Randal Rauser's Blog, page 102

April 7, 2018

Ain’t Gonna Make a Monkey Out of Me! Is Darwinism Compatible with Human Dignity?

Over the years, I’ve encountered many objections to the reconciliation of Christianity to Neo-Darwinian evolution. One of the most common and forceful objections pertains to the alleged loss of human dignity that comes with a biology of common descent. As Christian rock singer Larry Norman sang in “God Part III,”

Over the years, I’ve encountered many objections to the reconciliation of Christianity to Neo-Darwinian evolution. One of the most common and forceful objections pertains to the alleged loss of human dignity that comes with a biology of common descent. As Christian rock singer Larry Norman sang in “God Part III,”

“I don’t believe in evolution. I was born to be free.

“Ain’t gonna let no anthropologist make a monkey out of me.”

In other words, the notion of common descent between human beings and other lifeforms presents a significant objection to Neo-Darwinism. Common descent is irreconcilable with human freedom, dignity, and the image of God.

But is it? In this article, excerpted from my 2011 book You’re Not as Crazy as I Think, I challenge the assumption that common descent is incompatible with human dignity. There may be some good objections to evolution, but in my view, this is not one of them.

Gather together as much evidence in favor of evolution as you like and some people will still reject it without a second thought for they are utterly convinced that evolution must be false. One reason for this certainty comes back to Hodge’s conviction that Darwinism is atheism, and if not quite atheism, then something in the neighborhood. This is the way Henry Morris put it: “One can be a Christian and an evolutionist, just as one can be a Christian thief, or a Christian adulterer, or a Christian liar. It is absolutely impossible for those who profess to believe the Bible and to follow Christ to embrace evolutionism.”[1] Boiled down to essentials, the argument goes something like this:

(1) I am certain that Christianity is true.

(2) If Christianity is true then Darwinism is false.

(3) Therefore, Darwinism is false.

It is hardly surprising that people motivated by this type of reasoning are no more likely to consider evolution seriously than they are likely to consider polygamy, murder, or Wicca. But is the reasoning itself sound?

For many evangelicals, confirmation of their antagonism toward evolution came in the 2008 pro-intelligent design documentary Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed (a film that Ted first saw on the big screen at his church). In the film, the comedian Ben Stein determined to investigate the alleged marginalization of intelligent design by the scientific establishment. While concerns about academic freedom and censorship are prevalent in the film, we do not need to probe far beneath the surface to find the smoldering sentiment that Darwinian evolution is fundamentally incompatible with Christian convictions. To this end, Stein interviewed a number of atheists in the film who claimed that Darwin is irreconcilable with faith.

For instance, atheist Will Provine declared: “No god, no life after death, no ultimate foundation for ethics, no ultimate meaning in life, and no human free will are all deeply connected to an evolutionary perspective. You’re here today and you’re gone tomorrow and that’s all there is to it.” If Provine is correct, evolution contradicts a number of essential Christian doctrines. This certainly is a startling claim, but rather than assess it critically, Stein simply accepted it with the observation that “Dr. Provine’s deconversion story was typical amongst the Darwinists we interviewed.” The point is further hammered home when Stein interviewed atheists Richard Dawkins and P. Z. Myers who are also well known for their unremitting hostility toward religion. And so Stein concluded, “It appears Darwinism does lead to atheism.” Hodge, it would seem, is vindicated.

While the perspective of Provine, Dawkins, and Myers deserves to be heard, we might wonder why Stein didn’t interview any of the thousands of Christian theologians and scientists who are Darwinians. In fact, he did. He just didn’t let the viewers know about it. In the film, Stein interviewed two theistic evolutionists, Alister McGrath and John Polkinghorne, both respected theologians with extensive training in science (indeed, Polkinghorne was once a theoretical physicist). Sadly enough, while Stein invited McGrath and Polkinghorne to share their views on the compatibility of Christianity and science, he never invited them to share their perspective on the compatibility of Christianity and Darwinian evolution.

Stein also interviewed Eugenie Scott, the executive director of the National Center for Science Education. While Scott is an atheist, she did not agree with Provine, Dawkins, and Myers that Christianity and evolution are incompatible. Indeed, she observed that “the most important group we work with is members of the faith community because the best-kept secret in this controversy is that Catholics and mainstream Protestants are okay on evolution.” Clearly, Stein was not happy with Scott’s claim and so her comment was immediately followed by journalist Larry Witham’s incendiary rejoinder that Christian evolutionists are “liberals” who side with Darwin simply because of their deep antipathy toward religious conservatives. When he made this startling claim, Witham added another charge to explain why some assent to Darwinism: irascibility. That is, they opt for evolution because they just trying to stir up trouble among the faithful, rather like soccer hoodlums pouring out of an English pub in search of a good brawl.

But this additional option hardly helps us dismiss the carefully reasoned scientific and theological support for Darwin’s theory offered by thoughtful scientist-theologians like McGrath and Polkinghorne. Witham followed his implausible irascibility charge by affirming Provine’s claim that Darwinism and atheism are linked: “Implicit in most evolutionary theory is that either there is no god or god cannot have anything, any role in it. So naturally, as many evolutionists will say, it’s the strongest engine for atheism.” It may well be that some Christians are attracted to Darwin because of their antagonism toward conservative Christianity. But can that plausibly explain the temperate and well-articulated position taken by McGrath, Polkinghorne, and tens of thousands of other Christians?

As I said at the beginning of this section, some Christians are apparently moved to adopt sweeping condemnations of evolution (and its sympathizers) based on the assumption that it is simply incompatible with Christian faith. In addition, it also seems to be assumed that acceptance of Darwinian evolution will lead to great evil and suffering. For evidence of this, we need only observe that many dissenters from Darwin have linked the theory with the horrors of Nazi Germany, and there is no more rhetorically effective charge than this.[2] This shocking link should give us a sense of the seriousness with which many view the rise of Darwinian evolution.

To get a sense of the urgency, put yourself back into Germany in the 1930s for a moment. Imagine that you are a witness to the rise of the Third Reich. Although many of your Christian friends are enthusiastic about Hitler, you are convinced that his political ideology will lead to the proliferation of evils like fascism, neo-paganism, and anti-Semitism. Once you have drawn these conclusions, the fact that a pro-Nazi consensus emerges in the German Lutheran Church would carry no persuasive force for you whatsoever. Indeed, you would be insulted by a friend who would attempt to persuade you to join the Nazis by appealing to a long list of pro-Nazi theologians and church leaders. Consequently, you would not shy away from dismissing all those in this pro-Nazi consensus list as being either ignorant of Nazism’s true nature or as culpable supporters of a truly demonic regime.

