M.P. Barker's Blog

July 20, 2015

Author Interview: Linda Crotta Brennan

Rivers catching fire and noxious gases so dense they fell people by the dozens. Sound like something out of a dystopian fantasy? No, we’re talking about mid-20th-century America, when rivers were clogged with factory waste, garbage, and sewage; industry spewed toxic chemicals into the atmosphere by the ton; and pesticides like DDT killed not just insects, but birds, animals, and humans. In When Rivers Burned: The Earth Day Story (Apprentice Shop Books), award-winning author Linda Crotta Brennan writes about the inception of the Earth Day movement and the growth of environmentalism in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. Linda is the author of more than a dozen non-fiction and fiction books for young readers on topics ranging from the American revolution to economics.

Rivers catching fire and noxious gases so dense they fell people by the dozens. Sound like something out of a dystopian fantasy? No, we’re talking about mid-20th-century America, when rivers were clogged with factory waste, garbage, and sewage; industry spewed toxic chemicals into the atmosphere by the ton; and pesticides like DDT killed not just insects, but birds, animals, and humans. In When Rivers Burned: The Earth Day Story (Apprentice Shop Books), award-winning author Linda Crotta Brennan writes about the inception of the Earth Day movement and the growth of environmentalism in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. Linda is the author of more than a dozen non-fiction and fiction books for young readers on topics ranging from the American revolution to economics.

Thank you, Linda, for sharing some Wicked Cool History stuff with us today.

Thank you for having me as your guest, Michele! I’m delighted to be here.

Thank you for having me as your guest, Michele! I’m delighted to be here.

How did you get interested in the Earth Day story?

I’ve always been interested in the environment. My husband and I are active with our local Audubon Society. Two of my three daughters are environmental scientists. So when my publisher at Apprentice Shop Books put out a call for proposals for books about pivotal moments in U.S. history, the story of Earth Day leapt out at me as the perfect topic.

In When Rivers Burned, you profile Gaylord Nelson and Denis Hayes, who were the driving forces behind the first Earth Day in 1970 and bringing environmental issues to the forefront of American political discussion. Do you have a favorite anecdote about each of these men?

Senator Gaylord Nelson had been trying to focus the nation’s attention on the environment for years. Only two weeks after he was elected senator, he organized a “conservation tour” for then-president Kennedy, but the environment was constantly overshadowed by the other issues of the day: the nuclear arms race, civil rights, Vietnam.

In 1969, Nelson was on a plane flying out to inspect an oil spill in Santa Barbara, California, when he picked up a magazine with an article about a “teach-in” on the Vietnam War. “That’s it!” he said. “Why not have an environmental ‘teach-in’ and get everybody involved!” That “teach-in” became the world’s first Earth Day.

Nelson hired Denis Hayes, who was a grad student at Harvard, to get “everybody involved.” It was a low-budget, low-tech effort. There was no internet or cell phones. Instead, Hayes had an “addressograph” with metal plates that he used to print out address labels to mail off the fliers he and his small but enthusiastic staff mimeographed in their tiny office. Yet with these primitive tools, they managed to create the largest demonstration in U.S. history.

You frankly address many controversial subjects in your book, including the zero population growth movement and climate change. How have readers responded to these challenging issues?

On the whole, readers have been very positive. Many have said my book made them realize how bad things used to be.

Do you think Americans are more sensitive to environmental issues than they were back in the 1960s?

In some ways they are. Americans are more aware of the issues. But they have also been desensitized by hearing so much about them. They’ve become blasé. This frustrates Denis Hayes. In one of his interviews with me, he complained that often environmentalists alert people to a problem and laws are passed so that the problem is averted. Then when nothing bad happens, the environmentalists are accused of being alarmist. But the problems are real, and we still need to pay attention.

You write about how the Earth Day movement led to major reductions in environmental pollutants, clean water and air legislation, and protection for endangered species. But you make it clear that there’s still a long way to go. What are the biggest challenges facing the environmental movement in the 21st century? Do you think we’ll be able to overcome them?

I’m not sure that I’m qualified to say what the biggest environmental issues are, but certainly climate change is right up there. All but a tiny fraction of scientists agree that this is a real problem, and that it’s caused by human activity. We’re already experiencing the repercussions, with more frequent, powerful, and deadly storms, extended droughts, greater temperature fluctuations, and so much more.

My husband and I have volunteered with the North American Butterfly Association’s survey for many years. I’m alarmed by the precipitous drop in the number of butterfly species and individuals in the past three years. There are also fewer bird species in my backyard. This saddens me.

What was the most surprising thing you learned in your research for When Rivers Burned?

I learned about the power of a handful of inspired individuals to make a difference. Senator Nelson and Denis Hayes didn’t have much in the way of financial resources, but they still managed to change global awareness about the environment.

You’re also the author of a fascinating book about an African-American regiment in the American Revolution—The Black Regiment of the American Revolution. What drew you to this topic?

You’re also the author of a fascinating book about an African-American regiment in the American Revolution—The Black Regiment of the American Revolution. What drew you to this topic?

Honestly, the publisher contacted me and asked me to write this book. I hadn’t grown up in Rhode Island and didn’t know the story of Rhode Island’s first regiment. But I was honored to have the opportunity to spread the word about these brave men.

Many people still don’t know that there was a mostly black regiment that fought in the American Revolution. (Not the Black Regiment of the Civil War.) The ranks of the Rhode Island First Regiment were filled by slaves who were offered their freedom in return for fighting.

