly the economic and technological ones — are carrying us farther away from a basis upon which conservative Christians could appeal to other Americans for respect and sympathy.

It is also undeniable that progressive culture sees traditional Christianity as little other than anti-gay and anti-abortion, both of which are profoundly offensive to beliefs cherished by progressives. In the 1960s, during the height of the Civil Rights struggle, the commanding heights of American culture were held by people who rejected Southern segregation. True, many were reluctant to take them on, but King and his team forced them to see that peaceful coexistence was no longer tenable. It seems to me that those who hold the commanding heights of American culture regard conservative Christians with similar contempt — and it is the generation rising to power who are compelling them to act on those beliefs.

Let me end with this. I posit the Benedict Option as the only realistic hope for traditional Christians to endure the darkness to come. People who haven’t read the book often assume that I’m talking about enduring a future persecution. That is part of it, but only a small part. By far the greater part of it is not about enduring persecution, but rather enduring the slow-motion collapse of the faith, along the lines of what happened to traditional Roman paganism in the 4th and 5th centuries. To be clear, St. Benedict and his monastic order arose out of the collapse of the Roman state and infrastructure of civilization (economic, technological, etc.); they held things together through a time of serious chaos and deprivation, and moved within a culture that was either lightly Christian or, as in the rural areas where they planted their monasteries, pre-Christian. They witnessed to a culture that had yet to become Christian, or where at best Christianity was a rising new religion.

Today, in the 21st century, we in the West have lived through the historical experience of Christianity. Though I am a Christian believer, as a cultural diagnosis, I affirm that Nietzsche was right: God is dead to the West; we are now living through the implications of that reality. The kind of witness that Christians offer takes place within that historical context. This is why the Benedict Option can only have limited correspondence with the actual, historical early Benedictines. Whatever survival strategies we Christians today adopt will have to be worked out within this cultural reality. And, crucially, they will have to be worked out in the face of an overwhelmingly powerful culture of disintegration.

Liberalism is an artifact of an Enlightenment culture whose fundamental bases are directly challenged by this culture of disintegration. That Enlightenment culture was, at its moral core, a secularization of Christian teachings. We are now engaged in a drama to see if liberalism — the most durable political expression of the Enlightenment — can survive the severing of its religious roots.

So, whether the pessimistic white Evangelical leaders know it or not, they are fighting a very different kind of war than the black Civil Rights leaders fought. The Civil Rights leaders fought on a battlefield whose borders were defined by that Enlightenment culture and what remained of its Christian framework. They had every reason to be optimistic. Traditional Christians today, in our post-Christian society, do not. I genuinely respect David French, who has fought hard in courtrooms for religious liberty. I don’t understand his optimism, though. The Civil Rights leaders fought for human rights; today, in our decadent culture, we can’t even agree on what the human person is.

Notice I say “optimism,” not “hope” — for Christians, hope is not the same as optimism. The martyrs were hopeful. Ignatius of Antioch, in his 2nd century letters written on his way to Rome for martyrdom, was hopeful, not optimistic. I am hopeful, but I am not optimistic. Because I am hopeful but not optimistic, I believe that even as Christians fight in the political arena to protect our liberties, we should also prepare for a long period of suffering. The chief form of suffering is not going to come from the state, or other persecutors, but from the dissolution of the faith via internal demoralization and loss of a sense of purpose. That is not something from which the black church of the Civil Rights era suffered, nor is it something that the early Church in the pre-Christian Roman empire suffered. But we have it today, and to the extent that Christian leaders are preoccupied with political power and status, they are failing to address the greatest challenge to the future of the faith in the West.

And: to the extent that any of us Christians believe that more of what we’ve been doing is the answer to this challenge (e.g., more programs, more therapeutic sermons, more entertaining worship, etc.), we are dramatically failing to understand the crisis. A young person, black or white, could look to the Civil Rights movement leadership in the 1960s and see men who, despite their flaws, were willing to suffer and die for their cause. Can you think of any Christian leaders today who would be willing to do that? Can you think of any Christian followers who would? Insofar as we regard our faith as the comfortable middle class at prayer, we are a bigger danger to ourselves than secular liberals are.

