James R. Chiles's Blog, page 6

October 29, 2016

WikiLeaks, Casting a Wide Net

My name's in WikiLeaks too ... My article on the Hughes 500P "Quiet One" stealth helicopter, built for a 1972 CIA wiretapping mission into North Vietnam, was copied into an email by a Stratfor guy. This was part of chatter about the stealth MH-60 used in the Bin Laden raid.

Here's the WikiLeaks link:

https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/docs/28/2846145_re-military-ct-aw-and-st-modified-h-60s-with-stealth.html

Here's the article as it appeared in Air&Space:

http://www.airspacemag.com/military-a...

Here's one of the photos that Shep Johnson sent me, showing the ship parked at the secret base in Laos:

Here's the WikiLeaks link:

https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/docs/28/2846145_re-military-ct-aw-and-st-modified-h-60s-with-stealth.html

Here's the article as it appeared in Air&Space:

http://www.airspacemag.com/military-a...

Here's one of the photos that Shep Johnson sent me, showing the ship parked at the secret base in Laos:

Published on October 29, 2016 11:16

October 20, 2016

Fellowship of the Ring Finger: Safety tips from an oil-rig medic

I'm not a big follower of celebrity news, but Lindsay Lohan did a service by letting people know about a severe finger injury during a boating expedition. Apparently one of her rings snagged as the anchor line ran out, injuring a digit. It might make help people more careful.

The word for the injury that can happen when a ring snags is avulsion. Think of eating a corn dog on a stick – the corn dog slides off the stick bite by bite. Among other celebrity-ring-finger sufferers are Jimmy Fallon and soccer star Kevin McHugh.

Prevention is a lot better than relying on surgery to make it right. I saw the prevention mindset in action minutes after I landed on a Transocean deepwater drillship far out in the Gulf of Mexico called Discoverer Enterprise for a magazine article. I spent four days watching the drilling and completion of a deepwater well for BP. It was an impressive vessel, with two drilling rigs:

As a first-time visitor, my first job upon leaving the helideck was to grab my gear and sit down with the ship's medic for a safety briefing, which I figured would cover just a few basics like my lifeboat station.

The medic did that, but there was a good deal more. He started by showing me around the clinic, which looked impressive enough, then made this case: “But this isn't for surgery and I'm not an MD. If you get seriously hurt out here it'll take at least four hours for a copter to come and fly you to a hospital, so you've got to watch out for yourself.”

He was not only persuasive, he was persistent. For one thing, he insisted I remove my wedding ring. I pointed out that the only time before that I'd tried to get it off, it wouldn't budge past the first knuckle. (That was before going up the the gantry at Cape Kennedy's Vertical Assembly Building to take a look at the Columbia. The main reason for this was NASA's worry about jewelry or other loose objects falling from visitors onto the delicate tiles. My NASA minder had accepted that removal of my ring was impractical, and had been satisfied with wrapping some tape around my ring finger.

Not good enough, the Discoverer Enterprise medic said. This was a working drill rig with a lot of moving parts, big ones, and a ring was an accident waiting to happen: it could catch on something and tear my finger off, or electrocute me if I closed an open circuit with it.

(Apparently he hadn't given much credit to the plot of Abyss , where a wedding ring is a lifesaver, not a life-taker: in the movie, the character played by Ed Harris saves himself from drowning in his undersea drilling rig by jamming his wedding ring into a bulkhead door before it closes, giving rescuers a chance to force it open.)

So the medic showed me how to get around the knuckle problem by wrapping the joint with waxed flossing string. That compressed it enough to let me work the ring off in good order.

Here's another tip he taught me, which I use daily: He said one of the most avoidable accidents he sees on board oil rigs is to fall down the stairs. It's easy to do, he said, because the stairs on ships are steep and made of metal, and tend to be slippery, given that everybody is wearing boots and the surfaces collect moisture.

“Just keep a hand on damn handrail, and you'll be okay,” he said. I did, and still do.

The word for the injury that can happen when a ring snags is avulsion. Think of eating a corn dog on a stick – the corn dog slides off the stick bite by bite. Among other celebrity-ring-finger sufferers are Jimmy Fallon and soccer star Kevin McHugh.

Prevention is a lot better than relying on surgery to make it right. I saw the prevention mindset in action minutes after I landed on a Transocean deepwater drillship far out in the Gulf of Mexico called Discoverer Enterprise for a magazine article. I spent four days watching the drilling and completion of a deepwater well for BP. It was an impressive vessel, with two drilling rigs:

As a first-time visitor, my first job upon leaving the helideck was to grab my gear and sit down with the ship's medic for a safety briefing, which I figured would cover just a few basics like my lifeboat station.

The medic did that, but there was a good deal more. He started by showing me around the clinic, which looked impressive enough, then made this case: “But this isn't for surgery and I'm not an MD. If you get seriously hurt out here it'll take at least four hours for a copter to come and fly you to a hospital, so you've got to watch out for yourself.”

He was not only persuasive, he was persistent. For one thing, he insisted I remove my wedding ring. I pointed out that the only time before that I'd tried to get it off, it wouldn't budge past the first knuckle. (That was before going up the the gantry at Cape Kennedy's Vertical Assembly Building to take a look at the Columbia. The main reason for this was NASA's worry about jewelry or other loose objects falling from visitors onto the delicate tiles. My NASA minder had accepted that removal of my ring was impractical, and had been satisfied with wrapping some tape around my ring finger.

