Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 15

June 12, 2014

Martin Luther King Makes the Case for Reparations

June 4, 2014

The Radical Practicality of Reparations

President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The Act granted reparations to Japanese-Americans interned during World War II. (Ronald Reagan Presidential Library And Museum)

President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The Act granted reparations to Japanese-Americans interned during World War II. (Ronald Reagan Presidential Library And Museum)David Frum has posted a rebuttal to my argument in favor of reparations. I appreciate David's engagement with the issue. I often miss the old days when The Atlantic's writers would engage each other in running debate, so I'm happy for the chance to get back into that kind of conversation here.

On y va.

David grounds his rebuttal in The Philadelphia Plan, an affirmative action program that David believes qualifies as reparations. I disagree. The Philadelphia Plan was an attempt to end job discrimination among firms doing business with the federal government. Originally it was isolated to the building trades in Philadelphia. This was not a mistake. "The NAACP wanted a tougher require; the unions hated the whole thing," said White House aide John Ehrlichman. "Before long, the AFL-CIO and the NAACP were locked in combat over one of the passionate issues of the day and the Nixon administration was located in the sweet and reasonable middle."

The Plan's proprietors showed little stomach for any kind of historical reckoning. President Richard Nixon's Assistant Secretary of Labor Arthur Fletcher, who helped create the Plan, targeted not just blacks, but "Orientals, American Indians and persons with Spanish surnames."

More importantly, The Philadelphia Plan was focused on ending present racist discrimination, not compensating for the past. In Philadelphia, a city that was 30 percent black, there were 12 minority unionized ironworkers and three black pipe-fitters. There was no black unionized work among the sheet metal trades, elevator constructors, or the stone-masons. From the perspective of reparations, one might calculate how much this discrimination had cost Philadelphia's black community and then attempt to compensate them. The Philadelphia Plan did not do this. Indeed Fletcher went so far as to declare himself neither interested in compensation nor "a fruitless debate about slavery and its debilitating legacy." The Philadelphia Plan was no more reparations than school busing was reparations.

The White House's appetite for these "reparations" proved short lived. In 1970, Nixon took The Philadelphia Plan national, expanding beyond the trades. In 1972, he ran against his own plan. Fletcher was forced out. The Democrats were tarred as the "quota party." "The zip went out of that integration effort," said then aide William Safire, "after the hard hats marched in support of Nixon on the war." So much for "reparations."

And so much for history. David goes on to assert that reparations for one group must necessarily lead to reparations for all groups:

With any program of reparations, likewise, other claimants will come forward. If African Americans are due payment for slavery and subjugation, what about Native Americans, who lost a whole continent? What about Mexican-Americans, who were deprived by the Mexican-American war of the right to migrate into half their former country? Japanese Americans, interned during World War II? Chinese Americans, the victims of coolie labor and the Oriental Exclusion Acts? Members of these groups may concede that they were not maltreated in the same way as African Americans—and may not be entitled to exactly the same consideration. But if black Americans are entitled to almost a trillion dollars in compensation (Coates suggests a figure of $34 billion a year “for a decade or two”) surely these other maltreated groups must be entitled at least to something?

This argument carries the virus of its own destruction. In fact reparations paid to Japanese-Americans for internment has been American policy for over 20 years. No reparations for African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, or Chinese-Americans followed. Even German-Americans and Italian-Americans who were also interned received no reparations.

The Japanese-American struggle for reparations is significant and important, not just for our present discussion, but because it serves as useful corrective for hagiographers of war. And it is not an obscure episode. Indeed, Japanese-American reparations were in the news this week, with the death of activist Yuri Kochiyama, one of the principal advocates of the cause. David treats Japanese-American reparations as an open question or a thought experiment. But it isn't. It's American history—and people charged with analyzing America should know it.

People who take up reparations arguments should especially know it because it presents us with some provocative questions. The collective ills of housing segregation—block-busting, redlining, segregated public-housing, the G.I. Bill, terrorism—continued long after Japanese-American internment. A serious interlocutor of reparations can not casually muster a melange of historical wrongs, but must directly explain why the Japanese-American case is compelling, but the more recent African-American case is not.

Slippery slopes will not do. The "If we give them one, they'll all have one" argument is demonstrably false. This is as it should be. The argument for black reparations is not simply "Hey guys, we did it for the Japanese-Americans so it must be right." A claim must stand on its arguments. Nothing would please me more than to read a 15,000 word "Case for Native American Reparations." I say this because we can't evaluate particular claims without understanding particular history. David, like many who believe reparations to be "impossible," is anxious to skip the history and leap to implementation. But the questions, themselves, prove that we are not prepared.

"Does a mixed-raced person qualify?" David asks. Probably so, given that there are very few "pure raced" black people who were injured by racism. Indeed, the lack of "purity" is parcel to the injury. Perhaps David wants to ask "Do black people with direct 'white' ancestry qualify?" The correct reply to this is "Were black people with direct 'white' ancestry victims of racist housing policy?" The answer to that question is knowable. But it is not the question we ask. Instead we focus on the myth of "race," while ignoring the demonstrable fact of injury.

This species of ignorance—of looking away—is old. In 1884, Harvard scientist Nathaniel Shaler assessed "The Negro Problem" in the pages of this very magazine. Shaler concluded that:

It was their presence here that was the evil, and for this none of the men of our century are responsible ... The burden lies on the souls of our dull, greedy ancestors of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, who were too stupid to see or too careless to consider anything but immediate gain ...