I’ll leave you with this: if you want to read more about why I think French’s optimism is unwarranted, read Michael Hanby’s terrific 2014 piece about the loss of the basis for civic Christianity. Excerpts:

What availed as the common wisdom of mankind until the day before yesterday—for example, that man, woman, mother, and father name natural realities as well as social roles, that children issue naturally from their union, that the marital union of man and woman is the foundation of human society and provides the optimal home for the flourishing of children—all this is now regarded by many as obsolete and even hopelessly bigoted, as court after court, demonstrating that this revolution has profoundly transformed even the meaning of reason itself, has declared that this bygone wisdom now fails even to pass the minimum legal threshold of rational cogency.

More:

Perhaps this kairos is a chance for some sort of synthesis rather than a showdown, for an opportunity to rediscover those dimensions of Christian existence that comfortable Christianity has caused us to neglect, and an opportunity not simply to confront but also to serve our country in a new and deeper way.

This synthesis cannot be a political one, as if the civic project of American Christianity could be revived by rejiggered coalitions or a new united front. We must rather conceive of it principally as a form of witness. Here some elements of the Benedict Option become essential: educating our children, rebuilding our parishes, and patiently building little bulwarks of truly humanist culture within our decaying civilization. This decay is internal as well as external, for while the civic project has been a spectacular failure at Christianizing liberalism, it has been wildly successful at liberalizing Christianity.

A witness is, first, one who sees. And none of these efforts are likely to come to much unless we are able to see outside the ontology of liberalism to the truth of things, to enter more deeply into the meaning of our creaturehood. Only then can we rediscover, as a matter of reason, the truth of the human being, the truth of freedom, and the truth of truth itself. It is no accident that Benedict XVI placed the spirit of monasticism at the foundation of any authentically human culture. For nothing less than an all-consuming quest for God, one that lays claim to heart, soul, and mind, will suffice to save Christianity from this decaying civilization—or this civilization from itself.

Martin Luther King and his people fought and defeated dragons. The identify of the enemy was clear back then, the swords they used to fight him were sure, and they had powerful allies. We Christians today don’t even understand the nature of the enemy, and the struggle upon us. That’s the difference.

Advertisement

Europe’s Open Southern Borders

Everything Christopher Caldwell writes is a must-read, I find. Here’s a piece about the massive demographic challenge facing Europe this century, and about how elites there don’t want to face it. Excerpts:

The population pressures emanating from the Middle East in recent decades, already sufficient to drive the European political system into convulsions, are going to pale beside those from sub-Saharan Africa in decades to come. Salvini owes his rise — and his party’s mighty victory in May’s elections to the European Union parliament — to his willingness to address African migration as a crisis. Even mentioning it makes him almost alone among European politicians. Those who are not scared to face the problem are scared to avow their conclusions.

Last year Stephen Smith, an American-born longtime Africa correspondent for the Paris dailies Le Monde and Libération, now a professor of African and African-American studies at Duke, published (in French) La ruée vers l’Europe, a short, sober, open-minded book about the coming mass migration out of Africa. The most important book written until then on the subject, it quickly became the talk of Paris. It has now been published in English.

Smith begins by laying out some facts. Africa is adding people at a rate never before seen on any continent. The population of sub-Saharan Africa alone, now about a billion people, will more than double to 2.2 billion people by mid-century, while that of Western Europe will fall to a doddering half billion or so. We should note that the figures Smith uses are not something he dreamed up while out on a walk — they are the official United Nations estimates, which in recent years have frequently underestimated population shifts.

The closer you look, the more disorienting is the change. In 1950 the Saharan country of Niger, with 2.6 million people, was smaller than Brooklyn. In 2050, with 68.5 million people, it will be the size of France. By that time, nearby Nigeria, with 411 million people, will be considerably larger than the United States. In 1960, Nigeria’s capital, Lagos, had only 350,000 people. It was smaller than Newark. But Lagos is now 60 times as large as it was then, with a population of 21 million, and it is projected to double again in size in the next generation, making it the largest city in the world, with a population roughly the same as Spain’s.

Caldwell writes that Smith’s book explores the tragedy of European investment to build up African industries, to deter Africans from wanting to migrate. It turns out that getting a little bit of money in their pockets actually works as an incentive to Africans to migrate. More:

The most serious heresy in Smith’s book is this: The extraordinarily disruptive mass movement of labor and humanity from Africa to Europe, should it come, will bring Europe no meaningful benefits. Narratives of Europe’s enrichment by migration are post facto rationalizations for something that Europe is undergoing, not choosing. Europe does not need an influx of youthful African labor, Smith writes, because both robotization and rising retirement ages are shrinking the demand for it. Migrant laborers cannot fund the European welfare state. In fact, they will undermine it, because the cost of schools, health, and other government services that philoprogenitive newcomers draw on exceeds their tax payments. Nor will the mass exodus help Africa. It will sap the rising middle class in precisely the countries — Senegal, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Kenya — with the best chances for economic success.

