Randal Rauser's Blog, page 171

September 24, 2015

The point is to become holy. Happiness comes later: Christianity Against Culture Part 2

Imagine that the eager young campers arrive for their first day of summer camp. The campers believe they are at the camp to have fun. Unbeknownst to them, however, their parents have sent them there to remediate their behavior. You see, this camp deals with delinquent youths, and while it aims to offer fun, the overriding purpose of the camp is to turn the young campers into good citizens. The point is not merely to offer a series of enjoyable activities.

Imagine that the eager young campers arrive for their first day of summer camp. The campers believe they are at the camp to have fun. Unbeknownst to them, however, their parents have sent them there to remediate their behavior. You see, this camp deals with delinquent youths, and while it aims to offer fun, the overriding purpose of the camp is to turn the young campers into good citizens. The point is not merely to offer a series of enjoyable activities.

Many people today are like those young campers. That is, they believe that while in this mortal coil we’ve been granted certain unalienable rights, and that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

But while the Christian has nothing against happiness, she also recognizes that there is a distinct disorder afoot and remediation and reformation must occur. In short, the pursuit of happiness must be subverted to another pursuit: holiness.

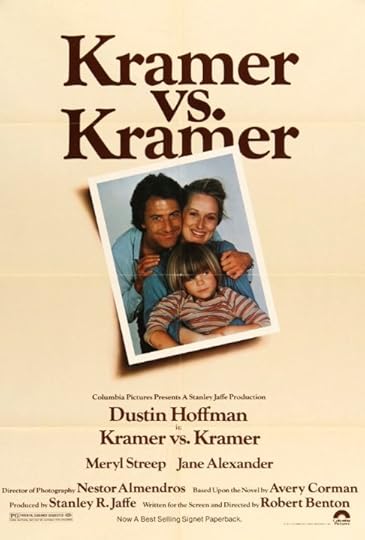

Let’s put this in concrete terms. In the 1979 film “Kramer vs. Kramer” Joanna Kramer leaves her husband Ted (and her young son) and heads out west in search of happiness. The separation and subsequent divorce are justified in Joanna’s mind by her conviction that she cannot be happy in this marriage.

No doubt, Ted is not an ideal mate, but then who is? Joanna came into that marriage with the expectation that she was to be happy. After all, that’s what we find with the romanticized (and, it must be said, infantilized) conception of marriage as a never-ending torrid love affair. And so when Joanna wasn’t happy, bitter disappointment ensued, followed by the crushing impact on her husband and child when she simply walked away.

What if Joanna had instead viewed her marriage to Ted as an opportunity for growth in holiness? Yeah, I know, that’s definitely not romantic. Viewing Ted’s weaknesses and limitations (and Joanna’s inevitable disappointments) as an opportunity for personal growth in moral virtue is not the stuff of romance.

But it is reality.

The Christian vision doesn’t deny happiness. But it does subvert it to the primary goal of holiness. And ironically enough, from the Christian perspective, this prioritization itself provides a far greater and more profound promise of long-term abiding happiness than the shallow pursuit of one’s immediate base desires.

September 23, 2015

The Making of an Enemy? The Tuggy-Spiegel Interview on Atheism

This week on the Trinities Podcast Dale Tuggy interviewed James Spiegel on his 2010 book The Making of an Atheist: How Immorality Leads to Unbelief.

Since my new book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? is one long rebuttal to folks like Spiegel, I listened to the interview with some interest. (You can read my earlier review of Spiegel’s book here.) And after listening, I wrote the following response.

The Rebellion Thesis

Spiegel and Tuggy begin with a discussion of Alvin Plantinga’s epistemology which has been formative in the development of Spiegel’s ideas. Spiegel observes that for Plantinga,

“sin is one of the important ways that our cognitive faculties get hampered and things can become so hampered by sin that we find ourselves even denying what should be clear to everyone regarding the reality of God…” (3:21)

So the claim is that God’s existence should be clear to everyone, and the reason it isn’t is due to sin. Note that Spiegel didn’t simply attribute that lack of clarity to original sin (a state of cognitive malfunction brought about in the past which affects all current human beings). Rather, he attributes it at least in part to personal sin, i.e. the morally culpable actions of human beings who somehow sabotage their own cognitive faculties (or the deliverances thereof).