Not good enough, the Discoverer Enterprise medic said. This was a working drill rig with a lot of moving parts, big ones, and a ring was an accident waiting to happen: it could catch on something and tear my finger off, or electrocute me if I closed an open circuit with it.

(Apparently he hadn't given much credit to the plot of Abyss , where a wedding ring is a lifesaver, not a life-taker: in the movie, the character played by Ed Harris saves himself from drowning in his undersea drilling rig by jamming his wedding ring into a bulkhead door before it closes, giving rescuers a chance to force it open.)

So the medic showed me how to get around the knuckle problem by wrapping the joint with waxed flossing string. That compressed it enough to let me work the ring off in good order.

Here's another tip he taught me, which I use daily: He said one of the most avoidable accidents he sees on board oil rigs is to fall down the stairs. It's easy to do, he said, because the stairs on ships are steep and made of metal, and tend to be slippery, given that everybody is wearing boots and the surfaces collect moisture.

“Just keep a hand on damn handrail, and you'll be okay,” he said. I did, and still do.

Published on October 20, 2016 05:51

September 29, 2016

Hold the High Ground: Helicopter war at the top of the world

Watching this week's fighting across the Line of Control that separates the forces of Pakistan and India in Kashmir reminded me to post another excerpt from my book on the social history of helicopters, The God Machine. The section is about how helicopters participated in one of the more obscure exchanges of fire between the two countries, and it also concerned Kashmir.

Note on this week's headlines: while there have been many high-stress moments between the two nations (such as after the attack on India's Parliament, or the massacre at Mumbai), the latest fighting has real potential to grow beyond anything we've seen in SE Asia so far, because there seems to be a feeling that the presence of nuclear weapons on the opponent's side shouldn't be a deterrent to escalation. It's a flashpoint that popped up when I was researching my article on the history of DEFCON alerts.

==

Starting in 1984, a unique helicopter war took shape across the Karakoram Range. Called the Siachen Conflict, it lasted almost two decades, and was highest-altitude war in history.

The dispute dated to 1949 and a disagreement over the exact course of the India-Pakistan border where it passed through the old kingdom of Kashmir. The disagreement was academic until an Indian Army officer noticed in 1977 that the Pakistanis were issuing permits for mountaineering parties to climb certain high mountains that India claimed. A race was on to control the Siachen Glacier and three high passes. At 50 miles long and two miles wide, the Siachen was one of the world’s largest glaciers outside of the polar regions.

In a secret mission called Operation Cloud Messenger, the Indian Army used helicopters to reach the high ground first, in April 1984. Indian troops planted fiberglass igloos at altitudes as high as 22,000 feet in the Saltoro Range forming the west rim of the glacier.

Most of the fighting was conducted with cannons and mortars, which fired any time that the weather was clear enough to pick out a target. Indian Mi-8 helicopters brought light cannons to 17,000 feet and troops dragged the hardware the rest of the way, a few agonizing feet at a time. While the lower-altitude Pakistanis could depend on trucks and pack animals, Indian forces were totally dependent on helicopters for the last stage of their supply chain, and for lifting out hundreds of men debilitated by the conditions.

The machine of choice was the Aerospatiale Lama, along with an Indian-manufactured version called the Cheetah. For almost 20 years, each side attempted to leapfrog the other, looking for gun emplacements that could shell but not be shelled in return. One solution: the high-altitude helicopter raid.

In April 1989 a Lama helicopter carried a squad of Pakistani troops one at a time and dropped them onto a saddle-shaped ridge at Chumik Pass, altitude 22,100 feet, allowing them to sneak up on an Indian post.

The high-altitude war ended with a cease-fire in 2003.

Note on this week's headlines: while there have been many high-stress moments between the two nations (such as after the attack on India's Parliament, or the massacre at Mumbai), the latest fighting has real potential to grow beyond anything we've seen in SE Asia so far, because there seems to be a feeling that the presence of nuclear weapons on the opponent's side shouldn't be a deterrent to escalation. It's a flashpoint that popped up when I was researching my article on the history of DEFCON alerts.

==

Starting in 1984, a unique helicopter war took shape across the Karakoram Range. Called the Siachen Conflict, it lasted almost two decades, and was highest-altitude war in history.

The dispute dated to 1949 and a disagreement over the exact course of the India-Pakistan border where it passed through the old kingdom of Kashmir. The disagreement was academic until an Indian Army officer noticed in 1977 that the Pakistanis were issuing permits for mountaineering parties to climb certain high mountains that India claimed. A race was on to control the Siachen Glacier and three high passes. At 50 miles long and two miles wide, the Siachen was one of the world’s largest glaciers outside of the polar regions.

In a secret mission called Operation Cloud Messenger, the Indian Army used helicopters to reach the high ground first, in April 1984. Indian troops planted fiberglass igloos at altitudes as high as 22,000 feet in the Saltoro Range forming the west rim of the glacier.

