James R. Chiles's Blog, page 7

January 9, 2016

Institutional Memory and the "Silver Tsunami," Part 1

If I had to think of one topic that comes up during every public appearance I make, across all industries and specialties, it's the urgency of replacing the baby boomers now heading for retirement: preserving not just the technical skills, but the memory of what works and what fails.

This story comes to mind. Two months after a wave from the Great Tohoku Earthquake demolished hundreds of towns in northeast Japan, the Washington Post described one that survived: Fudai, a community of 3,000 nestled in a narrow valley that was wide open to the sea. In 1972 its mayor called on the town to build a 51-foot-high floodgate. The project attracted much opposition over the cost ($30 million) and the land required to hold off a big wave -- the next big wave, in the view of then-mayor Kotoku Wamura.

As a young man he'd seen the aftermath of a 1933 tsunami that killed over 400 in Fudai alone. As mayor, he led the project and faced a lot of hostile questions: Why did the town need it? Why so high? Other Japanese cities had put up gates and seawalls, but none were so high. How could Fudai pay for it?

Wamura was undaunted. A good thing, too: When that next wave arrived on March 11, 2011, water lapped over the top but the damage was inconsequential; the only death was one man who had climbed over to check on his fishing boat. Without Wamura's big wall, Fudai would have been reduced to bodies, trash, and rubble. Again.

Memory – vivid and awful – carried Fudai's floodgate project forward against all opposition. It needed more than the mayor's individual memory: it was a collective memory of everybody old enough to have seen the effects of the 1933 wave.

The subject of memory and how to hold onto it is a hot topic because the baby boomers aren't babies anymore. Experts warn that the looming retirements, across all sectors of the economy, is a “silver-haired tsunami.”

However much fifty- and sixty-somethings look forward to retirement, they're equally eager for anti-Alzheimer nostrums, whether vitamin packets, red wine, Soduku puzzles, or online memory tests. Worries over memories that slip-side away extends to the largest scale. Consultants are wagging their fingers at companies and agencies like NASA, warning them to capture their “institutional memory” with extended videotape interviews and copious databases.

They're referring to the unwritten knowledge held by skilled workers, seen-it-all foremen, and hands-on managers. It's trouble-shooting. It's the agility that strikes a balance between handling existing projects and taking on new challenges as conditions change. In short, it's the know-how that gets things done and heads off the ICE, the Imminent Catastrophic Event.

Before looking into what collective memory is, let's think about individual memory. While our brains are sometimes compared to a computer's storage banks, people are radically different from computers in how they collect and store information. In 1861 Abe Lincoln referred to the mystic chords of memory, and he wasn't far off the mark. Memory is not a predictable set of nerve connections. We know more about how it goes away than why it stays.

Experts in mnemonic techniques assure us that with training and jaw-aching concentration just about anybody can erect a memory palace in their minds and then wow their friends by quickly memorizing the order of an entire, shuffled deck of cards. Meanwhile, most of us still have not a memory palace but something more like a drafty house. Even without the affliction of Alzheimer's, facts blow out the back door when we're not looking, and other facts get mixed up like old keys tossed into junk drawers. Check out this “Jaywalking” episode from Leno, for a wacky stroll through history as feebly recalled by the man on the street.

The good news is that humans are, or can be, quite good at building and holding a body of knowledge. Knowledge is what drives our decisions. It's a combination of skills, recalled facts, and insights, and is unique to each person.

Recall my drafty-memory-house analogy? Now imagine a snug, warm greenhouse in the back yard, a place for plants to grow and thrive. For an amazing example of how people can amass huge bodies of knowledge when they must, check out Mark Twain's Life on the Mississippi.

He describes how each licensed pilot of the 1850s had to know the channels suitable for big steamboats along more than a thousand miles of unmarked river, storing the images for use by day, night, and in the fog … and then absorb new information as channels, snags, and sandbars changed.

Such vast collections fit into a few pounds of brain tissue because they're braced and motivated by personal experiences, vivid stories from trusted sources, reading, and certification courses.

That's memory and knowledge at the micro level. What about macro: Can an entire company, or even the workers across a single plant, share a “collective memory”? Safety expert Trevor Kletz, author of What Went Wrong? and Still Going Wrong, believed so.

The tendency of refinery and chemical plants to lose their institutional memory of past disasters, about every ten to fifteen years, has been a concern in the chemical-processing safety literature for years. Writing in Modern Railways, Roger Ford said that accidents happen “when the last man who remembers the previous disaster retires.”

On the other side of the memory-is-good question are advocates of extreme makeover, corporate style. If what Robert McMath calls Corporate Alzheimer's is the collateral damage, so what? To these skeptics, it doesn't matter whether anybody in the organization recalls past problems and how to avoid them, because the key is going forward. Here are their arguments:

Didn't the fabulously successful Henry Ford say in 1916, “History is more or less bunk.... We don't want tradition. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history we make today.”

Here's how Ford's thinking lives on:

“All damage and injuries are due to either (1) unpredictable flukes of fate, never to be repeated and therefore needing no attention, or (2) errors by low-ranking workers who recklessly flaunted their training and operating manuals. So there's nothing to learn.”“Internal histories that capture damage incidents, close calls, and lessons learned would be expensive to assemble, and then plaintfiffs' lawyers might get hold of it, so why go to the trouble? It's better to plead ignorance after the next bad headline, and do it convincingly.”

Now for the other side of the coin. There's a museum called The Collection at New Product Works of Ann Arbor, Michigan, for which people pay a lot of money to tour. The shelves hold more than a hundred thousand products, most of which you can't find anywhere else because they flopped so quickly, like Look of Buttermilk shampoo, Male Chauvinist Aftershave, and a urine-colored bottled tea called “Tea Whiz.”

Even the museum at Ann Arbor, big as it is, can't display all the ways that firms and governments forget at least as much stuff as we mere humans do. And about as fast.