Against that extreme backdrop, imagine a 1930s Bill Maher interviewing a Nazi-fighting Ken Ham. Nazi Maher points out that “scientists line up overwhelmingly on the pro-Hitler side of this issue. It would have to be an enormous conspiracy going on between scientists of all different disciplines to have such a consensus. That doesn’t move you?” To this, Nazi-fighting Ham offers his resolute reply: “No, not at all, because from a biblical perspective I understand why the majority would not agree with the truth. Man is a sinner. Man is in rebellion against his Creator.” While Ham’s sweeping dismissal of current scientific consensus is indefensible, when we place it against the backdrop of a fear tantamount to Nazism, it becomes understandable, even admirable. We should keep this in mind when we countenance the overwhelming support that apologists like Ham receive from many in the mainstream conservative Christian population.

But even if that is the way crusaders like Ham are often perceived by their devotees, it merely begs the question of whether there are good reasons to believe that the theory of evolution will lead to evils akin to those committed by the Third Reich. Could it really be, as Expelled implies, that Darwinism clears the way for horrifying ideologies like Nazism? Obviously, Darwinism is not anti-Semitic per se. So insofar as we see a link, it would arise from the perception that Darwinian evolution undermines human dignity generally, thereby clearing the way for abuses of human dignity like anti-Semitism.

The concern is summarized in the title of Moody Adams’ little booklet Don’t Let the Evolutionist Make a Monkey out of You.[3] This title implies that Darwinian evolution is stupid since to make a monkey out of somebody is to show them to be stupid or gullible, in this case by convincing them that something absurd is true. (The guy who convinced you that you could become a millionaire by investing five hundred bucks in his pyramid scheme made a monkey out of you. The Darwinist who aims to convince you that you’re descended from monkeys is angling to do the same.) The title also has another, more somber, implication: Darwinian evolution undermines human value or dignity.[4] In this sense, the Darwinist makes us into monkeys by undermining human worth. In other words, if we are merely animals then we might as well live like animals.

But how does Darwinian evolution undermine human value exactly? Presumably the core problem is that of humble origins: once we accept that human beings share common ancestry with chimps (and indeed with the sea cucumbers at the city aquarium and even the algae growing in that kiddie pool sitting in your neighbor’s backyard), it is impossible to retain any notion of our unique dignity and value.

Perhaps we might illustrate the problem by considering the sobering story of the Cadillac Cimarron. Back in the early 1980s, Cadillac decided to develop an entry-level automobile to introduce people to the marque, the idea being that after a good experience with the car, these customers would trade up to a higher priced model. Based on that reasoning the Cadillac Cimarron was unveiled in 1982—to an appalled public. The central problem was that Cadillac decided to develop the Cimarron on the cheap by basing the car on the Chevy Cavalier, a vehicle so bland that it would have blended right in on a communist-era East German car lot. In retrospect, the whole project was doomed from the start, for no serious, brand-conscious Cadillac consumer would ever buy a rebadged and overpriced Cavalier. Once the Cimarron’s humble origins were known, its fate was effectively sealed.

According to the argument, the same problem of humble origins that sealed the fate of the Cadillac Cimarron besets the human being who is revealed to have a humble origin. If we conclude that we share common ancestry with nit-picking monkeys (let alone freaky sea cucumbers and scummy algae), we lose our special worth as surely as the much-loathed Cimarron. At best we are, as Desmond Morris infamously put it, The Naked Ape,[5] while at worst we are little more than overpriced bags of oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen. As for “image of God,” you might as well put a Gucci label on a garbage bag. Not surprisingly, severe consequences follow, for once human beings lose their intrinsic worth, the way is open for the descent into genocidal mutinies and other untold horrors: Hitler, here we come.

Sounds extreme you say? Well, consider that the London Zoo gained headlines in the summer of 2005 when it unveiled a display featuring eight human beings living “in their natural habitat” (though mercifully not “au naturel”—they were sporting swimsuits with pinned on fig leaves). The people were free to walk around the enclosure, sun themselves on the rocks, and wave to passersby. The sign on the enclosure identified the strange creatures as homo sapiens and it went on to describe their natural habitat and diet. The zoo spokeswoman explained the subversive point of the display as follows: “Seeing people in a different environment, among other animals . . . teaches members of the public that the human is just another primate.”[6]

It is that “just” that is so worrisome: just another primate; just another biped; just another mammal; just another creature. And once you have dehumanized humanity, we have set the conditions to treat human beings as objects. This, in turn, clears the way for the resurgence of demonic ideologies like Nazism. And if Darwinian evolution makes smooth the road to Nazism, we ought to fight it with unqualified vigor, even if that means dismissing Darwin’s many supporters either as hopelessly uninformed baboons or the Devil’s henchmen.

I agree that we ought to be extremely careful about any scientific theory that seems to undermine human dignity and thereby make possible the rise of militaristic and genocidal ideologies. But does evolution really do this? That is, does the claim that human beings share common ancestry with monkeys, sea cucumbers, and even lowly algae lead to a fatal denigration of human value? Frankly, I find this charge to be puzzling. After all, each one of us came from a sperm and an egg, neither of which is of much value in itself. Nobody laments the egg lost at every menstrual cycle, let alone the millions of sperm doomed to perish with each coital act. And yet, despite the terribly low status of egg and sperm, nobody worries that our humble origins in the union of the two somehow denigrates human value.

Why?

Surely the answer is obvious: however lowly our origins, we are not mere ova or sperm. Nobody would argue that because we come from the union of sperm and egg, we are nothing but glorified sperm and egg. But then why think that if we come from an evolutionary process from primitive single cellular organisms that we are therefore nothing but glorified primitive single cellular organisms? Surely our extraordinary achievements provide ample empirical evidence of humanity’s unique status. Just consider the sonnets of Shakespeare, the art of Angelico, and the physics of Feynman (not to mention the ganache cake of celebrity chef Ina Garten).