Most of the fighting was conducted with cannons and mortars, which fired any time that the weather was clear enough to pick out a target. Indian Mi-8 helicopters brought light cannons to 17,000 feet and troops dragged the hardware the rest of the way, a few agonizing feet at a time. While the lower-altitude Pakistanis could depend on trucks and pack animals, Indian forces were totally dependent on helicopters for the last stage of their supply chain, and for lifting out hundreds of men debilitated by the conditions.

The machine of choice was the Aerospatiale Lama, along with an Indian-manufactured version called the Cheetah. For almost 20 years, each side attempted to leapfrog the other, looking for gun emplacements that could shell but not be shelled in return. One solution: the high-altitude helicopter raid.

In April 1989 a Lama helicopter carried a squad of Pakistani troops one at a time and dropped them onto a saddle-shaped ridge at Chumik Pass, altitude 22,100 feet, allowing them to sneak up on an Indian post.

The high-altitude war ended with a cease-fire in 2003.

Published on September 29, 2016 19:26

September 22, 2016

Gunfights of the Old West: Not always cinematic

Occasionally trends in movie-making catch my interest. Not many studios make Western movies now, but two are in the theaters, a remake of The Magnificent Seven and something called Stagecoach.

This return to the Western genre prompted me to think about a relative, an ex-guerrilla fighter of the Civil War named James J. Chiles. I knew Chiles died of gunshot wounds during a fight with a deputy marshal in downtown Independence, Missouri, in 1873. I knew the town had quite a reputation for violence at the time. Being just east of the Missouri River Independence was not the Wild West, but Wild Midwest.

And I knew James Chiles had a long and bloody record. He killed at least four people in fights following the Civil War and a lot more during the war, because he rode with the rebel bands led by William Quantrill and “Bloody Bill” Anderson. He joined in the murderous raid on Lawrence, Kansas, which attempted to shoot down every able-bodied man in the Jayhawker stronghold. Chiles must have been comfortable with guns, lots of them: a typical horseman in Quantrill's group carried six revolvers and a carbine.

Here's a picture of Chiles taken during the war:

My great-great aunts were furious when my parents gave me the first name James, but my folks figured enough years had passed to let it go. Or maybe it was acknowledgment that for all his faults, Chiles was bigger than life. He was on a first name basis with Wild Bill Hickok and Frank and Jesse James. Harry Truman thought enough of him to note that James Chiles was his uncle by marriage.

So ... did Chiles's death scene in Independence measure up to what we expect from Western downtown-showdowns? Local papers called him a "noted desperado," after all. First, the odds are against the fight being on an epic scale. There were surprisingly few movie-worthy street battles in all the decades of the real West, and even fewer walk-down duels. Among the authentic battles were the shootout at the OK Corral, the Lincoln County War, and a string of fights about county seats.

These were way outnumbered by fictional face-to-face shootouts, such as those featured in the two Magnificent Seven movies, Clint Eastwood's westerns, High Noon, The Wild Bunch, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Open Range, and heaps of others,

Chiles's death by gun was tragic but hardly epic. The newspaper reports don't agree on everything that happened on Sunday, September 21, 1873, but the events certainly came quickly:

That afternoon Chiles was upset with a town deputy marshal named James Peacock, and he found Peacock and his son on a sidewalk in the town square. (The reason isn't clear but might have gone back to when Chiles was a lawman himself. Chiles was a saloon owner at this time.)

Chiles had his own son, named Elijah, with him. Chiles walked up to Peacock and slapped the deputy. Peacock struck back and as usually happens in real fights, the men lost their balance and fell to the boardwalk, grappling.

It might have ended there except Chiles' son Elijah saw a revolver fall out of Chiles' pocket as the men separated and started to gain their feet. Elijah grabbed the gun and shot the deputy in the back, wounding him but not critically.

Peacock drew his own gun and shot James Chiles in the forehead, killing him instantly. Peacock's son Charles found another gun and shot Elijah Chiles, who died soon after. Another shot winged the city marshal as he arrived.

By Western standards Chiles probably would have been cast as one of the villains in a black hat, one who falls in the last scene, so perhaps he measured up to some of the fictional standard after all.

This return to the Western genre prompted me to think about a relative, an ex-guerrilla fighter of the Civil War named James J. Chiles. I knew Chiles died of gunshot wounds during a fight with a deputy marshal in downtown Independence, Missouri, in 1873. I knew the town had quite a reputation for violence at the time. Being just east of the Missouri River Independence was not the Wild West, but Wild Midwest.

And I knew James Chiles had a long and bloody record. He killed at least four people in fights following the Civil War and a lot more during the war, because he rode with the rebel bands led by William Quantrill and “Bloody Bill” Anderson. He joined in the murderous raid on Lawrence, Kansas, which attempted to shoot down every able-bodied man in the Jayhawker stronghold. Chiles must have been comfortable with guns, lots of them: a typical horseman in Quantrill's group carried six revolvers and a carbine.

Here's a picture of Chiles taken during the war:

My great-great aunts were furious when my parents gave me the first name James, but my folks figured enough years had passed to let it go. Or maybe it was acknowledgment that for all his faults, Chiles was bigger than life. He was on a first name basis with Wild Bill Hickok and Frank and Jesse James. Harry Truman thought enough of him to note that James Chiles was his uncle by marriage.

