Nancy Moser's Blog, page 12

December 13, 2010

Syllabub at Belle Meade

Past this stone wall (how old is it? who built it? did slaves labor create it?, a long drive carries you towards a house in the distance that's reminiscent of Tara. Of course you're only a visitor and it's 2010, so you won't be approaching the house from this angle. Instead, you'll drive around to the side of the house, park, buy a ticket, and pass through the gift shop and by a restaurant and back outside where you encounter barn and carriage house, smokehouse, and doll house until ... finally ... you join other guests and wait. You look towards the road, trying to imagine what it must have been like to live here in the days when Belle Meade was a working horse farm five thousand acres large.

Past this stone wall (how old is it? who built it? did slaves labor create it?, a long drive carries you towards a house in the distance that's reminiscent of Tara. Of course you're only a visitor and it's 2010, so you won't be approaching the house from this angle. Instead, you'll drive around to the side of the house, park, buy a ticket, and pass through the gift shop and by a restaurant and back outside where you encounter barn and carriage house, smokehouse, and doll house until ... finally ... you join other guests and wait. You look towards the road, trying to imagine what it must have been like to live here in the days when Belle Meade was a working horse farm five thousand acres large. Railroad tracks brought buyers and mares, and took yearlings to the big spring sale. Today, however, Belle Meade sits atop a hill in the middle of the greater Nashville area. In fact, it wouldn't be hard to drive right by without a glance. Turn back towards the house, and a docent dressed in period dress helps your imagination carry you back in time. She has an authentic and delightful southern accent and she adores history ... and you can tell.

Railroad tracks brought buyers and mares, and took yearlings to the big spring sale. Today, however, Belle Meade sits atop a hill in the middle of the greater Nashville area. In fact, it wouldn't be hard to drive right by without a glance. Turn back towards the house, and a docent dressed in period dress helps your imagination carry you back in time. She has an authentic and delightful southern accent and she adores history ... and you can tell. The women of Belle Meade are, like the women of many historic sites, hard to find at first. I don't have a portrait of the woman I'd like to show you today, but her photograph is atop a sideboard in the main hall of this great house. She wears a wide white collar that comes to a point in the front, and the docent explains that, were you coming to visit back in the day, this African American woman would open the door and greet you before guiding you into whichever of the four rooms on the main floor were appropriate. That would, of course, depend on your station in life and who you were here to see. Were I transported back in time, I wouldn't have dared come to the front door of this place. I don't know where I would have been at Belle Meade, since my skin is white ... but my people were poor.

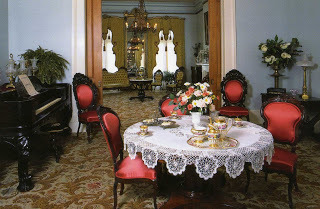

I try to imagine what it would have been like to spend time in these parlors ... but I can't. I have to admit, the finery makes me want to bolt.The people who graced these rooms would have been horrified by my lack of ... just about everything. I would have needed to spend a lot of time with the book I bought in the gift shop titled Fashionable Dancer's Casket or the Ball Room Instructor a new and splendid work on Dancing, Etiquette, Deportment and the Toilet.

I try to imagine what it would have been like to spend time in these parlors ... but I can't. I have to admit, the finery makes me want to bolt.The people who graced these rooms would have been horrified by my lack of ... just about everything. I would have needed to spend a lot of time with the book I bought in the gift shop titled Fashionable Dancer's Casket or the Ball Room Instructor a new and splendid work on Dancing, Etiquette, Deportment and the Toilet.

"In the selection of colors," the book advises, "a lady must consider her figure and her complexion. If slender and sylph-like, white or very light colors are generally supposed to be suitable; but if inclined to embonpoint (that would be me), they should be avoided, as they have the reputation of apparently adding to the bulk of the wearer." Some things never change. Women had to be concerned with their figures back then, too.

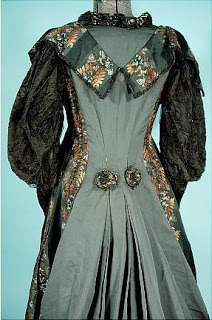

Up the sweeping staircase to the guest rooms (the family had a separate wing), you can imagine the ladies here, because mannequins have been dressed in period costume. Such tiny waists ... how did they breathe? Such elegance. Did they ever let their hair down and just relax? I can almost see Scarlett O'Hara clinging to one of these bed posts and ordering the woman who's picture I just saw in the downstairs hall to lace her up.

