Randal Rauser's Blog, page 104

March 4, 2018

God Became Meat: A Devotional Reflection

I recently wrote a few devotionals for a forthcoming publication and I thought I would publish them at my blog as well. Here is the first.

John 1:14 “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.”

Every December, Christians around the world gather to watch the annual Christmas pageant. But for many of us, the extraordinary claim at the heart of that story, namely that God the Son became a human being, no longer shocks and stirs wonder as it once did.

That began to change for me some years ago when I was testing a new computer translation program. In order to evaluate the reliability of this program, I highlighted the Greek text for John 1:14 and then pushed the translate button. A moment later out came the result: “The Word became meat and dwelled among us.” Meat? That sounded positively blasphemous. I looked over my shoulder nervously, half expecting that a bolt of lightning might smite me for some sort of sacrilege. Can you say that? Can you say that God became meat?

But as the shock subsided, I had to admit that this crude translation did capture the literal essence of John’s claim. In the Greek, the text says that the Word, God the Son, became sarx, physical stuff, flesh, meat. If that makes you uncomfortable, then now you know how the Jews and Greeks felt when they first heard the claim two thousand years ago. This is definitely a plot twist that nobody saw coming.

Given the shock of the incarnation, it should be no surprise that over the years many Christians have tended to soften the radical notion of God becoming meat. Consider, for example, this line from the familiar Christmas classic “Away in a Manger”: “little Lord Jesus, no crying he makes.” Seriously? What infant child is this that he never cries?

On the contrary, the claim that God became meat suggests that infant Jesus did indeed cry; as a boy, Jesus grew in wisdom and favor with God and people (Luke 2:52); throughout his life, he experienced hunger (Mark 11:12), thirst (John 19:28), and exhaustion (John 4:6); he suffered (Hebrews 2:18), and he wrestled with the will of God the Father (Matthew 26:36-46); he was tempted as we are, yet remained without sin (Hebrews 4:15).

Let us never become too familiar with the shocking, wonderful fact that God the Son became meat.

The post God Became Meat: A Devotional Reflection appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 2, 2018

A Family Defense of the Resurrection of Jesus

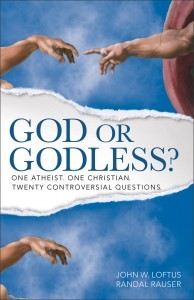

This article is based on a chapter in my 2013 book God or Godless, a collection of twenty short debates coauthored with atheist John Loftus.

This article is based on a chapter in my 2013 book God or Godless, a collection of twenty short debates coauthored with atheist John Loftus.

What would it take to persuade you that your brother is the long-expected messiah? Quite a lot, I suspect. You grew up with the guy. You saw him scrape his knee, fail algebra, accidentally break mom’s favorite teapot … and then lie about it. Is it any wonder that thinking of your sibling as the messiah strains your credulity far beyond the breaking point?

So perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised that when Jesus began to make messianic claims he too was met with skepticism from his siblings. We can know this because the gospels give no evidence that the siblings of Jesus supported him during his ministry. Indeed, in Matthew 12:46-50 Jesus quite intentionally distances himself from his family. Even more explicitly, John 7:5 states that “even his own brothers did not believe in him.” (NIV)

From the perspective of a historian, this detail is very significant. When historians assess the likelihood that a given historical claim is true, they appeal to several principles, and one of those principles is called the criterion of embarrassment. According to this criterion, historical claims which are embarrassing to one’s cause are more likely to be true because the individual would have no reason to lie about them. For example, if Dave tells you that he caught the biggest fish at the lake, you’d be skeptical because he could have a reason to lie about that. But if Dave tells you he caught a small fish, you’ve got a good reason to believe him. Surely he wouldn’t lie about that.

The fact that Jesus’ brothers didn’t believe in him is an embarrassing detail, like catching a small fish. Thus, it seems highly unlikely that this detail would have been fabricated. And that means that we have excellent historical reasons to believe that the siblings of Jesus – including his brother James – were not his disciples during his ministry.

Why does this detail matter? It matters because after the church was established, James not only became a disciple of his brother, but he even emerged as the de facto leader of the Christians in Jerusalem (see Acts 15:13; Acts 21:18; Gal. 1:19; Gal. 2:9; Gal. 2:12). Interestingly, this testimony is confirmed by Jewish historian Josephus in his work Antiquities (Bk. 20, ch. 9) where he observes that James was eventually martyred for his Christian faith.