Spiegel summarizes his core thesis in two parts:

“atheism is not the result of a lack of evidence or a failure on God’s part to make him clearly enough known in creation and human experience such that … everybody can see that it’s so.”(14:06)

“the atheistic position is the product of, to some degree, immorality, … that immorality somehow leads to unbelief” (14:26) “in some way the will is involved” (14:28)

Later in the interview, Tuggy presses Spiegel by asking about the hypothetical 9th grader in Sweden who has simply never had an opportunity or inclination to consider God as a live option for belief. Is that 9th grader’s atheism also the result, to at least some degree, of the sinful, morally culpable will of the child to reject God?

Spiegel insists that yes, this child is also in rebellion against God. As he put it earlier in the interview: “I intend it as a universal thesis.” (18:35) To be sure, “For some people it may be less willful than for others, but I do think the will is involved to some degree in every case” (19:20)

In short, Spiegel believes that in all instances, atheism is attributable at least in part to a sinful, rebellious human will which refuses to acknowledge the clear revelation of God.

What is an atheist?

Spiegel defines “atheism” broadly as “the denial of theism”. Note that this definition is sufficiently broad to encompass both belief in the non-existence of God (in other words, that which is typically called “atheism”) and a failure to believe in the existence of God (a cognitive state which encompasses agnosticism as well). As Spiegel says, “The biblical diagnosis … applies to all forms of rejection of theism” (15:32)

“Atheism,” Spiegel says, is “a rejection of theism, a definite disbelief in God”. (16:29) And that rejection can be expressed either as atheism or agnosticism. In other words, any failure to accept the proposition that God exists is explicable at least in part due to sinful rebellion.

An extraordinary claim in search of extraordinary evidence

So that’s the claim. Now let’s talk about the evidence for it.

Imagine that you encountered a book titled The Making of a Welfare Recipient: How laziness leads to welfare. Intrigued, you read the description on the back. And you discover that the author is arguing that in all cases welfare recipients are on the dole because they are, to some degree, lazy. This is an extraordinary thesis! And one would expect that the author better have some good evidence to back it up.

Similarly, if Spiegel wants to argue that every instance of atheism and agnosticism — every instance of a person failing to affirm the proposition “God exists” — is due at least in part to morally culpable, sinful rebellion, he better have some good evidence to back it up.

So what kind of evidence does he provide?

Personal anecdotes

To begin with, Spiegel recounts anecdotal reports that Christian converts from atheism report that they were culpably suppressing belief in God while they were atheists. This is how Spiegel describes these folk accounting for their own previous state of unbelief:

“I was lying to myself, or I knew God was there all along. I just didn’t want to accept this. It was a kind of suppression of that belief or truth that I was aware of.” Often this is because “I didn’t want to acknowledge that I was going to be accountable.” (20:53)

This kind of testimony may support the thesis that some atheists are in rebellion against God. By the same token, the testimony of some former welfare recipients that they were on welfare because they were lazy provides evidence that some welfare recipients are on welfare because they are lazy.

But Spiegel is not merely arguing about the state of rebellion in some atheists. Rather, he’s arguing a universal thesis that all instances of atheism are the result of sinful rebellion. And in support he cites some personal anecdotes.

Can you imagine if the hypothetical author of The Making of a Welfare Recipient attempted to justify his thesis with vague personal anecdotes about former welfare recipients? Would Spiegel think this was evidence for a universal claim about all welfare recipients?

Later in the interview Spiegel also references Paul Vitz, the Christian psychologist who argued in Faith of the Fatherless that atheistic belief could be attributable to the poor relationships that people had with their fathers. Once again, this may be the case for some atheists, but it provides perilously weak evidence for a universal thesis about all atheists (and agnostics).

Citing Romans 1

The only other evidence Spiegel proffers for his rebellion thesis is found in his appeal to Romans 1 where Paul writes:

“18 The wrath of God is being revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of people, who suppress the truth by their wickedness, 19 since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. 20 For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.”

As Spiegel puts it, this reference to “the suppression by wickedness” provides “The biblical evidence” to justify the universal thesis.

That’s it.

In fairness, during the interview, Spiegel also makes passing reference to Ephesians 4. And in his book he includes a smattering of other biblical texts. But none of these passages justify his universal thesis. In fact, the only passage that would seem to provide that direct evidence comes here in Romans 1.

Consequently, Spiegel ultimately argues that all instances of atheism and agnosticism are rooted in sinful rebellion based on this single passage from Romans 1.

Let’s put this in some perspective.

This is akin to arguing that no woman should be allowed to deliver a university lecture to any males based on 2 Timothy 2:

“11 A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. 12 I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. 13 For Adam was formed first, then Eve. 14 And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner.”

