Randal Rauser's Blog, page 115

September 28, 2017

Alvin Plantinga’s Surprisingly Deflationary Take on his own Ontological Argument

Alvin Plantinga (Image Credit)

Living legend Alvin Plantinga was recently a guest on Unbelievable with Justin Brierley. The show was classic Plantinga — clear analysis, dry wit, admirable humility — and surveyed some of the highlights of his impressive career including warrant, proper basicality and Christian belief, the evolutionary argument against naturalism, and the ontological argument.

The last choice was a bit of a surprise. To be sure, Plantinga is among the most important of contemporary voices in revitalizing the ontological argument (along with Charles Hartshorne and Norman Malcolm, among others). And his treatment of the topic in The Nature of Necessity remains a model of careful, analytic modal reasoning.

That said, the ontological argument has always been something of a philosopher’s plaything — an apparatus on which to exercise one’s modal muscles and analytic intuitions. Personally, I would have preferred hearing more of Plantinga’s thoughts on science and Christian belief, an area to which he has devoted significant attention in recent years.

Nonetheless, Plantinga’s discussion of the ontological argument was intriguing, if somewhat deflationary. Brierley shared some questions inquiring into whether Plantinga viewed the argument as a proof or whether, as he had once said, it showed belief in God to be rational. Plantinga replied:

“I don’t think it proves the existence of God.”

That in and of itself is hardly surprising. In the 1990 Preface to God and Other Minds Plantinga points out that few if any arguments in philosophy might be counted proofs (i.e. a valid argument with such intuitively luminous premises that it can only be denied on pain of irrationality). So it is no objection to Plantinga’s modal ontological argument that it isn’t a proof.

The more interesting bit came shortly thereafter. Plantinga continued:

“I don’t propose it as a really strong argument.”

Plantinga doesn’t say what a “really strong argument” should look like, but I’m guessing that in addition to validity, he’s thinking it would also include the ability to persuade somebody of the conclusion who is not already inclined at the outset to accept that conclusion. (George Mavrodes once wrote an essay titled “On the Very Strongest Arguments” which provides an intriguing survey of ways one might think of success in terms of arguments and the fabled “proofs”.)

So if the argument is not really strong, what good is it? Plantinga then said this:

“It’s more like part of the logical geography of God and divinity.”

I find myself in agreement with this statement. Just the other day I was lecturing on the traditional theistic proofs and I said something very similar of the ontological argument. As I see it, the argument shows either that God exists of necessity or God cannot possibly exist. The challenge is that we seem to have conflicting intuitions. On the one hand, it seems possible that God exists (from which it follows he must exist). On the other hand, we have intuitions that it is possible that God not exist (from which it follows that he cannot exist).

So the ontological argument may not be “really strong” insofar as it would show us that God does exist. But it is nonetheless useful in laying out the “logical geography” of God’s existing.

Finally, what about Plantinga’s claim so many years ago that the ontological argument makes belief in God rational? Plantinga 2017 replies:

“That’s a claim that I did make, but I’m not so sure that it shows even that.”

To clarify, Plantinga believes Christian and theistic belief can be rational. The burdens of his argument for proper basicality and warranted Christian belief are intended to show that. But he is right to note that the rationality of Christian belief cannot rest on this argument. There are at least two reasons for this.

First, at most the ontological argument would support belief in the conditional that if it is possible that God exists then God must exist. But it wouldn’t obviously support belief in the premise that it is possible that God exists (that would seem to depend on one’s intuitions).

Second, and perhaps more importantly, this argument would at most support rationality for a small cadre of philosophers and other thinkers who have contemplated the argument (and perhaps for a smattering of others who might believe based on their testimonial authority). But it would leave untouched the rational status for the unwashed masses of theists who are unfamiliar with the argument or the defenders of it.

On September 24th Plantinga received the Templeton Prize (£1.1 million!) for his contributions to philosophy of religion. While the prize is well deserved, I can’t help but end with this charmingly deflationary assessment of his own signature ontological argument:

“It really doesn’t seem to me the argument shows much at all. It’s not one of the more powerful arguments…”

The post Alvin Plantinga’s Surprisingly Deflationary Take on his own Ontological Argument appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 26, 2017

The Provincial Atheist

The term provincialism refers to the unsophisticated individual who confuses their regional perspective (i.e. from the provinces) with a global or universal perspective. As a case in point, consider this passage from A.C. Grayling:

tell an average intelligent adult hitherto free of religious brainwashing that somewhere, invisibly, there is a being somewhat like us, with desires, interests, purposes, memories, and emotions of anger, love, vengefulness, and jealousy, yet with the negation of such other of our failings as morality, weakness, corporeality, visibility, limited knowledge and insight…. Nobody would buy such a picture if they were not indoctrinated into it. (“Can an Atheist Be a Fundamentalist?” in Christopher Hitchens, ed. The Portable Atheist, 474-75.)