Well ... once laced up, I imagine the ladies had no trouble at all finding great satisfaction in a tablespoon or so of the syllabub waiting in the parlor downstairs. I thought I'd close the blog with a recipe from Amelia Simmons, an American orphan (yes, she had that on the book) who wrote, American Cookery: or, the art of dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables, and the best modes of making Puff-Pastes, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards, and Preserves, and all kinds of CAKES, From the Imperial PLUMB to plain CAKE. Adapted to this country, and all grades of life. (WHEW ... now THERE's a title!)

To make a fine Syllabub from the Cow.

Sweeten a quart of cyder with double refined sugar, grate nutmeg into it, then milk your cow into your liquor, when you have thus added what quantity of milk you think proper, pour half a pint or more, in proportion to the quantity of syllabub you make, of the sweetest cream you can get all over it.

Let me know how it tastes................................and bon appetit!

--Stephanie G.

December 9, 2010

The Square Root of Something is Nothing

Society women of the 19th century wanted to be known for their talents in the arts, not for their smarts. Most didn't go to school, but were taught the basics of reading, 'riting, and 'rithmatic by their governess or perhaps a hired tutor. As women, it was more important they were adept at playing piano, singing, doing embroidery, or painting. Adept, but not too good at it. To excel, or heaven forbid, to try to earn money with one's talent, was forbidden.

Society women of the 19th century wanted to be known for their talents in the arts, not for their smarts. Most didn't go to school, but were taught the basics of reading, 'riting, and 'rithmatic by their governess or perhaps a hired tutor. As women, it was more important they were adept at playing piano, singing, doing embroidery, or painting. Adept, but not too good at it. To excel, or heaven forbid, to try to earn money with one's talent, was forbidden. Fine. I can accept that. Until I start to put myself in their shoes. I've always been good at math. How would I have fared back then? Would I have been allowed to use my math-gift? I think of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind. She was able to add a column of numbers in her head—which came in handy when she took over her husband's general store and started a lumber mill. But she was the exception. And face it, she wasn't real.

Fine. I can accept that. Until I start to put myself in their shoes. I've always been good at math. How would I have fared back then? Would I have been allowed to use my math-gift? I think of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind. She was able to add a column of numbers in her head—which came in handy when she took over her husband's general store and started a lumber mill. But she was the exception. And face it, she wasn't real. Being good at math . . . would I have even known I was good at it? I think that's the saddest part about women of history. What gifts were left undiscovered? How many female mathematicians, scientists, or engineers went through their lives having no inkling of their natural strengths?

Marie Curie observing uranium

Marie Curie observing uraniumOf course there are the exceptions: Madame Curie (physicist & chemist who studied radioactivity, and won two Nobel prizes), Elizabeth Blackwell (first female doctor in the USA), Emily Roebling (engineer on the Brooklyn Bridge). But what about the women of the middle class, or even women from the poorest classes? Those who had to work for a living might have had a chance to utilize their practical gifts, but they probably didn't have the chance to know if they were good at those talents so cherished by the upper classes: singing, playing piano, embroidering, or painting. So who had it best in this regard?

Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth BlackwellI haven't a clue.

The theme of all my novels is constant: we each have a unique purpose—the trick is to find out what it is. Because this desire-to-know is so ingrained in me, I feel extra pain in knowing so many women through the ages have not fulfilled their potential.

Emily Roebling

Emily RoeblingAnd yet who of us have? What we can learn from these women who were subjected to stifling rules, is that we—who have no such rules--have no excuse for not making a concerted effort to discover all our gifts and talents, and to use them to make some kind of difference in the world.

So stop right now. Make a list of what you know you're good at, what you think you might be good at, and what would be your dream "gift". Take an accounting of all that you are—and can be. Then use your gifts to the fullest.

