Jennifer R. Hubbard's Blog, page 71

September 1, 2012

What characters really want

Two writers posted recently on making sure to address our characters' deeper needs, not just the external conflict in a story:

Laurel at Laurel's Leaves: "The story-worthy problem adds emotional stakes to your work, so that what happens to your characters and the decisions they make actually changes them deeply."

Laurie Halse Anderson at Madwoman in the Forest: "It’s pretty hard, if not impossible, to complete a novel without knowing what your character wants out of her life."

I encourage you to click over and read the posts. This concept is something I definitely pay attention to. I usually don't know my character's deeper needs or emotional quest early in the drafting process; something is driving him or her, but it takes me a while to recognize it. Once I know that deeper need, it becomes much easier to know where the story should peak, where it should end, which scenes truly belong, and how the subplots can link in to the main plot.

Also, for your amusement, check out Melinda Cordell's "Why I Haven't Written Anything" at The Storyteller's Inkpot. A sample:

"Distraction: Then write a bunch of random Tweets about your chickens!

Me: No, I need to stay off the internet and use my time constructively.

Distraction: Ha ha! Now that's funny!"

I definitely encourage reading the whole thing, because it gets into the critical voices in our heads, and the ways they can sabotage us, but it's funny, too.

Laurel at Laurel's Leaves: "The story-worthy problem adds emotional stakes to your work, so that what happens to your characters and the decisions they make actually changes them deeply."

Laurie Halse Anderson at Madwoman in the Forest: "It’s pretty hard, if not impossible, to complete a novel without knowing what your character wants out of her life."

I encourage you to click over and read the posts. This concept is something I definitely pay attention to. I usually don't know my character's deeper needs or emotional quest early in the drafting process; something is driving him or her, but it takes me a while to recognize it. Once I know that deeper need, it becomes much easier to know where the story should peak, where it should end, which scenes truly belong, and how the subplots can link in to the main plot.

Also, for your amusement, check out Melinda Cordell's "Why I Haven't Written Anything" at The Storyteller's Inkpot. A sample:

"Distraction: Then write a bunch of random Tweets about your chickens!

Me: No, I need to stay off the internet and use my time constructively.

Distraction: Ha ha! Now that's funny!"

I definitely encourage reading the whole thing, because it gets into the critical voices in our heads, and the ways they can sabotage us, but it's funny, too.

Published on September 01, 2012 17:39

August 30, 2012

Blogoversary with Heathcliff and House

Well, my friends, I've had a blog--starting at LiveJournal--for five years now. If you've been with me all this time: thank you! And if you've been with me for part of this time: thank you! And if this is the first post of mine you've ever read: welcome and thanks! It boggles my mind that I have been able to keep a single electronic "home" furnished for that long in this ever-changing world of the internet. I started mirroring this blog on Blogspot a couple of years ago, and I plan to continue at both locations indefinitely.

To celebrate this blogoversary, I thought I'd repost this old favorite of mine, which discusses Wuthering Heights, among other things. The original post (Jan. 10, 2009) is here if you want to see the brilliant, perceptive comments people left then. More great comments are welcome here, as always. ;-)

Enjoy!

****************************************

****************************************

The Heathcliff-House Theory on the Appeal of Unlikable Characters

I've just finished reading Wuthering Heights, which I probably should've read years ago. You know the situation--somehow a classic (or fifty of them) slips by you, and you just nod knowingly whenever it's mentioned, and hope nobody asks you about specific details. Anyhow, I no longer have to cover my ignorance about WH.

Somehow, before I read this, I had gotten the idea that Heathcliff was a romantic hero. Aloof and mysterious, but mouth-watering nonetheless. Sort of like Darcy in Pride and Prejudice--maybe rather obnoxious the first time we meet him, but proving through his actions that he's made of better stuff. Somehow, I'd gotten the idea this was a love story.

I was mistaken. Heathcliff is generally pretty mean and selfish, and the woman he's obsessed with is just as mean and selfish. There are scenes where the two of them are berating each other, and each is saying the equivalent of, "Don't tell me you're miserable! I'm so miserable that all I wish for you is even more misery!" That's obsession, not love. Heathcliff abuses dogs, women, and servants. He loathes his wife and tells her so.

It made me think about unlikable main characters, and what draws us to them. Something has kept this book alive for more than a century; there's some reason it's a classic. Yes, it's marvelously creepy with ghost-story qualities, but is that enough? What's made Heathcliff appealing enough for people to read his story? Because I admit that while Heathcliff is too unpleasant for me to want as a real-life friend, he has some appeal as a fictional character.