The problems of rapid employee loss and turnover are magnified by the loss of supervisors with long and plant-specific experience.It's been said that foremen and supervisors act like synapses of our brains. On the job, they link individuals into functional units that span the organizational charts; along with motivated higher-ups, they can press for prompt action to head off a disaster. Critics like Kevin Foster call the discharge of such experts not downsizing but dumbsizing. But the nation would still have a memory drain problem even if companies reversed direction, because there's a graying workforce that is sure to move on sooner rather than later. Mack Truck built an assembly plant for the Soviet Union, but when the opportunity came to win a contract to refurbish the facility in Russia, Mack lost the bid to another company because the company experts on the original plant had moved on and no working memory remained of how, or why, the truck plant was laid out.

A plant doesn't have to be halfway around the world to turn into something dangerously unfamiliar, as employees change jobs and memories fade. Disaster annals are full of spectacular events triggered after an incoming worker looks at some pre-existing gizmo, decides it's getting in his way or slowing him down, and changes it without asking anybody. This can be a enormous hazard at an oil refinery, where an peculiar-looking vent stack might be essential to avoiding a vacuum that would cause two chemicals to react and mix at the wrong time. In a perfect world, a complete set of plans would not only show the machine in its actual, “as built, as modified” status, it would also have little tags explaining what the tubes and safety valves in a boiler room or refinery are there for, in case someone has the hankering to tinker.

==

How to forge collective memory that leads to safer operations? That's the subject of Part 2.

This story comes to mind. Two months after a wave from the Great Tohoku Earthquake demolished hundreds of towns in northeast Japan, the Washington Post described one that survived: Fudai, a community of 3,000 nestled in a narrow valley that was wide open to the sea. In 1972 its mayor called on the town to build a 51-foot-high floodgate. The project attracted much opposition over the cost ($30 million) and the land required to hold off a big wave -- the next big wave, in the view of then-mayor Kotoku Wamura.

As a young man he'd seen the aftermath of a 1933 tsunami that killed over 400 in Fudai alone. As mayor, he led the project and faced a lot of hostile questions: Why did the town need it? Why so high? Other Japanese cities had put up gates and seawalls, but none were so high. How could Fudai pay for it?

Wamura was undaunted. A good thing, too: When that next wave arrived on March 11, 2011, water lapped over the top but the damage was inconsequential; the only death was one man who had climbed over to check on his fishing boat. Without Wamura's big wall, Fudai would have been reduced to bodies, trash, and rubble. Again.

Memory – vivid and awful – carried Fudai's floodgate project forward against all opposition. It needed more than the mayor's individual memory: it was a collective memory of everybody old enough to have seen the effects of the 1933 wave.

The subject of memory and how to hold onto it is a hot topic because the baby boomers aren't babies anymore. Experts warn that the looming retirements, across all sectors of the economy, is a “silver-haired tsunami.”

However much fifty- and sixty-somethings look forward to retirement, they're equally eager for anti-Alzheimer nostrums, whether vitamin packets, red wine, Soduku puzzles, or online memory tests. Worries over memories that slip-side away extends to the largest scale. Consultants are wagging their fingers at companies and agencies like NASA, warning them to capture their “institutional memory” with extended videotape interviews and copious databases.

They're referring to the unwritten knowledge held by skilled workers, seen-it-all foremen, and hands-on managers. It's trouble-shooting. It's the agility that strikes a balance between handling existing projects and taking on new challenges as conditions change. In short, it's the know-how that gets things done and heads off the ICE, the Imminent Catastrophic Event.

Before looking into what collective memory is, let's think about individual memory. While our brains are sometimes compared to a computer's storage banks, people are radically different from computers in how they collect and store information. In 1861 Abe Lincoln referred to the mystic chords of memory, and he wasn't far off the mark. Memory is not a predictable set of nerve connections. We know more about how it goes away than why it stays.

Experts in mnemonic techniques assure us that with training and jaw-aching concentration just about anybody can erect a memory palace in their minds and then wow their friends by quickly memorizing the order of an entire, shuffled deck of cards. Meanwhile, most of us still have not a memory palace but something more like a drafty house. Even without the affliction of Alzheimer's, facts blow out the back door when we're not looking, and other facts get mixed up like old keys tossed into junk drawers. Check out this “Jaywalking” episode from Leno, for a wacky stroll through history as feebly recalled by the man on the street.

The good news is that humans are, or can be, quite good at building and holding a body of knowledge. Knowledge is what drives our decisions. It's a combination of skills, recalled facts, and insights, and is unique to each person.

Recall my drafty-memory-house analogy? Now imagine a snug, warm greenhouse in the back yard, a place for plants to grow and thrive. For an amazing example of how people can amass huge bodies of knowledge when they must, check out Mark Twain's Life on the Mississippi.

He describes how each licensed pilot of the 1850s had to know the channels suitable for big steamboats along more than a thousand miles of unmarked river, storing the images for use by day, night, and in the fog … and then absorb new information as channels, snags, and sandbars changed.

Such vast collections fit into a few pounds of brain tissue because they're braced and motivated by personal experiences, vivid stories from trusted sources, reading, and certification courses.

That's memory and knowledge at the micro level. What about macro: Can an entire company, or even the workers across a single plant, share a “collective memory”? Safety expert Trevor Kletz, author of What Went Wrong? and Still Going Wrong, believed so.

The tendency of refinery and chemical plants to lose their institutional memory of past disasters, about every ten to fifteen years, has been a concern in the chemical-processing safety literature for years. Writing in Modern Railways, Roger Ford said that accidents happen “when the last man who remembers the previous disaster retires.”

On the other side of the memory-is-good question are advocates of extreme makeover, corporate style. If what Robert McMath calls Corporate Alzheimer's is the collateral damage, so what? To these skeptics, it doesn't matter whether anybody in the organization recalls past problems and how to avoid them, because the key is going forward. Here are their arguments:

Didn't the fabulously successful Henry Ford say in 1916, “History is more or less bunk.... We don't want tradition. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history we make today.”