At that time, slavery was widespread in the north. Newport, RI was the second largest slaving port in the country. After the Revolutionary War, attitudes toward slavery changed, partly as a result of the bravery of black soldiers. In the words of Dr. Harris, who had fought alongside the Black Regiment, “Liberty, independence, freedom, were in every man’s mouth. They were the sounds at which they rallied, and under which they fought and bled. The word slavery then filled their hearts with horror. They fought because they would not be slaves.” How could men who fought for freedom accept the enslavement of others? In the years following the Revolution, most Northern states passed legislation ending slavery.

You’ve written about the birth of the United States and environmentalism in the late 20th century, and have profiled 100 state heroines for the American Notable Women Series. Out of all the people and topics you’ve researched, do you have a favorite time period or historical figure, and why?

You’ve written about the birth of the United States and environmentalism in the late 20th century, and have profiled 100 state heroines for the American Notable Women Series. Out of all the people and topics you’ve researched, do you have a favorite time period or historical figure, and why?

I just finished a biography of an important figure of the Great Depression and World War II, which will be coming out next year, and I’m tossing around an idea for a book about the Industrial Revolution. So the 1700’s, the 1800’s, the 1930’s, the 1960-70’s…picking one is like having to choose my favorite child.

I’m drawn to stories about people who triumphed over great odds to make the world a better place, no matter what the era. I’m particularly interested in bringing to light the little-known story, such as the story of the Black Regiment.

You’ve also written an eight-part series for children called Simple Economics, covering topics from taxes to the stock market. Why do you feel it’s important for children to understand these topics at an early age?

Truthfully, the publisher asked me to write that series. But in our society, money is power, so yes, I think it’s important to teach children about economics. And in writing those books, I deliberately created a diverse cast, so all young readers might see themselves as active participants in their economy.

Thank you, Linda!

Thank you so much for having me as a guest of Wicked Cool History! I welcome readers to stop by my blog (where I showcase other marvelous authors and illustrators) at http://lcbrennan.blogspot.com/ and visit my website at www.lindacrottabrennan.com

May 26, 2015

Author Interview: Jane Sutcliffe, Historian and Biographer

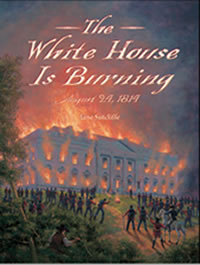

Today’s guest is Jane Sutcliffe, the author of more than two dozen nonfiction books for young readers. Her titles range from picture books to middle-grade, with biographies profiling presidents, figures from entertainment, business, and sports, and more. Her most recent publications are The White House Is Burning (Charlesbridge, 2014), about one horrific day in the War of 1812, Stone Giant (Charlesbridge, 2013), about Michelangelo’s creation of David, and a biography of U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz (Chester Nimitz and the Sea, Pelican Publishing Co., 2013). Thanks, Jane, for sharing some wicked cool history stuff today!

Today’s guest is Jane Sutcliffe, the author of more than two dozen nonfiction books for young readers. Her titles range from picture books to middle-grade, with biographies profiling presidents, figures from entertainment, business, and sports, and more. Her most recent publications are The White House Is Burning (Charlesbridge, 2014), about one horrific day in the War of 1812, Stone Giant (Charlesbridge, 2013), about Michelangelo’s creation of David, and a biography of U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz (Chester Nimitz and the Sea, Pelican Publishing Co., 2013). Thanks, Jane, for sharing some wicked cool history stuff today!

What sparked your love of history and biography?

When I was in fifth grade I had a history textbook that I remember very clearly. It was an anthology of biographies of famous people, like Walt Disney and Marian Anderson. We got the book on the first day of school and we were supposed to cover it in the next ten months. By that night I had read every chapter. There was something about reading about all these fascinating people and about what they had done that I found irresistible. After that I think I read every biography in the local library. I can still picture the long low shelf where they were stacked. I was so thrilled when I had the opportunity to write my own biographies of Walt Disney and Marian Anderson many years later. It was a way of paying respect to those people whose lives had so influenced my own.

Tell us a little about your newest book, The White House Is Burning. What inspired you to delve into this sometimes-overlooked bit of history?

I think the overlooked bits are the most fascinating. History is full of amazing stories and I love shedding a little light on them.

Here is what happened. A few years after 9-11, I was watching a special on the anniversary of the tragedy. The announcer happened to compare that day to other tragedies in American history, like Pearl Harbor and the burning of the White House in 1814. It caught my attention. I knew from school history courses that the White House had been burned by the British, but hearing about it in that context made me realize that, for the people who lived through it, that event was as terrible for them as 9-11 was for us. I started doing a little reading and started turning up these amazing first-person accounts of what happened that day. And it was not just the burning. There was a battle, an invasion, a hurricane, a tornado, and an explosion—all packed into one 26 hour period. There was a trash-talking villain and a pretty heroine, a fool, and an unsung hero. Talk about wicked cool! How could I not write about it?

In The White House Is Burning, you intertwine first-person accounts from both the American and British points of view with the narrative, which gives the book a real “you are there” feeling. How important is it to you to feel as though you’re walking in the shoes of your subjects? How do you achieve that feeling?

Even though I get excited about history, I know that to some people reading about the past sounds about as exciting as day-old mashed potatoes. So I try to spice it up. One way is by letting real people tell the story in their own words. These were living breathing ordinary people who had witnessed something extraordinary, and felt compelled to write about what they had seen. So I let the reader experience the shock and grief of that day through their words.

I also challenged the reader to think of the events of August 24, 1814 as if they were happening in the present day. I wrote an introduction that asks: What if you turned on your TV today and saw breaking news of the White House in flames? It’s hard not to feel stunned and horrified when you see it happening right in front of you. Those are the same emotions the residents of Washington experienced two hundred years ago.

You’ve written about historical figures from Sacagawea to President Obama. Of all the persons you’ve written about, do you have any favorites? Why?

