Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 43

June 25, 2013

The Horde and the Supremes

The Horde And The Supremes

Mad Men Season 6 and the Utter Boredom of Moral Plays

AMC

AMC If you have a chance, dip into our Mad Men roundtable for some reflections on this week's episode. Ashley Fetters is feeling dangerously optimistic:

Don's fresh start could be a trickier one. To me, it feels like we've already seen the beginning of the end of Don Draper--not the man himself, but the fake identity Don Draper. We've seen the slick veneer chipping away flashback by flashback all season, and I think on some level, whatever remains of Dick Whitman is growing disgusted with what Don Draper has become. It's almost like it's Don Draper who makes the Hershey pitch, but then it's Dick Whitman who emerges afterward, wanting someone, somewhere to know the truth. Same goes for the scene with Bobby and Sally at the end of the episode. It's the revenge of Dick Whitman. Will Don's downward spiral continue? Potentially. But I saw that last revelation of his childhood home as a good start in the right direction. At the very least, he's taken one step toward being a more honest dad to his kids.

I'm on record saying that I didn't much like this season, but I like how it ended much more than how it began and proceeded. Moreover, looking back it feels this season worked to clear out narrative problems from last season. I would argue that, in terms of storytelling, moving Peggy to another office (if you want to keep her on the show) was a mistake.

In its early years, Mad Men's efficiency was incredible. The show began to (necessarily) sprawl when Don and Betty divorced, and then sprawl even more when Peggy left. I find that a little sad because I generally think the Betty character, and January Jones's performance, are among the highlights of the show. There simply hasn't been a series of scenes between Don and another woman that throbbed with the power of his interaction with Betty leading up to their one-night dalliance. I suspect that is because of the writing--Betty is simply a better developed and more finely detailed character then Megan. But we see less of Betty these days, because she's not central to Don's life. The same fate threatened Peggy. But her return streamlines the world of Mad Men again, and allows the writers to, once again, develop Peggy while developing Stan, Joan, or Ginsburg.

I miss the villain. I miss the Don Draper for whom adultery seemed but the smallest of his sins.

One mistake that remains is substituting in the narrative of an identity thief on the run for a kind of moral redemption play. In this I somewhat disagree with Ashley. I don't find Don Draper's redemption interesting at all. I prefer to think of him in the way that I thought of Ray Milland in Dial M for Murder--a veneer of cool covering a core of panic and desperation. Perhaps it's because television is flush with anti-heroes, and villains who want to do right. These days, everyone is Magneto.

But what was original about Don Draper was that he was a thief--possibly repentant, but not really. That Don Draper understood the ephemeral nature of truth and good breeding. I don't think I've seen a colder scene than Don Draper staring coolly at his brother and effectively telling him to get lost. And I don't know that I've seen a more riveting scene than Draper telling his young Padwan, "This never happened. It will shock you how much it never happened." That was villainy--villainy in service of an accidental feminism, but villainy all the same. I miss the villain. I miss the Don Draper for whom adultery seemed but the smallest of his sins. And I don't need him to be redeemed.

June 24, 2013

The Guileless 'Accidental Racism' of Paula Deen

Paula Deen was born in Southwest Georgia, a portion of our country known for its rabid resistance to the civil rights advancements of the mid-20th century. It was in Southwest Georgia that Martin Luther King joined the Albany Movement. It was in Southwest Georgia that Shirley and Charles Sherrod fought nonviolently for the voting rights that were theirs by law. It was in Southwest Georgia that Shirley Sherrod's cousin, Bobby Hall, was lynched. It was in Southwest Georgia that Shirley Sherrod's father was shot down by a white man. This man was never punished.

A few months ago I was interviewing a gentleman who'd migrated up from the South in the 1930s. When I asked him why he'd left, he said he was looking for "protection of the law." It is crucial that we remember that the South, for black people, was not just the home of "Colored Only" water-fountains, but was a kind of perpetual anarchic terrorist state. There was no law.

For some reason we like to think that members of ruling class raised in such environs remain unaffected, that the brutality which the children witness does not, somehow, work on their morality, their character and bearing. Our forefathers knew better:

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But generally it is not sufficient. The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances.

I confess myself refreshed to hear Paula Deen respond "Yes, of course," when asked if she used the word "nigger." We have conditioned ourselves with a kind of magic to believe that racism is a matter of kindness and prohibitive vocabulary -- as though a hatred of women can be reduced the use of the word "bitch." But what does a country which tolerates the terrorism of Southwest, Georgia expect? What does a country whose left wing's greatest policy achievement was made possible by an embrace of white supremacy really believe will happen to children raised in such times? What do we expect in a country where many find it entirely appropriate to wear the battle-flag of the republic of slavery?

Perhaps it expects that they will be savvy enough to not propose sambo burgers or plantation themed weddings. But this is an embarrassment at airs, not the actual truth. When you watch the video above, note the people cheering and laughing. For those without video, here is what was said:

Deen, talking at an event months before losing her job for using the "N-word," recounted how her great-grandfather was driven to suicide after his 30 slaves were set free. "Between the death of his son and losing all the workers, he went out into his barn and shot himself because he couldn't deal with those kind of changes," Deen said at a New York Times event. Deen, owner of a restaurant empire, asserted the owner-slave relationship was more kinship than cruelty. "Back then, black folk were such an integral part of our lives," said Deen. "They were like our family, and for that reason we didn't see ourselves as prejudiced." She also called up an employee to join her onstage, noting that Hollis Johnson was "as black as this board" -- pointing to the dark backdrop behind her. "We can't see you standing in front of that dark board!" Deen quipped, drawing laughter from the audience. At the same event, Deen at one point described race relations in the South as "pretty good." "We're all prejudiced against one thing or another," she added. "I think black people feel the same prejudice that white people feel."

