Jacqueline Pearce's Blog, page 4

April 11, 2013

Haiku, or not?

What is haiku? Many people think it is simply a short three-line poem of 5-7-5 syllables. But please forget this definition! It leads to things like:

that song was poppin

hari ini tdr gk ya?

Sorting the bedroom

-Haiku Robot

or

Haikus are easy

but sometimes they don’t make sense

Refrigerator

-anonymous

What is a haiku, really? Haiku is a very short form of poetry (originally Japanese) that aims to capture the essence of something. It uses simple, direct language to point to a thing or moment (usually in nature), while at the same time implying something more. Traditional haiku contains three main elements:

- a kigo (seasonal reference)

- a kireji (cutting word, symbol, or pause, that divides the haiku into two juxtaposed parts)

- 17 on (17 Japanese sound units), with the poem usually broken into three phrases of 5-7-5 on (written in Japanese as one or two vertical lines)

Today, haiku are written all over the world in many different languages, including English (the word “haiku” is both singular and plural).

The 17 Japanese on sounds do not actually correspond to English syllables (for example, the word “on” itself, which English-speakers would view as a single syllable, comprises two on). Translating a Japanese haiku into 17 English syllables actually makes the haiku longer than it was meant to be. For example, a famous haiku by the 17th century Japanese poet Basho was originally written using 17 on, but it is translated:

old pond…

a frog leaps in

water’s sound

To translate it into 17 English syllables would make it too cumbersome, moving away from the original intent of the poem. Here’s an example (from the Wikipedia haiku page):

at the age old pond

a frog leaps into water

a deep resonance

It’s the simplicity and directness of the first translation (and the original haiku) that catches the reader’s attention and leaves the reader room to see the moment for him or herself. In fact, it’s haiku’s simplicity ─its ability to focus the reader in on a precise, concrete “a-ha” moment─ that makes it so appealing to many haiku-lovers. Simplicity keeps the moment fresh. Any added decoration, metaphor or explanation entangles the reader; gives you so much that there is nothing to stop and think about. The simple wording engages your imagination. You pause and hear the sound of the water as the frog’s body breaks the surface. But the simply written haiku can also imply emotion and allude to deeper meaning. The “old pond,” for example, can be read as a reference to Basho, himself, an old poet still moved by the world around him.

So, the idea that English haiku should be written in 17 syllables is not actually correct, and throwing a bunch of words together into three lines of 5-7-5 syllables (even if they are poetically written, rather than generated by a robot) does not make those lines a haiku. To be a real haiku, a poem has to have some or all of the elements mentioned above (seasonal reference, simplicity, and also a juxtaposition or a space between images that suggests something deeper). In other words, “That song was poppin” is not a haiku.

Here are a few haiku I’ve come across recently that I really like (my favorite haiku are always changing):

evening walk

the faded leash

I can’t throw out

-John Soules

abandoned farm

still there, the scents

in the barn

-George Swede

graveside

forming one shadow

with my sister

-Tom Painting

solo hike─

slowly catching up

with myself

-Annette Makino

You’ll notice that none of them have 5-7-5 syllables. But yes, all of them are haiku.

I hope this post doesn’t sound like an anti-5-7-5 rant. Like many people, I grew up thinking English haiku had to be written as three lines of 5-7-5 syllables (you’ll find many haiku written this way in my earlier blog posts), and I wasn’t really conscious of the other elements of good haiku, other than the seasonal reference. I wrote and read haiku intuitively, I guess (with mixed results). I still write this way, but I’ve also been making an effort to think more about haiku, how it works, and what makes a good haiku (which leads to more re-writing), and I’ve come across an awful lot of writing that calls itself haiku, but is not. This pseudo-haiku is sometimes interesting writing forced to fit the 5-7-5 format (often with the first sentence ending in the middle of the second line), or even good poetry with intriguing metaphors, but it’s not haiku. The main point I want to make here is that haiku is about more than syllable count (I’m talking to you, Haiku Robot, children’s book publishers of stories written in so-called “haiku” format, companies that hold “haiku” slogan contests to advertise new products, and anyone who leaves comments on haiku blogs complaining that the haiku is not real haiku because the syllable count isn’t right).

Okay, maybe this is an anti-5-7-5 rant.