Heathcliff reminds me of a character on a TV show: Dr. Gregory House, from the show House. House is another character who's fun to watch, but you wouldn't really want to know him. He belittles his staff, rants at his patients, behaves as if he's above the rules, and evades every attempt of his friends to help him break a painkiller addiction.

So here's my Heathcliff-House Theory on the Appeal of Unlikable Characters:

1. Vulnerability helps. Heathcliff suffers for his infatuation. There are also a few times when he treats people kindly or at least fairly, when we expect otherwise. (His treatment of his son, though selfish at times, springs to mind here.) He's not unrelentingly vicious. Nor is House, who goes home to a lonely apartment and the comfort of nothing better than a vial of pills. We can sympathize with the pain of these characters, even if we don't admire how they handle it. We can see the gaps in the armor, and the blood dripping through those gaps.

2. Humor and honesty help. Both Heathcliff and House tend to toss out hard-edged comments so blunt and honest they make us laugh. (On House, fortunately, other characters get great lines too, particularly Wilson.) When the characters around them sink into petty squabbles or fussing over trivia, these main characters deliver lines like a bracing slap. In one scene in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff's servant is complaining about the uprooting of some black-currant trees. Heathcliff doesn't even wait to hear whom the servant is angry with. Guessing it to be one of the other servants, Nelly, he says, "What's your grievance? I'll interfere in no quarrels between you and Nelly -- She may thrust you into the coal-hole for all I care." And the complaining servant has been such a judgmental, ill-tempered jerk throughout the whole book that we also would like to see him thrust into a coal-hole. But we would probably be too polite to say so. Heathcliff and House sometimes say what we would like to say if we didn't give a darn what other people thought.

It's a sizable task to make an unlikable character appealing. The obvious risk is that the reader won't want to spend time in such a character's company. But it can be done.

To celebrate this blogoversary, I thought I'd repost this old favorite of mine, which discusses Wuthering Heights, among other things. The original post (Jan. 10, 2009) is here if you want to see the brilliant, perceptive comments people left then. More great comments are welcome here, as always. ;-)

Enjoy!

****************************************

****************************************

The Heathcliff-House Theory on the Appeal of Unlikable Characters

I've just finished reading Wuthering Heights, which I probably should've read years ago. You know the situation--somehow a classic (or fifty of them) slips by you, and you just nod knowingly whenever it's mentioned, and hope nobody asks you about specific details. Anyhow, I no longer have to cover my ignorance about WH.

Somehow, before I read this, I had gotten the idea that Heathcliff was a romantic hero. Aloof and mysterious, but mouth-watering nonetheless. Sort of like Darcy in Pride and Prejudice--maybe rather obnoxious the first time we meet him, but proving through his actions that he's made of better stuff. Somehow, I'd gotten the idea this was a love story.

I was mistaken. Heathcliff is generally pretty mean and selfish, and the woman he's obsessed with is just as mean and selfish. There are scenes where the two of them are berating each other, and each is saying the equivalent of, "Don't tell me you're miserable! I'm so miserable that all I wish for you is even more misery!" That's obsession, not love. Heathcliff abuses dogs, women, and servants. He loathes his wife and tells her so.

It made me think about unlikable main characters, and what draws us to them. Something has kept this book alive for more than a century; there's some reason it's a classic. Yes, it's marvelously creepy with ghost-story qualities, but is that enough? What's made Heathcliff appealing enough for people to read his story? Because I admit that while Heathcliff is too unpleasant for me to want as a real-life friend, he has some appeal as a fictional character.

Heathcliff reminds me of a character on a TV show: Dr. Gregory House, from the show House. House is another character who's fun to watch, but you wouldn't really want to know him. He belittles his staff, rants at his patients, behaves as if he's above the rules, and evades every attempt of his friends to help him break a painkiller addiction.

So here's my Heathcliff-House Theory on the Appeal of Unlikable Characters:

1. Vulnerability helps. Heathcliff suffers for his infatuation. There are also a few times when he treats people kindly or at least fairly, when we expect otherwise. (His treatment of his son, though selfish at times, springs to mind here.) He's not unrelentingly vicious. Nor is House, who goes home to a lonely apartment and the comfort of nothing better than a vial of pills. We can sympathize with the pain of these characters, even if we don't admire how they handle it. We can see the gaps in the armor, and the blood dripping through those gaps.

