Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 16

May 16, 2014

Coming Soon: Why Reparations Make Sense

Deuteronomy 15: 12-15:

And if thy brother, an Hebrew man, or an Hebrew woman, be sold unto thee, and serve thee six years; then in the seventh year thou shalt let him go free from thee. And when thou sendest him out free from thee, thou shalt not let him go away empty: Thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith the LORD thy God hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him. And thou shalt remember that thou wast a bondman in the land of Egypt, and the LORD thy God redeemed thee: therefore I command thee this thing to day.

John Locke, Second Treatise of Civil Government:

Besides the crime which consists in violating the law, and varying from the right rule of reason, whereby a man so far becomes degenerate, and declares himself to quit the principles of human nature, and to be a noxious creature, there is commonly injury done to some person or other, and some other man receives damage by his transgression: in which case he who hath received any damage, has, besides the right of punishment common to him with other men, a particular right to seek reparation…

Bailey Wyatt, freedman:

We has a right to the land where we are located. For why? I tell you. Our wives, our children, our husbands, has been sold over and over again to purchase the lands we now locates upon; for that reason we have a divine right to the land…And then didn’t we clear the land, and raise the crops of corn, of cotton, of tobacco, of rice, of sugar, of everything. And then didn’t them large cities in the North grow up on the cotton and the sugars and the rice that we made? I say they has grown rich, and my people is poor.

The Atlantic, next week:

May 13, 2014

When School Reform And Democracy Meet

Three years ago Facebook CEO pledged $100 million to improve Newark's schools. In this week's New Yorker, Dale Russakoff offers an enlightening and depressing portrait of how that money was spent and what it achieved. The story is a welcome corrective to the bromide that "government should be run like a business"--as though business is some unassailable fortress of morality.

School reformers promised to clean up a bloated and corrupt school administration. But what emerges in its place is system in which various "consultants" are paid millions to deliver minimal results. And those results are meant to be delivered on a fast-food schedule:

On a Saturday morning later that month, Booker and Cerf met privately on the Rutgers-Newark campus with twenty civic leaders who had hoped that the Zuckerberg gift would unite the city in the goal of improving the schools. Now they had serious doubts. “It’s as if you guys are going out of your way to foment the most opposition possible,” Richard Cammarieri, a former school-board member who worked for a community-development organization, told them.

Booker acknowledged the missteps, but said that he had to move quickly. He and Christie could be out of office within three years. If a Democrat defeated Christie in 2013, he or she would have the backing of the teachers’ unions and might return the district to local control. “We want to do as much as possible right away,” Booker said. “Entrenched forces are very invested in resisting choices we’re making around a one-billion-dollar budget.” Participants in the meeting, who had worked for decades in Newark, were doubtful that reforms imposed over three years would be sustainable.

The "going out of your way to foment opposition" critique sounds really familiar. As does the anti-democratic streak which seems to haunt "reformers" and classical progressives of every age. One strategy Booker might have embraced was committing to making the case for school reform to Newark voters, and voters in New Jersey at large--be that as mayor or governor--over the long term. (Newark's schools are under the control of the state.) Instead Booker, chose another strategy--one that assumes an inability to convince the people whom Booker was charged with serving.

In any political fight worth having, one will likely tangle with "entrenched forces." The beauty of democracy is the right (and I'd say obligation) to convince a critical mass of voters, that those forces are acting counter to the public interest. And if you can't do that, then it's worth examining both your cause and your approach. This is especially true of parents who have a direct interest in the education of their children. If you begin from the premise that you can not convince parents, then I doubt the wisdom of your entire plan for their children.

I say that as someone who is unconvinced that teachers should be tenured. I say that as someone who thinks Booker makes a good point about seniority. I say that as someone who thinks making teaching a lucrative profession for those who excel at it is a good idea. I wish he'd spent more time trying to convince the people of Newark of this. If the interests really are as mighty as you claim, expecting to neutralize them in three years is not very serious.

May 12, 2014

The Inhumanity of the Death Penalty

Fifteen years ago, Clayton Lockett shot Stephanie Neiman twice, then watched as his friends buried her alive. Last week, Lockett was tortured to death by the state of Oklahoma. The torture was not so much the result of intention as neglect. The state knew that its chosen methods—a triple-drug cocktail—could result in a painful death. (An inmate executed earlier this year by the method was heard to say, "I feel my whole body burning.") Oklahoma couldn't care less. It executed Lockett anyway.