The funny thing is that such beliefs in a deity appear natural to the vast majority of the world’s population. And that in turn begs the question: if the apparent naturalness of these beliefs are the result of “indoctrination,” as Grayling supposes, then how did that indoctrination become so pervasive over the world’s population in the first place?

That’s a real problem for Grayling’s position. Fortunately, there is another interpretation of the data. According to this interpretation, Grayling has different intuitions and a different plausibility framework than the majority of the world’s population. And he has facilely assumed that his intuitions and plausibility framework represent the universal norm while any deviation from it must be the result of “indoctrination.”

It seems to me that the latter interpretation is the far more plausible one. And so from my perspective, it seems that Grayling, who appears to style himself here as an enlightened, urbane individual, in fact demonstrates a surprising degree of uncritical provincialism.

The post The Provincial Atheist appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 25, 2017

A “Confusing” Dialogue with Dale Tuggy … and more

I’m delighted to be a guest once again on one of my favorite podcasts, Dale Tuggy’s Trinities. It was a fun and wide-ranging discussion about my new book What’s So Confusing About Grace? You can listen to the episode here.

And here’s the latest review of What’s So Confusing About Grace? by David Leal where he refers to it as ” a wonderful, hopeful book.”

The post A “Confusing” Dialogue with Dale Tuggy … and more appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 24, 2017

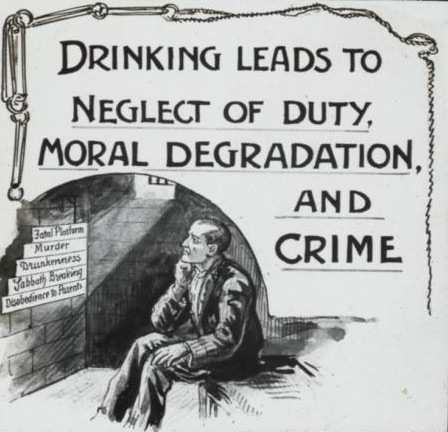

Teetotalism Reconsidered

Image Credit: http://diysolarpanelsv.com/images/tem...

Anyone who reads What’s So Confusing About Grace? will learn that I grew up within a teetotaling fundagelical church. Teetotalism is not simply the personal observance of total abstinence from alcohol but the advocacy for abstinence: i.e. I abstain … and here’s why you should too.

We had a blunt reason why you should give up alcohol: drinking is sinful. In short, we somehow turned “Be not drunk with wine” (Ephesians 5:18) into “Do not drink wine … or beer, spirits, or coolers.”

In my early years I had a conflicted reaction to teetotalism, but I finally gave it up completely when I was in high school. However, I don’t think a Christian should drink just anything. In my article “Would Jesus drink a Budweiser?” I gave an emphatic no, Jesus would not. The reason, however, was not because Jesus was a teetotaler but because Budweiser is insufferably bland. Jesus would support complex local microbrews.

Teetotalism has concerned me for years because I know its effects from the inside. I can still recall from my youth the sense of judgment and the air of superiority when we would see people drinking a beer or a glass of wine in a restaurant. I now recognize this attitude for what it was: a deeply corrosive legalism.

So when I saw that Michael Brown had written an article titled “Why I Never Drink Alcohol” I was intrigued. What do the ethics of teetotalism look like today? Has it escaped the shadow of legalism?

Brown begins his article by clarifying that he is simply stating his own personal reasons for abstaining from alcohol. He is not claiming that the consumption of alcohol is inherently sinful. I appreciate the qualification. Nonetheless, while Brown concedes that a Christian can drink alcohol, I read the deeper message of the article to be this: when all the risks and costs are calculated in, abstinence is the morally preferred option.

Brown lists several reasons for teetotalism. In the remainder of this article I want to consider the fourth because it strikes me as having particular rhetorical force:

A former alcoholic sees another brother or sister have a glass of wine with their meal, or they visit your house and see that you have beer in your refrigerator. They then think to themselves, “Well, if it’s OK for them, I guess it’s OK for me,” and they have one drink—just one—and quickly find themselves enslaved again, sometimes for years.

So, your liberty, which might be totally fine between you and the Lord, ends up destroying a precious brother or sister.