There can be no sort of doubt, that, judged by the light of all experience, these people are a danger to America greater and more insuperable than any of those that menace the other great civilized states of the world. The armies of the Old World, the inheritance of medievalism in its governments, the chance evils of Ireland and Sicily, are all light burdens when compared with this load of African negro blood that an evil past has imposed upon us.

At the very moment that Shaler was disowning American responsibility for enslavement, there were thousands, perhaps millions, of freedmen alive as well as their enslavers. It had barely been 20 years since enslavement was abolished. It had not been ten years since the rout of Reconstruction. In that time, sensible claims for reparations were being made. The black activist Callie House argued that pensions should be paid to freedmen and freedwomen for unpaid toil. The movement garnered Congressional support. But it failed, largely because, the country believed as Shaler did, that "none of the men of this century" were "responsible."

A similar moment finds us now. Even if one feels that slavery was too far into the deep past (and I do not, because I view this as a continuum) the immediate past is with us. Identifying the victims of racist housing policy in this country is not hard. Again, we have the maps. We have the census. We could set up a claims system for black veterans who were frustrated in their attempt to use the G.I. Bill. We could then decide what remedy we might offer these people and their communities. And there is nothing "impractical" about this.

The problem of reparations has never been practicality. It has always been the awesome ghosts of history. A fear of ghosts has sometimes occupied the pages of the magazine for which David and I now write. In other times banishment has been our priority. The mature citizen, the hard student, is now called to choose between finding a reason to confront the past, or finding more reasons to hide from it. David thinks HR-40 commits us to a solution. He is correct. The solution is to study. I submit his own article as proof of why such study is so deeply needed.

* The following books were essential to this piece:

Terry Anderson's The Pursuit of Fairness is a thorough review of the history affirmative action, a policy that many people talk about but fail to understand. Quotes of Fletcher and Ehrlichman are taken from Anderson's book. Mary Francis Berry's My Face Is Black Is True , is a chronicle of one of the earliest efforts, post-enslavement, for reparations led by the remarkable Callie House. Khalil Gibran Muhammad's The Condemnation of Blackness , is a useful corrective to the deceptive invocations of "black on black crime." Muhammad demonstrates that much of rhetoric around "black crime" is old and has its roots in our racist past.

The Radical Practicality Of Reparations

President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The Act granted reparations to Japanese-Americans interned during World War II. (Ronald Reagan Presidential Library And Museum)

President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The Act granted reparations to Japanese-Americans interned during World War II. (Ronald Reagan Presidential Library And Museum)David Frum has posted a rebuttal to my argument in favor of reparations. I appreciate David's engagement with the issue. I very much miss the old days of the "Voices" when The Atlantic's writers would engage each other in running debate. If this is not quite a return to such a time, I am still happy to take what I can get.

On y va.

David grounds his rebuttal in The Philadelphia Plan, an affirmative action program which David believes qualifies as reparations. I disagree. The Philadelphia Plan was an attempt to end job discrimination among firms doing business with the federal government. Originally it was isolated to the building trades in Philadelphia. The Plan's proprietors showed little stomach for any kind of historical reckoning. President Richard Nixon's Assistant Secretary of Labor Arthur Fletcher, who helped create the Plan, targeted not just blacks, but "Orientals, American Indians and persons with Spanish surnames."

More importantly, The Philadelphia Plan was focused on ending present racist discrimination, not compensating for the past. In Philadelphia, a city that was 30 percent black, there were 12 minority unionized ironworkers and three black pipe-fitters. There was no black unionized work among the sheet metal trades, elevator constructors or the stone-masons. From the perspective of reparations, one might calculate how much this discrimination had cost Philadelphia's black community and then attempt to compensate them. The Philadelphia Plan did not do this. Indeed Fletcher went so far as to declare himself neither interested in compensation nor "a fruitless debate about slavery and its debilitating legacy." The Philadelphia Plan was no more reparations, than school busing was reparations.

The White House's appetite for these "reparations" proved short lived. In 1970, Nixon took The Philadelphia Plan national. In 1972, he ran against it. Fletchers was forced out. The Democrats were tarred as the "quota party." "The zip went out of that integration effort," said then aide William Safire, "After the hard hats marched in support of Nixon on the war." So much for "reparations."

And so much for history. David goes on to assert that reparations for one group must necessarily lead to reparations for all groups:

With any program of reparations, likewise, other claimants will come forward. If African Americans are due payment for slavery and subjugation, what about Native Americans, who lost a whole continent? What about Mexican-Americans, who were deprived by the Mexican-American war of the right to migrate into half their former country? Japanese Americans, interned during World War II? Chinese Americans, the victims of coolie labor and the Oriental Exclusion Acts? Members of these groups may concede that they were not maltreated in the same way as African Americans—and may not be entitled to exactly the same consideration. But if black Americans are entitled to almost a trillion dollars in compensation (Coates suggests a figure of $34 billion a year “for a decade or two”) surely these other maltreated groups must be entitled at least to something?

This argument carries the virus of its own destruction. In fact reparations were paid to Japanese-Americans for internment has been American policy for over twenty years. No reparations for African-Americans, Mexican-Americans or Chinese-Americans followed. Even German-Americans and Italian-Americans who were also interned received no reparations.

The Japanese-American struggle for reparations is significant and important, not just for our present discussion, but because it serves as useful corrective for hagiographers of war. And it is not an obscure episode. Indeed, Japanese-American reparations were in the news this week, with the death of activist Yuri Kochiyama, one of the principal advocates of the cause. David treats Japanese-American reparations as an open question or a thought experiment. But it isn't. It's just American history--and people charged with analyzing America should know it.