Here's how Ford's thinking lives on:

“All damage and injuries are due to either (1) unpredictable flukes of fate, never to be repeated and therefore needing no attention, or (2) errors by low-ranking workers who recklessly flaunted their training and operating manuals. So there's nothing to learn.”“Internal histories that capture damage incidents, close calls, and lessons learned would be expensive to assemble, and then plaintfiffs' lawyers might get hold of it, so why go to the trouble? It's better to plead ignorance after the next bad headline, and do it convincingly.”

Now for the other side of the coin. There's a museum called The Collection at New Product Works of Ann Arbor, Michigan, for which people pay a lot of money to tour. The shelves hold more than a hundred thousand products, most of which you can't find anywhere else because they flopped so quickly, like Look of Buttermilk shampoo, Male Chauvinist Aftershave, and a urine-colored bottled tea called “Tea Whiz.”

Even the museum at Ann Arbor, big as it is, can't display all the ways that firms and governments forget at least as much stuff as we mere humans do. And about as fast.

The problems of rapid employee loss and turnover are magnified by the loss of supervisors with long and plant-specific experience.It's been said that foremen and supervisors act like synapses of our brains. On the job, they link individuals into functional units that span the organizational charts; along with motivated higher-ups, they can press for prompt action to head off a disaster. Critics like Kevin Foster call the discharge of such experts not downsizing but dumbsizing. But the nation would still have a memory drain problem even if companies reversed direction, because there's a graying workforce that is sure to move on sooner rather than later. Mack Truck built an assembly plant for the Soviet Union, but when the opportunity came to win a contract to refurbish the facility in Russia, Mack lost the bid to another company because the company experts on the original plant had moved on and no working memory remained of how, or why, the truck plant was laid out.

A plant doesn't have to be halfway around the world to turn into something dangerously unfamiliar, as employees change jobs and memories fade. Disaster annals are full of spectacular events triggered after an incoming worker looks at some pre-existing gizmo, decides it's getting in his way or slowing him down, and changes it without asking anybody. This can be a enormous hazard at an oil refinery, where an peculiar-looking vent stack might be essential to avoiding a vacuum that would cause two chemicals to react and mix at the wrong time. In a perfect world, a complete set of plans would not only show the machine in its actual, “as built, as modified” status, it would also have little tags explaining what the tubes and safety valves in a boiler room or refinery are there for, in case someone has the hankering to tinker.

==

How to forge collective memory that leads to safer operations? That's the subject of Part 2.

Published on January 09, 2016 13:49

December 16, 2015

What's It Like to Interview Harrison Ford?

Pretty interesting! He's got a straightforward style, and lets you know right away whether he thinks the question is worth answering. While researching my helicopter book

The God Machine

, I thought it would be good to get a high-profile user's view of the machines, which are expensive to buy and operate. Ford is among a few thousand private owners who can afford it. (Photo, CBS News)

It took six months of back-and-forthing with his executive assistant at HF Productions, but in time we scheduled a half-hour talk. Ford was running early that morning so he called my cellphone to change the time, leaving a voicemail message, which (of course!) I saved.

The subject was strictly helicopters; nary a movie in sight. He talked about his training, his checkride in a Bell, and what it was like to fly out of the notoriously challenging 60th Street Heliport in Manhattan. “Now it's shut down and that’s a good thing,” he said, comparing it to flying in and out of a box with one open side. “When you came out, you were facing an unknown wind, but the wind was usually along the East River, out of the south to the north. It usually needed an immediate pedal turn upon lifting up.”

Being a superstar, while flying cross country, did he feel he could land his Bell 407 just about any vacant field where it would fit, such as near a roadside diner? No, he said, “I don’t do unplanned back-lot landings, because I don’t know the municipal attitude. They all have to have a say in helicopter landings. Plus, I’m getting fuel along the way so I’m stopping at airports.”

I asked him about his favorite times in a helicopter, “Probably mountain flying in Wyoming,” he replied, referring to his volunteer work around Jackson Hole. “One of the more critical flying tasks was helping the mountain rangers pick up their winter stashes of equipment. Density altitude is a factor, because of the height, and also it’s warm by then. It’s pretty technical flying. You get a couple of big guys in there, each 200 lb, and 250 lb of gear. … This is just above the tree line. So it’s a matter of beoing able to pick it up and drop it over a convenient edge – you have to fly down before you can fly up, that kind of situation. Yes, that means setting down pretty close to a dropoff.”

He also enjoyed flying a tiltrotor at the Bell factory. “It's an incredible machine – you tilt the nacelles over and you take off like a drag racer.”

Emergency procedures? He estimated that he'd done 200 “full down” autorotation practices, with a freewheeling main rotor, and the machine gliding all the way to the ground. “I go to the Bell school once or twice a year and they really train you in emergency procedures,” he said. “They’ll have you do twenty-five autorotations in a day.”

During practice in Southern California in 1999 the helicopter he was flying with an instructor hit hard and turned over in a dry riverbed. “We were in a [Bell] 206 at the bottom of autorotation [anticipating only doing an autorotation to power recovery] but when we rolled the power in, there was no response. It kept going down. This area is a helicopter practice area but it has coarse sand, and there are a lot of snags.”

I mentioned that some helicopter pilots never do any autorotation practices all the way to the ground, because their schools consider it too dangerous. “Well,” he said in a voice that sounded just like Han Solo's, “assuming engines won’t ever quit, that’s not a good idea.”

“There’s all kind of helicopter traps out there – you’ve got to stay alert.”

It took six months of back-and-forthing with his executive assistant at HF Productions, but in time we scheduled a half-hour talk. Ford was running early that morning so he called my cellphone to change the time, leaving a voicemail message, which (of course!) I saved.

The subject was strictly helicopters; nary a movie in sight. He talked about his training, his checkride in a Bell, and what it was like to fly out of the notoriously challenging 60th Street Heliport in Manhattan. “Now it's shut down and that’s a good thing,” he said, comparing it to flying in and out of a box with one open side. “When you came out, you were facing an unknown wind, but the wind was usually along the East River, out of the south to the north. It usually needed an immediate pedal turn upon lifting up.”