Is it possible to get beyond the visceral “yuck factor” of thinking of chimps and algae as distant cousins? Can we find a more robust argument to demonstrate how common ancestry might be incompatible with human uniqueness? In order to answer that question, we should begin by identifying that set of qualities that are seen to distinguish human beings as having unique dignity and worth. Within biblical theology that unique status is commonly identified as the image (and likeness) of God. So the humble origins objection really amounts to this: the notion of human beings sharing common ancestry with other life forms is incompatible with at least some of the unique characteristics of the image of God. Just as being married is incompatible with the concept bachelor, so the claim goes, sharing common ancestry is incompatible with the concept of the image of God.

Now here lies the difficulty. While the contradictory nature of a married bachelor is clear enough given the lucidity of the concept of bachelor, the concept of “commonly descended divine image bearer” does not likewise seem obviously contradictory. This is hardly surprising given that there is so much controversy on what the image of God even is. In Scripture, we have only a smattering of texts that refer to the image or likeness of God (Genesis 1:26-7; 5:1; 9:6; 1 Corinthians 11:7; 15:49; James 3:9). What is striking about these texts is that they provide no clear picture of what the image (that is, the essence of human uniqueness) consists. As a result, there is no reason to believe that common ancestry is incompatible with the image. These texts simply do not provide sufficient grounds to conclude with confidence that a creature made in the image of God could not share common descent with other creatures that do not.[7]

One final point is worth mentioning. Even if there was evidence that image and or likeness of God was somehow incompatible with common descent, we could still countenance the possibility of evolution, while adding that God intervened in the evolutionary process (perhaps uniquely at the creation of Adam) in such a way that he brought human beings a quantum leap beyond our nearest ancestors so that we could be divine image bearers. When we consider this additional possibility I simply find no evidence to think that Darwinism necessarily undermines human dignity. And that means that I find no ground to justify the sweeping dismissal of the Darwinist in a way parallel to the sweeping dismissal of a Nazi-sympathizer.[8]

Much remains to be said of course. One remaining elephant in the room concerns the way to interpret Genesis 1-3. Is it to be read as a straightforward historical narrative, as so many Christians assume? Here I will simply observe that many Old Testament scholars believe that Genesis 1-3 is not a historical narrative with scientific implications and thus that there is no conflict between this ancient text and contemporary Darwinism.[9] Here again, my point is not that this type of non-historical reading is necessarily the best one. Rather, it is simply that many Christians adopt such a reading of Genesis with knowledge of the text and without any wicked intentions.

[1] Henry Morris cited in R.J. Berry, God and Evolution: Creation, Evolution, and the Bible (Vancouver: Regent College Publishing, 2000), 13.

[2] See my article “It’s just like Nazi Germany . . . ” at http://www.christianpost.com/blogs/tentativeapologist/2009/09/its-just-like-nazi-germany-30/index.html

[3] (Evangelistic Association, 1981).

[4] This rhetorical tactic has been around for awhile. As historian Michael Lienesch observed of the fundamentalist controversies in the 1920s, “Debates on evolution were littered with satiric references to ‘monkey business,’ ‘monkeyshines,’ ‘monkeyfoolery,’ and the like. But while both sides made use of such phrases, antievolutionists used them more easily and effectively, particularly in casting derision at the alleged biological relationship between monkeys and humans.” In the Beginning: Fundamentalism, the Scopes Trial, and the Making of the Antievolution Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 100.

[5] (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967).

[6] Cited in Kevin Kechtkopf, “Humans on Display at London’s Zoo,” (August 26, 2005), CBS News online at http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/08/26/world/main798423.shtml, emphasis added.

[7] There are three main types of theories on the image of God: substantive, functional and relational. I do not see how any of these theories support the intrinsic incompatibility between the image of God and common descent.

[8] Interestingly, respected historians Adrian Desmond and James Moore argue that one reason Darwin set forth his evolutionary views was moral: he saw common ancestry as the basis to argue for abolition of slavery. See Darwin’s Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin’s Views on Human Evolution (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009).

[9] See Lamoureux, Evolutionary Creation, chapters 4-7.

The post Ain’t Gonna Make a Monkey Out of Me! Is Darwinism Compatible with Human Dignity? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 4, 2018

Should we be (most) certain that God exists?

Today this tweet from Douglas Axe (director of Biologic Institute who tweets here) caught my attention:

Since we humans always have to settle for something short of absolute proof, I'm not sure we have to qualify our certainty of God's existence in this way. We can be as confident of his existence as we can be about anything. https://t.co/6ojmKCXENN

— Douglas Axe (@DougAxe) April 4, 2018

Axe was responding in turn to this tweet from Alister McGrath:

“God’s existence may not be proved, in the hard rationalist sense of the word. Yet it can be affirmed w/ complete sincerity that belief in God is eminently reasonable & makes more sense of what we see in the world, discern in history & experience in our lives than its alternatives.”

I was interested in Axe’s claim that “We can be as confident of [God’s] existence as we can be about anything.” So I offered a reply and from there a short exchange ensued. What follows is the text of our exchange which has been converted from the cumbersome form of tweets to something resembling a conversation.

DA: “Since we humans always have to settle for something short of absolute proof, I’m not sure we have to qualify our certainty of God’s existence in this way. We can be as confident of his existence as we can be about anything.”

RR: “Not for me. I’m more sure that I exist than that God exists.”

DA: “We naturally start with greater confidence that we exist, but for this impression that we exist to be reliable, there must be a basis for rationality, and apart from God there doesn’t seem to be one.”

RR: “A conclusion is only as strong as its premises. I hope we agree that ‘I exist,’ where ‘I’ is indexed to a particular speaker, is an axiomatic premise for that speaker. Are your premises to support the conclusion that God is the sole basis for rationality at least that strong?”

DA: “The fact that we have no choice but to assume we exist and are equipped to think doesn’t make this assumption strong in the sense of being well supported. Having made the assumption (because we have to), the question is: What would have to be true for it to be justified?”

RR: “You seem to be claiming that ‘I exist’ is only pragmatically justified but not epistemically justified. If you are claiming that, my question is, on what basis do you claim that? If you aren’t claiming that, can you rephrase?”

That’s the end of our conversation to this point. If Axe replies, I’ll add that below. In the interim, I’ll simply note my view. As I see it, “I exist” (not to mention the more modest “I seem to exist” and “Either I exist or I don’t exist”) are more epistemically compelling than any non-trivial claim about God’s existence or the reliability of our cognitive faculties due to God’s existence. And I think it is simply mistaken piety and/or apologetic bravado when Christians like Axe insist that belief in God is at least as compelling as any other belief we might have.