To sum up, while James was a skeptic of his brother during his life, he became a disciple of his brother and a leader in the church after Jesus was crucified. The question is why? What persuaded this skeptic that his crucified brother was the messiah? After all, the Torah declares that “anyone who is hung on a pole is under God’s curse.” (Deuteronomy 21:23) So if anything, one would assume the crucifixion would have confirmed James’ skepticism. And yet, inexplicably, James became a leader of the Christians.

Again I ask, why? What changed James’ mind?

In fact, Paul provides the answer in 1 Corinthians (written about AD 55) where he recalls: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance….” (15:3) This language is technical rabbinical phrasing signaling that Paul is sharing an important teaching which he received, and which must be protected and passed on faithfully. Paul then explains that Christ died, was buried, and was raised back to life. He then lists several people who witnessed Jesus raised again and became converts as a result. And included in that list is James, the brother of Jesus.

But wait, if we’re acting as critical historians, then we should ask how a historian might explain this account. For starters, is it possible that this is simply a legend that grew over time? The answer is no. 1 Corinthians is written a mere twenty years after the events, and Paul is citing teaching in the letter that he received much earlier than that. There simply is not enough time for legend to develop.

So we must accept that James saw something. But is there a natural explanation? In short, could he have seen a vision, a hallucination? That seems very implausible. Remember, James was a skeptic of his brother’s ministry, so he had no expectation to see him raised again. Visions occur within a climate of background expectation. As a case in point, a hypnotist or magician doesn’t call the scowling skeptic in the audience up on stage. Instead, he chooses the fawning fan that is on the edge of her seat, ready to be manipulated. Skeptical James was not the fawning fan, and he was definitely not susceptible to seeing a vision.

So what did he see? I would submit that the best explanation for the extraordinary change in James is the one the church has always accepted. And it’s the same explanation that Paul gives us: James saw his brother raised from the dead.

And so we return to the question with which we began. What would it take to persuade you that your brother is the long-expected messiah? Speaking personally, I can say that my brother is a fine chap. But to believe he’s the messiah? That’d take nothing short of a miracle.

The post A Family Defense of the Resurrection of Jesus appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 1, 2018

Why is Billy Graham Lying in State?

This morning I posted the following question on Twitter:

Yesterday Billy Graham was honored posthumously as the fourth citizen ever to lie in honor at the U.S. Capitol. Graham, of course, is famous for a single reason: proselytization for a particular religion. Is this an appropriate honor in light of the American Establishment Clause?

— Randal Rauser (@RandalRauser) March 1, 2018

Based on the wording of the question, you can probably imagine the direction I lean. While I am a great admirer of Mr. Graham, it seems wholly inappropriate to me that a nominally secular state which disavows the establishment of any religion should offer a unique honor of lying-in-state to an individual whose primary distinction is being a prolific proselytizer for a specific religion.

The Daily Caller posted a revealing article in recognition of the event: “Thousands Find Unity In Honoring The Gospel And Billy Graham’s Legacy As He Lies In State.” I would simply ask Christians who agree with this display to imagine how they would feel if the roles were different such that it was a Muslim evangelist lying in state and it was the Five Pillars of Islam, rather than the Christian gospel, that was facilitating unity.

To the Christian who replies that the United States government favors Christianity, I would simply say, if the Golden Rule fails to persuade you, at least consider your own self-interest. You see, the state that can grant your religion special favor can also target it with special disapproval. And the political use of a particular religion to bring about social cohesion and further political ambition always exacts a cost.

The post Why is Billy Graham Lying in State? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 27, 2018

Feel free to sit on the fence, but don’t get caught in the lava flow

Some years ago the Jewish philosopher David Shatz wrote an essay titled “The Overexamined Life is not Worth Living.” That title could apply equally to chapter 31 of my 2012 apologetics book The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails.

Some years ago the Jewish philosopher David Shatz wrote an essay titled “The Overexamined Life is not Worth Living.” That title could apply equally to chapter 31 of my 2012 apologetics book The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails.

The book features an extended Socratic-styled dialogue between an atheist named Sheridan and a Christian apologist named Randal. And in this chapter, Randal challenges Sheridan with a challenge: decide how you will, but realize that any choice you make involves a risk.

