Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 47

June 3, 2013

After Earth: What Was Will Smith Thinking?

Columbia Pictures Will Smith's movie After Earth filmed with is son is really getting beat up in the press. Our own Chris Orr, looks into "Will Smith Inc." and comes out horrified:

Columbia Pictures Will Smith's movie After Earth filmed with is son is really getting beat up in the press. Our own Chris Orr, looks into "Will Smith Inc." and comes out horrified: These manifold shortcomings might recede in importance if After Earth had a compelling protagonist at its center. But it doesn't. The younger Smith is persuasive enough--at times perhaps a bit too persuasive—in his portrayal of an awkward, tentative adolescent, but he is entirely lacking in the big-screen charisma that made his father one of Hollywood's major stars.Reading this, I can't stop wondering what, precisely, Will Smith was thinking. I don't want to parent anybody else's kid, but I am trying to imagine myself at 16, put on a stage before the world, and universally panned. One way to think about this is to consider that Will Smith has basically been on stage since high school. But this is not hip-hop back in 1988, with only a few outlets covering the music. This is you stretched out in the street, and the full weight of the internet leaping on you with both feet. And it happens with the backdrop of your Dad being a mega-star. I don't know. If I were famous, I think I'd hide my kids away somewhere--or break out the blanket like Michael Jackson. On the plus side, Chris says that After Earth is "no worse" than M. Night Shyamalan's last two films.

Indeed, I'm not sure I've ever seen a film in which the text and subtext--both concerning an effortlessly gifted father who presses his less-talented son to follow in his footsteps--were so completely in alignment. Alas, only in one of the two does the story end happily.

May 30, 2013

The Conservative Case for Doing Nothing About the Wealth Gap

I mentioned in the comment thread below that I could see a conservative reading this and thinking "This sounds like a great case against expansive government." On that note, here is something else worth considering -- segregation, which is the root of at the root of the wealth gap, is actually on the decline.

Here are two papers that you should read. The first comes out of The Manhattan Institute and is little too optimistic in proclaiming an "end" to segregation. But the paper is still correct in noting a positive trend away from hypersegregation.

The other paper is co-authored by Douglass Massey who, for my money, has written the most clarifying book in the poverty canon on the nature of the black ghetto -- American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. (It contains the best critique I've seen of William Julius Wilson's work.) Massey, whose book was pretty pessimistic, generally concurs that black hypersegregation is declining.

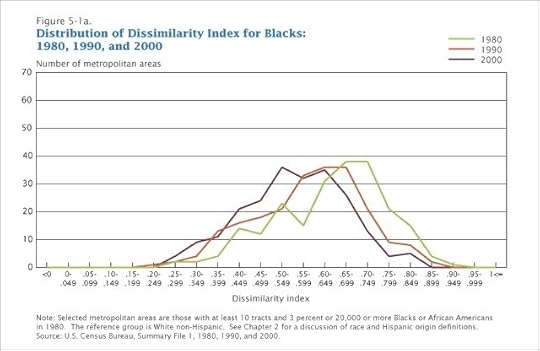

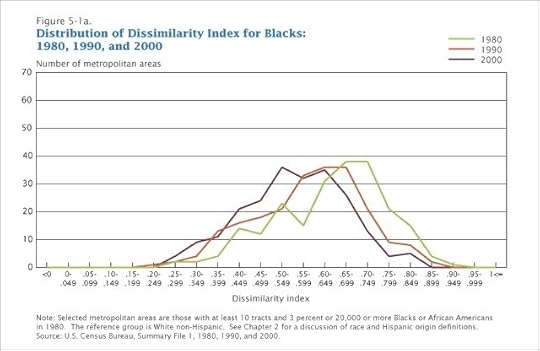

Before we get into this, here is a little math. (Yes, math. From me.) The main tool social scientists use to understand segregation is called the "Dissimilarity Index." (I am going to call it DI here.) What this basically measures is the percent of people in a group who would have to move to a different area (ethnically, racially, economic, whatever you are measuring) to achieve what social scientists call "evenness." Evenness means an "even" distribution of a group across a particular area -- that is to say a population proportionately represented in every micro-area (say census tracts) at the same level they are represented in the macro-area (say, a city). Evenness is measured on a scale of 0 to 1.0. Since black people represent something like 15 percent of the American population, to achieve perfect "evenness" -- or a DI of 0 -- we would have to be 15 percent of every American state.

