Rod Dreher's Blog, page 187

December 12, 2019

Church Without Community

A reader writes (and I post with his permission):

I’ve been reading your blog for two years, and I wanted to share something with you that I don’t think I’ve heard you touch on before.

I am an Evangelical Christian attending a church associated with the SBC. I am also a student at a conservative Evangelical seminary and have been a part of the Evangelical sub-culture my entire life, attending a Christian school since 5th grade and an Evangelical liberal arts college for my undergrad. I have been a part of many different churches over the years, and experienced many different forms of Christian community. I also served as a missionary for a year in Africa. This is my world, and I have never felt “disillusioned” with it until recently. What has prompted this? The fact that I’m not really BenOp-ing with any Christians in my life right now – but I am BenOp-ing (in a way) with my non-Christian coworkers.

I am a 29-year-old male. As I’ve been pursuing my degree, I’ve been working at a local coffee shop to pay the bills. In the 3.5 years since I’ve been working there, I have formed very strong friendships with my coworkers. My manager is also a Christian, and she and I and her husband go to the same church. There are two, maybe three other Christians who work there, out of a staff of over 20 people. But the rest are very much not Christians. Some (a large amount) were raised Catholic, but only one of them would still claim to have a form of faith. Most are your typical secular Millenials/Zoomers. They almost all fully embrace woke ideology and left-wing politics. They have minimal knowledge of the Bible. They are all in on feminism (most are female) and regularly espouse anti-male sentiments. Many are really into astrology/tarot and some other vaguely witchy things. Most live with their SOs. Most use drugs. Some go to abortion marches or other leftist protests. None go to church. None have for a very long time. Some believe in God, or some higher power, but most have a negative view of Christianity as an oppressive, patriarchal, bigoted religion.

And yet. These people feel more like family to me than most people at my own church. We have formed a thriving little community of solidarity and support at our store. We are in and out of each other’s homes. We help each other move. We watch each other’s pets when we go out of town. We hang out outside of work, have movies nights, go to the gym together, go to bars, have seasonal parties. We have a very active group text. We go to each other’s concerts (many are musicians). We avoid most of the gossipy, clique-ish crap and serial drama that plagues many workplaces. (I am also able to be completely open about my faith. I have shared my beliefs, even controversial ones, with many of my coworkers, and though we’ve had some civil arguments, it has never gotten ugly. Most respond with curiosity, and some have expressed interest in coming to church. So it’s a “mission field,” too.) Bottom line, I very often look forward to going into work more than I look forward to going to church or small group.

My church is great in so many ways. The preaching is wonderful, very Biblical and pastoral. And there are a handful of people there with whom I do sometimes spend time outside of church. The worship is rich and beautiful. But I am not “doing life” with these people. Part of this is geographical and socio-economic. Most of the people in my church live in the richer suburbs about 30-mins away from me. I live in a more urban neighborhood. Most are wealthy, attractive, Instagrammable couples with kids. I am single and, like I said, I work at a coffee shop…

But I think the biggest reason I don’t feel very connected to my fellow church members is because we just don’t see each other that often. I am at church every Sunday. I serve in the children’s ministry. I attend my small group most weeks. But this amount of regular exposure to the same people, which has been going on for over two years, hasn’t provided the same form of deep community that I have with my non-Christian coworkers. I spend time with my coworkers several hours each week. And because of the nature of the work, there is plenty of downtime to talk and laugh and form genuine friendships. It helps, too, that we are almost all in our 20s and 30s, and none of us have kids.

I am not alone in being bothered by this disparity between the “thickness” of community with my pagan coworkers and the sporadic, cursory nature of much of my church community. Like I said, my manager is also a Christian and goes to the same church as me. She and her husband, some of my best friends, are also my neighbors, and they feel the lack of connection with our church as well. We’ve begun discussing ways to remedy this situation. We don’t want to be those young people who just sit around and complain that none of the older people in the church ever “pursue” them. We want to take tangible steps to build stronger community. We’ve even discussed trying to form some sort of church plant in our neighborhood, because there are several other households of fellow church members (all singles, except for one married couple with kids) within five minutes of us.

But even if we did that, there’s a part of me that feels like there’s nothing short of actual communal living that would really feel “right.” (Visions of the Bruderhof dance through my head.) I am probably spoiled, because I have experienced several forms of deep, semi-communal Christian community in the past. The hall I lived on at my Christian college was extremely tight-knit, and basically had a “liturgical year” of events and traditions around which our hall life was structured. We worshiped together, ate every meal together, worked together, played together, and invested in one another daily for the entirety of the school year. I lived on that hall for all four years. When I lived in Africa I was a part of a missionary team that did most things together. Our homes had open doors and we lived near to one another. I was family to the team’s four Christian couples and their kids for a whole year. It was such a sweet time.

Will I ever have anything like that again this side of heaven? What I have with my coworkers is close, except it’s not a Christian community. For all the joy work friends bring me, I also feel weary and spiritually malnourished at times, and fear some of my Christian convictions and behaviors may be eroding. I wonder if this is a unique dilemma. It certainly goes against the narrative that our culture is always and only hostile to traditional orthodox Christians (though I do think that narrative is true on a national scale). Modern Americans are lonely and starved for community. They’re going to take it where they can get it. And if the church isn’t providing that community, something else will.

Is there anyone else out there who feels dissatisfied with church community and more connected to some non-Christian one? If so, what is to be done? Am I being formed and discipled by my work community into something other than Christ-likeness? How sustainable is this? What of those with weaker convictions than I? Will they be able to keep the faith if their non-Christian friends are more dear to them than their church family? If we aren’t actually living life together, then how can we ever fulfill the vision of the church in Acts 2 and 4? These questions and others keep me up at night. I thought I’d share in case you had any insights.

What a fantastic letter. Let’s talk about it, readers.

The post Church Without Community appeared first on The American Conservative.

December 11, 2019

The Climate Crisis & The Benedict Option

Here’s a really thoughtful essay in The New Atlantis, titled “Beyond Climate Despair.” The author is Matt Frost. His argument is that “catastrophism” about climate change has failed to move the world’s population to make the radical changes necessary to avert the calamities ahead. Here’s his provocative thesis, in sum:

But we are not condemned to a choice between despair and denial. Instead, we must prepare for a future in which we have temporarily failed to arrest climate change — while ensuring that human civilization stubbornly persists, and thrives. Rather than prescribing global austerity, reducing our energy usage and thereby limiting our options for adaptation, we should pursue energy abundance. Only in a high-energy future can we hope eventually to reduce the atmosphere’s carbon, through sequestration and by gradually replacing fossil fuels with low-carbon alternatives.

It is time to acknowledge that catastrophism has failed to bring about the global political breakthrough the climate establishment dreams of, and will not succeed in time to avert serious warming. Instead of despairing over a forever-deferred dream of austerity, our resources would be better spent now on investing in potential technological breakthroughs to reduce atmospheric carbon, and our political imagination better put toward preparing for a future of ever more abundant energy.

Frost cites a poll showing that most Americans, by a huge margin, believe that climate change is happening … but also very few believe that we can or will do anything to stop it.

The bleak poll results may reflect a broad, if perhaps tacit, agreement that we have reached diminishing returns on dread. Even now that most Americans accept the dire predictions of scientists and journalists, their assent does not change the fact that we currently lack the institutional, technological, and moral resources to prevent further climate change in the near term. The lay public has been taught to regard stabilizing the climate as an all-or-nothing struggle against the encroachment of a dismal future, and the bar for success is set high enough that failure is now the rational expectation.

