Randal Rauser's Blog, page 117

September 2, 2017

What is the Trinity? A Review

Dale Tuggy. What is the Trinity? Thinking About the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. CreateSpace, 2017, 142 pp.

Dale Tuggy. What is the Trinity? Thinking About the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. CreateSpace, 2017, 142 pp.

In one of his comedy sketches, Jim Gaffigan recalls an occasion when his young son said: “Look daddy! A silver stick!” Gaffigan replied, “Actually son, that’s an antenna!” Puzzled, the boy replied: “What’s an antenna?” After a moment, Gaffigan replied sheepishly, “It’s a silver stick.”

The Trinity is to the average Christian as an antenna is to Jim Gaffigan: we know just what we mean … until we’re asked to explain it. And that’s why the simple question at the heart of Dale Tuggy’s new book is so challenging.

If there is anyone well suited to ask some probing questions on the doctrine of the Trinity, it’s Dale Tuggy. A professional philosopher, Dale has been thinking hard about this doctrine for twenty years, much of it through a range of popular and academic articles as well as his prodigious blogging and podcasting at his Trinities blog. I’ve long been a fan of Dale’s clear writing, pedagogical skill, and dry wit. So when I learned that he had added his new book What is the Trinity? to that growing library of resources, I knew I had to get a copy.

Dale’s Theology

One thing you should know at the outset: Dale does not accept the church’s doctrine of the Trinity. Indeed, Dale is a unitarian. (While he saves that revelation for late in the book (p. 132), it would be hard to miss the hints prior to that point.) For Dale, that means that there is one absolute God, the Father, while the Son and Spirit are lesser beings not equal to the Father.

One thing you should know at the outset: Dale does not accept the church’s doctrine of the Trinity. Indeed, Dale is a unitarian. (While he saves that revelation for late in the book (p. 132), it would be hard to miss the hints prior to that point.) For Dale, that means that there is one absolute God, the Father, while the Son and Spirit are lesser beings not equal to the Father.

Now you might be wondering: why read a unitarian about the Trinity? Fair question. First, we should note that while Dale is presently a unitarian, he started his inquiry twenty years ago as a committed evangelical trinitarian. Indeed, at the time he was convinced that “Only dastardly pseudo-Christian cults denied it.” (1) Dale will insist that he was persuaded to adopt unitarianism by the weight of evidence. And in the spirit of iron sharpening iron, I find it a healthy exercise in critical thinking to engage with dissenting perspectives.

Dale embodies the philosophy of the Bereans (a biblical allusion to which he appeals more than once). Just as the Bereans kept an open mind to what Paul had to say, so we should keep an open mind to Dale. Having said that, What is the Trinity? is not an apologetic for Dale’s particular views: rather, it is an invitation to the general reader to undertake their own journey of theological reflection and clarification.

Ten Chapters: An Overview

Sadly, many will be resistant to begin this journey out of fear that they will be led into error as a result, an error that could lead to the loss of their very salvation. I know that worry myself (and I talk about it at some length in What’s So Confusing About Grace?).

But before we worry about getting our doctrines wrong we need to clarify just what trinitarian doctrine is in the first place. And that is by no means clear, a point that Dale brilliantly illumines with the following scenario:

Imagine meeting a new neighbor who introduces you to the two women at his side.

“Hi neighbor! This is my wife Alice. We’ve been married for exactly five years.”

“Pleased to meet you.”

“And this is my wife Betty,” he says, pointing to the other woman. “We’ve been married exactly three years.”

“I’m pleased to meet you and your two wives,” you reply. “I’ve never met anyone who was married to two women.”

“Oh no, neighbor, we don’t say ‘two wives’ or ‘two women.’ In truth, I’m married to just one woman; I have just one wife. True, Alice is one person, and Betty is another; but we neither confuse the persons nor divide the wifehood.” (pp. 9-10)

Just as it is by no means clear what this man even means when he insists that his two spouses constitute a single wife, so it is by no means clear what it would even mean to say that three distinct, divine persons just are one God. Surely we can at least seek to clarify what it is we Christians are supposed to believe before we worry about the repercussions of doubting it?