Caldwell goes on to talk about how Smith, who lived in Africa for many years, and worked as a correspondent for Paris’s left-wing daily, has been calumniated by French elites as some sort of rightist who doesn’t have the right to offer an opinion. Says Caldwell: “European political issues, like American ones, are increasingly matters of “values” and “rights” — whatever you call them, they are not up for negotiation.Read it all.

This week, Italy’s Matteo Salvini declared victory after a migrant boat he refused to let dock in his country received a Spanish offer of haven. He said, “Italy is not the refugee camp of Europe.” A Pyrrhic victory: other European countries have offered to resettle the refugees. They will have managed to get to Europe after all.

And remember, the migration from the South has barely begun. We’re not supposed to mention the name of Jean Raspail, who wrote the dystopic anti-migrant novel The Camp of the Saints, but I can’t think of a better summary of the tragedy facing Europe this century. I can’t find the precise quote, but it was something like this: “Either we accept this invasion, and we cease to be who we are. Or we take the necessary measures to stop it, and cease to be who we are. There are no other options.” By that latter point, he means that to undertake a successful defense of Europe from the tsunami of migration from the south would require mass killing, such that the Europeans would betray their humanitarianism.

From a 2013 interview with Raspail, in a French magazine (translation is mine, via Google):

How can Europe face these migrations?

There are only two solutions. Either we try to live with it and France – its culture, its civilization – will disappear even without a funeral. This is, in my opinion, what will happen. Or we don’t make room for them at all – that is to say, one stops regarding the Other as sacred, and we rediscover that your neighbor is primarily the one living next to you. This assumes that you stop caring so much about these “crazy Christian ideas”, as Chesterton said, about this erroneous sense of human rights, and that we take the measures of collective expulsion, and without appeal, to avoid the dissolution of the country in a general miscegenation [métissage, a word that in French carries more the sense of the English words “multiculturalism” and “diversity”]. I see no other solution. I have traveled in my youth. All peoples are exciting but when mixed enough is much more animosity that grows that sympathy. Miscegenation is never peaceful, it is a dangerous utopia. See South Africa!

At the point where we are, the steps we should take are necessarily very coercive. I do not believe and I do not see anyone who has the courage to take them. There should be balance in his soul, but is it ready? That said, I do not believe for a moment that immigration advocates are more charitable than me: there probably is not one who intends to receive at home one of those unfortunates. … All this is an emotional sham, an irresponsible maelstrom which will swallow us.

Raspail’s vision is extremely dark. But nobody has yet demonstrated to my satisfaction why he does not see the world of the near future as it really is, not as the rest of us prefer it to be. The fact that the choice he forces us to see is horrible doesn’t make it go away. Europe can’t avoid the choice. To refuse it is to choose. The coming migrants aren’t interested in the moral dilemmas of Europeans.

Advertisement

August 19, 2019

‘Discredited Entitities’

From Global Times, the Chinese government’s English language daily, this story under the headline “China punishes 12.77 million discredited entities as of 2018”:

The big picture in the construction of China’s social credit system via a blacklist has taken initial shape, and losing credit in one place might mean an entity is restricted in other places.

Coordinated efforts among different departments have led to strengthened punishments and yielded positive results, according to an annual analysis on the blacklist for discredited behavior, which was released by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s top economic planner, on Thursday.

As of the end of 2018, there were 12.77 million entities subject to credit penalties as disclosed by courts nationwide, while China restricted persons with bad social credit scores from taking more than 17.46 million flight trips and some 5.47 million high-speed train trips, the NDRC report showed.

Last year, more than 2 million entities exited the blacklist, including 1,417 taxpayers, after paying duties and fines, said the report.

Here’s how Global Times touted the story on Twitter:

China restricted 2.56 million discredited entities from purchasing plane tickets, and 90,000 entities from buying high-speed rail tickets in July: NDRC #socialcredit pic.twitter.com/4zAwJ7hrBn

— Global Times (@globaltimesnews) August 16, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

“Discredited entities” is the chilling Beijing euphemism for people who have low social credit scores. You can become a discredited entity for doing things like not paying fines. According to Wired magazine, the intrusiveness of the social credit system has been exaggerated in the West.

