Rod Dreher's Blog, page 194

November 12, 2019

‘What’s The Matter With Conservatives?’

Writing in The Atlantic, Yoni Appelbaum offers a provocative essay whose thesis is that the US is in for a period of great political turmoil as the percentage of whites declines, and the Republican Party in turn loses power. He writes, in part:

What has caused such rancor? The stresses of a globalizing, postindustrial economy. Growing economic inequality. The hyperbolizing force of social media. Geographic sorting. The demagogic provocations of the president himself. As in Murder on the Orient Express, every suspect has had a hand in the crime.

But the biggest driver might be demographic change. The United States is undergoing a transition perhaps no rich and stable democracy has ever experienced: Its historically dominant group is on its way to becoming a political minority—and its minority groups are asserting their co-equal rights and interests. If there are precedents for such a transition, they lie here in the United States, where white Englishmen initially predominated, and the boundaries of the dominant group have been under negotiation ever since. Yet those precedents are hardly comforting. Many of these renegotiations sparked political conflict or open violence, and few were as profound as the one now under way.

Within the living memory of most Americans, a majority of the country’s residents were white Christians. That is no longer the case, and voters are not insensate to the change—nearly a third of conservatives say they face “a lot” of discrimination for their beliefs, as do more than half of white evangelicals. But more epochal than the change that has already happened is the change that is yet to come: Sometime in the next quarter century or so, depending on immigration rates and the vagaries of ethnic and racial identification, nonwhites will become a majority in the U.S. For some Americans, that change will be cause for celebration; for others, it may pass unnoticed. But the transition is already producing a sharp political backlash, exploited and exacerbated by the president. In 2016, white working-class voters who said that discrimination against whites is a serious problem, or who said they felt like strangers in their own country, were almost twice as likely to vote for Trump as those who did not. Two-thirds of Trump voters agreed that “the 2016 election represented the last chance to stop America’s decline.” In Trump, they’d found a defender.

Appelbaum makes the usual argument that if the Republicans don’t find some way to appeal to Americans beyond its white Christian base, it will be inevitably doomed, owing to demographic change. Republicans don’t see this, he says, and are doubling down on identity politics. He writes:

The GOP’s efforts to cling to power by coercion instead of persuasion have illuminated the perils of defining a political party in a pluralistic democracy around a common heritage, rather than around values or ideals.

Read the whole thing.It’s good, and the demographic problem for Republicans that he writes about really is undeniable. But the essays blind spots are at least as illuminating as its strengths.

By now we should all be aware that in general, conservatives understand liberals better than liberals understand conservatives. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt wrote about why this is so. It’s not that every conservative understands every liberal better than the opposite; it’s a general trend, and it has to do, says Haidt, with different moral frameworks that we work into our psychology.

What I find so telling about Appelbaum’s essay is that he assumes that Republicans are the only ones practicing identity politics, as opposed to appealing to “values and ideals.” He apparently doesn’t see that the “values and ideals” promoted by liberals, and the Democrat Party, are explicitly or implicitly anti-white, anti-Christian, and anti-male. Obviously liberals don’t see it that way; what they call “diversity and inclusion,” we conservatives recognize clearly as left-wing identity politics aimed to exclude and disempower us. Remember earlier this year, rising Democrat Stacey Abrams, an African-American, said that her party should not pretend it doesn’t practice identity politics, because “identity politics is exactly who we are.”

I don’t know why an essayist as intelligent and as perceptive as Appelbaum can’t see what the world looks like to Christian conservatives like me. I wouldn’t expect him to share my point of view, as he is neither Christian nor conservative, but when we look out at the world, we see not simply a world in which we are not in power, but one in which people who regard us as evil and actively seek to punish us are coming into power. I know plenty of highly educated Christian conservatives with whom Appelbaum could have a deep, rich discussion about any number of topics, who are at ease with pluralism, and who think Donald Trump is a disgrace … but who are probably going to vote for him in 2020, because they understand well what a Democratic Party victory means for them. Most of these people are academics, and are small minorities within their professional milieux. They see up close and personal what’s coming for people like them.

My point here is simply that the demographic changes Appelbaum correctly cites as having a tectonic shift in American politics tell a far more complex story than he allows for. I do not see the Left as standing for ideals, as opposed to ethnic and identity-politics interests. The Democratic Party is far more an identity-politics party than the Republicans are, though this is not the narrative we get in the media, which is overwhelmingly liberal. Look, I’m not going to say that Republicans don’t play identity politics. They do — but all political parties do. I hope I don’t sound like a vulgar Marxist, but it really is true that sometimes, power-holders and power-seekers drape class interests in gauzy veils of moral idealism. I think Appelbaum completely misses the extent to which the Democratic Party has become aggressively hostile to those who don’t share its core ideals — and, in turn, how they too are driving the turmoil.

I want to go back to this observation by Appelbaum:

The GOP’s efforts to cling to power by coercion instead of persuasion have illuminated the perils of defining a political party in a pluralistic democracy around a common heritage, rather than around values or ideals.

This is awfully rich coming from someone within a political tradition whose most progressive, active wing constantly attempts to silence dissent on campuses. More importantly, it’s just not an accurate description of our situation. As far back as 1981, Alasdair MacIntyre observed that emotivism — a view that entails the substitution of emoting for reasoning — is the dominant driver of contemporary discourse. We all do this! Appelbaum’s argument reminds me of an exchange I had back in the 1980s with an elderly relative in my hometown, speaking about local politics:

Him: “The problem with the black folks around here is that they always bloc-vote for candidates.”

Me: “But white folks do the same thing.”

Him: “No we don’t. We always vote for the most qualified candidate.”

Me: “Who always happens to be the white one.”

He did not understand what I was getting at. To him, the political choices of white people were always well-reasoned, while blacks were the ones who voted on emotion. He was right: black voters in our parish bloc-voted for the black candidate, if there was one, or the white candidate that their pastors endorsed. White voters bloc-voted for the white candidate, if a black one was the opponent. If the candidates were all white, then it didn’t matter. Because of his own prejudices, my relative genuinely didn’t understand that white voting was every bit as emotivist as black voting. I think Appelbaum is making the same mistake from the other side in his essay.

The truth is, we are probably moving into a political world of irreconcilable differences. It is hard to see on what basis we could find political compromise, given how extreme people in both parties (as Appelbaum notes) regard the political other. Conservatives like me, who are accustomed to working in liberal spaces, are familiar with the unreflective liberal stance holding that the only reason conservatives don’t agree with liberals is irrational prejudice — in which case I would ask: Who is doing the emoting here, instead of reasoning?

Side note: The other day, I heard a very long NPR interview with LA Times reporter Gustavo Arellano, talking about the effects of Prop 187, the controversial 1994 California measure that prohibited illegal immigrants from receiving public services. Arellano, who’s a good writer and a great radio talker, spoke of it solely from a Latino point of view, as a moment of anti-GOP political awakening. I have no problem with Arellano speaking his opinion about this, of course, but if you go to NPR’s website, you’ll see that they had no interest in speaking with a conservative about Prop 187 (which died in a court challenge), and the subsequent demise of the GOP, and the overwhelming of the state by immigrants. If you read California scholar and writer Victor Davis Hanson on how immigration has changed the state, you’ll hear a fascinating counternarrative. But NPR — Diverse And Inclusive — doesn’t want to hear that. It knows who is right, and who doesn’t deserve to be heard from, because they are on the wrong side of history.

— doesn’t want to hear that. It knows who is right, and who doesn’t deserve to be heard from, because they are on the wrong side of history.

Sure, this is just one small example of the kind of thing conservatives are used to from our media. But it reveals to me the hidden biases in the diagnosis of even someone as smart as Yoni Appelbaum. To wrap up: he’s correct to point out that the GOP, and American conservatism, has a big demographic problem. But he’s very wrong to assume that Republicans and conservatives are reacting irrationally and emotionally to this crisis. In fact, a lot of what Republicans and conservatives do is reasonable in light of the policies and acts of Democrats and liberals. It ain’t paranoia if they really are out to get ya.