(Footnote: In chapter 1 of my 2009 book Theology in Search of Foundations (Oxford University Press) I offer an extended critique of classical foundationalist attempts to secure maximal certainty for beliefs about God.)

The post Should we be (most) certain that God exists? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 3, 2018

God, deliver us from skepticism! (Then again, maybe not.)

The other day somebody on Twitter asked me how I manage to write so many articles. My response included noting the many sources of inspiration … like Twitter. As a case in point, consider this tweet that Michael Brown posted yesterday:

When a reliable, trusted friend shares with you how God has worked a miracle on their behalf, is your first response to question them rather than rejoice with them? God deliver us from skepticism!

— Dr. Michael L. Brown (@DrMichaelLBrown) April 3, 2018

When I read that, I knew I needed to offer a reply. My initial reply was a quick tweet:

“Whoa, Michael, are we not called to be good Bereans? Do we not give greater glory to God when we are careful about the details and seek corroborating evidence?”

While that captures the gist of my response, I decided to write an article to unpack my concern.

To begin with, when Michael refers to cases where God “worked a miracle” I assume he means substantial cases of divine intervention that preclude explication by natural causes alone such as a seemingly supernatural healing from cancer. This is important because people use the word “miracle” in many ways, including relatively mundane bits of good fortune (e.g. “I found a great parking spot at the mall on Saturday! That’s a miracle!”) and substantial providential blessings which do not necessarily exclude natural causal explication (e.g. “Our son was admitted to Harvard on a full scholarship! It’s a miracle!”). I take it that Michael is not referring to those types of cases.

To sum up, the miracle claim focuses on substantial cases of divine intervention that preclude explication by natural causes. These definitely are noteworthy claims. So how should we respond?

It is important to note that Michael stipulates the testimony of a miracle comes from “a reliable, trusted friend”. So we’re not talking about some fellow you never met before who runs up to you at a Benny Hinn rally and tells you God just gave him a gold filling in his molar. You’d surely be right to be skeptical of that claim. In our case, we’re talking about a person that we know personally and who has been proven as a reliable and trusted friend (and thus, witness). In that case, Michael is advising that we ought to accept their claim to a substantial case of divine intervention and we should not express skepticism.

I am generally sympathetic with Michael’s point. If we are Christians then we believe that God can perform miracles (as defined) and if we trust our friend then we have a good prima facie reason to trust their specific miracle claim.

But that doesn’t mean there is anything wrong with questioning. On the contrary, when a person makes a miracle claim (as defined) we should question them. We question not because we doubt God’s ability to perform miracles. Rather, we question for the following two reasons:

First, while our friends may be generally reliable, the fact remains that they are also fallible human beings. Given that fact, it is perfectly sensible to undertake some preliminary questioning of their claim, all the more so if that claim is on some highly emotional or subjective topic. And here’s the key: if this person really is a good friend, they should not be offended by a friend who takes their story with enough seriousness to seek corroborating evidence for it.

Second, insofar as God is indeed engaging in substantial cases of divine intervention that preclude explication by natural causes alone, we should want those actions carefully documented with corroborative evidence so that that evidence can give glory back to God; conversely, if the supporting evidence does not exist, we should be very diligent about falsely attributing instances of divine action to God that he did not in fact, perform.

The post God, deliver us from skepticism! (Then again, maybe not.) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 2, 2018

A Bad Objection to Christian Universalism

Christian universalism is the view that ultimately all people will be saved by God through the atoning work of Jesus Christ. Since that salvation does not occur for all in this life, universalism proposes that it will be completed posthumously. This is where the doctrine of hell comes in: Christian universalists agree that there is a hell (in contrast to Unitarian universalists, pluralistic universalists, and others), but they view hell as restorative rather than retributive.

I am not a universalist, but I am a hopeful universalist insofar as I hope I am wrong in my assessment of universalism. In other words, I hope that the Christian universalists are right and that all people are eventually restored to God through the atoning work of Jesus Christ.

Given that I hope universalism is true, over the years I have invested some effort in dispelling misunderstandings and responding to bad objections to the view. For example, a few years ago I wrote an article titled “The Very Worst Reason to Reject Universalism.” In this article, I’d like to respond to another bad reason (if not the very worst) to reject universalism: namely, the claim that universalism violates God’s justice.

Often the objection is stated in a way that makes it clear the objector misunderstands Christian universalism. Again, the view is not that there is no hell and thus no consequence for sin. Rather, the view is that all are saved in the same manner as some. In short, if the atoning work of Christ makes it possible to save a subset of the human population in accord with God’s justice, the hopeful universalist insists that the atonement also makes it possible to save the entirety of the human population in accord with God’s justice. And they rightly hope that it does.

The Christian who reacts negatively to that prospect should read carefully the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard (Matthew 20:1-16). As the owner says to those diligent workers who are angered to discover those who joined the workday late will receive the same pay: “Don’t I have the right to do what I want with my own money? Or are you envious because I am generous?’ (Matthew 20:15)

I suspect that some Christians who are opposed to universalism just might be susceptible to the same indictment. Our place is not to begrudge God’s mercy, still less to question is justice.

The proper response of the diligent worker is to hope that the landowner does give equal pay to each person, and so to be grateful when he does. In like manner, the proper response of the disciple is to hope that God gives salvation to every wayward soul, and so to be prepared to be grateful should he indeed do so.

The post A Bad Objection to Christian Universalism appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 31, 2018

I Believe on the Third Day He Rose Again . . . but what about those who don’t?

This article is an excerpt from my 2011 book You’re not as Crazy as I Think. The book includes four chapters dedicated to understanding various groups that are commonly misunderstood by evangelicals and this excerpt is drawn from the chapter titled “Not all liberal Christians are heretics.”

This article is an excerpt from my 2011 book You’re not as Crazy as I Think. The book includes four chapters dedicated to understanding various groups that are commonly misunderstood by evangelicals and this excerpt is drawn from the chapter titled “Not all liberal Christians are heretics.”

In the passage, I attempt to understand the individual who seeks to retain Christian identity whilst rejecting the central Christian miracle: the resurrection of Jesus. And in the spirit of the book, I try to place myself into their position of radical doubt in order to see whether I too, would seek to remain a Christian under those circumstances.