The people who keep insisting, hysterically, that humankind can solve the climate change crisis if only we put our minds to it are thinking magically. It’s not that it absolutely, positively cannot be done. It could be done if all the world’s industrial economies collapsed utterly overnight. But we all know that that is not going to happen, nor, given the inconceivable human death and suffering that would occur in that instance, should we want it to happen. If you think that any nation will voluntarily send itself back to pre-industrial existence for the sake of what feels like an abstraction, you’re deluded. Any national leader who proposed that seriously would face rioting in the street. Macron tried to add a gas tax, and got the Yellow Vests movement. Here’s the core of Frost’s contention:

This combination of brooding pessimism and delusional optimism has not only failed, it has left us poorly equipped to imagine alternative responses.

Such as? Frost has some really interesting suggestions. That section begins like this:

We will not stop global warming, at least in our lifetimes. This realization forces us to ask instead what would count as limiting warming enough to sustain our lives and our civilization through the disruption. There can be no single global answer to this question: Our ability to predict climate effects will always be limited, and what will count as acceptable warming to a Norwegian farmer enjoying a longer growing season will always be irreconcilable with that of a Miami resident fighting the sea to save his home. But because our leadership has approached climate change as a problem of coordinated global action, they have constructed quantitative waypoints around which to organize the debate.

Read it all.It’s the most constructive, realistic thing I’ve seen on the climate change problem in ages. I leave it to you readers who follow the climate change issue more closely, and/or who have a scientific or economic background, to comment on those aspects of Frost’s story. As I read it, I kept reflecting on how Frost’s insights into how to cope with the unstoppable climate change crisis might affect our thinking about the Benedict Option and the decline of Christianity.

Consider this rewrite of the paragraph above:

We will not stop the steep decline of Christianity, at least in our lifetimes. This realization forces us to ask instead what would count as limiting its decline enough to sustain our individual and collective faith through the disruption. There can be no single global answer to this question: Our ability to predict religious life will always be limited, and what will count as a sustainable degree of Christian practice to Norwegians living in a stable, prosperous, homogeneous secular society will always be irreconcilable with that of a Nigerian fighting militant Islam and the encroachment of secular hedonism from the West via the Internet. But because our leadership has either denied, in one of various ways, that that Christianity has entered into an advanced and likely irreversible state of decadence, or has approached it as something we can only face by waiting for Jesus to take the faithful to heaven in a teleportation extinction event called the Rapture, they have failed to establish constructive points around which to organize the debate — or even to have a debate at all.

Of course if you have read The Benedict Option, you will know that that is precisely the point of the book: first, to convince Christian readers that this is not merely a cyclical downturn in Christianity, but quite possibly the beginning of its end, at least in the West; and second, to suggest practical ways we can start responding to a crisis more severe than any since the collapse of Western Roman civilization in the fifth century.

The most basic difference between our time and then is that the West had not yet been Christian. Most of western Europe had not yet been evangelized, or more than lightly converted. And the entire mental and social framework of people then was very, very different from what we have today, in late modernity — a period that arrives after the West has been entirely Christian for at least a thousand years.

If we only brood pessimistically about Decline and Fall — this is my personal temptation — we will be paralyzed, and not arise and take actions that stand to make this catastrophe endurable and survivable. But delusional optimism — “there is no problem,” or “actually, God is doing a new and wonderful thing with the church,” or “things will turn around sooner or later if we just sit quietly and wait” — is a death sentence.

Frost, in writing about the climate crisis, acknowledges that the problem is simply not one that can be solved by democratic societies. I encourage you to read his analysis; I’m not going to post so much of his (long) essay that you don’t go to it and grapple with its details. Let’s just say that he’s very persuasive on this point. Frost spends some time dealing with mistake of approaching the subject from the highly moralistic catastrophism that has characterized the way activists (hello, Greta!), journalists, and other engaged parties have favored.

In fact, Frost’s piece has helped me to understand better the most frustrating thing (to me) about this entire Benedict Option discussion: why so many anti-Ben Op people, despite my frequent and elaborately detailed denials, insist that the Ben Op is about heading to the hills to build bunkers and await the End. It’s like there is something compulsive deep inside people that makes them want to believe that extreme view, so they can dismiss the entire project.

Here’s what I’m getting at. Adapting Frost’s stance to the current crisis of the Christian religion, if Benedict Option Christians ran around saying at the top of their lungs that if all Christians don’t withdraw radically from the modern world by 2030, the faith will irreversibly collapse, most people would tune them out. Even if these prophetic Christians had facts and logic on their side, it would be realistically impossible to convince believers to take such an unimaginably extreme step. What if the prophets doubled down on excoriating the faithful for their unwillingness to embrace this kind of severe austerity? History does not give us reason to hope that masses of people respond favorably to this kind of thing.

But think about how climate activists and sympathetic journalists respond to anything other than maximally freaking out: they denounce them as timid half-measures. And climate-change deniers respond in kind, with charges of hypocrisy, e.g., “If these people really believed that a climate apocalypse was coming, then they would stop using air conditioning, stop flying in planes, and stop driving cars.” These snarky deniers aren’t entirely wrong. It is amusing to observe the vast distance between what climate activists say, and how most of them live. But the snarky deniers aren’t entirely right, either. Scientific facts don’t change based on whether or not people are hypocrites. Frost points to how the excessive moralization of the climate issue makes it hard to think clearly about what things we can do to get through the hard times ahead of us more bearable.

Well, I don’t see many Christians running around saying that we have to head to the hills and live like Bible-thumping survivalists. I don’t say that anywhere in my book, because I don’t believe it. I do believe, though, that Christians who don’t want to have to face the difficult truths about our situation invent a straw man version of the Ben Op to justify their own unwillingness to deal with this pressing crisis. If they can convince themselves that Benedict Option advocates are nothing more than Greta Thunbergesque malcontents, then (in their thinking) there must not be anything to worry about.

To be fair, it really might be the case that the only sensible thing for Christians to do is some version of “head for the hills”! I can’t afford to let myself think that, though, because there is no way that more than a relative handful of Christians would do such a thing, and, more importantly, there is no way that they could do such a thing. Most of us are far too enmeshed in the ordinary things of the world — jobs, families, houses, friends, responsibilities, etc. — to pick up and relocate to a Ben Op bunker. Nor do most people have the money for such a thing.

The forces driving climate change are understood, but unless we’re going to invent a time machine and go back to strangle the Industrial Revolution in its cradle, they are not going to be turned back in our lifetime. The forces dissolving Christian faith and practice go back even deeper into history than the Industrial Revolution — but, interestingly, the Industrial Revolution, and the radical social and economic changes it set into motion, has had as profound an impact on Christianity as on the global climate. Anyway, as with climate change, so with religious change: this is simply something we are going to have to ride out. We can’t even begin to figure out how to do that until and unless we give up the idea that the only choices available to us are to come up with a universal, complete solution to the crisis, or to deny that there is a crisis at all.

Frost writes:

This is not to suggest that because our politics have failed to arrest global warming we must somehow solve the problem outside politics, through voluntary commerce and innovation, while sovereign power recuses itself. On the contrary, our political efforts, domestic and international, must account for the lack of consensus, and should not presuppose sudden mass moral conversion or radical changes to our institutions. A successful politics for the era of overshoot will maintain continuity with our most enduringly human characteristics, appealing to our routine, unsophisticated self-interest as well as our loftier virtues. In the absence of a sweeping ethical revolution, a successful climate politics will look like a new variation on familiar methods, rather than a transformed social order.

That same paragraph, in a Ben Op context, would look something like this:

This is not to suggest that because our churches have failed to arrest Christianity’s decline we must somehow solve the problem outside the life of the institutional church, through individual religious efforts and innovation, while church leaders recuse themselves. On the contrary, our ecclesial efforts, domestic and international, must account for the lack of consensus, and should not presuppose sudden mass moral conversion or radical changes to our institutions. A successful religious strategy for the era of overshoot will maintain continuity with our most enduringly human characteristics, appealing to our routine, unsophisticated self-interest as well as our loftier virtues. In the absence of a sweeping ethical and spiritual revolution, a successful institutional Christian response will look like a new variation on familiar methods, rather than a transformed social order.