The post ‘What’s The Matter With Conservatives?’ appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 11, 2019

The ‘Evil’ First Amendment

First, let me quote to you something from The Captive Mind, Polish dissident writer Czeslaw Milosz’s 1951 classic exploring the mentality of intellectuals who submitted to Communism:

It was only toward the middle of the twentieth century that the inhabitants of many European countries came, in general unpleasantly, to the realization that their fate could be influenced directly by intricate and abstruse books of philosophy. Their bread, their work, their private lives began to depend on this or that decision in disputes on principles to which, until then, they had never paid any attention. In their eyes, the philosopher had always been a sort of dreamer whose divigations had no effect on reality. The average human being, even if he had once been exposed to it, wrote philosophy off as utterly impractical and useless. therefore the great intellectual work of the Marxists could easily pass as just one more variation on a sterile pastime. Only a few individuals understood the causes and probably consequences of this general indifference.

The more general point here is that ordinary people had better pay attention to what intellectual elites say and do. It is very, very unwise to laugh them off as living in an ivory tower. The lightning-fast movement of what was once ultra-fringe discussions about gender and sexuality from graduate student seminars to the center of American culture is a clear and unmistakable sign — and a warning. What happens at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and other elite universities does not stay there. The people those universities educate become the American elites, and move into leadership positions throughout US society.

I mentioned this summer being in Poland, and talking with Poles who work for the Polish branches of US and Western Europe-based multinationals. Those companies are bringing LGBT Pride policies and initiatives into their Polish workplaces. The Poles with whom I spoke are Catholics whose religious convictions rebel against having to affirm LGBT — especially the T — in the workplace. But they badly need those jobs, so they’re torn. In this way, US and Western European corporate elites are compelling a cultural revolution. If they succeed in changing the views of Eastern European elites, then they will change those countries. What started in American universities will have made its way down to everyday life in Poland and countries like it. It never would have occurred to Polish workers that the abstruse theories of, say, Judith Butler would have anything to do with their jobs, but that’s exactly what is happening, right now, all over the world.

Similarly, in a fantastic history I’m reading now, Yuri Slezkine’s The House Of Government, it is clear that the ideas that led to the Bolshevik Revolution, and ultimately the deaths of 20 million, began in fervent reading groups of messianic young Marxist intellectuals. People who do not pay attention to what intellectual and cultural elites say, or who dismiss it as eggheaded nonsense, are fools.

I say that as background to the latest insanity from Harvard, as reported by The Harvard Crimson:

Harvard’s Undergraduate Council voted to pass a statement at its meeting Sunday in support of immigration advocacy group Act on a Dream’s concerns about The Harvard Crimson’s news policies and made recommendations to make reporting policies more transparent.

The statement, passed 15-13-4, comes after The Crimson covered Act on a Dream’s “Abolish ICE” protest in September. After the protest, Crimson reporters contacted a United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement spokesperson for comment. More than 900 people and several student groups have since signed an Act on a Dream petition condemning The Crimson’s decision to reach out for comment.

The council’s vote approved its own statement regarding the issue to be sent out to students in its weekly email.

“The Undergraduate Council stands in solidarity with the concerns of Act on a Dream, undocumented students, and other marginalized individuals on campus,” the statement reads. “It is necessary for the Undergraduate Council to acknowledge the concerns raised by numerous groups and students on campus over the past few weeks and to recognize the validity of their expressed fear and feelings of unsafety.”

Members of several campus groups including Act on a Dream and the Harvard College Democrats have instructed their members not to speak to The Crimson unless it changes its policies.

You see what’s happening here? These Harvard students, and part of the Harvard student government, do not want the campus newspaper to practice basic journalism. It condemns the newspaper simply for seeking comment from people the students dislike. The agents of ICE are non-persons — people so horrible that they do not deserve to be heard, because they cause members of favored groups to experience “feelings of unsafety.”

The First Amendment to the US Constitution guarantees free speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of religion. It is perhaps understandable (though not defensible) that elite Harvard students would oppose freedom of religion. But freedom of the press? If they’re against basic journalistic standards, this is a terrible sign for the future, and for all the First Amendment freedoms. A couple of weeks ago, a poll came out showing that 60 percent of young Americans want the First Amendment rewritten to restrict free speech and freedom of the press. (And yes, I am aware that Donald Trump’s appalling populist rhetoric about the press is adding to this hatred of the First Amendment.)

The book I’m writing now talks about the cult of Social Justice, and the messianic, militant utopianism of this new generation of progressives, who are marching through the institutions of American life. I’m thinking hard right now of this other line from Milosz’s book, about the insufficiency of making better arguments than the enemies of liberty. The “Messiah” he mentions here is Communism:

One does not defeat a Messiah with common-sense arguments.

UPDATE: At Northwestern University, home of one of the country’s leading journalism schools, the campus newspaper’s leadership has capitulated to the SJWs. In this editorial, they apologize to the campus for reporting on a public event (a speech given on campus by former AG Jeff Sessions). Excerpt:

We recognize that we contributed to the harm students experienced, and we wanted to apologize for and address the mistakes that we made that night — along with how we plan to move forward.

One area of our reporting that harmed many students was our photo coverage of the event. Some protesters found photos posted to reporters’ Twitter accounts retraumatizing and invasive. Those photos have since been taken down. On one hand, as the paper of record for Northwestern, we want to ensure students, administrators and alumni understand the gravity of the events that took place Tuesday night. However, we decided to prioritize the trust and safety of students who were photographed. We feel that covering traumatic events requires a different response than many other stories. While our goal is to document history and spread information, nothing is more important than ensuring that our fellow students feel safe [emphasis mine — RD] — and in situations like this, that they are benefitting from our coverage rather than being actively harmed by it. We failed to do that last week, and we could not be more sorry.

Some students also voiced concern about the methods that Daily staffers used to reach out to them. Some of our staff members who were covering the event used Northwestern’s directory to obtain phone numbers for students beforehand and texted them to ask if they’d be willing to be interviewed. We recognize being contacted like this is an invasion of privacy, and we’ve spoken with those reporters — along with our entire staff — about the correct way to reach out to students for stories.

It goes on. It’s a signed editorial, which I suppose gives future employers a heads-up about these young fraidy-cats’ complete lack of moral courage and journalistic professionalism.

UPDATE.2: A young journalist quotes the signatories of the editorial and warns about what’s coming when this generation (his own) takes institutional power:

The post The ‘Evil’ First Amendment appeared first on The American Conservative.

The Trial Of Conservative Catholicism

Well, Your Working Boy is back from Russia, and has mostly, but not completely, got his sleep chakras re-aligned, so blogging in this space will return to normal. Pretty much — as you can see, TAC underwent a redesign over the weekend, and like the brand-new terminal at the New Orleans airport, it’s going to take a bit to work out the kinks. (True story: my connecting flight from Miami landed just before midnight, but the captain told us that we would have to sit on the tarmac for a bit, because nobody at the airport thought to prepare a jet bridge for us.) Anyway, please bear with us as we get used to the new system. One important format change: on the old site, I would post the more minor entries of mine onto my blog alone, and not put them on the front page. That’s not possible with this new site; everything goes to the front page. That might not matter to your viewing experience, but in case it does, now you know.

So, let’s get back into things, shall we?

Yesterday, Ross Douthat published what amounts to crack for poor religious-news nerds like me, who can’t stop thinking about the meaning of the self-deconstruction of the Catholic Church under Pope Francis. Douthat wrote a column about the plight of conservative Catholics under Francis, and supplemented it with a long interview with Cardinal Raymond Burke, who has emerged as Francis’s chief opponent (though Burke understandably disputes some characterizations of their relationship).

Let’s start with the column. Douthat — who identifies as a conservative Catholic — writes that in the wake of the Amazon Synod, it has become clear that Francis is routing his opposition:

As conservative resistance to Francis has grown more intense, it has also grown more marginal, defined by symbolic gestures rather than practical strategies, burning ever-hotter on the internet even as resistance within the hierarchy has faded with retirements, firings, deaths.