2. Humor and honesty help. Both Heathcliff and House tend to toss out hard-edged comments so blunt and honest they make us laugh. (On House, fortunately, other characters get great lines too, particularly Wilson.) When the characters around them sink into petty squabbles or fussing over trivia, these main characters deliver lines like a bracing slap. In one scene in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff's servant is complaining about the uprooting of some black-currant trees. Heathcliff doesn't even wait to hear whom the servant is angry with. Guessing it to be one of the other servants, Nelly, he says, "What's your grievance? I'll interfere in no quarrels between you and Nelly -- She may thrust you into the coal-hole for all I care." And the complaining servant has been such a judgmental, ill-tempered jerk throughout the whole book that we also would like to see him thrust into a coal-hole. But we would probably be too polite to say so. Heathcliff and House sometimes say what we would like to say if we didn't give a darn what other people thought.

It's a sizable task to make an unlikable character appealing. The obvious risk is that the reader won't want to spend time in such a character's company. But it can be done.

Published on August 30, 2012 17:06

August 28, 2012

10k a day?

When I first heard about Rachel Aaron's tips for writing 10,000 words a day (via a link on Nova Ren Suma's blog), I was a bit squeamish. I worry that there's been too much pressure on writers to churn out lots of words and lots of books and get faster and faster. And if you've been reading my blog for a while, you know that I'm not much of a word-count tracker. I tend to write a rough draft in a short-to-moderate amount of time, and then spend a much longer time revising, revising, revising. With such a process, word count isn't a useful goal for me most of the time. Only during that brief initial phase--where I spend about 10% of my writing time--do I add large numbers of new words to a project. The rest of the time, I'm reworking existing words, and maybe adding a few hundred or a couple thousand here and there.

But I'm intrigued by the idea of someone increasing her productivity so much, and I decided to read the article before scoffing (always a good practice). And, as it turns out, it's a very sane and sensible article. It's not about just trying to crank out words; it's mostly about tapping into our existing strengths. In fact, several of the techniques are aimed at increasing productivity without increasing the total time we spend writing.

I had already discovered a few of these for myself: jotting ideas for the next scene as a way to leave myself a reentry point when I break for the day; writing at the times of day when I'm most productive; writing in longer sessions when I'm first-drafting and it takes more brain energy to stay immersed in the world I'm building; skipping boring scenes.

Ms. Aaron also talks about collecting actual data on your writing process so that you can see what really works for you. This is something I haven't done because I'm not trying to systematically increase my output, but it makes sense.

By far the most difficult thing for me to do is "Know what you're writing before you write it." It's a concept I agree with, and it works when I can do it, but an awful big chunk of my writing process involves staring at the wall, or taking a walk, or washing my hair, while that knowledge bubbles up from the depths of my brain. Where does this story, or this scene, need to go next? is a question I'm not often quick to answer. Sometimes, in a rush, I try to force an answer, and that typically ends with me yanking out whole chapters and plotlines to rewrite them, much the way a knitter might rip out rows of badly executed stitches.

It's okay, though. One other benefit of looking at our process--whether through Rachel Aaron's suggestions or any others--is that we learn what works for us and what doesn't. We learn which parts of our process we need to continue, support, encourage, and make room for. We learn which tools just don't fit us. My favorite part of Ms. Aaron's article is that she sounds excited about her writing; she's having fun. Maybe some of her tips will work for you; maybe not. Whatever works.

But I'm intrigued by the idea of someone increasing her productivity so much, and I decided to read the article before scoffing (always a good practice). And, as it turns out, it's a very sane and sensible article. It's not about just trying to crank out words; it's mostly about tapping into our existing strengths. In fact, several of the techniques are aimed at increasing productivity without increasing the total time we spend writing.

I had already discovered a few of these for myself: jotting ideas for the next scene as a way to leave myself a reentry point when I break for the day; writing at the times of day when I'm most productive; writing in longer sessions when I'm first-drafting and it takes more brain energy to stay immersed in the world I'm building; skipping boring scenes.

Ms. Aaron also talks about collecting actual data on your writing process so that you can see what really works for you. This is something I haven't done because I'm not trying to systematically increase my output, but it makes sense.