Paul addressed this in the context of food sacrificed to idols, but the principle is the same: “and by your knowledge [meaning, the knowledge that food itself doesn’t defile us] shall the weak brother perish, for whom Christ died? When you thus sin against the brothers, wounding their weak conscience, you sin against Christ. Therefore, if food causes my brother to stumble, I will never eat meat, least I cause my brother to stumble” (1 Cor. 8:11-13).

The lesson here is that we should put greater emphasis on helping weaker brothers and sisters than on enjoying our liberty.

I don’t take the general caution lightly. Brown definitely has a point: we should always consider the needs of those who struggle and we should put those needs ahead of personal interest. As a result, if I was out for lunch with an alcoholic I would refrain from ordering a beer with my meal.

But I am at pains to think how this point alone can possibly support abstinence and teetotalism. Consider my situation. I occasionally enjoy a rum and Coke on the back deck. Should I refrain from doing so on the off chance that one of my neighbors is (unbeknownst to me) a former alcoholic who might peak over the fence, inquire as to what I’m drinking, and thereby fall off the wagon?

Occasionally I meet friends for a beer at one of the local pubs. Should I refrain from doing so on the off chance that a struggling alcoholic might inadvertently see me walking into the establishment?

My answer is no. The risks of a person lapsing into a cycle of self-destructive alcoholism based on seeing me drink a rum and Coke or walk into a pub may not be zero, but they seem so negligible that this is simply not a reasonable concern.

And imagine if we did agree with Brown. Where do we stop? In his article Brown mentions the danger of being addicted to sweets. Should I abstain from ever eating chocolate on the off chance that somebody might otherwise fall off the dietary wagon and contract Type-2 Diabetes?

I love taking my motorcycle for Saturday afternoon cruises. Should I park it on the off chance that a former speed demon might see me riding and then decide to buy another motorcycle on which he shall end up losing his life in a fiery crash?

Clearly this is absurd. The lesson is that we do not make sweeping ethical decisions based on such far-fetched scenarios and negligible risks. To sum up, while I agree with Brown that we should exercise our freedoms with consideration for the struggles of others, his teetotalistic reasoning in support of abstinence appears to me suspiciously like a lingering legalism in search of a justification.

The post Teetotalism Reconsidered appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 22, 2017

God, Natural Disasters, and My Next Book

A few weeks ago I published an article at Strange Notions titled “Does God Punish People Through Natural Weather Events?” For some time I’ve been thinking about writing a book on the topic of whether God punishes human populations by way of natural disasters.

Well, this past week I finally got around to starting the project. My intent is to provide a fuller case for the claim I defend in the Strange Notions article according to which God does not and would not act in this manner. I’m currently at 18,000 words and hope to complete a rough draft of the entire manuscript (approximately 25,000 words or 100 pages) within the next week. From that point I’ll be fine-tuning the argument with the intent of publishing the book December-January.

The post God, Natural Disasters, and My Next Book appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 21, 2017

Gender-neutral Pronouns in Grade 5

A grade 5 teacher in Florida has requested that her students use gender neutral pronouns in the classroom.

Sorry, I should have said their students. As she (sorry, I meant they) writes: “my pronouns are ‘they, them, their’ instead of ‘he, his, she, hers.’ I know it takes some practice for it to feel natural but students catch on pretty quickly.'”

I hope they catch on more quickly than I do. (Just to clarify, I am referring here to the plural they, i.e. the students, rather than any singular they.)

Confusing? Definitely. But at least the teacher eschewed the more arcane gender neutral pronouns like xe, xi, and xir. The list of gender neutral pronouns is long … and growing. Good luck to grade 5 students facing this brave new world.

Oh yes, and the teacher, Chloe Bressack, also requests that they (by which I mean she) be referred to as Mx. Bressack (pronounced “Mix”).

Contrary to what you might think, I’m not necessarily disparaging the advent and use of gender neutral pronouns. The reality is that not everybody fits into the gender binary. (I’m thinking here specifically of people that are intersex though of course many people who are biologically and genetically male or female also chafe at their sex and/or gender identity.)

And Mx. Bressack certainly didn’t invent the awkward use of the singular they. Indeed, I recall entering university twenty-three years ago and coming to terms with the fact that the generic “he” and “man” was no longer acceptable in academic writing. I weathered that storm and soon came to adopt a range of of responses from he/she to the singular they to “humankind”.

So who knows how they (by which I mean both the entire grade 5 class and each individual of unspecified gendered within the class) will communicate tomorrow?

Brave new world, indeed.

The post Gender-neutral Pronouns in Grade 5 appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 20, 2017

Apologetics without the hardcore bit

A few days ago I received the following note from a friend who read What’s So Confusing About Grace?

Completed the book. Loved it. Was expecting some hardcore apologetics based on your interactions with atheists, but was very pleasantly surprised by the anecdotal, memoiristic, essay style.