In his interview with Cardinal Burke, the prelate lays out a case in which Burke and his allies are being faithful to the Catholic tradition, but the Pope is not. From what I can see as an ex-Catholic outsider, Burke is right about that … but in the real world, that is an irrelevant distinction. As Douthat writes:

But you can also see in my conversation with the cardinal how hard it is to sustain a Catholicism that is orthodox against the pope. For instance, Burke himself brought up a hypothetical scenario where Francis endorses a document that includes what the cardinal considers heresy. “People say if you don’t accept that, you’ll be in schism,” Burke said, when “my point would be the document is schismatic. I’m not.”

But this implies that, in effect, the pope could lead a schism, even though schism by definition involves breaking with the pope. This is an idea that several conservative Catholic theologians have brought up recently; it does not become more persuasive with elaboration. And Burke himself acknowledges as much: It would be a “total contradiction” with no precedent or explanation in church law.

Douthat goes on to lay out what he sees as the possible strategies open to conservative Catholics now. The first two are implausible, or at least deeply unsatisfying, and will require Olympic-class mental gymnastics to affirm. The final one — simply waiting, and suffering — seems to me to be the only reasonable one left to those Catholics who still want to remain in communion with Peter’s successor, which is core doctrine that defines the Roman Catholic Church.

Reading Douthat’s column, I think of a conservative Catholic friend of mine who came out on Saturday to see me speak on a panel at the Catholic center at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette. We spoke briefly before my talk; I hadn’t seen him in ages. I asked him how he was doing with the chaos in the Catholic Church. “Man, I don’t pay attention to it,” he told me. “I’m just focused on my parish, and doing the best I can with the people around me.” I think this is a wise approach; it’s the approach I took to Orthodoxy after I burned out on Catholicism. But it was startling to me to hear this old friend, who used to be a fierce culture warrior within the Catholic Church, talk like this. I’m sure that neither of us ever imagined that the Catholic Church would find itself in this condition, not in our lifetimes. But then, we were both acculturated to Catholicism in the age of John Paul II and his great ally, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Benedict XVI.

For many of us, to become a Catholic in the Wojtyla years — me, as an adult convert; my Catholic-born friend, as a baptized Catholic who rediscovered his childhood faith in a passionate, born-again way in adulthood — was to be drawn to the Catholic Church as a solid rock standing firm in the raging river channel of liquid modernity. I recall my own initial moves toward Catholicism in my early twenties. I went to an Episcopal church for a little while, figuring that I could have the aesthetic parts of the Catholic liturgical tradition, which I liked, without the unpleasantly rigorous parts having to do with sex. I realized eventually that this was unsustainable, for several reasons. If I was willing to accept a rejection of Biblical teaching and longstanding tradition on sexual matters, because it suited what I preferred to believe, then where was it possible to draw a line? What possible barrier against radical innovation was there?

Because I knew nothing about Orthodoxy back then, the only possible destination for me was within Catholicism. Besides, I wanted to be Catholic deep down; I was just scared of its demands. I had gone to see John Paul in the New Orleans Superdome in 1987, drawn by the charisma of that great man of God. He was the spiritual father that I longed for: morally and theologically serious, but compassionate and merciful. I thought that John Paul II was what Catholicism was. And I became Catholic in 1993.

There’s no need to repeat again in this space the process of my disillusion, which is familiar to regular readers. I will say, for purposes of this post, that unlike the situation with Francis, it had nothing to do with doctrine. I simply found myself overwhelmed by the evil of the abuse scandal, and the stubborn indifference of the corrupt Catholic hierarchy to the pain and injustice priests wreaked on children and families. I know, I know: the sins of the clergy do not negate the truth of the teachings. I told myself that too, over and over, and it kept me Catholic for a while. What I did not anticipate was something phenomenological about religious belief: that faith is not something that can be commanded as the inevitable consequence of a series of correct premises. I remember the hour I first disbelieved, when the dam I had built to hold back the mounting doubt, carried on a flood of rage, cracked and collapsed. Once that happens — and pray it doesn’t happen to you — there are no syllogisms that can recall the torrent.

I approached Orthodoxy from the beginning, and still do, with humility. I once thought of myself as the kind of Catholic whose faith was unshakable. I was intellectually prideful, and triumphalist, and God allowed me to be smashed on the rocks of my arrogance. I told this story to an Orthodox audience at a church in Moscow last Sunday, and warned them that this kind of thing could happen to any Christian, in any church. One great gift Orthodoxy has given me has been its focus on conversion of the heart. Orthodoxy certainly believes that the mind is important, and must also be converted. But first comes the heart. This is something I didn’t fully appreciate as a Catholic, and it allowed me to set myself up for a great fall, because I had such supreme confidence in Reason, and the intellect.

The Catholic Church did not teach me to be so triumphalistic; it was my fault, but it was a fault shared by a number of young, or young-ish, JP2 Catholics, all of us male. Once a professor told me that as a graduate student, he was drawn to the Catholic faith, but the arrogance of his Catholic friends kept him away. He explained that these young intellectuals were so certain of the correctness of Catholicism that they spoke of Christians in other traditions with barely-concealed disdain. I winced when I heard him say that, because I know that that was me once upon a time. Part of my disdain, I must confess, was thinking that the poor Protestants are so lost, without a Magisterium and a Pope to guard the teachings against the modern Zeitgeist.

Because of that, I know that even if my Catholic faith had survived the great trial by fire of the scandal, I would be facing a different severe test now, with the Francis papacy. The abuse scandal involved a radical betrayal by the clerical class of the Church’s teachings, but it did not entail a formal negation of those teachings. The Francis papacy does, or so it seems to me. What he is doing was supposed to be impossible, according to the things I believed as a conservative Catholic. This morning I’m thinking back on that restless seeker that I was in the early 1990s, and how much the stability of the Catholic Church appealed to me, and I’m wondering what I would have done had I been able to foresee a pope like Francis.

To be clear, I don’t think there is any “safe space” — an unbreachable fortress — from modernity in any church, though Orthodoxy is by far the strongest, in my experience. When I was Catholic, I used to wonder how Orthodoxy was going to stay so traditional, lacking laws and a clear teaching authority as well articulated as in Catholicism. Now, having been Orthodox for as long (13 years) as I was Catholic, I see that this is actually an advantage. Of course Orthodoxy is hierarchical, and has canon law, but the weight of tradition is monumental. Innovators within Orthodoxy lament how difficult it is to change anything major, given the requirement of an ecumenical council to make this happen (and we haven’t had one of those in over 1,000 years). But in liquid modernity, I think this is a vital safeguard. As a Catholic, it’s important to pay attention to your bishop, and to the Pope, because in modern times, they can change a lot, either by what the Church’s authorities choose to do, or what they choose not to do. As Cardinal Burke said in his interview with Douthat:

Douthat:How would you distill your critique of how the pope is handling the debates he’s opened?

Burke: I suppose it could be distilled in this way: There’s a breakdown of the central teaching authority of the Roman pontiff. The successor of St. Peter exercises an essential office of teaching and discipline, and Pope Francis, in many respects, has refused to exercise that office. For instance, the situation in Germany: The Catholic Church in Germany is on the way to becoming a national church with practices that are not in accord with the universal church.

Douthat:Which practices?

Burke: Calling for a special rite for people of the same sex who want to marry. Permitting the non-Catholic party in a mixed marriage to regularly receive the Holy Eucharist. These are very serious matters, and they’ve basically gone unchecked.

Douthat:But isn’t the decision of when to exercise authority inherent in the pope’s authority itself? Why isn’t it within his power to tolerate local experiments?

Burke: He really doesn’t have a choice in the matter if it’s a question of something contrary to the church’s teaching. The teaching has always been that the pope has the fullness of power necessary to defend the faith and to promote it. So he can’t say, “This form of power gives me the authority to not defend the faith and to not promote it.”

I would say that Cardinal Burke is correct … but that it doesn’t matter. This is not something we Orthodox have to worry about — truly, I would not be able to recognize my bishop if I passed him on the street — because we can have confidence that the teaching is not going to change.