That may be. But watch what Beijing is doing to the Uighurs. This is not only about restricting lawbreakers. It’s about preventing people from dissenting from the government line, including doing things like going to church. As Joe Carter pointed out, in the 2014 document announcing the beginning of the system’s development, the Communist government said that when it is complete, it will “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.”

There’s a practical reason for this. Communism — especially the Cultural Revolution — destroyed civil society. Chinese people need to know who among them is trustworthy. Still, the problems here are obvious. Here’s a link to an episode of HBO’s VICE News explaining the system.

Here's a dystopian vision of the future: A real announcement I recorded on the Beijing-Shanghai bullet train. (I've subtitled it so you can watch in silence.) pic.twitter.com/ZoRWtdcSMy

— James O'Malley (@Psythor) October 29, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Keep in mind that the technology to implement this in the United States exists. The political will clearly does not. Let’s fight to make sure it never does. Companies already have the data to know a hell of a lot about us.

UPDATE: Here’s an article in The Nation explaining the social credit system, including why it’s popular. Excerpts:

We were near the entrance of the No. 1 People’s Hospital of Hangzhou in Zhejiang province, southwest of Shanghai. An old woman who seemed to be waiting for a taxi suddenly climbed over the roadside barrier, leaned over the hood of a German car, jumped up, then sat down on the ground, arms crossed. The frantic young driver got out and went up to her. They argued for an hour in front of nurses and a passing policeman until they agreed on damages.

Chinese online video platforms show many incidents of peng ci (touching porcelain), where people fling themselves onto cars to claim damages. They can be funny; more often, they’re dramatic. These extortions—plus scams in health, food, and counterfeit goods—make people angry and help explain why they are prepared to accept any government measures that claim to end them.

The most important measure is the new “social credit” surveillance system.

More:

Since anyone caught littering risks losing three points, there are no cigarette butts or empty cans on the city streets or buses. Because of the numerous high-end cameras made by Hik Vision—a world leader in video surveillance, whose major shareholder is the Chinese government—the police do not have to monitor in person. Crossing a road in Rongcheng city is no longer a challenge: Drivers stop for pedestrians, a rare occurrence in China. If they fail, the penalty is harsh: a 50 yuan fine ($7.35), three points off the driving license (which has an initial total of 12), and five lost social-credit points. “It happened overnight, in the spring of 2017,” said a passer-by. “The cars suddenly stopped in front of us. I didn’t know what to do.”

Sounds pretty good, right? But:

Many neighborhoods have adopted a residents’ code of good conduct. In the Qingshan district, large hoardings stress the priorities: pornographic, or “yellow,” books and films are banned, along with growing vegetables in the streets, going to non-registered churches, being rude to neighbors, and showing off in fancy cars at weddings and funerals. Breaking those rules can lead to a loss of points.

Advertisement

‘Giant Empty Houses’

I’m not sure what to make of this letter from a Catholic reader, but it adds meaningful detail to the stories we’ve been getting about a culture of sexual abuse and corruption in the seminary of the Catholic Diocese of Buffalo, NY. The pieces of mine he refers to are, in chronological order, here, here, and here. All the ellipses below are in the original:

Your coverage of the Buffalo diocese has been…..surreal. My wife is from Buffalo, her entire family still lives there, my oldest son was born there, and for the year and half I lived there I visited the seminary library a few times a month. Almost every person you’ve mentioned in the articles I’ve met and know. I sang in the choir at that Latin Mass parish in Cheektowaga that Fr. Nowak was at. I met Bishop Malone and was originally under the impression he was great.

But hopefully you and your readers are asking….why does Buffalo have a seminary? What other diocese has its own seminary?

I wanted to give you an idea of the seminary, in case people are picturing a college campus in the middle of downtown Buffalo. It’s in the middle of nowhere. You go down Transit Rd for about 15 minutes if you’re starting in Depew, then you turn left when you go under a bridge and see a diner on your left, and then you drive further and further and further into the woods, you see a Fisher Price sign (which is located in East Aurora) and when you’d left civilization you’re there.

It can house 250 priests, and was obviously built back when a diocese like Buffalo had 250 vocations any given year. Now it’s less than 20 (which is actually an uptick I think). So imagine being a seminarian in rural upstate New York, on about 200 acres of land, with maybe 12-18 other people (some of whom are significantly older than you if you’re a young man). It’s quite different from going to a seminary where multiple diocese send their guys. You’re basically a monk in Buffalo. And the truly crazy part is some of the parishes in Buffalo have residences that can accommodate 20 priests, but have only 1. So instead of giving these guys communities to support each other, they’re all living in giant empty houses.