Over at Bloomberg View, Ramesh Ponnuru has taken the occasion to pen a column ostensibly arguing against the death penalty. But Ponnuru, evidently embarrassed to find himself in liberal company, spends most of the column dismissing the arguments of soft-headed bedfellows:

Indeed it would. But the reason we don't do this is contained within Ponnuru's inquiry: bias. When Ponnuru suggests that the way to correct for the death penalty's disproportionate use is to execute more white people, he is presenting a world in which the death penalty has neither history nor context. One merely flips the "Hey Guys, Let's Not Be Racist" switch and then the magic happens.On the core issue—yes or no on capital punishment—I'm with the opponents. Better to err on the side of not taking life. The teaching of the Catholic Church, to which I belong, seems right to me: The state has the legitimate authority to execute criminals, but it should refrain if it has other means of protecting people from them. Our government almost always does.

Still, when I hear about an especially gruesome crime, like the one the Oklahoma killer committed, I can't help rooting for the death penalty. And a lot of the arguments its opponents make are unconvincing.

Take the claims of racial bias—that we execute black killers, or the killers of white victims, at disproportionate rates. Even if those disputed claims are true, they don't point toward abolition of the death penalty. Executing more white killers, or killers of black victims, would reduce any disparity just as well.

Those of us who cite the disproportionate application of the death penalty as a reason for outlawing it do so because we believe that a criminal-justice system is not an abstraction but a real thing, existing in a real context, with a real history. In America, the history of the criminal justice—and the death penalty—is utterly inseparable from white supremacy. During the Civil War, black soldiers were significantly more likely to be court-martialed and executed than their white counterparts. This practice continued into World War II. "African-Americans comprised 10 percent of the armed forces but accounted for almost 80 percent of the soldiers executed during the war," writes law professor Elizabeth Lutes Hillman.

In American imagination, the lynching era is generally seen as separate from capital punishment. But virtually no one was ever charged for lynching. The country refused to outlaw it. And sitting U.S. senators such as Ben Tillman and Theodore Bilbo openly called for lynching for crimes as grave as rape and as dubious as voting. Well into the 20th century, capital punishment was, as John Locke would say, lynching "coloured with the name, pretences, or forms of law."

The youngest American ever subjected to the death penalty was George Junius Stinney. It is very hard to distinguish his case from an actual lynching. At age 14, Stinney, a black boy, walked to the execution chamber

with a Bible under his arm, which he later used as a booster seat in the electric chair. Standing 5 foot 2 inches (157 cm) tall and weighing just over 90 pounds (40 kg), his size (relative to the fully grown prisoners) presented difficulties in securing him to the frame holding the electrodes. Nor did the state's adult-sized face-mask fit him; as he was hit with the first 2,400 V surge of electricity, the mask covering his face slipped off, “revealing his wide-open, tearful eyes and saliva coming from his mouth ... After two more jolts of electricity, the boy was dead."

Living with racism in America means tolerating a level of violence inflicted on the black body that we would not upon the white body. This deviation is not a random fact, but the price of living in a society with a lengthy history of considering black people as a lesser strain of humanity. When you live in such a society, the prospect of incarcerating, disenfranchising, and ultimately executing white humans at the same rate as black humans makes makes very little sense. Disproportion is the point.

The "Hey Guys, Let's Not Be Racist" switch is really "Hey Guys, Let's Pretend We Aren't American" switch or a "Hey Guys, Let's Pretend We Aren't Human Beings" switch. The death penalty—like all state actions—exists within a context constructed by humans, not gods. Humans tend to have biases, and the systems we construct often reflect those biases. Understanding this, it is worth asking whether our legal system should be in the business of doling out an ultimate punishment, one for which there can never be any correction. Citing racism in our justice system isn't mere shaming, it's a call for a humility and self-awareness, which presently evades us.

I was sad to see Ponnuru's formulation, because it so echoed the unfortunate thoughts of William F. Buckley. In 1965, Buckley debated James Baldwin at the Cambridge Union Society. That was the year John Lewis was beaten at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and Viola Liuzzo was shot down just outside of Selma, Alabama. In that same campaign, Martin Luther King gave, arguably, his greatest speech. ("How Long? Not long. Truth forever on the scaffold. Wrong forever on the throne.") In whole swaths of the country, black people lacked the basic rights of citizenship—central among them, the right to vote. Buckley spent much of his time sneering at complaints of American racism. When the issue of the vote was raised Buckley responded by saying that the problem with Mississippi wasn't that "not enough Negroes have the vote but that too many white people are voting."