Here is everything from Civil War hokum to black friend apologia to blatant racism. And people at a New York Times event are laughing along with it.

This morning, I showed this video to my wife. My wife is dark-skinned. My wife is from Chicago by way of Covington, Tennessee. The remark sent her right back to childhood. I suspect that the laughter in the crowd was a mix of discomfort, shock and ignorance. The ignorance is willful. We know what we want to know, and forget what discomfits us.

There is a secret at the core of our nation. And those who dare expose it must be condemned, must be shamed, must be driven from polite society. But the truth stalks us like bad credit. Paula Deen knows who you were last summer. And the summer before that.

The Guileless Accidental Racism Of Paula Deen

Paula Deen was born in Southwest Georgia, a portion of our country known for its rabid resistance to the civil rights advancements of the mid-20th century. It was in Southwest Georgia that Martin Luther King joined the Albany Movement. It was in Southwest Georgia that Shirley and Charles Sherrod fought nonviolently for the voting rights that were theirs by law. It was in Southwest Georgia that Shirley Sherrod's cousin, Bobby Hall, was lynched. It was in Southwest Georgia that Shirley Sherrod's father was shot down by a white man. This man was never punished.

A few months ago I was interviewing a gentleman who'd migrated up from the South in the 1930s. When I asked him why he'd left, he said he was looking for "protection of the law." It is crucial that we remember that the South, for black people, was not just the home of "Colored Only" water-fountains, but was a kind of perpetual anarchic terrorist state. There was no law.

For some reason we like to think that members of ruling class raised in such environs remain unaffected, that the brutality which the children witness does not, somehow, work on their morality, their character and bearing. Our forefathers knew better:

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But generally it is not sufficient. The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances.

I confess myself refreshed to hear Paula Deen respond "Yes, of course," when asked if she used the word "nigger." We have conditioned ourselves on a kind of magic wherein we believe that racism is a matter of kindness and prohibitive vocabulary--as though a hatred of women can be reduced the use of the word "bitch." But what does a country which tolerates the terrorism of Southwest, Georgia expect? What does a country whose left wing's greatest policy achievement was made possible by an embrace of white supremacy really believe will happen to children raised in such times? What do we expect in a country where many find it entirely appropriate to wear the battle-flag of the republic of slavery?

Perhaps it expects that they will be savvy enough to not propose sambo burgers or plantation themed weddings. But this is an embarrassment at airs, not the actual truth. When you watch the video above, note the people cheering and laughing. For those without video, here is what was said:

Deen, talking at an event months before losing her job for using the "N-word," recounted how her great-grandfather was driven to suicide after his 30 slaves were set free. "Between the death of his son and losing all the workers, he went out into his barn and shot himself because he couldn't deal with those kind of changes," Deen said at a New York Times event. Deen, owner of a restaurant empire, asserted the owner-slave relationship was more kinship than cruelty. "Back then, black folk were such an integral part of our lives," said Deen. "They were like our family, and for that reason we didn't see ourselves as prejudiced." She also called up an employee to join her onstage, noting that Hollis Johnson was "as black as this board" -- pointing to the dark backdrop behind her. "We can't see you standing in front of that dark board!" Deen quipped, drawing laughter from the audience. At the same event, Deen at one point described race relations in the South as "pretty good." "We're all prejudiced against one thing or another," she added. "I think black people feel the same prejudice that white people feel."

Here is everything from Civil War hokum to black friend apologia to blatant racism. And people at a New York Times event are laughing along with it.

This morning, I showed this video to my wife. My wife is dark skin. My wife is from Chicago by way of Covington, Tennessee. The remark sent her right back to childhood. I suspect that the laughter in the crowd was a mix of discomfort, shock and ignorance. The ignorance is willful. We know what we want to know, and forget what discomfits us.

There is a secret at the core of our nation. And those who dare expose it must be condemned, must be shamed, must be driven from polite society. But the truth stalks us like bad credit. Paula Deen knows who you were last summer. And the summer before that.

June 21, 2013

Understanding Out-of-Wedlock Births in Black America

I'm still making my way through some of the latest reconsiderations of the Moynihan Report. While doing that I've been thinking a lot about a number you see invoked whenever discussing the state of the black family--70 percent of all births among African-Americans happen out of wedlock. You often see this number invoked to show the moral or cultural decline in the black family:

For African-Americans. That's embarrassing. And you know, in the entire recorded history of the planet, there has never been a greater voluntary abandonment of men from their children than there is today in black America. Never. I mean, when men went off to war, they had to go off to war. That wasn't voluntary. But never as great of voluntary abandonment of children by their fathers than in black America today.

Or like this:

Why don't the NAACP and similar organizations take all the money they use to challenge and complain about the standards that their groups (in the aggregate) don't meet when it comes to university admissions, selective high-school admissions, school discipline, mortgage loans, police and firefighter tests, felon disenfranchisement laws, employment policies that look at criminal records, etc., etc., and use that money to figure out ways to bring down the illegitimacy rates that drive all these other disparities?

Just as often you see it invoked by black people themselves in much the same way. What undergirds all of this is the sense that the black community of today is somehow deficient in a way that the black community of yesteryear was not.

I think its very important to get past the jeremiads and understand why the numbers look the way they do. And given that this is an old beef of mine, I figured I'd go through the numbers again, fool around with some spreadsheets and try to get in touch with my inner Derek Thompson.