Furthermore, it is worth asking whether God would really damn people for drawing errant conclusions from a study that was undertaken in a good faith pursuit of the truth. So long as we conclude that it couldn’t possibly be so, we only need to concern ourselves with the question of whether we reason in good faith to begin with.

Many others will be resistant to undertaking this inquiry not out of fear but rather out of the belief that we already have all the answers we need: there is one God who exists as three persons. However, in chapter 2 Dale points out that this basic formula is open to many interpretations. And that presses us to consider which interpretation we believe to be correct.

We begin this critical journey in chapter 3 by distinguishing between the biblical revelation of the trinity (that is, Father, Son, and Spirit as three actors in the divine economy) and the church’s later interpretation of these three as comprising one God (i.e. the Trinity).

As Dale sees it, in the early church Christians regularly referred to the Father as “God” in an absolute sense. However this began to change as early as 385 when Gregory of Nyssa referred to the Trinity as God (p. 44). This shift was later ratified by the great theologian Augustine.

The doctrine of the Trinity asserts that God is one divine substance in three persons. But what do we mean by “person”? Dale devotes chapter 6 to this question. Social trinitarians veer toward tritheism by interpreting the divine persons in the Trinity as analogous to human persons in community.

Since Augustine, many other Christians have sought to guard against tritheism by retreating to highly apophatic treatments of person (see Karl Barth and Karl Rahner as modern examples). But as Dale observes, there is something deeply unsatisfying about this retreat to a via negativa: “Can this be the great discovery of Christian theology – that within the one God there are three ‘somewhats,’ three something-or-others?” (p. 62)

I found myself in the middle of this very debate eighteen years ago when I got in an impromptu debate with my Doktorvater Colin Gunton. At the time I insisted, with a nod to Thomas Nagel’s famous criterion for consciousness, that we could minimally assert there is something it is like to be the Father, there is something it is like to be the Son, and there is something it is like to be the Spirit. I concluded that in this sense at least, we could speak of three centers of consciousness — or three minds — in the Trinity. To my surprise, Gunton, a committed Barthian, was resolute in his opposition to this point, a point which I took to be trivially true.

In chapter 7 Dale turns from three persons to the one substance (or ousia). This yields the best chapter title in the book: “‘Substance’ Abuse?” It also yields the most heady chapter as Dale subjects the reader to nine possible interpretations of substance, noting the strengths and weaknesses with each. While I suspect this will be a tough slog for the layperson, for those who endure it provides a very helpful conceptual framework for sorting through the confusion.

By this time it will be clear that defining “antenna” is mere child’s play when compared to the Trinity. But then perhaps that’s the way it is supposed to be. After all, isn’t the Trinity supposed to be a “mystery”? Dale addresses the retreat to mystery in chapter 8.

I know the mystery card well: every year when I teach systematic theology I have students who attempt to preempt theological reflection on the Trinity by playing this card. But Dale cleverly turns this alleged appeal to epistemic humility on its head:

“From our own theoretical failure, we should be hesitant to infer that no living person could do better. This is to suppose that we are more competent and/or better informed and/or more diligent than all others. Are we really all that?” (p. 96)

In short, while one may end in mystery, one should not allow an appeal to mystery to preempt a legitimate inquiry.

Dale also provides a helpful grid for thinking about the topography of appeals to mystery with his illustration of so-called “Mystery Mountain” (pp. 108 ff.). To sum up, when it comes to any set of contradictory or contrary claims, there are four possibilities: (1) agnosticism (failing to affirm either P or not-P); (2) affirming P; (3) affirming not-P; (4) affirming P and not-P.

Only (4) truly puts us on the peak of Mystery Mountain. And as Dale observes it is nearly impossible to stay there: almost inevitably, the proponent of mystery slips surreptitiously back to one of the other positions. Karl Rahner famously observed that most Christians are “mere monotheists”. Look closer, and I suspect that for all intents and purposes, many others are functional tritheists. Suffice it to say, few Christians truly remain atop Mystery Mountain for long.