Being a superstar, while flying cross country, did he feel he could land his Bell 407 just about any vacant field where it would fit, such as near a roadside diner? No, he said, “I don’t do unplanned back-lot landings, because I don’t know the municipal attitude. They all have to have a say in helicopter landings. Plus, I’m getting fuel along the way so I’m stopping at airports.”

I asked him about his favorite times in a helicopter, “Probably mountain flying in Wyoming,” he replied, referring to his volunteer work around Jackson Hole. “One of the more critical flying tasks was helping the mountain rangers pick up their winter stashes of equipment. Density altitude is a factor, because of the height, and also it’s warm by then. It’s pretty technical flying. You get a couple of big guys in there, each 200 lb, and 250 lb of gear. … This is just above the tree line. So it’s a matter of beoing able to pick it up and drop it over a convenient edge – you have to fly down before you can fly up, that kind of situation. Yes, that means setting down pretty close to a dropoff.”

He also enjoyed flying a tiltrotor at the Bell factory. “It's an incredible machine – you tilt the nacelles over and you take off like a drag racer.”

Emergency procedures? He estimated that he'd done 200 “full down” autorotation practices, with a freewheeling main rotor, and the machine gliding all the way to the ground. “I go to the Bell school once or twice a year and they really train you in emergency procedures,” he said. “They’ll have you do twenty-five autorotations in a day.”

During practice in Southern California in 1999 the helicopter he was flying with an instructor hit hard and turned over in a dry riverbed. “We were in a [Bell] 206 at the bottom of autorotation [anticipating only doing an autorotation to power recovery] but when we rolled the power in, there was no response. It kept going down. This area is a helicopter practice area but it has coarse sand, and there are a lot of snags.”

I mentioned that some helicopter pilots never do any autorotation practices all the way to the ground, because their schools consider it too dangerous. “Well,” he said in a voice that sounded just like Han Solo's, “assuming engines won’t ever quit, that’s not a good idea.”

“There’s all kind of helicopter traps out there – you’ve got to stay alert.”

Published on December 16, 2015 18:24

November 21, 2015

Obscure Lingo from the Machine Frontier

Back from my 42nd public-speaking gig. The one this week was in Miami, doing a keynote for a congress of the forensic engineering division of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

While there I added to my collection of trade lingo, accumulated during more than three decades of research into the machine frontier. This first one is from the Miami conference, and was new to me:

Spike-killed ties: These are cross ties in railroad tracks in which the spikes have worked loose, and have been pounded back in repeatedly. After so many times, the wood is weak and the tie has lost its grip. Spike-killed ties are bad because they lead to wide-gauge derailments.

Blue line: This is what USAF mission planners call the path that pilots of low-observable (aka stealth) aircraft are supposed to follow while in enemy airspace. The idea is to travel where the radar fence is weak, wherever possible. As all geeks should know, stealthy aircraft aren't "invisible" to radar; they're just hard to pick up. The best route is one where the airplane is lost in the noise, and only resolved for brief intervals, if at all.

Iron roughneck: Automated tool to attach, and detach, sections of a drill string on an oil rig. This substitutes for human roughnecks who relied on tongs and chains.

Rabbit tool: Small hydraulic device used by firefighters to force open steel doors in steel frames.

Burning bar, aka thermic lance: Pipe filled with metal rods, fed by oxygen at the operator's end. Once ignited at the other end the metal burns at a very high temperature. The flame will burn through any substance in its way, including diamond. Here's a video:

Dead leg: A section of pipe that's been left behind, supposedly sealed, after work in a complicated set of piping, typically a refinery or chemical plant. According to the Chemical Safety Board, dead legs can be dangerous because they increase the chances for pipe breaks.

Alarm storm: A wave of automated alarms when a bunch of things going wrong at once. I've heard it used among power-plant operators and surgeons.

Gin pole: A derrick-like framework that tower builders use. It's installed temporarily on the mast. Because it's massive enough to bring the whole tower down in a collision, they take extra care whenever moving it.

Jesus nut: A Vietnam-era term for a fastener at the top of the rotor mast in Huey and Cobra helicopters.

Battle short: A desperate measure in the Navy during combat, in which safeties are bypassed to save the ship, say, overriding a reactor scram.

While there I added to my collection of trade lingo, accumulated during more than three decades of research into the machine frontier. This first one is from the Miami conference, and was new to me:

Spike-killed ties: These are cross ties in railroad tracks in which the spikes have worked loose, and have been pounded back in repeatedly. After so many times, the wood is weak and the tie has lost its grip. Spike-killed ties are bad because they lead to wide-gauge derailments.

Blue line: This is what USAF mission planners call the path that pilots of low-observable (aka stealth) aircraft are supposed to follow while in enemy airspace. The idea is to travel where the radar fence is weak, wherever possible. As all geeks should know, stealthy aircraft aren't "invisible" to radar; they're just hard to pick up. The best route is one where the airplane is lost in the noise, and only resolved for brief intervals, if at all.

Iron roughneck: Automated tool to attach, and detach, sections of a drill string on an oil rig. This substitutes for human roughnecks who relied on tongs and chains.

Rabbit tool: Small hydraulic device used by firefighters to force open steel doors in steel frames.

Burning bar, aka thermic lance: Pipe filled with metal rods, fed by oxygen at the operator's end. Once ignited at the other end the metal burns at a very high temperature. The flame will burn through any substance in its way, including diamond. Here's a video:

Dead leg: A section of pipe that's been left behind, supposedly sealed, after work in a complicated set of piping, typically a refinery or chemical plant. According to the Chemical Safety Board, dead legs can be dangerous because they increase the chances for pipe breaks.

Alarm storm: A wave of automated alarms when a bunch of things going wrong at once. I've heard it used among power-plant operators and surgeons.

Gin pole: A derrick-like framework that tower builders use. It's installed temporarily on the mast. Because it's massive enough to bring the whole tower down in a collision, they take extra care whenever moving it.

Jesus nut: A Vietnam-era term for a fastener at the top of the rotor mast in Huey and Cobra helicopters.