My friend didn’t bother to define “hardcore apologetics”, but I think I know what he means: precisely defined and defended syllogisms and clearly defined debates with non-Christians. And from that perspective, he’s right: there is a noticeable absence of hardcore apologetics.

At first blush this might seem surprising. After all, I’ve been involved in my own share of hardcore apologetics over the years: I’ve authored a book of apologetics and co-authored two more in debate with atheists; I’ve debated atheists on the radio, podcasts, written form, and in formal debates in churches and on school campuses. And then there’s all that blogging.

All that is true. But it is also true that all this work has not had a large impact on my own personal process of doctrinal reflection and formulation. And that’s what this book is about.

That said, this book is full of apologetics. Throughout I find myself in debate with inadequate conceptions of the Gospel that I received from fundamentalism, dispensationalism, evangelicalism, and charismatic Christianity. Along the way, I seek to defend particular views of hell, heaven, the Bible, and the Christian life which redeem Christianity both from an intellectually arrested faith and some of the most existentially far reaching objections to that faith.

By the end I trust the reader will have a far better sense of what it is I believe, and why I believe it. That may not be hardcore, but it most definitely is apologetics.

The post Apologetics without the hardcore bit appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 19, 2017

My Book What’s So Confusing About Grace? is FREE Today

Kindle is doing a promo for my book What’s So Confusing About Grace? and as a result it is free for download for one day only … TODAY, SEPTEMBER 19TH!

Download it at Amazon.com here.

Download it at Amazon.ca here.

Download it at Amazon.co.uk here.

Spread the word, read, and review!

The post My Book What’s So Confusing About Grace? is FREE Today appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 18, 2017

Do atheists get their moral values from humanism?

This morning I came across the following tweet from Counter Apologist:

Humanism is where Seth & most of the atheist community gets our morals, and what Sargon has done runs way against ithttps://t.co/EJS4MtLT9J

— Counter Apologist (@CounterApologis) September 18, 2017

I think this is mistaken. For the most part, it seems to me that atheists don’t “get” (i.e. derive) their morals from humanism. Rather, to the extent that a philosophy of humanism is operative at all (and for many atheists it isn’t), humanism serves, rather, as an interpretive framework to explain, justify, and (to some degree) critique the morals one already has.

This works for Christians as well. For the most part Christians do not “get” their morals from the Bible or Christianity. Rather, the biblical text and their wider Christian commitments provide an interpretive framework to explain, justify, and (to some degree) critique the morals they already have.

The post Do atheists get their moral values from humanism? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Is it wrong for First Nations people to refer to non-indigenous people as “settlers”?

A few days ago a group of First Nations people were riding the LRT (mass transit) to the National Gathering of Elders at the Edmonton Expo Centre when they were stopped by transit police and asked for proof of purchase. The encounter that ensued has resulted in charges of racial profiling. While I don’t think the article to which I linked provides adequate evidence of racial profiling, the encounter is concerning and worthy of closer scrutiny.

But here I’d like to address the comment of one of those aggrieved indigenous leaders, Jocelyn Wabano-Iahtail. In the article she is quoted as follows:

“What happened on that deck is representative of what happens to us on a daily basis, and I am calling the settlers out and saying, ‘No more.'” (emphasis added)

I am sympathetic to Wabano-Iahtail’s frustration. I can’t imagine how infuriating it would be to be subject to subtle (and overt) forms of racial discrimination on a daily basis. And there is no doubt that First Nations people are among the most discriminated-against groups in Canada.

Having said that, I need to ask: is it reverse discrimination when indigenous people refer to non-indigenous people as “settlers”?

As I see it, there are two problems with the term “settlers”.

First, it is inaccurate. A settler is a person who settles a new territory. A majority of non-indigenous people are not, by that definition, settlers of Canada. On the contrary, they were born here and they’ve lived here all their lives.

So why does Wabano-Iahtail refer to non-indigenous people as settlers?

This brings me to the second point: it seems to me that the intent is at least in part to demean non-indigenous people within Canada. This raises many troubling questions including the following: if First Nations people can demean non-immigrants as “settlers” then by the same logic can an individual raised within Canada demean a recent immigrant?

Let me add that when groups that lack power use demeaning and discriminatory language the social implications are not as serious as when groups that possess power use demeaning and discriminatory language, not least because of the power differential.

Nonetheless, in both cases the language is demeaning and discriminatory. And to return to that lesson we all learned from our mother’s knee: two wrongs don’t make a right.

The post Is it wrong for First Nations people to refer to non-indigenous people as “settlers”? appeared first on Randal Rauser.