People who take up reparations arguments should especially know it because it presents us with some provocative questions. The collective ills of housing segregation--block-busting, redlining, segregated public-housing, the G.I. Bill, terrorism--continued long after Japanese-American internment. A serious interlocutor of reparations can not thoughtlessly muster a melange of historical wrongs, but must directly explain why the Japanese-American case is compelling, but the more recent African-American case is not.

Slippery slopes will not do. The "If we give them one, they'll all have one" argument is demonstrably false. This is as it should be. The argument for black reparations is not simply "Hey guys, we did it for the Japanese-Americans so it must be right." A claim must stand on its arguments. Nothing would please me more than to read a 15,000 word "Case for Native American Reparations." I say this because we can't evaluate particular claims without understanding particular history. David, like many who believe reparations to be "impossible," is anxious to skip the history, and leap to implementation. But the questions, themselves, prove that we are not prepared.

"Does a mixed-raced person qualify?" David asks. Probably so, given that there are very few "pure raced" black people who were injured by racism. Indeed, the lack of "purity" is parcel to the injury. Perhaps David wants to ask "Do black people with direct 'white' ancestry qualify?" The correct reply to this is "Were black people with direct 'white' ancestry victims of racist housing policy?" That question is knowable. But it is not the question we ask. Instead we focus on the myth of "race," while ignoring the demonstrable fact of injury.

This species of ignorance--of looking away--is old. In 1884, Harvard scientist Nathaniel Shaler assessed "The Negro Problem" in the pages of this very magazine. Shaler concluded that:

It was their presence here that was the evil, and for this none of the men of our century are responsible...The burden lies on the souls of our dull, greedy ancestors of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, who were too stupid to see or too careless to consider anything but immediate gain...

There can be no sort of doubt, that, judged by the light of all experience, these people are a danger to America greater and more insuperable than any of those that menace the other great civilized states of the world. The armies of the Old World, the inheritance of medievalism in its governments, the chance evils of Ireland and Sicily, are all light burdens when compared with this load of African negro blood that an evil past has imposed upon us.

At the very moment that Shaler was disowning American responsibility for enslavement, there were thousands, perhaps millions, of freedman alive as well as their enslavers. It had barely been twenty years since enslavement was abolished. It had not been ten years since the rout of Reconstruction. In that time, sensible claims for reparations were being made. The black activist Callie House argued that pensions should be paid to freedmen and freedwomen for unpaid toil. The movement garnered Congressional support. But it failed, largely because, the country believed as Shaler did, that "none of the men of this century" were "responsible."

A similar moment finds us now. Even if one feels that slavery was too far into the deep past (and I do not, because I view this as a continuum) the immediate past is with us. Identifying the victims of racist housing policy in this country is not hard. Again, we have the maps. We have census. We could set up a claims system for black veterans who were frustrated in their attempt to use the G.I. Bill. We could then decide what remedy we might offer these people and their communities. And there is nothing "impractical" about this.

The problem of reparations has never been practicality. It has always been the awesome ghosts of history. A fear of ghosts has sometimes occupied the pages of the magazine for which David and I now writes. In other times banishment has been our priority. The mature citizen, the hard student, is now called to choose between finding a reason to confront the past, or finding more reasons to hide from it. David thinks HR-40 commits us to a solution. He is correct. The solution is to study. I submit his own article as proof of why such study is so deeply needed.

*The following books were essential to this piece:

Terry Anderson's The Pursuit of Fairness is a thorough review of the history Affirmative Action, a policy which many people talk about, but fail to understand. Mary Francis Berry's My Face Is Black Is True , is a chronicle of one of the earliest efforts, post-enslavement, for reparations led by the remarkable Callie House. Khalil Gibran Muhammad's The Condemnation of Blackness , is a useful corrective to the deceptive invocations of "black on black crime." Muhammad demonstrates that much of rhetoric around "black crime" is old and has its roots in our racist past.

June 2, 2014

The Case for American History

I wanted to take moment to reply to Kevin Williamson's Case Against Reparations. I wanted to do that, primarily, because his piece covers many of the objections, but also because I've always been an admirer of Williamson's writing, if not his ideas. Among those ideas is a kind of historical creationism which holds that "race" is a fixed thing. The problems with this approach are many, and duly apparent from the outset.

Williamson says he is opposed to "converting the liberal Anglo-American tradition of justice into a system of racial apportionment." He then observes that, in fact, that tradition, itself, has always been deeply concerned with "racial apportionment." Thus within the second paragraph, Williamson is undermining his own thesis—if the Anglo-American tradition is what he concedes it to be, no "converting" is required. We reverse polarity for a time, and then we all live happily ever after.

Probably not. That is because Williamson's entire framing is wrong. Reparations are not due because black people are black, but because black people have been injured. And the Anglo-American tradition has never been a system of "racial apportionment," but of racist apportionment. Like most writers and public intellectuals (liberal and conservative) Williamson reply is rooted in the idea of "race" as constant—i.e. there is a "black race" which can be traced back to Africa, and a "white race" that can be traced back to Europe. There certainly is such a thing as African and European ancestry, and that ancestry is not entirely irrelevant to our world. But ancestry is tangential, and sometimes wholly unrelated, to racism, injury, and reparations.