By far the most difficult thing for me to do is "Know what you're writing before you write it." It's a concept I agree with, and it works when I can do it, but an awful big chunk of my writing process involves staring at the wall, or taking a walk, or washing my hair, while that knowledge bubbles up from the depths of my brain. Where does this story, or this scene, need to go next? is a question I'm not often quick to answer. Sometimes, in a rush, I try to force an answer, and that typically ends with me yanking out whole chapters and plotlines to rewrite them, much the way a knitter might rip out rows of badly executed stitches.

It's okay, though. One other benefit of looking at our process--whether through Rachel Aaron's suggestions or any others--is that we learn what works for us and what doesn't. We learn which parts of our process we need to continue, support, encourage, and make room for. We learn which tools just don't fit us. My favorite part of Ms. Aaron's article is that she sounds excited about her writing; she's having fun. Maybe some of her tips will work for you; maybe not. Whatever works.

Published on August 28, 2012 17:53

August 26, 2012

A tossed salad of ideas

Random thoughts for the day:

--Librarians are awesome. I got the chance to talk to several this weekend, and I was bowled over (once more) by their passion and dedication. Their hurdles get higher every year. Some policy-makers think they're expendable. But while the librarians are being nickel-and-dimed, they're constantly thinking of ways to get kids engaged with books, with music, with video, with technology, with all the resources libraries provide. Those of us who value libraries need to support them at every turn: with our money, our voices, and our votes.

--After talking to the librarians, I got to talk to some authors and readers. And a mysterious, rather bony gentleman in a dashing hat, as recorded by Beth Kephart.

--An astronaut leaves us as a storm called Isaac approaches. It's a poor trade.

--I was thinking of the kinds of sessions people ought to have at writers' conferences and came up with these, in addition to the traditional sessions on craft and marketing: ergonomics and carpal tunnel; business and taxes; legal issues for writers. Too bad I'm not on the planning committee for any conferences, but I'll just float these ideas out into the air. They may catch somewhere.

--Librarians are awesome. I got the chance to talk to several this weekend, and I was bowled over (once more) by their passion and dedication. Their hurdles get higher every year. Some policy-makers think they're expendable. But while the librarians are being nickel-and-dimed, they're constantly thinking of ways to get kids engaged with books, with music, with video, with technology, with all the resources libraries provide. Those of us who value libraries need to support them at every turn: with our money, our voices, and our votes.

--After talking to the librarians, I got to talk to some authors and readers. And a mysterious, rather bony gentleman in a dashing hat, as recorded by Beth Kephart.

--An astronaut leaves us as a storm called Isaac approaches. It's a poor trade.

--I was thinking of the kinds of sessions people ought to have at writers' conferences and came up with these, in addition to the traditional sessions on craft and marketing: ergonomics and carpal tunnel; business and taxes; legal issues for writers. Too bad I'm not on the planning committee for any conferences, but I'll just float these ideas out into the air. They may catch somewhere.

Published on August 26, 2012 18:48

August 23, 2012

Making the main character main

YALitChat takes place on Twitter on Wednesday nights. I haven't participated in a while, since I've been focusing on my latest manuscript, but I dropped in for a few minutes last night. The discussion was about characters and characterization. At one point, Chihuahua Zero (@chihuahuazero) tweeted this:

"One thing most people struggle with is the fact that the protagonist is overshadowed by the supporting cast."

I got to thinking about that problem a bit, and what to do when I run into it as a writer. I came up with two suggestions:

Give the main character bigger desires

Give the main character bigger flaws

Because I suspect that if side characters are more interesting than the main character, it's because the main character isn't driving the story (i.e., doesn't have much to do, doesn't have a big enough desire to launch events into motion), and/or the main character is too safe or too perfect. Flaws and vulnerabilities not only help us identify with a character, but they can open up new possibilities in the plot. Possibilities for conflict, for growth, for emotion.

I suppose I would sum it up this way: Characters have problems, and main characters have the biggest problems.

And thanks, Chihuahua Zero, for sparking this train of thought!

I want to mention some live bookish events happening soon (one involving me, the other not):

Saturday, August 25: PAYA (Bringing YA to PA), multi-author signing, library fundraiser, and book event. Pennsylvania's Leadership Charter School Advanced Learning Center; 1585 Paoli Pike, West Chester, PA 19380. Writing workshop starts at 10 AM; author panel for librarians also starts at 10 AM; author signings start at noon.

September 12, 6-7:30 PM: Teen Author Reading Night featuring Tara Altebrando, The Best Night of Your Pathetic Life; Sarah Beth Durst, Vessel; Gordon Korman, Ungifted; David Levithan, Every Day; Kate Milford, The Broken Lands; and a possible mystery guest! Jefferson Market Branch of NYPL, corner of 6th Ave and 10th St, New York City.