But! If you had asked me in 1993, as a new Catholic, if the Catholic Church’s teachings were going to change, in the way Francis is changing them, I would have dismissed it as an absurd question. Yet here the Catholic Church is, in 2019. I think it is a very, very bad idea for any Christians, no matter what their confession, to be complacent. As someone — Peter Maurin? — once said, it is impossible to create a system so perfect that man does not have to be good. It is impossible to create an ecclesial system so perfect that striving for personal holiness is anything but at the core of the church’s mission.

I mentioned the other day that in Russia, I was blessed to discover father-and-son saints, the priests Alexei and Sergei Mechev, who served in the same Moscow parish. In 1931, Father Sergei sent this letter to his parishioners, after the Bolsheviks closed down their church. In the 1931 letter, Father Sergei recalled the 19th century prophecies of Orthodox holy men, who warned that the spiritual rot inside the Russian Orthodox church was calling down a severe judgment from God:

The judgement of God is taking place upon the Russian Church. It is not by coincidence that the external aspect of Christianity is being taken away from us. The Lord is punishing us for our sins, and thereby is leading us towards a cleansing. What is happening is unexpected and incomprehensible for those living by the standards of the world. Even now they still strive to bring everything down to an external level, attributing everything to causes which lie outside the Church. Yet, those who live for God have had everything revealed to them long beforehand. Many Russian ascetics not only foresaw these dreadful times, but also witnessed about them.

Not in the external aspect did they see a danger for the Church. They saw that true piety is abandoning even the monastic centers; that the spirit of Christianity is departing in an undetectable way; that the most terrible famine is upon us—famine for the Word of God; that those who possess the keys to unlock this knowledge are not letting others enter; and that with the seemingly abundant monastic prosperity, Christianity is at the last breath of life. Abandoned is the path of experience and activity, by which the ancient fathers lived and which they passed on in their writings. There is no mystery of the interior life, for “the venerable ones have departed, and the truth has left the sons of mankind.” From the outside there has begun a persecution of the Church, and the present reminds us of the first centuries of the Christian era. The Blessed Hierarch Philaret of Moscow, more than once in his talks with those close to him in spirit, pointed out that the time is long overdue for Russia to be in the same position as the ancient Christianity of the first centuries. He wept for the children who are to behold even worse things. The revelation about our time is especially well expressed by two hierarchs who have studied diligently the Word of God: Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk [+1783] and Bishop Ignatius Brianchininov [+1867].

“At present true piety has almost vanished, and we are left with only hypocrisy,” said Saint Tikhon about the state of the Church in his time. He predicted the vanishing of Christianity in an unseen way due to the people’s indifference to it. He warned that Christianity—being life, mystery and spirit—should not perish unnoticed from those who do not value this priceless gift of God. A century after him, Bishop Ignatius Brianchininov spoke of monasticism and the Church and defined their state: “We are living in turbulent times—the venerable ones have left the earth, and truth has become scarce amidst the sons of mankind. A famine for the Word of God has arrived; the keys to unlock this knowledge are in the hands of the Scribes and Pharisees and they are themselves not entering and not letting others enter. Christianity and monasticism are at their last breath. The image of Christian piety is at best being kept only in a hypocritical way. All strength for true piety has left, people have given up; one must weep and be silent” (Letters, 15).

Seeing in monasticism the barometer of the spiritual life of the entire Church, Bishop Ignatius claims the following about its condition: “One can admit that the consummation of the witness of the Orthodox Faith is coming to a final unwinding. The fall of monasticism is significant, and what will happen is unavoidable. Only the mercy of God can stop the morally corrupting epidemic. Perhaps it will stop it only for a short time, for the prophecies of the Scriptures must be fulfilled” (Letters, 245).

“With a sorrowful heart I behold the unstoppable fall of monasticism, which is the sign of the end of Christianity” (Letters, 251).

“The more time that passes, the more turbulent it is for Christianity as spirit, which in a way unseen by the vain and worldly masses—but clearly revealed to the one who struggles in himself—is departing from the heart of mankind, leaving everything ready for its destruction. —Those who are in Judea must run for the mountains” (Letters, 118).

Many of the ascetics of the 18th and 19th centuries looked upon the time of their lives as a period of calm before the storm for the Church of Christ. We must not forget that all this was said by them in times of complete external prosperity. Monasteries not only existed, but were well endowed; new monastic communities were constantly being formed; new churches were built; ancient ones were restored, renovated and rebuilt; and the relics of saints were revealed. The Russian people were praised as guardians of purity in Orthodox faith and genuine piety. No one could have ever perceived that the Church was in a critical state and the end was not beyond the hills. Only those who had come to the knowledge of the Kingdom of God, possessing it in their hearts, could perceive otherwise. With a heavy heart they beheld all that went on around them and, not finding the life given by Christ in what they saw, they predicted a final catastrophe.

“Only a special mercy of God can stop such a thing for a short time,” said Bishop Ignatius Brianchinininov.

Within a decade, faithful Father Sergei was sent to the gulag, where he perished. A few years back, he was canonized as a martyr.

Though I look at the agonies my brothers and sisters in the Catholic Church are suffering now, I don’t in any way take comfort in the fact that Orthodoxy is immune, or largely immune, from that kind of thing. For one thing, I have lived through how fast things can change, in ways that faithful believers cannot anticipate. For another, as St. Sergei reminds us Orthodox, God does not reward us for having preserved a structure of orthodoxy; he rewards, or punishes, us for the condition of our hearts.

It’s strange, but in Russia, I had kind of expected to have conversations with informed Christians about what was going on in the Western churches, especially with the Pachamama Synod having just concluded in Rome. I met not a single Orthodox Christian who had any real idea what was happening in the West. We are as foreign to them as they are to us. They are preoccupied with the schism between Moscow and Constantinople, and the ecclesial mess in Ukraine. That, and what I heard from some Orthodox laymen is frustration with the institutional church’s worldliness, and inability to reach the younger generations, who have become cynical about the Church as an apparatus of state power.

I want to be very clear here: I am so, so grateful for the gift of Orthodoxy! Especially after this recent trip to Russia, I am overwhelmed by God’s mercy to me by rescuing me from the miry pit, and restoring me to himself in Orthodox Christianity. The severe mercy God gave me, though, was to purge me of the temptation to spiritual pride in things of the Church. Not one confession on the face of the earth today is without serious problems. Orthodox triumphalism is no more warranted today than my Catholic triumphalism was in the 1990s. (And, if you’re an Evangelical or some other kind of Protestant tempted to triumphalism, you are living in a bubble.) I’ve recently discovered the blog of an unidentified Orthodox Christian woman who converted out of Catholicism. She used to be quite liberal, but now accepts the teachings of the Orthodox Church (and, apparently, had come to accept traditional Christian teaching on sexuality while still a Catholic). She writes in a post titled “The Sane Traditionalist”:

I converted to Eastern Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism, and came to Catholicism from a Southern Baptist upbringing with a very long detour through modern paganism. By the time I was confirmed a Catholic I had made peace with orthodox Christian social teaching: the sanctity of marriage, the unique gifts of men and women respectively, the sanctity of life, and the sacredness of sexuality. For someone who used to describe herself as a sex-positive, pro-abortion LGBTQI ally, this was not a small thing and required a lot of soul searching and prayer.

In this process of awakening and self-discovery I was determined not to shun my progressive, gay, lesbian, and transgender friends, but I needn’t have worried. They abandoned me, with the exception of the few who felt that telling me my faith in Christ was despicable was their duty.

Finding a home in Eastern Orthodoxy hasn’t exactly solved all of these issues. The church, like the culture, is full of progressives and traditionalists. And while Orthodoxy is thoughtful and beautiful and merciful, these politicized issues can still feel like a sports rivalry rather than a matter of spiritual discernment. And remaining in a place of love and compassion is no easier here than in any other faith tradition.

What a challenge we have in this moment in time, to hold onto the traditional, orthodox teachings of our religious culture when the world perceives those teachings as despicable. When some of our brothers and sisters in faith see them as obsolete and abhorrent. When some who worship with us use sacred and holy things to bludgeon, taunt, and mock their more progressive spiritual family.