When I submitted the manuscript back in 2010, the editor typed this comment into the margin: “Is this for real? This is very confusing to me on this particular issue, because God has specifically said there would be no Christian faith left w/o the resurrection.” I assume he was referring to 1 Corinthians 15:14-15:

14 And if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith. 15 More than that, we are then found to be false witnesses about God, for we have testified about God that he raised Christ from the dead.

I confess that I share this editor’s incredulity toward the professing Christian who rejects the resurrection. Or at least, part of me does. But as a result of this exercise in sympathetic reasoning, part of me has come to see that matters are far more complicated.

A few years ago, I was speaking at a convention for evangelical Christian school teachers. During the talk I noted that the doctrine of the Trinity is an essential Christian belief. Afterward, a kindly elderly lady came up to me and, after graciously thanking me for my talk, lodged just one note of disagreement: “Not all Christians are Trinitarians,” she said with a smile. After asking her a few questions I discovered that she was a Oneness Pentecostal, a group that divided from the orthodox Assemblies of God denomination in 1917 due to its conviction that Father, Son, and Spirit are not three persons but rather three manifestations of the one person God.

While speaking with this lady did not change my conviction that assent to the triunity of God is an essential mark of Christian identity, it did remind me of the difference between abstract judgments and concrete conversations. That is, it is one thing to offer a general discussion of heresy and heretics, and it is another thing entirely to speak of heresy when a little old lady is smiling back at you. As I look back, that conversation made two things clear. First, that lady had thought about the concept of God’s triunity more carefully than most orthodox Christians. And second, she evinced no noticeable signs of moral corruption. So much for tarring her with the brush of Simon Magus. Indeed, in speaking with her I was reminded of the words of that great nineteenth-century Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing (who also rejected the Trinity) when he observed: “In following this course we are not conscious of having contracted, in the least degree, the guilt of insincerity.” It certainly seemed that this elderly lady, like Channing, had rejected the doctrine of the Trinity not out of hostility toward the truth but rather in a sincere pursuit of it.

Once we develop relationships with liberals and other heretics, it can be disconcerting to discover how often their beliefs appear to be held in full sincerity. For another example, we can turn to the story of New Testament scholar Marcus Borg as relayed in his intriguing book Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. Though he was raised in a conservative Christian home, in his teen years Borg began to have doubts about the existence of God: “At the end of childhood there began a period, lasting over twenty years, in which, like many, I struggled with doubt and disbelief. All through this period I continued to think that believing was what the Christian life was all about. Yet no matter how hard I tried, I was unable to ‘do’ that, and I wondered how others could.”

It certainly seems that Borg wanted to believe. Consequently, it does not seem plausible to dismiss his doubts as rationalizations to justify rebellion against God. On the contrary, reading his words I am reminded of the man who, desperate for Jesus to heal his son, cried out, “I do believe; help me overcome my unbelief!” (Mark 9:24). Like that man, Borg seemed to be anxious to believe even as he was beset by doubts. Growing up, Borg had always believed that the Bible’s testimony was perfectly reliable. Things got worse when Borg learned in his university and seminary that New Testament scholars distinguish between the Jesus of history and the Christ of the church’s faith: in other words, Jesus the man who walked on the dusty paths of Judea two thousand years ago was different from what the church claimed. Unfortunately, that discovery deepened Borg’s crisis of faith. Increasingly he came to see the church’s creedal confessions as veils obscuring the Jesus of history rather than windows revealing him. As a result, that historical Jesus, once so familiar, began to disappear into the mists of antiquity.

The discovery that the Christ of faith was doubted by many scholars left Borg with more questions than answers and ultimately forced him to consider whether to leave the faith. After all, how could he revere a Christ that he doubted could be known? But there was another possibility: expand his conception of what it means to be a Christian in a way that would be consistent with his doubts. To opt for the latter course would mean embracing a conception of Christianity that was not so heavily dependent on the beliefs Borg found himself doubting.

For a number of years, Borg wrestled with these two possibilities until in his thirties he underwent a series of mystical encounters that confirmed for him the abiding presence of God. As a result, these experiences provided a modest foundation for his still shaky faith. In light of his continuing doubts over belief, the faith that emerged was rooted not in doctrine so much as experience and ethics. Looking back a couple decades after those experiences, Borg reflected: “Now I no longer see the Christian life as being primarily about believing. The experiences of my mid-thirties led me to realize that God is and that the central issue of the Christian life is not believing in God or believing in the Bible or believing in the Christian tradition. Rather, the Christian life is about entering into a relationship with that to which the Christian tradition points, which may be spoken of as God, the risen living Christ, or the Spirit.

Ask Borg whether he affirms the great creeds of the faith—the Apostles’ Creed and Nicene Creed, for instance—and I suspect that at best you will get a shrug of the shoulders. But rather than abandon the faith, Borg answered his doubts by expanding (or changing) the meaning of Christian so as to find a place in the church for his own praxis and experientially based faith. For Borg, the heart of Christian faith is found not in doctrinal assent but rather in a life modeled on the perfect life of Christ.

Those of us who do not struggle with Borg’s doubts and who are able to affirm a much fuller set of doctrines may be thankful for our greater confidence. But does that mean that there is no room in the church for Marcus Borg or the many similar souls that fill the pews of a St Joseph’s on a Sunday morning? If we are to take Borg’s own account seriously, we can no more doubt his sincerity than that of the elderly Oneness Pentecostal lady. Borg too seems to be nothing like the mythical Simon Magus who was maniacally opposed to the truth of the gospel. So far as I can see, he appears to want to believe even as he struggles with more doubts than most. As a result, it seems to me simply unfair to attempt to construe his struggles of faith as less than genuine. But then what is the origin of his doubts?

One possibility is to think of his doubts as a special thorn in the flesh. We all know about Paul’s thorn in the flesh, an unknown affliction that he prayed to be withdrawn. When Paul prayed to Christ that this thorn might be relieved, the reply came that Paul should instead rely on Christ’s strength (2 Corinthians 12:7-10). Many other great Christian leaders of history have suffered their own thorns in the flesh. For instance, Martin Luther struggled all his life with doubts about his salvation. In my view, Luther’s sincere struggles evince not a fault in character but rather a burden he was given to draw him back to Christ. Is it at least possible that Borg’s struggles over doctrines could likewise be his thorn in the flesh? And if this is possible, then wouldn’t the proper response to Borg’s struggles over doctrine be not anger and censure but rather sympathy and encouragement (without condescension, of course)?

