Russell Roberts's Blog, page 350

November 24, 2020

Some Links

Traveling back to New York, Newsom’s authoritarian twin in Albany has decreed limits on private gatherings that effectively ban large parties. Translated for those who need it, Andrew Cuomo has joined Newsom with a ban on what makes Thanksgiving great. The problem for Cuomo is that his subjects have stopped listening.

Even better, the law in New York has begun tuning out New York’s power-mad governor. Indeed, as the New York Times reported last week, an upstate sheriff informed the newspaper that “his office” would “never interfere with ‘the great tradition of Thanksgiving dinner.’” It seems this sheriff won’t be the only one to mock what vandalizes ridiculous. Another sheriff in the southern part of the Empire State informed the Times that he would not be “peeking in your window” in an effort to count heads. A third sheriff informed Times reporter Michael Gold that entering houses “to see how many Turkey or Tofu eaters are present isn’t a priority.”

But manifestly it isn’t working. Police are making clear they can’t and won’t enforce such a ban. At a gym outside Buffalo on Friday, dozens of business owners who had met to discuss how to survive new Covid-19 restrictions chased away a health inspector and two sheriff’s deputies who had gone inside to break up the meeting because it violated the governor’s limit. It’s a good example of how relying on government edicts rather than persuasion breeds contempt for both health experts and the law.

David Henderson shares Judith Hermis’s letter to Gavin Newsom.

Art Carden unveils the idiocy that infects Joe Biden’s proposal for a “national supply commander.” A slice:

Biden says we are in trouble because we have relied too heavily on the private sector. However, the problems he wants a National Supply Commander to solve are there because the government wouldn’t leave the private sector alone. As many economists have written, prices are like signal flares. They tell people who want resources most urgently, and they do it with a specificity that goes beyond vague generalizations like “Hospitals need more masks.”

Nick Gillespie talks with Virginia Postrel about her new book, The Fabric of Civilization.

But there is a problem with these mandates: To achieve their ends, they both need blacks to be victims. Whites need blacks they can save to prove their innocence of racism. Blacks must put themselves forward as victims the better to make their case for entitlements.

This is a corruption because it makes black suffering into a moral power to be wielded, rather than a condition to be overcome. This is the power that blacks discovered in the ’60s. It gained us a War on Poverty, affirmative action, school busing, public housing and so on. But it also seduced us into turning our identity into a virtual cult of victimization—as if our persecution was our eternal flame, the deepest truth of who we are, a tragic fate we trade on. After all, in an indifferent world, it may feel better to be the victim of a great historical injustice than a person left out of history when that injustice recedes.

Yet there is an elephant in the room. It is simply that we blacks aren’t much victimized any more. Today we are free to build a life that won’t be stunted by racial persecution. Today we are far more likely to encounter racial preferences than racial discrimination. Moreover, we live in a society that generally shows us goodwill—a society that has isolated racism as its most unforgivable sin.

This lack of victimization amounts to an “absence of malice” that profoundly threatens the victim-focused black identity. Who are we without the malice of racism? Can we be black without being victims? The great diminishment (not eradication) of racism since the ’60s means that our victim-focused identity has become an anachronism. Well suited for the past, it strains for relevance in the present.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 441 of my late Nobel-laureate colleague Jim Buchanan’s June 20th, 2010, lecture in Richmond, VA, “Chicago School Thinking: Old and New,” as the draft of this talk is published, for the first time, in The Soul of Classical Political Economy: James M. Buchanan from the Archives (2020) (edited by Peter J. Boettke and Alain Marciano); in part of this talk Buchanan recalls his graduate-student days at the University of Chicago in the late 1940s:

But we were not, at Chicago, affected by the Harvard-MIT syndrome that led us to proceed as if we were called to be advisers to politicians. Jacob Viner, who left Chicago one term after I arrived, had famously said that the task of economists was to expose fallacies in the arguments of politicians rather than to offer positive advice.

DBx: Viner (pictured here) was correct. He remains correct. And because politicians are an endless source of fallacies, sound economists’ have a full-time job by sticking to this task.

…..

The sound economist understands much better than do most non-economists – and even better than many persons trained in economics – just how unfathomably complex is the modern economy.

The economy looks relatively simple to the untrained eye. We have statistics on artifactual aggregates such as GDP, industrial output, unemployment rates, industrial-concentration ratios, Gini coefficients, annual spending on health care, U.S. merchandise exports and imports, and on and on and on. These statistics give the impression of being records of a reality far more concrete and objective than it really is. (Who decided, for example, what outputs count as “industrial” and which do not? Who decided how to define an industry? Who decided what is and is not to be classified as “merchandise”?)

Statistics such as these – however useful they are (and they often are very useful) – combine with the market’s astonishingly smooth operation to create the false impression that economic reality is much simpler than it really is. The literally trillions of daily adjustments made around the world in light of local knowledge of details are not seen. Yet these adjustments are necessary if the economy is to continue to produce and make widely available items as ‘simple’ as pairs of socks, electrification, and loaves of bread.

Those who propose industrial policy are either ignorant of, or they recklessly ignore the reality of, the need for these trillions of daily, decentralized adjustments to be made – adjustments that are possible only if individuals with local knowledge are both free to make these adjustments, and have incentives to make them in a manner that is productive for the larger economy.

One of the most profoundly important lessons of economics is this ironic one: Only by giving individuals such freedom to make decentralized economic decisions as each deems best, within a system of private property rights and competitively set prices, will the economy perform well for society as a whole. Attempts to consciously, centrally arrange for the economy to perform well for society as a whole – attempts that necessarily suppress the freedom of individuals to make local decisions – result in the economy performing poorly for society as a whole.

Also ignorant of the the unfathomable complexity of the modern economy are those who are not much troubled by Covid-19 lockdowns and other suppressions of economic activity. The economy is not an engine that can be stopped or slowed, and then, at will, started or revved up again. The government doesn’t “run” the economy. And liquidity from central banks, or fiscal “stimulus” from treasury departments, is not really “fuel” for the economy. People in power and with influence who think in this way, by failing to grasp the (I have no better term) unfathomable complexity of the modern economy, pose a far greater danger to the public than is posed by any physical pathogen such as the coronavirus.

November 23, 2020

Tyler vs. Tyler?

In his excellent and thought-provoking 2018 book, Stubborn Attachments, Tyler Cowen writes (on page 93; original emphases):

More practically, the additional wealth that accumulates as a result of economizing on life-saving expenditures does lead people to buy safer cars, to take less risky jobs, and so on. So it can be argued that we will save some number of other lives by invest less in life preservation for the elderly. We don’t know whether an increment of wealth saved will in fact reduce or preserve other human lives, but there is some chance that this might be the case. And this possibility lowers the value of spending a lot of money to extend a human life. So, in a contemporary setting, a human life should probably be valued at less than $4 million, or whatever other sum the willingness-to-pay method, or some other utilitarian calculation is going to serve up.

We may not know the exact correct valuation of an individual life, but we do know that the possibility of commensurability, the pull of the more distant future, the ongoing replenishment of human civilization, and the value of investing in future lives, when considered as a whole exert some downward pressure on how much we should invest in extending the lives of the elderly today. My arguments therefore suggest a lower estimate of the value of a life, including an older life, than most other plausible frameworks, because replacement and replenishment of civilizational flow are considered as one factor among many. Replacement and replenishment should not be taken as the final word, but yes, they do exert downward pressure on our value of life estimates.

To put it more concretely, today in the United States we are spending too much on the elderly and not enough on the young.

DBx: I wonder how Tyler would reconcile this point with his rejection of the relevance of the fact that Covid-19 is overwhelmingly a disease that is fatal to old people – especially very old and infirm people. I don’t doubt that some attempted reconciliation is possible, but I do doubt that I would find such an attempt to be persuasive. (Not that Tyler, or anyone else, should care whether or not I would find it persuasive.)

The lockdowns and other restrictions on economic and social activities are astronomically costly – in a direct economic sense, in an emotional and spiritual sense, and in a ‘what-the-hell-do-these-arbitrary-diktats-portend-for-our-freedom?’ sense. Yet this immense cost is being borne chiefly to extend for a few months or, at most, for a few years the lives of the elderly. That the vast bulk of these costs aren’t paid in the form of cash is irrelevant.

But even looking only at cash payments – and only those made by the U.S. government – we get a monetary-cost figure that surely the Tyler Cowen of 2018 would find excessive. To wit –

Let’s say that the net number of deaths avoided, over the course of the response to Covid, by government lockdowns and other restrictions will, in the end, top out at 1,000,000 – which, in my opinion, is wildly excessive (but we’ll go with it here). And let’s take Tyler’s example of an excessive monetary value-of-individual life of $4 million. The result is that the Covid lockdowns saved $4 trillion worth of human life.

As of September 30th, the U.S. government alone had spent, in response to Covid-19, $1.62 trillion. I cannot find a reliable figure that’s more up-to-date. But taking into account all that the U.S. government has spent additionally since September 30th because of Covid – and also into account what it will spend in the future – and adding to this sum the total amount of money spent by state and local governments in response to Covid, surely we’re getting close to – and perhaps much in excess of – $4 trillion.

Worth it? Not in my book. And, I think, not in the literal book of Tyler Cowen circa 2018. And these expenditures in response to Covid are not the major cost. The major cost is the lost production, the disrupted lives, and the reduced rate – perhaps permanently – of economic growth. Given that one of Tyler’s most intriguing arguments in Stubborn Attachments is that we discount the value of the future far too greatly – implying that we value the present far too much relative to the future – I believe that the 2018 Tyler Cowen would be a most intriguing, perhaps even confrontational, guest of the 2020 Tyler Cowen on Conversations with Tyler. It’s a conversation that I’d very much like to hear!

Wishing that Hans Rosling Were Still Alive

Among the instincts that Rosling warns against is the fear instinct. Noting that “‘frightening’ and ‘dangerous’ are two different things,” Rosling writes that the fear instinct “makes us give our attention to the unlikely dangers that we are most afraid of, and neglect what is actually most risky.” Yes. And Rosling repeatedly advises his readers to understand that the news media naturally appeal to our fear instinct by exaggerating dangers, typically by failing to put them into proper context:

Here are a couple of headlines that won’t get past a newspaper editor, because they are unlikely to get past our own filters: “MALARIA CONTINUES TO GRADUALLY DECLINE.” “METEOROLOGISTS CORRECTLY PREDICTED YESTERDAY THAT THERE WOULD BE MILD WEATHER IN LONDON TODAY.” Here are some topics that easily get through our filters: earthquakes, wars, refugees, disease, fire, floods, shark attacks, terror attacks. These unusual events are more newsworthy than everyday ones. And the unusual stories we are constantly shown by the media paint pictures in our heads. If we are not extremely careful, we come to believe that the unusual is usual: that this is what the world looks like.

For the first time in world history, data exists for almost every aspect of global development. And yet, because of our dramatic instincts and the way the media must tap into them to grab our attention, we continue to have an overdramatic worldview. Of all our dramatic instincts, it seems to be the fear instinct that most strongly influences what information gets selected by news producers and presented to us consumers.

Encountering most of today’s reports and commentary on Covid gives no sense that the median age of Covid victims in the U.S. is the late 70s or early 80s. Or that 79 percent of American Covid victims are 65 years or older. Or that 92 percent of these deaths are of people 55 and older. (The preceding figures are estimated from here.) Or that fully 41 percent of all Covid deaths in the U.S. are of residents of nursing homes. Or that, according to the CDC, the Covid infection fatality ratio for all Americans ages 50-69 is 0.005, while that for Americans ages 70 and older is 0.054.

Were the media to report these figures, Americans’ fear instinct would not be stimulated.

Some Links

Dartmouth economist Douglas Irwin writes in the Wall Street Journal that truths that economists have long known about trade were not proven false or upended by Donald Trump’s peddling of protectionist fallacies. Here’s his conclusion:

All this points to a disappointing—but entirely predictable—set of outcomes that, unfortunately, have damaged the U.S. economy and alienated allies. The president sought to reduce the trade deficit, increase manufacturing employment, change China’s policies, and reach better deals, but fell short on all counts.

“Equal citizenship is not negotiable any more,” Mr. Connerly says. “You get the same rights, same responsibilities. You own just as much cultural stock in the country as anyone else.” Black people “have not always been accorded equal citizenship, I can tell you, because I know a little bit about that,” having been born in the South in 1939. But America has overcorrected for past wrongs. “Black people have been accorded a certain stature in American life” because of their history, Mr. Connerly says. “In the race sweepstakes right now, being black means that you get preferred stock.” Unless you’re a “race advocate,” he adds, “that is not a good thing.”

And here’s Mark Perry on David Horowitz on systemic racism.

George Leef decries the infestation of ‘wokeness’ in collegiate departments of music.

As if we need even more reason to distrust medical information dispensed by government officials.

Jeffrey Tucker revisits asymmetric spread. A slice:

Gradually, and sometimes almost imperceptibly, the rationale for the lockdowns changed. Curve flattening became an end in itself, apart from hospital capacity. Perhaps this was because the hospital crowding issue was extremely localized in two New York boroughs while hospitals around the country emptied out for patients who didn’t show up: 350 hospitals furloughed workers.

That failure was embarrassing enough, given the overwhelming costs. Schools closed, commercial rights were vanquished, shelter-in-place orders from wartime were imposed, travel nearly stopped, all large events were cancelled, and so on. Clearly there needed to be a good, solid, science-based reason for why the politicians and their advisers had, on their own, decided to take away much of what we once regarded as human rights.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from pages 71-72 of Russ Roberts’s splendid 2014 book, How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life:

Everyone can explain why the stock market rose or fell yesterday. No one can predict what it will do tomorrow.

DBx: Who dares deny the truth this observation? Answer: Proponents of industrial policy.

Proponents of industrial policy pose as prophets possessing special knowledge of what particular, detailed economic processes and outcomes will be best for hundreds of millions of their fellow citizens indefinitely into the future. These soothsayers also behave as though they possess knowledge of all the relevant effects – current and future, near and distant, first-order, second order, third order, nth order – of the implementation of their schemes. Industrial-policy proponents must presume themselves to possess such knowledge, for how else can they be sure that their schemes will not uncork ill unintended consequences?

November 22, 2020

Some Links

New York City has enough troubles, with a fiscal crisis, rising crime and a population that can’t wait to leave. It would be nice if it weren’t also plagued by egomaniacal leaders posing as saints of rationality.

Hear! Hear! for California Congressman Tom McClintock! This short speech of his is spot-on. (HT Dan Klein)

Joakim Book writes movingly about the inhumanity of Covid restrictions. Here’s his conclusion:

In a free society, trading, perusing wares, socializing and enjoying the company of others are mutually beneficial, innocent and harmonious actions. In a government-mandated Covid society, these wants are now antagonistic.

Barry Brownstein is rightly thankful for our mutual dependence.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 110 of Deirdre McCloskey’s and Art Carden’s splendid new (2020) book, Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich: How the Bourgeois Deal Enriched the World:

The people studying to become better nudgers, meddlers, bureaucrats, administrators, or Keynesian magicians do damage to the rest of us.

November 21, 2020

Some Covid Links

In reality Covid deaths going from 249,999 to 250,000 is a largely meaningless milestone and the hoariest kind of fake news. When deaths hit 200,000, listeners could already figure out how many more would make 250,000. Many also knew, unmentioned in NPR’s sermon which likened the daily death toll to several jumbo jet crashes, that most of these deaths are from Covid plus other conditions that afflict the old and chronically ill. Still, the 250,000 milestone was the most reported factoid everywhere on Thursday and Friday, so another hint for journalists: If you find yourself straining for ways to sensationalize a claim that listeners have already heard 50 times, maybe just drop it and move on.

In our interesting times, sadly, what is most noticeable is the shrill, hoarse wind of banality that blows from our multibillion-dollar media industry. A contrast last week was a concise insight from a hospital executive buried in a long New Yorker article: “The only way you can eradicate the virus with today’s tools is if you’re a totalitarian government or on an island.”

Also decrying the “blizzard of bogus journalism on Covid” is Jeffrey Tucker. A slice:

There are hundreds of ways to look at Covid-19 data. The Times picked the one metric – the least valuable one for actually discerning whether and to what extent people are sick – in order to generate the result that they wanted, namely that open states look as bad as possible. The result is a chart that massively misrepresents any existing reality. It makes the worst states look great and the best ones look terrible. The visual alone is constructed to make it looks as if open states are bleeding uncontrollably.

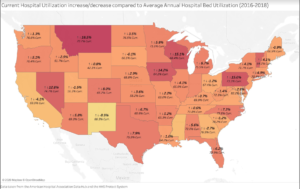

David Stockman (behind a paywall) factually and powerfully pushes back against the media-fueled Covid Derangement Syndrome. A visual slice:

(Apologies for my being unable to make this image larger. It shows current [November 1-9] hospital utilization rates compared to average annual hospital utilization 2016-2018. Today’s reality appears to be nowhere near the “crisis” about which the media and many politicians are screaming.)

And a verbal slice:

Here are the the seven-day averages for the three peak periods. As between the April peak and the seven-day average as of November 18, the number of tests is up by 9.6X, the number of cases stands at 5.1X and WITH-Covid hospitalizations have risen by just 1.2X.

New Tests Per Day (seven-day average):

April 11: 163,400;

July 23: 884,675;

November 18: 1,565,872;

Nov. vs. April: 9.6XNew Cases Per Day (seven day average):

April 11: 39,750;

July 23: 66.500;

November 18: 157,220;

Nov. vs. April: 5.1XWITH-Covid Hospitalizations (seven day average):

April 11: 59,900;

July 23: 59,700;

November 18: 72,000;

Nov. vs. April: 1.3XOf course, the ultimate test of disease severity is the mortality rate, but that metric, fortunately has tracked neither the testing rate nor the daily case count. In fact, the seven day average for November 18 is actually 43% below the peak rate of April.

WITH-Covid Deaths (seven day average):

April 21: 2,116;

August 4: 1,107;

November 18: 1,209;

Nov. vs. April: 0.57X

Amelia Janaskie explains the harm that Covid-19 lockdowns inflict on women.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 158 of Robert Higgs’s August 28th, 2013, blog post, “Creative Destruction – The Best Game in Town” as this post is reprinted in Bob’s excellent 2015 volume, Taking a Stand:

For the losers [today, from economic competition], the perceived remedy of their plight has often been not to make the necessary personal adjustments as well as possible, but to use force, especially state force, to burden or prohibit the more successful competitors in the market. Thus, the market’s critics demand bailouts, subsidies, tax breaks, and corporate and personal welfare of various sorts to soften the blows of the Schumpeterian “perennial gale of creative destruction.” Notice, however, that all such attempts to soften the blows also serve to mute or falsify the messages the market system is sending about where resources can be employed most productively in the prevailing circumstances. Amelioration of the suffering softens the blows, to be sure, but it also slows the process by which wealth is being created and introduces wasteful measures that may, especially if they are state-mandated, become entrenched in the politico-economic system and thereby serve as channels for resource waste and as permanent fetters on real progress.

Russell Roberts's Blog

- Russell Roberts's profile

- 39 followers