So how can you be a sane traditionalist in a world gone crazy? I try to hold onto the idea that Orthodoxy is a way of living where tradition is tempered by mercy, and I cling to the idea that of all sinners I am first. I am the worst sinner I know because I am the sinner I know best. It makes for a delicate dance: to love, respect, and have compassion for people with beliefs you are convicted are wrong, and yet stand firm in the hard-won and time-tested values of your ancestors.

There is wisdom in that for all of us conservative/traditionalist types in this time of decadence. We should also remember, per St. Sergei’s citation of the 19th century fathers, that even the past, when things were more solid on the surface, were times of turmoil and falling-away. Maybe St. Sergei’s father, St. Alexei, is a good saint for all faithful anti-modernist Christians in the present moment. Here’s a biography of him. He was a priest in the little parish on Maroseyka Street in Moscow, and did not meet with success at first:

Fr. Alexey’s success did not blossom overnight. Describing the early years of his pastorate he said:

“For eight years I served the Liturgy daily in an empty church. One archpriest said to me: ‘No matter when I pass by your church, the bells are always ringing. Once I went in–nobody. Nothing will come of it. You’re ringing in vain.” But Fr. Alexey steadfastly continued serving–and the people began to come, many people. He would tell this story when asked how to establish a parish. The answer was always the same: “Pray.”

Eventually, his parish would be bursting, and long lines of people would stretch down Maroseyka Street, with spiritually hungry people seeking a crust of divine bread from the batiushka (little father). God granted Father Alexei a gift of clairvoyance, allowing him to read the hearts of those who came to him for guidance. He developed the reputation of a staretz (great spiritual elder). He managed the difficult trick of being strictly Orthodox in his knowledge, but making the faith accessible to all people. From the biography:

Many people, particularly intellectuals, had difficulty understanding and accepting Fr. Alexey’s approach because, quite simply, they didn’t understand the essence of Christianity. This is well illustrated by the case of Vladimir S.:

“I became acquainted with Batiushka soon after the February Revolution of 1917. I remember that when I

St. Alexei Mechev of Moscow

first went to the church on Maroseyka, there was a lot there that bothered me. It was, in fact, a real conflict between the mind and the heart, between adherence to the law on the one hand, and a profound love–covering and fulfilling the law–on the other hand … I was bothered because my love for God was weak, because I saw religion simply as a path towards satisfying a thirsty and curious intellect. I liked the strict, well-ordered and harmonious system of dogmas, I delighted in the beauty and universal conformity of the ecclesiastical rites. I believed in God, I was devoted to the Church, but I had little love for the Lord. And this cold, rational attitude towards religion subsequently ruined me, and even led me to leave Batiushka …

“When I came to Maroseyka … I saw the following: a priest of small stature, with a lined face and tangled beard, was serving together with an old deacon. The priest wore a faded, violet kamilavka [clerical hat]; he served somehow hurriedly and, it seemed, carelessly: he was forever coming out of the altar to give confession at the cliros [part of the church reserved for the choir]; sometimes he talked or searched for someone with his eyes; he himself carried out and distributed the prosphora [blessed bread, but not Holy Communion].

“All this–and especially the confession during Liturgy–had an irritating effect on me. And the fact that a woman read the Epistle, and that there were too many communicants, and the uncalled-for Blessing of the Water [after Liturgy] … None of this agreed with my conviction that conformity in church rites was absolutely essential. /…/

“[But gradually] I became involuntarily attached to Maroseyka; I became accustomed to the church services, and their deviations from the Typicon [book of church services] no longer bothered me. On the contrary, nowhere could I pray so fervently as at Maroseyka. Here one sensed that the walls were permeated by prayer, one sensed a contagious prayerful atmosphere which one didn’t find in other churches. Some people, whether by tradition or out of desire to hear a deacon and choir, go to wealthy and renowned churches; here people came for one reason alone–to pray …

“It happened that one would come to Father Alexey with some complex dogmatic problem. He would say with a smile: ‘Why are you asking me; I’m an ignoramus’ … ‘You’re forever wanting to live through your mind; you should try to live as I do–through the heart.’ This ‘life through the heart’ explained many of the deviations in church service which Batiushka permitted. When reason said that it was necessary to observe the prescriptions of the Typicon–not to confess during Liturgy, not to take out prosphora after the Cherubic Hymn, not to communicate late-comers at the north door after Liturgy, etc., etc.–Batiushka’s heart, burning and overflowing with love, caused him to disregard reason.

‘How can I possibly refuse someone confession,’ he would say. ‘Perhaps this confession is the person’s last hope, perhaps by turning him away I may cause the ruin of his soul. Christ didn’t refuse anyone. He said to everyone: “Come unto Me …” You say, What about the law? But where there is no love, the law does not work unto salvation; true love, however, is the fulfillment of the law (Rom. 13:8-10).'”

Vladimir’s comments may leave the impression that Fr. Alexey didn’t particularly care or wasn’t well-versed in the Church service rules. This isn’t true:

“A first-rate expert on the Typicon and the services, he noticed everything, saw everything, all the mistakes and omissions in the service, especially with those young people with whom he served in his latter years (and he loved serving with them). But he left the impression that he saw nothing, noticed nothing. After some time had passed, at a convenient and appropriate moment, he’d bring up the matter and correct it. The more glaring errors–or the ones which had some bearing on the service–he’d correct himself in a manner so discreet that it passed unnoticed by the server who had erred, much less by the congregation: he himself would start to sing in the proper manner, or would do something that someone else was supposed to have done. This is a very rare quality among the clergy.”

Notice that Father Alexei did not negate the forms of Orthodoxy, but he bent them to conform to the essence of Christianity, and to save souls. I think there is an important distinction to be made here between St. Alexei’s approach, and that of Pope Francis. As far as I can tell, Pope Francis really is changing the substance of magisterial Catholicism, but he’s doing so under the veil of mercy. That’s not what St. Alexei was doing with Orthodoxy.

Nevertheless, when I read this story about the rigid parishioner Vladimir, and St. Alexei’s counsel to him, I see tendencies in myself from my Catholic days, tendencies which still remain with me to a certain extent as an Orthodox. (‘You’re forever wanting to live through your mind; you should try to live as I do–through the heart.’) I am sure that I will have to do combat with this tendency within myself for the rest of my life. And for my conservative Catholic brothers and sisters, maybe the trial that is Pope Francis is a call to repentance in the same way St. Alexei called to Vladimir. To be clear, I don’t for one second buy Francis’s steady rebukes of anybody to the right of himself as “rigid.” Far too often these accusations are hurled by people, including clergy, who wish to overthrow orthodoxy in the name of mercy.

Nevertheless, I think it is worth all of us who are more or less on the theological and moral right within our own confessions to consider whether or not there is merit in these accusations. We are often so eager to defend orthodoxies against modernists that we fail to recognize that our critics might have something of a point.

Anyway, let’s end with Douthat’s prescription to his fellow conservative Catholics: to wait. Think of the little Batiushka of Maroseyka Street, saying the liturgy all alone in his tiny church (which I visited) for nine years, keeping the faith with no assurance that the people would come. And come they eventually did! Think of all the souls saved because of Father Alexei’s quiet, unseen fidelity. Father Alexei did not save the world. In fact, as I’ve said above, his son, who took over the parish after he passed in 1923, presided over the closure of the parish by the Bolsheviks, and his own martyrdom. And yet, the Church remembers them today as saints in glory. In the eyes of God, they succeeded.

Only in Christianity is defeat possible to be reified as success. But it’s true. Ours is a paradoxical religion.

Reading Douthat’s interview with Cardinal Burke, and his analysis of it, I find it impossible to reconcile what conservative Catholics profess to believe about the papacy, certainly since the first Vatican Council, with sustained opposition to Pope Francis. But like I said, Christianity is a religion of paradox. Some traditional Catholics, having concluded that they were mistaken about the papacy, will find their way into Orthodoxy. If this is you, welcome — but be aware that you are coming into a Church with its own problems, and that you will need to commit yourself not one bit less to personal holiness, and all it entails.