We know this because there is no constant idea of "black" or "white" across time or space. We know this because Charlie Patton fathered the blues, and Alessandro de Medici ruled in Venice. Black in America is not black in Brazil, and black in modern America is not even black in 17th century Louisiana. Nor are people we consider "white" today any sort of constant. Throughout American history it has been common to speak of an "Italian race," an "Irish race," a "Frankish race," a "Jewish race" even "Southern race." One might take a hard look at Williamson's agreeable portrait, for instance, and note the problem of assigning anyone to a race. "Race," writes the imminent historian Nell Irvin Painter, "is an idea, not a fact."

In this country, at this moment, "African-Americans" are an ethnic group comprised of individuals of varying degrees of direct African ancestry. Nothing about this fact necessitated plunder or injury, and it is the injury—through red-lining, black codes, slaves codes, lynching, ghettoization, fraud, rape, and murder—with which reparations concerns itself. The point is not "racial apportionment," which is to say giving people things because are black. It is injury apportionment, which is to say restoring things to people who have been plundered.

Racism, and its progeny white supremacy, is concerned with dividing human beings, on the basis of ancestry (which is very real) and slotting them into a hierarchy (which is in invention.) "Race" is that hierarchy—and any study of the word across history bears out its relationship to assigning value and scale across humanity. In polite society we've moved past overtly hierarchal ideas about "race," but the problem of imprecise naming remains with us. Let us bypass that imprecision—the Anglo-American tradition which Williamson extolls has, as he concedes, sought to erect and uphold a racist hierarchy. Reparations seeks its total and complete destruction.Williamson believes that reparations must either boil down to a "symbolic political process" or series of polices that helps America's poor and disproportionately aids African-Americans. How, Williamson's asks, can one make a claim on behalf of Sasha and Malia Obama, in a world of poor whites? In much the same way that a factory which pumps toxins into a poor neighborhood is not indemnified because a plaintiff rises to become a millionaire. Taking Williamson's argument to its logical conclusion, a businessman brutalized by the police should never sue the city because, well, homelessness.

People who are injured sometimes achieve great things—this does not obviate the fact of their injury, nor their claim to recompense. Warren Moon achieved more than the vast majority of white quarterbacks. Had racism not forced him into the CFL for the first five crucial years of his career, he might have had more success than any quarterback to ever play the game. Satchel Paige enjoys an honor which the vast majority of white baseball players shall never glimpse—induction in the Hall of Fame. What might Paige achieved had he not been injured by white supremacy for the vast majority of his career? Mr. Clyde Ross is a homeowner, and considerably better off than many of his North Lawndale neighbors. To achieve this he worked three jobs and lost time that he should have been able to invest in his children. What might Mr. Ross have been had he not endured racist plunder from Clarksdale to Chicago?

The problem of racism is not synonymous with the problem of the poverty line. Indeed, it is often in the fate of the most conventionally successful African-Americans that we see the corrupt social contract foisted upon them. The injury of racism means many things, virtually all of them bad. It means making $100,000 a year but living in neighborhoods equivalent to white people who make $30,000 a year. It means belonging to a class whose men comprise some eight percent of the world's entire prison population. It means if you do go to college still enjoying lesser employment prospects than white college graduates. It means living in a family with roughly a 20th of the wealth of those who do not suffer your particular ailment. In short, it means quite a bit—and these effects do not merely haunt the poor. My heart bleeds for the white child injured by the departure of parents. But God forbid the injury of racism be added to the burden.

The pervasive effects of the injury should not surprise—the injuring and exploitation of black people regardless of economic class has been one of the dominant themes of American history. It is only the obviation, or ignorance, of history that allows us to escape this. The result must be an especially tortured specimen of reasoning:

Some blacks are born into college-educated, well-off households, and some whites are born to heroin-addicted single mothers, and even the totality of racial crimes throughout American history does not mean that one of these things matters and one does not. Once that fact is acknowledged, then the case for reparations is only moral primitivism.

Williamson's "fact" can not be acknowledged because, even by Williamson's crude measures, it is artifice. There are—at most—1.5 million people who use heroin in this country. The ranks of the African-American poor are roughly eight times that. More importantly, the claim of reparations does not hinge on every individual white person everywhere being wealthy. That is because reparations is not a claim against white Americans, anymore than reparations paid to interned Japanese-Americans was a claim against non-Japanese-Americans. The claim was brought before the multi-ethnic United States of America.

There seems to be great confusion on this point. The governments of the United States of America—local, state and federal—are deeply implicated in enslavement, Jim Crow, redlining, New Deal racism, terrorism, ghettoization, housing segregation. The fact that one's ancestors were not slave-traders or that one arrived here in 1980 is irrelevant. I did not live in New York when the city railroaded the Central Park Five. But my tax dollars will pay for the settlement. That is because a state is more than the natural lives, or occupancy, of its citizens. People who object to reparations for African-Americans because they, individually, did nothing should also object to reparations to Japanese-Americans, but they should not stop there. They should object to the Fourth of July, since they, individually, did nothing to aid the American Revolution. They should object to the payment of pensions for the Spanish-American war, since they did not fight. Indeed they should object to government and society itself, because its existence depends on outliving its individual citizens.

A sovereignity which dies with every generation is a failed state. The United States, whatever, its problems is not in that league. The United States success as a state extends out from several factors, some of them good and others not so much. A mature citizen understands this. The immature citizen claims credit for all national accolades, while disavowing responsibility for all demerits. This specimen of patriotism is at the core of many (not all) arguments against reparations. Everyone claims to love their country, but considerably fewer know their country. This is true even among those charged with analyzing it:

Even assuming that invidious racism were an entirely negligible factor, it is likely that economic development will tend to proceed along broad racial channels if, for example, people of various ethnicities tend to largely marry within their ethnic group, live in neighborhoods largely populated by co-ethnics, and engage in other social-sorting behavior that is racial at its root but not really what we mean by the word “racism.” If that is the case — and it seems that it is — then initial conditions will be very important for a very long period of time.