Here is another way to think of it: You have a city is which is 40 percent black, and you want to know what percent of black people would have to move to make every neighborhood in the city 40 percent black, which would be perfect evenness (a DI of 0.) If you needed 30 percent of all black people to move, the dissimilarity index would be .3 and it would be .5 if you needed 50 percent to move, and it would be 0 (again perfect DI) if you needed no one to move. You can measure dissimilarity through states, cities, and census tracts. Social scientist generally describe any DI above .6 -- on a tract-level -- as high.

At the dawn of the 20th century the average African-American DI was .6, which is to say it was high -- and then it got much, much worse:

As African Americans increasingly urbanized, however, segregation within cities rose from high to rather extreme levels, with the tract-level dissimilarity between blacks and whites going from an average of .60 in 1900 to .77 in 1970. In many cities levels reached .80 and even .90. No group in the history of the United States has ever experienced such extreme residential segregation, either before or since.

You must remember this paragraph anytime someone tells you that the black ghettos of Chicago are "no different" than other white immigrant ghettos. Such a person is speaking in ignorance of the actual math and should be immediately instructed to put down the hair tonic. The black ghettos of America are unlike anything that we have ever seen in this country. And, as we have shown over the past few months, they were the direct result of American policy.

The good news is that it appears that tract-level segregation has actually declined again. Black people are less segregated right now than they've been since the dawn of the 20th century. In one sense that should make you happy. In another sense it should scare you. The "good" news means that black people went not from hypersegregated to integrated, but from hypersegregated to very segregated. Progress. Yay. Still, let's live in the good news for just a moment. If black/white segregation has declined over the past two decades -- and it has -- can we not assume that it will continue to decline on its own?

Massey argues that ultimately segregation is at the root of most of the social ills affecting black people, because it concentrates all of the problems of poverty on the shoulders of one group -- whether everyone in that group is poor or not. To recap, the black poor are not evenly distributed in the way that, say, the daughters or sons will be evenly distributed. Thus black people -- poor or not -- will suffer higher exposure to poverty than white people.

But this is less true today then it was fifty years ago. Can we extrapolate from that that someday -- if we let things alone -- it won't be true at all? Can we assume that segregation will recede, and racism as a force in politics will recede, and the burdens that come from disproportionate exposure to poverty will recede? And if we assume that, is it just to say to those who are still suffering in highly uneven neighborhoods, "We are sorry, but it will be better for your kids, even better for your grandkids, and truly American for your great-grandkids?" Is this just? And just or not, is it in fact, wise?

I offer no conclusions or answers. But you should read those two papers. It's all very, very fascinating.[image error][image error][image error]

The Conservative Case For Doing Nothing About The Wealth Gap

I mentioned in the comment thread below that I could see a conservative reading this and thinking "This sounds like a great case against expansive government." On that note, here is something else worth considering--segregation, which is the root of at the root of the wealth gap, is actually on the decline.

Here are two papers that you should read. The first comes out of The Manhattan Institute and is little too optimistic in proclaiming an "end" to segregation. But the paper is still correct in noting a positive trend away from hypersegregation.

The other paper is co-authored by Douglass Massey who, for my money, has written the most clarifying book in the poverty canon on the nature of the black ghetto--American Apartheid: Segregation and The Making of The Underclass. (It contains the best critique I've seen of William Julius Wilson's work.) Massey, whose book was pretty pessimistic, generally concurs that black hypersegregation is declining.