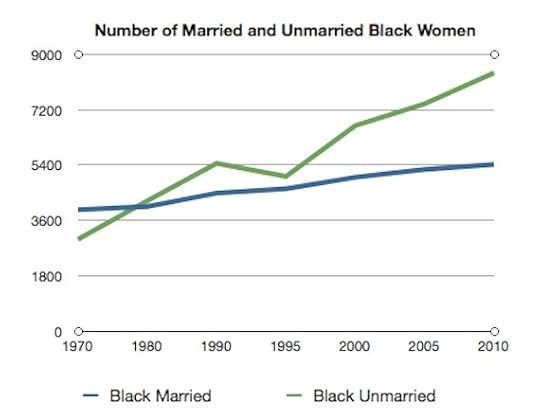

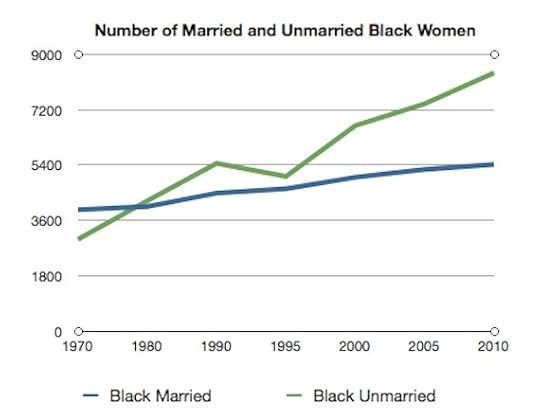

One obvious reason that you have a higher percentage of children born out of wedlock in the black community is that the number of unmarried women (mothers or not) has grown a lot, while number of married women has grown only a little. You can see that in the chart above, which I culled from these census numbers. The numbers are by the thousand.

But while the number of unmarried black women has substantially grown, the actual birthrate (measured by births per 1000) for black women is it the lowest point that its ever documented.*

So while a larger number of black women are choosing not to marry, many of those women are also choosing not to bring kids into the world. But there is something else.

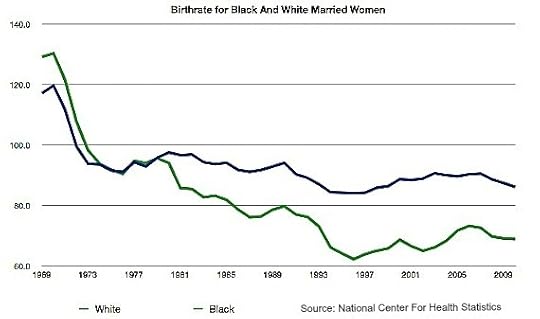

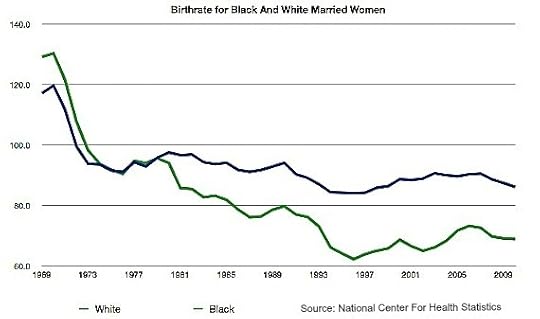

As you can see the drop in the birthrate for unmarried black women is mirrored by an even steeper drop among married black women. Indeed, whereas at one point married black women were having more kids than married white women, they are now having less.

I point this out to show that the idea that the idea that, somehow, the black community has fallen into a morass of cultural pathology is convenient nostalgia. There is nothing "immoral" or "pathological" about deciding not to marry. In the glorious black past, women who made that decision were more--not less--likely to become mothers. People who are truly concerned about the percentage of out of wedlock births would do well to hector married black women for moral duty to churn out babies in the manner of their glorious foremothers. But no one would do that. Because it would be absurd.

Theories of cultural decline are irrelevant. Policy not so much. Given the contact rates between the justice system and young black men, and given how that contact affects your employment prospects, the decision by many black women to not marry, and to have less children, strikes me as logical. If we want to change marriage rates, we need to change our policies. Nostalgia is magic. Policy is the hero.

*I had to call the CDC to get the numbers for married and unmarried. If anyone wants the data, ask in comments and I will get it to you.

Understanding Out Of Wedlock Births In Black America

I'm still making my way through some of the latest reconsiderations of the Moynihan Report. While doing that I've been thinking a lot about a number you see invoked whenever discussing the state of the black family--70 percent of all births among African-Americans happen out of wedlock. You often see this number invoked to show the moral or cultural decline in the black family:

For African-Americans. That's embarrassing. And you know, in the entire recorded history of the planet, there has never been a greater voluntary abandonment of men from their children than there is today in black America. Never. I mean, when men went off to war, they had to go off to war. That wasn't voluntary. But never as great of voluntary abandonment of children by their fathers than in black America today.

Or like this:

Why don't the NAACP and similar organizations take all the money they use to challenge and complain about the standards that their groups (in the aggregate) don't meet when it comes to university admissions, selective high-school admissions, school discipline, mortgage loans, police and firefighter tests, felon disenfranchisement laws, employment policies that look at criminal records, etc., etc., and use that money to figure out ways to bring down the illegitimacy rates that drive all these other disparities?

Just as often you see it invoked by black people themselves in much the same way. What undergirds all of this is the sense that the black community of today is somehow deficient in a way that the black community of yesteryear was not.

I think its very important to get past the jeremiads and understand why the numbers look the way they do. And given that this is an old beef of mine, I figured I'd go through the numbers again, fool around with some spreadsheets and try to get in touch with my inner Derek Thompson.

One obvious reason that you have a higher percentage of children born out of wedlock in the black community is that the number of unmarried women (mothers or not) has grown a lot, while number of married women has grown only a little. You can see that in the chart above, which I culled from these census numbers. The numbers are by the thousand.