That is the Benedict Option.

There is another significant difference between solving the climate crisis and saving Christianity. If the climate crisis is going to be solved at some point in the future, it will be because science will have come up with a technology that can stop carbon emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere. In other words, this is a technical problem. There are no technical solutions to Christianity’s crisis. You can’t engineer away unbelief. But, in both cases, the solution will require something like a miracle — that is, the emergence of a phenomenon that we can’t imagine now, but that will actually exist, and will change everything. Our most realistic hope, then, is to engineer right now, working within the limits of our nature and our capabilities, ways to keep us alive (physically, in the case of the climate crisis, and spiritually in the case of the religious crisis) and thriving until that future miracle.

Once more, here’s a link to Matt Frost’s great piece in The New Atlantis. And, if these musings spark your curiosity, and make you reconsider your rejection of the Benedict Option, here’s a link to the book.

The post The Climate Crisis & The Benedict Option appeared first on The American Conservative.

Living — Not Just Performing — The Faith

I mentioned on Twitter the other day a conversation I overheard in which an older woman was telling her friend that she doesn’t understand her adult daughter’s relationship to her chosen religion. The daughter and her husband converted to Catholicism. Her mom asked if she goes to confession. The daughter told her mom no, that nobody in their parish goes to confession. The mom (not a Catholic) said to her friend, “I told her that if you’re going to be part of a religion, then really be a part of it.”

I thought of that just now when reading Tara Isabella Burton’s wonderful essay about how she got off the fence and started to think and live as an actual Christian, not just an aesthetic pretender. Excerpts:

Throughout my childhood, I kept an altar that was a fusion of Roman saints’ icons and Wiccan candles I purchased on the internet. I was a little bit Catholic, a little bit Episcopalian, a little bit Jewish, a little bit pagan. Then, in my late 20s, I discovered I was a Christian.

She learned that saying yes to Christ meant that she had to say no to many other things. More:

But for me, the most demanding part of embracing Christianity was sacrificing the safety of in-betweenness. I could no longer be a little bit pagan. Halloween parties that ironically-but-not-really celebrated witchcraft, say, or other staples of my at-times aggressively secular New York life were no longer simply curious parts of my spiritual eclecticism. I had to pick a side.

For the first time, I had to ask myself questions not just about what it all meant in an abstract way but what each decision—from posting on Instagram to choosing an outfit to drinking too much to hosting a party to committing to monogamy to planning a wedding—meant for me, as a Christian, in the framework of my Christianity. If God was real, if Christ really did come back from the dead, then nothing else mattered except insofar as it reflected that one hideous, impossible truth.

I had a similar realization — literally, a come-to-Jesus moment — in my twenties too. It was about sex. I finally quit lying to myself, and trying to convince myself that I could be fully Christian, except for that one area where I wanted to keep my options open. Not true. Either Jesus Christ is God, or he isn’t. If he is God, then that means he is the God of all my life, not just the parts I find easy to surrender to him. And despite what these liars (like the porn-supporting, lascivious Lutheran pastor Nadia Bolz-Weber in the present day) say, Christianity has never blessed sex outside of marriage. It’s just a lie — a lie that a lot of young Christians (as I was then) are prone to believe, but a lie all the same.

I had to want God more than I wanted myself, for once. Only then did my Christianity start to become real: when it cost me something valuable. I say “start” to become real, because a Christian’s life is one long, arduous journey to make the faith more real by dying to ourselves so that we become like Christ. If living the life of faith doesn’t hurt, ever, and if it’s nothing more than an amusing, pleasant bricolage, you’re not doing it right. And as TIB says in her piece, if it doesn’t make you an alien, a stranger to this world, you’re not getting it.

UPDATE: A reader highlights a longer essay in which TIB talks about how she came to the Christian faith in more detail.

The post Living — Not Just Performing — The Faith appeared first on The American Conservative.

Queering Children’s Imaginations

The New York Times is gonna New York Times, especially in the holiday season. Headline from its trans columnist Jennifer Finney Boylan’s latest:

Excerpt:

Prospector Yukon Cornelius’s sexuality doesn’t enter into the plot, of course. But in a scene that was deleted from the 1964 original, we learn that even though he claimed to be searching for silver or gold, in fact, Yukon C. was looking for a peppermint mine. No further questions, your honor.

They spoil everything, don’t they?

Why are you conservative Christians so obsessed about sex? they always whine. Meanwhile, The New York Times publishes op-ed columns like this that give the real game away. Likewise, this long BBC feature on a Los Angeles mom and dad who ran a secret gay porn empire, and who are in the piece treated like avant-garde cultural heroes. The problem is not that conservative Christians obsess about sex; the problem is that we don’t obsess on it (if we obsess at all) in the culturally correct ways. You can talk about it all the time if you want to, but you have to follow the progressive script.

Meanwhile, down in Texas, a mom is speaking out against the fact that a public school invited a drag queen to read stories to children there. Excerpt:

In fact, one school librarian at the center of the drag queen being invited to Blackshear Fine Arts Academy in Austin, TX to read to young children is an ALA librarian with the Texas Chapter of ALA ( aka Texas Library Association). She is not only an ALA librarian, but she holds two positions on the Texas Library Assocation’s LGBTQIA Round Table.

Texas Values obtained text messages between Blackshear Elementary School librarian, Roger Grape and the drag queen, Miss Kitty Litter. The text messages reveal that the school librarian was made aware of Miss Kitty’s dirty litter. Miss Kitty Litter was exposed earlier this year as having a criminal record for prostitution after the pro-family group, MassResistance, researched his involvement in drag queen story hours in the Austin Public Library. Texas Values published contents of the text messages found as a result of their Freedom of Information Act Requests.

From the Texas Values site:

In the documents released to Texas Values, it was discovered that David Richardson, a.k.a. ‘Miss Kitty Litter ATX’ texted Blackshear Elementary School librarian Roger Grape that he was concerned whether or not he would pass the school background check. ‘Miss Kitty Litter’ texted, “So the guidelines for submission automatically disqualify me if the deferred adjudication for prostitution is considered a conviction . . . so I don’t know if ethical to submit.”

Richardson, the drag queen, is referring to his arrest and conviction of a Class B Misdemeanor charge for Prostitution. According to emails sent to parents the reading event was scheduled to take place at 11 am and all readers had been screened by Austin ISD Partners in Education. However according to school records, Robinson a.k.a. ‘Miss Kitty Litter ATX’ was at Blackshear Elementary School for an extremely long period of time from 7:25 a.m. until 2:11 p.m. It remains unclear why Richardson required such an extended period of time at the school, and why he was allowed to pass the screening with a prior criminal conviction.

While dressed in drag, Richardson also failed to wear an identifying name tag as required by school policy. ‘Miss Kitty Litter ATX’ was allowed to read LGBTQ affirming books called “Julian is a Mermaid” and “Red: A Crayon’s Story” in the school library to 10-year-olds. A Blackshear Elementary School parent contacted the Principal prior to the event and voiced their disagreement with having a drag queen read to students, but the school did not cancel the event and instead separated the child from his classmates during the presentation.

So an elementary school librarian, gay activist Roger Grape, knowingly brought into the school to read to kids a gay drag performer once convicted of prostitution.