The book concludes with a couple chapters discussing use of the term “God” and summarizing the resulting disagreement that exists among Christians. Dale then concludes with an epilogue in which he offers the proper response to the debates surveyed throughout the book: “The serious truth-seeker” he opines, “runs towards such disagreements, not away from them. “(p. 140)

Critical Footnotes

At this point, I’d like to offer three points of modest critical engagement with What is the Trinity?

To begin with, I’d like to address Dale’s read of history. Dale believes the triadic formulas embraced by the early church which limit supreme deity to the Father are to be preferred to the later trinitarian formulas that are codified beginning at Constantinople (381). Notably Emperor Theodosius is viewed in a negative light as one who “forcibly installed [pro-Nicene] Gregory of Nazianzus as bishop” and then “assembled a meeting of 150 eastern bishops to, as one historian says, ‘ratify the new order.'” (p. 56)

To be sure, Dale is free to disavow this intrusion of politics into theological formulation as a corrupting influence. But then, why stop there? The fact is that politics and power have played a role in theological formulation since the earliest years of the church. So why not adopt Bart Ehrman’s project of attempting to retrieve other Lost Christianities which were stamped out during the pre-Nicene centuries? Conversely, if one concedes that the divine voice could come through the use of politics and power at an earlier period, why not in the late fourth century as well?

My second concern is that Dale’s method seems at times to be rather individualistic and rationalistic. Consider the point where Dale writes:

no Christian should ever adopt a theology because some supposedly Christian scholar told her so. You must read the sources for yourself, with mind and spirit open. You must ask the one God to clarify his revelation to you, and you must be patient through a process that will probably take you many months, if not many years. (p. 133)

On the one hand, I’m sympathetic with this advice. As Immanuel Kant proclaimed, “Sapere aude! Dare to know!” In other words, we should have the courage and motivation to seek to understand matters for ourselves.

Having said that, there are important limits to this advice. I go through life believing things because trusted authorities told me so. And that kind of deference to authority is fully rational and indeed necessary. So I trust my medical doctor, I trust my meteorologist, I trust my architect, and so on. When it comes to matters of doctrine, isn’t there also a place to trust the theologian and historian, the priest and pastor?

What is more, the matter is not merely what “some supposedly Christian scholar” says, but what an ancient and venerable tradition says. To be sure, I’m not saying one must simply accede to ancient and venerable traditions because they’re old and venerable: “Ecclesia semper reformanda est!” Rather, the issue is a matter of balance. There is a time to seek to critique our beliefs and traditions, but there is also a time to yield to them. And I see nothing wrong with a Christian deferring to the wisdom of a tradition on such a central matter, even when many problems undoubtedly remain.

Finally, I’d like to return to the looming question of orthodoxy. However, rather than focus on Dale’s unitarianism, I’d like to discuss instead another “minority report”: modalism. Throughout the history of the church, there have been professing Christians who adopt a modalistic interpretation of the Trinity. The most significant expression of modalism today is the Oneness Pentecostal movement.

While I thought Dale might show some sympathy for the modalist as a fellow traveler outside the orthodox norm, he instead insists that this interpretation “should be unacceptable to any Christian. The New Testament clearly assumes and implies that there have been and indeed are differences between the Father and the Son.” (pp. 78-9) Later, when discussing the Creed of Nicaea’s claim that the Father and Son are the same ousia (substance) Dale observes, “Theologians point out that this would leave heretical ‘modalism’ as an option.” (p. 98)

I note that Dale doesn’t disavow the description of modalism as heretical. This leads me to wonder how Dale draws the lines of orthodoxy and heresy and why.

What about you?

While Dale’s theology is interesting, this book ultimately isn’t about Dale’s views. Rather, it is about your views. How will you think about the trinity revealed in the New Testament? Will you accept the church’s doctrine of the Trinity? And how will you define key terms like person, substance, and God?

These questions are daunting. But if you’re tired of camping on Mystery Mountain, if you are ready to run toward disagreements in your pursuit of understanding, then What is the Trinity? is an indispensable guide for the journey.