"One thing most people struggle with is the fact that the protagonist is overshadowed by the supporting cast."

I got to thinking about that problem a bit, and what to do when I run into it as a writer. I came up with two suggestions:

Give the main character bigger desires

Give the main character bigger flaws

Because I suspect that if side characters are more interesting than the main character, it's because the main character isn't driving the story (i.e., doesn't have much to do, doesn't have a big enough desire to launch events into motion), and/or the main character is too safe or too perfect. Flaws and vulnerabilities not only help us identify with a character, but they can open up new possibilities in the plot. Possibilities for conflict, for growth, for emotion.

I suppose I would sum it up this way: Characters have problems, and main characters have the biggest problems.

And thanks, Chihuahua Zero, for sparking this train of thought!

I want to mention some live bookish events happening soon (one involving me, the other not):

Saturday, August 25: PAYA (Bringing YA to PA), multi-author signing, library fundraiser, and book event. Pennsylvania's Leadership Charter School Advanced Learning Center; 1585 Paoli Pike, West Chester, PA 19380. Writing workshop starts at 10 AM; author panel for librarians also starts at 10 AM; author signings start at noon.

September 12, 6-7:30 PM: Teen Author Reading Night featuring Tara Altebrando, The Best Night of Your Pathetic Life; Sarah Beth Durst, Vessel; Gordon Korman, Ungifted; David Levithan, Every Day; Kate Milford, The Broken Lands; and a possible mystery guest! Jefferson Market Branch of NYPL, corner of 6th Ave and 10th St, New York City.

Published on August 23, 2012 16:20

August 21, 2012

Revision fatigue

There comes a point in the writing of every book where I become sick of the book.

Actually, that's a lie. There's usually more than one such point per book, and they usually come near the end of a round of revisions. Come to think of it, it happened with my short stories, too. That's how I knew I was done: when I could think of nothing else to do to the story, and I had been through every word of it so many times that the words were in danger of stale meaninglessness.

The mystery of writing is that you can bring a project to this point, be convinced the story is done through and through, backwards and forwards and inside out. Then you pick it up two months later and see you have used the same word twice in one sentence. And the marvel is that you read that sentence forty million times without ever noticing!

So revision fatigue doesn't necessarily mean the story is perfect. But it usually means that it's as good as I can make it for now.

Before I understood how deep revision could go, I didn't know about revision fatigue. Nobody warned me. I probably wouldn't have believed them. Writing was a joy, tra la, a magical world in my head--who sez it can be drudgery? Turns out that bringing the magical world onto a page that someone else can stand to read takes effort, and more than one try. More than five tries. More than fifty tries.

The good news is that revision fatigue wears off. Between revisions, it ebbs, until it's possible to face the next round, or the finished version, with fresh eyes and renewed love.

Actually, that's a lie. There's usually more than one such point per book, and they usually come near the end of a round of revisions. Come to think of it, it happened with my short stories, too. That's how I knew I was done: when I could think of nothing else to do to the story, and I had been through every word of it so many times that the words were in danger of stale meaninglessness.

The mystery of writing is that you can bring a project to this point, be convinced the story is done through and through, backwards and forwards and inside out. Then you pick it up two months later and see you have used the same word twice in one sentence. And the marvel is that you read that sentence forty million times without ever noticing!

So revision fatigue doesn't necessarily mean the story is perfect. But it usually means that it's as good as I can make it for now.

Before I understood how deep revision could go, I didn't know about revision fatigue. Nobody warned me. I probably wouldn't have believed them. Writing was a joy, tra la, a magical world in my head--who sez it can be drudgery? Turns out that bringing the magical world onto a page that someone else can stand to read takes effort, and more than one try. More than five tries. More than fifty tries.

The good news is that revision fatigue wears off. Between revisions, it ebbs, until it's possible to face the next round, or the finished version, with fresh eyes and renewed love.

Published on August 21, 2012 18:00

August 19, 2012

The glamor, it dazzles

It's official; I can barely move in my writing office. The available floor space has shrunk to the point where this room is an obstacle course. And it's not going to get cleaned up until I finish my current revision, in a couple of weeks.