I am frequently asked this question when I do school visits. My standard answer is that it’s as hard to choose a favorite biography subject as it is to choose a favorite friend. But I’ll tell you a secret: I do have two favorites. They are John and Abigail Adams. John Adams kept a diary his entire life and wrote in detail about his experiences and observations. Abigail was a gifted letter writer, and she and her husband kept up a steady correspondence through a number of long absences. Their writings document two amazing lives and made it easier for me to understand who they were and what motivated them. It also made it easier for me to include some great quotes and anecdotes.

I’ve found that research can be very addictive, and it’s sometimes hard to know when to stop. How do you decide when to stop doing the research and start writing?

I couldn’t agree more. Research is a bit of a guilty pleasure for me, too. You never know where you’re going to find that perfect little bit of information that’s going to make your book shine, so it’s tempting to want to look at just one more source, and then one more after that. Of course, it’s also a great way to put off writing and still feel like you’re accomplishing something. And it’s just so much fun! My rule of thumb—when I’ve consulted so many primary sources that I start to find errors in my secondary sources, it’s time to start writing.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced as a writer?

Time. Always time. There is never enough time to write all the books I’d love to write. I’d spend every day writing if I could, but I don’t think my family would be very happy with me. So, like everyone else, I try to balance what I have to do with what I want to do. I do try to write something every day, though. I once heard writer and historian David McCullough compare his writing schedule to rolling a tire down the road. As long as you keep hitting it just a little, he said, the tire will keep rolling. It’s when you stop that the tire falls over. I try to keep my writing from falling over.

What are you working on now?

I’m so glad you asked. My next picture book, Will’s Words: How William Shakespeare Changed the Way You Talk will be released by Charlesbridge in March 2016. And I’m also working on a picture book biography of Edward Hitchcock, a scientist who researched dinosaur footprints before the word “dinosaur” was even coined. His theory was that these mysterious footprints had been made by giant extinct birds. His ideas came to be regarded as kind of loony. But as they discover more and more about the relationship between birds and dinosaurs, modern paleontologists are beginning to appreciate just how right he was, and I’m so excited to be able to tell his story!

Cool! Edward Hitchcock is from my neck of the woods, here in Western Massachusetts, where we have a treasure trove of dinosaur footprints along the Connecticut River Valley. That’s terrific that you’re working on his bio–I’m looking forward to reading it!

Thanks, Jane, for sharing!

Readers who want to find out more about Jane and her books can go to her website.

May 11, 2015

Testimonials

“Michele Barker was good enough to come down to teach my high school advanced fiction class, and the session was just wonderful! She provided materials that showed them in a very real way what revision is really about. Then walked them through the material and talked to them about the material. So not only was it engaging but incredibly helpful. The students had a wonderful time with the writing exercise that Michele designed specifically to illustrate the material she was covering. This was one of the most productive and successful visits ever.”

–Barbara Greenbaum, Arts at the Capitol Theater Magnet High School, Willimantic, CT

“Having M.P. Barker visit your classroom is a perfect way to show students how content reading can benefit the reading of fiction. She described how she researched for her two novels by showing various examples of certain texts from that time. Also shared were her writing strategies and even a calendar of events for the story which helped her to stay on track. These real-life examples of editing and revising truly spoke to my students about the importance of those steps in their writing.”

–Mary Munsell, East Granby (CT) Middle School

“Thank you so much, Michele, for presenting to my class once more. Your visits continue to be the highlight of the semester for my students. As you know, the college freshmen who place into my developmental reading classes are often discouraged and frustrated readers. Many admit that yours is the first book they’ve ever read cover to cover, and they credit your anticipated visit to our class as their motivation. As a published author, you rank a certain level of “celebrity” for them, and meeting you face to face makes them feel important, makes reading your book important. And you never disappoint. You are professional yet approachable, and your amicable, unassuming manner puts them immediately at ease. You bring not only the book to life for them, but the history as well. … Thank you again, Michele, for making a difference.”

– Paula Bernal, Developmental Reading & Writing Instructor, Springfield Technical Community College

“Michele’s presentation to first year college students was quite revealing and surprised some of the students who had no idea how difficult writing could be. Her knowledge of and skill in historical research contributed to the creation of a highly interesting book so germane to today’s problems of conflict and resolution. This is a great book to teach critical thinking skills!”

– S.M. Santucci, Adjunct Professor, Holyoke Community College, Cambridge College

Comments from Students:

“…[T]he fact that a 700 page manuscript became a 300ish page novel floors me. I know cutting extra stuff out is a big part of editing/revision, but I can’t believe all that information can be dumped with enough to still make a coherent and compelling novel. I was also surprised at how many rejections you can get before you get one acceptance- and how far you still have to go before publication. I really liked learning about her method of organization, and that there is no wrong way to organize unless you leave it unorganized….I also greatly admire how much research was put into those books. That’s a step I tend to forget, but it really makes all the difference. Nothing is worse than reading something and thinking the author doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”

–H.S.

“One thing I learned from Michele being here, is that there are a lot of different things that can be done to keep organized. I liked her method with the calendar, where she had pieces of paper with the scene attached to the days they were happening, like a timeline…One thing I will try and use in my writing as I move through this revision phase is to rewrite my pieces at least three times. Also to write down questions I have as I’m writing about possible new ideas and characters, because it could help me later in the process if I get stuck.

–H.F.