Before we get into this, here is a little math. (Yes math. From me.) The main tool social scientist use to understand segregation is called the "Dissimilarity Index" (I am going to call it DI here.) What this basically measures is the percent of people in a group who would have to move to a different area (ethnically, racially, economic, whatever you are measuring) to achieve what social scientists call "evenness." Evenness means an "even" distribution of a group across a particular area--that is to say a population proportionately represented in every micro-area (say census tracts) at the same level they are represented in the macro-area (say, a city.) Evenness is measured on a scale of 0 to 1.0. So black peopler represent something like 15 percent of the American population to achieve perfect "evenness"--or a DI of 0--we would have to be 15 percent of every American state.

Here is another way to think of it: You have a city is which is 40 percent black, and you want to know what percent of black people would have to move to make every neighborhood in the city a 40 percent black, when would be perfect Evenness (A DI of 0.) If you needed 30 percent of all black people to move, the dissimilarity index would be .3 and it would be .5 if you needed 50 percent to move, and it would be 0 (again perfect DI) if you needed no one to move. You can measure dissimilarity through states, cities, and census tracts. Social scientist generally describe any DI above .6--on a tract-level--as high.

At the dawn of the 20th century the average African-American DI was .6, which is to say it was high--and then it got much, much worse:

As African Americans increasingly urbanized, however, segregation within cities rose from high to rather extreme levels, with the tract-level dissimilarity between blacks and whites going from an average of .60 in 1900 to .77 in 1970. In many cities levels reached .80 and even .90. No group in the history of the United States has ever experienced such extreme residential segregation, either before or since.

You must remember this paragraph anytime someone tells you that the black ghettoes of Chicago are "no different" than other white immigrant ghettoes. Such a person is speaking in ignorance of the actual math and should be immediately instructed to put down the hair tonic. The black ghettoes of America are unlike anything that we have ever seen in this country. And as we have shown over the past few months they were the direct result of American policy.

The good news is that it appears that tract-level segregation has actually declined again. Black people are less segregated right now than they've been since the dawn of the 20th century. In one sense that should make you happy. In another sense it should scare you. The "good" news means that black people went not from hypersegregated to integrated, but from hypersegregated to very segregated. Progress. Yay. Still let's live in the good news for just a moment. If black/white segregation has declined over the past two decades--and it has--can we not assume that it will continue to decline on its own?

Massey argues that ultimately segregation is at the root of most of the social ills affecting black people, because it concentrates all of the problems of poverty on the shoulders of one group--whether everyone in that group is poor or not. To recap, the black poor are not evenly distributed in the way that, say, the daughters or sons will be evenly distributed. Thus black people--poor or not--will suffer higher exposure to poverty than white people.

But this is less true today, then it was fifty years ago. Can we extrapolate from that, that someday--if we let things alone--it won't be true at all? Can we assume that segregation will recede, and racism as a force in politics will recede, and the burdens that come from disproportionate exposure to poverty will recede? And if we assume that, is it just to say that those who are still suffering in highly uneven neighborhoods, "We are sorry, but it will be better for your kids, even better for your grandkids, and truly American for your great-grandkids?" Is this just? And just or not, is it in fact, wise?

I offer no conclusions or answers. But you should read those two papers. It's all very, very fascinating.

A Religion of Colorblind Policy

The effect is much worse when you consider that the African-American community is hyper-segregated. You have to imagine a state like Mississippi, where the majority of the uninsured are going to be black and the black uninsured will be then mostly concentrated in black neighborhoods. In other words it will be other black people -- uninsured and not -- who will bear the entire social costs of this.

Here is one way to think about this: You are black. You have gotten your college degree and a decent job. But your younger brother isn't doing so well in school and needs some tutoring. And you're worried about your grandmother because her neighborhood isn't safe. And your homeboy, whom you were raised with, just finished a bid for intent to distribute. And your homegirl had a kid when she was 15, but the father is out.

You have made it out of a poor community, but your network is rooted there and shows all the markers of exposure to poverty. Because of a history of American racism, your exposure will be higher than white people of your same income level. Perhaps you would like to build another network. That network, because of a history of racism, will likely be with other black people -- black people who, like you, are part of network that, on average, shows greater exposure to poverty. Meanwhile, white people are building other networks that are significantly less compromised by exposure to poverty.