So ... did Chiles's death scene in Independence measure up to what we expect from Western downtown-showdowns? Local papers called him a "noted desperado," after all. First, the odds are against the fight being on an epic scale. There were surprisingly few movie-worthy street battles in all the decades of the real West, and even fewer walk-down duels. Among the authentic battles were the shootout at the OK Corral, the Lincoln County War, and a string of fights about county seats.

These were way outnumbered by fictional face-to-face shootouts, such as those featured in the two Magnificent Seven movies, Clint Eastwood's westerns, High Noon, The Wild Bunch, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Open Range, and heaps of others,

Chiles's death by gun was tragic but hardly epic. The newspaper reports don't agree on everything that happened on Sunday, September 21, 1873, but the events certainly came quickly:

That afternoon Chiles was upset with a town deputy marshal named James Peacock, and he found Peacock and his son on a sidewalk in the town square. (The reason isn't clear but might have gone back to when Chiles was a lawman himself. Chiles was a saloon owner at this time.)

Chiles had his own son, named Elijah, with him. Chiles walked up to Peacock and slapped the deputy. Peacock struck back and as usually happens in real fights, the men lost their balance and fell to the boardwalk, grappling.

It might have ended there except Chiles' son Elijah saw a revolver fall out of Chiles' pocket as the men separated and started to gain their feet. Elijah grabbed the gun and shot the deputy in the back, wounding him but not critically.

Peacock drew his own gun and shot James Chiles in the forehead, killing him instantly. Peacock's son Charles found another gun and shot Elijah Chiles, who died soon after. Another shot winged the city marshal as he arrived.

By Western standards Chiles probably would have been cast as one of the villains in a black hat, one who falls in the last scene, so perhaps he measured up to some of the fictional standard after all.

Published on September 22, 2016 17:34

May 2, 2016

Powerful Machines Need Finesse

Last week I saw a set of land-clearing machines munch their way across a triangular vacant lot in less than a day. I'd heard about such equipment but had never had a chance to see them close up.

Basically, the first machine (the feller-buncher) cuts down trees; a second machine, the skidder, drags the timber to a staging area; and a third machine, a tracked excavator with a grabber attachment, feeds the maw of a fourth machine, the horizontal grinder. The grinder shoots the chips into a semi-trailer.

Later in the day, two more tracked machines went over the ground to prepare for parking-lot work: a stump-grinder and a mulcher.

The feller-buncher looks similar to a trackhoe, but at the end of its boom it has a hydraulic attachment with a really big circular saw and a gripper. The operator rotates and tilts the attachment to align with a trunk or branch, and pushes in the saw blade. Using the gripper above the saw, he can hold on to the newly-cut section to set it into a pile, or can push it over to land on the other side.

Here's a view of the feller-buncher at work:

A newbie operator would be well-advised to watch a seasoned one at work, before taking the controls. A good operator learns more than how to handle the many levers; he or she needs to learn safety and economy of motion. Feller-bunchers can cost well over a quarter-million dollars and a careless operator can cause a lot of damage to the machine, nearby people, and structures. One challenge is that the feller-buncher is always working around stumps, which can damage the undercarriage or throw it off balance at a bad time.

While the machine is capable of taking down a big tree with a single saw-cut, instead this operator took down big and even medium-sized trees one bite at a time. This avoids overloading the feller-buncher and saves the skidder operator a lot of time in gathering up the felled timber.

See this time-lapse of the feller-buncher, spanning less than an hour of equipment time:

Basically, the first machine (the feller-buncher) cuts down trees; a second machine, the skidder, drags the timber to a staging area; and a third machine, a tracked excavator with a grabber attachment, feeds the maw of a fourth machine, the horizontal grinder. The grinder shoots the chips into a semi-trailer.

Later in the day, two more tracked machines went over the ground to prepare for parking-lot work: a stump-grinder and a mulcher.

The feller-buncher looks similar to a trackhoe, but at the end of its boom it has a hydraulic attachment with a really big circular saw and a gripper. The operator rotates and tilts the attachment to align with a trunk or branch, and pushes in the saw blade. Using the gripper above the saw, he can hold on to the newly-cut section to set it into a pile, or can push it over to land on the other side.

Here's a view of the feller-buncher at work:

A newbie operator would be well-advised to watch a seasoned one at work, before taking the controls. A good operator learns more than how to handle the many levers; he or she needs to learn safety and economy of motion. Feller-bunchers can cost well over a quarter-million dollars and a careless operator can cause a lot of damage to the machine, nearby people, and structures. One challenge is that the feller-buncher is always working around stumps, which can damage the undercarriage or throw it off balance at a bad time.

While the machine is capable of taking down a big tree with a single saw-cut, instead this operator took down big and even medium-sized trees one bite at a time. This avoids overloading the feller-buncher and saves the skidder operator a lot of time in gathering up the felled timber.

See this time-lapse of the feller-buncher, spanning less than an hour of equipment time:

Published on May 02, 2016 20:10

April 26, 2016

Exit Strategy

Operating a tracked skid-steer machine recently, gathering trees into piles, reminded me of a subject that gets too little attention: the exit strategy.