Miss Kitty Litter ATX (Source)

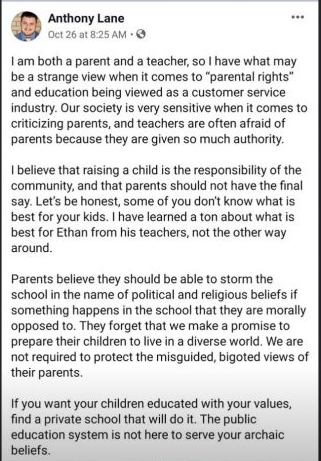

Miss Kitty Litter ATX (Source)Texas has had a problem in 2019 with this sort of thing. It seems that they can’t keep sex offenders and porn actors out of Drag Queen Story Hour. Noticing that, though, makes you a HATER. Any line you try to draw, even around little kids, is bigotry. Last month, in the controversy of the Willis ISD drag queen incident (separate from the Miss Kitty Litter thing, which happened in Austin), a teacher in that Texas public school commented:

Let’s be honest, some of you don’t know what is best for your kids.

Who is the “public” in public schools? Doesn’t the public have the right to fight back against LGBT activists turning classrooms into advocacy bully pulpits? Why are parents and others who object to their children being indoctrinated by these decadents considered crazy?

Just this morning, I was going over some notes from interviews with dissidents under communism. One of them advised that it’s important for dissidents to find each other and work together. He said that the enemy will try to isolate individuals and make them think they are insane, or at least far outliers.

I’d say that’s true in these cases. A public school teacher who says that “some of you don’t know what is best for your kids” absolutely does not have the best interests of your family at heart.

As with the trans columnist who pens a Christmas column exposing the secret queer code in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, people in this movement, including their allies within institutions, are constantly thinking about how to advance the cultural revolution. If you think you can ignore it, and that this will be a passing fad, or Drag Queen Story Hour is nothing to worry about, you’re lying to yourself. These progressive culture warriors, whose number in Texas this year includes a convicted male prostitute and child sex offenders, are counting on you not to fight back.

UPDATE: Er, wow. In an English classroom, six-year-olds are required, as an exercise of their imaginations, to write a letter telling a servant in a fairy tale why he should marry the prince. The teacher explains that the purpose of this kind of thing is to conquer the children’s minds to short-circuit prejudice:

The post Queering Children’s Imaginations appeared first on The American Conservative.

Francis The Pocket-Picking Pope

A conservative Catholic friend passed along to me this article from today’s Wall Street Journal (paywalled), with a salty line stating — I’ll put this nicely — that this is why he and his wife give nothing to these, um, dissembling churchmen. Excerpts from the piece:

Every year, Catholics around the world donate tens of millions of dollars to the pope. Bishops exhort the faithful to support the weak and suffering through the pope’s main charitable appeal, called Peter’s Pence.

What the church doesn’t advertise is that most of that collection, worth more than more than €50 million ($55 million) annually, goes toward plugging the hole in the Vatican’s own administrative budget, while as little as 10% is spent on charitable works, according to people familiar with the funds.

The little-publicized breakdown of how the Holy See spends Peter’s Pence, known only among senior Vatican officials, is raising concern among some Catholic Church leaders that the faithful are being misled about the use of their donations, which could further hurt the credibility of the Vatican’s financial management under Pope Francis.

Can you imagine donating to a charity that only spends ten cents of every dollar on actual charity? Who would do that? The Pope is not breaking any laws by doing this — he has a right to spend the donations as he likes — but this is not what the Church tells Catholics it is doing with the donations:

The use of Peter’s Pence donations mostly to plug the budget deficit is particularly sensitive for Pope Francis, who began his pontificate by calling for a “poor church for the poor,” and has continually emphasized the church’s mission to care for and advocate on behalf of the most vulnerable.

The head of the Vatican’s press office didn’t respond to a request for comment on the use of the funds.

Peter’s Pence, a special collection from Catholics around the world every June, is billed as a fundraising effort for the needy. The Vatican’s website for the collection, www.peterspence.va, describes it as a “gesture of charity, a way of supporting the activity of the Pope and the universal Church in favoring especially the poorest and Churches in difficulty. It is also an invitation to pay attention and be near to new forms of poverty and fragility.”

When asked about it last month, Francis defended this apparent sleight of hand:

“When the money from Peter’s Pence arrives, what do I do? I put it in a drawer? No. This is bad administration. I try to make an investment and when I need to give, when there is a need, throughout the year, the money is taken and that capital does not devalue, it stays the same or it increases a bit,” the pope said last month.

The Journal reporter, Francis X. Rocca, says that “no more of a quarter” of the Peter’s Pence donations are available for investments, because most of the money goes to run the Vatican and to keep its personnel living in the manner to which they have become accustomed.

Obviously the Vatican cannot run on prayers alone, and there is nothing wrong with the Pope asking the faithful to donate for the sake of its operational costs. But that’s not what they thought they were giving to with Peter’s Pence. They were told that these funds were all going to help the needy. Some people are more needy than others, it seems.

Ed Condon at the independent Catholic News Agency has been doing great work this fall exposing details of the Vatican’s financial shenanigans in relation to bad real estate deals originating in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State (which also oversees Peter’s Pence). For example, this from the other day:

A fund in which the Vatican’s Secretariat of State has invested tens of millions of euros has links to two Swiss banks investigated or implicated in bribery and money laundering scandals involving more than one billion dollars. The fund is under investigation by Vatican authorities.

The fund, Centurion Global Fund, made headlines this week that it used the Vatican assets under its management to invest in Hollywood films, real estate, and utilities, including investments in movies like “Men in Black International” and the Elton John biopic “Rocketman.”

Italian newspaper Corriere della Serra reported that the Centurion Global Fund has raised around 70 million euro in cash, and that the Holy See’s Secretariat of State is the source of at least two-thirds of the fund’s assets. The Vatican’s investment is reported to include funds from the Peter’s Pence collection, intended to support charitable works and the ministry of the Vatican Curia.

So, money that Catholics from around the world give yearly to support charitable work close to the heart of the Pope have actually been financing a biographical movies about rock star and gay rights crusader Elton John.

I think it’s gonna be a long, long time before a lot of Catholics give any more pence to the current Peter.

The post Francis The Pocket-Picking Pope appeared first on The American Conservative.

Porn Is Demonic, Says Top Occultist

I have been following the recent series of articles from social and religious conservatives arguing for the US Government to take concrete steps to fight the pornography epidemic. Here are good pieces from C.C. Pecknold (“Governments can and must taken on the billion-dollar pornography industry”), Sohrab Ahmari (“Porn isn’t free speech — on the web, or anywhere”), and Matthew Schmitz, whose Washington Post essay, “The Case For Banning Pornography,” starts like this:

It is time to ban pornography.

Nothing can shock us except this suggestion. We find it perfectly acceptable that smut, no matter how bestial or misogynistic, should be widely available. We even think it a moral imperative, a dictate of freedom. It does not trouble us that children can view acts of rape, real or simulated, with a click of a mouse, but if someone proposes that we prevent them from doing so, dirty old Uncle Sam begins to shudder. Respected citizens stand up to object. Gallant young civil libertarians come riding into town, ready to defend the imperiled modesty of Lady Liberty.

“Ban” strikes us as a nasty word, conjuring up memories of McCarthyism, the Spanish Inquisition and the third-grade teacher who washed your mouth out with soap. We tell ourselves that bans are never really effective, that it is too hard to distinguish between what should be banned and what shouldn’t. Above all, we know that bans are blunt instruments, and believe that we are too sophisticated to employ such crude tools.

But are bans really so terrifying and impossible?

We are not averse to banning something when we think it is really wrong. We are happy to “ban” murder, rape and even certain types of speech (try yelling “Fire!” in a theater). We do not hesitate over the fact that there will be marginal cases, or that the banned activity will not magically be brought to an end. Our tolerant reaction to pornography stems less from a principled commitment to free speech than from a belief that porn isn’t so bad after all. Shouldn’t we be “sex-positive”? Who doesn’t need a little release?