Battle short: A desperate measure in the Navy during combat, in which safeties are bypassed to save the ship, say, overriding a reactor scram.

Published on November 21, 2015 14:26

November 12, 2015

Light a Candle for the 50th Anniversary of the Northeast Blackout

Following is the first section of my article on how the big blackouts of 1965 and 1977 came about (photo credit, The Guardian).

It was the first time I wrote about a system so complex that no single person could stay on top of it. That realization laid the foundation for Inviting Disaster later.

The rest of the feature can be accessed at the Invention & Technology issue archive.

Learning from the Big Blackouts

Two nights of darkness, in 1965 and 1977, showed how fragile the nation’s power system could be

James R. Chiles

Fall 1985 | Volume 1, Issue 2

Normally night spreads from east to west with the rotation of the earth, but the evening of November 9, 1965, was different. Darkness also spread from north to south. Southern Ontario went dark first, much of New York State a few seconds later, then most of New England, and finally New York City. By 5:28 P.M., thirty million people were stumbling toward any light available. Subways stopped and furnaces chilled, and America briefly lost one-fifth of its electricity. What was the cause? Maybe a generator failure, maybe sabotage—for several awkward days no one knew.

America’s electric-power network is so vast that solar flares affect it and so convoluted that the start-up of one generator affects others thousands of miles away. It is perhaps our most complex technology. But the 1965 blackout—and others that have followed—taught that complexity does not equal sophistication.

In the twenty years since that catastrophe, power companies have been working with mixed success to prevent more outages. Transmission lines have greater capacity now, control centers are more computerized and hold tighter reins over power flows, utilities cooperate and share more information, generating stations have emergency power to restart generators thrown off the grid by electrical jolts, and operating procedures have been revamped. Still, major outages happen every year, benighting thousands and occasionally, as in New York in 1977, millions of people, but many in the industry are confident that another 1965-scale blackout is unlikely.

Smaller blackouts can be costly too, though, and some observers fear that the stability of the network is threatened by certain utilities’ financial problems and by economic pressure to move electricity long distances from power-rich areas to utilities dependent on oil-fired power plants. In parts of the country, such long-distance purchases of economy power are pushing transmission lines to the limits of safety by straining their capacity.

In 1965 the utility industry was about eighty years old. America’s first central power station had started supplying a small district of Manhattan in 1882. The idea didn’t catch on for several years because building owners could provide for themselves more cheaply by buying generators and putting them in basements. But the price of central service dropped by 1886, and the new electric streetcars were increasing daytime demand dramatically. The same advantages of reliability and savings that then led isolated users to join in a central system also persuaded utilities to link with one another once high-voltage alternating-current equipment was available.

Regional grids started forming: the Pacific states, the Southwest, the Southeast, and the Upper Midwest. The first big interconnection in New England came about in 1913 because the utility at Turners Falls, Massachusetts, had a surplus of cheap hydroelectric power to sell. Interconnections multiplied rapidly across the Northeast during World War I, when defense plants needed power in amounts that isolated utilities could not supply. In 1959 Ontario Hydro joined the Northeast Interconnection, which then changed its name to Canada-United States Eastern Interconnection and acquired the acronym CANUSE.

November 9, 1965, was—until the blackout—an ordinary day. From New York City on the southern end of CANUSE to Ontario in the north, the weather was clear and cool. As the sun dropped, lights went on. Power stations all over the Eastern Interconnected System—CANUSE and the other big systems it was connected to—opened water and fuel valves to meet the need.

One of these was the Sir Adam Beck No. 2 hydroelectric plant, set on the Canadian cliffs near Niagara Falls. Most of its output was going west and north to Toronto, across Lake Ontario. The Beck plant was working a bit harder than usual because the Lakeview power station near Toronto was having problems with its machinery. The load on Beck’s transmission lines reached the point at which an obscure relay, installed in 1951 and last adjusted in 1963, ordered a circuit breaker to disconnect one line. This started a chain of events that no one could have predicted exactly, because alternating current finds its own pathways through the multitude of combinations possible in a large power network, which is itself changing every minute. At 5:16 and eleven seconds, the system began to move with frightening speed.

When the Beck relay ordered the first westbound transmission line cut off, 375 million watts of power crowded onto the four other westbound lines. In less than three seconds they tripped out in turn, and at least 1.5 billion watts rushed into America across two other lines strung over the Niagara River. The surge of electricity tried to reenter Canada at the Massena, New York, interconnection, but that interconnection overloaded, and the surplus power turned south, down the backbone of the CANUSE transmission system.

Relays interpreted the power surge as a short circuit and started signaling circuit breakers to separate the system into islands. Shuddering under the impact of all these circuit breakers and the wildly fluctuating current, generators slowly fell out of the sixty-cycle-per-second, threephase lockstep that the alternating-current networks demanded. One island, which took in southeast New York State, New York City, and much of New England, was suddenly short of generation capacity, with a severe deficit in the northern end pulling great pulses of power from the south. The deficit grew as the electrical chaos forced generators off the network.

Continued here

Published on November 12, 2015 15:22

October 16, 2015

How to Park Your Super-Crane

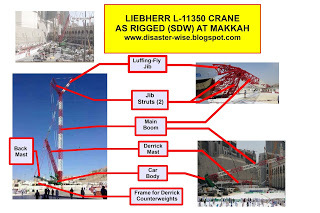

People who are following news connected to the destruction caused by the Liebherr L11350 super-crane that fell backward at the Grand Mosque in Makkah, KSA, may have wondered what such a crane would have looked like had the contractor (Saudi Binladin Group) stowed the machine in case of bad weather, as directed by the manufacturer.

So here's a photo of what this particular model looks like when safed. Except for the lack of a back mast to the detached counterweight, this Liebherr L11350 is rigged similarly to the crane at Makkah, which was an "SDW" arrangement (Photo, Mace Ltd):

The thin, red and white structure on the far left is the luffing-fly jib, labeled in my previous post and diagram. Its latticed counterpart on the right side is the derrick mast.