But while the number of unmarried black women has substantially grown, the actual birthrate (measured by births per 1000) for black women is it the lowest point that its ever documented.*

So while a larger number of black women are choosing not to marry, many of those women are also choosing not to bring kids into the world. But there is something else.

As you can see the drop in the birthrate for unmarried black women is mirrored by an even steeper drop among married black women. Indeed, whereas at one point married black women were having more kids than married white women, they are now having less.

I point this out to show that the idea that the idea that, somehow, the black community has fallen into a morass of cultural pathology is convenient nostalgia. There is nothing "immoral" or "pathological" about deciding not to marry. In the glorious black past, women who made that decision were more--not less--likely to become mothers. People who are truly concerned about the percentage of out of wedlock births would do well to hector married black women for moral duty to churn out babies in the manner of their glorious foremothers. But no one would do that. Because it would be absurd.

Theories of cultural decline are irrelevant. Policy not so much. Given the contact rates between the justice system and young black men, and given how that contact affects your employment prospects, the decision by many black women to not marry, and to have less children, strikes me as logical. If we want to change marriage rates, we need to change our policies. Nostalgia is magic. Policy is the hero.

*I had to call the CDC to get the numbers for married and unmarried. If anyone wants the data, ask in comments and I will get it to you.

June 20, 2013

No, Lincoln Could Not Have 'Bought the Slaves'

One idea that will not die is the notion that Lincoln could have purchased the slaves freedom and thus avoided the Civil War. This argument ignores many factors. Among them: the fact that slavemasters actually liked being slavemasters and believe their system to be a "positive good." The fact that slavery was a social institution that granted benefits beyond hard cash. The fact that Lincoln tried compensated emancipation in Delaware and was rebuffed. The fact that no state was eager to have a large portion of black free people within its borders. But more than anything the argument ignores the fact that compensated emancipation was not economically possible. At all.

Rather then going through this again, I am reposting something I wrote when Ron Paul was arguing that compensated emancipation somehow would have prevented the Civil War. I do this with some frustration. More than anything, the Civil War has taught me that people often believe what they perceive it to be in their interest to believe. The facts of the Civil War are not mysterious to us. But they are, evidently, too brutal for of us to take. And so we find ourselves into a soloutionism premised on the idea that we are smarter than our forefathers. We are not. The Civil War is a fact. It happened for actual reasons. Those reasons do not change because they make us uncomfortable, nor because we believe in the magic of intellectual cowardice.

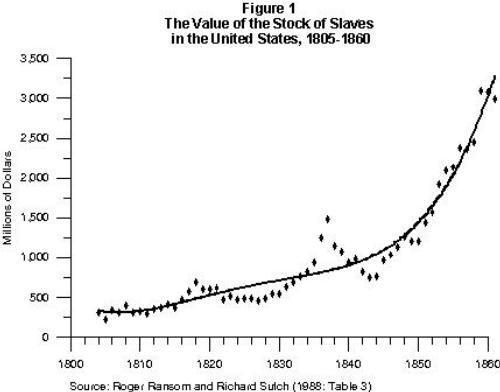

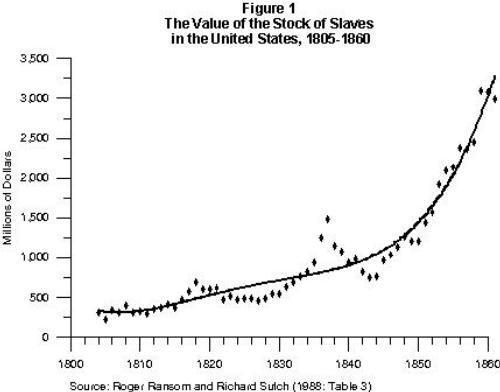

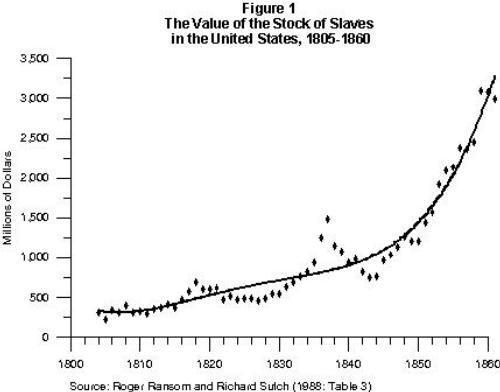

I saw the graph above for the first time yesterday, and it made me shiver. It's taken from historian Roger L. Ransom's article "The Economics Of The Civil War."When you look at how American planters discussed slavery, over time, you find a marked shift. In the late 18th, early 19th century, slavery is is seen as an unfortunate inheritance, a problem of morality lacking a practical solution. Thomas Jefferson's articulation is probably the definitive in this school of thinking:

There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.

In Jefferson's day, talk of eventual abolition was not particularly rare in the South. Slave-owners spoke of colonization and some even emancipated their own slaves, The Quakers had a presence in the South and in the late 18th century banned slave-holding (If anyone has a precise date, I'll gladly insert.) Prominent slave-owning southerners like Henry Clay were in pursuit of some kind of compromise which would purge the country of its birth taint.

But by the 1830s, such thinking was out of vogue in the South. Men like Henry Clay's cousin Cassius Clay, once wrote:

Slavery is an evil to the slave, by depriving nearly three millions of men of the best gift of God to man -- liberty. I stop here -- this is enough of itself to give us a full anticipation of the long catalogue of human woe, and physical and intel- lectual and moral abasement which follows in the wake of Slavery. Slavery is an evil to the master. It is utterly subservient of the Christian religion. It violates the great law upon which that religion is based, and on account of which it vaunts its preemi- nence.