And now without further ado, here is the chapter. Randal is speaking first.

“Okay, imagine that you live in a small town on an island nestled in the shadow of a massive volcano. For several years there have been rumbles and shots of steam and ash as the volcano has continued to threaten an eruption. One day a visitor in a uniform with an identity card marking him as a government official announces in the marketplace that a massive eruption is imminent and that anyone who does not leave the island immediately will be killed by the blast. Unfortunately all the boats are out for a two-week fishing trip and the only way off the island is on this man’s boat. The problem is that by leaving the island you effectively surrender your ownership of your land and house—thus leaving it to be claimed by any squatter who remains on the island.

“Clearly you’ve got to weigh your options carefully. If you leave the island and there is an eruption you’ll save your life, but if you leave and there is no eruption, you’ll lose your home. Conversely, if you stay and there is no eruption then you’re just fine, but if you stay and there is an eruption then you lose your home and your life. This leaves you with a serious dilemma, Sheridan. Do you get on the boat or not?”

“I’d hold back on making a decision so that I could gather more information from the boat owner, run a background check on his credentials, and get a second opinion from some volcanologists.”

“If you have the time.” I reply. “But do you? Since this is my thought experiment, I’ll tell you the answer: you don’t. At present you’re standing on the dock, smoke is curling up in growing plumes above the town, and the line up to get on the boat is growing longer by the minute. You have to make a decision now. So what are you going to do?”

Sheridan is unimpressed. “This sounds exactly like the high pressure evangelism sales tactics I grew up with. ‘Do you know where you’d go if you died tonight?’ You’re just using fear to try to pressure me into making a commitment to Jesus.”

“That’s not my point, Sheridan. I want you to take me seriously when I say that I’m not trying to convert you at this instant. I’m telling you the volcano story for two reasons. The first is that volcanoes are awesome.”

Sheridan’s groan is audible.

“And the second,” I continue, “is to point out that standing on the dock, or sitting on the fence, is not neutral. Whether you go forward, turn back, or stay where you are, you are making a decision. That doesn’t mean you need to let anyone pressure you into a new decision, but it does mean that it’s wrong to think you can just ‘sit on the sidelines’ until you reach whatever level of certainty you’re after. All of us are always in the game. Being a believer in anything brings risks with it, sure, but so does remaining a skeptic. We should be wary of the danger of doubt no less than of belief.”

“Fine, but that doesn’t change the fact that your beliefs are so flimsy. Take the doctrine of the trinity for instance. I take it that’s a pretty important belief for Christians.”

I nod. “Yup, it’s at the core of Christian identity.”

“Exactly. So how can you know that it is true? Maybe it is possible that there is a god. Maybe it’s even more likely than not. But even with that concession you’re still light years from confessing one god in three persons, aren’t you? What kind of mental gymnastics do you have to do to make yourself believe that?”

“Sheridan, I don’t disagree with apportioning your assent to the evidence. But that also means you can still believe those things for which the evidence is not as strong, but perhaps not with the same degree of conviction as some other things. For instance, a Christian could say that his belief in God is quite strong, but his belief that God is triune is less so.”

“Whoa, how can you be a Christian if you doubt the trinity?”

“I didn’t say a person would necessarily be doubting the Trinity. He could accept the proposition ‘God is three persons’. He just wouldn’t accept it with the same degree of certainty that he accepts some other propositions of the faith like ‘God is the most perfect being’ and ‘God is love’. Remember that the Jews were in a covenantal relationship with God without ever believing that God is three persons. This means that at one point in history God revealed himself as one but not yet three. Christians believe that later revelation then expanded and, in some sense, corrected the Israelites’ belief. With that in mind, it would seem to be possible that in the future God might expand and correct Christian beliefs in similar respects. How can we know this isn’t possible?”

Sheridan looks skeptical. “That sounds pretty wishy-washy to me. I’ll make it simple for you: do you believe in the trinity?”

“Of course I do. But it’s a big mistake to think that you need to hold all Christian beliefs with the same level of conviction, as if it’s one hundred percent certainty or not at all. I believe the doctrine of the Trinity, but I could see myself being wrong on that. It’s far harder to see myself being wrong on the existence of God. As for other doctrines, such as the nature and meaning of the Lord’s Supper, I have even less conviction.”