There's something revealed in the logic—in both Ponnuru and Buckley's case—that we should fix disproportion by making more white people into niggers. It is the same logic of voter-ID laws, which will surely disenfranchise huge swaths of white voters, for the goal of disenfranchising proportionally more black voters. I'm not sure what all that means—it's the shadow of something I haven't worked out.

May 8, 2014

Bill Clinton Was Racialized, Too

My colleague Peter Beinart rebukes Congressman Bennie Thompson's claim that Clarence Thomas is an "Uncle Tom." He then goes on to challenge the explanatory power of racism in understanding some of President Obama's more unhinged foes:

Conservatives may never have questioned Bill Clinton’s Christianity or his claim to being born in the United States. But they challenged his legitimacy just as aggressively as they’ve challenged Obama’s.

In May 1993, speaking before hundreds of servicemen at a military banquet, Major General Harold Campbell used the phrases “dope smoking, skirt chasing, draft dodging” to describe his commander-in-chief. The following May, Rush Limbaugh accused the Clintons of having ordered the murder of White House lawyer Vince Foster. That November, Senator Jesse Helms said, “Mr. Clinton better watch out if he comes down here [to North Carolina]. He'd better have a bodyguard.” On his television show, Jerry Falwell hawked videos purporting to prove that as governor of Arkansas, Clinton had overseen a massive drug-running scheme. Eighteen House Republicans introduced legislation to impeach Clinton in November 1997, months before America learned the name “Monica Lewinsky.”

It's certainly true that white politicians are not immune to campaigns of delegitimization. Obama has made the same point as Beinart. But I think this view deserves more scrutiny.

As Peter notes, the anti-Obama paranoia focuses on his citizenship—both broad and narrow. This is not just another means of delegitimization, but a specific specimen with racist roots. In the broadest sense, the idea that black people are not quite Americans, but an alien presence unworthy of citizenship, did not begin with Barack Obama. It's all very nice that Martin Luther King is now hailed as the quintessential American. In his day, he was regarded by forces, high in the American government, as an agent of foreign powers. Slaveholding moderates dreamed of shipping blacks back to their "native land" of Africa—despite the fact that Africans had arrived in the "New World" before most of the families of the slaveholders. In the mid-19th century, states like Illinois sought to expel the black alien presence.

For Obama, the delegitimizing does not even end with his citizenship, but with his very person. This attack has a history. The claim that Obama didn't actually write Dreams Of My Father, for instance, echoes earlier claims that lodged against another prominent biracial African-American:

About eight years ago I knew this recreant slave, Frederick Bailey, (instead of Douglass.) He then lived with Edward Covy, and was an unlearned, and rather an ordinary Negro, and I am confident he was not capable of writing the Narrative alluded to; for none but an educated man, and one who had some knowledge of the rules of grammar, could write so correctly.

African-Americans of some accomplishment have a deep acquaintance with this kind of white incredulity. Yesterday it was cries of unlearned, ordinary Negro. Today it is cries of Affirmative Action. (Even when you went to a black school.) Or it's Donald Trump demanding Barack Obama's college transcripts. The spectacle of a black man forced to present his papers to white people is not some new incomprehensible response to our first Hawaiian president. It is an old and predictable response to black achievement. It may well be true that Barack Obama and Bill Clinton have endured the same amount of disrespect. But the nature of that disrespect matters. It matters that Rush Limbaugh did not refer to healthcare in the Clinton era as reparations. All kinds of crazy are not equal, and in America, racist crazy has a special history worthy of highlighting.

Even Bill Clinton did not exist in a bubble of neutralized racism. He was a product of American politics in the post-Civil Rights era, and thus had to cope with all the requisite forces. Racism does not merely concern itself with individual enmity, but with group interests. The men who killed Andrew Goodman did not merely hate him individually, they hated what he represented. By the time Bill Clinton came to prominence, his party was closely associated with black interests. This was problem. And Clinton knew it.

"The day he told that fucking Jackson off," a white electrician told a pollster, "Is the day he got my vote."

It's worth considering this attack on Abraham Lincoln by Stephen Douglass during their famed debates:

I ask you, are you in favor of conferring upon the negro the rights and privileges of citizenship? ("No, no.") Do you desire to strike out of our State Constitution that clause which keeps slaves and free negroes out of the State, and allow the free negroes to flow in, ("never,") and cover your prairies with black settlements? Do you desire to turn this beautiful State into a free negro colony, ("no, no,") in order that when Missouri abolishes slavery she can send one hundred thousand emancipated slaves into Illinois, to become citizens and voters, on an equality with yourselves? ("Never," "no.")