This is how segregation compromises the power of black community. It takes a societal ill -- say a lack of insurance -- and then concentrates it one community. Members of the whole community, uninsured and not, feel the effects of this to varying degrees, and a problem that is truly American somehow becomes "black." The black uninsured of Mississippi -- a majority of the uninsured of the state -- are not going to be evenly distributed among the various networks of the state. They are going to be concentrated in one particular network.

What the state won't cover, private citizens must. Those citizen will tend to be black. The people who will have to drain their savings will be black. The people who will take out second mortgages will be black. The people who will pick up second jobs (if they can even get them) and miss parenting time will be black. You can multiply this out across social policy, and see how a wealth gap might be perpetuated. No fried chicken jokes required.

How does such a policy come to be? Whom should we blame? Here is one objection worth considering:

I still don't understand how the health law illustrates a shortfall of "color-blind" policies targeting the poor. The demographic numbers in the article show that when Obamacare more generally targeted poor people, it was hugely beneficial to blacks and Latinos. It was only when the Supreme Court shifted it from "lift all boats" to letting states decide whether to lift or sink all boats, did people of color start getting screwed.I think we need to be clear about a few things. Policy does not end after the president signs the law. The courts are part of policy. Brown v. Board struck down segregate schooling. That is part of policy. Plessy v. Ferguson laid the groundwork for Jim Crow. That was policy. So the Supreme Court decision to give states an out is not some separate deux ex machina. This is part of the process, and lawmakers constantly think about, and strategize around, how they believe the courts will see their actions.

In other words, Obamacare doesn't show that black and brown people will be disproportionately among the screwed over when policies "simply target the poor"-- it shows black and brown people will be disproportionately among the screwed over when policies shift power to the states.

The second thing we need to be clear on is that, in our system, the interests of the states have always played an integral role in how we set social policy, often to the detriment of black people. Ira Katznelson's book When Affirmative Action Was White has a brilliant chapter on how the G.I. Bill -- a colorblind, "lift all boats" policy -- actually perpetuated the wealth gap. How was this accomplished? Here is Katznelson:

To be sure, as a national program for all veterans, the GI Bill contained no clauses directly or indirectly excluding blacks or mandating racial discrimination. Even the NAACP's director of the Office of Veterans Affairs, Frank Dedmon, believed that "the VA administers the law as passed by Congress to both Negro and White alike."59 But it was, as Frydl acutely observes, "a congressionally federalized program -- one that was run through the states, supervised by Congress; one central policy making office and hundreds of district offices bounded, in a functional as well as political way, by state lines."

Operating in this manner, she notes, the "exclusion of black veterans came through the mechanisms of administration," and this "flexibility that enabled discrimination against black veterans also worked to the advantage of many other veterans." In this aspect of affirmative action for whites, the path to job placement, loans, unemployment benefits, and schooling was tied to local VA centers, almost entirely staffed by white employees, or through local banks and both public and private educational institutions. By directing federal funding "in keeping with local favor," the veteran status that black soldiers had earned "was placed at the discretion of parochial intolerance."

We should understand where the G.I. Bill stands in the American imagination. Bill Clinton calls it "raised the entire nation to a plateau of social well being never before experienced in U.S. history." It is also a law that Katznelson persuasively argues "widened the country's wealth gap."

I'd be shocked if Obamacare did that, and I don't think it will -- at least not nationally. But my point is that the problems of ostensibly "racism-free" policy devolving into something else is not unique to Obamacare, nor unique to Barack Obama -- and those problems, themselves, are not "racism-free." You can't understand a "states' rights" solution without understanding slavery, Jim Crow and the actual implementation of the New Deal. There are probably very good political reasons -- necessary reasons, even -- for why we attempted to expand insurance through Medicaid. But unless we do something radically different, those reasons will always be dogged by the racism which extends from our roots to our leaves.

And you need not be a "bad person" for this to take effect. All you need do is hold to a religion of "lifting all boats" and ignore the actual science of the sea. All you need do is start paying your taxes under the belief that this will make your prior years, and the interest accrued, magically disappear.