This works if you believe in history as creationism. It does not work if you value research and evidence. Even at a time when people believed in separate European races, intermarriage rates among European ethnic groups were quite high. It's tough to assess intermarriage rates among blacks and whites in early America, partially because the very racial terms Williamson embrace did not have the same connotation. Nevertheless, the historian Ira Berlin notes that:

On the Eastern shore of Virginia, at least one man from every leading black family—the Johnsons, Paynes, and Drigguses—married a white woman. There seems to have been little stigma attached to such unions: after Francis Payne's death, his white widow remarried, this time to a white man. In like fashion, free black women joined together with white men. William Greensted, a white attorney who represented Elizabeth Key, a woman of color, in her successful suit for freedom, later married her. In 1691 when the Virginia General Assembly ruled against such relationships, some propertied white Virginians found the legislation novel and obnoxious enough to muster a protest have researched the history of American ethnicity.

What we term as "interracial" marriage did not just exist among the "propertied" but among the workers. In her book Sex Among The Rabble, the historian Clare Lyons quotes a Philadelphia minister denouncing "these frequent mixtures." The minister feared that "a particoloured race will soon make a great portion of the population of Philadelphia." The "particoloured race" did indeed come to be. It is us—black people. That unions between blacks and whites in America have historically been driven into the shadows is not a matter of "social sorting that is racial," "primitivism," nor "tribalism." It is a matter of Thomas Jefferson, in 1769, seeking to pass a law banishing any white woman from Virginia who had a child by black man. In short, it is matter of racist policy pushed my intelligent, and otherwise, sage men.

And racist policy is at the heart of our beloved country. Ignoring this leaves us intellectually poor, and finds us devolving bizarre thought experiments:

Imagine, for example, that rather than having been brought to the colonies as slaves, the first Africans to arrive in the New World had come as penniless immigrants in 1900.

Williamson then posits that black people would still be poor because they'd be far behind the native white population. Williamson never considers that the two groups might intermarry--because he believes in "race," which is to say creationism. For that same reason he ignores the fact there was no "New World" with "native whites" to come to without the labor of African-Americans. Europeans did not purchase enslaved Africans because they disliked the cut of their jib. They did it because they had taken a great deal of land and needed bonded labor to extract resources from it. Africans—aliens to society, existing beyond the protections of the crown—fit the bill.

"The people to whom reparations were owed," concludes. "Are long dead." Only because we need them to be. Mr. Clyde Ross is very much alive—as are many of the victims of redlining. And it is not hard to identify them. We know where redlining took place and where it didn't. We have the maps. We know who lived there and who didn't.

This was American policy. We have never accounted for it, and it is unlikely that we ever will. That is not because of any African-American's life-span but because of a powerful desire to run out the clock. Reparations claims were made within the natural lifetimes of emancipated African-Americans. They were unsuccessful. They were not unsuccessful because they lacked merit. They were unsuccessful because their country lacked the courage to dispense with creationism.

So it goes.

May 23, 2014

On Whose Shoulders the Research Stands

Over at Demos, there's an interview with Duke economist Sandy Darity, whose been researching and making the case for reparations long before I got the notion. Professor Darity is not alone in this. My argument for reparations stands on mountain of research produced by people whose labor does not always get the accolades it deserves. Frankly, it often gets ignored. I think there many reasons for that—JSTOR, the lack of incentive within the academy, the low level of curiosity among many journalists etc.

But whatever the reasons, there is something I must make absolutely clear: this piece would not exist without the work of economists like Professor Darity, of historians like Barbara Fields and Tony Judt, of sociologists like William Massey and Devah Pager, of law professors like Kim Forde-Mazrui and Eric J Miller. And so on. Without them, this blog, and all my writing, is significantly poorer. Without the academy, we are not talking right now.

I have no desire to be anybody's Head Negro—that goes for reparations and beyond. I just hope to write hard. In my own blogging, I've worked to link back to books, papers and studies that have influenced my thinking. I've really, really hoped—perhaps naively—that people would not stop with a blog post, or magazine article, that they click through the hyperlinks, and then form questions of their own.

At my heart, I am a failed academic. I was a history major at Howard University, dreaming of becoming the next Basil Davidson. (Or the next Robert Hayden. Long story.) But as a young man, I did not have the discipline to see the dream through. I found another dream but part of me is still back there. I have great respect and love for people who dig through the archives, who do the calculations, who do the case-studies, and perform the field research. As much as any of my ideas, I hope that love and respect passes on to some of you.

If you stop here, you are fooling yourself. Don't stop here. Don't go down so easy.

On Whose Shoulders The Research Stands

Over at Demos, there's an interview with Duke economist Sandy Darity, whose been researching and making the case for reparations long before I got the notion. Professor Darity is not alone in this. My argument for reparations stands on mountain of research produced by people whose labor does not always get the accolades it deserves. Frankly, it often gets ignored. I think there many reasons for that--JSTOR, the lack of incentive within the academy, the low level of curiosity among many journalists etc.