“I was surprised by how relatable her revision and editing process story was. I found a lot of my habits in her presentation. It was kind of like an, “Oh, I’m not the only one,” type of thing. I was also really surprised on how much she was able to cut down. 700 pages to 300 is an insane difference….I loved how she organized almost her entire book into sections that would really help me not be intimidated by editing a book that long. All of her organization techniques were fascinating. They way she cut her book into a timeline, her evaluation sheets, even her rejection letters were organized. I could tell that all of that organization really helped her, and maybe if I ever get stuck on revision I’ll organize everything too… She really improved on her writing when she took a second glance and rewrote what she was trying to say/get across. I think that would be a good strategy if I ever get stuck on something, or I am not liking how something is coming out. It’s a good ‘refresh’ button.”

–J.D.

“I couldn’t believe how much she had to cut down on her book- from 700 pages to-what-350? Good grief! Also, I was surprised how she actually started writing the book. Bribed with dinners! Ha! Oh! Here’s one more- I was taken off guard to learn that one of her methods for revising her work was tables. The scene, the purpose of the scene, how to make it better, etc. How clever is that? I learned a lot of things, but the one that sticks with me the most is ‘show, don’t tell.'”

–S.G.

“One thing that surprised me was her ability to shrink her work, I know personally within the 2-4 pages I write I get attached to unnecessary sentences so I can only imagine how many she had to get rid of if she started out with 700 pages and end with 300…One thing I learned was that strategy and organization in writing is more important than I thought. Like the charts she used to keep track of where her characters were was neat and definitely something I might try while writing longer pieces.”

–H.A.

“I learned that changing the point of view of a piece can really alter it (i.e. what I did with my drafts) and that there is no such thing as revising too many times. I also learned that cutting down pieces of a draft does not mean that a scene was bad, it just means that it wasn’t as important as the others…I’m probably going to use the calendar timeline that she brought in. I have a lot of issues with orienting my stories in time, especially if I’m doing time skips and things, and it looked like (and from what she said, was) a very helpful tool.”

–N.J.

“1 thing that surprised me: How organized she was. That board she had with the time line of her story was very thorough, it was almost a story in itself.

“1 thing I learned: There is a fine line between having too little research and too much research. You can’t dump information on your reader and expect them to stick around for very long.

“1 thing I’ll apply to my writing as we go through this revision phase: Organization. I thought it was astounding how much detail that Michele went into in planning how her story would go. But even with all that paper, she kept it all in one place and organized.”

–E.S.

March 31, 2015

Mending Horses: Image Gallery

Mending Horses: Frequently Asked Questions

From John J. Jennings, Theatrical and Circus Life; or Secrets of the Stage, Green-Room and Sawdust Arena

Where did you get the idea for Daniel joining a circus?

When I started writing A Difficult Boy, I didn’t have a sequel in mind. But as I was editing the first book, I realized that Daniel’s story really wasn’t finished. I kept wondering what he would do and how he would manage in the world, especially since he’d spent most of his life being told what to do. So I thought he might look for Mr. Stocking, the peddler from the first book, for advice. Because Daniel is a natural horse whisperer, I knew he would want to do something with horses, and I at first thought he might get involved with the military, in the cavalry service, but that didn’t feel right to me. So I began thinking about what other jobs might involve horses, and the circus seemed like a natural fit. It also provided lots of opportunities to create interesting characters and situations.

Museum of the Early American Circus, Somers, NY

How did you do the research for Mending Horses?

Some of the background for “Mending Horses” came from work that I did as a historical interpreter at Old Sturbridge Village, which is a living history museum in Massachusetts. There, I learned about daily life of people in 19th-century New England. But working at OSV didn’t teach me about early 19th century circuses, so I did a lot of research at the Museum of the Early American Circus in Somers, New York. They have circus posters, account books and journals, publications, and more. The website of the Circus Historical Society was another excellent resource. Most important of all were the works of Stuart Thayer (1926-2009), who wrote wonderful books and articles about pre-Civil War American circuses.

From William Guild, A Chart and Description of the Boston and Worcester and Western Railroads

I also had to do a lot of research about the Irish immigrants living and working in New England mill towns and working on the railroad. Brian C. Mitchell’s The Paddy Camps: The Irish of Lowell, 1821-1861 was a wonderful resource for some of that information.

I learned about the Western Rail Road from newspaper accounts of the time period, papers and records of the Western Rail Road, and from Dennis Picard, Director of Storrowton Village, who has done considerable research on Irish railroad workers in 19th-century New England.

To learn more about the horse training elements of the story, I attended demonstrations by horse trainers like Monty Roberts, read lots of books about horse whispering, and had the opportunity to observe a young woman who retrains abused horses. I also read about 19th-century horse trainers like John Rarey, who was known for his humane methods of training.

Is Mending Horses based on real people, places, or events?

With the exception of Farmington, Massachusetts, and Chauncey, Connecticut, all the towns and villages mentioned in the book are real places. All of the people in the story are fictitious, except for the landlord at the inn in Springfield toward the end of book. There really was a Jeremy Warriner, whose inn was famous for hospitality and good food.

One event that actually occurred was the arrival of the Western Rail Road in Springfield, which happened on October 1, 1839—perfect timing for my story. I’d known that the railroad was under construction in the late 1830s and early 1840s, but it wasn’t until I’d already chosen the date for my story and decided to make Hugh a railroad worker that I learned of the October 1 event, which fit in perfectly.

While Mr. Chamberlain’s traveling show is fictitious, the stunts that his players perform are based on circuses of the time period. James “Grizzly” Adams (1812-1860), Dan Rice (1823-1900) and Joe Pentland (1816-1873) were just a few of the real-life performers who provided the ideas for my characters and their performances.

While Mr. Chamberlain’s traveling show is fictitious, the stunts that his players perform are based on circuses of the time period. James “Grizzly” Adams (1812-1860), Dan Rice (1823-1900) and Joe Pentland (1816-1873) were just a few of the real-life performers who provided the ideas for my characters and their performances.