I suspect that most conservative and traditional Catholics, at least for the foreseeable future, will do as Douthat prescribes, and wait to see what God does with their church. I think now of my conservative Catholic friend, a former culture warrior within the Catholic Church, who is now overwhelmed by the messes Francis has made. As I wrote, he is now devoting himself to trying to build up the parish where he worships. There is deep wisdom in that, and not just for faithful Catholics.

Icon of St. Alexei Mechev (left) and his son St. Sergei Mechev, with the church on Maroseyka Street between them

Icon of St. Alexei Mechev (left) and his son St. Sergei Mechev, with the church on Maroseyka Street between them

The post The Trial Of Conservative Catholicism appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 10, 2019

Harry Billinge: A Man In Full

A clip of the final minutes of this 11-minute Remembrance Day BBC interview with Harry Billinge, a 94-year-old D-Day veteran, has gone viral. The last two-and-a-half minutes are jaw-dropping, but the entire interview is deeply moving. Michael Brendan Dougherty tweeted, “The past is a different country, and he is its ambassador.” Very true. Here’s the whole thing. It’s like a spectral visitation from an eternal warrior. Harry Billinge speaks like a prophet. Try to get through it without tears.

The post Harry Billinge: A Man In Full appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 8, 2019

Two Russian Icons

I came across that painting above earlier this week in the Russian State Museum. It stopped me in my tracks. The reproduction above, from the museum’s website, can’t do justice to the canvas itself. It’s titled “The Mother Of God Of Tenderness Towards Evil Hearts.” The artist is Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, who painted it in 1915. It is said to be his response to the horrors of the First World War. It is related thematically to the traditional Russian icon of The Mother of God, Softener Of Evil Hearts.

I can’t really say why this particular image of the Virgin Mary is so moving to me. But it is. I brought back a print of it, and will have it framed.

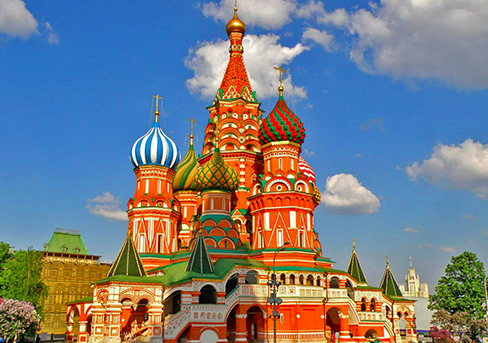

Another Russian icon — not literally an icon, but iconic — is St. Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square. This is the image most people associate with Russia, and rightly so. It’s one of the greatest buildings in the world. It’s every bit as breathtaking in real life as in photos:

It’s called St. Basil’s Cathedral, though its official name has to do with the Mother of God. Tsar Ivan the Terrible ordered it built to commemorate his victories in wars. St. Basil (Vasily) was a fool-for-Christ — that is, a very Russian figure who lives like a crazy person, but who is believed to do so to humiliate themselves, and in so doing serve God. Basil would walk the streets of 16th century Moscow nearly naked, in summer and winter. He preached mercy for the poor, and developed a reputation for rebuking Tsar Ivan (he was probably the only man in Russia who could get away with that). Once Basil threw some raw meat down at Ivan’s feet during Lent, telling him that given all the murders he had committed, it didn’t matter if he violated the Lenten fast by eating meat.

Can you imagine having the nerve to do that to Ivan the Terrible, who had even killed his own son? Holy food indeed.

Despite all that, when the holy fool Vasily died in 1557, Tsar Ivan was one of his pallbearers. He’s buried in the cathedral that by popular acclaim came to bear his name.

Russia is quite a country. Go, if you have the chance.

Advertisement

Liz Warren’s Trans Train Whistlestop

Thank you, @BlackWomxnFor! Black trans and cis women, gender-nonconforming, and nonbinary people are the backbone of our democracy and I don’t take this endorsement lightly. I’m committed to fighting alongside you for the big, structural change our country needs. https://t.co/KqWsVoRYMb

— Elizabeth Warren (@ewarren) November 7, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Well, that’s clarifying. “Backbone of our democracy.” That’s about what you would expect a Harvard faculty member to say. I’m old enough to remember when Democrats talked that way about folks like this:

via Walmart

Well, maybe they’re trans, and it’s okay for Liz to love them.

Advertisement

November 7, 2019

Reading Darkness At Noon

On the flight to Russia, I began reading Arthur Koestler’s 1940 anticommunist novel Darkness At Noon. I finished it on the flight from Helsinki to Miami (where I’m writing this, waiting for the connecting flight to New Orleans). Here are some initial thoughts (begging your pardon if this sounds fragmented; I’m pretty tired). Having read most of the novel on the flight back from Russia, where I met with people who survived the gulag, it made a tremendous impression on me.

For those who don’t know, Koestler was a Hungarian-born Jewish communist who became disillusioned by the Moscow Trials and the Stalinist Great Terror. Darkness At Noon was published shortly after the conclusion of the trials; Koestler more or less wrote it as current events. The protagonist, Rubashov, is a prominent Bolshevik who has fallen out of favor with Stalin, and who, at the book’s beginning, is arrested and imprisoned. The narrative takes place within the prison, as Rubashov faces interrogation that leads to his execution. His ultimate fate is never really in question; the drama lies in Rubashov’s reckoning with Marxism, the meaning of the Revolution, and his own responsibility for the charnel house that the communists had made of Russia.

The fates of two communist true believers who suffered for the Marxist faith loom large in Rubashov’s mind. Richard was a young German communist cell leader who had been persecuted by the Nazi regime, and whose pregnant wife, also a revolutionary, was in prison. A few years before his arrest, Rubashov went on an undercover mission to Germany to meet with Richard. He hears Richard’s story about how the Nazis have all but destroyed the local Communist Party, but none of that matters to Moscow. Rubashov is there to tell the desperate young man that he has been excommunicated from the Party for not strictly following Moscow’s directives in propaganda he distributed. It is clear that Richard is going to be killed when the Nazis catch him; the Party is leaving him to face them alone.

The second true believer was Little Loewy, an aging party stalwart who was a real proletarian. He labored among the longshoremen in a Belgian port, faithfully executing Moscow’s directives. He was beloved by the dock workers. Rubashov came to Belgium to order the dock workers to unload Soviet ships bringing supplies intended for Mussolini’s regime. When they balk, the Soviets expose the cell. Little Lowey hangs himself. This episode, like the one with Richard, is meant to show how the Soviet leadership had no problem throwing its most faithful workers to the wolves.

There is a third person whose fate weighs on Rubashov’s conscience: his secretary and lover, Arlova. She was arrested and executed for a trivial reason: keeping copies of the works of disfavored Bolsheviks in the office library, and not having enough copies of Stalin’s speeches. In the hearing where her fate was decided, Rubashov declined to defend her, protecting himself (temporarily, it turned out), but sealing her doom.

Most of the narrative consists of dialogues between two interrogators — first, Ivanov; then Gletkin — who are trying to get a confession out of Rubashov for a show trial. They want him to admit to conspiring to murder Stalin, and other counterrevolutionary acts. Of course he’s not guilty, but he’s going to be shot anyway. A confession from a Bolshevik as prominent as Rubashov will justify the Terror in the eyes of the Soviet public.

Why would a man confess to something he did not do? Torture could compel a confession, but Rubashov is not tortured (though the endless interrogation, under conditions of sleep deprivation, are harsh). Ivanov, an old friend and comrade, attempts to convince Rubashev to confess voluntarily. The gist of Ivanov’s efforts is to justify the sadism and mass murder of Bolshevism, and in turn to convince Rubashov that the last service he could do to the Party is to make this confession. (In fact, two leading old Bolsheviks, Zinoviev and Kamenev, made false confessions at their show trials; one of them, can’t remember which, addressed his children at the trial, telling them that whatever the Party decides what to do with him, it will be right, and exhorts them to stay loyal to Stalin.