Normally the jib would be way up in the air, topping the boom, but it can be angled down with winches and pulleys that allow the jib angle to be changed (in crane language, "luffed") from the operator's seat - in this case, pointed so far down that the tip of the jib touches the ground.

We don't know why the crane parked on the plaza by the Massa wasn't routinely parked this way. Lowering the boom and jib might have needed restoration of counterweights that had been removed, along with the need to round up operators and riggers rated to use this machine. Maybe bringing the jib to the ground would have interfered with pedestrian traffic. In general, I'm guessing, it seemed easier to leave the main boom and jib at a near-vertical angle.

But easy doesn't mean safe, as I wrote in Inviting Disaster.

If there's interest I'll post on the amazing, if narrow, niche of super-cranes.

So here's a photo of what this particular model looks like when safed. Except for the lack of a back mast to the detached counterweight, this Liebherr L11350 is rigged similarly to the crane at Makkah, which was an "SDW" arrangement (Photo, Mace Ltd):

The thin, red and white structure on the far left is the luffing-fly jib, labeled in my previous post and diagram. Its latticed counterpart on the right side is the derrick mast.

Normally the jib would be way up in the air, topping the boom, but it can be angled down with winches and pulleys that allow the jib angle to be changed (in crane language, "luffed") from the operator's seat - in this case, pointed so far down that the tip of the jib touches the ground.

We don't know why the crane parked on the plaza by the Massa wasn't routinely parked this way. Lowering the boom and jib might have needed restoration of counterweights that had been removed, along with the need to round up operators and riggers rated to use this machine. Maybe bringing the jib to the ground would have interfered with pedestrian traffic. In general, I'm guessing, it seemed easier to leave the main boom and jib at a near-vertical angle.

But easy doesn't mean safe, as I wrote in Inviting Disaster.

If there's interest I'll post on the amazing, if narrow, niche of super-cranes.

Published on October 16, 2015 18:33

October 10, 2015

Best in Class: Precision hoist work with helicopters

Passing along this video of a helicopter crew and riggers assembling a tower atop the Incity skyscraper in Lyons, France, by raising sections on a long cable:

Whether it's short-lining or long-lining, moving external loads by cable takes extraordinary skill: to pilot the helicopter while looking far below, to keep the load from swinging and then to set the load within an inch or two of the desired spot, and to avoid tangling or hitting things along the way.

While researching The God Machine I heard many stories of pilots who brought themselves down while carrying loads on cables.

One of the striking sidelights in the helicopter world is that pilots have the authority to punch off a cable-slung load if they are sure it is going to cause the helicopter to crash: not a happy ending, particularly if there's a person on the end of the cable.

Whether it's short-lining or long-lining, moving external loads by cable takes extraordinary skill: to pilot the helicopter while looking far below, to keep the load from swinging and then to set the load within an inch or two of the desired spot, and to avoid tangling or hitting things along the way.

While researching The God Machine I heard many stories of pilots who brought themselves down while carrying loads on cables.

One of the striking sidelights in the helicopter world is that pilots have the authority to punch off a cable-slung load if they are sure it is going to cause the helicopter to crash: not a happy ending, particularly if there's a person on the end of the cable.

Published on October 10, 2015 18:34

October 7, 2015

More on Dreamception: A simply amazing app

Following up on my thumbs-up report about the Dreamception iOS app when applied to ice photos ... Here's a before-and-after, with new Dreamception output on the right (in low resolution, here):

There are a lot of permutations given all the filters available, and the exact combination has a lot to do with whether the images are interesting or just flukey.

There are a lot of permutations given all the filters available, and the exact combination has a lot to do with whether the images are interesting or just flukey.

Published on October 07, 2015 18:52

October 5, 2015

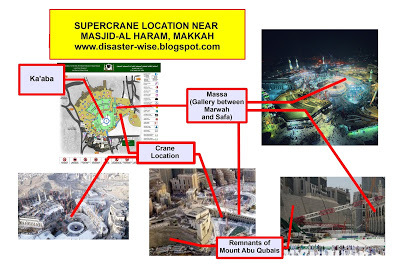

Crane Down at Masjid al-Haram, September 11

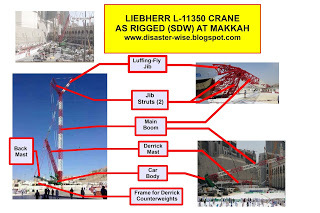

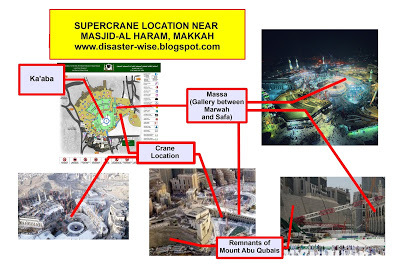

About the crane disaster last month in Makkah (Mecca in its westernized spelling). A Liebherr L-11350 crawler crane tipped backward in a windstorm, killing 109 people in what forensic folks call the laydown zone. The worst area of destruction was where the 100-ton mast and jib dropped on the roof of a very long building on the east side called the Massa. The upper end of the jib crashed onto pedestrian areas on the other side of this building (photo AFP)

When the crawler crane fell over it also came close to destroying a tower crane, a Liebherr 335, also located on the east side of the Massa.

Here's how the roof damage looked:

The "W"-shaped object above the Massa roof, projecting into it, is where the two jib struts join up with the upper end of the main boom, and the lower end of the jib (see below for a diagram). The jib struts provide a support for the jib. As the crane fell over backward, the two jib struts acted like twin piledrivers, smashing into the third and second floors of the Massa.

Here's a link to the only public video I've seen of the crane going down (but I'm sure the Saudis have a lot of CCTV footage):

Here's a diagram of the basic components, before and after:

How big was it? As this crane was rigged (called an SDW arrangement in the manual), the tip of the L-11350's upper structure called the "luffing-fly jib") reached more than 600 feet off the ground.