May 29, 2013

The Yeah Yeah Yeahs' Lovely and Creepy Mosquito

Sergio Garcia's Accidental Racism

"The little boy is driving it well, he's putting well," Zoeller told reporters, adding, "You pat him on the back and say congratulations and enjoy it and tell him not to serve fried chicken next year." He then walked away, but turned back and said, "Got it? Or collard greens or whatever the hell they serve."When confronted, Zoeller—despite the "Whatever the hell they serve" tell—was shocked to find people suspecting that he might have said something racist, lamenting that "something I said in jest was turned into something it's not." Some years later we find Sergio Garcia making another fried-chicken joke about Woods and surprised to find himself accused of racism:

I answered a question that was clearly made towards me as a joke with a silly remark, but in no way was the comment meant in a racist manner.Garcia has since gone on an apology tour, all the while declining to say that he made a racist joke. Ian Crouch has a good piece up on how bigoted remarks follow people and why:

On Wednesday, Garcia held a news conference, during which he offered another apology, and attempted to explain himself: "As soon as I left the dinner, I started getting a sick feeling in my body. I didn't really sleep at all. I felt like my heart was going to come out of my body. I've had this sick feeling all day." Part of Garcia's "sick feeling" must surely, if we are to take him at his word, stem from his regret at offending people—though his claim that he felt swiftly guilty does undercut the argument that he was unaware of the racial connotations of the reference. That visceral, sudden sinking feeling also suggests something else: that Garcia, a veteran global sports celebrity, knew almost instantly that his offensive words were something that would very likely remain with him for the rest of his career and beyond, regardless of the passing of time and the force or number of subsequent apologies.One reason the comment will dog Garcia is because he will never cop to what he actually did. In certain eyes (mine) Ron Paul will always be the dude who would countenance white supremacy as long as it advanced him politically, and (much worse) lacked the courage to confront this fact. Crouch contrasts Garcia with Tim Hardaway, who did exactly that:

Many of the stories (mine included) that noted Collins's bravery pointed to the negative things that former player Tim Hardaway had said in 2007 about the prospect of gay players in professional basketball. Hardaway later apologized. But unlike some athletes who do only what they have to in order to save what they can of their careers, his was not just the compulsory apology. He went on to work with gay-rights groups, to learn why what he said was wrong and to make a real effort to atone for it. He had undergone, as he said in 2011, a true "change of heart." Recently, he told the Palm Beach Post, "What I did say was terrible, and it was bad and I live with it every day. It was like a bully going to beat up people every day." And in April, he reached out to Collins and offered him his support. Now, when gay athletes come out of the closet, there will be a sentence about Hardaway and what he said—but below that, there will be another, about what he has done, and said, since. His cruel statements cannot, and should not, be erased, but they mean something different today than they did then.One reason people do not want to cop to bigotry is simply because of the shame. We consider bigotry through the lens of morality. I think this approach is unhelpful as it declines to confront that fact that bigotry exists for actual reasons beyond being "you are a meanie." But be that as it may, no one wants to be shamed. And worse, they don't want to have to do, as Tim Hardaway did, any actual work. Admission is actually only the first step. Its the having to actually do something about it that hurts.

Health Care and Social Justice

Starting next month, the administration and its allies will conduct a nationwide campaign encouraging Americans to take advantage of new high-quality affordable insurance options. But those options will be unavailable to some of the neediest people in states like Texas, Florida, Kansas, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia, which are refusing to expand Medicaid.I want to preface what I am about to say by pointing out the obvious -- the ACA is a great thing. I suspect it will go down as the president's greatest achievement and probably the best thing he's done to fight income inequality.

More than half of all people without health insurance live in states that are not planning to expand Medicaid. People in those states who have incomes from the poverty level up to four times that amount ($11,490 to $45,960 a year for an individual) can get federal tax credits to subsidize the purchase of private health insurance. But many people below the poverty line will be unable to get tax credits, Medicaid or other help with health insurance.

