Russell Roberts's Blog, page 355

November 9, 2020

Agreeing and Disagreeing With Tyler Cowen on Covid-19

What Tyler misses is that those of us who point out that Covid is overwhelmingly a threat only to the old and infirm are thereby identifying an important reason for rejecting the belief that Covid is cataclysmic.

To contend that Covid isn’t cataclysmic is not to contend, or even to imply, that Covid’s dangers aren’t real. They are real, but almost exclusively for old and ailing people. And because of this fact, Tyler is wrong to argue that failure to respond as radically and as indiscriminately as most governments have done would have dangerously discredited governments in the eyes of their citizens. Surely the most credible – surely the “optimal” – response by government is one that is proportionate to the danger posed. And such proportionality requires taking into account relevant realities such as large age-group differences in mortality rates.

But by failing to take account of Covid’s differential impact on people according to their age, governments have compromised their credibility. By falsely treating everyone from kindergartners through college students and even middle-aged folks in normal health as if they all are as imperiled by Covid as are residents of nursing homes, governments signal a disregard for relevant facts. They reveal that they’ll seize upon any crisis, inflate it opportunistically, and use it as an excuse to grab more power regardless of the underlying realities.

In short, contrary to building up its citizens’ trust in the ability and willingness of government to respond effectively to crises, each government that ignored or discounted the importance of the reality that Covid is overwhelmingly a danger to the elderly has given its citizens very good reason to distrust it to respond effectively to future crises.

Some Links

Efforts to guarantee outcomes are at odds with what it means to live in a free society where equality under the law is the guiding principle. So either Ms. Harris was blowing smoke or she wants to change America into a place where liberty takes a back seat to central planning. The latter is called socialism, a system that is not particularly kind to the poor.

Nick Gillespie reflects intelligently on the outcomes of last-week’s U.S. elections.

Also reflecting intelligently is Ethan Yang, he here on communism.

I’m eager to read Virginia Postrel’s new book, The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World. It’ll be released tomorrow.

Pierre Lemieux favors the liberal solution.

Amelia Janaskie reports on Taiwan’s experience with Covid-19. Here’s her conclusion:

According to the lockdown narrative, Taiwan did almost everything “wrong” but generated what might in fact be the best results in terms of public health of any country in the world.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 283 of Kristian Niemietz’s important 2019 book, Socialism: The Failed Idea That Never Dies:

Why do we so easily dismiss the massive gains that capitalism delivers and obsess over its shortcomings? Why are we so desperate for an alternative that we are prepared to give the most horrendous systems a free pass (at least for a while), provided they are not capitalist? Why are (or were) so many well-meaning observers willing to turn a blind eye to Gulags and Laogai, but incandescent with rage when large companies earn a profit, or when some people earn a lot more money than others?

DBx: Why indeed?

These questions are especially appropriate ones to ask on this 31st anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

November 8, 2020

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 295 of Matt Ridley’s excellent 2020 book, How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom:

Thus for innovation to flourish it is vital to have an economy that encourages or at least allows outsiders, challengers and disruptors to get a foothold. This means openness to competition, which historically is a surprisingly rare feature of most societies.

DBx: Distressingly, even the most open and liberal societies are never free of harmful forces aiming to plan, bridle, and direct competition and innovation. Most such forces today in the United States fit under the innocent-sounding name “industrial policy.” Everyone who endorses such a policy as a means of improving the performance of the economy as a whole, or as a means of raising the living standards at least of middle- and lower-income people, presumes that which is impossible: successful soothsaying.

Economic growth of the sort that routinely raises the living standards of middle- and lower-income people requires genuine innovation. Genuine innovation, by its nature, is impossible to predict in any detail. We can predict that in an open, bourgeois, liberal society innovation will regularly occur. Yet no one can predict what the innovations will be, who will produce them, or how their effects will or ‘should’ ripple through the economy over space and time.

Industrial-policy advocates – left, center, and right – simply refuse to acknowledge this reality. They continue to write as if government officials, by imposing tariffs here and dispensing subsidies there, will cause the economy to perform better than one that is open to competition and in which innovation is permissionless. For industrial-policy schemes to work, therefore, government officials must know in detail just how their meddling will affect innovation, and how the innovations they spur will affect the economy at large. In addition, they would have to know what innovations their meddling prevents and how the economy at large will be affected by the prevention of these innovations.