But whatever the reasons, there is something I must make absolutely clear: this piece would not exist without the work of economists like Professor Darity, of historians like Barbara Fields and Tony Judt, of sociologists like William Massey and Devah Pager, of law professors like Kim Forde-Mazrui and Eric J Miller. And so on. Without them, this blog, and all my writing, is significantly poorer. Without the academy, we are not talking right now.

I have no desire to be anybody's Head Negro--that goes for reparations and beyond. I just hope to write hard. In my own blogging, I've worked to link back to books, papers and studies that have influenced my thinking. I've really, really hoped--perhaps naively--that people would not stop with a blog post, or magazine article, that they click through the hyperlinks, and then form questions of their own.

At my heart, I am a failed academic. I was a history major at Howard University, dreaming of becoming the next Basil Davidson. (Or the next Robert Hayden. Long story.) But as a young man, I did not have the discipline to see the dream through. I found another dream but part of me is still back there. I have great respect and love for people who dig through the archives, who do the calculations, who do the case-studies, and perform the field research. As much as any of my ideas, I hope that love and respect passes on to some of you.

If you stop here, you are fooling yourself. Don't stop here. Don't go down so easy.

May 22, 2014

The Case for Reparations: An Intellectual Autopsy

The best thing about writing a blog is the presence of a live and dynamic journal of one's own thinking. Some portion of the reporter's notebook is out there for you to scrutinize and think about as the longer article develops. For me, this current article—an argument in support of reparations—began four years ago when I opposed reparations. A lot has happened since then. I've read a lot, talked to a lot of people, and spent a lot of time in Chicago where the history, somehow, feels especially present. I think I owe you a walk-through on how my thinking evolved.

When I wrote opposing reparations I was about halfway through my deep-dive into the Civil War. I roughly understood then that the Civil War—the most lethal conflict in American history—boiled down to the right to raise an empire based on slaveholding and white supremacy. What had not yet clicked for me was precisely how essential enslavement was to America, that its foundational nature explained the Civil War's body count. The sheer value of enslaved African-Americans is just astounding. And looking at this recent piece by Chris Hayes, I'm wondering if my numbers are short (emphasis added):

In order to get a true sense of how much wealth the South held in bondage, it makes far more sense to look at slavery in terms of the percentage of total economic value it represented at the time. And by that metric, it was colossal. In 1860, slaves represented about 16 percent of the total household assets—that is, all the wealth—in the entire country, which in today’s terms is a stunning $10 trillion.

Ten trillion dollars is already a number much too large to comprehend, but remember that wealth was intensely geographically focused. According to calculations made by economic historian Gavin Wright, slaves represented nearly half the total wealth of the South on the eve of secession. “In 1860, slaves as property were worth more than all the banks, factories and railroads in the country put together,” civil war historian Eric Foner tells me. “Think what would happen if you liquidated the banks, factories and railroads with no compensation.”

As with any economic institution of that size, enslavement grew from simply a question of money to a question of societal, even theological, importance.

I got that in 2011, from Jim McPherson (emphasis again added):

"The conflict between slavery and non-slavery is a conflict for life and death," a South Carolina commissioner told Virginians in February 1861. "The South cannot exist without African slavery." Mississippi's commissioner to Maryland insisted that "slavery was ordained by God and sanctioned by humanity." If slave states remained in a Union ruled by Lincoln and his party, "the safety of the rights of the South will be entirely gone."

If these warnings were not sufficient to frighten hesitating Southerners into secession, commissioners played the race card. A Mississippi commissioner told Georgians that Republicans intended not only to abolish slavery but also to "substitute in its stead their new theory of the universal equality of the black and white races."

Georgia's commissioner to Virginia dutifully assured his listeners that if Southern states stayed in the Union, "we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything."

An Alabamian born in Kentucky tried to persuade his native state to secede by portraying Lincoln's election as "nothing less than an open declaration of war" by Yankee fanatics who intended to force the "sons and daughters" of the South to associate "with free negroes upon terms of political and social equality," thus "consigning her [the South's] citizens to assassinations and her wives and daughters to pollution and violation to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans..."

This argument appealed as powerfully to nonslaveholders as to slaveholders. Whites of both classes considered the bondage of blacks to be the basis of liberty for whites. Slavery, they declared, elevated all whites to an equality of status by confining menial labor and caste subordination to blacks. "If slaves are freed," maintained proslavery spokesmen, whites "will become menials. We will lose every right and liberty which belongs to the name of freemen."

Enslavement is kind of a big deal—so much so that it is impossible to imagine America without it. At the time I was reading this I was thinking about an essay (which I eventually wrote) arguing against the idea of the Civil War as tragedy. My argument was that the Civil War was basically the spectacular end of a much longer war extending back into the 17th century—a war against black people, their families, institutions and their labor. We call the war "slavery." John Locke helped me with that.

This was all swirling in my head about the time I saw this article in the Times:

On Saturday, more than 15,000 students are expected to file into classrooms to take a grueling 95-question test for admission to New York City’s elite public high schools. (The exam on Sunday, for about 14,000 students, was postponed until Nov. 18 because of Hurricane Sandy.)

No one will be surprised if Asian students, who make up 14 percent of the city’s public school students, once again win most of the seats, and if black and Hispanic students win few. Last school year, of the 14,415 students enrolled in the eight specialized high schools that require a test for admissions, 8,549 were Asian.

Because of the disparity, some have begun calling for an end to the policy of using the test as the sole basis of admission to the schools, and last month, civil rights groups filed a complaint with the federal government, contending that the policy discriminated against students, many of whom are black or Hispanic, who cannot afford the score-raising tutoring that other students can. The Shis, like other Asian families who spoke about the exam in interviews in the past month, did not deny engaging in extensive test preparation. To the contrary, they seemed to discuss their efforts with pride.