The Cat model I was using is fully glass-enclosed, including heavy mesh guarding the side windows. It has a lot of safety features that make sense, many of which are aimed at preventing the operator from getting crushed.

It's front-entry, with a door that will open only if the lift arms have put the tool on the ground, level and lowered. That's because the loader bucket on the lift arms will block the door from opening more than a few inches if the controls haven't put the tool in a fully level and lowered position.

And many emergencies might kill the engine in use, and keep the lift arms from reaching the rest position: sliding down a slope, or rolling over in a creek, or an engine fire.

How to get out? There's an "egress window" behind the operator's seat, which can be dislodged by tugging on a lanyard. While much smaller than the door, it's big enough for an operator to slip out. In case of a fuel fire, which could put a wall of flame across the rear exit path, I'd be inclined to smash the front window and get out that way.

A concept that stuck with me in the sinking-helicopter escape class was the need to look at escape options immediately on entering a helicopter, an airliner, or a building: meaning, before any sign of emergency. Once things start to go wrong, there probably won't be time.

The Cat model I was using is fully glass-enclosed, including heavy mesh guarding the side windows. It has a lot of safety features that make sense, many of which are aimed at preventing the operator from getting crushed.

It's front-entry, with a door that will open only if the lift arms have put the tool on the ground, level and lowered. That's because the loader bucket on the lift arms will block the door from opening more than a few inches if the controls haven't put the tool in a fully level and lowered position.

And many emergencies might kill the engine in use, and keep the lift arms from reaching the rest position: sliding down a slope, or rolling over in a creek, or an engine fire.

How to get out? There's an "egress window" behind the operator's seat, which can be dislodged by tugging on a lanyard. While much smaller than the door, it's big enough for an operator to slip out. In case of a fuel fire, which could put a wall of flame across the rear exit path, I'd be inclined to smash the front window and get out that way.

A concept that stuck with me in the sinking-helicopter escape class was the need to look at escape options immediately on entering a helicopter, an airliner, or a building: meaning, before any sign of emergency. Once things start to go wrong, there probably won't be time.

Published on April 26, 2016 16:46

February 13, 2016

Call to Adventure: When pax have to land the plane

If you've earned any kind of pilot's license, even the simplest single-engine-land license like me, you've probably thought about what you might do if called on to land a plane on which you're riding. It doesn't happen often (fortunately) but there are cases. Most common is when someone has to take the controls of a light plane after his or her spouse is out of action. But what about an airliner?

In December 2014 United Airlines passenger Mark Gongol heard such a call, because the aircraft commander had suffered a heart attack and was out of action. Gongol went forward and explained to the first officer that he had plenty of experience on Air Force jets. He helped her divert for a landing by operating the radios and acting as a backup.

But what if both pilots are out of action, and there's no jet-rated pilot in coach or first class? Here's an interesting Quora answer, explaining how a steely-nerved passenger could land a late-model B737 in an emergency, with guidance from air traffic control:

While researching aerospace articles over the years, working with instructors in professional-quality training simulators, I've sampled a variety of jet-powered aircraft, and it was humbling!

One adventure was trying to land a simulated 737 at then-National Airport in Washington. I finally made it, but only after much assistance from a seasoned instructor. He handled the throttles so I could concentrate on the yoke, flaps, and rudder pedals, but it was still quite difficult; a critical skill turned out to be using the trim switches on the yoke. A later challenge was lining up a B-2 bomber with the refueling boom behind a KC-10 air tanker. (That simulator facility at Whiteman AFB had the strictest security precautions of any military installation I've visited, BTW.)

My takeaway: there's no substitute for small, well-timed inputs. In the 737, the aircraft and its engines responded slowly to control changes, so it was easy to fall behind ... and fall to the ground.

In December 2014 United Airlines passenger Mark Gongol heard such a call, because the aircraft commander had suffered a heart attack and was out of action. Gongol went forward and explained to the first officer that he had plenty of experience on Air Force jets. He helped her divert for a landing by operating the radios and acting as a backup.

But what if both pilots are out of action, and there's no jet-rated pilot in coach or first class? Here's an interesting Quora answer, explaining how a steely-nerved passenger could land a late-model B737 in an emergency, with guidance from air traffic control:

While researching aerospace articles over the years, working with instructors in professional-quality training simulators, I've sampled a variety of jet-powered aircraft, and it was humbling!

One adventure was trying to land a simulated 737 at then-National Airport in Washington. I finally made it, but only after much assistance from a seasoned instructor. He handled the throttles so I could concentrate on the yoke, flaps, and rudder pedals, but it was still quite difficult; a critical skill turned out to be using the trim switches on the yoke. A later challenge was lining up a B-2 bomber with the refueling boom behind a KC-10 air tanker. (That simulator facility at Whiteman AFB had the strictest security precautions of any military installation I've visited, BTW.)

My takeaway: there's no substitute for small, well-timed inputs. In the 737, the aircraft and its engines responded slowly to control changes, so it was easy to fall behind ... and fall to the ground.

Published on February 13, 2016 07:31

February 12, 2016

How to Park That Crane, Continued

Updating my post on the fatal crane mishap in Lower Manhattan last week ...