I have begun to ask myself just what is all this stuff in here, anyway? And could it be illuminating to those who are wondering how much junk can accumulate in a writer's office? In the interests of scientific research and procrastination, here is a partial inventory:

--Boxes of promotional bookmarks

--An empty box

--A box of Kleenex

--Papers to be shredded

--A paper shredder

--An electric fan, to point at myself on hot days

--Stacks of books: books I'm reading, books I've read that need to be reshelved, books to be donated, books to be read someday in the future

--Candy wrappers, tabs from peel'n'stick envelopes, newsletters I've read and need to throw away

--A jug of water

--A pile of papers relating to my retirement account

--A pile of paid bills to be filed

--A box of files

--A bag of empty, reusable paper bags and bubble mailers

--A box of photo albums and other personal mementos

--A stack of royalty statements, records of this year's writing earnings, and this year's charity receipts

--A rolled-up throw to use when it's cold

--The bag I take to signings, filled with pens, bookmarks, handouts, and one copy of each of my books

No wonder I can't walk in here. I'm rather amused at how different this list is from the stereotype of the wild & crazy author. You would think I would have empty gin bottles and gifts from rakish ne'er-do-wells littering the floors. Instead of, yanno, financial records. Based on this list, the wildest thing that has happened in this office is the eating of some chocolate.

Turns out that most of the glamor of writing is what happens inside the writer's head and on the page!

I have begun to ask myself just what is all this stuff in here, anyway? And could it be illuminating to those who are wondering how much junk can accumulate in a writer's office? In the interests of scientific research and procrastination, here is a partial inventory:

--Boxes of promotional bookmarks

--An empty box

--A box of Kleenex

--Papers to be shredded

--A paper shredder

--An electric fan, to point at myself on hot days

--Stacks of books: books I'm reading, books I've read that need to be reshelved, books to be donated, books to be read someday in the future

--Candy wrappers, tabs from peel'n'stick envelopes, newsletters I've read and need to throw away

--A jug of water

--A pile of papers relating to my retirement account

--A pile of paid bills to be filed

--A box of files

--A bag of empty, reusable paper bags and bubble mailers

--A box of photo albums and other personal mementos

--A stack of royalty statements, records of this year's writing earnings, and this year's charity receipts

--A rolled-up throw to use when it's cold

--The bag I take to signings, filled with pens, bookmarks, handouts, and one copy of each of my books

No wonder I can't walk in here. I'm rather amused at how different this list is from the stereotype of the wild & crazy author. You would think I would have empty gin bottles and gifts from rakish ne'er-do-wells littering the floors. Instead of, yanno, financial records. Based on this list, the wildest thing that has happened in this office is the eating of some chocolate.

Turns out that most of the glamor of writing is what happens inside the writer's head and on the page!

Published on August 19, 2012 17:12

August 16, 2012

Mortality

One thing that has always driven me crazy is when people say, "Teenagers think they're immortal." I never thought that--as a teen or even as a child. I knew that people died, and that I could (and someday would) be one of them. I've written two YA novels in which death is a prominent subject because I know that teens do have to deal with it.

For teens who aren't living through war, famine or epidemic, the death of their peers usually comes through accident, suicide, or sometimes a serious illness. It's often unexpected, shocking in its suddenness.

We know that if we live long enough, we'll reach a point where losing our peers isn't as uncommon. Most of us expect those years to come well past middle age. But we don't expect to lose many friends who are in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

In the past three years, I've lost four friends who were in that age bracket: one to suicide, one to complications from a car accident, one to cancer, and one to cardiac arrest. Only one of those deaths came from totally out of the blue, but all of them seemed untimely, far too early. Each of those people taught me special things, and I carry their voices around with me.

The other day, the writer David Rakoff died at age 47--another in that age bracket. I didn't know him personally at all, but I had read his work and heard him read it, and there's a connection we often feel with people whose words we have read and enjoyed.

People say to live every day as if it's your last, but the truth is, most people really can't do that. If we did, we would not have pension funds and IRAs and nest eggs; we would never watch our diet or bother about our taxes; we would never do anything we didn't want to do. Instead, we strike a balance, putting some of our energy toward the future and spending some of it on the present, indulging ourselves every so often just in case it's later than we realize.

I hope this entry doesn't make me sound as if I have a terminal illness. I'm in good health, as far as I know. But circumstances are making me take stock, and I'm happy to affirm that when I look at how I spend my time, I'm glad I spend so much of it writing. My words may not last for centuries, as Shakespeare's have, but they will probably last for a while longer than I do.