This casual attitude would be impossible if we cared as much about misogyny as we say we do. Gail Dines, a feminist scholar who has succeeded Andrea Dworkin as the leading voice against pornography, has found that “the most popular acts depicted in internet porn include vaginal, oral and anal penetration by three or more men at the same time; double anal; double vaginal; a female gagging from having a penis thrust into her throat; and ejaculation in a woman’s face, eyes and mouth.” This is not sex-positivity; it is hatred of women. According to one survey, boys are inducted into this ritualized hatred at an average age of 11.

Read the whole thing. It’s important.

You might be thinking: no wonder those three guys are so against porn — they’re all three conservative Catholics. Well, have I got something for you: a reader send this jaw-dropping exchange from the Ecosophia blog, which is written by the occultist and authority on esoterism John Michael Greer. I’ve cited Greer from time to time in this space, when he was writing the Archdruid Report blog. We are very, very different people in terms of our religious commitments — he’s a polytheistic pagan, I’m an Orthodox Christian — but he writes some of the most interesting stuff on the Internet. This piece is definitely that. In it, Greer tells a reader that pornography is demonic — not symbolically demonic, but actually a tool of evil spirits — and offers him pagan spiritual advice for conquering it.

Once a week, Greer takes questions from his readers. On Monday, a reader wrote to say that he was struggling with a demon of pornography. The anonymous reader follows up on a post he wrote the previous week, in which he said:

I’ve been doing some journaling on my porn use. My subconscious seems determined that it is a major source of my issues, and I’m trying to get to the bottom of it. When I asked why I use it, the first thing which came into my head was “Because I tell you to.” This sort of thing has never come up during journaling, and it felt rather alien to me.

Greer told him that yes, this sounds like a malign spirit.

Well, this week, the man was back, and said to Greer, of the malign spirit:

It seems to be hammering home on a few points, all of which seem intended to do one of a few things: break me down so I can’t resist it; keep me sexually aroused so I feel the need for porn; make the rest of my life horrible so I have no real reason to fight it; or keep me from making it harder for myself to access porn.

1) My life is currently a mess. You mentioned last week something about demonic obsession, and how victims aren’t entirely sane. I’ve been questioning my sanity for a while now (this is part of why I picked up journaling), so it may fit me. Does this sound like the case for me?

2) I think my main priority for now is to get rid of this thing. One of the only ways I know of is to practice a daily banishing ritual and get good at it. Are there other steps I can take to get rid of it? I assume using porn less will weaken the link, but am I correct, and are there other ways to rid myself of it?

3) If this sort of spirit is common, might it explain the existence of a traditional prohibition on pornography in several spiritual traditions?

4) You mentioned last week it likely feeds on me during orgasm. Would you mind elaborating what you meant by that?

5) I’ve been looking at the no-fap [anti-masturbation]/porn-free communities online and find that a lot of people describe porn as a demonic force which takes over their lives. Nearly everyone clarifies it’s a metaphor, and one of the things which this spirit is trying to do is question my sanity whenever I pay close enough attention to notice it. Thus, do you think part of the reason materialism is so popular among so many dysfunctional people might be malevolent spirits pushing it, to keep them from thinking that a malevolent spirit even exists, let alone might be affecting them?

Greer answered, in part:

1) That’s hard to say. Our society right now is clinically insane — I mean that in the most literal sense — and so it’s very difficult to tell what counts as the kind of personal craziness that might be the product of obsession, and what is the collective craziness that pervades our culture.

2) Yes, using less porn will starve it, but of course it’ll double down at first, trying to get fed. If you go to the Magic Monday FAQ cited in the post, you’ll find instructions for a hoodoo protective bath, and for an amulet using salt and a bent nail. Both of those would be useful in your situation.

3) Yes, indeed it would.

4) Orgasm takes place on the etheric as well as the material plane, and just as you ejaculate on the physical plane, you extrude a certain amount of etheric substance — the substance of the life force — on the etheric plane. If you’re having sex with another person, that’s not a problem, because the other person’s body absorbs your etheric substance, just as you absorb the substance the other person extrudes; one of the reasons lovers so often feel nourished and healed by lovemaking is that each of them has taken in some of the other’s life force, which can then flow through the subtle body and fill in where there’s a shortage. In masturbation, there isn’t anyone else to absorb the etheric substance, and so a noxious spirit can dine on it — thus the feeling of weakness and depression so many people experience after masturbation.

5) Ding! Yes, exactly. Do you read science fiction and/or fantasy? If so, have you ever read C.S. Lewis’ space trilogy? He makes the point there that it’s a central strategy of malevolent spirits to keep people from believing in their existence.

The reader and Greer continue their exchange. Do I even need to encourage you to read the whole thing? I repeat: John Michael Greer is not a Catholic priest or an Evangelical pastor, but a practicing pagan cleric. You don’t have to believe in “etheric substance” or share all his religious beliefs, but as an Orthodox Christian, I have no trouble at all believing that evil discarnate entities feed spiritually on people who are in sexual bondage. Later in their exchange, Greer says it is likely that the chaos and darkness afoot in the world now has a lot to do with the Internet making hardcore porn easily accessible almost anywhere in the world. He also speculates about whether the collapse of fertility is connected to porn-connected events in the spiritual world.

Wild. Just wild. About demons, Greer advises his reader not to underestimate what he’s dealing with:

They are smarter than we are. That’s something to keep in mind: human beings are far from the most intelligent entities around.

St. Paul writes, in Ephesians 6:12:

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.

I believe it. So does the Archdruid. And I believe that for various reasons, human sexuality is the main theater of that spiritual war today. But you could have guessed that.

The post Porn Is Demonic, Says Top Occultist appeared first on The American Conservative.

December 10, 2019

An Ignatius Reilly Christmas

Here are hard plastic busts of my two main men: Dante Alighieri and Ignatius J. Reilly. Both were designed and 3D printed by Baton Rouge artist Kevin Lindholm. Check out the catalog of busts you can have made to order, in various styles, sizes, and colors — even as Christmas ornaments. All the Inklings are there, and some Catholic and Orthodox saints, and John Calvin and Martin Luther, and more.

And, of course, LSU head coach Ed Orgeron!

I get to take special credit for the new sculpture of Our Working Boy (here’s a direct link to the Ignatius bust.) At a fundraiser for our local classical Christian school, where Kevin teaches art, I bought his services to create a bust of any figure I wanted. Julie had already given me Kevin’s version of Dante for Christmas a couple of years ago. When I saw Kevin at Thanksgiving, I said, “I’ve got my bust idea!”

Last week, he presented me with the Ignatius you see above.

If you order now, I think he can get a bust of Ignatius, or any others, out to you in time for Christmas. But hurry! If your Yuletide lacks proper theology and geometry, you have nobody to blame but yourself.

The post An Ignatius Reilly Christmas appeared first on The American Conservative.

Building The Benedict Option: A Query

I want to put something out there to sympathetic readers of this blog and The Benedict Option. If this is not you, then don’t comment on this thread. I have been contacted by a reader who is seeking serious advice.

The reader is a conservative Anglican (he’s Episcopalian, but as a theological conservative, considers himself Anglican). He has a large parcel of land that he would like to use to develop a community of like-minded, theologically conservative Christian families, who will commit themselves to building what I would call a Benedict Option community — that is, a place where people who share Christian orthodoxy can build each other up, and raise families together. Ideally, he would like to place a monastery on that land as well.

The problem he has — and it’s a big one — is that he doesn’t know how to do it, or if it’s possible, given the division among churches. He is aware that the Anglican churches, as a body, are in a very weak position regarding orthodoxy, at least in the United States. But he does not like the idea of a Catholic or Orthodox monastery on the land, because non-Catholics and non-Orthodox would not be able to enter into the full liturgical life of the monastic community (by which he means, take Communion). And, of course Orthodox Christians could not receive communion at a non-Orthodox church, nor could Catholics receive communion at a non-Catholic church.