I’d go to the library in the evenings after work if my wife was meeting her family for something. It was eerie. You pull in to a poorly lit parking lot with a statue of St. John Vianney (the only welcoming thing you see). You wouldn’t know people lived there. It was always so quiet. I’d walk into a pitch black library and turn on a few lights, and even though the door said it was open (and I’m pretty sure they never locked it) I felt like I was breaking the rules by being there. I only ever once saw someone (I assume a professor) and we just quietly, awkwardly avoided each other in the half lit building. Wonderful library though. Had just about any book on Christianity you could imagine. I heard from a seminarian that he’d go sit in the Mary section when he got lonely (which I imagine was a lot). The chapel is hideous. Looks like a prison from the outside, and my understanding is it’s even worse on the inside. There’s a big pond you can walk around, and a basketball court on the far side.

It’s just a very, very strange vibe. Even if there weren’t molesters roaming around, no man should be subject to that life as part of preparation to become a diocesan priest. Vocation to become a Carmelite? Sure.

I knew a lot of the seminarians, and it always seemed like they’d use any excuse to get away. The seminary would do old lady spiritual retreats and stuff like that, because it is a very serene area. But….even if it was a good seminary they should close it down and send the guys elsewhere. I’m sure they could sell the land to a film company to make a horror movie. You could probably keep some of the faculty for it………

The embedded video above is an interview with Stephen Parisi, the dean of seminarians, who quit the seminary last week, alleging widespread corruption there, and in the Diocese of Buffalo. In the clip, he talks about a culture of sexual “blackmail” within the priesthood of the diocese. To be specific, he says that priests stay silent about sexual misconduct and abuse because they are afraid of being exposed.

I’m interested to hear from clerics, seminarians, and others about the culture of formation inside seminaries. You don’t have to be Catholic to weigh in. I’m thinking about a friend who graduated from an ELCA seminary, but who told me a few years ago that the atmosphere there was oppressively woke, and that anyone who didn’t toe the ultra-progressive line was marginalized and silenced.

Advertisement

Yale & The Crisis Of American Elites

Here’s a really important essay by Natalia Dashan, a recent Yale graduate, who says that “the real problem at Yale is not free speech.” It’s an essay about her alma mater, but really it’s about the moral collapse of the American elite. Dashan came from a poor family (they were once on food stamps, she said), and was shocked to find so many truly rich kids at Yale pretending to be poor. Excerpt:

When these kids grow up, they end up at conferences where everybody lifts their champagne glasses to speeches about how we all need to “tear down the Man!” How we need to usurp conventional power structures.

You hear about these events. They sound good. It’s important to think about how to improve the world. But when you look around at the men and women in their suits and dresses, with their happy, hopeful expressions, you notice that these are the exact same people with the power—they are the Man supposedly causing all those problems that they are giving feel-good speeches about. They are the kids from Harvard-Westlake who never realized they were themselves the elite. They are the people with power who fail to comprehend the meaning of that power. They are abdicating responsibility, and they don’t even know it.

Normal class dynamics shouldn’t trouble anyone. It doesn’t do much damage to society for the rich to sometimes hide their status to stay safe, or for the poor to pretend that they are richer than they are to fit in with their idols.

But something else is going on—something more systemic. We mock each other over wealth and mannerisms, to the point that we forget how and why wealth is built in the first place. We forget the extent of our own power and start blaming an ephemeral elite beyond ourselves for the ills of society. And when something does need to be challenged in elite thought, not in the fake, recuperated way that Greta Thunberg ritually challenges an already-supportive crowd at Davos, but in the real way that carries personal risk—we bail. When we see an unfashionable truth that may risk criticism or ostracism, we forget our own position of strength and assume we cannot bear those risks. We give up the fight before it even starts—as if somebody else can or will fight it.

That is what can lead to societal dysfunction. But it is also a symptom of that dysfunction.

Dashan says that we have elites who have power, but don’t know how to use it responsibly. It’s not simply a matter of using it to enrich themselves. Something much weirder is going on. She used the free speech crisis at Yale as a way into the phenomenon. I won’t quote her recap of those events — I wrote about most of them on this blog when they happened — but they had to do with woke students bullying professors, basically, and getting what they wanted out of the spineless administration. She talks about all the good, liberal professors who were abused by these bullies over extremely minor infractions, all with the cooperation of the Yale administration. More:

It doesn’t matter that the ideology is abusive to its own constituents and allies, or that it doesn’t really even serve its formal beneficiaries. All that matters is this: for everyone who gets purged for a slight infraction, there are dozens who learn from this example never to stand up to the ideology, dozens who learn that they can attack with impunity if they use the ideology to do it, and dozens who are vaguely convinced by its rhetoric to be supportive of the next purge. So, on it goes.