“Same thing with hell I guess, right?”

“It’s true that I’m not sure what to think about the doctrine of hell. I’m pretty sure that eternal conscious torment is not correct, though I could be wrong there, too. And if I am right, I’m not sure whether my present leanings toward annihilationism will be vindicated or whether my hope in the salvation of all might emerge triumphant. The point is that I can inhabit the Christian tradition, and even thrive within it, with all these remaining questions, doubts, and qualifications. To my mind, this isn’t being ‘wishy-washy’. It’s recognizing the complexity of belief. The good news, Sheridan, is that we’re not saved by how many beliefs we get right. We’re saved by being in relationship with God.”

“Right, your ‘acquaintance knowledge’. But beliefs still matter, don’t they?”

“Of course they matter, but salvation isn’t a matter of simply getting a certain number of correct answers on a multiple choice exam. It’s a complex process of moving into relationship with that being than which none greater can be conceived. And I believe that this being is the triune God who accomplished a redemptive work in Christ. That’s the boat I chose to board.”

“Well I’m staying on the dock. I’m not deciding anything until all the evidence is in. And if I get buried in a lava flow, then so be it.”

The post Feel free to sit on the fence, but don’t get caught in the lava flow appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 26, 2018

How the Ebola Virus Taught Me About the Gospel

This article is an excerpt from my book What’s So Confusing About Grace? And as a bonus, the Kindle version of the book is available for two bucks (that’s 75% off) until 8 am (Pacific Time) on Wednesday morning (Feb 28).

President Obama hugging nurse Nina Pham after she recovered from Ebola. Pham was infected while caring for Thomas Eric Duncan. Image source: White House Photographer Pete Souza, Public Domain.

What does it look like when people set aside their quest for personal health, happiness, and satisfaction in favor of a cross? I’m going to venture an answer to that question by way of an example of selfless service that captured my imagination a few years ago. I should add, however, that I don’t know if any of the people I’m about to describe are confessing followers of Jesus. But I do know this: their brave and selfless actions provided a moving illustration of what living faith looks like.

The time is September, 2014. The world has grown increasingly worried about an outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus when a young man named Thomas Eric Duncan arrives in Dallas, Texas from an Ebola hotspot: the country of Liberia in West Africa.

Shortly after arriving in the United States, Mr. Duncan falls ill and is taken to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. Not long after that, he is diagnosed with the highly contagious and nearly always fatal hemorrhagic fever: Ebola has landed on American soil. Do you remember the fear and uncertainty of that time when Ebola moved from being a terrible blight in some exotic overseas locale to one that had arrived on our proverbial doorstep? Those dark months in the fall of 2014 are seared into my memory because it felt for a time like we were living out the plot of a Hollywood disaster movie.

So now, let’s shift our attention back to the literal Ground Zero of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. Once Ebola had arrived, imagine how terrifying it would have been to go into work as an employee of that hospital. Every door handle, every railing, every elevator button, every breath of air could be concealing a deadly virus that would bring about a tortured, agonizing death in a matter of days. If I was on the payroll at Texas Health Presbyterian, I’d probably look for a reason–any reason–not to come into work. Why? I’ll be honest: I’m a coward. I’m afraid of suffering and I definitely don’t want to die. Long story short: I didn’t sign up for this.

Here’s the thing that still humbles and amazes me: despite the enormous risk to themselves, all the staff of the hospital–doctors, nurses, support staff, all of them–readily volunteered to provide care to Mr. Duncan. And what did that commitment look like? Just consider the job profile for the front line nurses. Day after day they dressed in double gloved hazmat suits. You need to understand that this was a stifling uniform that left them soaking in sweat within minutes. Uncomfortable though it may have been, it was essential protection against the deadly virus. Next, they would enter the quarantined area where Duncan was being housed, a nightmarish twilight zone stranded between death and the land of the living.

Once there, the nurses would set to work, hydrating Duncan, comforting him, and changing his clothes. As you can imagine, the scene was a living hell: Duncan emitted copious amounts of diarrhea, projectile vomiting, and blood, and all of it was toxic hazardous waste. The minute they entered the room those caregivers were placing their very lives at risk. And yet, the nurses would still work 16 to 18 hour days taking turns on two hour shifts in their full hazmat gear, and all to care for one desperately ill man.