Anyway, if you want to learn more about haiku, here are some good websites and blog posts to check out:

Haiku on Wikipedia (good explanation of haiku and the issues around syllable count)

Graceguts, the website of haiku poet, Michael Dylan Welch (contains examples of haiku, articles, and links to other resources)

Haiku checklist (helpful for thinking about and revising your own haiku)

Haiku journey of poet Ferris Gilli (many good insights into how to write haiku)

How to write bad haiku (a fun post that looks at what makes a haiku “bad” or “good”)

Kireji and kigo (cutting word & seasonal reference)

More on juxtaposition and seasonal references

February 1, 2013

Things are looking up

It’s been a grey rainy week here in Vancouver, but downtown today, I had an unexpected glimpse of cherry blossoms and sunshine ─appropriate for the start of National Haiku Writing Month (February, the shortest month for the shortest poetic form).

early blossoms─

a new spring

in my step

Click here for more info on National Haiku Writing Month (NaHaiWriMo).

January 1, 2013

First haiku of the new year

November 23, 2012

Inspired by fall leaves and history

I thought I’d share a glimpse into the wonderful writing retreat I experienced last month at Spark Box Studio near Picton Ontario (with funding gratefully received from the Canada Council!). A whole week without distractions, focusing on the craft of writing historical picture books! I was particularly interested in exploring the question, “How do I take a huge topic such as the War of 1812 and hone in on a small story suitable for children?”

I thought I’d share a glimpse into the wonderful writing retreat I experienced last month at Spark Box Studio near Picton Ontario (with funding gratefully received from the Canada Council!). A whole week without distractions, focusing on the craft of writing historical picture books! I was particularly interested in exploring the question, “How do I take a huge topic such as the War of 1812 and hone in on a small story suitable for children?”

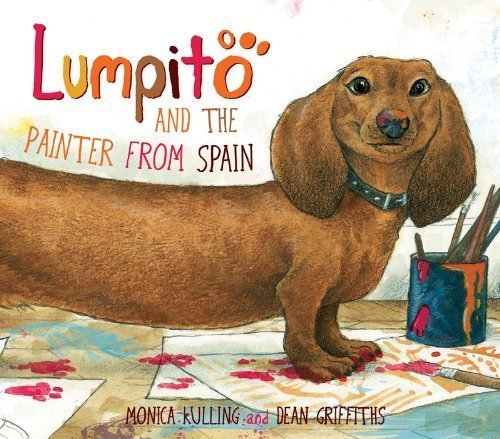

To help me get on the right footing for my retreat, I stopped in Toronto beforehand to meet with children’s  book author Monica Kulling, for a thoughtful and inspiring discussion about writing historical stories for children. Her latest book, Lumpito and the Painter from Spain, about a little dog who touched the life of Pablo Picasso, was hot off the press, and provided a great example (I love the dog, illustrated by Dean Griffiths).

book author Monica Kulling, for a thoughtful and inspiring discussion about writing historical stories for children. Her latest book, Lumpito and the Painter from Spain, about a little dog who touched the life of Pablo Picasso, was hot off the press, and provided a great example (I love the dog, illustrated by Dean Griffiths).

Next, I took a side trip to soak up some War of 1812 history and watch the reenactment of the Battle of Queenston Heights near Niagara Falls. The  boom of cannons, smell of smoke, calls of the soldiers, costumes of the military and civilian reenactors, and the cool, damp fall day helped to cast a spell that opened a window into the past.

boom of cannons, smell of smoke, calls of the soldiers, costumes of the military and civilian reenactors, and the cool, damp fall day helped to cast a spell that opened a window into the past.

At Spark Box Studio, I started each day with a solitary walk between farmers’ fields. The empty fields, subdued colours, and the whispers and rustles of leaves and grasses that followed me as I walked, made it easy to imagine a young girl two hundred years in the past, standing on the edge of a field, hearing  the distant boom of cannon and cracks of musket fire. I felt like I was walking with one foot in the present and one in the past as I wrote these haiku:

the distant boom of cannon and cracks of musket fire. I felt like I was walking with one foot in the present and one in the past as I wrote these haiku:

autumn wind─

on the lonely path

many voices

&

whispering grasses─

the words always

out of reach

While it was great to have so much time to myself to think and write, talking with the creative hosts and other guests at Spark Box Studio was also enriching. And, despite that last haiku, the words weren’t out of reach. I finished the first draft of a picture book story and concluded the retreat feeling buoyed in spirit, recharged and reinspired to continue writing…

August 10, 2012

Artsy Fartsy stuff for sale

Several local artists & craftspeople will be selling stuff. Here’s a glimpse of some rubber stamps, Japanese papers & other collage items I’ll be parting with:

July 30, 2012

The artful rusty tractor

My father-in-law has what you might call an en plein air tractor shop (or graveyard, depending on your point of view). Yesterday, in the low-angled sun of early evening, the rusting tractors seemed to speak of nostalgia for a disappearing way of life and, at the same time, to take on a new and different life through their wonderful colours, textures and shapes.