Order your own copy of What is the Trinity? here.

The post What is the Trinity? A Review appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 31, 2017

Ashamed of Jesus? Go to hell

Have you ever been ashamed of Jesus? Have you ever worried that being ashamed of Jesus might lead to your eternal damnation? I know what that’s like. Read my new article at confusedaboutgrace.com.

The post Ashamed of Jesus? Go to hell appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Two New Reviews for What’s So Confusing About Grace?

The first review was posted by David Haitel at Amazon.ca. David writes: “I appreciate Dr. Rauser’s readable and conversational style as well as his strong affirmation of the truth of God’s Word. He clearly outlines the beauty, simplicity, and richness of God’s grace. Christ’s love is truly at the center of His grace. Excellent and encouraging read!”

The second review was posted by Geoff Ball at Amazon.com. Geoff writes: “What I love most about this book is that Randal speaks honestly, from the heart, like a close friend articulately sharing his innermost thoughts over a coffee (or a beer). I highly recommend this book to anyone who is confused about God, salvation, Jesus, heaven, the bible, and of course one of the most mysterious topics of all: Grace.”

Thanks David and Geoff.

The post Two New Reviews for What’s So Confusing About Grace? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 30, 2017

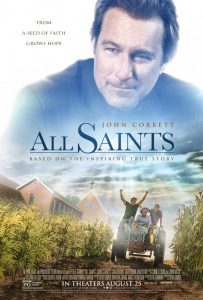

All Saints: A Christian movie for non-fundamentalists

A few weeks ago I was invited to attend a pre-screening of All Saints, a “Christian movie”. I’m not sure what a Christian movie is, but as best I can guess, in popular parlance it is a movie marketed to evangelical Christians.

A few weeks ago I was invited to attend a pre-screening of All Saints, a “Christian movie”. I’m not sure what a Christian movie is, but as best I can guess, in popular parlance it is a movie marketed to evangelical Christians.

That in itself is enough to make me skeptical. As a cinephile, I’m interested in good movies. As a Christian, I’m interested in morally significant movies. If you want to see the confluence of these interests watch a movie like Short Term 12. (See my article “Finding Jesus at the movies, but not in Jesus movies.”)

Needless to say, movies that are distinguished primarily by their appeal to evangelical Christians offer little guarantee of either quality or moral significance. As a result, I came to the screening of All Saints predisposed not to like it. In case you’re inclined to judge me, keep in mind that I’ve seen both God’s not Dead and God’s not Dead 2, so I have reason to be skeptical.

So I was more than a bit surprised to find that All Saints won me over. To be sure, I’m not claiming it’s a work of art. But it was reasonably good and it was indeed morally significant.

The film is based on a true story and features John Corbett, one of the most eminently likeable actors working today, as an Episcopalian priest assigned to a dying church with the express intent of closing said church within a few months. Instead, the church ends up embracing a marginalized population of immigrants (a sadly subversive message in the age of “build the wall!”).

Together the church and its new membership of immigrants decide to try their hand at farming, raising crops in pursuit of sustainability. By the end of the film we are treated to an abundant harvest, but not the one we expected. (How’s that for walking the razor sharp line of the spoiler alert?)

All Saints presents a powerful message of social justice love and inclusion bereft of the heavy-handed repentance/conversion narratives and culture war themes of your typical evangelical Christian films. Indeed, the film portrays Buddhists and nones in a positive light as they rally to the aid of the fledgling congregation. Within this cinematic context, that’s practically revolutionary.

And to top it all off, St. Thomas Church, the New York Episcopalian church immortalized in Burton Cummings’ song “I’m Scared,” even gets a mention.

So here’s the bottom line: by the time the credits rolled, I was a convert. All Saints is not going to win an Oscar, and it wasn’t even in contention for the Palm d’Or at Cannes. But if you value movies that are (reasonably) good and/or morally significant, I’d say this film has earned your theater-going dollar.

The post All Saints: A Christian movie for non-fundamentalists appeared first on Randal Rauser.