How were circuses in the 1830s different from circuses today?

In the 1830s, circuses were just beginning to evolve into their present form. Circuses of the 18th century were primarily exhibitions of skilled horseback riding, and didn’t tend to travel. Traveling acrobats, magicians, singers, and jugglers generally performed separately from such shows. Menageries also tended to be distinct entities; at first they were more like traveling zoos than collections of performing animals. By the 1830s, however, show managers were bringing together menageries, equestrian acts, acrobats, comedians, and singers into large traveling shows. Shows might include things we don’t normally associate with circuses today, such as opera singers, displays of artwork, dramatic performances, or panoramas of historic events. Traveling tradesmen, peddlers, teachers, exhibitors, lecturers, and performers—what we might today think of as “sideshows”—often followed a circus in order to take advantage of the potential customers drawn by the larger show.

Courtesy of the Springfield History Museums

Why is Mr. Chamberlain’s show called a museum instead of a circus?

In many New England towns in the 1830s, there were laws that either prohibited traveling performers, or levied heavy licensing fees. So shows like Mr. Chamberlain’s Peripatetic Museum sometimes advertised themselves as museums or educational programs in order to evade those laws. In spite of such laws, newspapers, diaries, and other records show that acrobats, menageries, trick riders, and other traveling entertainers roamed throughout New England. Advertisements for such shows often went to great lengths to assure audiences that programs would be educational, morally uplifting, and “chaste.”

Names for circuses could get pretty creative and elaborate. Here are a few actual show names from the 19th century:

The Hippozoonomadon and AthelolypmimanthemYankee Robinson’s Colossal Moral Exhibition with Egyptian WallapussL.B. Lent’s Universal Living Exposition, Metropolitan Museum, Mastadon Menagerie, Hemispheric Hippozoonomadon, Cosmographic Caravan, Equescurriculum, Great New York Circus and Monster Musical BrigadeP.T. Barnum’s Museum, Menagerie, Hippodrome, Polytechnic Institute & International Zoological GardenJohn Robinson’s Great World’s Exposition, Museum, Aquarium, Animal Conservatory & Strictly Moral CircusW.W. Cole’s New Colossal Shows, Consolidated Three Ring Circus, Menagerie, Gallery of Wax Statuary, Russian Roller Skaters, Elevated Stage, Encyclopedia and RacesJ. Taylor’s Great American Double Circus, Huge World’s Museum, Caravan, Hippodrome, Menagerie and Congress of Wild and Living AnimalsWas it common to sell a child whom a parent didn’t want?

Well, technically it wasn’t legal to sell a child in New England in the 1830s. However, a parent could apprentice a child to a craftsperson or farmer, in effect giving the master under the apprenticeship agreement nearly complete control over the child. This arrangement was also referred to as an indenture, hence such children were sometimes called indentured servants. So when Mr. Stocking offers to “buy” Billy from Hugh Fogarty, he’s not literally buying the child, but offering to take Billy on as an apprentice or indentured servant. Such arrangements might happen if a parent were too impoverished to take care of his or her children. Parents also apprenticed their children in order to get them trained for a particular trade or craft. A parent might also hire a child out as a worker for day wages–any pay the child received would legally belong to the child’s parent or guardian.

Where did Mr. Stocking get the things he sold from his wagon?

In the 1830s, there were a lot of manufacturers of tinware in Connecticut, and they would sell their products through peddlers who traveled across the country. Peddlers also might add things like brooms, sewing supplies, patent medicines, books, and dozens of other products to their wares, which they might obtain by trading with storekeepers or wholesalers. In Mending Horses, Mr. Stocking’s cousin Sophie is married to a man who makes tinware and supplies Mr. Stocking with many of the goods he sells. Like other peddlers, Mr. Stocking also carries dozens of other products in addition to tinware.

Who are the people on the cover?

The cover was created by artist Richard Tuschman. A young actor/model posed for Daniel. Billy was played by the child of one of the artist’s friends. They did a photo shoot in Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and the artist developed the cover based on the photos from that shoot. The horse is named Lumpy, and according to the artist, “The biggest challenge was that Lumpy just wanted to eat the grass.”

November 25, 2014

Thanksgivings past and present

Just popping in here for a quick note on Thanksgiving, one of America’s oldest and most historic holidays. Here are five fun facts about Thanksgivings of the past.

Just popping in here for a quick note on Thanksgiving, one of America’s oldest and most historic holidays. Here are five fun facts about Thanksgivings of the past.

1 – Although Thanksgiving was celebrated throughout New England, Christmas festivities were often banned or at least discouraged until the mid-1800s. Ministers even preached anti-Christmas sermons condemning the holiday. (Okay, that’s really a Christmas fact–so sue me! Find out more about the lack of Christmas spirit in New England here.)

2 – New England’s early settlers also celebrated Fast Days, which were basically the opposite of Thanksgiving–instead of stuffing yourself with good food, you’d abstain from dining and meditate on your sins. Sounds like a real hoppin’ good time, doesn’t it? (You can learn about Fast Days here.)

3 – Until 1941, Thanksgiving was celebrated on different dates in different states. It was the governor of each state who would declare when Thanksgiving would occur. You can find an example of one of these proclamations online here.

4 -The Pilgrims probably did not eat cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, and pumpkin pie at the first Thanksgiving. Sugar was too expensive to sweeten cranberries and pumpkin pie, and white potatoes were not yet commonly eaten by either the English or the Wampanoag. (Go to the Plimoth Plantation Web site to find out more about what the Pilgrims did and didn’t eat.)

5 – Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), who wrote the Thanksgiving poem “Over the River and Through the Wood,” was more famous during her lifetime for her work to abolish slavery and advocate for women’s rights. (Find out more about Lydia Maria Child here.)