July 18, 2012

Hello Kitty graffiti

It’s been awhile since I posted any graffiti images, but I couldn’t resist sharing this photo I took at Vancouver’s Commercial Drive Skytrain station a couple days ago. Who put the friendly feline there? How? Why? Were they trying to spread cheerful cuteness, or saying something more cynical?

June 25, 2012

Flood Warnings!

Recent flood alerts along the Fraser River feel like deja vu. This year’s delayed mountain snow melt combined with extra rain have made for conditions similar to those in spring 1948, when my new chapter book, Flood Warning, takes place. But, while the story might be too close to reality for some communities this week, the worse threats seems to be over in most locations –at least for now. You can read flood news here.

Recent flood alerts along the Fraser River feel like deja vu. This year’s delayed mountain snow melt combined with extra rain have made for conditions similar to those in spring 1948, when my new chapter book, Flood Warning, takes place. But, while the story might be too close to reality for some communities this week, the worse threats seems to be over in most locations –at least for now. You can read flood news here.

If you’re interested in sharing this story with kids, please ask for the book at your local bookstore, or order from these amazon.com or amazon.ca links (thanks!). You can find info about my other books for kids on my website.

May 21, 2012

Fraser River flood flashback (and book giveaway)

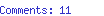

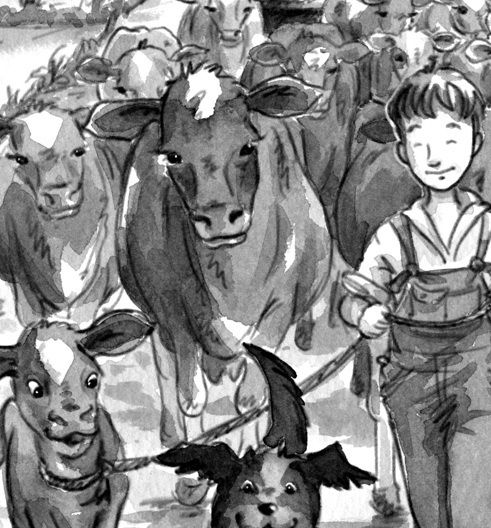

On this day in 1948*, the town of Agassiz’s Victoria Day dance was interrupted by news that the Fraser River was about to flood. Men, young and old, quietly left the dance to build up the sandbag dyke along the river and begin what would inevitably be a lost battle to keep the water back and protect their homes, farms and businesses. A few days later, children waded through waist deep water on the school grounds, men rowed boats down the main street of town, and hundreds of dairy cows choked the road west of town as farmers herded them to higher ground, murky water licking at their heals.

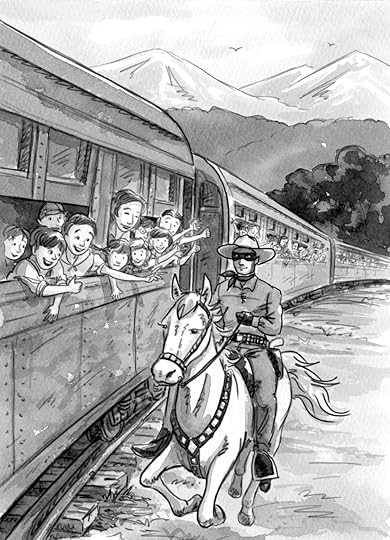

On this day in 1948*, the town of Agassiz’s Victoria Day dance was interrupted by news that the Fraser River was about to flood. Men, young and old, quietly left the dance to build up the sandbag dyke along the river and begin what would inevitably be a lost battle to keep the water back and protect their homes, farms and businesses. A few days later, children waded through waist deep water on the school grounds, men rowed boats down the main street of town, and hundreds of dairy cows choked the road west of town as farmers herded them to higher ground, murky water licking at their heals.Tom, the main character of my new chapter book, Flood Warning, wishes he could join his father and the other men fighting the flood. He’s sure his favorite radio hero, the Lone Ranger, would do no less. At the very least,  the Lone Ranger on his firy horse, Silver, would escort the evacuation train safely out of town. But Tom has to go to school, and when school is dismissed early, he has to stay home and help his mom around the house. Until the flood comes to him, and Tom must become a real-life hero and help save his family’s dairy cows. (Info on book giveaway at bottom of post.)