The “Nashville Statement”: Three Problems with the Preamble

Yesterday the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood issued “The Nashville Statement“. I’m sympathetic with many concerns of The Nashville Statement and I believe many of the statements in the document are well-crafted and fundamentally correct.

Unfortunately, I also have significant concerns with the document and they start at the beginning. In this article I’m going to raise three concerns in response to some excerpts from the Preamble:

As Western culture has become increasingly post-Christian, it has embarked upon a massive revision of what it means to be a human being.

It is common to think that human identity as male and female is not part of God’s beautiful plan, but is, rather, an expression of an individual’s autonomous preferences.

Will the church of the Lord Jesus Christ lose her biblical conviction, clarity, and courage, and blend into the spirit of the age? Or will she hold fast to the word of life, draw courage from Jesus, and unashamedly proclaim his way as the way of life? Will she maintain her clear, counter-cultural witness to a world that seems bent on ruin?

So what are my concerns with the Preamble based on these excerpts?

First, it fails to distinguish between sex (a genetic and physiological reality) and gender (a socially constructed role). But these are very different (albeit related) topics. Consider: is it part of “God’s beautiful plan” that boys wear blue and girls wear pink? Did God plan for boys to play with toy cars and girls with toy dolls? Are boys supposed to grow up to be policemen and firemen while girls grow up to be secretaries and homemakers?

The last I checked, no Christian creed or statement of belief addressed these topics. And so it seems to me that it is perfectly reasonable for Christians to question various aspects of the social formation of gender roles. Consider one concrete example: if a boy says he wants to wear pink, are his parents capitulating to a “massive revision of what it means to be a human being” by acceding to his request? Perhaps, but it sure ain’t obvious that it’s so.

Second, note in particular how the Preamble associates the “massive revision” with the individual’s voluntaristic will. To be sure, there are some people who conform to that description, most perspicuously those who define themselves as “pansexual”. (E.g. many self-described pansexuals see their own will as determinative of their sex and gender expression at any given moment.)

But many other people (e.g. many gays and transgenders) insist that their sex and/or gender expression is not a matter of their will. On the contrary, from the youngest age they have always experienced a seemingly unalterable attraction to the same gender (or, in the case of a transgender person, a dysphoria with their birth sex).

The case is even more striking with intersex people who exist on a spectrum (genetic and/or physiological) between male and female. Intersex people have a congenital condition according to which they do not conform to “God’s beautiful plan” of being male or female: this condition has nothing to do with the will.

(The document does allude to intersex people; I’ll return to that in a later part of my review of this document. For now, we can just note that their condition is not a matter of the will.)

Consequently, one fails to grapple with the unique ethical and social issues faced by many people in the LGBTQIA community when one attempts to reduce all individuals within this broad coalition to a matter of voluntaristic will.

Third, the Preamble presents the signers of The Nashville Statement as being on the side of the angels in opposition to the “massive revision” of a “world that seems bent on ruin”. As they soberly ask,

“Will the church of the Lord Jesus Christ lose her biblical conviction, clarity, and courage, and blend into the spirit of the age?”

That’s a great question. But before we turn to consider various outgroups, we might begin closer to home.

Let’s consider, for example, the case of individuals who divorce and remarry for any reason other than porneia, an act that Jesus explicitly denounced as tantamount to adultery. Given that standard, the pews of evangelical churches are full of couples that are engaged in adulterous relationships.

As The Nashville Statement speaks boldly against “the spirit of the age,” it’s silence on this topic is nothing short of deafening. Needless to say, the Statement would be far more credible on the issue of “biblical conviction, clarity, and courage,” if it had addressed the problem of divorce and remarriage.

The post The “Nashville Statement”: Three Problems with the Preamble appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 29, 2017

The latest review of What’s So Confusing About Grace?

Here’s another review of What’s So Confusing About Grace? at Amazon.com. This one comes courtesy of Daniel Rieder.

Thanks, Dan!

The post The latest review of What’s So Confusing About Grace? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

“I am going to bring floodwaters on the earth…” Could God be punishing Texas?