A couple months after Duncan passed away, 60 Minutes did a story which featured interviews with some of these extraordinary caregivers. One of these brave individuals, a man named John, shared his recollections of caring for Duncan. He recalled: “we held his hand and talked to him and comforted him because his family couldn’t be there.” As I watched John recalling his time serving Duncan, I found myself amazed by his compassion in the midst of the worst horrors. He continued, “He was glad someone wasn’t afraid to take care of him. And we weren’t.”

Two nurses–Nina Pham and Amber Vinson–contracted Ebola as a result of treating Mr. Duncan. Both eventually recovered.

Wow.

Well I’ll tell you this: I would have been afraid. In our culture soldiers, police officers, and firefighters receive well-deserved credit for their courage in meeting the call of duty. By contrast, one doesn’t typically use the words “brave” and “nurse” in the same sentence. But the nurses of Texas Health Presbyterian are some of the bravest people I’ve ever seen.

Despite the heroic efforts of his caregivers, Duncan continued to decline until he was hooked up to a respirator, heavily sedated, with tears streaking down his cheeks. Against this heartbreaking backdrop, John describes his final moments with Duncan:

And I grabbed a tissue and I wiped his eyes and I said, “You’re going to be okay. You just get the rest that you need. You let us do the rest for you.” And it wasn’t fifteen minutes later I couldn’t find a pulse. And I lost him. And it was the worst day of my life. This man that we cared for, that fought just as hard with us, lost his fight. And his family couldn’t be there. And we were the last three people to see him alive. And I was the last one to leave the room. And I held him in my arms. He was alone.

As John shares these recollections, tears begin to roll down his face and his voice shakes. The emotions are clearly still raw. And when he says that was the worst day of his life, I believe him.

To be sure, had I been there, I might also have said it was the worst day of my life . . . but for very different reasons. I would’ve considered it my worst day because I’d have to risk my life while suffering in a stifling hazmat suit cramped in a room with a dying man and vats stuffed with towels and cloths infected with toxic diarrhea and vomit. By contrast, it was the worst day of John’s life because he lost a patient he had cared for and loved, a man who tragically suffered greatly and died alone. There’s a big difference between John and me, that’s for sure. I don’t know if John’s a Christian, but I know which one of us looks more like Jesus.

The post How the Ebola Virus Taught Me About the Gospel appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 24, 2018

Should evangelical institutions require belief in eternal conscious torment?

In 1996 I graduated from Trinity Western University in Langley, BC. For years TWU has been (so I would argue) Canada’s flagship liberal arts evangelical post-secondary institution. Unfortunately, its evangelical identity has long included some fundamentalist roots. For example, when I attended TWU in the mid-1990s students were required to sign a lifestyle covenant stating that they would refrain from consuming alcoholic beverages or engaging in “social dancing”. (Presumably, anti-social dancing — e.g. the mosh pit — was okay.)

The good news is that TWU’s revised 2009 lifestyle covenant has removed the prohibitions on alcohol and dancing. Instead, the document calls on all students, faculty, and staff to exercise wisdom and discretion in their recreation and beverage choices. I can certainly agree to that. (At the same time, the statement does continue to banish alcohol from campus, so the TWU campus pub is still a ways off.)

In 2009 TWU also adopted a revised Statement of Faith. Unfortunately, vestiges of a questionable theological conservatism (if not fundamentalism) still remain in this document. In order to teach at the institution, you need to sign a statement consisting of ten confessions:

“I agree with the above Statement of Faith and agree to support that position at all times before the students and friends of Trinity Western University.”

In most cases, the expectations are very reasonable for any evangelical or Protestant institution. However, paragraph 10 raises a significant concern for me because it includes a confession that the lost will experience eternal conscious torment in hell:

“We believe that God will raise the dead bodily and judge the world, assigning the unbeliever to condemnation and eternal conscious punishment and the believer to eternal blessedness and joy with the Lord in the new heaven and the new earth, to the praise of His glorious grace.”

Note that this demand would exclude many evangelicals from teaching at TWU including the late John Stott, arguably the most widely respected evangelical public intellectual of the latter half of the twentieth century. (Stott was a well-known annihilationist.)