Although I do not know Marcus Borg personally, I have two good reasons to think he is the genuine article. The first is the quality and integrity that comes through his writings. The second is the testimony of that towering intellectual pillar of Anglican orthodoxy, N. T. Wright. While Wright is widely lauded as one of the premier New Testament scholars in the world, he is also good friends with Borg. In the eye of many evangelicals, the problem arises not with the friendship per se but rather with the fact that Wright believes his resurrection-denying friend is also a Christian. This is how he put it in a 2006 interview: “Marcus Borg really does not believe Jesus Christ was bodily raised from the dead. But I know Marcus well: he loves Jesus and believes in him passionately.” So then why does Borg not believe? Wright suggested that “the philosophical and cultural world he has lived in has made it very, very difficult for him to believe in the bodily resurrection.” Is it possible as Wright said, that a person could be a Christian and yet reject the resurrection of Christ?

Let’s begin to address this question by turning to the Easter season. Just like clockwork, every Easter popular magazines like Time and Newsweek find a way to squeeze Jesus onto the cover, typically with a heading that carries a whiff of scandal like “How the Jesus of History Became the Christ of Faith” or “Did Jesus Really Rise?” Without fail, these articles are weighted more to hype than substance. But what if a story broke in the media about Jesus that actually had some substance to it? What if some real evidence arose questioning the resurrection of Jesus?

That scenario is addressed in Paul Maier’s novel A Skeleton in God’s Closet. In the story, well-respected archaeologist and devout Christian Jonathan Weber is working on a dig for the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea when the remains of Jesus Christ are discovered. As you might guess, with this discovery Weber finds his faith coming under severe testing. After all, if Jesus’ bones remained in the tomb then Jesus did not, in fact, rise from the dead, and this means that a doctrine that has stood at the center of Christian faith for two thousand years is false. As news of the discovery sweeps the globe, it leaves in its wake a sea of deeply confused Christians. However, Weber observes that not all Christians find their faith upended by the discovery: “A Methodist professor said he’d have to do a lot of rethinking. But an Episcopal rector said that finding Christ’s remains ‘would not affect me in the slightest.’ I recall being totally disgusted at that response. The one I easily agreed with was a Catholic New Testament professor at St. Louis University who said that he ‘would totally despair.’ Now, that was honest!”

The scenario leaves each reader to ask the same question for himself or herself. Would I be left to do a lot of rethinking like the Methodist professor? Or would I despair like the Catholic professor? And what about the Episcopalian rector whose faith never depended on the resurrection? What sort of faith is that anyway?

Let’s think about this question more carefully. If Jesus’ body were discovered we would suddenly find ourselves in Borg’s shoes (or a pair much like them), needing to decide whether to leave the faith or reinterpret it. There would be good grounds for the first move, given Paul’s declaration that “if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith” (1 Corinthians 15:14). So if Christian faith without Christ’s resurrection is useless, we might as well find something else to believe in. But what? Islam? Deism? Atheism? Amway? (Or perhaps a combination thereof?) The more I think about the radically, sweeping implications of walking away from faith altogether, of rejecting everything in Christianity lock, stock, and barrel, the more game I am to consider the second option. The point can be made by considering G. K. Chesterton’s commentary on the complex reasons why people hold Christian belief:

[I]f one asked an ordinary intelligent man, on the spur of the moment, “Why do you prefer civilization to savagery?” he would look wildly round at object after object, and would only be able to answer vaguely, “Why, there is that bookcase . . . and the coals in the coal-scuttle . . . and pianos . . . and policemen.” The whole case for civilization is that the case for it is complex. It has done so many things. But that very multiplicity of proof which ought to make reply overwhelming makes reply impossible.

According to Chesterton, in much the same way that our commitment to civilization depends on a multiplicity of factors rather than a single point, so Christian faith also rests on a multiplicity of factors. A person is typically not a Christian for one single reason but because of a whole variety of factors. For instance, they have experienced God’s providential hand guiding their life, they have found inspiration and guidance in the Scriptures, they have had great Christian mentors and models, their nephew was healed of cancer after an all night prayer meeting, and God saved their marriage. In short, they are a Christian because it provides the most complete, satisfying and plausible understanding of the human condition, where we came from and where we are going. For these reasons and many others, they could indeed resist the attempt to throw all this away on the condition that one doctrine should come up false, even if it is a doctrine as central as the bodily resurrection of Christ.

And so, when the alternative of rejecting faith is considered, it might seem preferable to retain our Christian faith, even given the discovery of Jesus’ body. But is this really a serious possibility? Or would keeping faith under these conditions be like keeping the marriage going after you discover your spouse is a bigamist? That is, as great as all these other things may be, without a resurrection of Christ is there really anything left to save? While I appreciate the reservation here, I think we need to understand the real force of the civilization parallel. To push things further, consider a specific example. I know a missionary who was home on furlough raising ministry support and had come up short $300 a month. Just when he was about to give up, having exhausted every possible avenue of support, he received a call from somebody who felt God laying on his heart the need to support him . . . at $300 a month. (At this time nobody except the missionary’s wife knew of their specific financial need.) I refer to an event like this as a “LAMP” which is an acronym for “little amazing moments of providence.” Many Christians have experienced LAMPs like this in their life. Is it so obvious that the discovery of the body of Jesus would persuade people to dismiss all these LAMPs as mere happenstance? Would they really be forced to reject Christianity, kit and kaboodle, as plain false?

As A Skeleton in God’s Closet unfolds, Jonathan Weber wrestles with this question: should he surrender his Christian faith altogether, or could he instead adopt a faith like that of the Episcopalian rector?

[M]aybe Mark Twain was right, Jon finally had to admit to himself. And not only Twain, but all of liberal theology, which had been denying a physical resurrection of Jesus ever since David Strauss and Ernst Renan did so in nineteenth-century Germany and France. Yes, maybe all the higher critics, particularly Rudolf Bultmann, were right all along. The Resurrection never happened, but it was the faith and belief that it did that was important. And all his conservative, Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod Sunday school and Bible classes, and all the endless sermons . . . wrong!