13 So God said to Noah, “I am going to put an end to all people, for the earth is filled with violence because of them. I am surely going to destroy both them and the earth. […] 17 I am going to bring floodwaters on the earth to destroy all life under the heavens, every creature that has the breath of life in it. Everything on earth will perish. (Genesis 6:13, 17)

“I know for a fact this is the worst flood Houston has ever experienced.” (Patrick Blood, Weather Service meteorologist)

A photo of the residents of the La Vita Bella Nursing Home in Dickinson, TX in their flooded facility awaiting rescue.

Did God literally flood the earth as a form of punitive judgment on a sinful humanity? And if so, could he do it again? Could he be doing it right now in particular regions of the earth? Regions like Houston and southeast Texas?

As you can probably guess, the suggestion that God might be punishing Houston and southeast Texas by way of a hurricane-induced flood will be met with universal incredulity (to say the least). Many Christians will insist not only that God is not punishing Texas via a flood but that God would not do such a thing.

There are at least three considerations which strongly support that categorical judgment.

To begin with, flood-punishment is indiscriminate. It doesn’t select between the culpable and the innocent — or the more culpable and less culpable. Instead, it destroys both the homes and lives of the good and evil (or culpable and less culpable).

According to one report, four children and their great-grandparents drowned when their van plunged into a raging torrent while trying to escape the flood. But the children’s great uncle escaped. Should we conclude that the children (including a six year old) and their great-grandparents were justly drowned as punishment for some actions while the great uncle was properly spared?

In short, the devastation and suffering resulting from this kind of natural disaster appears arbitrary and indiscriminate. That is the first reason people are rightly skeptical that it should be interpreted as punishment.

Second, natural disasters like the Texas flood lack an interpretive context. Imagine, for example, that Billy steals a cookie from the cookie jar. His parents observe his deceptive action but they say nothing. Then, six months later, Billy’s parents tell him he cannot watch any television or play video games for the day. The punishment is a response to Billy’s deception six months earlier, but Billy’s parents never tell him their actions are punishment for his deception. Note that even if the punishment is a proportional response to the indiscretion, nonetheless it would be wrong for Billy’s parents to punish him without explaining what the punishment was for. Proper punishment (whether punitive or reformational) requires the one being punished understand the link between indiscretion and punishment.

Needless to say, there is no voice from heaven instructing all the people of Texas that they are being punished for some particular set of indiscretions. Consequently, the lack of interpretive context to explain the punishment to the ones being punished supports the conclusion that this flood is not, in fact, punishment.

Finally, if the flooding in Texas were punishment it would certainly qualify as cruel and unusual. From elderly people slumped over in their wheelchairs, waist-deep in fetid, sewage-laced water to terrified children being pulled under a raging current, the suffering produced by the floods in Texas are horrific and simply not explicable as a proper form of punishment for any crimes.

As I write, the official death toll resulting from Hurricane Harvey sits at 3, but as the reports roll in (including that of the four children and their grandparents), it is tragically clear that many more will suffer the ultimate loss from this flood: the deprivation of their own lives by way of drowning.

A decade ago at the height of the controversy over water-boarding as a means of interrogation, Christopher Hitchens submitted himself to be water-boarded — a process that simulates drowning — to see if it really qualifies as cruel and unusual punishment. The memorable title of the article he wrote, “Believe me, It’s Torture,” tells you his conclusion. Nonetheless, it is worth quoting his account at some length:

“In this pregnant darkness, head downward, I waited for a while until I abruptly felt a slow cascade of water going up my nose. Determined to resist if only for the honor of my navy ancestors who had so often been in peril on the sea, I held my breath for a while and then had to exhale and—as you might expect—inhale in turn. The inhalation brought the damp cloths tight against my nostrils, as if a huge, wet paw had been suddenly and annihilatingly clamped over my face. Unable to determine whether I was breathing in or out, and flooded more with sheer panic than with mere water, I triggered the pre-arranged signal and felt the unbelievable relief of being pulled upright and having the soaking and stifling layers pulled off me. I find I don’t want to tell you how little time I lasted.”