Ivanov’s line is that anything that the Party does is justified because it is trying to bring about a better future for humanity. He says to Rubashov, “And we should shrink from sacrificing a few hundred thousand for the most promising experiment in history?”

More Ivanov:

There are only two conceptions of human ethics, and they are at opposite poles. One of them is Christian and humane, declares the individual to be sacrosanct, and asserts that the rules of arithmetic are not to be applied to human units. The other starts from the basic principle that a collective aim justifies all means, and not only allows, but demands, that the individual should in every way be subordinated and sacrificed to the community — which may dispose of it as an experimentation rabbit or a sacrificial lamb.

For the Bolsheviks, the individual was not sacred; the collective was. Social justice was something that was accomplished for classes. If achieving social justice required imprisoning and killing individuals who were guilty of nothing, then it was justified. To be sentimental about the fates of individuals was weakness.

Over the course of the novel, Rubashov comes to doubt his own commitment to the Marxist faith. It’s a metaphysical crisis for him. He loses confidence in philosophical materialism, and the power of human reason, because they deny the mystery and inviolable dignity of the individual human person. In his diary, Rubashov writes: “Geometry is the purest realization of human reason; but Euclid’s axioms cannot be proved. He who does not believe in them sees the whole building crash.”

As you know, I read the book as part of my research for the book I’m working on now. I want to understand communism better, so I can understand why emigres to the West from communist countries are sensing today a return of the kind of thinking characteristic of the Marxist dictatorships from which they fled.

Though the differences between the Soviets and our own Social Justice Warriors are obviously vast, Koestler’s novel helped me to understand something important to their own ideology and psychology, and why they are a threat that we can’t dismiss. This is why those who grew up under communism can identify this way of thinking, even as it remains hidden to us Americans who have no experience with it.

Generally, the SJWs are not doctrinaire Marxists, but they also conceive of justice as a matter of group relationships. If achieving Social Justice requires rolling over the rights of an individual, then the ends justify the means. This is why wherever the SJWs gain authority, they attack not only conservatives, but old-school liberals. Though I doubt very much that most of them have much idea of the role the concept of History plays in classical Marxist thought, they believe that they are indeed on the Right Side Of History, and that History will justify them.

When female high school athletes are robbed of the chance to excel in their sports because they are beaten by “girls” who are biologically male — this does not matter because this advances the cause of justice for transgenders. When college men stand accused of rape, they must be guilty, because achieving justice for women requires it. If men like James Damore offer opinions that contradict the ruling ideology at their companies or institutions, they must be thrown out as a counterrevolutionary. When a distinguished personage like Roger Scruton is sandbagged and lied about by a left-wing journalist, who publicly exults for having taken a conservative scalp — who cares, as long as the goal of punishing old white conservative males has been advanced. When a less qualified person is hired for a job over a more qualified person, because the less qualified employee is a member of a group entitled to Social Justice — well, too bad for the individual, who “should in every way be subordinated and sacrificed to the community.”

You know what I’m talking about. The rejection of the sacred worth of individuals-as-individuals (as distinct from members of a favored class or group), and the embrace of an ends-justifies-the-means ethic, is what the cult of Social Justice stands for. People who think like this dominate universities, the media, the Democratic Party, and corporate America. There is no Stalin of the Social Justice Warriors, but that in no way means they are not dangerous. As Solzhenitsyn wrote in The Gulag Archipelago, the liberal intellectuals of late 19th century Russia, who stood against Tsarist abuses, had known that in only a few short decades, the government that overthrew the Tsar would establish a tyranny incomparably more brutal and comprehensive, they would scarcely have believed it.

If we don’t stand up to this insanity now, we will greatly regret it in the years to come.

Advertisement

The Wonder Of Russia

Hello from the Helsinki Airport, where I’m waiting for my connecting flight back to the US. I’m looking out the window at now on the runways — the first snow-on-the-ground I’ve seen on this trip, thank goodness. My generous hosts Evgeni and Tanya Vodolazkin woke up me early this morning and got me into a cab, which began the long journey home. When I arrive in New Orleans (at the new terminal!) around midnight tonight, I will have been traveling for 24 hours. You can be very sure that I will be happy to be in my own bed, under the same roof with my family.

But oh, what a trip this has been. Yesterday, Tanya accompanied me to a store in St. Petersburg where I was able to buy specific presents I wanted to bring back for Julie and Nora. Nearby was the Dostoevsky Museum, which was the novelist’s final residence. In his study there he wrote The Brothers Karamazov. Alas, the museum was closed until 1 pm. I feared that I wouldn’t have enough time to see it and to spend meaningful time in the Russian State Museum off of Nevsky Prospekt, so I decided to visit Dostoevsky on my next trip to St. Petersburg.

I walked over to the Kupetz Eliseev food hall to buy some treats for Julie and the kids:

,

It was a total delight, just being in the store. I won’t say what I bought — Julie and my son Matthew read this blog — but I will say that for myself, I bought a kind of sweet preserve made from tender young pine cones in syrup. Never seen that before. Then to Starbucks for the wifi, and lunch at a Georgian place. I must have eaten at least five Georgian meals during my 10 days in Russia. For my last one, I ate khachapuri, Georgian cheese bread, with a raw egg on top. I am telling you a true fact, people: whoever figures out how to mainstream this stuff in America will become very rich. It is indescribably delicious. It uses melted sulguni cheese, which has the consistency of mozzarella, but is tangy. Some future trip of mine has to go to Tbilisi, where I can visit Orthodox churches and monasteries, and eat more Georgian cuisine. If you missed this Lauren Collins piece about Georgian food in the New Yorker earlier this year, oh boy, are you in for a treat. She writes, “Decades from now, you may recall 2019 as the year you first tried khachapuri.” Yes, indeed.

After lunch, I sauntered — no, actually, I plodded , in the boots I brought in case of snow — up Nevsky Prospekt to the turn for the State Russian Museum, dedicated to Russian art. Located in what was once the Mikhailovsky Palace, this museum was founded by Nicholas II. I had hoped to go to see Ilya Repin’s famous canvas, “Reply Of The Zaporozhian Cossacks.”

I have pasted in the painting below, but before you see it, read the message the Ottoman Sultan supposedly sent to the Zaporozhian Cossacks in 1676, and their reply:

Sultan Mehmed IV to the Zaporozhian Cossacks:

As the Sultan; son of Muhammad; brother of the sun and moon; grandson and viceroy of God; ruler of the kingdoms of Macedonia, Babylon, Jerusalem, Upper and Lower Egypt; emperor of emperors; sovereign of sovereigns; extraordinary knight, never defeated; steadfast guardian of the tomb of Jesus Christ; trustee chosen by God Himself; the hope and comfort of Muslims; confounder and great defender of Christians – I command you, the Zaporogian Cossacks, to submit to me voluntarily and without any resistance, and to desist from troubling me with your attacks.

–Turkish Sultan Mehmed IV

The Cossacks replied:

Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Turkish Sultan!

O sultan, Turkish devil and damned devil’s kith and kin, secretary to Lucifer himself. What the devil kind of knight are thou, that canst not slay a hedgehog with your naked arse? The devil shits, and your army eats. Thou shalt not, thou son of a whore, make subjects of Christian sons; we have no fear of your army, by land and by sea we will battle with thee, f*ck thy mother.

Thou Babylonian scullion, Macedonian wheelwright, brewer of Jerusalem, goat-f*cker of Alexandria, swineherd of Greater and Lesser Egypt, pig of Armenia, Podolian thief, catamite of Tartary, hangman of Kamyanets, and fool of all the world and underworld, an idiot before God, grandson of the Serpent, and the crick in our dick. Pig’s snout, mare’s arse, slaughterhouse cur, unchristened brow, screw thine own mother!

So the Zaporozhians declare, you lowlife. You won’t even be herding pigs for the Christians. Now we’ll conclude, for we don’t know the date and don’t own a calendar; the moon’s in the sky, the year with the Lord, the day’s the same over here as it is over there; for this kiss our arse!