It’s also like claiming that Christians will not be harmed by the consumption of antifreeze based on a citation from Mark 16:18:

“17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: In my name they will drive out demons; they will speak in new tongues; 18 they will pick up snakes with their hands; and when they drink deadly poison, it will not hurt them at all; they will place their hands on sick people, and they will get well.”

In all three cases, an extraordinarily ambitious, high stakes thesis is justified by a single biblical citation. If Spiegel would reject the latter two citations as grossly inadequate to justify such an extraordinarily ambitious, high stakes thesis, why does he think the single citation of Romans 1 is adequate to justify his extraordinarily ambitious high stakes thesis?

The Making of a Doubter

Spiegel calls his book The Making of an Atheist. But as he notes above, his argument extends to agnostics as well. Indeed, anybody who fails to affirm that God exists is in rebellion against God, “since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.”

As a result, Spiegel would have been clearer had he titled his book The Making of a Doubter: How immorality leads to doubt, since his ultimate target is not belief that God doesn’t exist, but rather failure to believe that God does exist.

And that’s where the problems get worse. As I point out in Is the Atheist My Neighbor?, the problem at this point is that this reading of Romans 1 indicts not merely the failure to believe that God exists, but also the failure to believe with adequate conviction that God exists.

Consider the following illustration. Imagine that Dave says the neighbor’s convertible is blue, but Scott says it is orange. After some heated discussion, Dave and Scott walk outside to settle the debate. Dave is right: the convertible is bright blue. Now imagine Scott responds by squinting and reluctantly saying, “I guess it probably is blue, but one could certainly mistake it for orange.”

Maybe this is the best concession Scott can muster, but it appears to indicate a sore loser. After all, the evidence for the car’s blueness is overwhelming for any honest observer. Scott’s grudging concession is simply inadequate in light of the overwhelming evidence that he is wrong.

The person who agrees that God exists, but who grants the truth of that proposition less conviction than the evidence warrants, is culpable like Scott with his qualified admission of the car’s blueness.

And who might that be?

Well consider, for example, any Christian who has ever harbored doubts about the nature or existence of God. Consider any Christian who has ever dared ask “God, are you really there? Do you really care?” Consider any Christian who has worried that God might not be there. That’s a lot of Christians.

And according to the consistent application of Spiegel’s reading of Romans 1, at that moment every one of those doubts is due at least in part to sinful rebellion against the plain and clear divine revelation to God’s existence and nature.

Conclusion

James Spiegel seems like a genuinely amiable person. But he wrote a book that defends an extraordinary thesis which suffers from a dearth of evidence and morally indicts every person who has ever harbored a doubt about God’s existence and/or nature.

In the interview Spiegel notes that the reaction to his thesis from the atheist community has been largely hostile. No surprise there. I said above that Spiegel might better have titled his book The Making of a Doubter. But where the atheist community is concerned, he might best have called it The Making of an Enemy.

September 21, 2015

Rethinking short-term missions … and other forms of voluntourism

Short-term mission trips are big business. According to a recent article in Relevant Magazine, every year in the United States more than 1.5 million people spend close to $2 billion going on a short-term mission trip. Indeed,over the last several years these trips seem to have become something of a rite of passage for young Christians to solidify their faith while making an intensive two week (or more) contribution to the Kingdom of God.

However, a growing number of Christians have been expressing reservations about the trend. While I recognize the good in short-term missions, I’ve also had my concerns. I gained further clarity on my own concerns recently while watching a CBC Doc Zone documentary called “Volunteers Unleashed” which examines the growing industry of “voluntourism” which integrates volunteering in a foreign territory as part of a vacation experience. It would appear that short-term missions is a Christian version of voluntourism, and many of the problems with the practice generally would be concerns with short-term missions as well.

If you’re thinking about a short-term mission for yourself or somebody else, you might want to view the documentary as part of your preparation. The two articles I linked to above would be helpful as well. Short-term missions are neither all good nor all bad: instead, as with so much in life, the truth lies somewhere in between.

You can visit the website for “Volunteers Unleased” here or watch it below at a YouTube link.

September 20, 2015

The Rights of the Creator

Let’s take a look at one of the responses to my article “You Don’t Own Yourself: Christianity Against Culture Part 1“. Andy Schueler writes:

“Lets assume that it would be possible to create an artificial life form that is very human-like, like Mr. Data from Star Trek or the Replicants in Blade Runner. Would you then say that these artificial people do not own their lives, but that their lives are rather only a loan from some engineers who have the right to reclaim their ‘gift’ if they want to? And if not, why not?”