Because no one can know such things, every industrial-policy proponent presumes either that he or she has supernatural powers or that government officials charged with implementing industrial policy will, by some miracle, be invested with such powers.

It is not too much to say that every industrial-policy scheme is inherently whackadoodle, in the same way that belief in palm-reading or in the predictive powers of fortune cookies is whackadoodle.

November 7, 2020

If You Look at the Welfare Only of Protected Producers…

Here’s a letter to the Wall Street Journal:

Editor:

American Iron and Steel Institute CEO Kevin Dempsey argues that Pres. Trump’s steel tariffs “worked” (Letters, Nov. 6). For evidence he points to U.S. steel producers’ increased capacity utilization and the protection of steel-worker jobs.

By so arguing Mr. Dempsey completely evades the chief economic objection to protectionism – namely, the resulting reduced access of consumers to other goods and services and the destruction of other firms and jobs elsewhere in the domestic economy. Obliging consumers to spend more on steel necessarily leaves them with less to spend on other things, while arranging for steel producers to increase output necessarily drains domestic resources away from other productive uses.

Mr. Dempsey’s argument is akin to that of the leader of a burglary ring who, having successfully bribed the police to turn a blind eye to his outfit’s predations, insists that his bribery “worked” because it results in more intense use of crow bars and lock picks, as well as more jobs for burglars.

Looking at the welfare only of protected producers makes no more sense than looking at the welfare only of protected thieves.

Sincerely,

Donald J. Boudreaux

Professor of Economics

and

Martha and Nelson Getchell Chair for the Study of Free Market Capitalism at the Mercatus Center

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA 22030

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 33 of Deirdre McCloskey’s and Art Carden’s new (2020) book, Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich: How the Bourgeois Deal Enriched the World (original emphasis; footnote deleted; link added):

Giving people what they want, and are in justice willing to pay for when they can, is a good system. “Economics,” writes Jeffrey Tucker, “is not just about making money. It’s also about a chance to be valuable to others, to yourself.” By contrast, giving people what the critics of “capitalism” think they should want, or that people do want but want to get magically free of sacrifice of their own efforts for other people, burdening another person for their own gain, is a hideously selfish society.

DBx: Yes. A trillion-and-two times yes.

All schemes of protectionism enable some people to leech off of their fellow citizens. Protectionism, in order to artificially enrich the few, denies to the many the right to spend their incomes as they choose. By artificially narrowing buyers’ options, protectionism relieves the protected of the obligation to make themselves as useful as possible to others.

This reality is true for run-of-the-(steel)-mill protectionism as well as for more ‘comprehensive’ versions hawked as “industrial policy.”

Hawkers of economic protectionism differ from each other on the surface. Most don’t bother to mask their economic ignorance. Their thinking is never more than the “imports are bad because ‘we’ don’t make them” tic. This gaggle of protectionists is surprisingly large; it includes Donald Trump, Joe Biden, and Bernie Sanders.

A smaller group of protectionists – fancying themselves to have a better understanding of economics than they actually do – gild their arguments for protectionism with some economic jargon here, a few out-of-context quotations from Adam Smith there, and trains of twisted or incomplete ‘reasoning’ throughout. This group of protectionists boasts among its membership Oren Cass, Julius Krein, and Robert Reich.

But, substantively, the final result of the intellectual efforts of this smaller group is the same as that which is emitted by the many protectionists whose economic ignorance is blatant. Both groups of protectionists value only the benefits bestowed on the protected. The blatantly ignorant simply don’t see the greater damage done by protectionism, while the more ‘sophisticated’ group – having heard something about this damage but never really understanding it – write nonsensically about how this damage is unreal, justified, or can be miraculously avoided.

In the end, all protectionists peddle policies that make human beings less useful to each other. All protectionists advocate policies that enable the relative few to prey on the many.

November 6, 2020

Some Links

For me, the most important part of elections is that the transfer of power should be peaceful. The Democrats were wrong to scream “Russia!” and to attempt to remove President Trump via impeachment, and I think less of them for doing so. If Biden is declared the winner and then the Republicans scream “Fraud!” for months on end, I will think less of them.

I know all the comebacks to this. The stakes are too great! We know that Biden won by fraud (as if you personally have evidence for that claim that would convince a neutral observer)! We can’t let them get away with it! Those arguments do not sway me. If we replace the electoral process with a litigation war and street demonstrations, the resulting banana republic will be worse than anything that the Democrats implement in office.

Eric Boehm corrects Donald Trump’s ironic interpretation of the counting of mail-in votes.

Alberto Mingardi explains that he and Deirdre McCloskey wrote The Myth of the Entrepreneurial state in order to help stem the rising tide of enthusiasm for industrial policy. This enthusiasm, be aware, is rising not only on the political left through people such as Marianna Mazzucato, but also on the political right (for example, Oren Cass) and even in the political middle (for example, Brink Lindsey). I predict, by the way, that Mazzucato, Cass, and other industrial-policy enthusiasts will largely ignore Deirdre’s and Alberto’s wonderful book – the reason being that these enthusiasts have no good retort to the book’s arguments other than to continue to insist that, somehow, government officials will, in addition to shedding their political inclinations, come to possess supernatural powers to foretell and engineer the future.

Juliette Sellgren talks with GMU Econ alum Eli Dourado about technology and stagnation.

John Tamny rightly calls out Victor Davis Hanson for the latter’s ignorance of economics.

Pick almost any starting point over the last half-century. Extreme poverty has been crushed and may be on its way to disappearing in the next decade or two. In 1990, roughly 1.9 billion people lived in extreme poverty (defined as making less than $1.90 per day). Since then, world population has grown from 5.28 billion to 7.8 billion, while the number of people living in extreme poverty has dropped to 650 million and continues to fall.

That’s because the world has been getting richer—the whole world, not just the top 1 percent. From 1900 to 2016, global GDP per capita grew by about 621 percent. Even global inequality—the gap between rich and poor countries—has started to decline appreciably over the last two decades.

Hey, you enthusiasts for mandating the wearing of masks, note this.

My intrepid Mercatus Center colleague Veronique de Rugy remembers the late Alberto Alesina. A slice:

I first learned of Alesina from his work on fiscal austerity. In a paper written just before the 2007–2009 crisis, he and Goldman Sachs economist Silvia Ardagna (then at Harvard) showed that fiscal adjustment packages based on expenditure cuts by government are more effective at reducing the public-debt-to-GDP ratio than are packages based on tax increases. Their paper also shows that expenditure cuts are not just conducive to long-term growth, but, under the right circumstances, generate growth in the short term. Finally, if cuts in spending triggered some initial contraction of the economy, it would be mild and short-lived. Do not hope for such mild negative effects with adjustment packages based on tax increases.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from pages 104-105 of the late Hans Rosling’s 2018 book, Factfulness:

The media can’t waste time on stories that won’t pass our attention filters.

Here are a couple of headlines that won’t get past a newspaper editor, because they are unlikely to get past our own filters: “MALARIA CONTINUES TO GRADUALLY DECLINE.” “METEOROLOGISTS CORRECTLY PREDICTED YESTERDAY THAT THERE WOULD BE MILD WEATHER IN LONDON TODAY.” Here are some topics that easily get through our filters: earthquakes, wars, refugees, disease, fire, floods, shark attacks, terror attacks. These unusual events are more newsworthy than everyday ones. And the unusual stories we are constantly shown by the media paint pictures in our heads. If we are not extremely careful, we come to believe that the unusual is usual: that this is what the world looks like.

For the first time in world history, data exists for almost every aspect of global development. And yet, because of our dramatic instincts and the way the media must tap into them to grab our attention, we continue to have an overdramatic worldview. Of all our dramatic instincts, it seems to be the fear instinct that most strongly influences what information gets selected by news producers and presented us consumers.

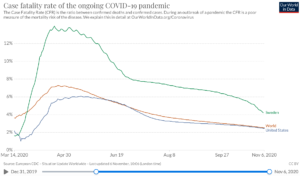

DBx:  Keep in mind the above insight as you encounter the daily breathless reports of rising Covid-19 case counts. At the very least, ask what’s happening with the Covid-19 case fatality rate. However imperfect this particular statistic might be, surely it’s good news that it’s falling. Yet how often do you encounter reports of this good news in newspaper headlines or in top-of-the-hour network radio news announcements?

Keep in mind the above insight as you encounter the daily breathless reports of rising Covid-19 case counts. At the very least, ask what’s happening with the Covid-19 case fatality rate. However imperfect this particular statistic might be, surely it’s good news that it’s falling. Yet how often do you encounter reports of this good news in newspaper headlines or in top-of-the-hour network radio news announcements?

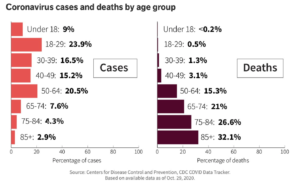

While you have on your big-boy or big-girl thinking cap, inquire also about the age distribution of Covid cases and deaths. And then, perhaps, wonder, for example, why teams in the National Football League get all panicky about some of their players testing positive for Covid, remembering – as you wonder – that these players are all extraordinarily fit and muscular young men who, for a living, on a weekly basis ram themselves mightily into each other.

While you have on your big-boy or big-girl thinking cap, inquire also about the age distribution of Covid cases and deaths. And then, perhaps, wonder, for example, why teams in the National Football League get all panicky about some of their players testing positive for Covid, remembering – as you wonder – that these players are all extraordinarily fit and muscular young men who, for a living, on a weekly basis ram themselves mightily into each other.

If you’re like me and like my friend Lyle Albaugh (from whom I steal the following observation), it seems stunningly silly to freak out about NFL players testing positive for Covid given the enormous risks to their health that is routinely posed by their very profession. (Yes, yes, I know: Covid is contagious while concussions and spinal injuries are not. But unless NFL players work on their off days in hospitals or nursing homes, it’s difficult to see that the cost of preventing these young men from working at their jobs is remotely justified by the resulting benefit.)

November 5, 2020

Talking Economics and Trade with Nate Wadsworth

I very much enjoyed being interview recently by Nate Wadsworth on “The Essential Craftsman.” The topic is basic economics and trade.

Some Links

Covid is not a very dangerous disease for most people. The death rate is probably around 0.2 per cent of those infected, and most who die are elderly and suffering from other medical conditions. The mortality of those in hospital with Covid has almost halved for the over 80s since the start of the epidemic as treatment has improved.

Lockdowns are lethal. They cause more deaths from cancer, heart disease and suicide as well as job losses, bankruptcies, social disintegration and mental illness especially among the young, who are at least risk from the virus. In April sunshine, many people and firms could cope for a short period – once. Today, in November rain, the pain will be far worse. I will be all right, living in a rural area and able to work online, but what of those who started restaurants or live alone in small flats?

There is overwhelming support in the scientific community for national lockdown, say scientists, but the scientific community and the civil service are on secure public-sector salaries and think in top-down ways.

Peter Earle reminds us of Boston’s 2013 lockdown.

Once again, Election Day in America has come and gone with some lingering questions as to when the results will be certified. In the run-up to the presidential contest, each side overflowed with hope about the many wonders its guy, once in power, might bring about. Unfortunately, for those of us who prefer smaller government—for those of us who value individual liberty as an end in itself—neither candidate really promised fiscal solvency or less government interference in our lives.

Despite corporate tax reform, deregulatory efforts, some criminal justice reforms, and an anti-socialist rhetoric, President Donald Trump has shown little interest in free market policies. His administration promised and failed to get rid of the Affordable Care Act and would have likely replaced it with what is best described as Obamacare Light. With the Republicans’ support, Trump opened wide the spending spigot for the Pentagon and its defense contractors. Ditto for other kinds of spending, much of which was irresponsibly funded with debt.

…. and Ilya Somin does the same.

Here are Arnold Kling’s reasonable reflections on Tuesday’s election results.

Russell Roberts's Blog

- Russell Roberts's profile

- 39 followers