Ilya Repin, “The Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks”

The canvas itself is huge, almost as big as a wall. It is a favorite of my son Matt, so I promised him I would go pay it homage for him. I would have gone to the Russian State Museum for that alone, but before I got to St. Petersburg, I visited the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and was deeply impressed by the Russian paintings on display there. So few of these painters are known in the US. I was moved by the intensity of their vision, and the tableaux they chose. Something told me that after the Hermitage, the Russian State Museum was the one to see in St. Petersburg.

This was the right choice. In fact, were it not for Rembrandt’s incomparable “Return of the Prodigal Son” at the Hermitage, I would say that I enjoyed the Russian State Museum even more. There was so much unfamiliar work to see! I took lots of photos, and will do a long post about it, featuring graphics, when I get back to the US. (I have been confounded in trying to get photos off my new camera.) I’ll just say here that the 19th and 20th century paintings at this museum are a revelation. When the Russians are painting in an Impressionistic style, as was the style of the late 19th century, they somehow bring a vibrancy to their canvases that one doesn’t see in European work (or, as is more likely, a Westerner’s eyes have become so accustomed to French Impressionism that it doesn’t impress as it once did, so to speak).

To me, the most thrilling paintings were the ones in the transition between Impressionism and Abstract Art — that is, the Symbolists, the Cubists, and the Futurists. I have never really cared for that kind of painting, and I’m not sure why, but these Russian works opened my eyes. I love that museum so very much. I am going to have to think about it, and what it says about the Russian character.

It turns out that there’s a big Ilya Repin exhibit on at the museum now. I was able to see many of his works. His realism is not really my thing, but there were some fantastic paintings. I can’t describe them well here (and besides, my plane will be boarding soon). I will show you in this space when I get home.

Please, St. Petersburg visitors, do not neglect to see the Russian State Museum! They even have several Andrei Rublev icons (though the most famous one, the Holy Trinity, is in the Tretyakov).

It was a long walk in the dark back to the Vodolazkins’ place in the Petrograd part of the city, but I savored it as much as I could. The Nevsky Prospekt ends at the Winter Palace. I walked slowly across the bridges across the two rivers that split the great Neva, stopping to survey the glorious panorama: the Winter Palace on my right, the Peter and Paul Fortress on my left. There can be no doubt that St. Petersburg is one of the world’s great cities.

Just before reaching their home, I ducked into a tiny bakery and bought two loves of Borodinsky bread, a dark rye sourdough. I haven’t tasted it yet, but Zhenya Vodolazkin recommended it as classically Russian, so I wanted to bring some home. Russian bread is incredibly inexpensive. I bought two small, gorgeous loaves for the equivalent of $1.25.

I want to say something about the Vodolazkins. I began an epistolary friendship with Evgeni four years ago, when I discovered his great novel Laurus, and began writing about it on this blog. A Confederacy of Dunces is my favorite comic novel; Laurus is my favorite serious novel. I had hoped someday to meet the author, and convey to him in some way how much his work has meant to me, and to many Americans, some of whom write me to tell me that they discovered Orthodoxy through its pages, or deepened their own commitment to Orthodox Christianity. When I planned to come to Russia to do research for my next book, I wrote to Zhenya and asked him if I could take Tanya and him to dinner when I was in town. He insisted that I stay with them. Who could pass up an offer like that?

The Vodolazkins’ apartment is exactly what you would expect from two Russian scholars to live in (Tanya also works at Pushkin House; her specialty is hagiography). There are books everywhere in the house, and art on the shelves and the wall. The apartment is intimate and cozy. I cannot overstate how kind and hospitable the Vodolazkins were to me. They passionately love Russia, but they also love Americans, and spoke of how they hope for greater friendship between our countries. I asked them about their visit to New York City a couple of years ago, which was their first to the US. They loved it, and could not get over how friendly Americans were.

“We need to learn from you,” Zhenya said. “Russians walk around with closed, dark faces. Americans are so open.”

When I told him that in the US, New Yorkers have a reputation (undeserved, I think) for being the most rude to strangers, Zhenya found that hard to believe. “Just come to Louisiana and see how we Southerners treat our guests,” I said. And I hope both of them do.

Sitting at their kitchen table, eating borscht and drinking vodka was one of the great memories of my trip to Russia. These two are so gentle, and so devoted to their work, and to each other. And, of course, to God: we stood at the table before every meal, facing the icon over the kitchen door, and prayed for the Lord’s blessing, in the Orthodox style.

The plane will be boarding shortly, so I will need to end this. I’m sure I’ll be writing more about Russia when I’m back home, but allow me to say right now how much this time spent among Russians meant to me. They are a great people, a passionate people, a difficult people, and a people gravely wounded by tragedy and suffering. I want to know more about them, much more. I found that in the Russian museum, what I loved most were the photographs of the burly Slavic boyars and knights; I prefer them to the Enlightenment Neoclassicism of Peter the Great. I intuit that what is wild and coarse in the Russian tradition is the source of its greatness. When I finish my research for my book, I am going to return to James Billington’s The Icon And The Axe, and finally finish it, over 30 years after it was assigned to me in high school (I still have my old copy). The Russian people are so mysterious to me, even more so now that I have been here. More mysterious, but also much more dear.

Thank you, Vodolazkins, and thanks to everyone I met in Russia, and who was so kind and welcoming to this American stranger. I will be back.

(Readers, if you haven’t yet read Laurus, I hope you will. And if you have read Laurus, check out The Aviator, Vodolazkin’s follow-up. Though set in the 20th century, not in medieval Russia, as Laurus is, it too is wonderful, though I don’t know if anything can top Laurus in my estimation.)

Advertisement

November 6, 2019

Q: How Do You Freak Out A Russian?

Good afternoon from a Starbucks on Nevsky Prospect. I’m on my way to the Russian State Museum, but ducked in here for caffeine and wifi.

I leave for home tomorrow, and believe me, there will be a lot of Russia-oriented blogging. I don’t want to waste my last day here on the Internet. I did see the election results from Virginia and Kentucky; that left me feeling gloomy about the 2020 election. Virginia I understand, but Kentucky — man, that’s a blow. I’m sure the usual suspects will say that the election results there are fake news, and that a Republican in a red state did not lose the governor’s race, and that I’m a tool of the Deep State for having noticed it.

While my hosts are at work, I’ve been exploring the city. Sometimes I run into Russians who speak English. They are always friendly and eager to talk. One thing that really stands out is how uncomprehending they are when we start talking about political correctness in the US, especially around LGBT issues. Even Russians who tell me they are not fans of Putin find the illiberalism of the American left, especially on LGBT topics, utterly mystifying.

One man told me a story about a friend in Paris who owns a bookstore. The bookstore owner was quoted publicly saying that it’s wrong to propagandize children with LGBT storybooks. Because of that, the intelligentsia condemned the man as a bigot, and his business suffered.

I told my Russian interlocutor that this is easy to believe, that this kind of thing happens in the US too. I found with this man the same kind of experience I have had every time this kind of thing comes up in conversation with Russians: they struggle mightily to comprehend that America, of all places, has become this sort of place. It shocks them that our public square has become so illiberal, because of the political policing of the left, but more than that, they find my stories about the relentless propaganda by the media, academia, and the cultural establishment on behalf of Pride, and in particular the campaign to change the consciousness of children regarding gender theory — well, they find this offensive and incomprehensible.

One man told me, “I think people should leave gay people alone. What they do is their business, not mine. Those who chase them and beat them are wrong, and should be stopped. But how can they do this to children? Why do you Americans allow this? We have a law in Russia forbidding LGBT propaganda to children. I think almost every Russian supports this.”

And they’re right. It really is instructive to step outside of the Western cultural sphere and see our own country, and what has become normal. Even American conservatives like me are becoming numb to it, because it is everywhere, and ever-present. Look, Russia has plenty of problems, and I don’t want to hold it up as any kind of ideal society. In some important ways, I would probably count as a liberal if I lived in Russia. But I’ve gotta tell you, there is nothing quite like trying to explain Drag Queen Story Hour to a Russian to make an American realize how far gone his own culture is.