It's classed as a super-crane: while not the world's biggest crawler crane, it's close. The lift capacity under ideal conditions is 1,350 metric tons. It's a popular crane for refinery turnarounds and wind-farm projects.

How long had it been on the plaza? More than three years. It was part of a big Saudi purchase from Liebherr in 2012.

What was the crane doing there? It had been parked and inactive for some time. Details on usage are fuzzy; given past photos taken by pilgrims and posted online, the crane hadn't gotten much use lately. We're told that it was to be used again after the September 2015 Hajj, as part of ongoing expansion of the Masjid al-Haram and the Massa in particular. Here's a diagram of the location.

What do the initial reports say? Authorities have been interrogating employees of the contractor, Saudi Binladin Group, which has filed an insurance claim. While this particular windstorm was unusually powerful, the crane manufacturer says it was a mistake to park the crane with its boom at such a high angle (85 degrees), where it could catch the wind.

What about the cleanup? Because the 2015 Hajj pilgrimage was to begin less than two weeks after the wreck, work went on around the clock. Experts decided structural damage to the plaza at the base of the crane was so severe that the removal of the lower chassis (called the car body) would have to wait until after the Hajj, so this area was screened off from pilgrims.

The focus was on removing the main boom and derrick mast from above the eastern plaza, and pulling the jib and jib struts off the roof -- and without causing more damage to the Massa, which is heavily used by pilgrims.

If there's interest I'll post on how a team from Aramco got this done, with advice from heavy-life expert Mammoet, which I mentioned in this post about strand jacks.

When the crawler crane fell over it also came close to destroying a tower crane, a Liebherr 335, also located on the east side of the Massa.

Here's how the roof damage looked:

The "W"-shaped object above the Massa roof, projecting into it, is where the two jib struts join up with the upper end of the main boom, and the lower end of the jib (see below for a diagram). The jib struts provide a support for the jib. As the crane fell over backward, the two jib struts acted like twin piledrivers, smashing into the third and second floors of the Massa.

Here's a link to the only public video I've seen of the crane going down (but I'm sure the Saudis have a lot of CCTV footage):

Here's a diagram of the basic components, before and after:

How big was it? As this crane was rigged (called an SDW arrangement in the manual), the tip of the L-11350's upper structure called the "luffing-fly jib") reached more than 600 feet off the ground.

It's classed as a super-crane: while not the world's biggest crawler crane, it's close. The lift capacity under ideal conditions is 1,350 metric tons. It's a popular crane for refinery turnarounds and wind-farm projects.

How long had it been on the plaza? More than three years. It was part of a big Saudi purchase from Liebherr in 2012.

What was the crane doing there? It had been parked and inactive for some time. Details on usage are fuzzy; given past photos taken by pilgrims and posted online, the crane hadn't gotten much use lately. We're told that it was to be used again after the September 2015 Hajj, as part of ongoing expansion of the Masjid al-Haram and the Massa in particular. Here's a diagram of the location.

What do the initial reports say? Authorities have been interrogating employees of the contractor, Saudi Binladin Group, which has filed an insurance claim. While this particular windstorm was unusually powerful, the crane manufacturer says it was a mistake to park the crane with its boom at such a high angle (85 degrees), where it could catch the wind.

What about the cleanup? Because the 2015 Hajj pilgrimage was to begin less than two weeks after the wreck, work went on around the clock. Experts decided structural damage to the plaza at the base of the crane was so severe that the removal of the lower chassis (called the car body) would have to wait until after the Hajj, so this area was screened off from pilgrims.

The focus was on removing the main boom and derrick mast from above the eastern plaza, and pulling the jib and jib struts off the roof -- and without causing more damage to the Massa, which is heavily used by pilgrims.

If there's interest I'll post on how a team from Aramco got this done, with advice from heavy-life expert Mammoet, which I mentioned in this post about strand jacks.

Published on October 05, 2015 20:23

September 20, 2015

DeepDreaming with Ice Photography

Will be posting an infographic on the Sept. 11 Mecca supercrane disaster soon; meantime, on a lighter subject, here's a note on what I'm doing with my stock of macro-ice photos.

As followers may know from my Interstellar fan poster, ice photos taken with a macro lens can have an uncanny aspect, suggesting something not quite of Earth. So when I heard about DreamCeption for IoS, that sounded like something I should check out.

Sure enough: here's an example of patterns that Dreamception added to one of my ice photos, Fire Cave:

That's at low-resolution. Here's a sample of what Dreamception can do at a higher resolution, from a small portion of the upper right of the image:

That's impressive for the consumer market. The processing load must be substantial, which is why it runs in the cloud on supercomputers.

The app's based on earlier work at Google, originally set up so that its artificial-intelligence program, called DeepDream, could recognize elements of photos, say, distinguishing a dog from a doghouse. Turns out that DeepDream can work the other way, superimposing details onto photos in a search for patterns and meaning. Filters such as "afterlife" impose buildings, faces, and all kinds of crazy things on ice photos:

Using the Dreamception app on an iPad is easy -- just upload an image from your Camera Roll folder, select a filter, hit submit, then save back to the Camera Roll. It's possible to process an image with one filter and then apply another filter to that result.

After some experimenting, I think the most striking results come that way, from using the filters in series. For higher resolution you may have to break your image into pieces and recombine the Dreamception output with a graphics app, such as one of my faves, ProCreate.

ProCreate's layer tool is also a good way to restore some of your original image, in places where Dreamception's patterns don't make sense. That's what I did for the center of Fire Cave.

As followers may know from my Interstellar fan poster, ice photos taken with a macro lens can have an uncanny aspect, suggesting something not quite of Earth. So when I heard about DreamCeption for IoS, that sounded like something I should check out.

Sure enough: here's an example of patterns that Dreamception added to one of my ice photos, Fire Cave:

That's at low-resolution. Here's a sample of what Dreamception can do at a higher resolution, from a small portion of the upper right of the image:

That's impressive for the consumer market. The processing load must be substantial, which is why it runs in the cloud on supercomputers.