If you desire negro citizenship, if you desire to allow them to come into the State and settle with the white man, if you desire them to vote on an equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible to office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights, then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro. ("Never, never.") For one, I am opposed to negro citizenship in any and every form. (Cheers.)

I believe this Government was made on the white basis. ("Good.") I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever, and I am in favor of confining citizenship to white men, men of European birth and descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes, Indians, and other inferior races. ("Good for you." "Douglas forever.")

Abraham Lincoln's light skin did not save him from a racist political attack, anymore than it saved him from a racist assassination plot. Indeed it is eery to see how much the words of Stephen Douglass ("I believe this government was made on the white basis") were echoed by John Wilkes Booth ("This country was formed for the white, not for the black man"). American politics cannot escape the winds of white supremacy.

White supremacy birthed American politics. In the 1990s, as today, the Democratic Party was perceived by many as the party of black interests. It's not incidental that many of Clinton's most crazed critics (Jesse Helms) and violent critics (the militia movement) were no strangers to white supremacy. That the Black Democratic Party is now actually headed by a black man is bound to cause some portion of America to feel a certain way.

Beinart concludes by arguing:

To believe that the right’s hostility to Obama stems mostly from his race is actually comforting, since it suggests that the next Democratic president won’t have it nearly as bad. If you believe that, Hillary Clinton has a bridge she’d like to sell you.

The hostility does not stem "from his race" but from racism. (And "mostly" is beside the point. Any amount of racism must be intolerable.) Racism—and sexism and homophobia—are about organizing power, not merely disliking the cut of one's jib. And if Hillary Clinton becomes president, she will have to cope with being perceived as a woman representing the interests of black people and women of all ethnicities. Sexism will never be off the stage. Nor will racism.

May 1, 2014

This Town Needs a Better Class of Racist

The question Cliven Bundy put to his audience last week—Was the black family better off as property?—is as immoral as it unoriginal. As both Adam Serwer and Jamelle Bouie point out, the roster of conservative theorists who imply that black people were better off being whipped, worked, and raped are legion. Their ranks include economists Walter Williams and Thomas Sowell, former congressman Allen West, sitting Representative Trent Franks, singer Ted Nugent, and presidential aspirants Rick Santorum and Michele Bachmann.

A fair-minded reader will note that each of these conservatives is careful to not praise slavery and to note his or her disgust at the practice. This is neither distinction nor difference. Cliven Bundy's disquisition begins with a similar hedge: "We've progressed quite a bit from that day until now and we sure don't want to go back." With so little substantive difference between Bundy and other conservatives, it becomes tough to understand last week's backpedaling in any intellectually coherent way.

But style is the hero. Cliven Bundy is old, white, and male. He likes to wave an American flag while spurning the American government and pals around with the militia movement. He does not so much use the word "Negro"—which would be bad enough—but "nigra," in the manner of villain from Mississippi Burning or A Time to Kill. In short, Cliven Bundy looks, and sounds, much like what white people take racism to be.

The problem with Cliven Bundy isn't that he is a racist but that he is an oafish racist. He invokes the crudest stereotypes, like cotton picking. This makes white people feel bad. The elegant racist knows how to injure non-white people while never summoning the specter of white guilt. Elegant racism requires plausible deniability, as when Reagan just happened to stumble into the Neshoba County fair and mention state's rights. Oafish racism leaves no escape hatch, as when Trent Lott praised Strom Thurmond's singularly segregationist candidacy.

Elegant racism is invisible, supple, and enduring. It disguises itself in the national vocabulary, avoids epithets and didacticism. Grace is the singular marker of elegant racism. One should never underestimate the touch needed to, say, injure the voting rights of black people without ever saying their names. Elegant racism lives at the border of white shame. Elegant racism was the poll tax. Elegant racism is voter-ID laws.

"The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race," John Roberts elegantly wrote. Liberals have yet to come up with a credible retort. That is because the theories of John Roberts are prettier than the theories of most liberals. But more, it is because liberals do not understand that America has never discriminated on the basis of race (which does not exist) but on the basis of racism (which most certainly does.)

Ideologies of hatred has never required a coherent definition of the hated. Islamophobes kill Sikhs as easily as they kill Muslims. Stalin needed no consistent definition of "Kulaks" to launch a war of Dekulakization. "I decide who is a Jew," Karl Lueger said. Slaveholders decided who was a nigger and who wasn't. The decision was arbitrary. The effects are not. Ahistorical liberals—like most Americans—still believe that race invented racism, when in fact the reverse is true. The hallmark of elegant racism is the acceptance of mainstream consensus, and exploitation of all its intellectual fault lines.