In 1845 Clay was run out of Kentucky by a mob. By then the Calhoun school had taken root and Southerners had begun arguing that slavery was not immoral, but a positive good:

Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually. In the meantime, the white or European race, has not degenerated. It has kept pace with its brethren in other sections of the Union where slavery does not exist. It is odious to make comparison; but I appeal to all sides whether the South is not equal in virtue, intelligence, patriotism, courage, disinterestedness, and all the high qualities which adorn our nature.

But I take higher ground. I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good--a positive good.

This is not just a rebuke of abolitionist thinking, but a rebuke of Jeffersonian thinking. Fifteen years later, Alexander Stephens would call Jefferson out by name arguing that his presumption of equality among men was a grievous error.

Perhaps this is too crude an interpretation but the graph above, measuring the incredible rise in the wealth represented by the pilfering of black labor, tracks directly with the political debate. When slaves were worth only a cool $300 million, property in man was an "unhappy influence." When that number skyrocketed in excess of $3 billion, suddenly it was a "positive good." Perhaps this is to deterministic. I leave it to my fellow commenters to color in the portrait. At any rate the notion that such an interest--by far the greatest collective asset in the country at the time--could be merely incidental to the war is creationist quackery.

But on to the problem.

Ron Paul's argument is essentially that it would have been better for the government to bail out slave-holders by effecting a mass purchase of blacks. This would have saved a lot of money, as well as the lives and limbs of a lot of white people. I do not believe that saving lives and limbs of any people--white or black--to be a disreputable goal. But I refuse to lose sight of the fact that slavery was, itself, war. And the lives and limbs of black people were perpetually at stake for centuries. From 1860 to 1865 the rest of the country received a concentrated dose of that medicine which black people had been made to quaff for over two and a half centuries. It is now a century and a half later, but still in some corners of white America it is fashionable to remain embittered.

Nevertheless, the saving of people is, indeed, a noble goal, and Paul is not without at least the rudiments of a case. Enslaved black people were constructed into an interest representing $3 billion. ($70-75 billion in 21st century money.) But including expenditures, loss of property, loss of life (human capital,) the war, according to Ransom, costs $6.6 billion.

The numbers are clear--the South's decision to raise an army, encourage sedition among its neighbors, and fire on federal property, was an economic disaster for white America. Moreover, the loss of 600,000 lives, in a war launched to erect an empire on the cornerstone of white supremacy and African slavery, was a great moral disaster for all corners of America.

In the most crude sense, it would have been much "cheaper" for the government to effect a mass purchase. But how? Ransom gives us some thoughts:

One "economic" solution to the slave problem would be for those who objected to slavery to "buy out" the economic interest of Southern slaveholders. Under such a scheme, the federal government would purchase slaves. A major problem here was that the costs of such a scheme would have been enormous. Claudia Goldin estimates that the cost of having the government buy all the slaves in the United States in 1860, would be about $2.7 billion (1973: 85, Table 1). Obviously, such a large sum could not be paid all at once. Yet even if the payments were spread over 25 years, the annual costs of such a scheme would involve a tripling of federal government outlays (Ransom and Sutch 1990: 39-42)! The costs could be reduced substantially if instead of freeing all the slaves at once, children were left in bondage until the age of 18 or 21 (Goldin 1973:85). Yet there would remain the problem of how even those reduced costs could be distributed among various groups in the population. The cost of any "compensated" emancipation scheme was so high that even those who wished to eliminate slavery were unwilling to pay for a "buyout" of those who owned slaves.

It is statement on the quality of our journalism, that I have seen Ron Paul repeatedly note that compensated emancipation would have avoided the Civil War, but I never seen a journalist ask him "How?" The "How" is quite clear--either by tripling the federal budget for 25 years, or through the (continued) enslavement of children.

These are all questions from the buyer-side. What about the seller? Would slaveholders willingly sell at "fair" price? How do we decide fair?

Edward Gaffney offers some thoughts in comments:

[A]s a slaveowner, you know that an abolitionist government values slaves more than you. In particular, they don't have a reason to pay lower prices as they buy more slaves. Therefore, the market in slaves breaks down immediately upon the beginning of compensated emancipation. Suddenly, there's a big buyer who will keep on buying. Just like a bond trader, why would you charge a big buyer the liquid market price if you know he's not going to stop buying? You should charge him the highest value of the last slave owned by any slaveowner, at the very least.

This is the theory of the cartel in the economics of industrial organisation. The social apparatus of a slaveholding society should minimise the number of defections from this cartel by easy sellers; in particular, they would fear that one's status would fall if one chooses money while one's neighbours choose to continue owning human beings. Sellers now have the market power; the price rises as a result.

A government which buys slaves, with the explicit intent to buy all slaves, is in a poor bargaining position versus slaveowners.. Signalling your intention to buy up all the supply of a commodity on the market increases the price you'll pay, whether that be bonds or human beings.

The thought-experiment, here, needs to be full gamed out. Ostensibly, in the government you have a buyer which, faced with the threat of mass violence, is willing to pay a large sum to end slavery. In slave-holders you have a seller, that does not want to sell, that has reacted violently to recent talk of selling, that, further, believes slavery is a good thing, ordained by God and the Bible. The greater country--having rejected war as an option--has no ability to compel this seller to any price. On the contrary, the country is, itself, partially dependent on slave-holders. ("By the mid 1830s, cotton shipments accounted for more than half the value of all exports from the United States," writes Ransom.)

How does one make this work? And more importantly, why do we need to?