As unsettling as the thought is, we ought to reflect on Weber’s questions. So I ask myself, if Jesus’ body were discovered would I leave the Christian faith altogether, or would I instead adopt a more liberal interpretation of that faith?

Try as I might I cannot be sure which of these options I would follow. The dilemma recalls the crisis that lies at the center of William Styron’s novel Sophie’s Choice where we meet sweet and brooding young Sophie, a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps. As the novel unfolds we discover that Sophie was forced by a cruel Nazi to choose which one of her two children would live and which would die. How could any parent be asked to make such an unthinkable choice? The popularity of the book and subsequent film (starring Meryl Streep) led to the popularization of the term “Sophie’s choice” as a way to refer to any impossible or unthinkable decision. It seems to me that where the Christian faith is concerned, the discovery of Jesus’ remains would pose just such a crisis of decision. Do I reject the faith altogether or do I set aside the centrality of the historic resurrection? It strikes me that this is by no means a straightforward or easy choice. And if it seems presumptuous to judge Sophie for making such a forced decision, it seems also presumptuous to judge a liberal Christian for having made a theological judgment under equally impossible circumstances.

For a discussion of this oneness view of the Trinity, often called modalism, see my Finding God in the Shack (Colorado Springs, CO: Paternoster, 2009), 51-53.

Cited in Gary J. Dorrien, The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 25.

Borg, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time: The Historical Jesus and the Heart of Contemporary Faith (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1994), 17.

Borg, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time, 17.

The fact that some liberal Christians would repudiate this analysis is not especially relevant, for it would still remain possible that others might suffer from a thorn of doctrinal doubt.

Heresy undoubtedly has served a valuable function in the church, and we wonder how often God might have allowed a heretic’s mistake as a foil to spur the wider church on to greater doctrinal clarity and fidelity. For a suggestive discussion see Alister McGrath, Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth (New York: HarperOne, 2009).

Borg and Wright explored their differences in The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperOne, 2007).

See the interview with Jill Rowbotham: “Resurrecting Faith,” The Australian (April 13, 2006), available at http://www.virtueonline.org/portal/mo....

Paul Maier, A Skeleton in God’s Closet (Nashville, TN: Westbow, 1994), 258.

Chesterton, Orthodoxy (1908; Reprint: London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1996), 119.

Maier, A Skeleton in God’s Closet, 200.

The post I Believe on the Third Day He Rose Again . . . but what about those who don’t? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 28, 2018

Here I Stand: On Alvin Plantinga’s Luther Moment

I took a course with Alvin Plantinga in 1998 (wow, twenty years ago!). The main textbook was an early draft of his book Warranted Christian Belief. By the time the book was published two years later, I was well into my PhD thesis in England in which I was seeking to articulate a fundamental theology informed by Plantinga’s epistemology.

I took a course with Alvin Plantinga in 1998 (wow, twenty years ago!). The main textbook was an early draft of his book Warranted Christian Belief. By the time the book was published two years later, I was well into my PhD thesis in England in which I was seeking to articulate a fundamental theology informed by Plantinga’s epistemology.

Suffice it to say, Warranted Christian Belief formed a big part of my intellectual formation. It’s a sprawling book of close to 500 pages, enlivened throughout by Plantinga’s eclectic interests, penchant for incisive thought experiments, and dry but razor-sharp wit.

What does a five hundred page defense of the intellectual credibility of Christianity look like? In one sense, it looks surprisingly deflationary. But for all that it gives up in ambition, it gains in spades in terms of intellectual credibility. At one pivotal moment Plantinga stands shoulder to shoulder with Martin Luther to thrown down the existential gauntlet. And it looks like this:

I believe a thousand things, and many of them are things others – others of great acuity and seriousness – do not believe. Indeed, many of the beliefs that mean the most to me are of that sort. I realize I can be seriously, dreadfully, fatally wrong, and wrong about what it is enormously important to be right. That is simply the human condition: my response must be finally,

“Here I stand; this is the way the world looks to me.”

The beauty of that statement is that it represents the delightfully nuanced, humble, and existentially self-aware conclusion of more than a thousand rigorously argued pages. (A thousand? Yes, you see, Warranted Christian Belief was the final installment of a triumvirate that presents a cumulative epistemological argument.)

But here’s the thing. I would much rather inhabit a humble square of epistemic rationality and warrant which is sustained by rigorous arguments than to claim the universe on woolly and ill-begotten ambition.

For that, I say thanks, Alvin Plantinga.

The post Here I Stand: On Alvin Plantinga’s Luther Moment appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 27, 2018

Depersonalizing the Damned: Hell and the humanity of those who go there

Let’s return to a discussion of the doctrine of hell and in particular, the concept of hell as eternal conscious torment. According to this concept, to end up in hell is to end up in a state of eternal alienation from God, one which results in unimaginable physical and spiritual/psychological torment. And that torment never ends.

The inevitable question arises: how can God possibly allow a state of affairs so awful, so unimaginably terrible as this?

If you don’t yet resonate with the force of the question, perhaps we can personalize it. Suppose that the damned wretch of which we speak is your own son or daughter. Can you imagine a heaven which exists concurrent with your beloved child suffering unimaginable physical and spiritual/psychological torment forever?

No doubt, many people will reply that they cannot envision such a scenario, even as a remote possibility. How could anyone possibly be reconciled to God in Christ, how could they exist in a state of affairs where there are no more tears (Rev. 21:4), and how could they do so at the very same time that their beloved child is suffering maximally in body and mind in hell?

C.S. Lewis felt the sting of this problem. And in The Great Divorce he sought to provide an answer. In that answer, Lewis opted to dehumanize and depersonalize the damnable wretches that end up suffering forever. This is how he put it:

“Hell begins with a grumbling mood, always complaining, always blaming others … but you are still distinct from it. You may even criticize it in yourself and wish you could stop it. But there may come a day when you can no longer. Then there will be no you left to criticize the mood or even to enjoy it, but just the grumble itself, going on forever like a machine.”

This is a very frustrating passage insofar as it aspires to have its rhetorical cake and eat it too. On the one hand, Lewis suggests that we need not suffer forever with our damned loved ones because at some point “there will be no you left…” On the other hand, he never endorses annihilationism, the claim that human beings are destroyed in the process of damnation. And that leaves one with the impression that in some sense the damnable wretch does exist forever, although not as “you”.