The city has confirmed that the model was a Liebherr LR1300. Reporters at one of the city's press conferences asked if that meant the crane weighed 300 tons, or could lift that much; the answer is that in Liebherr's model numbers the "300" refers to the maximum hoist capacity under ideal conditions, meaning a short boom held at a high angle. It doesn't apply to the way the crane was rigged on Broadway and Worth Street, with a boom and a jib long enough to hoist HVAC gear to the top of a tall building. Here's the laydown zone (photo, FDNY):

Newsday did a good piece with interviews of crane experts on factors that investigators from the city's Department of Buildings will be checking ... things like, what operators should do to reduce the risk that a crane will overturn when lowering the boom and jib. And it may be that local wind-tunnel effects also played a role.

The proper procedure when weather-safing a long boom and jib is for the operator to run out the winch and set the hook block on the ground while the boom is still at a high angle.

Doing that eliminates a big weight that would otherwise be hanging at the end of a very long arm as the operator lowers the structure to the street. That's a lot of leverage.

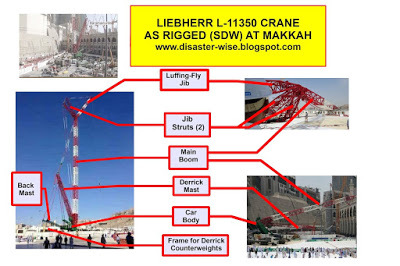

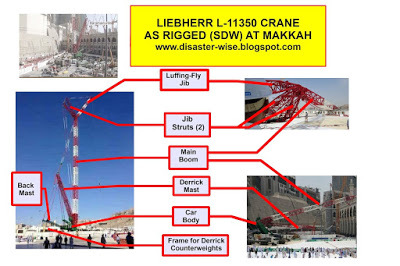

Further, say the experts, the next smart practice is to lower the luffing jib (the smaller lattice structure at the end of the boom) into a vertical position, and only then lower the boom until the tip of the jib touches the street. The terminology makes more sense when looking at the diagram I did after the crane-overturning disaster last September in Saudi Arabia. The Liebherr that fell in KSA was a good deal bigger than the one that fell in New York, and it fell backward rather than forward, but from what I read, it had the same general rigging:

As with lowering the hook block to the street, lowering the jib goes far to reduce the crane's tendency to overturn.

These two steps are particularly important when the crane lacks a trailer-mounted stack of counterweights.

Due to the fatality the city's Department of Investigations will issue a report in months to come.

The city has confirmed that the model was a Liebherr LR1300. Reporters at one of the city's press conferences asked if that meant the crane weighed 300 tons, or could lift that much; the answer is that in Liebherr's model numbers the "300" refers to the maximum hoist capacity under ideal conditions, meaning a short boom held at a high angle. It doesn't apply to the way the crane was rigged on Broadway and Worth Street, with a boom and a jib long enough to hoist HVAC gear to the top of a tall building. Here's the laydown zone (photo, FDNY):

Newsday did a good piece with interviews of crane experts on factors that investigators from the city's Department of Buildings will be checking ... things like, what operators should do to reduce the risk that a crane will overturn when lowering the boom and jib. And it may be that local wind-tunnel effects also played a role.

The proper procedure when weather-safing a long boom and jib is for the operator to run out the winch and set the hook block on the ground while the boom is still at a high angle.

Doing that eliminates a big weight that would otherwise be hanging at the end of a very long arm as the operator lowers the structure to the street. That's a lot of leverage.

Further, say the experts, the next smart practice is to lower the luffing jib (the smaller lattice structure at the end of the boom) into a vertical position, and only then lower the boom until the tip of the jib touches the street. The terminology makes more sense when looking at the diagram I did after the crane-overturning disaster last September in Saudi Arabia. The Liebherr that fell in KSA was a good deal bigger than the one that fell in New York, and it fell backward rather than forward, but from what I read, it had the same general rigging:

As with lowering the hook block to the street, lowering the jib goes far to reduce the crane's tendency to overturn.

These two steps are particularly important when the crane lacks a trailer-mounted stack of counterweights.

Due to the fatality the city's Department of Investigations will issue a report in months to come.

Published on February 12, 2016 16:45

February 6, 2016

Another Large Crane Mishap, NYC

About the fatal crane accident in lower Manhattan yesterday, which happened while the operator was lowering the crane boom and jib to reduce toppling risks from a rising wind ... From the sparse photos, this unit looks like a Liebherr LR1300, which wouldn't be counted as a supercrane. The crane was rigged for a long reach and light pick.

It was carrying a lot of mast and jib, 565 feet of it according to reports, but it must have handled such a dead load before, since crews had put the sections together on the ground, after which the operator raised it to position.

Given that the car body flipped over on its back, I'd guess that the luffing cables didn't snap; that is, the falling mast and jib dragged the car body over on its back, with the rising counterweights providing the momentum.

Some things the NYC investigators will look at: was there extra weight on the hook, mast, or jib that would have overbalanced it; did the pavement collapse under the front of the tracks? I assume that the crane had been sitting on timber mats, but I can't tell from the photos, which show the crane after it overturned. Mats are important to keeping big cranes upright.

Kudos to news reporters that call this a tip-over rather than a collapse. When a structure falls intact, as this crane apparently did, I wouldn't call that a collapse.