We are united in our hatred of war and our abhorrence of violence. But a hatred of war is not enough, and when employed to conjure away history, it is a cynical vanity which posits that one is, somehow, in possession of a prophetic insight and supernatural morality which evaded our forefathers. It is all fine to speak of how history "should have been." It takes something more to ask why it wasn't, and then to confront what it actually was.

H/T to Yglesias for much of this post.

No, Lincoln Could Not Have 'Bought The Slaves'

\

One idea that will not die is the notion that Lincoln could have purchased the slaves freedom and thus avoided the Civil War. This argument ignores many factors. Among them: The fact that slavemasters actually liked being slavemasters and believe their system to be a "positive good." The fact that slavery was a social institution that granted benefits beyond hard cash. The fact that Lincoln tried compensated emancipation in Delaware and was rebuffed. The fact that no state was eager to have a large portion of black free people within its borders. But more than anything the argument ignores the fact that compensated emancipation was not economically possible. At all.

Rather then going through this again, I am reposting something I wrote when Ron Paul was arguing that compensated emancipation somehow would have prevented the Civil War. I do this with some frustration. More than anything the Civil War has taught me that people often believe what they perceive it to be in their interest to believe. The facts of the Civil War are not mysterious to us. But they are, evidently, too brutal for of us to take. And so we find ourselves into a soloutionism premised on the idea that we are smarter than our forefathers. We are not. The Civil War is a fact. It happened for actual reasons. Those reasons do not change because they make us uncomfortable, nor because we believe in the magic of intellectual cowardice.

I saw the graph above for the first time yesterday, and it made me shiver. It's taken from historian Roger L. Ransom's article "The Economics Of The Civil War."When you look at how American planters discussed slavery, over time, you find a marked shift. In the late 18th, early 19th century, slavery is is seen as an unfortunate inheritance, a problem of morality lacking a practical solution. Thomas Jefferson's articulation is probably the definitive in this school of thinking:

There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.

In Jefferson's day, talk of eventual abolition was not particularly rare in the South. Slave-owners spoke of colonization and some even emancipated their own slaves, The Quakers had a presence in the South and in the late 18th century banned slave-holding (If anyone has a precise date, I'll gladly insert.) Prominent slave-owning southerners like Henry Clay were in pursuit of some kind of compromise which would purge the country of its birth taint.

But by the 1830s, such thinking was out of vogue in the South. Men like Henry Clay's cousin Cassius Clay, once wrote:

Slavery is an evil to the slave, by depriving nearly three millions of men of the best gift of God to man -- liberty. I stop here -- this is enough of itself to give us a full anticipation of the long catalogue of human woe, and physical and intel- lectual and moral abasement which follows in the wake of Slavery. Slavery is an evil to the master. It is utterly subservient of the Christian religion. It violates the great law upon which that religion is based, and on account of which it vaunts its preemi- nence.

In 1845 Clay was run out of Kentucky by a mob. By then the Calhoun school had taken root and Southerners had begun arguing that slavery was not immoral, but a positive good:

Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually. In the meantime, the white or European race, has not degenerated. It has kept pace with its brethren in other sections of the Union where slavery does not exist. It is odious to make comparison; but I appeal to all sides whether the South is not equal in virtue, intelligence, patriotism, courage, disinterestedness, and all the high qualities which adorn our nature.

But I take higher ground. I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good--a positive good.

This is not just a rebuke of abolitionist thinking, but a rebuke of Jeffersonian thinking. Fifteen years later, Alexander Stephens would call Jefferson out by name arguing that his presumption of equality among men was a grievous error.

Perhaps this is too crude an interpretation but the graph above, measuring the incredible rise in the wealth represented by the pilfering of black labor, tracks directly with the political debate. When slaves were worth only a cool $300 million, property in man was an "unhappy influence." When that number skyrocketed in excess of $3 billion, suddenly it was a "positive good." Perhaps this is to deterministic. I leave it to my fellow commenters to color in the portrait. At any rate the notion that such an interest--by far the greatest collective asset in the country at the time--could be merely incidental to the war is creationist quackery.

But on to the problem.

Ron Paul's argument is essentially that it would have been better for the government to bail out slave-holders by effecting a mass purchase of blacks. This would have saved a lot of money, as well as the lives and limbs of a lot of white people. I do not believe that saving lives and limbs of any people--white or black--to be a disreputable goal. But I refuse to lose sight of the fact that slavery was, itself, war. And the lives and limbs of black people were perpetually at stake for centuries. From 1860 to 1865 the rest of the country received a concentrated dose of that medicine which black people had been made to quaff for over two and a half centuries. It is now a century and a half later, but still in some corners of white America it is fashionable to remain embittered.

Nevertheless, the saving of people is, indeed, a noble goal, and Paul is not without at least the rudiments of a case. Enslaved black people were constructed into an interest representing $3 billion. ($70-75 billion in 21st century money.) But including expenditures, loss of property, loss of life (human capital,) the war, according to Ransom, costs $6.6 billion.

The numbers are clear--the South's decision to raise an army, encourage sedition among its neighbors, and fire on federal property, was an economic disaster for white America. Moreover, the loss of 600,000 lives, in a war launched to erect an empire on the cornerstone of white supremacy and African slavery, was a great moral disaster for all corners of America.