This is the nature of coordination via ideology. If you’re organizing out of some common interest, you can have lively debates about what to do, how things work, who’s right and wrong, and even core aspects of your intellectual paradigm. But if your only standard for membership in your power coalition is detailed adherence to your ideology, as is increasingly true for membership in elite circles, then it becomes very hard to correct mistakes, or switch to a different paradigm.

And this helps explain much of the quagmire American elites are stuck in: being unable to speak outside of the current ideology, the only choice is to double down on a failing paradigm. These failures lead to lower elite morale, resulting in the class identity crisis which afflicts so many at Yale. Ironically, the result is an expression of that ideology which is increasingly rigid on ever more minute points of belief and conduct.

Dashan eviscerates these people — those who lead these protests, and those who quietly submit to them — as exhibiting moral cowardice, indeed a moral cowardice that is consequential for the future of society. More:

Shouting from the rooftops that “They aren’t doing enough!” is much easier than following any traditional system of elite social norms and duties, let alone carefully re-engineering that system to reestablish order in a time of growing crisis.

Western elites are not comfortable with their place in society and the responsibilities that come with it, and realize that there are deep structural problems with the old systems of coordination. But lacking the capacity for an orderly restructuring, or even a diagnosis of problems and needs, we dive deeper into a chaotic ideological mode of coordination that sweeps away the old structures.

When you live with this mindset, what you end up with is not an establishment where a woke upper class rallies and advocates for the rights of minorities, the poor, and underprivileged groups. What you have is a blind and self-righteous upper class that becomes structurally unable to take coordinated responsibility. You get stuck in an ideological mode of coordination, where no one can speak the truth to correct collective mistakes and overreaches without losing position.

This ideology is promulgated and advertised by universities, but it doesn’t start or stop at universities. All the fundraisers. All the corporate events. The Oscars. Let’s take down the Man. They say this in front of their PowerPoints. They clink champagne glasses. Let’s take down the Man! But there is no real spirit of revolution in these words. It is all in the language they understand—polite and clean, because it isn’t really real. It is a performative spectacle about their own morale and guilt.

If you were the ruler while everything was burning around you, and you didn’t know what to do, what would you do? You would deny that you are in charge. And you would recuperate the growing discontented masses into your own power base, so that things stay comfortable for you.

Read it all. It’s very, very good.

This is why readers who say that nobody should care what happens on elite campuses are wrong, and foolishly so. Who do you think runs this society? Erich Fromm, in his classic work Escape From Freedom (which explores the psychology of fascism), says that in any society, the views of the power-holding elites set the course for the rest of that society, for the commonsense reason that those elites run the organizations that order the society.

A new survey finds that many hiring managers comb through a potential employee’s social media accounts, and some will not hire someone whose opinions on politics and related matters they find objectionable. Think about that before you post anything controversial. The political and social views of elites matter in all kinds of practical ways. In the workplace, nobody dares to stand against these ideologies for the same reason that nobody stands against them at institutions like Yale: because to object is to draw attention to oneself as a “bigot.” Nobody wants to be the first. As Dashan said, everybody observed what happened to Nicholas and Erika Christakis. Neither the facts, nor their liberal bona fides, nor anything protected them from the ideological mob — a number that included some of their faculty colleagues.

The legal scholar Jonathan Turley flags a particularly egregious instance of this ideologically-driven war on basic standards:

American University has brought in an academic from the University of Washington-Tacoma with a curious mission for an academic institution: to teach academics not to grade on the writing ability of students as opposed to their “labor.” Professor Asao Inoue believes that writing ability should not be assessed to achieve “antiracist” objectives.

Inoue is the director of the UW-Tacoma Writing Center and has explained that “White language supremacy is perpetuated in college classrooms despite the better intentions of faculty, particularly through the practices of grading writing.” It appears that grading on writing ability is one of those acts of white supremacy. He has insisted that professors who use a single neutral standard for all students are perpetuating racism: “[using] single standard to grade your students’ languaging, you engage in racism. You actively promote white language supremacy, which is the handmaiden to white bias in the world.”