Now, if you dare, try to imagine the experience of four small children and their great-grandparents being pulled under those swift-moving floodwaters. Surely, the reasoning goes, no good and just God would exercise punishment of his creatures in this manner.

Consequently, we have three excellent reasons to believe not only that God is not punishing Texas by way of flood, but more strongly that God would not punish diverse populations in geographic regions by way of floods.

Of course, that conclusion now gives rise to a tension with the biblical narrative. Now as the reader turns to biblical accounts of divine punishment through natural disaster such as we find in Genesis 6, one must choose: either,

(1) find a way to reread the narrative according to which God did not literally at some point in the past punish a diverse population in a particular geographic region by way of a flood;

or

(2) accept that it is at least in principle possible that God is punishing Texas by way of a flood.

The post “I am going to bring floodwaters on the earth…” Could God be punishing Texas? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 27, 2017

On Keeping a Closed Mind: Lessons from The Friendly Atheist

A couple days ago The Friendly Atheist posted an article titled “Christian Textbook Urges Readers To ‘Keep a Closed Mind’.” The short article features a screenshot from a page out of a textbook for Christian young people. (Before this I’d never heard of the book, What’s on Your Mind? Discover the Power of Biblical Thinking, or the author Baptist John Goetsch, or the publisher Striving Together Publications.)

The screenshot is the first page of chapter 8 and is provocatively titled “The Closed Mind.” The “Lesson Aim” of the chapter is “to close our minds to unrighteous thoughts as they come through various diversions, demands, and deceptions.”

Mehta retorts,

“Wouldn’t it be better advice to counter false teachings with strong rebuttals instead of avoiding them altogether?

“You don’t defeat an argument by running away from it.”

It should be no surprise that I agree with Mehta here. After all, I defended atheism in a public radio debate and I wrote a book defending atheists from the charge that they are in rebellion against God.

But here’s the key: keeping an open mind obliges one to steelman one’s opponent. Conversely, keeping a closed mind involves strawmanning one’s opponent.

And that includes Baptists like John Goetsch.

So what would it mean to steelman Goetsch’s chapter? For starters, one might try reading the chapter rather than only mocking it based on the first page.

Barring that, we can simply return to the lesson aim and see if it is possible to adopt a charitable reading. To recap, the aim of the chapter is:

“to close our minds to unrighteous thoughts as they come through various diversions, demands, and deceptions.”

Let me note here that there are at least two possible ways to interpret the aim of having a “closed-mind”:

(1) Goetsch is encouraging the reader to refuse to engage critically in alternative perspectives.

(2) Goetsch is encouraging the reader to adopt a heightened skepticism about particular alternative perspectives.

Mehta adopts the first reading. As he puts it, “forcing people to just stick their fingers in their ears at the first sign of opposition is a horrible way to convince them your ideas are right.”

But the evidence provided — a screenshot of the first page containing a Bible verse, a lesson summary, and a lesson aim — underdetermines that interpretation.

This is unfortunate since the second reading is far more charitable. And steelmanning begins with charity. It could be that Goetsch is just encouraging people to “stick their fingers in their ears.” But I suspect the reality is rather more nuanced.

I wouldn’t say Mehta necessarily strawmanned this book. But he made no effort to understand it charitably. Instead he chose to serve up yet another item of mockery for his enthusiastic readership so they could exult in their intellectual superiority over the poor, benighted fundamentalist Christian. (Just read the dozens of comments beneath the article.)

Mehta concludes his short article with a wry allusion to intellectual bubbles:

“What’s the next chapter in this book? How to keep the inside of your bubble clean?”

One might ask the same question of The Friendly Atheist.

The post On Keeping a Closed Mind: Lessons from The Friendly Atheist appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 25, 2017

Is it technically morally wrong to proselytize for something other than the true religion?

I encountered the question this morning in a tweet from Counter Apologist:

Question for Theists:

Is it technically morally wrong to proselytize for something other than the true religion?