Here is a lovely illustration of elegant racism:

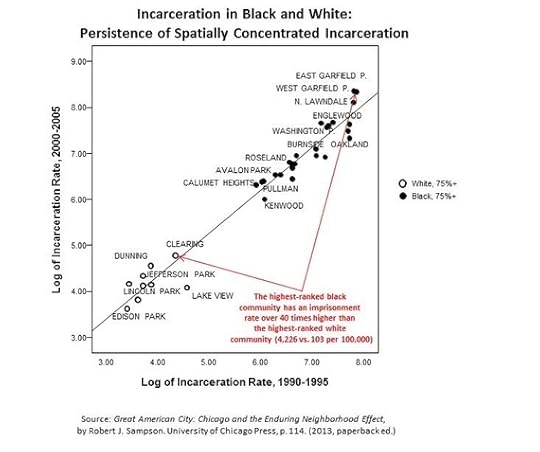

This graph is from Robert J. Sampson's essential 2011 profile of Chicago, Great American City. Sampson's data depicts incarceration rates in the early to mid-'90s in Chicago among black (black dots) and white neighborhoods (white dots.) Increasingly, sociologists like Sampson are showing us how our brute and strained vocabulary fails to articulate the problem of racism Conservatives and liberals frequently wonder how it could be that unequal outcomes endure for blacks and whites, even after controlling for income or "class." That is because conservatives and liberals underestimate the achievements of white supremacy and still believe that comparisons between a "black middle class" and a "white middle class" have actual meaning. In fact, black and white people—of any class—live in wholly different worlds.

A phrase like "mass incarceration" obviates the fact that "mass incarceration" is mostly localized in black neighborhoods. In Chicago during the '90s, there was no overlap between the incarceration rates of black and white neighborhoods. The most incarcerated white neighborhoods in Chicago are still better off than than the least incarcerated black neighborhoods. The most incarcerated black neighborhood in Chicago is 40 times worse than the most incarcerated white neighborhood.

Perhaps black people are for reasons of culture or genetics 40 times more criminal than white people. Or perhaps there is something more elegant at work:

The Justice Department announced today the largest monetary payment ever obtained by the department in the settlement of a case alleging housing discrimination in the rental of apartments. Los Angeles apartment owner Donald T. Sterling has agreed to pay $2.725 million to settle allegations that he discriminated against African-Americans, Hispanics and families with children at apartment buildings he controls in Los Angeles.

Throughout the 20th century—and perhaps even in the 21st—there was no more practiced advocate of housing segregation than the city of Chicago. Its mayors and aldermen razed neighborhoods and segregated public housing. Its businessmen lobbied for racial zoning. Its realtors block-busted whole neighborhoods, flipping them from black to white and then pocketing the profit. Its white citizens embraced racial covenants—in the '50s, no city had more covenants in place than Chicago.

If you sought to advantage one group of Americans and disadvantage another, you could scarcely choose a more graceful method than housing discrimination. Housing determines access to transportation, green spaces, decent schools, decent food, decent jobs, and decent services. Housing affects your chances of being robbed and shot as well as your chances of being stopped and frisked. And housing discrimination is as quiet as it is deadly. It can be pursued through violence and terrorism, but it doesn't need it. Housing discrimination is hard to detect, hard to prove, and hard to prosecute. Even today most people believe that Chicago is the work of organic sorting, as opposed segregationist social engineering. Housing segregation is the weapon that mortally injures, but does not bruise. The historic fumbling of such a formidable weapon could only ever be accomplished by a graceless halfwit—such as the present owner of the Los Angeles Clippers.

As Bomani Jones noted back in 2006, Donald Sterling has long been a practitioner of racism and the NBA could not have cared less. Jones is rightfully apoplectic at the present response. That is because he understands that the NBA, its players and its fans, don't so much object to Donald Sterling's racism—they object to his want of elegance.

Like Cliven Bundy, Donald Sterling confirms our comfortable view of racist. Donald Sterling is a "bad person." He's mean to women. He carouses with prostitutes. He uses the word "nigger." He fits our idea of what an actual racist must look like: snarling, villainous, immoral, ignorant, gauche. That the actual racism that Sterling long practiced, that this society has long practiced (and is still practicing) must attract significantly less note. That is because to see racism in all its elegance is to implicate not just its active practitioners, but to implicate ourselves.