Evangelicals like Stott have excellent reasons for endorsing alternative views of posthumous judgment. Those reasons include biblical, theological, philosophical, historical, and practical considerations. To my mind, the only reason that one would retain such a contentious doctrine as ECT within a statement that is purportedly aimed at representing a broad and basic evangelical commitment is practical in nature: in short, removal of the eternal conscious torment requirement would upset a particular conservative constituency (read: donors).

I will leave it to the reader whether that is a satisfactory reason to continue to require all TWU faculty and staff to believe — or at least publicly defend — the claim that the lost will experience eternal, unimaginable torment in body and mind.

The post Should evangelical institutions require belief in eternal conscious torment? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 23, 2018

To Cremate or Not To Cremate?

A few weeks ago, I posted the following Twitter survey on cremation:

Historically, the church rejected cremation in recognition of the value of the body and anticipation of the bodliy resurrection. Today, however, many Christians cremate. Forgive me if this is too forward, but what are your posthumous plans?

— Randal Rauser (@RandalRauser) February 2, 2018

Of course, the scientific value of my Twitter surveys is zero (within three percentage points, 19 times out of 20). Nonetheless, they do serve to get a conversation going. And in this case, the conversation is this: should Christians cremate?

To begin with, we should be clear that the question is not whether God has the ability to resurrect a body once cremated. If God can resurrect a body at all, he surely can resurrect a body that was once cremated.

The question, rather, is whether the symbolic value of resurrection obliges the Christian to seek resurrection, even when doing so is impractical and even costly.

As I note in the question, the church has historically said, “yes”. And that includes notably, the church in Rome where Christians excerpted enormous effort in building catacombs to house the dead and honor their hope in the resurrection of the body.

Today, however, attitudes are changing. My anecdotal experience in speaking to Christians about their posthumous plans bears out this fact: many Christians tell me they plan to cremate. So what should we say? Should these individuals be censured?

I will say that there are bad reasons to seek cremation. For example, some people I have spoken to say they prefer cremation because they don’t want their body to rot. They don’t like the thought of maggots and bacteria consuming their mortal coil. I share their aversion to the thought, but I don’t think that is a sufficient reason to reject the church’s traditional position in light of the symbolic significance of the body in anticipation of the resurrection.

Having said that, I do think that reasonable grounds for preferring cremation are readily available. In 1992, I backpacked through Hong Kong and I still remember the dizzying experience of block after block of forty-story buildings packed together with teeming hordes of people crowding the streets. Needless to say, one would need to be very wealthy to pay for a burial plot in Hong Kong. Should the Christian church in Hong Kong divert resources that would otherwise go to feeding the poor toward financing burial plots for Christian members?

Absolutely not. There is no way I could justify that use of resources. And as a result, it seems to me undeniable that practical factors like economic cost could override the symbolic significance of traditional burial and thereby even require one to seek cremation.

However, rather than conclude that we are simply giving up any symbolic valuation in the body after death, it would be preferable, all things being equal if there is a viable way to theologize the act of cremation (that is, to interpret the act symbolically in accord with one’s theological beliefs).

And I think there is: as one of my students recently suggested, cremation could be viewed in the terms of the refiner’s fire (e.g. Malachi 3:3; 1 Corinthians 3:15), a posthumous symbol of fire as a purging/cleansing agent. As the physical body undergoes the fire of purgation at death, so the individual will undergo a purgation prior to resurrection. Yes, this would correspond readily to the image of fire in the Catholic doctrine of purgatory, but for the purgatory-averse Protestant, it could refer simply to the fact that nothing impure shall enter God’s kingdom (Revelation 21:27).

One more thing: we live in an extraordinary age in which a person’s organs can be used to give life to other people. With that in mind, I would suggest that the very best choice for one’s body is to become an organ donor (Matthew 7:12; Mark 12:31; John 15:3).

The post To Cremate or Not To Cremate? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 21, 2018

Would you disciple a Muslim child against his parents’ wishes?

Yesterday on Twitter I posed the following question:

Your 15-year-old Muslim neighbor is really interested in Christianity, but his parents have forbidden him from going to church. He just asked you to help him defy his parents' wishes by secretly taking him to church youth group. Do you agree?

— Randal Rauser (@RandalRauser) February 19, 2018

It’s notable that a plurality of respondents would defy the wishes of the Muslim parents by taking their child to church. Of course, I understand the reasoning behind that response. But I do not agree. When I contemplate the question I find myself stalled at the Golden Rule. If I would not appreciate parents of another religion deceiving me and subverting my parental authority, I cannot justify deceiving parents of other religions and thereby subverting their parental authority.