You might be thinking, “OK, that’s nuts, but that kind of thing would never fly in STEM disciplines.” Let me introduce you to a peer-reviewed 2017 paper by feminist scholar Donna Riley, who in the same year became head of the Purdue University department of engineering education. Purdue is one of the top engineering schools in the country. Here’s the abstract:

Rigor is the aspirational quality academics apply to disciplinary standards of quality. Rigor’s particular role in engineering created conditions for its transfer and adaptation in the recently emergent discipline of engineering education research. ‘Rigorous engineering education research’ and the related ‘evidence-based’ research and practice movement in STEM education have resulted in a proliferation of boundary drawing exercises that mimic those in engineering disciplines, shaping the development of new knowledge and ‘improved’ practice in engineering education. Rigor accomplishes dirty deeds, however, serving three primary ends across engineering, engineering education, and engineering education research: disciplining, demarcating boundaries, and demonstrating white male heterosexual privilege. Understanding how rigor reproduces inequality, we cannot reinvent it but rather must relinquish it, looking to alternative conceptualizations for evaluating knowledge, welcoming diverse ways of knowing, doing, and being, and moving from compliance to engagement, from rigor to vigor.

In the paper, she writes:

One of rigor’s purposes is, to put it bluntly, a thinly veiled assertion of white male (hetero)sexuality” because rigor “has a historical lineage of being about hardness, stiffness, and erectness; its sexual connotations—and links to masculinity in particular—are undeniable.

Er, right. Here’s a tip for travelers: if you arrive at a bridge over a gorge, you’d better hope that it stands stiff and erect, and that one of Donna Riley’s rigorless students, with their diverse ways of knowing, didn’t have anything to do with engineering the thing.

How does a person of those crackpot views rise to a position overseeing engineering education at one of the country’s top engineering colleges? I think Natalia Dashan has the answer. Donna Riley did not hire herself. Institutional elites whose responsibility it is to affirm and defend standards have morally collapsed in the face of ideological extremism.

One more example: that extraordinary transcript of the in-house “town hall” meeting that New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet held with his staff. I wrote about it last week here. There’s a lot in the transcript that conveys a collapse of professional journalistic standards in the face of ideological extremism, but this is perhaps the most astonishing. These are the opening lines of Baquet’s presentation to his staff, whose concerns about the paper’s coverage of racism and Donald Trump prompted the session. Emphases mine:

If we’re really going to be a transparent newsroom that debates these issues among ourselves and not on Twitter, I figured I should talk to the whole newsroom, and hear from the whole newsroom. We had a couple of significant missteps, and I know you’re concerned about them, and I am, too. But there’s something larger at play here. This is a really hard story, newsrooms haven’t confronted one like this since the 1960s. It got trickier after [inaudible] … went from being a story about whether the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia and obstruction of justice to being a more head-on story about the president’s character. We built our newsroom to cover one story, and we did it truly well. Now we have to regroup, and shift resources and emphasis to take on a different story. I’d love your help with that. As Audra Burch said when I talked to her this weekend, this one is a story about what it means to be an American in 2019. It is a story that requires deep investigation into people who peddle hatred, but it is also a story that requires imaginative use of all our muscles to write about race and class in a deeper way than we have in years. In the coming weeks, we’ll be assigning some new people to politics who can offer different ways of looking at the world. We’ll also ask reporters to write more deeply about the country, race, and other divisions. I really want your help in navigating this story.

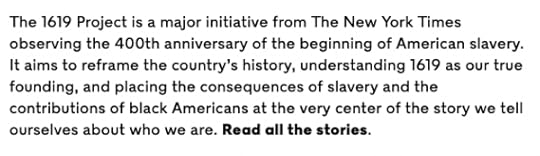

Get that? Baquet said that the Times oriented its entire newsroom to covering the Russia collusion story, and now it’s doing the same thing to cover race and Trumpism. We are going to hear from now through Election Day a steady drumbeat of stories from the Times about how Trump and everything associated with him is racist. This is not right-wing paranoia; this is the most rational conclusion from the recent words of the executive editor of The New York Times — a newspaper that publicly states that the arrival of the first African slave is the “true founding” of America. Seriously, this is a screenshot from the paper’s webpage:

I can hear some of you now: “Oh, who cares what the New York Times thinks! Only the elites read it.” Yes, exactly. As professional journalists know, the Times, even more than the Washington Post, is the standards-setter for American journalism, both print and broadcast. It is also the newspaper of record for academic and cultural elites. The main reason I subscribe to it is for the same reason that Cold War Kremlinologists read Pravda: to know what those elites are thinking. I’m actually not joking. The Times‘s advocacy pieces on things like the travails of gender nonbinary people may puzzle most people, who might see it as a larky manifestation of Manhattan obsessions. But you can be sure that editors at newspapers around the country are observing these things, and making decisions to cover — sympathetically, always sympathetically — the same phenomenon locally. You will not see in the Times, or in any other media outlet following the Times, anything critical of this trend. Soon, the message will be received by elites, and those who wish to achieve power, that objecting to any of this, on any grounds at all, is taboo.

This is how cultural change happens. As Natalia Dashan wrote about Yale:

You get stuck in an ideological mode of coordination, where no one can speak the truth to correct collective mistakes and overreaches without losing position.

As regular readers know, I’m researching and writing a book about the rise of what I call “soft totalitarianism.” It’s not going to be a book about Socialism 2.0, though I concede an earlier iteration was closer to that than where I am now. Most of the same fundamental conditions that gave rise to 20th century totalitarianism exist now. (I’ve been reading Fromm’s 1941 book this weekend, and it’s unnerving to see this.) As far as I can tell, we have two major factors today that did not exist before:

Staggering technological capabilities to surveil individuals at intensely granular levels, and an unprecedented capacity to modify behavior. This has not been imposed on a servile populace by a totalitarian government, but has been developed by capitalists, and welcomed by consumers.

A power elite that adheres to radical identity-politics ideology, and that will use its power and privilege to promote that ideology, and to demonize any challengers to it.

Our old 20th-century ways of thinking blind us to what’s happening. For example, we think of totalitarianism as something imposed from above; read Shoshanna Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism and Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus to cure yourself of that illusion. (Note well: you don’t have to agree with all the conclusions of Zuboff and Harari to be deeply challenged by their takes on how we have welcomed technologies into the most intimate parts of our lives.) And take up the novels of Michel Houellebecq, if you can stomach them (I can). If we’re bound by 20th-century categories, we think that Government is the Bad Guy, and Business is the Good Guy (or, if you’re on the left, vice versa). That’s how we’re blindsided by Woke Capitalism.

But I digress, as usual. The point is, read Natasha Dashan’s essay. Again: the crisis at Yale matters because, as she says, the crises at top colleges determine what is acceptable for everybody else. That’s just how societies work. And, the crisis at Yale is a particularly acute version of a crisis in the American leadership class. Dashan writes:

Yale is having an existential crisis. Students are taught to break the system, but Yale doesn’t even want to teach them what the original system is, what it was for, or how to productively replace it. The university is so lacking in vision that it doesn’t even know what the ideal student looks like, or what it wants to teach them.

Maybe the university has lost every purpose other than giving students a social environment in which to party. If the students aren’t educated or visionary, at least they’re networking and hedonically satisfied.

Except they’re not. It would be one thing if they were happy—but even this is not true. They don’t know what is expected of them, or what they should aspire to be. The lack of expectations creates nihilistic tendencies and existential crises. In 2018, around one quarter of Yale undergraduates said they sought mental health counseling. One quarter of Yale students took the “Happiness and the Good Life” course in 2018 in an attempt to find answers. Students are demanding more mental health resources. A new wellness space was created with bean-bag chairs and colored walls. But the real sources of unhappiness are more systemic. They are rooted in uncertainty about the future.

If Yale students are uncertain about the future and their role in it, what does that say about the rest of society?

Indeed. It took the daughter of immigrants, a Yale graduate who was once on food stamps, to provide this astonishing analysis of an institution she clearly loves. Readers, don’t sit back and take populist satisfaction in this crisis. Every society has to have a leadership class. As Dashan points out, Yale has a very deep bench, and (for one) provides many of our Supreme Court justices. If our US leadership class is corrupt in important ways — “Look, the head of engineering education at an important US engineering school thinks rigorous engineering is bigoted!” “Look, the executive editor of The New York Times is building his entire newsroom to promote an ideological narrative!” “Look, a celebrated academic is teaching that clear writing is racist!” etc. — somehow, they will be replaced. The bridges (so to speak) will fall down, and society will need leaders that can rebuild them. Are you quite sure that those who will replace these elites will be an improvement?

I wonder what the power elites of the Weimar Republic would have to tell us about that.

UPDATE: Today’s NYT entry in its “1619” project: