Russell Roberts's Blog, page 106

August 25, 2022

Recollecting My First Day of Law School

A recent agreeable Facebook post (pasted below) by GMU law professor Michelle Boardman reminded me of my first day of law school at the University of Virginia. It was late August 1989. All first-year law students were assigned to a “small group,” each group having in it about 32 students. Members of each small group took all first-year required courses together. And for each small group there was appointed a second- or third-year law student to serve as that group’s first-year sherpa.

When my small group first assembled, our sherpa had a bright idea for how to break the ice and have all of the group members get to know each other better. Our sherpa asked each group member to reveal “One thing about you that your mother doesn’t know.”

I distinctly recall being very surprised to discover how many of my fellow first-year law students had traveled through Europe that summer spending what apparently were embarrassingly large sums of their parents’ money the precise dollar amounts of which their mothers had yet to learn. With undergraduate diplomas freshly fisted from schools such as Duke, Stanford, and Yale, my new classmates had jaunted off to explore London, to party in Paris, to backpack along the Rhine, or to frolic in sunny Sicily. All well-earned R&R before the rigors of law school – and all on mom’s & dad’s dimes.

For me, the son of a shipyard worker, finding himself suddenly the peer of several people with open-ended access to their parents’ bank accounts to fund European vacations was startling.

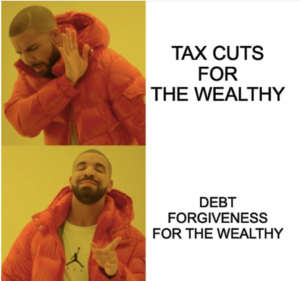

But, hey – thanks to Biden – so very many people now find themselves with access to the bank accounts not only of their parents, but of everyone in the entire country!

…..

Here’s Michelle Boardman’s Facebook post:

When I started college, I was surprised to meet people who, while obviously wealthier than my family, complained about their loans and student aid. They talked about trips to France, cruises, expensive restaurants, and their pricey clothes. My parents paid for two college educations using one military salary, backed by family camping trips, meals at home, and no frills. I wouldn’t have qualified for any help, not because of the salary, but because of their savings. In grad school, I took on loans of my own.

Setting aside for the moment whether the executive branch has the power to force the rest of us to repay others’ loans, I am having the same feeling today. The educational cost system is broken, largely because of government intervention, but this unfair move is at most a few-year “fix.”

The (Il)logic of Retaliatory Industrial Policy

A long-time and very astute correspondent, Felix Finch, was inspired by my recent post on the folly of retaliatory industrial policy to send to me the following e-mail (that I share with his kind permission):

This new penicillin sure is great, but the other hospitals are still using sulfa powder. We must switch back to stay competitive!

Our new Boeing 707 jets cross the Atlantic faster than ever before, but our competitors still use Douglas DC-7 prop planes. We must switch back ourselves!

These Arabic numerals sure make calculations easier, but the bank across the street is still using Roman numerals. We must switch back!

DBx: Yep.

Although industrial policy – the empowering of politicians and bureaucrats, and the ‘experts’ who are consulted, to coercively override the peaceful commercials choices of millions of individuals spending and investing their own money – is widely regarded as “progressive” and ‘scientific,’ the reality is that industrial-policy proponents are no more enlightened than are believers in voodoo and faith healing. Industrial policy is regressive.

Some Links

There is no point in our mincing words. This is a lie. A contrivance. A game. Nobody believes this. It’s an excuse. If it makes it to the Supreme Court, it will lose, and it will deserve to lose. It is facially farcical. Of course “The HEROES Act, first enacted in the wake of the September 11 attacks” does not convey this authority, as the memo claims. At no point, until today, had a single person in America ever believed such a thing. They shouldn’t now.

Jim Geraghty wonders what the old folks in Scranton would think of Biden’s shifting the burden of student loans from the individuals who chose to take out such loans to the taxpayers. Here’s his conclusion:

Why is Biden going ahead with this? Because the demographics most likely to complain about student loans include a lot of progressive Democrats, and Biden needs them to be fired up about the midterms. Biden’s willing to exacerbate inflation and endanger the country’s economy, just in hopes of generating a slight improvement in Democratic turnout in a few months. The old folks of Scranton would be appalled.