With that said, if you look at a map of which states are refusing the Medicaid expansion, and then look at this report from the Urban Institute, a troubling (if predictable) trend emerges. Approximately a fifth (about 18 percent) of all people who will remain untouched by the Medicaid expansion are black. When you start drilling down to the states where those black people tend to live, it gets worse. In Virginia and North Carolina, 30 percent of those who are going to miss out are black. In South Carolina and Georgia, the number is around 40 percent. In Louisiana and Mississippi, you are talking about 50 percent of those who would be eligible for the expansion but who will go uncovered.

You look at Latinos and get a similar (and to some extent worse) picture. Nationally, Latinos make up 18 percent of those who stand to get health coverage. But in Arizona -- where the legislature is fighting Jan Brewer's effort to expand Medicaid -- Latinos make up 34 percent of those who stand to gain coverage. In Florida, they make up 27 percent, and in Texas they make up 47 percent. Texas has the highest rate of uninsured in the country. The majority of people there who are going to miss out on care -- over 60 percent -- are black and Latino.

This is one reason why color-blind -- "lift all boats" -- policy so often falls short. When you have a country grappling with the deep vestiges of bigoted policy, you do not need "colored only" signs to get "colored mostly" effects.

May 23, 2013

Race, Intelligence, and Genetics For Curious Dummies

Last week there was some debate acros the blogosphere about Race and IQ (again) much of springing from the controversy of Jason Richwine's dissertation--"IQ and Immigration Policy." You can read my thoughts here, here and here. One helpful critique made of these posts by Razib Khan held that they could use more science. Razib added some of that in his own post which was rooted in this paper--"Characterizing The Admixed African Ancestry of African Americans."

I read the paper, understood most of it, but was basically lost trying to understand the graphs. (It's true that my math and science foundation is fairly weak.) So I read it again. Still not quite getting it, I reached out to one of the authors--geneticist Neil Risch, who directs the Institute for Human Genetics at University of California San Francisco. Professor Risch agreed to chat with me via e-mail. He also sent me these two papers("The Importance Of Race And Ethnic Background in Biomedical Research" and "Assessing Genetic Contributions To Phenotypic Differences Among 'Racial' and 'Ethnic' Groups") which I found enlightening and would urge everyone to read.

I want to thank Professor Risch for his time. Our conversation is below.

Thanks for agreeing to talk with me Professor Risch. I've been involved in a good number of conversation around race lately--specifically regarding race and IQ. I was referred to a paper you wrote with some co-authors on the African ancestry of African-Americans. My science background is not particularly strong, and I'd like to bring more science (and less humanities) to my readers on this topic.

Let's start with the dumb and simple questions first. In your paper "Characterizing the admixed African ancestry of African Americans," we see a chart (Figure 1) depicting a Principal components analysis of Africans, U.S. Caucasians and African Americans. For the less mathematically literate among us, can you explain what we're seeing?

In reference to Figure 1, there are primarily 2 different types of analysis we used. Both are based on genetic information. As you have probably read, everyone has 23 pairs of chromosomes, 22 of which are autosomes and one pair is the sex chromosomes (X and Y). Most of that sequence (about 3 billion nucleotides) is identical among individuals, but there are millions of locations where people can differ. In our analysis, we focused on about 450,000 of them. Modern technology now allows us to get a pretty good look at DNA sequence variation among individuals.

The two analyses we used were admixture analysis and principal components analysis (PCA). The first figure shows results of both. What we attempted to do in the bar chart (the admixture analysis) was to estimate for each African American in our study, what proportion of their genome derived from different population groups. In this case, we were focusing on potentially different African subgroups, but did not focus on possible European subgroups. In theory, we possibly could also have done the latter, but because the proportion of ancestry in this sample that was from Europe was not large, that would be more challenging. Our ability to do this analysis depends on how much genetic differentiation there has been between the possible ancestral groups included in the analysis (e.g. the Mandenka, Yoruba, San, Mbuti and Biaka, as well as Europeans). I should be clear that these represent current day populations, and are only possible surrogates for the actual ancestral groups.