For more fun facts about Thanksgiving, check out these Web sites:

Find out the real history of Thanksgiving on Plimoth Plantation’s Web site.

Looking for some traditional New England Thanksgiving recipes? Check out Old Sturbridge Village’s Web site.

October 19, 2014

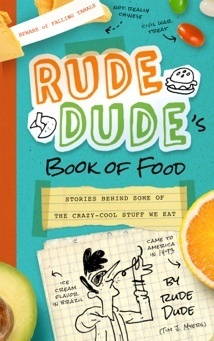

Rude Dude’s Guide to Food – Interview with Author Tim J. Myers

Tim recently stopped by to chat about some of the wicked cool history he discovered while researching and writing his new book.

Hi, Tim. How did you get interested in food history?

I suppose the most truthful answer is my plain old love of food! But an equally-accurate answer is that I wrote a picture book called A History of the World from a Hamburger-Lover’s Point of View (me being the Hamburger-Lover in question)–and an editor who rejected it said she’d be interested in a whole book on food history. Which, the world being its cutely ironic self, she also later rejected. But I had a ton of fun researching and writing the book, and it all turned out for the best.

I should add too that anyone who’s paying attention knows that a lot is changing right now in how we think about food, and I gradually came to realize how important many of these changes are. It’s more than just a shift away from, say, corn dogs and potato chips to healthier fare (notice that we’re currently in a kale revolution, for example). That’s important enough! But this big transition we’re in also has to do with maintaining the environment and encouraging economic justice around the world. So I relished the opportunity to get kids interested in food as more than–as it formerly was for me–just the stuff we put in our mouths.

Hey–”relished the opportunity”–unintentional food pun. Awesome, eh?

Ouch! You didn’t warn me that you’d be inflicting pun-ishment on the interviewer!

Where did you do your research?

All over the place. I generally do a good amount of online research, especially with the increase in quality sites on the Web, along with the burgeoning amount of junk. But I always use print sources too, and found many fascinating ones. In fact, this was one of those projects where I had to stop myself, time and again, from doing too much research, reading ahead in a mesmerizing book when I’d already gotten what I needed from it. That’s actually a genuine challenge sometimes! One of my most fervent wishes is to be reborn as a self-aware cat, in which case I’d give one entire life of my nine to the fascination of pure research.

I also learned about some amazing people, whom I mention in the book–like the Japanese scholar who tracked down the true origin of fortune cookies (NOT Chinese!). I even contacted a number of them and got wonderful responses from them.

There are lots of myths behind how various foods developed. How hard was it to sort out food fact from food fiction?

That’s a great question, because it can be a real challenge. Isn’t it funny how prone we human beings are to fanciful or just-plain-wrong explanations for things? I think that’s due to our instinct for storytelling drama, not to mention our desire to have things the way we want them. But for any historical work, Job One is to separate the wheat from the chaff. (Sorry! Another food pun, and a boring one).

The most difficult and interesting issue for me in this book was the famous story about Mongols putting raw meat under their saddles. Now a story like that–so dramatic and stomach-unsettling and cool and crazy–well, I of course questioned whether it’s actually true. And it’s cool enough to have become something like an urban legend, in the sense that it’s continually being retold–and when that happens, a writer has to be cautious, since all kinds of false things can accrete to actual historical practices or events. In retelling stories, people often just haphazardly glom layers of falsehood onto some kernel of truth.

Many of my sources said it was true, and others said it wasn’t, so I compared and analyzed and all the rest. In the end, I found enough trustworthy sources saying it happened, so I presented it as historical reality.

On the other hand, if some medieval Mongol rises from the grave and thrashes me for saying such a slanderous and disgusting thing about his people–well, then I’ll gather up my tattered soul and go back and revise.

What was the weirdest/grossest/most interesting thing you discovered in your research?

I got a huge kick learning about some of the more unusual Chinese dishes, most from times past, like deep-friend camel hump, cooked goose foot-webs, barbecued elephant trunk, and leopard fetus. But you stated it exactly right, since what’s “gross” to one person or culture may be delicious to another. I make that point in the book. I’ve lived overseas three times, so I’ve experienced myself how something that originally strikes you as odd or distasteful can end up being one of your favorite foods. When we first moved to Tokyo and went to the grocery store, it was–well, a trip! There were, for example, octopus tentacles in plastic bags for sale. We were delighted when we found a big jar of peanut butter and immediately bought it. But when we opened it at home, we found out it was miso, the stock for a Japanese soup–and we were all so disappointed. But that was silly, because now my whole family LOVES miso soup.

Hold off on the goose foot-webs, though–I’m open-minded, but my interest in water-fowl doesn’t extend that far.

What surprised you the most about writing and researching this book?

The biggest and best surprise was realizing just how much different cultures have actually been working together, mostly unconsciously, for centuries. Because new foods often travel, so to speak, crossing borders, and then are often developed in new ways by the new group. This isn’t true of all foods, of course, but it’s surprising how global humanity can be about food, and was even centuries ago. A lot of New World foods, for example–like chilis and tomatoes and potatoes–came to play a huge role in the cuisine of distant and very different cultures. Thai food, as I hope you already know, often uses chilis, to mouth-watering (and nose-reddening) effect. I loved learning that the ethnocentric, conflict-based view of history I was taught in school, though certainly true to some degree, wasn’t really the whole story. It’s as if our general human desire to make things better just keeps happening, and causes us to cooperate, sometimes in ways we’re not even aware of.

I mean, Good Lord!–thank you, Thai people, for the delicious things you’ve done with our American chilis!

What was your favorite part of researching and writing this book?