Meanwhile, my rough new estimate is that the cost to taxpayers will be $427 billion. To put that in perspective, it is more than the gross domestic product of Hong Kong and 182 countries. For those who support federal social programs, it is nearly 36‐times greater than the federal government spent on Head Start in 2022. And if you support defense spending, it is nearly two‐and‐a‐half times larger than the U.S. Army’s 2022 budget. And this, by the way, does not include non‐cancellation elements of the Biden announcement, including proposals to significantly cut many borrowers’ monthly payments and more generous loan forgiveness in the future.

Well, he did it. Waving his baronial wand, President Biden on Wednesday canceled student debt for some 40 million borrowers on no authority but his own. This is easily the worst domestic decision of his Presidency and makes chumps of Congress and every American who repaid loans or didn’t go to college.

The President who never says no to the left did their bidding again with this act of executive law-making, er, breaking.

…..

Worse than the cost is the moral hazard and awful precedent this sets. Those who will pay for this write-off are the tens of millions of Americans who didn’t go to college, or repaid their debt, or skimped and saved to pay for college, or chose lower-cost schools to avoid a debt trap. This is a college graduate bailout paid for by plumbers and FedEx drivers.

Colleges will also capitalize by raising tuition to capture the write-off windfall. A White House fact sheet hilariously says that colleges will “have an obligation to keep prices reasonable and ensure borrowers get value for their investments, not debt they cannot afford.” Only a fool could believe colleges will do this.

According to Biden, forcing all Americans to help pay the debts of college borrowers is an unfortunate necessity; people who borrowed from the government to go to school are just that badly off. They are ruined, they are desperate, and they need generous U.S. taxpayers to bail them out.

“An entire generation is now saddled with unsustainable debt in exchange for an attempt, at least, at a college degree,” said Biden. “The burden is so heavy that even if you graduate, you may not have access to the middle-class life that the college degree once provided.”

This is quite an indictment of the federal student loan program, so one might have expected that Biden’s generous debt forgiveness plan would be accompanied by serious reforms to the underlying system that produced such inequities. After all, the government is conceding that its loan program has scammed millions of desperate people. Their situation is so dire, their prospects of repayment so dim, that Biden is requiring everyone else to pitch in and help them.

But no, Biden’s debt forgiveness plan will do nothing—absolutely nothing—to fundamentally change the incentive system that created the doom spiral in the first place. Degree-seekers will continue to borrow large amounts of money to buy useless educations; indeed, they might feel even more encouraged to do so now that this precedent has been set.

Also weighing in on Biden’s disgusting ‘forgiveness’ of student-loan debt is Emma Camp.

Steve Davies is pessimistic about at least the next few decades.

Finn McRedmond reports on the likely exaggeration of the numbers on long covid.

In response to David French’s attempt, in a tweet, to deflect blame from Fauci, Jay Bhattacharya tweets:

This tweet misconstrues the nature of Fauci’s power. He held the power to cast legitimate scientific opposition to the ‘fringe’. When he pushed lockdowns and school closures while donning the mantle of The Science(tm), it took an extraordinary politician to oppose him.

Even before I had my own kids, I felt driven to put children first. It’s why I balked at a pandemic strategy that put young people’s needs and desires on the back burner. “I can’t think of another event in history where we offered up our youngest members as sacrificial lambs for the potential to protect our oldest ones,” novelist and essayist Ann Bauer (no relation to me) recently told me. “I’m still gobsmacked that we let it happen.” (As an aside, Bauer’s essay on the hubris underlying “the science,” published by Tablet magazine, is essential reading for any lockdown critic.)

While the Haredim were making noise in their New York and Jerusalem enclaves, a protestant preacher named Artur Pawlowski was protesting lockdowns, masks, and church restrictions in Western Canada. On Easter weekend 2021, reports that Pawlowski was not adhering to the public health orders brought the police to his church. Months later, he was arrested and sentenced.