At the outset we should acknowledge a philosophical problem posed by Andy’s thought experiment. I speak here of the so-called Zombie problem in philosophy of mind. And no, this is not a reference to undead human beings with an insatiable desire for human brains. Rather, it refers to the possibility that extremely effective AI could act as a conscious human being whilst lacking any conscious (let alone self-conscious) life.

But let’s set aside the Zombie problem and assume that a corporation does create a conscious organism. What then, of Andy’s question?

Since Andy wishes this to be an analogy with God’s divine ownership, let’s maximize the continuity. To do that we should begin by supposing that the corporation is supremely benevolent and wise. Thus, we can suppose that however the corporation will act, it will always be in a way consistent with supreme benevolence and wisdom. Thus, they will never act in a capricious manner, as might be suggested by Andy’s reference to “the right to reclaim their ‘gift’ if they want to”.

Next, let’s add that the AI was not merely created by the corporation, but is sustained in existence by that corporation every moment through the benevolent actions of the corporation.

Does the corporation maintain some significant rights of ownership over the AI organism they produced? If we thought otherwise, what would be our basis for thinking this?

September 18, 2015

You Don’t Own Yourself: Christianity Against Culture Part 1

Several weeks ago, blog commenter extraordinaire Luke Breuer posed the following question to me in a discussion thread:

“What are some of the ways you think Christianity [strongly?] contrasts with contemporary culture?”

It’s an interesting question, not least because I spend a lot of my time emphasizing the points of continuity between Christianity and contemporary culture. But there is also value in highlighting the points of discontinuity, and so I’m devoting a brief series to that topic.

For starters, I think the starkest contrast is likely centered on the question: who owns my body (or my person or my life)? In contemporary culture there is a very strong emphasis on individualism and individual bodily autonomy. I own my body, and it is offensive and all but inconceivable that one might suggest otherwise. This belief often expresses itself in the sentiment that I can do what I want with myself so long as I do not hurt others.

But in a Judeo-Christian picture of the world, you do not have that kind of autonomy because you do not own your own life and you are not the master of your own destiny. Indeed, if I may put this bluntly, your life is on loan, a gift from your creator, a bequeathal to which you’ve been called to be a good steward.

Picture, for a moment, the hobo who pitches a tent on the estate of a rich landowner. A few hours later, a tap comes on the door of his tent. It’s the landowner’s security detail. “Leave me alone!” the hobo snaps. “I ain’t hurting nobody!” But the hobo has missed the point: whether or not he is hurting anybody is not the issue. The point is that he is on the landowner’s property. And thus, it is to the landowner that he is accountable.

That analogy captures something of the sense of dependence of which we speak. But it doesn’t go far enough. The issue is not merely the land on which one pitches one’s tent. The Christian perspective is more radical still: your very body, your very life, is owned by God. So when his security detail taps on your tent, you have no ground to snap back “Leave me alone!”

You are his, whether you like it or not.

How big is the Solar System?

If you haven’t seen this 7 minute movie on the scale of the universe (which was just released on September 16th) then you need to. It’s amazing. My only quibble is that they placed the edge of the Solar System at Neptune’s orbit (3.5 miles by scale from the Sun) rather than at the heliopause (which would be closer to fourteen miles by scale). But like I said, that’s a quibble. Sit back and get a sense of the scale of our cosmic backyard.

September 15, 2015

Apathy, Hostility, and Is the Atheist My Neighbor?

If you ever try to get a book published, one of the first questions a commissioning editor will ask you is “Who is your target audience?” That is, who is going to buy your book? After all, publishers don’t publish books so that they can sit on a shelf unsold.

When I wrote Is the Atheist My Neighbor? I had no expectation that it would be flying off the shelves. After all, the market appeal to the two possible audiences — Christians and atheists — is limited, and understandably so.

My primary target was Christians. But how many Christians want to read a book that charges the Christian community with a deep and ultimately indefensible prejudice against a minority group?

I suspected the answer would be: not many. But I was hopeful! (Psychologists call that the optimism bias.) And it can be said that in the last three months the handful of reviews I’ve had from Christians have all been very positive. I haven’t read a negative review yet. Even better, I’ve done multiple interviews on media ranging from podcasts to nationally syndicated radio shows. Those interviews have covered a range of diverse topics related to the book, and they’ve all been very positive.

But save that handful of reviews, the response from the Christian community has been silence.