That is a fact that is not going to change in our lifetimes, if ever.

I ended up speaking by phone this morning to the reader. We agreed that it is a fact of church life that the churches best equipped to endure this new Dark Age are those who are more committed to particularity — which is to say, exclusivity. The reader is very conservative, theologically, and said he is against false ecumenism, and false irenicism — that is, he doesn’t believe Christians should water down their beliefs for the sake of unity. And yet, he understandably would not want to give his land over to building a community that would exclude Christians like him from communion.

I told him that I don’t see a way around this problem, but that that could simply be my own lack of imagination. I know for a fact that I would love to live in a neighborhood of small-o orthodox Christians who were eager to live more communally. We have seen in our nondenominational classical Christian school that small-o orthodox Christians have much in common, and can work together well in building up a community. But a school has a limited mandate; it’s not the same thing as a neighborhood.

If there is to be a chapel or monastery on the property, it will inevitably have to exclude others. No Catholic monastery will turn away worshipers, nor would an Orthodox monastery. Except at the communion chalice. This is the sad reality of our brokenness as Christians, but that’s just how it is. It’s not hard to imagine resentment growing over that within this ideal community. And what would happen if people who moved into that neighborhood as believers in one particular Christian tradition began to convert to the form instantiated by the monastery? Wouldn’t that potentially cause deep strife, and a sense of isolation and even siege among the others?

You see the practical problems here. My reader is not at all hostile to Orthodox Christians or Catholics, and would welcome the chance to live among them. But he rightly worries that the inability to share the communion chalice would create fault lines in the community that could cause it to break apart.

Still, I think it would be a tragedy to let the perfect be the enemy of the good enough.

I offered to him to post about this on my blog, to see if any readers have good advice, especially from experience within this kind of community, if any exist. I know the Alleluia Community in Georgia is predominantly Catholic, and came out of the charismatic renewal in the 1970s, but has a significant number of Protestants living in it. Maybe some of you Alleluia folks can help my reader think through this issue. How do y’all do it?

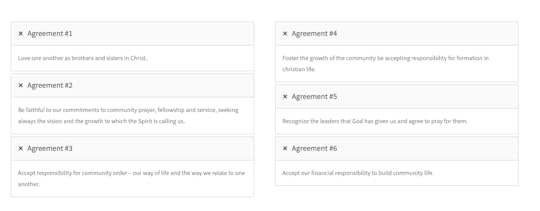

Here, from the Alleluia Community’s website, are the principles that bind them together:

So maybe the obstacle that my reader correctly identifies is big, but possible to overcome. I don’t know. What do you think?

I do know this, though: we small-o orthodox Christians need to be putting our heads together and being creative minorities, and thinking of ways we might go through the fog together. Just because this is a really knotty problem doesn’t mean that it can’t be solved.

I look forward to reading what you have to say. Again, if you aren’t going to comment constructively on this, don’t bother commenting. If you want to write to me privately, and ask me to forward your e-mail to the reader, please do: I’m at rod — at — amconmag — dot — com. Please put in the subject line “FOR YOUR READER.”

The post Building The Benedict Option: A Query appeared first on The American Conservative.

Postmodernism Destroyed His Church

I received the following e-mail from a reader, in response to my “Race, Identity Politics, and Evangelicalism” post. He gives me permission to use it, so long as I keep his name out of it. There’s a lot to think about here. By publishing it, I’m not necessarily endorsing his conclusions. I just think there’s something here worth considering. Here we go… — RD

—

I can speak from first-hand experience on the effect of Race, Identity Politics, and Evangelicalism on the evangelical church. I left my evangelical church for another, and when reading the short quotes from the emailer you reference looks eerily familiar. I wonder if he is one of the several exiles from my former church.

There IS a significant theological difference between the woke and non-woke evangelical church. The woke-church is driven by the thoughts and assumptions of critical race theory. The traditional evangelical church is driven by the thoughts and assumptions of classic/traditional/stereotypical “American” understandings of the world (Locke, Adam Smith, Luther, Calvin, etc.). It is difficult to communicate how large of a gap this is. This long email proceeds in three parts:

1. Understanding the Postmodern Philosophy (of which Identity Politics is Part)

2. How I saw Postmodernism Break My Church

3. The way Identity Politics Goes to War With Evangelical Theology Under False Pretenses

Understanding the Postmodern Philosophy

As I have learned by reading books like Christopher Butler’s Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction, by keeping track of the fake academia scandal, and by reading actual postmodern works (Ibram Kendi, stamped from the beginning), it is difficult to communicate how significant the conflict (note: it’s a “conflict” not a “debate”) between woke church and evangelical church is. If you’d like the shortest possible summary of the dangers of Critical Race Theory, then watch this video of Jordan Peterson breaking it down (He is explaining the maniacal coherence of the “incoherence” of Postmodernism, and Critical Race Theory is Postmodernism’s assumptions applied to race relations). Here are some mind-blowing quotes, but I thoroughly recommend watching the entire thing. [Quoting Peterson:]

And then what happened is the Postmodernists came on to the scene, and they were all Marxists. But they couldn’t be Marxists anymore because [of how bad economic Marxism demonstrated itself to be a failure in the 1960s-1970s]. And so they started to play a sleight of hand: Instead of pitting the proletariat — the working class — against the bourgeois, they started to pit the oppressed against the oppressor. And that opened the possibility of identifying any number of groups as “oppressed” and “oppressor” and to continue the same narrative under a different name. It was no longer specifically about economics. It was about POWER, and EVERYTHING to the Postmodernist is about power.

And that’s why they’re so dangerous. Because if you’re engaged in a discussion with someone who believes in nothing but power, all they are motivated to do is accrue all the power. Because what else is there? There’s no logic. There’s no investigation. There’s no negotiation. There’s no dialogue. There’s no discussion. There’s no meeting of minds and no consensus. [Personal note: And for the Christian, it is worth noting that along these postmodern lines, there is no “truth” or “doctrine” either.] There is power.

And so since the 1970s, under the guise of Postmodernism, we have seen the rapid expansion of identity politics in the humanities. It’s come to dominate all of the humanities, which are dead as far as I’m concerned [Personal Note: As is whatever church that adopts “woke Christianity,” from my experience.] and a large amount of the social sciences.

More Peterson:

I would also caution people against making the assumption that what the radical post-modernists SAY they’re after has anything to do with what they’re actually after. Because they’re not after “equity.” They’re not after “tolerance.” They’re not anybody’s friend. Not at all. They’re all about POWER. They’re after power. And they use all this compassion language, which — you just have to scratch the surface of that and you find how fast that vanishes. They use all this compassion language and “I’m on the side of the oppressed” and all that posturing; it does nothing but mask the underlying drive for power. And that’s in keeping with their own damned philosophy, because for the Postmodernist, there is nothing but power.

That last one sounds pretty bad, and an overwhelming majority of people wouldn’t say that anyone THEY know would be so terrible as to “say” they’re for equality but truthfully be after “power.” But let the following quote ground the discussion in reality. It’s an explanation about how ideas like Postmodernism percolate:

The people who are animated by the Postmodern ethos are not generally in-and-of-themselves thoroughly possessed Postmodern philosophers. First off, they don’t know enough about Postmodernism or its underlying Marxism to make that claim. Imagine that the philosophy has an impetus. It has a core tendency to move in a given direction, as a body of ideas, a coherent body of ideas. And then imagine that it’s represented in fragments among people who find its tenants palatable. So, most student radicals, for example, are not 100% committed post-modernists. They’re probably like 10% committed post-modernists. When they’re not being foolish with their mob. They’re out being normal people.

But you get a mob together that’s animated by that Postmodern ethos, then the collective spirit that animates the Mob has that power-seeking proclivity, and that antipathy to Western-seeking ideals that we’ve been discussing.