In addition to a $23,000 fine and 18 months of probation, the judge who sentenced Pawlowski gave him a script about “expert opinion” to read before discussing Covid with his congregants. “Forcing people to say what they do not wish to say—and do not believe—violates all the fundamental freedoms of the Charter,” Father Raymond de Souza, an Ontario Catholic priest and university professor, wrote in an article for the National Post. “It’s what tyrants do.”

As a religious leader, de Souza has an obvious stake in the question: Does the state have the right to interfere in freedom of religious expression? And if so, to what extent? His verdict, delivered in another National Post article: The Canadian government crossed the line. Under the guise of containing a pandemic, politicians and their advisors displayed a “naked urge to extend the reach of the state.”

As Exhibit A, he presented the six-month ban on in-person worship in British Columbia, orchestrated by provincial health officer Bonnie Henry. “Her edict permitted people to meet for an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in the church basement, but that same number of people could not meet in the much larger church to pray,” he noted. “It wasn’t about regulating meetings, but banning worship”—a power play masquerading as public health.

Quotation of the Day…

All these things I’ve stressed – the complexity of the phenomena in general, the unknown character of the data, and so on – really much more point out limits to our possible knowledge than [they are] contributions that make specific predictions possible.

DBx: Would that such an appreciation of society’s enormous complexity – and the resulting intellectual humility that such an appreciation instills – be today more widespread.

August 24, 2022

Yep

HT Adam Martin.

Today we had yet another demonstration of the bizarre principle that, while it’s considered to be appalling to buy votes using your own money, it’s considered to be downright angelic to buy votes using other-people’s money. But I – a college professor – shouldn’t complain. This move by Biden will only further artificially increase demand for higher education (so comically called) and, thus, eventually raise my real income. Still, I do complain, for I detest thievery, bribery, injustice, and populist politics.

Bonus Quotation of the Day…

… is this comment by “JFA” on a recent Marginal Revolution post by Tyler Cowen:

I think it’s humorous that economists who favor the minimum wage usually believe that the market for low wage workers is a monopsony, while also saying things like “the minimum wage will drive low-paying firms out of the market”.

Let’s Not Participate In a TRUE Race to the Bottom

Here’s a letter to someone who disagrees with opposition that I expressed, (in a letter) in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, to industrial policy.

Mr. M__:

Thanks for your e-mail in response to my letter in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal in which I express opposition to industrial policy.

You write:

We can afford to stick to the free market only if other countries do too, but not when places like China are heavy into practicing industrial policy…. We can’t afford not to retaliate in kind.

With respect, I disagree.

The economics of the matter are plain. If industrial policy is an effective means of improving the performance of an economy, our government should use it to improve the U.S. economy regardless of the policies pursued by other governments. But if industrial policy is an effective means of worsening the performance of an economy, our government should avoid using it regardless of the policies pursued by other governments.

Politicians and bureaucrats either are or aren’t able to outperform the free market at spurring economically beneficial innovation and allocating resources efficiently. Such an ability is not miraculously turned on and off by the policies pursued by other governments.

When foreign governments abuse their countries’ economies with industrial policy we Americans should pity the harmed citizens of those foreign lands. We should not, however, respond by abusing our own economy with industrial policy and thereby turn Americans into similar objects of pity.

Sincerely,

Donald J. Boudreaux

Professor of Economics

and

Martha and Nelson Getchell Chair for the Study of Free Market Capitalism at the Mercatus Center

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA 22030

Some Links

David Waugh and Ryan Yonk bid adieu to top U.S. covidocrat Anthony Fauci. A slice:

Dr. Fauci’s career has been one of maximizing budgets and influence for his agencies and himself, all the while handling multiple public health crises with less than stellar outcomes. Economist Gordon Tullock in his book The Politics of Bureaucracy observed that the primary characteristic of a successful bureaucrat is “a desire to rise” and only secondarily does intelligence or competence impact the success of a bureaucrat. This understanding of success within bureaucratic systems is further illustrated by Friedrich Hayek in Chapter 10 of Road to Serfdom, “Why the Worst Get on Top.” While Hayek’s work focuses on tyrannical politicians, the logic clearly applies to government bureaucrats. Indeed Dr. Fauci’s career demonstrates both these realities simultaneously. Far from the neutral expert concerned only with the best outcomes, Dr. Fauci’s career is one of ambition and even “failing upwards.”