But if it isn’t “you” then who is the individual that is suffering … and why are they suffering for the sins and errors that you committed Assuming that annihilation is off the table, what would it mean to say that the “grumble” goes “on forever like a machine”? So far as I can see, it can only mean that the individual continues to exist and to suffer. However, that individual has been depersonalized as a “grumble,” presumably as a way to reconcile that unimaginably horrific fate with the redeemed parent who is now expected to experience inexpressible joy in heaven.

And this, I would insist, is horrible. No doctrine of hell should be sustained by depersonalizing the damned children of the redeemed as “grumbles”. The conclusion: either embrace the conclusion that your beloved child may eventually suffer unimaginable torment eternally, and that this horrific eventuality is consistent with the world-redeeming goodness of Christianity, or reject the doctrine of eternal conscious torment outright as an intolerable error.

The post Depersonalizing the Damned: Hell and the humanity of those who go there appeared first on Randal Rauser.

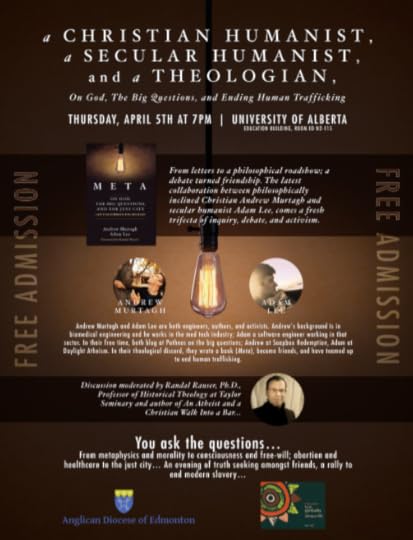

A Debate on God in Edmonton

Check out this upcoming evening of discussion and debate hosted by yours truly (that’s a fancy-schmancy means of self-reference).

The post A Debate on God in Edmonton appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 25, 2018

Is the Exodus as important to Christian belief as Jesus’ resurrection?

When I was growing up, I learned to read biblical narratives as historically reliable accounts of past events. Whether the issue was the death and resurrection of Jesus, the curious maritime journey of Jonah, the Exodus from Egypt, Samson’s killing a thousand men with the jawbone of an ass, or Adam and Eve talking to a serpent in the Garden of Eden, all these stories were accepted with equal conviction as accurate accounts of past events.

Then I went to university and that “historicity assumption” began to be eroded. The erosion began with the details. For example, Exodus 12:37-38 describes the Israelite Exodus as “about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides women and children.” Altogether, the total number would have been close to two million people. But there is no archaeological evidence in ancient Egypt for a demographic shift on this extraordinary scale.

Next, there was the matter of dating texts. For example, while I was raised to believe Moses wrote the Torah, I soon discovered that scholars believe the Torah reached final form around the time of the Exile, perhaps eight hundred years after the Exodus. To be sure, these texts would have been based on earlier writings and abundant oral tradition. Nonetheless, the question needs to be asked: how reliable should we consider an eight-hundred-year transmission process?

Third, there were the scientific considerations. This factor was most obvious when it came to the familiar bedrock narratives of Genesis beginning with Adam and Eve in the Garden. How would one reconcile these narratives with the scientific account of earth history? And what about Noah and the global flood? On that point, I soon discovered scholars who insisted that the flood was local. And other scholars attempted to reconcile Adam and Eve with a dizzyingly old earth by suggesting they lived perhaps fifty thousand years ago. But were these narratives, now reread in such a way as to correspond to scientific data, still the same stories? Or had well-intentioned revisions turned them into something different altogether?

Finally, my historicity assumptions were challenged by literary considerations. The sharpest challenge came with isolated stories like Job and Jonah and Esther. Was there a Job at all? Or was this writing simply a profound poetic-literary exploration of the enduring problem of evil and suffering? Did it miss the point altogether to insist that Job must be a historical person for the book of Job to have authority as an inspired text?

With all that in mind, I recently posted a survey on the historicity question. Here are the results:

Do you think that Christians should believe in ancient Israelite miracles like the Exodus from Egypt and Elijah's miracles with the same degree of conviction as the resurrection of Jesus? Or should apportion our belief to the relative doctrinal importance and historical evidence?

— Randal Rauser (@RandalRauser) March 15, 2018

At this point, I count myself firmly with that 66%. I believe that there are excellent historical (and theological) reasons to accept the atoning death and historical resurrection of Jesus. But that same degree of historical evidence and theological importance does not apply to many other narratives in Scripture. To put it bluntly, who can seriously insist that Samson’s killing of a thousand men with the jawbone of an ass is as well attested historically and as theologically central as the atoning death and resurrection of Jesus? And if we agree that it isn’t, then why not apportion our belief in various narratives to their theological importance and supporting evidence?

The post Is the Exodus as important to Christian belief as Jesus’ resurrection? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 24, 2018

What kind of diversity do you value most?

I’d like to return to the themes of diversity and affirmative action that I wrote about a couple weeks ago. So imagine a small seminary in North America with a faculty that consists of five Caucasian males who were all born and raised in North America. The seminary posts an announcement for a new faculty position and the ad includes the statement “We especially welcome applications from women and visible minorities.”

Twenty candidates apply for the position. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that all are strong candidates in terms of education, publications, and teaching experience. But while seventeen of them are Caucasian males born and raised in North America, three bring some degree of diversity.

The first diversity candidate is Susanne, a Caucasian female born and raised in North America. The second candidate is Jin, a Korean male born and raised in Seoul, Korea. The final candidate is Mark. While Mark is a Caucasian male (and thus not a visible minority), he does bring a wealth of cultural and experiential diversity since he was raised in Tanzania and Thailand, he speaks fluent Swahili and Thai, and he is at home in both East African and South-East Asian cultures.

Each of these individuals brings a valuable diversity to an ethnically homogeneous, monocultural faculty. Assuming that these three candidates are otherwise equal, how would you prioritize the diversity each might bring to the institution? Do you prioritize the visibility of the diversity that Susanne and Jin bring? If so, do you prioritize gender diversity or cultural and linguistic diversity? Or do you view the visibility of diversity as a secondary issue which might be trumped by Mark’s diverse transcultural experience?

The post What kind of diversity do you value most? appeared first on Randal Rauser.