the Lone Ranger on his firy horse, Silver, would escort the evacuation train safely out of town. But Tom has to go to school, and when school is dismissed early, he has to stay home and help his mom around the house. Until the flood comes to him, and Tom must become a real-life hero and help save his family’s dairy cows. (Info on book giveaway at bottom of post.)

The story, while fiction, is based on what really happened during the 1948 flood. Agassiz was the first town to be evacuated (read Flood Warning for the unusual role played by the town cemetery), but communities all along the Fraser Valley were affected. In total, 30,000 civilians (local farmers, townspeople, and volunteers from other areas) sprang into action to fight the flood, rescue stranded people and animals, and bring in supplies. Sixteen thousand people (including 3,800 children) were forced to flee, and hundreds of animals were also removed to safety (750 cows were  evacuated in Agassiz alone). Roads (including the Trans Canada Highway) and railways were swamped, people who remained in the flooded areas were cut off from the rest of the world, and even the city of Vancouver was isolated from the rest of the country except by plane.

evacuated in Agassiz alone). Roads (including the Trans Canada Highway) and railways were swamped, people who remained in the flooded areas were cut off from the rest of the world, and even the city of Vancouver was isolated from the rest of the country except by plane.

When the water finally began to recede two weeks later, it left devastation in its wake. Orchards and field crops were destroyed, debris was everywhere, floor boards of houses, cupboards, stairs, etc. were warped and rotting, carpets were ruined, walls stained, water-soaked furniture falling apart, and dark stagnant water and mud remained stuck in low areas. Yet, throughout the ordeal, there was a sense of camaraderie and mutual support, and people’s spirits remained high.

For more information on the Fraser River flood, Nature’s Fury, a first-hand account by newspaper correspondents and photographers who witnessed the flood, is available to download from the city of Chilliwack’s website.

Check out Flood Warning for a child’s eye view.

I’m giving away a signed copy of Flood Warning along with a bookmark, special button, and a DVD that includes episodes of the 1950s Lone Ranger TV show. Add a comment here, or “Like” my Facebook page to be entered in the draw. (Draw deadline: June 15, 2012.)

Of course, you can also ask for the book at your local bookstore, or order it through Amazon.com, Amazon.ca and other online sources.

Flood Warning is part of the Orca Echoes series for grades 1-3 and is illustrated by Leanne Franson (Leanne also illustrated my previous chapter book, Mystery of the Missing Luck, and I love her work).

* Note: Today is Victoria Day here in Canada, and it was on Victoria Day in 1948 that the flood warning began, however, in 1948 Victoria Day fell on May 24th.

May 16, 2012

Spring haiku experiment

I’ve been in a bit of a haiku slump this past year, but lately I’ve felt reinspired –thanks to the onset of spring and to a reaffirming talk by haiku poet Michael Dylan Welch at VanDusen Garden’s Sakura Days Fair.

One of the things Michael mentioned in his talk is the idea that a good haiku should not tell the reader what to think, but instead, “trigger” the reader’s emotional and imaginative response, or open a door for the reader to step through into the experience (kind of like the haiku is a partnership between writer and reader –part is supplied by the writer and the rest by the reader).

Below are a few of my new haiku (along with some related photos that I think are made sort of haiku-like through cropping). I don’t know if any of these poems achieve what Michael describes, but I thought I’d share them anyway. One of the things I try to do with my haiku is to simply be honest to the moment, and so if a kireji (“cutting word” or contrast) feels right, I include it. If the haiku doesn’t want to do anything but revel in the sensual experience of the moment, I let it. I’m trying to move away from the 5-7-5 syllable habit to sparer lines, but sometimes I have success, sometimes I don’t. If the poems resonate in any way for anyone else out there, I’d be interested to know.

pink dogwood blossoms

gazing at the moon

a dream slips away

now the lilacs

third course of spring

feast of scents

blue sky

jumping on trampoline

blue sky