That differentiation is depicted in the rest of that figure (the dots with population labels) - which was the result of the PCA. In PCA, you define a few variables that explain the most variation in the data (in this case it is the genetic information). It is a data reduction procedure - in other words, to reduce the information in 450,000 genetic markers to just a few variables. Here we present the first two such reduced variables that explain most of the variation. As you can see, the Europeans and Africans are very well separated on the X axis while the African subgroups are well separated on the Y axis. This separation is what allows us to estimate the proportion of ancestry in the African Americans from each of these groups. You will notice that the African Americans (purple triangles) fall on a line between the Yoruba/Mandenka and the Europeans. This indicates that they have mixed ancestry that is both African and European. The broad spread of the purple triangles along the X axis indicates that individual African Americans in this study vary quite a bit in terms of how much of their ancestry is African and how much is European. You can also see that the majority of the African ancestry is Central-West African because of the approach on the X axis towards the Yoruba/Mandenka. If there were a substantial amount of ancestry from the other groups, you would see the line going more horizontally and less to the upper right.

The actual proportions of ancestry are then given in the bar chart. Here again, you can see the varying amount of European ancestry. It is also confirmed in the bar chart that most of the African ancestry is Central-West African.

You can also see in the bar chart that compared to the European ancestry component, there is much less variation in the different African subgroup components of ancestry - in other words, there aren't some individuals who have much more Yoruban ancestry and others that have much more Bantu ancestry. This is why we concluded that it is likely that mating patterns in African Americans probably did not strongly reflect actual origins in Africa. And that is also the reason we concluded that because most African Americans appear to have admixed African ancestry, looking only at a single genetic location (e.g. the Y chromosome or mtDNA, as often done by ancestry companies) gives only a narrow picture of the entire ancestry.

Subsequent figures in the paper pretty much reinforce these conclusions.

OK, so that helps. A lot. Here is another question. I want to know what someone with your background thinks about the notion of "race." As a writer, I approach this through the lens of history. I imagine, because of that, I might be missing some things. I want to know, as a geneticist, whether you think of African-Americans as a "race?"

I believe it is inaccurate to refer to African Americans as a race or racial group (much like it is similarly inappropriate to refer to Latinos that way) - unless you move away from the more classical definitions of race. We try to use the term race/ethnicity. There has been a lot of debate about whether genetic variation in the human population is continuous or discrete. From my view, it is both. This is what makes it challenging to create categories.

One question pops out at me. You indicate some suspicion to referring to African-Americans as a "race" but (in some of your research) you support using "race" in terms of collecting med data and disease studies. Is this a case of a definition--though it may be imperfect, clunky and at times even misleading--still telling us something, From what I gathered from those articles "race" can be a proxy not just for genetic stuff, but for social phenomenon too (such as access to health care.) Am I seeing that right? Is it correct to say, for instance, "Yes race is a social construct, but this does not make it meaningless." It still useful to look at "race." for instance, when studying sickle-cell. Perhaps some day, when we have more refined technique, it won't be.

Definitions can indeed be "clunky." I would use the phrase race/ethnicity rather than just race because in common parlance it is a better description. I tend to think that race has been used more in terms of continental origins (Africa, East Asia, Europe, Americas). On that basis, one would not characterize African Americans as a racial group, but rather as an ethnic group. We sort of implied this in the Genome Biology paper. The reason is that African Americans typically have European as well as African ancestry (and possibly other ancestries as well) and are also culturally distinct from Africans. Sort of similar to Latinos - who from a genetic ancestry standpoint can be nearly anything. Hence our use of race/ethnicity.

Just to opine a bit, I think part of the problem is the notion of a causal relationship--I.E. "dark-skin" or "blackness" causing sickle-cell, as opposed to a more geographic definition that might encompass people regardless of dark-skin.

Yes, exactly. Groups living in isolation from each other for long periods of time have acquired many genetic differences. The large majority of those are due to "genetic drift" - i.e. random fluctuations in gene frequencies. That also includes many genetic variants that code for traits and diseases. But then there are some genetic variants that differ in frequency due to differential selection pressure in different environments. The best examples are for genes that confer resistance to malaria. One of those causes sickle cell disease in those who carry two mutations; those who carry one copy have sickle cell trait, which is generally benign but confers greater resistance to severe malaria infection. Mutations for sickle cell disease are found at pretty high frequency in some African populations, but also found in parts of the middle east and India. Beta thalassemia is another disease where carriers are offered greater protection from malaria. This disease is more common around the Mediterranean (e.g. Greeks).

