Russell Roberts's Blog, page 402

June 25, 2020

More Mistaken Motivated Justifications for Minimum Wages

Here’s a letter to the New York Times:

Editor:

Seema Jayachandran reports that “new research shows that raising the minimum wage improves workers’ productivity” – and thus, according to the research, causes no unemployment because the increase in productivity enables employers to afford to pay the higher wages (“How a Raise for Workers Can Be a Win for Everybody,” June 18).

I’m skeptical. If raising wages causes worker productivity to rise by enough to justify the pay hike, each employer would already have raised the wages it pays; there’d be no need for an enforced wage hike in the form of a raised minimum wage.

To her credit, Ms. Jayachandran anticipates this objection by arguing that “What unlocked these gains was government action: All nursing homes in a community had to pay employees more. That eliminated competitive disparities that might have made individual operators reluctant to raise wages unilaterally.”

But this explanation fails. If – as is claimed – raising worker pay increases worker productivity by enough to justify the pay increase, no employer that individually raises workers’ wages would have to raise the prices it charges to customers. The increased worker productivity would cover the higher wage expenses, and the resulting improvement in operating efficiency would push prices lower, not higher.

Sincerely,

Donald J. Boudreaux

Professor of Economics

and

Martha and Nelson Getchell Chair for the Study of Free Market Capitalism at the Mercatus Center

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA 22030

…..

See also David Henderson’s take.

The quality of the economic theorizing that is used to justify minimum wages is appallingly weak.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 38 of the May 9th, 2020, draft of the important forthcoming monograph from Deirdre McCloskey and Alberto Mingardi, The Illiberal and Anti-Entrepreneurial State of Mariana Mazzucato:

Consumers are not passive objects of an entrepreneur’s manipulative schemes, no more than an architect’s clients are passive objects of her vision. The feedback from consumers, of course, shapes the product no less than does the producer’s design. Consider twenty-thousand new food products, most of which fail. (The statist will consider this a fault of innovism: what a waste! For some reason she does not think similar venturing in, say, books or music requires a State to narrow the options.)

DBx: The reality identified here by McCloskey and Mingardi is among the many that advocates of industrial policy either miss or regard as a bug of free markets rather than as a feature. Either way, industrial policy is not really meant to steer the market, for industrial policy intentionally rids the economy of some substantial amount of feedback from consumers – that is, industrial policy rids the economy of a central feature of the market.

A sensible implication to draw from the above quotation from McCloskey and Mingardi is this: If you want a vivid image of what the actual results of industrial policy will be relative to the actual results of markets, compare the actual architecture of Soviet-suppressed eastern Europe to that of liberal countries.

In contrast, if you want an image of what are the hoped-for results of industrial policy from its advocates, simply clean up in your mind the actual buildings in Soviet-suppressed eastern Europe. Put two or three sparkles on those spotless yet still-colorless structures! Further imagine that happy and contented people, all forever smiling, frolic in the common areas while within these fine and uniform housing blocs the residents securely dine, party, relax, sleep, and make love. Grateful for the guidance and wisdom of their national leaders, all residents hope and expect that their lives and surroundings will continue, as they are, indefinitely, generation after generation. Meanwhile, in market-oriented countries – if we continue with our portrait of the imaginings of industrial-policy advocates – nearly everyone lives in ramshackle and dilapidated mud or wooden huts, miserable with shrinking wages and as they gaze upon the gleaming towers that house rapacious billionaires whose riches were ripped from workers and consumers.

June 24, 2020

Bonus Quotation of the Day…

… is an observation offered by George Will in his recent, excellent podcast with Juliette Sellgren; it occurs just after the 35-minute mark:

One of America’s biggest problems is that our intelligentsia is so unintelligent.

Cases are Not Deaths

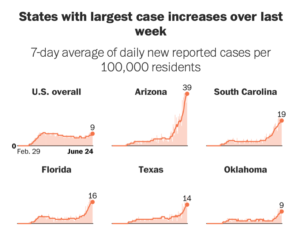

Until very recently the Washington Post, on the first page of its website, tracked, using a bar graph, the daily number of U.S. covid deaths. It has stopped doing so. Now it tracks, on its front page, daily new covid cases.

I have no idea what motivated the WaPo‘s decision to shift from prominently tracking daily covid deaths to tracking, instead, daily new covid cases. But because the former – daily deaths – continues to fall while the latter – daily new cases – is rising, this shift in reporting serves to keep covid fears higher than these would likely be had the WaPo continued to prominently report the daily number of covid deaths.

This biased impression is further worsened by the WaPo‘s practice of reporting, in addition to daily new covid cases nationally, also daily new covid cases of a handful of states – those states that are experiencing especially large increases, relative to other states, in daily covid cases.