It's not a bad way to spend my time. It is, in fact, a wonderful way to connect with others.

For teens who aren't living through war, famine or epidemic, the death of their peers usually comes through accident, suicide, or sometimes a serious illness. It's often unexpected, shocking in its suddenness.

We know that if we live long enough, we'll reach a point where losing our peers isn't as uncommon. Most of us expect those years to come well past middle age. But we don't expect to lose many friends who are in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

In the past three years, I've lost four friends who were in that age bracket: one to suicide, one to complications from a car accident, one to cancer, and one to cardiac arrest. Only one of those deaths came from totally out of the blue, but all of them seemed untimely, far too early. Each of those people taught me special things, and I carry their voices around with me.

The other day, the writer David Rakoff died at age 47--another in that age bracket. I didn't know him personally at all, but I had read his work and heard him read it, and there's a connection we often feel with people whose words we have read and enjoyed.

People say to live every day as if it's your last, but the truth is, most people really can't do that. If we did, we would not have pension funds and IRAs and nest eggs; we would never watch our diet or bother about our taxes; we would never do anything we didn't want to do. Instead, we strike a balance, putting some of our energy toward the future and spending some of it on the present, indulging ourselves every so often just in case it's later than we realize.

I hope this entry doesn't make me sound as if I have a terminal illness. I'm in good health, as far as I know. But circumstances are making me take stock, and I'm happy to affirm that when I look at how I spend my time, I'm glad I spend so much of it writing. My words may not last for centuries, as Shakespeare's have, but they will probably last for a while longer than I do.

It's not a bad way to spend my time. It is, in fact, a wonderful way to connect with others.

Published on August 16, 2012 18:16

August 14, 2012

Through the Looking-Glass

My last post by C. Lee McKenzie mentioned her love for Lewis Carroll's Alice books. I was always drawn to Through the Looking-Glass, because mirror images always seemed to present such a tantalizing alternate world. We could see it; it seemed that we should have some way of getting in there! As I got older, I began to appreciate the absurdity of Carroll's characters more and more: their dry wit, their quirkiness, the unpredictable way they twisted words. By the time I was in college, I found sentences like these priceless:

--"You know," he added very gravely, "it's one of the most serious things that can possibly happen to one in a battle--to get one's head cut off."

--"I mean," she said, "that one ca'n't help growing older.""One ca'n't, perhaps," said Humpty Dumpty; but two can. With proper assistance, you might have left off at seven."

--"I hope you've got your hair well fastened on?" he continued, as they set off.

Everything was unexpected; nothing was as it seemed. Carroll took familiar songs and poems, familiar characters from nursery rhymes, and familiar objects (like chesspieces and flowers) and mixed them up together, made them spout wacky dialogue and embroil Alice in unfamiliar problems (how do you turn pots and pans into armor? how do you dish out a cake before it's cut?). As much as I'm a fan of realism in literature--and was, even as a child--I kept a soft spot for this book, which probably helped hone my sense of humor. It's also a good reminder to let characters surprise one another, and to have fun with language.

source of recommended read: received as family gift

--"You know," he added very gravely, "it's one of the most serious things that can possibly happen to one in a battle--to get one's head cut off."

--"I mean," she said, "that one ca'n't help growing older.""One ca'n't, perhaps," said Humpty Dumpty; but two can. With proper assistance, you might have left off at seven."

--"I hope you've got your hair well fastened on?" he continued, as they set off.

Everything was unexpected; nothing was as it seemed. Carroll took familiar songs and poems, familiar characters from nursery rhymes, and familiar objects (like chesspieces and flowers) and mixed them up together, made them spout wacky dialogue and embroil Alice in unfamiliar problems (how do you turn pots and pans into armor? how do you dish out a cake before it's cut?). As much as I'm a fan of realism in literature--and was, even as a child--I kept a soft spot for this book, which probably helped hone my sense of humor. It's also a good reminder to let characters surprise one another, and to have fun with language.

source of recommended read: received as family gift

Published on August 14, 2012 17:01

August 12, 2012

Books of our youth: Alice in Wonderland

My series of guest posts on books that influenced us as young readers continues with C. Lee McKenzie.