Second note to reporters: nearly all the photos posted are of the mast and jib in the lay-down zone. Yes, these tell us the tragic damage such a machine can cause, but it doesn't convey much information compared to a close look at the car body, undercarriage, counterweights, crane mats, and hoist rigging.

Terminology for big crawler cranes like this is available in my post about the crane tip-over near the Grand Mosque at Makkah.

Also, here's a reposting of my item "How to Park Your Super-Crane," fixing a broken photo link.

It was carrying a lot of mast and jib, 565 feet of it according to reports, but it must have handled such a dead load before, since crews had put the sections together on the ground, after which the operator raised it to position.

Given that the car body flipped over on its back, I'd guess that the luffing cables didn't snap; that is, the falling mast and jib dragged the car body over on its back, with the rising counterweights providing the momentum.

Some things the NYC investigators will look at: was there extra weight on the hook, mast, or jib that would have overbalanced it; did the pavement collapse under the front of the tracks? I assume that the crane had been sitting on timber mats, but I can't tell from the photos, which show the crane after it overturned. Mats are important to keeping big cranes upright.

Kudos to news reporters that call this a tip-over rather than a collapse. When a structure falls intact, as this crane apparently did, I wouldn't call that a collapse.

Second note to reporters: nearly all the photos posted are of the mast and jib in the lay-down zone. Yes, these tell us the tragic damage such a machine can cause, but it doesn't convey much information compared to a close look at the car body, undercarriage, counterweights, crane mats, and hoist rigging.

Terminology for big crawler cranes like this is available in my post about the crane tip-over near the Grand Mosque at Makkah.

Also, here's a reposting of my item "How to Park Your Super-Crane," fixing a broken photo link.

Published on February 06, 2016 13:47

January 14, 2016

Institutional Memory and the Silver Tsunami, Part 2

How to forge a long-lasting, collective memory that leads to safer operations? That's the subject of this followup post to Part 1.

Physical markers can be valuable memory aids. Old stone monuments on hillsides in Japan, erected following long-ago tsunami, warn those who look for them (photo, CBS News):

Even better are functional monuments, like this building in Banda Aceh that held up against the 2004 event (photo, Daily Telegraph):

Even temporary markers like lockout tags save lives if in conjunction with physical barriers like locks that prevent a valve wheel from being turned, or a blind being unbolted.

The New London explosion – the worst school catastrophe in US history – illustrates the most costlymethod to build a memory: high-profile, landmark cases that resonates strongly with the public and lawmakers. Soon after, laws were passed requiring odorants in natural gas for sale, and the registration of professional engineers. Also influential were the gas leak at Bhopal, the collapse of the Quebec Bridge in 1907, the Chernobyl reactor explosion, and the Northeast Blackout of 1965.

But even the most vivid memories fade, and the ranks turn over. How to keep them fresh? On July 6, 1988, Steve Rae was an electrical technician aboard the Piper Alpha rig at the time a chain of mistakes led to a natural-gas leak from a high-pressure pipe.

The chain of events promptly killed 167 men. Twenty years later he took the podium in front of 130 students at a petroleum technician's school to relive the day, its aftermath, and its costly lessons like the importance of a safety-case approach to prevention. "I attended three funerals on the same day,” he told the newly minted graduates, “and that will never leave me.”

Assuming that institutional memory is important, we have to consider this tough question: Will it always make the critical difference? Not alone, it won't. The loss of Challengerseared across NASA and its contractors and made another solid-rocket booster failure very unlikely, it didn't prevent the loss of Columbiaseventeen years later.

A common objection to proposals that would fire up a major effort to gather and preserve an institutional memory is that the effort will drain thousands of hours of otherwise productive time, in additional to consultant costs. And once it's done, who'll have the time to go through a mass of recollections that seems less relevant by the year? Won't the competition take advantage of our hard-won knowledge? That's short-sighted, according to Trevor Kletz: “If we tell other people about our accidents, then in return they may tell us about theirs, and we shall be able to prevent them from happening to us.”

I think two broad types of collective memory are achievable and worthwhile in high-risk industries, each in its way. And they don't have to be a time-burner.

The two types are motivational memoryand working memory.

A motivational memory is less about technical details and more about remembering the needto work cooperatively and safely.

Why do newly graduating structural engineers in Canada join in the ritual of the Iron Ring? It's not a refresher on statics and dynamics, it's a reminder that people die in collapses if experts don't sweat the details. Jack Gillum has given speeches about the catastrophic collapse of walkways at Kansas City's Hyatt Regency Hotel in 1981. Gillum, as the engineer of record, was found negligent in not catching a fatal flaw in revised shop drawings. He lost his Missouri license over it and 114 people lost their lives that night. Many more were injured in the collapse. A firefighter had to perform an amputation with a chain saw. I heard Gillum speak at an engineers' forensic convention fourteen years ago, and what he said that day remains with me. Further, I believe that when employees are injured on the job, managers who controlled the job site are obligated to visit them in the hospital, and attend funerals too.