In the most crude sense, it would have been much "cheaper" for the government to effect a mass purchase. But how? Ransom gives us some thoughts:

One "economic" solution to the slave problem would be for those who objected to slavery to "buy out" the economic interest of Southern slaveholders. Under such a scheme, the federal government would purchase slaves. A major problem here was that the costs of such a scheme would have been enormous. Claudia Goldin estimates that the cost of having the government buy all the slaves in the United States in 1860, would be about $2.7 billion (1973: 85, Table 1). Obviously, such a large sum could not be paid all at once. Yet even if the payments were spread over 25 years, the annual costs of such a scheme would involve a tripling of federal government outlays (Ransom and Sutch 1990: 39-42)! The costs could be reduced substantially if instead of freeing all the slaves at once, children were left in bondage until the age of 18 or 21 (Goldin 1973:85). Yet there would remain the problem of how even those reduced costs could be distributed among various groups in the population. The cost of any "compensated" emancipation scheme was so high that even those who wished to eliminate slavery were unwilling to pay for a "buyout" of those who owned slaves.

It is statement on the quality of our journalism, that I have seen Ron Paul repeatedly note that compensated emancipation would have avoided the Civil War, but I never seen a journalist ask him "How?" The "How" is quite clear--either by tripling the federal budget for 25 years, or through the (continued) enslavement of children.

These are all questions from the buyer-side. What about the seller? Would slaveholders willingly sell at "fair" price? How do we decide fair?

Edward Gaffney offers some thoughts in comments:

[A]s a slaveowner, you know that an abolitionist government values slaves more than you. In particular, they don't have a reason to pay lower prices as they buy more slaves. Therefore, the market in slaves breaks down immediately upon the beginning of compensated emancipation. Suddenly, there's a big buyer who will keep on buying. Just like a bond trader, why would you charge a big buyer the liquid market price if you know he's not going to stop buying? You should charge him the highest value of the last slave owned by any slaveowner, at the very least.

This is the theory of the cartel in the economics of industrial organisation. The social apparatus of a slaveholding society should minimise the number of defections from this cartel by easy sellers; in particular, they would fear that one's status would fall if one chooses money while one's neighbours choose to continue owning human beings. Sellers now have the market power; the price rises as a result.

A government which buys slaves, with the explicit intent to buy all slaves, is in a poor bargaining position versus slaveowners.. Signalling your intention to buy up all the supply of a commodity on the market increases the price you'll pay, whether that be bonds or human beings.

The thought-experiment, here, needs to be full gamed out. Ostensibly, in the government you have a buyer which, faced with the threat of mass violence, is willing to pay a large sum to end slavery. In slave-holders you have a seller, that does not want to sell, that has reacted violently to recent talk of selling, that, further, believes slavery is a good thing, ordained by God and the Bible. The greater country--having rejected war as an option--has no ability to compel this seller to any price. On the contrary, the country is, itself, partially dependent on slave-holders. ("By the mid 1830s, cotton shipments accounted for more than half the value of all exports from the United States," writes Ransom.)

How does one make this work? And more importantly, why do we need to?

We are united in our hatred of war and our abhorrence of violence. But a hatred of war is not enough, and when employed to conjure away history, it is a cynical vanity which posits that one is, somehow, in possession of a prophetic insight and supernatural morality which evaded our forefathers. It is all fine to speak of how history "should have been." It takes something more to ask why it wasn't, and then to confront what it actually was.

H/T to Yglesias for much of this post.

No, Lincoln Could Not Have "Bought The Slaves"

\

One idea that will not die is the notion that Lincoln could have purchased the slaves freedom and thus avoided the Civil War. This argument ignores many factors. Among them: The fact that slavemasters actually liked being slavemasters and believe their system to be a "positive good." The fact that slavery was a social institution that granted benefits beyond hard cash. The fact that Lincoln tried compensated emancipation in Delaware and was rebuffed. The fact that no state was eager to have a large portion of black free people within its borders. But more than anything the argument ignores the fact that compensated emancipation was not economically possible. At all.

Rather then going through this again, I am reposting something I wrote when Ron Paul was arguing that compensated emancipation somehow would have prevented the Civil War. I do this with some frustration. More than anything the Civil War has taught me that people often believe what they perceive it to be in their interest to believe. The facts of the Civil War are not mysterious to us. But they are too many of us to take. And so we find ourselves into a soloutionism premised on the idea that we are smarter than our forefathers. We are not. The Civil War is a fact. It happened for actual reasons. Those reasons do not change because they make us uncomfortable, nor because we believe in the magic of intellectual cowardice.

I saw the graph above for the first time yesterday, and it made me shiver. It's taken from historian Roger L. Ransom's article "The Economics Of The Civil War."When you look at how American planters discussed slavery, over time, you find a marked shift. In the late 18th, early 19th century, slavery is is seen as an unfortunate inheritance, a problem of morality lacking a practical solution. Thomas Jefferson's articulation is probably the definitive in this school of thinking:

There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.

In Jefferson's day, talk of eventual abolition was not particularly rare in the South. Slave-owners spoke of colonization and some even emancipated their own slaves, The Quakers had a presence in the South and in the late 18th century banned slave-holding (If anyone has a precise date, I'll gladly insert.) Prominent slave-owning southerners like Henry Clay were in pursuit of some kind of compromise which would purge the country of its birth taint.

But by the 1830s, such thinking was out of vogue in the South. Men like Henry Clay's cousin Cassius Clay, once wrote:

Slavery is an evil to the slave, by depriving nearly three millions of men of the best gift of God to man -- liberty. I stop here -- this is enough of itself to give us a full anticipation of the long catalogue of human woe, and physical and intel- lectual and moral abasement which follows in the wake of Slavery. Slavery is an evil to the master. It is utterly subservient of the Christian religion. It violates the great law upon which that religion is based, and on account of which it vaunts its preemi- nence.

In 1845 Clay was run out of Kentucky by a mob. By then the Calhoun school had taken root and Southerners had begun arguing that slavery was not immoral, but a positive good:

Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually. In the meantime, the white or European race, has not degenerated. It has kept pace with its brethren in other sections of the Union where slavery does not exist. It is odious to make comparison; but I appeal to all sides whether the South is not equal in virtue, intelligence, patriotism, courage, disinterestedness, and all the high qualities which adorn our nature.