Even more interesting, and perhaps disappointing, has been the response from the atheist community. Back in June-July I had approximately 10-12 requests for review copies of the book from various atheist bloggers and podcasters. Some of them appeared to be very excited about the book’s thesis. And yet, 2-3 months later, not a single review has appeared. Yet again, silence.

Perhaps more surprising has been the degree of hostility I’ve received from some atheists. Thankfully, this response is very much in the minority, but it is there. And it seems to express itself in two primary ways.

Dismissiveness. In this case, the attitude seems to be that the Rebellion Thesis (the thesis I critique in my book) is so patently absurd that a book like mine is merely stating opinions which are already obvious to any reasonable person. As one atheist wrote, “The rebellion theory strikes me as being without any merit. I don’t see wasting time with it.”

By analogy, it is as if you were trying to sell people on a book that argued “Science is a valuable tool for understanding the world.” Of course it is! Which rational person needs to read a book arguing for the obvious?

Ridicule. The second brand of hostility is expressed in straight up ridicule. For example, in one instance I contacted an atheist podcast to let them know about the book and offer a review copy. In their response email they declined the offer and suggested I donate a book to their town library!

In that case, I don’t know the source of the ridicule, but in other cases, it seems to be sourced in the assumption that I’m distorting the meaning of the Bible to try and make Christianity more defensible. (In the book I show how several biblical verses which are commonly invoked in favor of the Rebellion Thesis do not in fact support it.) Here is how one atheist put it:

“This is a common ploy among current Christians forced to face the fact that scriptures views are completely stupid. Just reinterpret the words to mean something they really don’t say.”

So three months on, the response has been largely apathetic punctuated with instances of dismissive or ridiculing hostility.

The silver lining, as I noted above, is that those who actually read the book seem to like it.

September 14, 2015

Still Talking Atheism on The Trinities Podcast

Part 2 of my interview on Dale Tuggy’s Trinities Podcast. To comment on the episode you can also visit the Trinities website here.

Does William Lane Craig care about the truth of Christianity?

Editor’s Note: Since this article was posted, Jeff Lowder sent me the following note via email: “I never thought that Craig doesn’t care about the truth. I was careless and sloppy when I said I agreed with Rumraket on everything except for his tally of his debates. I simply didn’t read his comment carefully, and I regret the error and slur against WLC.”

* * *

A couple days ago Jeff Lowder posted an “Open Letter to (and Standing Debate Invitation for) William Lane Craig“. I support Jeff’s bid to debate Craig. However, the point of this article is to challenge one of the commenters in the thread and Jeff’s support for his position.

It begins with the commenter, Mikkel “Rumraket” Rasmussen who opined that as regards the

“dispassionate objective search for what is actually true”, “Craig’s achievements are in fact nonexistant. If not outright negative, he’d have to crawl up to reach zero.”

Whoa, them’s fightin’ words.

After challenging Rasmussen on his comments which I found to be completely unfair, he responded with the following putative evidence that Craig is not concerned with knowing the truth:

“Craig doesn’t pursue arguments and evidence in order to discover truth, he does it to discover how best to defend christianity [sic] from disproof. He’s an apologist and an evangelist first, a philosopher 2nd. He says it himself: ‘The way that I know Christianity is true is first and foremost on the basis of the witness of the Holy Spirit in my heart. And this gives me a self-authenticating means of knowing that Christianity is true wholly apart from the evidence. And therefore if in some historically contingent circumstances the evidence that I have available to me should turn against Christianity I don’t think that that controverts the witness of the Holy Spirit.’

“Craig is an outstanding debater and wins pretty much all his debates, with a few draws among them, maybe one narrow loss in his entire career. But oustanding [sic] in his unflinching search for truth? Not so much.”

I might have ignored this except Jeff Lowder then commented by sharing his agreement with Rasmussen’s assessment of Craig’s commitment to truth:

“I agree with your entire comment, except for your tally of his win-loss-tie record.”

In reply, I have three points for Rasmussen and Jeff, keeping in mind the latter’s bid to debate Craig.

First, as Dale Carnegie observed, “A barber lathers a man before he shaves him.” Applied to this context: if you want a person to consider seriously your invitation to debate, it is unwise to go on record affirming the conviction that when that person debates, they don’t care about the truth. Speaking personally, if somebody wanted to debate me and then made that kind of public declaration about my attitude to truth, I would be disinclined to consider their invitation any further.

Second, Rasmussen’s comment appears to appeal to a classic false dichotomy: either one pursues argument to discover truth or one pursues argument to defend one’s belief. But it need not be either/or. Indeed, it rarely ever is.