How can it be that in a "black league," as Charles Barkley calls the NBA, an on-the-record structural racist like Donald Sterling was allowed to thrive? Everyone now wants to speak to Elgin Baylor. Where were all these people before? Where was Kevin Johnson? Where was the Los Angeles NAACP? When Donald Sterling was driving black tenants out of his buildings, where was David Stern?

Far better to implicate Donald Sterling and be done with the whole business. Far better to banish Cliven Bundy and table the uncomfortable reality of our political system. A racism that invites the bipartisan condemnation of Barack Obama and Mitch McConnell must necessarily be minor. A racism that invites the condemnation of Sean Hannity can't be much of a threat. But a racism, condemnable by all civilized people, must make itself manifest now and again so that we may celebrate how far we have come. Meanwhile racism, elegant, lovely, monstrous, carries on.

April 24, 2014

Cliven Bundy Wants to Tell You All About 'the Negro'

Let's be honest, 70% of teams in NBA could fold tomorrow + nobody would notice a difference w/ possible exception of increase in streetcrime

— Rep. Pat Garofalo (@PatGarofalo) March 9, 2014

A couple days ago Jonathan Chait asserted that modern conservatism is "doomed" because it is "rooted in white supremacy." The first claim may or may not be true, but there's little doubt about the second. Whether it's the Senate minority leader claiming that America should have remained legally segregated, a beloved cultural figure fondly recalling how happy black people were living under lynch law, a presidential candidate calling Barack Obama a "food-stamp president," or a campaign surrogate calling Barack Obama "

Cliven Bundy Wants To Tell You All About 'The Negro'

Let's be honest, 70% of teams in NBA could fold tomorrow + nobody would notice a difference w/ possible exception of increase in streetcrime

— Rep. Pat Garofalo (@PatGarofalo) March 9, 2014

A few days ago Jonathan Chait asserted that modern conservatism is "doomed" because it is "rooted in white supremacy." The first claim may or may not be true, but there's little doubt about the second. Whether it's the Senate minority leader claiming that America should have remained legally segregated, a beloved cultural figure fondly recalling how happy black people were living under lynch law, a presidential candidate calling Barack Obama a "food-stamp president" or a campaign surrogate calling Barack Obama "

April 22, 2014

Cliven Bundy and the Tyranny All Around Us

I've been laughing my way through the Cliven Bundy fiasco because, as Jamelle Bouie suggests, there may be no better example of racist privilege than the right to flout the government's authority and then back its agents down at gunpoint. Bouie asks, hypothetically, how we'd respond if Bundy were black.

Inasmuch as this is even a question, American history has already answered it (emphasis added):

In an 18-month investigation, The Associated Press documented a pattern in which black Americans were cheated out of their land or driven from it through intimidation, violence and even murder.

In some cases, government officials approved the land takings; in others, they took part in them. The earliest occurred before the Civil War; others are being litigated today. Some of the land taken from black families has become a country club in Virginia, oil fields in Mississippi, a major-league baseball spring training facility in Florida ...

The AP—in an investigation that included interviews with more than 1,000 people and the examination of tens of thousands of public records in county courthouses and state and federal archives—documented 107 land takings in 13 Southern and border states.

In those cases alone, 406 black landowners lost more than 24,000 acres of farm and timber land plus 85 smaller properties, including stores and city lots. Today, virtually all of this property, valued at tens of millions of dollars, is owned by whites or by corporations.

That is from the AP's exceptional (and oft-overlooked) 2001 series "Torn From The Land." What generally followed this tearing was not a patriotic defense of the little guy but mob violence and ethnic cleansing. In 1912, Forsyth County, Georgia, expelled 1,000 black people—10 percent of its total population—and appropriated their land. (For more on the subject, I suggest Marco Williams's superb documentary Banished.) The unfortunate fact is that plunder—of land, labor, children, whatever—is a defining characteristic of this country's relationship with black people. American militias have rarely formed to end that sort of plunder. They've generally formed to enable it.

The thing to do here, as Chris Hayes points out, is not to argue that Bundy should be subject to the kind of violence that black people who find themselves in dispute with the government's agents often are. (There's nothing for liberals to cheer about in a running gunfight over grazing fees.) The thing to do is to recognize the limits of our sympathies and try to extend them. "How about widening the aperture," Hayes asks, "for the tyranny you see all around you?"