That said, I can anticipate this reply. “Okay, but let’s follow that logic out to its terminus. If you were a border guard you wouldn’t want people smuggling contraband across the border, right? So by that logic, it would be wrong for you to smuggle Bibles across the border!”

My imaginary objector is right. That would seem to follow. And yet, I’m okay with smuggling Bibles. So what’s going on here?

The fact is that in both cases, we have a conflict of obligations. We have obligations to respect parents and to help willing children have access to a church. And we have obligations to respect border authorities and to distribute Bibles as widely as possible. And in each case, we need to decide which obligation will trump the other. I believe the obligation to disburse the Bible widely trumps my obligation to respect the repressive orders of border guards. But I believe my obligation to respect the authority of parents (except in extreme cases) trumps my obligation to ensure that their willing children have access to a church.

There’s much more I could say at this point about why I believe the authority of Muslim parents trumps my obligation to help their willing children access a church. But instead, I think I’ll throw it open to others to share your opinions on the question.

The post Would you disciple a Muslim child against his parents’ wishes? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 20, 2018

Is God’s Love “Reckless”?

Over the last couple weeks, I’ve heard the song “Reckless Love” played at two different churches. It’s a catchy song and the YouTube video, posted just one month ago, already has more than a million hits. In short, it’s all but bound to become a Sunday morning staple. But what about the song’s central claim that God’s love is “reckless”? What should we make of that? (For the full lyrics click here.)

The Problem

Let’s start with a definition of “reckless”:

reckless. “utterly unconcerned about the consequences of some action; without caution; careless.” (source)

So to act in a reckless manner is to act without caution; it is to be careless, to show no concern for the consequences of one’s actions.

With that in mind, is God reckless?

Well, let’s keep in mind what we mean by “God”. In the Christian tradition, God is understood to be (among other things) omniscient (i.e. all-knowing) and maximally wise (i.e. exercising perfect judgment).

So does it make sense to say that a being that knows all things and always exercises perfect judgment could act without caution, carelessly, with no concern for their actions?

No, it doesn’t. As omniscient, God always perfectly knows every consequence of every action. As perfectly wise, he always acts with flawless judgment in every circumstance. God simply cannot act recklessly by definition.

Case closed?

The Careless Action Defense

Maybe not.

Interestingly, the music leaders at both churches apparently recognize the tension because each introduced the song to the congregation with an unusual apology in which they defended the claim of God’s recklessness, in part by reading excerpts of an apology for the song on behalf of the songwriter. The main gist of the defense was the claim that while God himself isn’t “reckless”, his love nonetheless is.

Unfortunately, that’s nonsensical. It’s like saying “Jim isn’t violent, but his temper is”. Let’s be clear: if Jim’s temper is violent then it follows that Jim is violent. Pari passu, if God’s love is reckless then it follows that God is reckless. Period.

And God most certainly isn’t reckless.

So … case closed now?

The Hyperbole Defense

Maybe not.

At this point, I’d like to explore a second defense, one which appeals to idiomatic interpretation of the ascription. While there are several literary devices that one could conceivably appeal to in this case (in particular, irony, oxymoron, or paradox), in my view the strongest candidate is hyperbole, and so that is the interpretation that I will consider here.

Here’s the definition of “hyperbole” from the Literary Devices website:

A hyperbole is a literary device wherein the author uses specific words and phrases that exaggerate and overemphasize the basic crux of the statement in order to produce a grander, more noticeable effect. The purpose of hyperbole is to create a larger-than-life effect and overly stress a specific point. Such sentences usually convey an action or sentiment that is generally not practically/ realistically possible or plausible but helps emphasize an emotion. (Source)

Is “reckless love” an example of hyperbole? At first blush, the answer might seem to be no. After all, hyperbole is exaggeration for effect. For example, if you’re hungry, you might hyperbolically say “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse!” Of course, you’re not really that hungry, but note that the hyperbolic description nonetheless exists on a continuum of hunger. “I’m so hungry I could at a burger … a pizza … a horse!”

But recklessness doesn’t seem to exist on a parallel hyperbolic continuum, does it?