Apologetics just is the act of providing grounds or evidence in support of one’s beliefs, whatever the subject matter or content of those beliefs may be. You can be an apologist for Christianity, or atheism, or your favorite sports team, or a political candidate, or an environmental policy, or a brand of clothing, or whatever. In all these cases, one is presumably an apologist for the subject matter in question because one believes the claims one is defending are true.

The glaring exception to this is the sophist, i.e. the one who plays the role of apologist not to defend what one believes to be true but rather merely to win an argument. But by no stretch of the imagination is Craig a sophist. He is deeply persuaded of the truth of Christianity. And his conviction in the truth of Christianity is manifested precisely in his spirited and meticulous defense of it.

By the same token, an atheist who was deeply persuaded of the truth of her beliefs could likewise manifest her own conviction in the truth of atheism by her spirited and meticulous defense of it.

Consequently, I find Rasmussen’s claim that “Craig doesn’t pursue arguments and evidence in order to discover truth” to be indefensible. Craig is no sophist and his intention is indeed to discover truth. Whether he does is another question, but one can hardly fault his intentions.

This brings me to my third point. Rasmussen purports to give evidence supporting his claim that “Craig doesn’t pursue arguments and evidence in order to discover truth”. That evidence consists of a quote from Craig. To recap, this is the passage that Rasmussen quotes from Craig:

“‘The way that I know Christianity is true is first and foremost on the basis of the witness of the Holy Spirit in my heart. And this gives me a self-authenticating means of knowing that Christianity is true wholly apart from the evidence. And therefore if in some historically contingent circumstances the evidence that I have available to me should turn against Christianity I don’t think that that controverts the witness of the Holy Spirit.'”

As I noted in responding to Rasmussen, I am on record critiquing Craig on his view of ultima facie justification. (See here and here.) But, as I noted as well Rasmussen’s argument is a non sequitur:

“the fact that Craig defends ultima facie justification does not support the conclusion that he doesn’t pursue arguments to discover truth.”

To illustrate why, we must be clear that Rasmussen’s objection to Craig assumes a general principle which, for lack of a better term, I’ll refer to as the Truth Principle. While Rasmussen never states the principle explicitly, he appears to assume something like this:

TP: If a person maintains that some views they have on a particular subject matter are invulnerable to evidential objections, then that person does not care about the truth of that subject matter.

Consequently, since Craig says that his core Christian convictions are invulnerable to evidential objections, it follows that he doesn’t care about the truth of those Christian convictions.

But as I said, the conclusion doesn’t follow. All this means is that Craig believes there are no arguments that are sufficient to undermine his justification in accepting Christianity.

Consider an analogy from ethics. Let’s say that Dave takes the position that it is always wrong to inflict intense pain on sentient creatures simply because one derives pleasure from doing so. Dave may readily enter into rigorous debate with ethicists who think otherwise. And he may care very deeply about the truth of his conviction. And all the while he may take the view that his convictions in the truth of his position are so powerful that even if he cannot answer the objections of his interlocutors, he would still maintain that it is always wrong to inflict intense pain on sentient creatures simply because one derives pleasure from doing so.

Let’s consider another example. Shelly is deeply persuaded of the existence of herself as an acting subject that exists through time. At the same time, she engages in debates with bundle theorists who deny that there is any reified self which exists through time as a subject. She cares deeply about the truth of her position even as she holds that there is no objection to the self that could be strong enough to shake her conviction.

Examples could readily be multiplied, but this should suffice to demonstrate that TP is false.

To sum up, as I said, I don’t agree with Craig’s position on the ultima facie justification of Christian belief. And I can see how stating his views could, in certain contexts, be counter productive to dialogue and debate. For example, it would make little sense for Craig to declare that nothing will change his mind as a preface to a debate. Such a move would merely encourage retrenchment on both sides.

But it is equally counterproductive to claim that Craig doesn’t care about truth simply because he is of the conviction that no objections could be sufficient to dislodge his religious convictions.

September 12, 2015

Can Christians and Atheists Stop Fighting? The Rauser/Shaha Conversation

It’s hard to believe, but this is my fourth appearance on “Unbelievable” with Justin Brierley. In this episode we set aside the standard debate format for a more collegial discussion based on my book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? Rethinking Christian Attitudes Toward Atheism. My partner in the conversation was Alom Shaha, author of the popular book The Young Atheist’s Handbook. You can listen to the show and join the conversation here.