Some Links

When anybody defending the accused is automatically accused of the same crime, and any demand for evidence of the charge is seen as an extension of the original crime, you are following the logic of a witch hunt.

Someone has to stop this, and first and foremost that means the liberal establishment. The leaders of universities, foundations, museums, the media and corporations need to draw on their remaining moral authority to make the case for a liberal society. There is a risk that anyone who speaks up, however reasonably, will become a mob target. But if one or two lead, perhaps others will follow.

George Melloan reviews Matthew Klein’s and Michael Pettis’s book, Trade Wars are Class Wars. A slice from the review:

What does ring true is that China is in some trouble. Authoritarian regimes invariably misallocate resources, and, as the book details, the Communist Party has excelled at economic waste. Its state-owned enterprises have run up huge bank debts, many of which yield no interest and won’t be repaid. Indeed, the country is swimming in debt. The authors say that “tightening credit” is needed but add that it could end up “strangling investment before complementary reforms have succeeded in lifting household incomes and boosting domestic consumption.” If wage cuts and unemployment result, China’s political system “might not survive.”

Robert Samuelson laments the sad reality that “the mother of all bailouts isn’t finished yet.”

The old paradigms missed the causes of these problems in ways that highlight the appeal of the “patterns of sustainable specialization and trade” paradigm. Despite its seeming novelty, this paradigm is not a new theory of macroeconomics; rather, it reaches back to the roots of modern economics in the classical economists of the 18th and 19th centuries. Adam Smith and David Ricardo — two of the most prominent economists of the era — explained the benefits of trade based on specialization and comparative advantage, respectively. These concepts remain as useful today as they were when Smith and Ricardo first articulated them.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 241 of the Mercatus Center’s 2016 re-issue of my late colleague Don Lavoie’s more-relevant-than-ever 1985 volume National Economic Planning: What Is Left? (references deleted; link added; original emphasis):

When the central argument of this book, the knowledge problem, was first made some sixty years ago, the radical idea of comprehensive planning as a hopeful alternative to the status quo was at its peak. Today the radical ideology of planning is intellectually bankrupt. All that remains are meek suggestions to try yet one more variation on the century’s dominant theme of noncomprehensive planning. But this policy does not resolve the knowledge problem; it merely substitutes a form of destructive parasitism on the market process in place of its earlier unachievable goal of dispensing with market processes altogether. The knowledge problem shows that the freely competitive market order makes more effective use of the information that lies dispersed throughout society than can any of its participants. This means that noncomprehensive planning is blind interference into a complex order, interference which can succeed in protecting and enhancing monopoly and privilege, but which cannot improve the productive capacity of a modern technologically advanced economy.

DBx: A frequently repeated fallacy today goes something like this: “Yes, yes, Mises and Hayek showed convincingly that full-on socialism – ‘comprehensive’ economic planning by the state – is unworkable. These economists demonstrated the inescapable reality that state officials can’t acquire and process all the knowledge necessary to consciously create an economic organization that performs as well as, and much less outperforms, the free-market order. But we advocates of industrial policy today aren’t proposing full-on socialism; we are proposing more modest interference with the market process. We don’t wish to totally replace markets with socialist planners; we wish only to replace parts of markets with democratically accountable officials who will help to steer the nation’s market to a better destination. We proponents of industrial policy today merely seek to prevent the free market from behaving like the drunk donkey that it is. We proponents of industrial policy today simply with to guide the market as a ship is guided with a compass.”

Sounds reasonable. But it’s not. While piecemeal use of tariffs here, subsidies there, and this prescription and that proscription issued by government bureaucrats invested with discretionary power are unlikely to ruin an economy as completely and as quickly as would full-on socialism, such industrial policy nevertheless cannot overcome the knowledge problem.

Contrary to the belief of today’s advocates of industrial policy, the knowledge problem as identified by Mises and Hayek does not kick in only with full-on socialism. The knowledge problem arises whenever politicians and their hirelings attempt to improve economic outcomes by overriding market processes. And this reality holds for politicians and their hirelings who are democratically accountable no less than it does for politicians and their hirelings who are as secure in their power as was a 15th-century Hapsburg.

The fact that, say, a protective tariff on some good deemed by government officials to be “economically strategic” will not alone crash an entire economy as would full-on socialism does not imply that that tariff imposes no net harm on the economy. The imposer of the tariff cannot know what he claims to know – namely, that the economic benefits to the country from the tariff will outweigh its costs. The imposer of the tariff cannot possibly understand the complexity of the economic forces at work that cause the market price of the tariffed good to be what it is; he cannot possibly know what will be all the reactions of buyers and sellers, at home and abroad, to the price made artificially high. The imposer of the tariff – regardless of his academic credentials or his experience and success in private industry – can see only the surface of the economic phenomena into which he coercively imposes his visible hand. Yet beneath this surface lies vast, massive, incomprehensible complexity.