I’d have to say the stories I learned–like the perhaps-untrue one about Alexander the Great refusing to drink water until his thirsty soldiers also got some–or the one about the northern chieftain at a Chinese feast who ate a banana peel-and-all because he’d never seen one before and thought that was how you did it. And then all the rich detail of human life I encountered.

As just one example of the latter, I learned about the Chinese term for someone who’s puffed up and thinks he’s a big shot but actually isn’t. So I’m just waiting for the chance to call someone a “hat-wearing monkey.”

It was strangely fun too to become the Rude Dude character and just let loose in the ways I thought he would. I’ve always thought I’d like to go to a party in a gorilla suit, mainly because I think it’d be fun to act like a gorilla.

Does that make me weird?

Yeah–I know–it does.

Maybe, but being weird is much more fun, isn’t it?

Will Rude Dude be making any future appearances?

I have no idea. If the market speaks, I obey. I’ve gathered some research and ideas for a second book, but mostly just out of my own interest. Still, it’d be a blast. But out of my hands, I think.

You’ve written in a lot of genres—non-fiction, poetry, picture books, short stories, and more!—for audiences of all ages. Which genre is your favorite? Which genre is the most challenging? And why?

I don’t really have a favorite. In fact, that’s part of my great good fortune. Writing in different genres and for different ages, writing as a generalist rather than a specialist, isn’t all that practical. I think I’d do better career-wise and money-wise, probably, if I concentrated on one thing. But I’m constitutionally incapable of that, and being a generalist is one of the greatest joy-inducing realities of my life. It’s funny to me–”generalist” is such a dry, abstract term–sounds almost like some kind of doctor. But in my life it’s a fountain of pleasure and fascination. The whole world is my topic.

And even though writing a novel is harder than, say, writing a haiku, longer and more complex works don’t feel any harder to me, just because it’s such a delight to work on them.

What are you working on now?

I’m doing research and world-building for a–okay, ahem, get ready for the phrase I’ve come up with to describe it: a YA/adult crossover realist fantasy series.

That’s a bit of a mouthful, isn’t it?

For a long time I’ve been preparing to write a big story about three young people whose parents stand up to terrible political oppression, a decision that results in their children having to flee into what everyone considers a hateful, lifeless wilderness. One of the most pleasurable things about this, besides the story itself, is the opportunity to create my own world.

Sounds cool!

Thanks, Tim! Good luck with your new story!

Check out Tim’s web site to find out more about him and his other books.

March 18, 2014

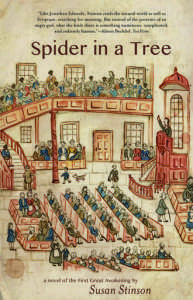

Author Interview: Spider in a Tree by Susan Stinson

In her historical novel Spider in a Tree, (Small Beer Press), Susan Stinson explores the Great Awakening of eighteenth-century New England through the eyes of minister Jonathan Edwards (best known for his sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God), his family, and his Northampton neighbors, as the religious revival ebbs and flows. With a keen eye for the details of daily life, the author examines the religious fervor of the times. Told from multiple points of view, the story shows a people whose religion was a strongly felt presence in almost every aspect of their daily lives. For some, this presence was a source of great joy; for others, it cast a shadow of fear, self-doubt, and guilt. Susan Stinson ably shows the varieties of religious experience and brings the reader vividly into the mindset of eighteenth-century Puritanism. It’s a challenging novel that delves deeply into a complex and sometimes confusing aspect of eighteenth-century New England.

In her historical novel Spider in a Tree, (Small Beer Press), Susan Stinson explores the Great Awakening of eighteenth-century New England through the eyes of minister Jonathan Edwards (best known for his sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God), his family, and his Northampton neighbors, as the religious revival ebbs and flows. With a keen eye for the details of daily life, the author examines the religious fervor of the times. Told from multiple points of view, the story shows a people whose religion was a strongly felt presence in almost every aspect of their daily lives. For some, this presence was a source of great joy; for others, it cast a shadow of fear, self-doubt, and guilt. Susan Stinson ably shows the varieties of religious experience and brings the reader vividly into the mindset of eighteenth-century Puritanism. It’s a challenging novel that delves deeply into a complex and sometimes confusing aspect of eighteenth-century New England.

Susan recently allowed me to interview her about Spider in a Tree.

Why Jonathan Edwards? What attracted you to the subject?

I live in Northampton [Massachusetts], just across from the Bridge Street cemetery. I was spending a lot of time walking and writing in the cemetery — which is a beautiful, green, quiet place. Members of the Edwards family are buried there, and there are two markers in his honor. I started reading the gravestones and became fascinated by the people and their stories. That led me to start read the work of Jonathan Edwards, which I found brilliant and deeply challenging.

A considerable amount of research went into this book. How long did it take you to research and write? Did you ever feel overwhelmed by the research?

It took me more than ten years to research and write the book. I had never read Jonathan Edwards before I began work on the book, not even in high school, so I was starting from scratch. I didn’t think I would ever get a handle on why Northampton dismissed him from his pulpit, but I ended up feeling that I had at least a sense of the theological, social and personal issues involved. I really struggled with getting the details and textures of daily life right, until, through the Jonathan Edwards Center, I got access to his will, which listed every item in his household.

I hadn’t realized how frenzied the religious fervor was during the Great Awakening. It almost seems like mass hysteria, which you brought vividly to life. Can you say a little about how you reacted when you learned about the passionate reactions of listeners to the preachers of the movement?

It made so much sense to me that people who lived in such a hierarchical culture would find bodily, emotional and spiritual expression and release in a way that worked within their culture and beliefs.

Guilt seems to be an overwhelming, inescapable burden for the characters in the book. What do you think it was like living with such a dark cloud hanging over one’s daily life?