April 18, 2014

Segregation Forever

A few weeks ago I wrote skeptically of the jaunty uplifting narrative that sees white supremacy's inevitable defeat. One reason I was so skeptical was because I'd been reading the reporting of Nikole Hannah-Jones. If you haven't read her coverage on housing segregation you should. And then you should read her piece from this month's magazine on the return of segregation in America's schools:

Schools in the South, once the most segregated in the country, had by the 1970s become the most integrated, typically as a result of federal court orders. But since 2000, judges have released hundreds of school districts, from Mississippi to Virginia, from court-enforced integration, and many of these districts have followed the same path as Tuscaloosa’s—back toward segregation. Black children across the South now attend majority-black schools at levels not seen in four decades. Nationally, the achievement gap between black and white students, which greatly narrowed during the era in which schools grew more integrated, widened as they became less so.

In recent years, a new term, apartheid schools—meaning schools whose white population is 1 percent or less, schools like Central—has entered the scholarly lexicon. While most of these schools are in the Northeast and Midwest, some 12 percent of black students in the South now attend such schools—a figure likely to rise as court oversight continues to wane. In 1972, due to strong federal enforcement, only about 25 percent of black students in the South attended schools in which at least nine out of 10 students were racial minorities. In districts released from desegregation orders between 1990 and 2011, 53 percent of black students now attend such schools, according to an analysis by ProPublica.

Hannah-Jones profiles the schools in Tuscaloosa where business leaders are alarmed to see their school system becoming more and more black, as white parents choose to send their kids to private (nearly) all-white academies or heavily-white schools outside the city. It's worth noting that the school at the center of Hannah-Jones' reporting--Central High School--was not a bad a school. On the contrary it was renowned for its football team as well its debate team.

But this did very little to slow the flight of white parents out of the district. (This is beyond the scope of Nikole's story, but I'd be very interested to hear more about the history of housing policy in the town.) Faced with the prospect of losing all, or most of their white families, Tuscaloosa effectively resegregated its schools.

There doesn't seem to be much of a political solution here. It's fairly clear that integration simply isn't much of a priority to white people, and sometimes not even to black people. And Tuscaloosa is not alone. I suspect if you polled most white people in these towns they would honestly say that racism is awful, and many (if not most) would be sincere. At the same time they would generally be lukewarm to the idea of having to "do something" in order to end white supremacy.

Ending white supremacy isn't really in the American vocabulary. That is because ending white supremacy does not merely require a passive sense that racism is awful, but an active commitment to undoing its generational effects. Ending white supremacy requires the ability to do math--350 years of murderous plunder are not undone by 50 years of uneasy cease-fire.

An latent commitment to anti-racism just isn't enough. But that's what we have right now. With that in mind, there is no reason to believe that a total vanquishing of white supremacy is necessarily in the American future.

"History," said President Barack Obama recently. "Travels not only forwards, history can travel backwards...Our rights, our freedoms -- they are not given. They must be won. They must be nurtured through struggle and discipline and persistence and faith."

Indeed. But for right now, the struggle for integration is largely over.

April 16, 2014

John Roberts and the Color of Money

My friend and MIT colleague Tom Levenson watched, with some interest, the debate between myself and Jonathan Chait. On a whim, Tom pulled together some more thoughts on campaign-finance reform that, I think, help spin this conversation forward. His insights are below.

There has been plenty of talk about the Ta-Nehisi Coates-Jonathan Chait argument over the term "black culture" in the context of the ills of poverty and the question of progress as seen through the lens of the actual history of America.

A drastically shortened version of Coates’s analysis is that white supremacy—and the imposition of white power on African-American bodies and property—have been utterly interwoven through the history of American democracy, wealth and power from the beginnings of European settlement in North America. The role of the exploitation of African-American lives in the construction of American society and polity did not end in 1865. Rather, through the levers of law, lawless violence, and violence under the color of law, black American aspirations to wealth, access to capital, access to political power, a share in the advances of the social safety net and more have all been denied with greater or less efficiency. There has been change—as Coates noted in a conversation he and I had a couple of years ago, in 1860 white Americans could sell children away from their parents, and in 1865 they could not—and that is a real shift. But such beginnings did not mean that justice was being done nor equity experienced.

Once you start seeing American history through the corrective lens created by the generations of scholars and researchers on whose work Coates reports, then it becomes possible—necessary, really—to read current events in a new light. Take, for example, the McCutcheon decision that continued the Roberts Court program of gutting campaign-finance laws.

The conventional—and correct, as far as it goes—view of the outcome, enabling wealthy donors to contribute to as many candidates as they choose, is that this further tilts the political playing field towards the richest among us at the expense of every American voter. See noted analyst Jon Stewart for a succinct presentation of this view.