Dr. Fauci first rose to public attention in the 1980s during the AIDS crisis. In a 1983 Journal of the American Medical Association article, he speculated that AIDS could be spread through household contact. This resulted in widespread coverage from media outlets, who, citing Fauci’s work, stoked widespread alarm about AIDS transmission while raising his profile significantly. Two months later, Dr. Fauci avoided culpability for promoting the egregious claim by entirely reversing his stance, stating in an interview with the Baltimore Sun, “It is absolutely preposterous to suggest that AIDS can be contracted through normal social contact like being in the same room with someone or sitting on a bus with them. The poor gays have received a very raw deal on this.”

Unfortunately, the social harm from his irresponsible speculation was already done, and his reversed stance only advantaged his own career. His actions during the AIDS epidemic read like a masterclass in ambition and self-preservation.

Anthony Fauci is ending his long and celebrated government career by being widely lauded for getting so much so very wrong on Covid-19.

Now 81 years old, Dr. Fauci has spent 38 years as head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. He has been rightly honored for his many contributions over the decades, most notably during the fight against AIDS, for which he was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom by George W. Bush. But to Covid-19 he brought a monomaniacal focus on vanquishing a single virus, whatever the cost—neglecting the damage that can follow when public health loses sight of the public’s health.

As the lead medical authority to two administrations on Covid-19, Dr. Fauci was unwavering in his advocacy for draconian policies. What were the impact of those policies on millions of Americans? And what would the country look like now had our public health experts taken a different approach? As Dr. Fauci is preparing to leave his post, those are a few of the questions worth asking as we consider his various Covid-19 legacies.

…..

One of the most inexplicable decisions by Dr. Fauci and his team was to ignore natural immunity—that is, the immune response generated by contracting Covid-19. As the evidence mounted that having had the virus was as good as—perhaps even better than—a vaccine, Dr. Fauci and his circle ignored it.

When Dr. Sanjay Gupta asked Dr. Fauci in the Fall of 2021 on CNN: “As we talk about vaccine mandates, I get calls all the time, people say I already had Covid, I’m protected, and now the study says even more protected than the vaccine alone. How do you make the case to them?” Dr. Fauci answered: “I don’t have a really firm answer for you on that.”

Hundreds of studies have now shown that natural immunity is better than vaccinated immunity and that the level of protection vaccines have against severe disease is at the same level of natural immunity alone.

But Dr. Fauci didn’t talk about it.

…..

Just ask the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration — the open letter published in October 2020 that called for focused protection of the most vulnerable instead of blanket shutdowns of schools and businesses. It was authored by Dr. Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford, Dr. Sunetra Gupta of Oxford, and Dr. Martin Kulldorff, then of Harvard, and it was signed by tens of thousands of doctors and scientists.

Drs. Fauci and Collins never talked to these prominent authors to discuss their differing points of view. Instead, they criticized them.

Also from Marty Makary is this counsel of caution about the new vaccine against omicron. A slice:

But where’s the data to support such a sweeping recommendation? The new mRNA vaccines expected to be authorized next month have no clinical trial results that are public. In fact, we know nothing about them. Urging the American people to blindly obey to take a novel mRNA vaccine is not only bad medicine, it’s bad policy. And it’s certainly not following the science.

We just saw this data ambush approach two months ago with the Covid vaccines for babies and toddlers. Here’s how the timeline played out. The White House and public health officials promised them and pushed them hard for children between the ages of 6-months and 5 years. Then vaccine manufacturers released data and declared them safe and effective (the media blindly parroted the message). Here’s the catch. The underlying data actually showed the study sample was too small to make safety conclusions, and most of the claimed effectiveness was statistically invalid. The Pfizer vaccine in babies and toddlers had no statistically significant efficacy. Moderna’s vaccine had an efficacy of just 4% in preventing asymptomatic children aged 6 months to 2 years. (Some European countries have restricted the use of Moderna’s vaccine for anyone under the age of 30 due to the risk of myocarditis). One frustrated CDC official told me the vaccines are so ineffective in young children it wouldn’t matter if you, “inject them with it or squirt it in their face.” Maybe that’s why after a month of pushing Covid vaccination for children under five, only 3% of them got the jab.

Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson decries the lockdown-caused cancer crisis in Britain. A slice:

We’ve had enough, haven’t we? God knows, we are a tolerant people, but we’ve had enough. Because we did as we were told last time and stayed at home to support the NHS, the Office for National Statistics says there are now at least 1,000 more deaths than usual every week. In the spring of 2020, I predicted that lockdown would end up killing more people than Covid – one of only a handful of journalists prepared to ask what was going to happen to all the other ill people if the NHS shut them out. “Pearson wants people to die,” was the standard retort.

Well, today, it’s the lockdown enthusiasts who stand accused of abetting a massacre. Remember when, every night, the news used to update the total of Covid deaths? I’d like to see the BBC and ITV start reporting the daily toll of lives lost because cancers (and heart disease) were found too late. A terrifyingly large and growing number in the corner of the screen might just wake the public up to what I believe is fast becoming one of the biggest avoidable tragedies of modern times.

Ramesh Thakur reports that “Australia’s lockdown and vaccine narrative has fallen apart.” A slice:

Australian authorities in effect copied New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern’s doctrine of the health ministry as the “single source of truth” on coronavirus. The unavoidable consequence of this was attempts, with legacy and social media help, to marginalize and silence all dissenting voices. The more the latter’s warnings come true, the greater is the loss of trust in experts, institutions and ministers.

J.D. Tuccille writes about the dangers of cancel culture. A slice:

“Social pressure to have the ‘right’ opinion is pervasive in America today,” notes Populace, a social-research organization, in a report published this summer. “In recent years, polls have consistently found that most Americans, across all demographics, feel they cannot share their honest opinions in public for fear of offending others or incurring retribution.”

“One important, but underappreciated, consequence of a culture of censorship is that it can lead individuals not only to self-silence, but also publicly misrepresent their own private views (what scholars call preference falsification),” the authors add.

Given the events of recent years, it’s no surprise that some big disconnects are over COVID-19 responses and the management of public schools, which have become merciless battlefields.

“A majority of people say publicly that mask wearing was effective, but they don’t believe it in private,” Populace notes. “Whereas 59 percent of Americans publicly agree that wearing a mask was an effective way to stop the spread of COVID-19, only 47 percent privately hold that view (a 12-point gap).”

Jane Shaw reveals the Hayekian “secret behind our legacy of magnificent music.” A slice:

In 1772, Joseph Haydn and his musicians were spending a long summer performing at the country retreat of Hungary’s Prince Esterhazy. The musicians were restless and wanted to go home, but Esterhazy expected them to stay there as long as he did.

To change the prince’s mind, Haydn wrote a symphony. In the finale, each player, one by one, ends his music, snuffs out his candle, and exits—until only two violinists are left (one being Haydn) to quietly end the piece. Now known as the Farewell Symphony, it persuaded Esterhazy to release the troupe.

Esterhazy’s effort to control the musicians was about as heavy-handed as European governments got with respect to music in those glorious days between, say, 1700 and 1820. (Think, from Vivaldi and Telemann to Mozart and Beethoven.)

Over that period musical performances were enriched and diversified on multiple dimensions. The piano replaced the harpsichord, the cello replaced the bass viola da gamba, Bach brought the organ’s sounds to new heights—to mention just a few changes. Ways to share music—orchestras, quartets, sonatas, concertos, oratorios, and operas—proliferated. The styles we know of as Baroque, Classical, and Romantic began to solidify, and the stunning masterpieces that we love today emerged.

It was not planned, it was not forced, it was not “orchestrated.” It was, as Friedrich Hayek said about the world-wide economy, a spontaneous order.

When we think of the word “spontaneous” these days, we think of something that happens suddenly, like spontaneous combustion from an unlit haystack or the spontaneous outcry of an angry crowd. But the original meaning of the word (and the way Hayek used it) emphasizes the lack of a conscious plan or direction. It stems from a Latin word meaning “of one’s free will.” A complex spontaneous order—such as a modern economy—was not created or designed by anyone but came about by the purposive actions of many.