The app's based on earlier work at Google, originally set up so that its artificial-intelligence program, called DeepDream, could recognize elements of photos, say, distinguishing a dog from a doghouse. Turns out that DeepDream can work the other way, superimposing details onto photos in a search for patterns and meaning. Filters such as "afterlife" impose buildings, faces, and all kinds of crazy things on ice photos:

Using the Dreamception app on an iPad is easy -- just upload an image from your Camera Roll folder, select a filter, hit submit, then save back to the Camera Roll. It's possible to process an image with one filter and then apply another filter to that result.

After some experimenting, I think the most striking results come that way, from using the filters in series. For higher resolution you may have to break your image into pieces and recombine the Dreamception output with a graphics app, such as one of my faves, ProCreate.

ProCreate's layer tool is also a good way to restore some of your original image, in places where Dreamception's patterns don't make sense. That's what I did for the center of Fire Cave.

Published on September 20, 2015 06:34

August 13, 2015

Summer reading: Quick book reviews

The Martian

: Fun read, and reflects an amazing amount of research and thought by the author. The family enjoyed it even more than I did. Many novels have featured marooned individuals, on Mars and elsewhere, but this has a uniquely fast pace as things continue to wrong and then even wronger. I think one reason it's so currently popular is that the plot affirms hopes among the Colonize Mars crowd: if we could just hurl a few plucky humans to the surface, along with a few hundred tons of supplies, they'd take it from there and make us all proud.

The Martian is based on an appealing fantasy, but it's not a good basis for a manned space program. In my conversations with astronauts about human vs. robot roles in space, they convinced me that when it comes to distant places like Mars and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, they'd prefer that robots do the advance work, dig shelters against cosmic rays, and turn up hazards long before the humans touch down. Quite likely, the first astronauts to arrive in the vicinity wouldn't land at all. Rather they'd handle the robots' mission control from orbit. But that's too wonky for fiction.

Lawrence in Arabia : Many good insights about T.E. Lawrence, the scheming British and French, the Turks, residents of Palestine, and the Saudi tribes. We hear much about what drove T.E. to such heights and such depths. But I found the side stories of other intriguers so prominently mentioned on the jacket -- presented in a parallel thriller style -- as weakly tied to the main story, because those people had little to do with Lawrence's exploits. Are they there for contrast, to show how much Lawrence did and how much they didn't do? I couldn't tell, but it was distracting. I did appreciate the occasional revisionist info correcting fictions in the David Lean motion picture.

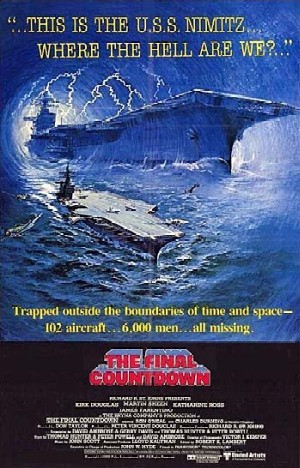

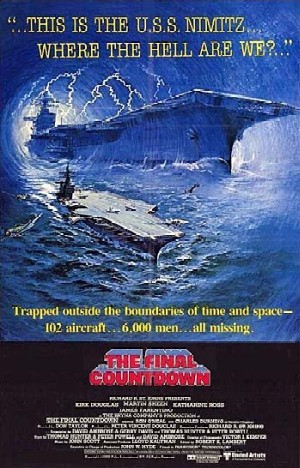

Time and Again: A classic. A wonderful book, worth reading numerous times. Jack Finney is one of the few time-travel writers to realize that great narration and characters are more important than dropping time-travelers into the Turning Points of History. One of many examples of the latter cliche is The Final Countdown , where the writers dispatch a modern aircraft carrier through a "time storm," conveniently to arrive off Hawaii hours before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Here's the poster:

The Theory That Wouldn't Die: Reading this now: nonfiction about the origin of the Bayes Theorem and why it took more than two centuries to catch hold. Why does an old theory about using prior scenarios and posterior corrections matter? It's proven vital to good decision-making in uncertain and fuzzy situations. If the wreck of Malaysia Airlines MH370 is ever found -- no, make that when it's found -- the use of Bayesian methods is likely to share some of the credit ... as it did with the location of the remains of Air France Flight 447.

The Martian is based on an appealing fantasy, but it's not a good basis for a manned space program. In my conversations with astronauts about human vs. robot roles in space, they convinced me that when it comes to distant places like Mars and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, they'd prefer that robots do the advance work, dig shelters against cosmic rays, and turn up hazards long before the humans touch down. Quite likely, the first astronauts to arrive in the vicinity wouldn't land at all. Rather they'd handle the robots' mission control from orbit. But that's too wonky for fiction.

Lawrence in Arabia : Many good insights about T.E. Lawrence, the scheming British and French, the Turks, residents of Palestine, and the Saudi tribes. We hear much about what drove T.E. to such heights and such depths. But I found the side stories of other intriguers so prominently mentioned on the jacket -- presented in a parallel thriller style -- as weakly tied to the main story, because those people had little to do with Lawrence's exploits. Are they there for contrast, to show how much Lawrence did and how much they didn't do? I couldn't tell, but it was distracting. I did appreciate the occasional revisionist info correcting fictions in the David Lean motion picture.

Time and Again: A classic. A wonderful book, worth reading numerous times. Jack Finney is one of the few time-travel writers to realize that great narration and characters are more important than dropping time-travelers into the Turning Points of History. One of many examples of the latter cliche is The Final Countdown , where the writers dispatch a modern aircraft carrier through a "time storm," conveniently to arrive off Hawaii hours before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Here's the poster:

The Theory That Wouldn't Die: Reading this now: nonfiction about the origin of the Bayes Theorem and why it took more than two centuries to catch hold. Why does an old theory about using prior scenarios and posterior corrections matter? It's proven vital to good decision-making in uncertain and fuzzy situations. If the wreck of Malaysia Airlines MH370 is ever found -- no, make that when it's found -- the use of Bayesian methods is likely to share some of the credit ... as it did with the location of the remains of Air France Flight 447.

Published on August 13, 2015 19:36