Actually yes, it does. Consider this example. Dave says to Darlene: “Oh Darlene, I love you so much that I can’t see straight!”

The parabolic continuum here is one of personal incapacitation. “I love you so much I think about you often … think about you always … can’t even see straight!”

Just as the intensity of Dave’s love is hyperbolically described as inhibiting his oracular faculties, so the intensity of God’s love is hyperbolically described as inhibiting his critical thinking faculties to the point where he is reckless.

Love … or juvenile infatuation?

So it seems to me that “Reckless Love” presents us with a case of hyperbole. The question is whether it is a successful hyperbole.

The primary problem, as I see it, is that the hyperbolic description of recklessness connotes not the mature, steady love of God but rather the unstable, unreasonable infatuation of an impulsive young adult. (The image that comes to my mind is the final scene of Sing Street where the young teenage lovers get into a boat and set out for England: it’s an absurd action all but doomed to failure. And yet, that’s the unreasonable reckless infatuation of a young adult.)

Calling God’s love reckless distorts that love by comparing it to youthful infatuation that acts in an impulsive and irrational manner based on intense but wavering feelings. Contrast this with Paul’s description in Ephesians 1:

3 Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in the heavenly realms with every spiritual blessing in Christ.4 For he chose us in him before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight. In love 5 he predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ, in accordance with his pleasure and will— 6 to the praise of his glorious grace, which he has freely given us in the One he loves. 7 In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins, in accordance with the riches of God’s grace 8 that he lavished on us. With all wisdom and understanding, 9 he made known to us the mystery of his will according to his good pleasure, which he purposed in Christ, 10 to be put into effect when the times reach their fulfillment—to bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ.

God’s love is the very antithesis of recklessness.

What is more, when God asks us to live out Christ’s love he challenges us likewise to set aside the intensity of wavering infatuations and instead soberly count the cost:

26 “If anyone comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters—yes, even their own life—such a person cannot be my disciple. 27 And whoever does not carry their cross and follow me cannot be my disciple.” (Luke 14)

Conclusion

To sum up, God’s love is not reckless: it cannot be. Nor, in my view, is it helpful to think of God’s love as hyperbolically reckless because doing so frames God’s love as a youthful infatuation rather than the abiding, steady, well-planned, and eminently non-reckless love through which we were chosen before the creation of the world and for which we have been called soberly to count the cost.

The post Is God’s Love “Reckless”? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 18, 2018

Does Christianity promise that everything sad is going to come untrue?

Today I visited a church in which the speaker addressed the problem of evil. Near the end of the sermon, he appealed to this famous quote from The Lord of the Rings:

“I thought you were dead! But then I thought that I was dead myself! Is everything sad going to come untrue?”

The speaker then observed that yes, it is in fact so. According to Christianity, everything sad will indeed come untrue.

But this isn’t actually correct. Christianity doesn’t claim that everything sad will come untrue. Christianity is consistent with various eschatological theories (i.e. accounts of the final order of things) including three main accounts of the final state of the lost. And only one of those is consistent with the claim.

The main theory of the fate of the lost is that they will experience eternal conscious torment, a state of never-ending alienation from God where the lost suffer unimaginable torment in body and mind forever.

If anything is sad, that most surely is. And on this account, this enduring horror will never come untrue.

According to the second account, the lost will be resurrected to face a final punishment that will result in their ultimate destruction culminating in annihilation into non-existence. While this scenario is undoubtedly preferable to eternal conscious torment, it also ends in what is effectively the capital punishment of an indeterminate number of human creatures. That too is surely sad. And it shall never come untrue.

The final view, universalism, insists that as bad as things are now, and however bad they may become, nonetheless, eschatologically all things — including the lost — will finally be reconciled to God in Jesus Christ. Only at that time, and under this very specific scenario, will everything sad indeed come untrue.

So to sum up, Christianity does not promise that everything sad will come untrue, but universalistic Christianity does. That may constitute a reason to consider universalistic Christianity, but that reason must be weighed along with all the other cumulative arguments (biblical, theologial, practical, philosophical, etc.) for and against the view. Suffice it to say, until one has a settled opinion on the matter, one ought to refrain from making claims about Christian doctrine that are not borne out by the facts.

The post Does Christianity promise that everything sad is going to come untrue? appeared first on Randal Rauser.