Unlike most other nations on the planet, the U.S. has substantially reduced its carbon emissions over the past 15 years. This is largely owing to the fracking revolution that replaced a lot of America’s coal with natural gas, which is cheaper and cleaner. Even without the new law, the U.S. was on track to cut emissions substantially by 2030, according to research by the Rhodium Group. Averaging their high and low emission predictions, the U.S. would drop emissions by almost 30% absent the new law. With the new law, emissions will decline instead by a little over 37%. The “most significant legislation in history” will actually cut emissions by less than eight percentage points.

While the administration talks up its emission reductions, it never seems to tout the law’s impact on temperature and sea level—for good reason. If you plug the predicted emissions decline into the climate model used for all major United Nations climate reports, it turns out the global temperature will be cut by only 0.0009 degree Fahrenheit by the end of the century. This is assuming the law’s emission reductions end when its funding does after 2030. But even if you charitably assume they’ll somehow be sustained through 2100 without any interruption, the impact on global temperature will still be almost unnoticeable, at 0.028 degree Fahrenheit.

…..

The cost of the act also belies the oft-repeated claim that green technologies are already cheaper than fossil-fuel alternatives. If they were, they wouldn’t need enormous subsidies. If green energy is going to work, it needs to be as reliable and cheap as fossil fuels. Otherwise developing nations in particular aren’t going to switch to cleaner energy, preferring instead to focus on development and prosperity.

Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 304 of my colleague Peter Boettke’s 2021 paper “Liberalism, Socialism, and Our Future,” as this essay appears as the Conclusion to Pete’s excellent 2021 book, The Struggle for a Better World:

True liberal radicalism, as we have stressed, was born in the struggle for emancipation from dogma, from subjugation, from violence, from poverty. The goal was to find the set of institutions that would minimize human suffering and maximize the opportunities for human flourishing – a system that could empower and grant freedom to all, rather than a select few. The liberal plan of equality, liberty, and justice would deliver autonomy, prosperity, and peace.

DBx: Pictured here is Richard Cobden, who clearly saw – and emphasized – the positive connection between free markets, including of course free trade, and peace.

August 23, 2022

Arnold Kling on Superabundance

Although himself no doomsayer about the environment, Arnold Kling is unpersuaded by a key argument advanced by Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley in their new book, Superabundance.

Over a year ago I read – and enjoyed – the manuscript of what is now published as Superabundance. I’ve not, however, as yet seen the published book, so I can’t comment with any confidence on any of the details about what is or isn’t in the final version. But Arnold’s description of the parts of the book that are relevant for his critical assessment strikes me as accurately representing the book as I recall it.

Arnold’s criticism of Superabundance, if I understand it correctly, has two parts. The first is that Tupy and Pooley pay too little attention to the role played in commodity markets by speculators – and, hence, too little attention to the changes that speculators bring about through time in commodity prices. Arnold concludes from this fact that Tupy’s and Pooley’s comparisons of commodity-price changes through time to changes in the nominal wages of ordinary workers do not reveal what Tupy and Pooley believe these comparisons to reveal.

Tupy and Pooley find that, at least generally, the trend is for nominal commodity prices to fall relative to nominal wages, thus indicating that – at least compared to labor – most commodities are becoming more abundant.

I will not here defend Tupy and Pooley on this narrow point. Arnold’s criticism might well be devastating. I have to ponder further. Yet my initial reaction to this criticism issued by Arnold is that I don’t see that it undermines Tupy’s and Pooley’s point. If over time commodity prices are falling relative to wages, commodities are becoming more abundant relative to human labor (meaning, of course, more affordable by workers). It’s unclear to me why recognition of the vital role of speculators undermines this point.

Again, the fact that Arnold’s point here is unclear to me now doesn’t mean that I’ll not sooner or later come to see its validity.