Just as shooting BBs from a BB-gun at a healthy person would not kill that person as would firing at that person several live rounds from an AK-47, industrial policy as proposed by people such as Marco Rubio, Elizabeth Warren, and Oren Cass would not utterly destroy an economy as would inflicting on that economy full-on socialism of the sort that was all the rage a century ago. But peppering a person with BBs still harms that person, and the heavier the peppering, the more harm the person suffers, even if he or she is never killed by the peppering. For the shooter of the BB gun to defend his actions by pointing out that he’s not executing his victim with an AK-47 hardly justifies the shooter’s interference with the person.

…..

I’ve noted many times, and will continue to note, that advocates of industrial policy offer no explanation of how government officials would get the knowledge that they would need in order to direct the economy toward ‘outcomes’ that are better than those that arise in free markets – markets unimpeded with tariffs and subsidies. Advocates of industrial policy content themselves to repeat the banal fact that markets aren’t perfect, and then to gallop, rather like drunk donkeys, to the conclusion that therefore politicians and their hirelings who have the power to coercively override the market’s resource-allocation patterns will outperform markets. Just how politicians and their hirelings will achieve this happy outcome we are never, ever told.

June 23, 2020

Bonus Quotation of the Day…

… is from this new essay – “The dangerous war on supply chains” – by Martin Wolf at the Financial Times:

The obvious way to achieve robustness is to diversify suppliers across multiple locations. Producing in one’s own country is not a guarantee of robustness. Any given location might be affected by a pandemic, hurricane, earthquake, flood, strikes, civil unrest or even war. To put every egg in one basket, even the domestic one, is risky.

Just Wondering

In my latest column for AIER I wander through some of my wonderings. A slice:

I wonder a great deal about people’s misunderstanding of trade. For example, I wonder…

… why, on certain occasions, support for protectionist policies in the United States can be easily drummed up by asserting that some foreign government is intent on artificially restricting Americans’ ability to import goods and services, such as medical supplies. Why do Americans turn for a ‘solution’ to this problem to their own government – a government that has done, and continues to do, far more than has any foreign government to artificially restrict Americans’ ability to import goods and services?

… why, on other occasions, support for protectionist policies in the U.S. can be easily drummed up by asserting that some foreign government is intent on artificially enhancing Americans’ ability to import goods and services, such as commercial aircraft. Why is there no understanding that this complaint is inconsistent with the complaint just above? And more generally, why does anyone believe that we Americans are harmed by foreigners arranging for us to have access to a greater abundance of goods and services?

… why so many Americans believe that they will be made poorer if people in poor countries, through trade, become richer. Why do so many of my fellow Americans believe that the increased ability of foreigners to produce and offer to sell to us high-quality goods and services threatens our prosperity? Do these same Americans believe that their prosperity is threatened if greater numbers of other Americans, say, get better education that enables them – these other Americans – to produce and offer to sell to their fellow Americans high-quality goods and services? Why should we believe that we are benefitted through trade by the enrichment of human beings across town, but that we are harmed through trade by the enrichment of human beings across the ocean?

… why so many Americans fail to understand that international trade cannot make Americans more dependent upon foreigners without making foreigners more dependent upon Americans. Why don’t more people realize that foreigners engage in commerce with Americans in order to get goods and services in exchange from Americans? Asked differently, why do so many people presume that foreigners are stubbornly intent on giving to Americans gifts?

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 39 of the May 9th, 2020, draft of the important forthcoming monograph from Deirdre McCloskey and Alberto Mingardi, The Illiberal and Anti-Entrepreneurial State of Mariana Mazzucato (footnote deleted; link added):

The Enrichment emerged in Britain first, and government spending there was until well into the 20th century focused on the defense of the realm, the protection of the sea routes to India, and the servicing the debt contracted to defeat at last the French. As the economic historian Joel Mokyr puts it, “any policy objective aimed deliberately at promoting long-run economic growth would be hard to document in Britain before and during the Industrial Revolution…. In Britain the public sector by and large eschewed any entrepreneurial activity.”

DBx: Pictured above is the British engineer George Stephenson (1781-1848). Born poor to illiterate parents, and himself illiterate until early adulthood, Stephenson’s creativity and diligence contributed much to the development of railroads.

June 22, 2020

Pittsburgh Tribune-Review: “The Prosperity Pool”

In my column for the January 13th, 2010, edition of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review I wrote about what I call modernity’s “prosperity pool” – vast prosperity consisting of the accumulation of countless tiny drops of economic improvement. (Coincidentally, Art Carden last week, in a column he wrote for AIER, linked to a 2016 piece that I’d written on the prosperity pool.)

You can read my column beneath the fold.

Russell Roberts's Blog

- Russell Roberts's profile

- 39 followers