I was sort of horrified by this piece, because what the complaint seemed to be basically arguing for was punishing a group of people (Asian immigrants) who were working their asses off. It struck me that these were exactly the kind of people you want if you're building a country. Even though I am arguing for reparations, I actually believe in a playing field—a level playing field, no doubt—but one with actual competition. It struck me as wrong to punish people for working really hard to succeed in that competition.

This paragraph, in particular, got me:

Others take issue with the exam on philosophical grounds. “You shouldn’t have to prep Sunday to Sunday, to get into a good high school,” said Melissa Santana, a legal secretary whose daughter Dejanellie Falette has been prepping this fall for the exam. “That’s extreme.”

I was stewing reading this. It offended some of my latent nationalism—the basic sense that you want everyone on your "team" to go out there and fight. But as I thought about it I felt that there was something underneath the mother's point. In fact there are people who don't "have to prep Sunday to Sunday, to get into a good high school." But they tend to live in neighborhoods that have historically excluded children with names like Dejanellie. Why is that? Housing policy. What are the roots of our housing policy? White supremacy. What are the roots of white supremacy in America? Justification for enslavement.

A few days later I sent the following rambling memo to my editor, Scott Stossel:

> Hey Scott. I have an essay that's starting to brew in me that I've been thinking a lot about. Are you at all interested in a piece that makes the case for reparations? This is totally pie in the sky, but it's my take on the Atlantic as a journal of "Big Ideas." There's this great piece in the Times a few weeks back about selective schools in New York and how Asian immigrants are dominating the process. I found myself really compelled by a lot of the stories and actually in more sympathy with the Asians (now Asian-Americans) than with the blacks who were protesting. A lot of what they were saying reminded me of the sort of stuff my own parents said.

>

> And then something occurred to me. The reason why a lot of these black parents are upset is because the schools are basically credentialing machines for the corridors of power. By not going to a Stuyvesant you miss out on that corridor, so the thinking goes. And moreso the feeling is (though never explicitly said) that black people deserve special consideration, given our history in this country. The result is that you have black parents basically lobbying for Asian-American kids to be punished because the country at large has never given much remedy for what it did to black people.

>

> I've thought the same before in reference to gentrification. The notion that DC should remain "black" has always struck me as really bizarre. Very little in America ever stays anything. Change is the nature of things. It only makes sense if you buy that black people are "owed" something. I.E. Since we never got anything for slavery, Jim Crow, red-lining, block-busting, segregation, housing and job discrimination, we at least deserve the stability of neighborhoods and cities we can call home.

>

> I'm thinking about it with the Supreme Court set to dismantle Affirmative Action. Isn't the "diversity" argument actually kind of weak? Isn't the recompensation argument actually much more compelling? Except this was outlawed with Bakke. What I am thinking is right now, at this moment, American institutions (especially its schools) are being asked to answer for the fact that country lacked the courage to do the right thing. In the wake of the Supreme Court's decision coming down, in the wake of (what looks like) a second Obama term, we could make a really strong case that now is the time renew a serious discussion about Reparations.

>

> And we could move it beyond "Check in hand" discussion to something more sophisticated. Does this interest you? I actually could see us arguing that Obama has nothing to lose, and should explicitly support such a policy. He ain't gonna do it. But we might--might--be able to make a good faith argument for it.

>

> Any interest?

All of this did not stick. (I don't, for instance, think it would be a good idea for Obama to support reparations. That would actually be a horrible idea.) But by then I had it fully established in my head that we are asking other institutions to answer for something major in our history and culture.

The final piece of this was the uptick in cultural pathology critiques extending from the White House on down. There is massive, overwhelming evidence for the proposition that white supremacy is the only thing wrong with black people. There is significantly less evidence for the proposition that culture is a major part of what's wrong with black people. But we don't really talk about white supremacy. We talk about inequality, vestigial racism, and culture. Our conversation omits a major portion of the evidence.

The final thing that happened was I became convinced that an unfortunate swath of popular writers/pundits/intellectuals are deeply ignorant of American history. For the past two years, I've been lucky enough to directly interact with a number of historians, anthropologists, economists, and sociologists in the academy. The debates I've encountered at Brandeis, Virginia Commonwealth, Yale, Northwestern, Rhodes, and Duke have been some of the most challenging and enlightening since I left Howard University. The difference in tenor between those conversations and the ones I have in the broader world, are disturbing. What is considered to be a "blue period" on this blog, is considered to be a survey course among academics. Which is not to say everyone, or even mostly everyone, agrees with me in the academy. It is to say that I've yet to engage a historian or sociologist who's requested that I not be such a downer.

This process was not as linear as I'm making it out to be. But it all combined to make me feel that mainstream liberal discourse was getting it wrong. The relentless focus on explanations which are hard to quantify, while ignoring those which are not, the subsequent need to believe that America triumphs in the end, led me to believe that we were hiding something, that there was something about ourselves which were loath to say out in public. Perhaps the answer was somewhere else, out there on the ostensibly radical fringes, something dismissed by people who should know better. People like me.

How to Comment on Reparations

Here is your uncurated space to talk about reparations. Later we will have a curated space according to the usual rules on my blog. Even though this is uncurated—it is still moderated. In other words, you still have to obey basic Atlantic rules of commenting. No one will try to steer the conversation, but namecalling and blatant trolling will still bring the pain of banhmmer.