I have to think about that for a moment. I don’t think of it as guilt so much as a habit of self-searching, of examining one’s own inner life for the inevitable signs of sin. One of the things I find compelling about that is that someone like Jonathan Edwards, who devoted his life to the rigorous pursuit of such a practice, and to pouring his great mental energy and his gifts as a writer and speaker into trying to root out sin, was immersed, along with many others in his culture, in the practice of enslaving other human beings. Despite his efforts, his theology and his brilliance, he missed the sinfulness of that. Still, though, I also see these lives as full of deep joys, including the regular experiences of beauty they found in the sacred, but also within their families and many of their relationships with each other.

Did researching and writing this book affect your own attitudes toward religion and spirituality?

I’m private about my own religious beliefs, but I started from a place of deep respect and a desire to learn as much as I could in order to accurately represent the inner lives of the characters. I ended with deeper knowledge, deeper respect, and ongoing questions.

The story has several point of view characters. Did you have a favorite, and why?

I love them all. I really do. Leah, who was enslaved in the Edwards household, was a great pleasure to write. Writing from the point of view of Elisha Hawley as a boy sneaking out at night to go swimming in the river was one of my favorite moments to be in close with a character. Another was Jonathan Edwards thinking about his wife Sarah’s spiritual experiences in terms of honey, which is a metaphor that comes from him via the Bible.

Insects and nature play an important part as supporting actors in the story, observed by the characters and narrator in minute detail, and sometimes even commenting on the action. Why did you choose to give spiders and beetles and birds their own voices in the story?

There are several reasons. Jonathan Edwards himself used spiders and insects as imagery in his writing, most famously in an image from his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of An Angry God” of God dangling a sinner over the fires of hell as a person might dangle a spider over a hearth fire. Also, I realized during the course of my research that insects would have been very frequently present in the lives of people in eighteenth-century New England, so, in some senses, they came to seem to me to be almost messengers from that other time. Finally, I loved the idea of insect sermons, of spiders and insects preaching back to Jonathan Edwards from their own perspectives.

What was the most surprising thing you learned in your research?

I didn’t know when I started working on a novel inspired by Jonathan Edwards that he had an intimate, lifelong relationship with slavery. It was profoundly surprising.

What’s your current project?

I’ve got a couple of things in mind, but the one I’m working on right now is a novel about Jonathan Edward’s grandmother. That is a wild story.

Thank you, Susan, and good luck with your new project!

For more about Spider in a Tree and Susan’s other books, check out Susan Stinson’s website.

February 27, 2014

History Camp–the Unconference for Local Historians

You’ve heard of unbirthdays. Well, how about an unconference? Basically, an unconference is an event that’s put together by volunteers, is open to anyone, and any participant can propose and create a session. So rather than a conference committee doing all the session planning, the participants create the conference.

On Saturday, March 8, History Camp, the first unconference dedicated to history, will debut in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the IBM Client Center, One Rogers St, (One Charles Park). Scholars, writers, museum professionals, and history lovers of all stripes will present more than twenty sessions on topics ranging from the American Revolution to the Temperance movement, from employment opportunities for history lovers to bringing history into the classroom, from mixing social media and history to the tantalizingly titled “Frenemies and Bromances of the Founding Fathers.”

The event runs from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. and lunch is included. And best of all, it’s free! (Although a small donation of $15 is encouraged to help support the event–or $6 just to pay for lunch. Volunteers are welcome to help with set up and clean up.) Space is limited, but there are still spots open, so check it out!

History Camp registration page

History Camp information page with links to information on presenters and more

February 8, 2014

The Museum of the Early American Circus, Somers, New York

The Museum of the Early American Circus, Somers, NY

When I decided that the characters in my novel Mending Horses were going to join the circus, I very quickly came up with a long list of things I didn’t know. What was a circus like in 1839? What sort of acts might they have? What music did they play? Where did they tour in New England? What did tents and wagons look like?

I sighed in dismay at my research options: the Circus World Museum in Wisconsin and the Ringling Circus Museum in Florida—not exactly day trips for someone living in Massachusetts. Then I found out about the Museum of the Early American Circus in Somers, New York, just a little over two hours away.

This tiny museum is located at the heart of early 19th-century Circus Central. Somers is often referred to as the “Cradle of the American Circus,” and was home to Hacaliah Bailey (1774-1845), who imported the second elephant to the United States in 1805 (the first was imported in 1796). “Old Bet” became the nucleus of a traveling menagerie of exotic animals, and the beginning of a mania for menageries that raged through southwestern New York state in the first half of the 19th century. Pretty soon businessmen in Somers and surrounding towns either joined Bailey as partners or became his competitors.

At first, menageries were more like traveling zoos, quite distinct entities from circuses, with their trick riders and acrobats. But by the late 1830s, the two types of entertainment began to merge into something starting to resemble the circus as we know it today.

Statue of Old Bet at the Museum of the Early American Circus

Hacaliah Bailey prospered, using some of his profits to build the Elephant Hotel at a major crossroads in Somers some time between 1820 and 1825. This grand Federal style hotel, with a statue of Old Bet on its front lawn, is now home to the Somers Historical Society and the Museum of the Early American Circus. Although small, this museum has a phenomenal collection of circus posters and memorabilia, manuscript materials, artifacts, and publications about the early circus. The museum’s curator was kind enough to let me spend several afternoons poring over the collection. You can read the results of my research in Mending Horses.

You can find out more about early menageries and circuses and see some posters and images from the Museum’s collection on their website.

The Museum is open to the public on Memorial and Veteran’s Day and every Thursday, from 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. or by appointment by calling 914-277-4977.