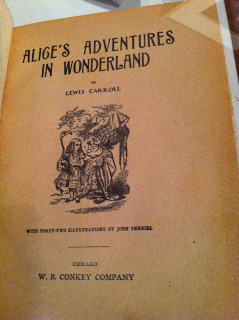

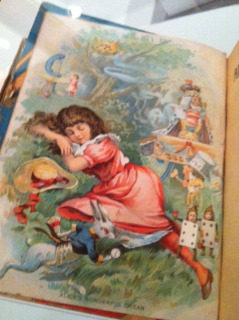

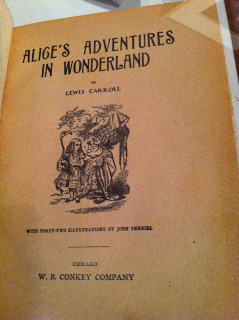

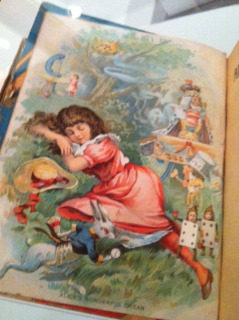

I was eight when I opened a 1941 edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. It started with this page:

followed by a daunting two page italicized poem in the style of the mid-eighteen hundreds. The poem gave even more about how the author had come to write this book. Here’s the first stanza, guaranteed to put you to sleep, right?

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence [sic]

Our wanderings to guide.

I didn’t know about character arcs or plots that built to climaxes, but still I would think that books without these essential storytelling elements would have bored me. I guess they didn’t because I read Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and I couldn’t wait to read Through the Looking-Glass.

So why did this book carry me away and stay with me as a book of my youth that I loved and that quite possibly made me into an avid reader, then later a writer?

I believe it was simply that Alice’s adventures with the White Rabbit, the Queen of Hearts and the Cheshire Cat transported me into a land where magical, mysterious, impossible events happened as commonly as brushing my teeth happened in my “real” world.

Over and over, I read about Alice having tea with the Mad Hatter or playing croquet with the impossible flamingo mallet. Over and over, I read how she grew and shrank, talked to a Caterpillar and the sad Mock Turtle.

Alice captivated my young mind and opened it to how boundless the imagination really is. She made me curiouser and curiouser until I couldn’t resist exploring my own imagination and finding just where it would lead me.

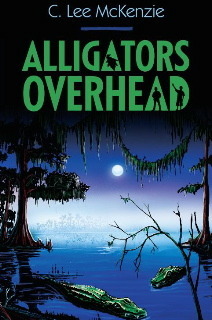

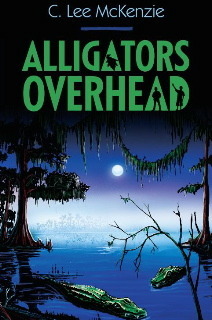

C. Lee McKenzie (@cleemckenzie on Twitter) is the author of the young-adult novels Sliding on the Edge and The Princess of Las Pulgas. Her new middle-grade adventure, Alligators Overhead, features alligators, witches, and a 12-year-old boy in a battle for his town's future. It's available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords. Or you can watch the trailer here.

I was eight when I opened a 1941 edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. It started with this page:

followed by a daunting two page italicized poem in the style of the mid-eighteen hundreds. The poem gave even more about how the author had come to write this book. Here’s the first stanza, guaranteed to put you to sleep, right?

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence [sic]

Our wanderings to guide.

I didn’t know about character arcs or plots that built to climaxes, but still I would think that books without these essential storytelling elements would have bored me. I guess they didn’t because I read Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and I couldn’t wait to read Through the Looking-Glass.

So why did this book carry me away and stay with me as a book of my youth that I loved and that quite possibly made me into an avid reader, then later a writer?

I believe it was simply that Alice’s adventures with the White Rabbit, the Queen of Hearts and the Cheshire Cat transported me into a land where magical, mysterious, impossible events happened as commonly as brushing my teeth happened in my “real” world.

Over and over, I read about Alice having tea with the Mad Hatter or playing croquet with the impossible flamingo mallet. Over and over, I read how she grew and shrank, talked to a Caterpillar and the sad Mock Turtle.

Alice captivated my young mind and opened it to how boundless the imagination really is. She made me curiouser and curiouser until I couldn’t resist exploring my own imagination and finding just where it would lead me.

C. Lee McKenzie (@cleemckenzie on Twitter) is the author of the young-adult novels Sliding on the Edge and The Princess of Las Pulgas. Her new middle-grade adventure, Alligators Overhead, features alligators, witches, and a 12-year-old boy in a battle for his town's future. It's available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords. Or you can watch the trailer here.

Published on August 12, 2012 18:38