But I take higher ground. I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good--a positive good.

This is not just a rebuke of abolitionist thinking, but a rebuke of Jeffersonian thinking. Fifteen years later, Alexander Stephens would call Jefferson out by name arguing that his presumption of equality among men was a grievous error.

Perhaps this is too crude an interpretation but the graph above, measuring the incredible rise in the wealth represented by the pilfering of black labor, tracks directly with the political debate. When slaves were worth only a cool $300 million, property in man was an "unhappy influence." When that number skyrocketed in excess of $3 billion, suddenly it was a "positive good." Perhaps this is to deterministic. I leave it to my fellow commenters to color in the portrait. At any rate the notion that such an interest--by far the greatest collective asset in the country at the time--could be merely incidental to the war is creationist quackery.

But on to the problem.

Ron Paul's argument is essentially that it would have been better for the government to bail out slave-holders by effecting a mass purchase of blacks. This would have saved a lot of money, as well as the lives and limbs of a lot of white people. I do not believe that saving lives and limbs of any people--white or black--to be a disreputable goal. But I refuse to lose sight of the fact that slavery was, itself, war. And the lives and limbs of black people were perpetually at stake for centuries. From 1860 to 1865 the rest of the country received a concentrated dose of that medicine which black people had been made to quaff for over two and a half centuries. It is now a century and a half later, but still in some corners of white America it is fashionable to remain embittered.

Nevertheless, the saving of people is, indeed, a noble goal, and Paul is not without at least the rudiments of a case. Enslaved black people were constructed into an interest representing $3 billion. ($70-75 billion in 21st century money.) But including expenditures, loss of property, loss of life (human capital,) the war, according to Ransom, costs $6.6 billion.

The numbers are clear--the South's decision to raise an army, encourage sedition among its neighbors, and fire on federal property, was an economic disaster for white America. Moreover, the loss of 600,000 lives, in a war launched to erect an empire on the cornerstone of white supremacy and African slavery, was a great moral disaster for all corners of America.

In the most crude sense, it would have been much "cheaper" for the government to effect a mass purchase. But how? Ransom gives us some thoughts:

One "economic" solution to the slave problem would be for those who objected to slavery to "buy out" the economic interest of Southern slaveholders. Under such a scheme, the federal government would purchase slaves. A major problem here was that the costs of such a scheme would have been enormous. Claudia Goldin estimates that the cost of having the government buy all the slaves in the United States in 1860, would be about $2.7 billion (1973: 85, Table 1). Obviously, such a large sum could not be paid all at once. Yet even if the payments were spread over 25 years, the annual costs of such a scheme would involve a tripling of federal government outlays (Ransom and Sutch 1990: 39-42)! The costs could be reduced substantially if instead of freeing all the slaves at once, children were left in bondage until the age of 18 or 21 (Goldin 1973:85). Yet there would remain the problem of how even those reduced costs could be distributed among various groups in the population. The cost of any "compensated" emancipation scheme was so high that even those who wished to eliminate slavery were unwilling to pay for a "buyout" of those who owned slaves.

It is statement on the quality of our journalism, that I have seen Ron Paul repeatedly note that compensated emancipation would have avoided the Civil War, but I never seen a journalist ask him "How?" The "How" is quite clear--either by tripling the federal budget for 25 years, or through the (continued) enslavement of children.

These are all questions from the buyer-side. What about the seller? Would slaveholders willingly sell at "fair" price? How do we decide fair?

Edward Gaffney offers some thoughts in comments:

[A]s a slaveowner, you know that an abolitionist government values slaves more than you. In particular, they don't have a reason to pay lower prices as they buy more slaves. Therefore, the market in slaves breaks down immediately upon the beginning of compensated emancipation. Suddenly, there's a big buyer who will keep on buying. Just like a bond trader, why would you charge a big buyer the liquid market price if you know he's not going to stop buying? You should charge him the highest value of the last slave owned by any slaveowner, at the very least.

This is the theory of the cartel in the economics of industrial organisation. The social apparatus of a slaveholding society should minimise the number of defections from this cartel by easy sellers; in particular, they would fear that one's status would fall if one chooses money while one's neighbours choose to continue owning human beings. Sellers now have the market power; the price rises as a result.

A government which buys slaves, with the explicit intent to buy all slaves, is in a poor bargaining position versus slaveowners.. Signalling your intention to buy up all the supply of a commodity on the market increases the price you'll pay, whether that be bonds or human beings.

The thought-experiment, here, needs to be full gamed out. Ostensibly, in the government you have a buyer which, faced with the threat of mass violence, is willing to pay a large sum to end slavery. In slave-holders you have a seller, that does not want to sell, that has reacted violently to recent talk of selling, that, further, believes slavery is a good thing, ordained by God and the Bible. The greater country--having rejected war as an option--has no ability to compel this seller to any price. On the contrary, the country is, itself, partially dependent on slave-holders. ("By the mid 1830s, cotton shipments accounted for more than half the value of all exports from the United States," writes Ransom.)

How does one make this work? And more importantly, why do we need to?

We are united in our hatred of war and our abhorrence of violence. But a hatred of war is not enough, and when employed to conjure away history, it is a cynical vanity which posits that one is, somehow, in possession of a prophetic insight and supernatural morality which evaded our forefathers. It is all fine to speak of how history "should have been." It takes something more to ask why it wasn't, and then to confront what it actually was.

H/T to Yglesias for much of this post.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17153 followers