For a long time, Christians have laughed off post-modernism by viewing it as incoherent. I’ve seen little pat dismissals of Postmodernism in evangelical culture (Ravi Zacharias comes to mind) like “Oh, you don’t believe in objective truth? So aren’t you saying it’s objectively true that there is no objective truth? That’s a contradiction!” But that changes when you realize that Postmodernists don’t believe in truth, but they do believe in POWER. All the incoherent inconsistencies that they spout out are not to persuade. They are to shame and conquer. So Matthew Shepard was not actually killed by a violent anti-gay bigot? Who cares about correcting the record? The point is cultural power, not truth.

Here’s an analogy, that is not so far off. You see someone online saying stupid stuff and making wild accusations about you. You challenge the truth of what they are saying. They respond with more incoherent blabber. Seeking to persuade the masses, you challenge this person to a public debate for all to see. They agree. You know you’re going to beat them at this debate, because you know (and you’re right) that what they’re saying doesn’t make any sense. So you arrive at your public event with your suit and tie, and all of your notes and power-point slides. You look over at the other podium, and you see that they don’t have notes. Instead, they have a gun, a club, a rope, and three large friends. You “lose” the “debate” in that public sphere.

The reason they were happy with their “losing argument” is that you don’t need a winning argument when you have a club in your hand. As for those who watch? “I don’t want to get beat with a club” is a convincing argument for those who are cowards as well as those who have never been taught courage and those who are ignorant of true enemies. It’s not a real club (at least not yet). Instead, it’s shame. It’s charges of “racism.” It’s all sorts of feelings and accusations that are wielded like a club and which drive good people into the corner with their tail between their legs.

How I saw Postmodernism Break My Church

While there are several reasons my wife and I had to (painfully) leave our church, the driving factor is something I can only describe as “Our church got woke.” And our church was NOT a liberal church. Our church’s statement of faith was borrowed from The Gospel Coalition’s website. We had deep theological teaching. We had a concentration on community. We had great worship. We had some management issues, but so what. Doesn’t everybody?

But then things started to get weird. The first issue was a sermon on the Civil Rights movement. Now, I’m fine with the Civil Rights Movement, but I didn’t know how the Bible said anything about the Civil Rights Movement, so I was a little perturbed that we dedicated an entire sermon to it. During that sermon, the guest preacher (a black member who eventually became an elder) made a claim that made me pause. He was speaking about the “racist” origins of the Southern Baptist Convention (with which our church associated). He bemoaned the sinful origin of the organization and said “They even believed that because of slavery, God had brought more Africans to faith! That’s wrong! That’s sinful!

Woke Point 1.

I winced, because what he just called sinful, I believed. I still believe it. No, it’s not a sufficient justification for slavery, but I do believe (as an accident of history and a proof of God’s sovereignty), that the slave trade exposed Africans to Christianity when they wouldn’t have been exposed to Christianity otherwise. I believe it in the same way I have no problem believing that “all things work together for the good of those who love God” and “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” For that reason, I have no problem believing that the trans-Atlantic slave trade led many people to saving faith. Plus, isn’t it objectively true? Regardless of the facts, I was troubled that one’s mental conviction on a factual (not theological) point was being called “sinful.”

So I emailed my pastor. And I had one of the weirdest conversations ever. Apparently, because of the Ethiopian Eunuch, Africa was already “evangelized,” so it was historically false that the trans-Atlantic slave trade spread Christianity in Africa. (Whaaaaaat?) Pay no mind to 1400 years in-between those events, the Muslim conquest, or the persistent tribal religions of Africa. The Ethiopian Eunuch evangelized Africa, so it’s historically incorrect to believe that God used slavery for some good.

Woke Point 2.

Oh yeah, I also got told that Jesus was black (not white) in that conversation. When I replied, “Wait, no. He was Mediterranean Jewish, not black. What do you mean Jesus was black?”, my pastor responded that “Well, he is what we’d call someone ‘of color’ so it’s essentially the same.” In stunned silence, I didn’t push the point.

Woke Point 3.

Later, in a Facebook post on the church’s page, that same pastor called Augustine of Hippo “African,” and I (not realizing who posted the comment) kind of laughed it off and slyly remarked that while he was the bishop of a city in Africa, he was actually Roman. Since “African” usually refers to sub-Saharan people with black skin, it is either wrong or confusing to call him “African.” We could call him “Berber” instead, if we wanted to. Had I known I was correcting the pastor instead of a random congregant, I never would have posted that. But my pastor (I am told) was extremely upset by this, and responded by calling me wrong, and also saying this is not the place to debate. (I know the etiquette of Facebook is fluid, but I can say the response certainly felt harsh).

Woke Point 4.

Later in the year, as police shootings were in the news, and Trump was a thing, we started having “discussions on race” in our church. These discussions were organized around racial identities. In the opening example to lead off the thing, the pastor asked all the attendees to raise their hands to see if someone was “from the South” and then against if someone was “from the North.” About 1/3 were from the north and 2/3 were from the South. So he asked, “So, we should be loving our neighbor in the church. We all know that. With this in mind, who should be giving up power in the church in order to love their neighbor.”

Note the phrase “Power.”

Woke point 5

In a list of books our pastor recommended, one was Stamped from the Beginning, by Ibram Kendi. Not knowing anything about this guy, I bought a copy and tried reading (hoping to come to some common ground with my pastor who I was personally struggling with). I was ABSOLUTELY shocked by what I read. I noticed the absolute militancy of the book, and emailed my pastor again, and spoke to an elder (an elder is like a director on a board of directors, and the pastor would be and elder and the Chairman of the board). I pointed out the anti-Christian nature of his argument, and how twisted it is when Kendi saw beliefs about individual piety as wrong because individual piety allows oppressive structures like slavery to exist. An entire segment of the book tore Cotton Mather to pieces. Since our church at one point could be considered one of those “Young Restless and Reformed” congregations, my pastor recommending a book that ripped a Puritan to shreds was quite shocking.

Woke point 6.

We had a sermon on the #MeToo movement titled “Women in the Kingdom of God.” In response to many very public people being accused of sexual assault, our pastor noted that “Men are falling like dominoes” and that as we are seeing this:

“we witnessed the kingdom of God breaking into the kingdom of this world.”

I took issue with this, because often, the Kingdom of God is compared to people getting what they deserve, it is instead compared to people NOT getting what they deserve until the Last Day. (See Matthew 13:24). It seemed wrong to equate the Kingdom of God to “judgment” unless that judgment is on the Cross. But this wasn’t the judgment of the Cross. It was the judgment of courts and public opinion.

Woke Point 7.

Other quotes from this sermon include:

“In this culture, especially as a white male, if you have money and power and people need you — do you understand how that power is used? Especially on women.”

“Ever since the Roman Culture, we have idolized power. And women and minorities have felt the horror of this idolatry. From Rome to Greece to England to America we all have respected money and wealth and property ownership and power and this has led to great injustice like slavery and brutal patriarchy and misogyny even in the church.”

“Many times in conversation related to what women’s role the women begins with what are women allowed to do rather than what women are empowered to do. I want [our church] to be a place where women are empowered to do ministry in the church. What are women EMPOWERED to do in the church.”

Note the persistence of “power.” Note the progression of “Rome to Greece to England to America.”

Woke Point 8.

In our church’s small group (basically a home-meeting connected to the church, not led by a pastor, but by church volunteers through the church), the subject was to discuss the sermon. After deliberately asking the women what they thought of the sermon first, the subject was opened to the men. After about five seconds of silence, I said “Well, I kind of hated it.” Silence. Why did you hate it? And at that point, I explained my point about the kingdom of God, and the conversation got REALLY awkward.