— Counter Apologist (@CounterApologis) August 25, 2017

Point One

In response, the first point I made is that proselytization is simply the act of attempting to persuade others to hold a particular set of beliefs that you, yourself hold. (I am going to assume, for the sake of simplicity, that one accepts the doctrines in question as true though it is certainly possible to proselytize for beliefs one does not accept.)

With that in mind, we can reword the question with respect to proselytization generally as follows:

Is it technically morally wrong to proselytize for something other than true beliefs?

Now let’s consider an example. Dave and Lee have very different ideas of how the municipal government should address urban gridlock in Los Angeles. Dave believes the government should fund an expansion of mass transit while Lee believes that the government should fund a city-run bicycle loan system. Dave and Lee both present their ideas at a meeting at city hall. Some years later it becomes clear that Dave was correct and Lee was incorrect. Does it thereby follow that Lee behaved in an immoral fashion whereas Dave did not?

Of course not. The lesson is that the truth of one’s beliefs is not connected to the moral assessment of the act of proselytizing for those beliefs.

Point Two

This brings me to the second point. It is still possible that Lee behaved in an immoral fashion. For example, it could be that the evidence for the superiority of Dave’s mass transit view was so overwhelming that Lee could only retain his commitment to the bicycle loan system by way of an irrational intransigence toward the available evidence.

In that case, Lee could be morally culpable. But note that Lee wouldn’t be morally culpable for proselytizing for false beliefs. Rather, he would be culpable for failing to consider the evidence that contradicted those beliefs.

Christianity and Naturalism

With that in mind, let’s consider for a moment that Christianity is true and naturalism is false. In that case, the naturalist is not culpable for proselytizing on behalf of their (false) naturalistic beliefs. But even so, they could still be culpable for failing to consider the evidence that contradicted those beliefs.

The post Is it technically morally wrong to proselytize for something other than the true religion? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 23, 2017

Evangelicalism, Academic Freedom, and Robert Gagnon

Today I read an article at the Unfundamentalist Christians blog about the departure of anti-gay firebrand Robert Gagnon from his position at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary (PTS). In the article, “Gagnon out at PC(USA) Seminary” the author Don Burrows talks about Gagnon’s limited job prospects after PTS:

“Gagnon himself appears to realize [his limited prospects], as, in the announcement of his resignation, he pines for employment at an evangelical institution, noting (correctly) that ‘it seems unlikely, given my stances on sexual ethics and Scripture, that any university religion department or mainline denominational seminary would take me.’

Burrows continues:

“his scholarship falls far outside of mainstream consensus in a variety of fields. Gagnon knows this, which is why he states that God is calling him to an evangelical institution. By ‘evangelical,’ I think Gagnon means those institutions that do not generally pay heed to peer-reviewed scholarship in academia at large, but instead hew to a specific set of ideologies and require their faculty to play within that limited sandbox.”

Personally, I found Gagnon to be unpalatable. In the comments I wrote: ” While I never met him, I have heard him on many occasions and he always struck me as combative, acerbic, and condescending. I can’t imagine what it would be like to share the same photocopier. I suspect things may have gone differently for him if he’d shown more of a gentle, Christlike spirit … and ditched the bow ties.” (For more on my perspective see my review of Gagnon’s debate with Jayne Ozanne on “Unbelievable.”)

But the real bee in my bonnet concerned Burrows’ withering comments about evangelical institutions, their alleged “ideologies” and the resulting “limited sandboxes”. In response to those points I replied to Burrows as follows:

“You paint with a very broad brush here. I don’t dispute that the work of scholars employed by avowedly evangelical institutions is constrained by “a specific set of ideologies” which leads to a “limited sandbox.” But as your post illustrates, that is likewise true of a mainline PCUSA seminary: whatever else you think of it, Gagnon’s scholarship did not conform to the ideological expectations at Pittsburgh. It is also true of secular institutions. (I remember, for example, Norman Finkelstein’s infamous and ultimately futile attempt to secure tenure at DePaul.)”

The post Evangelicalism, Academic Freedom, and Robert Gagnon appeared first on Randal Rauser.