The second part of Arnold’s criticism strikes me as more fundamental. This second point is that that Tupy and Pooley ignore the fact that many commodities, such as petroleum, are exhaustible. I believe that here Arnold’s criticism is mistaken – or, at least that in issuing this criticism Arnold misses the Julian-Simon point that is central to Tupy’s and Pooley’s project.

Julian Simon argued that the ultimate resource is human creativity. Hence, it is human creativity that creates resources out of the atoms and molecules mashed together in countless combinations by nature. Petroleum, for example, isn’t a resource “naturally.” It is a resource only because and insofar as human creativity has figured out both how to transform it into products useful to humans, and how to make it worthwhile for humans to perform this transformation.

If Simon is correct (as I believe him to be), then the very idea of an exhaustible resource is suspect. Given enough scope to operate, markets – most importantly the price system – will incite entrepreneurs to find new resources as the ‘need’ (that is, as consumer demand) for such resources arises or rises.

Within free markets, this Simon-esque process can be thought of as operating in two related ways. First, as the price of some particular ‘natural’ resource rises, entrepreneurs have incentives to explore for more of it and to tap more of the known deposits of it. (A similar outcome occurs when there is an exogenous fall in the costs of exploration or extraction.) Second, as the price of some ‘natural’ resource rises, entrepreneurs have increased incentives to find less-costly substitutes for that particular ‘natural’ resource.

I think that these two different effects of rises in ‘natural’-resource prices ultimately boil down to being the same thing. What motorists, for example, care about is having fuel for their automobiles. That the fuel is refined from petroleum or from pig waste is ultimately of no concern to motorists. So while it might make sense to talk of some particular mash-up of molecules (for example, petroleum) as an exhaustible resource, if we broaden the category to ‘sources of fuel,’ exhaustibility becomes doubtful, at least as a practical matter.

But even if we confine the discussion to a particular mash-up of molecules (again, for example, petroleum), I believe that the concept of exhaustibility is, at least in many case, less applicable than it seems. Suppose that pictures from the James Webb space telescope were to reveal evidence that large quantities of petroleum exist on Venus. Would this discovery of petroleum on Venus change the quantity of petroleum that is relevant for stating the limits to us humans of petroleum’s exhaustibility?

The tempting answer is ‘no’ because we today have nothing close to economically available techniques for tapping into Venus’s petroleum. But surely we in 2022, who can look back on a few centuries of truly stunning innovation, ought not rule out the possibility that such techniques will one day become available. And if and when the day comes that it does pay humans to extract petroleum from the surface of Venus, then everyone – including even the champion doomsayer Paul Ehrlich – would have to agree that what was thought of in 2022 as the physical limit that defined the supply of petroleum would no longer define that limit.

Obviously, the petroleum-on-Venus example is extreme. But this extremeness is a feature not a bug. At some point not too terribly long ago (let me say, to be safe, 1922) the idea of extracting oil from solid rock would likely have appeared to be as pie-in-the-sky as is the idea of extracting petroleum – or, importantly, some other source of energy – from another heavenly orb. Yet today we economically extract oil from solid rock.

In short, I believe that if we take Julian Simon seriously, Harold Hotelling’s (and other economists’) model of exhaustible resources has only very limited applicability to reality.

……

Two other points. First, Julian Simon is sometimes interpreted as saying that human ingenuity overcomes scarcity in the sense of allowing humans to escape its grip. But this interpretation is mistaken. “Overcomes scarcity” is an ambiguous term. Simon argued that human ingenuity reduces scarcity’s bite – that it makes many scarce goods less scarce. Simon did not argue – and would never have argued – that human ingenuity does, or will eventually, eliminate scarcity.

Second small point: Arnold mentions that the work-time price of the most expensive ticket to a St. Louis Cardinals’ baseball game is today far higher than was the work-time price of the most-expensive ticket to a St. Louis Cardinals’ baseball game in 1966. My guess as to the reason for this reality is that the difference in the quality separating the best seats from the lowliest bleachers is today far greater than it was in the mid-1960s. If my guess is correct, what counts today as top accommodations for spectators in sports stadia is a high-quality good that simply didn’t exist in the mid-1960s. But, as I say, I here only guess.

Russell Roberts's Blog

- Russell Roberts's profile

- 39 followers