Think of this as Hamsterdam. But what happens in Hamsterdam, must stay in Hamsterdam.

May 21, 2014

"So That's Just One Of My Losses"

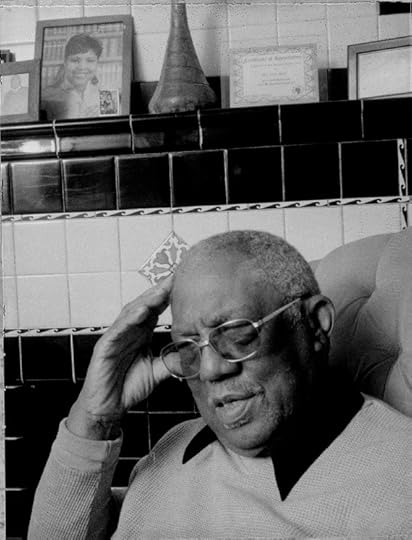

World War II veteran and Mississippi native Clyde Ross. Photographed by Carlos Javier Ortiz in his North Lawndale home.

World War II veteran and Mississippi native Clyde Ross. Photographed by Carlos Javier Ortiz in his North Lawndale home.Last year, I went to visit the home of Clyde Ross in North Lawndale. I was there to research an argument for reparations. Clyde Ross had just turned 90. I asked Mr. Ross why he'd come from Mississippi to Chicago. He told me he came because he was seeking "the protection of the law." I didn't understand what he meant. He told me there were no black judges, no black police, no black prosecutors in his hometown of Clarksdale. For a black man living in that town it effectively meant that there was "no law."

This was a particularly illustrative example of why it is always important to report. Talking to Ross clarified something I'd been thinking about--specifically that being black was not a matter of white people thinking you had cooties. It was something deeper and more mature. It was the branding of black people as outside of American society, outside of American law, and outside of the American social contract. And this branding was done even as black people pledged fealty to the state, paid taxes to the state, and died for the state. This was high tech robbery, plunder at the systemic level. White Supremacy was not about getting black and white people to sit at the same lunch table, it was about getting white people to stop stealing shit from black people--labor, bodies, children, taxes, lives.

Liberals intellectuals and pundits have spent the past few years dancing around this historically demonstrable fact. I rarely hope for my writing to have any effect. But I confess that I hope this piece makes people feel a certain kind of way. I hope it makes a certain specimen of intellectual cowardice and willful historical ignorance less acceptable. More I hope it mocks people who believe that a society can spend three and a half centuries attempting to cripple a man, fifty years offering half-hearted aid, and then wonder why he walks with a limp.

For two years now people have asked me for an answer. You know have it. For that you should thank The Atlantic, for its largess. Specifically, you should thank Scott Stossel, Sam Price-Waldman, James Bennet, Clare Sestonovich Ellie Smith, Joe Pinsker, Darhil Crooks, John Gould, Bob Cohn, Paul Rosenfeld, Kasia Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg, Clare Sestanovich, Janice Cane, Carlos Javier Ortiz, Corby Kummer and many more.

I hope this is the start of a long conversation. I made my argument from the perspective of housing, but I strongly suspect that reparations arguments could be made from the perspective of criminal justice, education, health care or from any number of angles. For writers out there interested in this I can only quote the words of a brave man--Drop it now. The people are ready.

'So That's Just One of My Losses'

Last year, I went to visit the home of Clyde Ross in North Lawndale. I was there to research an argument for reparations. Ross had just turned 90. I asked him why he'd come from Mississippi to Chicago. He told me he came because he was seeking "the protection of the law." I didn't understand what he meant. He told me there were no black judges, no black police, no black prosecutors in his hometown of Clarksdale. For a black man living in that town it effectively meant that there was "no law."

This was a particularly illustrative example of why it is always important to report. Talking to Ross clarified something I'd been thinking about—specifically that being black was not a matter of white people thinking you had cooties. It was something deeper and more mature. It was the branding of black people as outside of American society, outside of American law, and outside of the American social contract. And this branding was done even as black people pledged fealty to the state, paid taxes to the state, and died for the state. This was high-tech robbery, plunder at the systemic level. White supremacy was not about getting black and white people to sit at the same lunch table, it was about getting white people to stop stealing shit from black people—labor, bodies, children, taxes, lives.

Liberals, intellectuals, and pundits have spent the past few years dancing around this historically demonstrable fact. I rarely hope for my writing to have any effect. But I confess that I hope this piece makes people feel a certain kind of way. I hope it makes a certain specimen of intellectual cowardice and willful historical ignorance less acceptable. More, I hope it mocks people who believe that a society can spend three-and-a-half centuries attempting to cripple a man, 50 years offering half-hearted aid, and then wonder why he walks with a limp.

For two years now people have asked me for an answer. You now have it. For that you should thank The Atlantic, for its largess. Specifically, you should thank Scott Stossel, Sam Price-Waldman, James Bennet, Ellie Smith, Billy Brennan, Joe Pinsker, Darhil Crooks, John Gould, Bob Cohn, Paul Rosenfeld, Kasia Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg, Clare Sestanovich, Janice Cane, Karen Ostergren, Carlos Javier Ortiz, Corby Kummer, and many more.

I hope this is the start of a long conversation. I made my argument from the perspective of housing, but I strongly suspect that reparations arguments could be made from the perspective of criminal justice, education, health care, or from any number of angles. For writers out there interested in this I can only quote the words of a brave man: Drop it now. The people are ready.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17153 followers