Then there is G6PD deficiency. Mutations for that are found at increased frequency in parts of Africa, but also in the Middle East. The mutations underlying these disorders generally differ geographically, which is another indication that while the mutations are different ancestrally, they achieved high frequency in different populations for similar reasons (i.e. resistance to malaria). Another more recent example is a gene called ApoL1. There are a couple of genetic variants found in West Africans (and African Americans); when carrying two of these, there is an increased risk for kidney disease if hypertensive. It was shown that these variants likely provide some immunity from African Sleeping Sickness (tsetse fly disease) which may have led to them becoming more common where the disease is prevalent.

Various populations have an increased frequency of genetic diseases, which are often unique. Probably a lot or most of it is just chance, but perhaps not all of it. Proving historical selective advantages can be pretty challenging. So, as I mentioned above, groups living in isolation developed their own genetic (and cultural) profiles. Generally, there is no cause and effect between the traits that differentiate groups. East Asians have dark hair and eat with chopsticks. But there is no causal relationship. You can use a whole variety of different traits to place individuals into the same categories, but those traits may have nothing to do with each other etiologically.

I often hear people say that Africa has the highest genetic diversity in the world. What does that practically mean?

If you sequence the genome of an African individual (pretty much from anywhere except North Africa), you will generally find more locations in their DNA that are variable than for any non-African individual. Why is this the case? Population geneticists believe that the world outside of Africa was initially populated by humans who migrated out of Africa. The presumption is that if the number of such individuals migrating was small, then some of the genetic variation was lost in the process. As I described before, genetic drift (fluctuation in allele frequencies) can happen when a population is small. The random fluctuation means that some alleles increase in frequency and others decrease. The ones that decrease may be lost altogether. You tend to find that the amount of genetic variation decreases along the migration routes out of Africa (more or less by distance from Africa, but of course population bottlenecks can also happen anywhere along the way).

What is the impact of this? As I mentioned before (and above), random fluctuations in allele frequencies can mean that rare alleles that create risk for a disease may increase in frequency, by chance. So some diseases may become more common. But the flip side is that some diseases may also become less common.

One last question. Your paper on assessing genetic contributions to phenotype, seemed skeptical that we would ever tease out a group-wide genetic component when looking at things like cognitive skills or personality disposition. Am I reading that right? Are "intelligence" and "disposition" just too complicated?

Joanna Mountain and I tried to explain this in our Nature Genetics paper on group differences. It is very challenging to assign causes to group differences. As far as genetics goes, if you have identified a particular gene which clearly influences a trait, and the frequency of that gene differs between populations, that would be pretty good evidence. But traits like "intelligence" or other behaviors (at least in the normal range), to the extent they are genetic, are "polygenic." That means no single genes have large effects - there are many genes involved, each with a very small effect. Such gene effects are difficult if not impossible to find. The problem in assessing group differences is the confounding between genetic and social/cultural factors. If you had individuals who are genetically one-thing but socially another, you might be able to tease it apart, but that is generally not the case.

In our paper, we tried to show that a trait can appear to have high "genetic heritability" in any particular population, but the explanation for a group difference for that trait could be either entirely genetic or entirely environmental or some combination in between.

So, in my view, at this point, any comment about the etiology of group differences, for "intelligence" or anything else, in the absence of specific identified genes (or environmental factors, for that matter), is speculation.

May 22, 2013

Sick Day

And then you should talk about whatever you want--including but not limited to the fact that this is a rather aimless season of Mad Men. Now if you'll excuse me, I have an appointment with some drugs (Nyquil!) I leave you in the capable hands of Sandy and Kathleen.

May 21, 2013

The Myth of the Crack Baby

It is hard to ignore the effects of racism here. There is a time-honored American tradition of turning minorities into the vessel for all the country's vices -- as if adultery, murder, idleness and all other manner of sin would disappear with us. This is especially true in the realm of drugs.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17156 followers