A week later, I was called to apologize for speaking out of place and hurting the women in the group. I was asked to meet with the small group members after church, at which point one of them said in exasperation once I wouldn’t recant my position, “Well, it’s clear you don’t care about women.” I left that meeting by agreeing to leave the small group (which I had been a part of for three years).

Woke point 9.

Also at this same time, our church nominated a new elder. That’s normal. What is not normal is that the elder wasn’t unanimously recommended by our current elders to be an elder. There was a slight controversy that he “took exception” to two articles in our statement of faith. Interesting, I thought. I wonder if he’s just being technical. What are the two articles that he takes exception to?

1. The infallibility of Scripture

2. The role of men and women

FULL STOP. What!? So the most basic unifying doctrine of evangelicalism and the single most controversial point of Christian theology in the modern age is what this guy takes exception to? Yes. I raised hell. I even publicly called him out when he cited a Bart-Ehrman-esque example of places the Bible has “mistakes” that “don’t really matter to the overarching narrative.” I wanted to know how I could share my concerns with others in the church. I was told (by the same pastor) to basically just do it among my friends, and not sow division with big public debates.

The elder was confirmed.

Woke point 10.

Eventually, my wife and I left. It was just waaaay too much. There were some really good people at that church, including a pastor (not the main one) who was excellent, thoughtful, pastoral, and available. And no, “woke church” wasn’t the only problem. But as I observe over and over again, when you have one problem, you have lots of other problems. Now I hear from our old friends that the one good pastor and the only elder who voted against the exception-taking elder are stepping away from their roles (not for any “explicit” reason, but just because life is moving them in other directions.)

And I can’t express how far of a fall this was for our church. We started off with teachings, recommendations, and books from conservative theological stalwarts like John Piper (who pretty much invented the term “complementarian” to counteract the egalitarianism pushing through the church). Then we were getting recommendations on books like The Ragamuffin Gospel by Brennan Manning (Laicized priest who is basically preaching universal salvation). Then we were getting recommended Divided by Faith, a somewhat-CRT view of race relations in the American church by Michael O. Emerson and Christian Smith. Then we were being recommended Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram Kendi. IBRAM KENDI!!????!!!! This happened in less than five years.

I know of several people who have left the church. Many people are just drifting away. It’s hard to say why (though I know at least some are leaving for similar reasons as I am leaving). While I was still on the member email list, I know from a limited data-set that donations went down as Wokeness went up. But I’m almost afraid to say that because it’s not really the point. The real issue is the absolute loss of the Gospel. If it takes money to get people to pay attention, I’ll convince people with that. I just don’t know how to make people see what’s going on.

People don’t have ideas. Ideas have people.

Identity Politics Goes to War with Evangelical Theology Under False Pretenses

The two philosophies of Evangelicalism and Identity Politics are at war, even though none of it is done explicitly. To talk about the war explicitly would be to actually name things. It would be to connect words to meanings. Abstract concepts would be made somewhat concrete to the point where they could be judged. That is anathema to Postmodernism. With Postmodernism, prepare to talk about what you “feel” and “experience” and “power” and “perspectives” but never end at the “truth.” And while of course it is difficult to actually know the truth, in Postmodernism, there isn’t even a “they believe that for that reasons, and we believe this for this reason.” Instead, Postmodernism says “They believe that. [drops head, sighs, and frowns in sad moral disapproval].”

Identity Politics corrupts evangelicalism because it uses things that LOOK like evangelical doctrines, but aren’t. It is a doctrinal wolf in sheep’s clothing. For example:

Oh, you believe in original sin? Well, let me tell you about unconscious bias.

Oh, you see how entire nations were called to repent in the Bible? Let me tell you how this nation needs to repent of its racist past.

Oh, you see how Peter was corrected when he treated Jews and Gentiles differently? Let me tell you how we should correct our country when it treats illegal immigrants and citizens differently in our laws and policing.

Oh, you want to make the Christian gospel good news for all people? Let me tell you what you need to say to minorities and people of color to bring them into the church.

Also, there are several tropes of Identity politics that flip essential Christian doctrines on their head. For example:

What is “privilege”? How does it differ from something you should be grateful for. You parents are rich. Is that something you should be grateful for? Is that something you should see as a blessing that God has bestowed on you so that you can give yourself to others? Or is that evidence of your oppression? Should you be grateful for that thing, seeing it as a thing from God and not a result of your own merit? Or does calling that gift a “thing from God” just a justification for your own power over the marginalized? Shouldn’t you renounce it instead of being grateful for it?

The Woke Christian will love to talk about the poor widow Zarephath that Elijah fed (1 Kings 17), but they won’t really know how to talk about Naaman being favored by God. (2 Kings 5). So they make the story about Naaman about the poor (oppressed) slave girl who tells Naaman about Elisha. Why would God help a man who is not only rich, but a commander who CAPTURES SLAVES in Israel? Yet Jesus puts Zaraphath and Naaman right next to each other (Luke 4:27).

Let’s take LGBT issues. Are these people beset by an iniquity of their desires and a sin in whatever action enacts those desires? Or have they been “oppressed” by our prejudice, as we do not see the “value” they have in our society and congregations?

Likewise, what is “generosity”? If the default is to surrender your property and possessions, what is charity? Is advocating for a government program delivering healthcare to the poor what God calls us to do? Is it actual healthcare that God intends to provide to people or is it the heart that willingly gives up possessions that God wishes to institute?

For the old guard, the giving of money was Christian generosity, and the tax deduction was society recognizing the goodness of that generosity. For the new generation of Woke Christians, the government program that delivers healthcare is God working in the world. Individuals supporting such programs with a vote or with advocacy is God working in that individual.

(Note: This says nothing about whether such programs are good programs. They may be. But if your “charity” is “taxed” — forced — that is a radical departure from an evangelical Christian understanding of generosity.)

Most Christians KNOW something is wrong, but are absolutely unprepared to understand this. I feel like a lunatic when I get started on the subject. And I find sympathy with that feeling with Jordan Peterson in that same video:

It’s unbelievable. You know, every day, I come across new policy statements of this sort that make my jaw drop! It’s like as Canadians we’re so accustomed to our political system working that we don’t pay any attention to it. So when you ring the bell and say “Hey. There’s a problem!” People think, “No there’s not. This is Canada for Christ’s sake. There’s no problems here. YOU must be insane.

Canadians = Evangelical Christians. Political System = Theological Training. Canada = Whatever evangelical church you happen to be in that starts to get “Woke.”

Conclusion

I’m not saying that the stereotypical version of American Christianity was good, and that we should return to it. No, of course not. There were SOME things that need correcting, but the essential core of Evangelicalism is good and should be preserved, even as there are plenty of things to correct.

Instead, what I am saying is that Postmodernism is rotten to the core despite any fleeting appearances. Yes, the Postmodern fleece is quite soft, but the teeth are sharp. The wolf beneath is quite vicious as soon as you start to get close.

[End of letter.]

The post Postmodernism Destroyed His Church appeared first on The American Conservative.

Coach O & The Cajun People

Angelle Terrell is a Cajun who grew up in Lafayette (the capital of Cajun Louisiana), but who moved to Baton Rouge when she got married. For those outside of Louisiana, Baton Rouge, where I live, has a French name, and it’s in the southern part of the state (where the Cajuns are), but it is not a Cajun city. Sometimes it feels like Shreveport South.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing — it’s the capital of a state, the northern half of which is Anglo Protestant — but it does give you an idea of why a Cajun woman from a city only one hour to the west of Baton Rouge can feel like a cultural alien here. It’s a noticeably different culture. When I was a kid growing up in West Feliciana Parish, I knew that if we got on the ferry and crossed the Mississippi to Pointe Coupee Parish, we were in another country. That’s where Cajun Louisiana starts. People there spoke English with Cajun accents. They weren’t hostile or anything, but we knew that they were different. And I’m sure they said the same thing about us, because it was true. We were English and they were French.