But that first-order take on this latest from the Supreme Court's right wing misses a crucial dimension. It isn't just rich folks who benefit from the Roberts Court's view that money equals speech. Those who gain possess other key identifiers. For one thing, they form a truly a tiny elite. As oral arguments in McCutcheon v. FEC were being prepared last fall, the Public Campaign delivered a report on all those who approached the money limits the court struck down. They amount to just 1,219 people in the U.S.—that's four in every 1,000,000 of our population.

Unsurprisingly, most of the report simply reinforces the main theme of the reaction to the Supreme Court's decision: This is one more step toward securing governance of, for, and by rich people and their well-compensated servants. One of the most troubling aspects of the story is that the top donors in this country simply don't encounter ordinary folks, the middle class no more than the poor:

Nearly half of the elite donors (47.6 percent) live in the richest one percent of neighborhoods, as measured by per capita income, and more than four out of every five (80.5 percent) are from the richest 10 percent.

Equally unsurprisingly, the world of top donors is overwhelmingly male:

Of donors for whom gender data were available, only 25.7 percent of the elite donors in 2012 were women, even lower than the paltry one-third of donors giving at least $200 to a federal campaign that election cycle. Also, 304 superlimit donors have a spouse or other family member as another member of list, which could indicate either a very politically interested family or a way for one donor to circumvent the existing limits through contributions in his or her spouse’s name. Of the donors without another family member on the list, only 17.7 percent are women.

And against the argument that regardless of the source of the money, cash is gender blind, I give you both data and Nancy Pelosi:

House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) identifies big money as a key factor holding this number down: “If you reduce the role of money in politics and increase the level of civility, you’ll have more women elected to public office, and sooner, and that nothing is more wholesome to the governmental and political process than increased participation of women.”

In contrast, further increasing the role of money in politics by removing the aggregate contribution limit means the Supreme Court may end up pushing down women’s role in campaigns even further. CRP’s “Sex, Money and Politics,” report also found that “Women tend to make up a larger percentage of the donor pool when contribution amounts are limited by law.” It continues to note that the three cycles in which loopholes for sending unlimited contributions to political parties or outside groups like super PACs were largely closed, women played a larger role: “In the 2004, 2006 and 2008 cycles, which were the only three since 1990 with strict donation limits restricting the amount of money a single individual could give, the percentage of women as a portion of the donor pool increased.”

But even these pathologies are vastly less severe than those to be found through the lens of race. People of color are almost entirely absent from the top donor profile, and none more so than members of the community that white Americans enslaved for two centuries:

While more than one-in-six Americans live in a neighborhood that is majority African-American or Hispanic, less than one-in-50 superlimit donors do. More than 90 percent of these elite donors live in neighborhoods with a greater concentration of non- Hispanic white residents than average. African-Americans are especially underrepresented. The median elite donor lives in a neighborhood where the African-American population counts for only 1.4 percent, nine times less than the national rate.

In other words: Political money and hence influence at the top levels is disproportionately white, male, and with almost no social context that includes significant numbers of African Americans and other people of color.

This is why money isn't speech. Freedom of speech as a functional element in democratic life assumes that such freedom can be meaningfully deployed. But the unleashing of yet more money into politics allows a very limited class of people to drown out the money "speech" of everyone else—but especially those with a deep, overwhelmingly well documented history of being denied voice and presence in American political life.

Now take the work of the Roberts Court in ensuring that rule of cash, the engine of political power for an overwhelmingly white upper-upper crust, with combine those decisions with the conclusions of the court on voting rights, and you get a clear view of what the five-justice right-wing majority has done. Controlling access to the ballot has been a classic tool of white supremacy since the end of Reconstruction. It is so once again, as states seizing on the Roberts Court's Voting Rights Act decision take aim at exactly those tools with which African Americans increased turnout and the proportion of minority voters within the electorate. There's not even much of an attempt to disguise what's going on.

Add all this to the Roberts decision to free states from the tyranny of being forced to accept federal funds to provide healthcare to the poor. When John Roberts declared that Obamacare's Medicaid expansion would be optional, the decision sounded colorblind—states could deny succor to their poor of any race—in practice, that is to say in the real world, this decision hits individual African Americans and their communities the hardest . as Coates wrote way back when.

So: Money, which disproportionately defends existing power structures, is unfettered; ease of voting, which at least in theory permits challenges to such structures, is constrained; and a series of decisions seeming devoid of racial connection presses thumbs the scale ever harder against the chance that in the real-world African Americans will have get to play on a level field.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17142 followers