Working memory: rather than taking aside all employees for long recorded interviews as they approach retirement, consider strengthening the day to day, functional memory as held in the minds of high-performance teams. Confronted with the need to design a new line of cars from scratch, Chrysler split the job among one hundred “tech-clubs,” each responsible for a key component or assembly. By forcing early companionship between design engineers, marketers and suppliers, Chrysler found it could speed development and cut costs. One advantage of a team approach is that expertise is broadly distributed, lowering the risk that a single employee's departure could cripple a critical operation. At its best, that's how the American military works, putting hugely consequential decisions in young hands, mentored by old hands.

Another argument for taking a team approach is that a team is, or can be, much more than the sum of its parts. According to psychologists who study memory formation both individual and collective, people remember an incident most vividly if they've participated in a group that discussed it afterward. Safety-oriented tailgate talks at jobsites are a good time to bring up lessons learned, fresh off the docket.

Group discussions about accidents and close calls also build up the motivational memory. Through such discussions, even people who weren't at the scene of an explosion feel the emotional impact, and it inspires them to go the extra kilometer. As Yogi Berra might have said, no one wants to experience disaster déjà vuall over again.

Physical markers can be valuable memory aids. Old stone monuments on hillsides in Japan, erected following long-ago tsunami, warn those who look for them (photo, CBS News):

Even better are functional monuments, like this building in Banda Aceh that held up against the 2004 event (photo, Daily Telegraph):

Even temporary markers like lockout tags save lives if in conjunction with physical barriers like locks that prevent a valve wheel from being turned, or a blind being unbolted.

The New London explosion – the worst school catastrophe in US history – illustrates the most costlymethod to build a memory: high-profile, landmark cases that resonates strongly with the public and lawmakers. Soon after, laws were passed requiring odorants in natural gas for sale, and the registration of professional engineers. Also influential were the gas leak at Bhopal, the collapse of the Quebec Bridge in 1907, the Chernobyl reactor explosion, and the Northeast Blackout of 1965.

But even the most vivid memories fade, and the ranks turn over. How to keep them fresh? On July 6, 1988, Steve Rae was an electrical technician aboard the Piper Alpha rig at the time a chain of mistakes led to a natural-gas leak from a high-pressure pipe.

The chain of events promptly killed 167 men. Twenty years later he took the podium in front of 130 students at a petroleum technician's school to relive the day, its aftermath, and its costly lessons like the importance of a safety-case approach to prevention. "I attended three funerals on the same day,” he told the newly minted graduates, “and that will never leave me.”

Assuming that institutional memory is important, we have to consider this tough question: Will it always make the critical difference? Not alone, it won't. The loss of Challengerseared across NASA and its contractors and made another solid-rocket booster failure very unlikely, it didn't prevent the loss of Columbiaseventeen years later.

A common objection to proposals that would fire up a major effort to gather and preserve an institutional memory is that the effort will drain thousands of hours of otherwise productive time, in additional to consultant costs. And once it's done, who'll have the time to go through a mass of recollections that seems less relevant by the year? Won't the competition take advantage of our hard-won knowledge? That's short-sighted, according to Trevor Kletz: “If we tell other people about our accidents, then in return they may tell us about theirs, and we shall be able to prevent them from happening to us.”

I think two broad types of collective memory are achievable and worthwhile in high-risk industries, each in its way. And they don't have to be a time-burner.

The two types are motivational memoryand working memory.

A motivational memory is less about technical details and more about remembering the needto work cooperatively and safely.

Why do newly graduating structural engineers in Canada join in the ritual of the Iron Ring? It's not a refresher on statics and dynamics, it's a reminder that people die in collapses if experts don't sweat the details. Jack Gillum has given speeches about the catastrophic collapse of walkways at Kansas City's Hyatt Regency Hotel in 1981. Gillum, as the engineer of record, was found negligent in not catching a fatal flaw in revised shop drawings. He lost his Missouri license over it and 114 people lost their lives that night. Many more were injured in the collapse. A firefighter had to perform an amputation with a chain saw. I heard Gillum speak at an engineers' forensic convention fourteen years ago, and what he said that day remains with me. Further, I believe that when employees are injured on the job, managers who controlled the job site are obligated to visit them in the hospital, and attend funerals too.

Working memory: rather than taking aside all employees for long recorded interviews as they approach retirement, consider strengthening the day to day, functional memory as held in the minds of high-performance teams. Confronted with the need to design a new line of cars from scratch, Chrysler split the job among one hundred “tech-clubs,” each responsible for a key component or assembly. By forcing early companionship between design engineers, marketers and suppliers, Chrysler found it could speed development and cut costs. One advantage of a team approach is that expertise is broadly distributed, lowering the risk that a single employee's departure could cripple a critical operation. At its best, that's how the American military works, putting hugely consequential decisions in young hands, mentored by old hands.

Another argument for taking a team approach is that a team is, or can be, much more than the sum of its parts. According to psychologists who study memory formation both individual and collective, people remember an incident most vividly if they've participated in a group that discussed it afterward. Safety-oriented tailgate talks at jobsites are a good time to bring up lessons learned, fresh off the docket.

Group discussions about accidents and close calls also build up the motivational memory. Through such discussions, even people who weren't at the scene of an explosion feel the emotional impact, and it inspires them to go the extra kilometer. As Yogi Berra might have said, no one wants to experience disaster déjà vuall over again.

Published on January 14, 2016 16:58