Do it for all the women who've gone before.//Nancy

December 6, 2010

Women and the Battle of Franklin

There is no portrait of a lady to share this week. The women who herded their children down these stairs while a fierce battle waged around them are barely mentioned in this place. They are, as I said last week, more of a footnote to the story of the Battle of Franklin, wherein eighteen thousand mostly barefoot and starving Confederate soldiers engaged the Federal army.Hay bales literally yards from this back door mark the line of battle, but the battle doesn't stop at those hay bales. It surges past it until

There is no portrait of a lady to share this week. The women who herded their children down these stairs while a fierce battle waged around them are barely mentioned in this place. They are, as I said last week, more of a footnote to the story of the Battle of Franklin, wherein eighteen thousand mostly barefoot and starving Confederate soldiers engaged the Federal army.Hay bales literally yards from this back door mark the line of battle, but the battle doesn't stop at those hay bales. It surges past it until men fight in the yard while sisters and mothers and children huddle in a stone-lined basement room, and two non-combatants do their best to keep soldiers in search of respite from breaking in.

men fight in the yard while sisters and mothers and children huddle in a stone-lined basement room, and two non-combatants do their best to keep soldiers in search of respite from breaking in. One of the men in that basement room, Moscow Carter, has already been a prisoner of war. His wife is dead and he has signed the oath of allegiance to the union so he can get home to help care for his four children. Moscow's father, Fountain Branch, is also a widower. When Fountain Branch and his wife Polly moved into this lovely

brick home, it was at the edge of town on Columbia Pike, the main road to Nashville. It takes more than a little effort to imagine farmland and isolation today, as our tour guide tells us that the cotton gin was across the two-lane paved road near the Dominos Pizza.

brick home, it was at the edge of town on Columbia Pike, the main road to Nashville. It takes more than a little effort to imagine farmland and isolation today, as our tour guide tells us that the cotton gin was across the two-lane paved road near the Dominos Pizza.But in the basement, with the saw-marks still evident on the undersides of the floorboards above your head and the faint aroma of "basement," it gets easier to imagine the four women living here in what must have sounded like hell.

One woman, Fountain Branch's daughter-in-law, has come north from Mississippi with her two children … to be safer. What must she be thinking as she huddles in the basement? Can she hear the bullets peppering the side of the house? Can she hear the screams?

When the battle is over, Squire Carter and his two daughters light lanterns and go looking for their brother, Todd. He's been off at war for a long while; a courier and aide to one of the generals fighting here. He's out there … somewhere. They find him, only 175 yar

ds from the house. He's been lying on the battlefield through the long, frigid night. While an 8-year-old and an 11-year-old hold lanterns, a doctor operates on Todd's head wound and moves on to others. He will use the parlor for a surgical theatre. Forty hours later, resting in the room pictured on the right. wounded in what was left of the family's vegetable garden, Todd will die just a few yards from the room where he was born.

In two days, when the Confederate army leaves the area for Nashville and another ill-fated battle, the women of Franklin will be called on to nurse the wounded left behind. Thousands of wounded. The nurse's photographs do not hang on the walls of the Carter House museum alongside those of the men they cared for. [Photos aren't allowed there.]

The women of Franklin remain mostly nameless, represented in the museum only by an ammunitions chest that Moscow Carter found on the battlefield and the family (presumably the women) later used "to hold quilts," and in the fine running stitches that hold white stars on the blue ground of a hand-pieced flag "presented to the men of Company D, First Tennessee Regiment … by the ladies of Franklin."

Who were they? What were they names? What did they look like? How did they feel about … anything?

The museum doesn't tell us. The tour guide doesn't say. And the walls of Carter House keep those secrets.

December 2, 2010

The Mrs. Astor

I've been talking about high society in New York City during the Gilded Age (the last few decades of the 1800's.) The head of that elite group was Caroline Astor. The Mrs. Astor. How did she gain this role? She took it. She created it.

I've been talking about high society in New York City during the Gilded Age (the last few decades of the 1800's.) The head of that elite group was Caroline Astor. The Mrs. Astor. How did she gain this role? She took it. She created it.

In 1892, she and a party-planner named Ward McAllister (see Mr. Society blog) joined forces and created "The Four Hundred" (see The Four Hundred blog.) Mrs. Astor and Ward McAllister met twenty years earlier, in 1872, when they were both in their forties. She was from a founding family (the Schermerhorns) and had married into the wealthy Astor family. McAllister was a man who'd made his reputation as an expert in etiquette and entertaining. In the 1890's, they linked arms and stepped forward, intent on creating something special in New York society—in creating it their way. McAllister said, "If you want to be fashionable, be always in the company of fashionable people." It didn't matter if you liked them, only that they held a position that increased your position. And yet, beyond McAllister's influence, the bottom line was that women ran society. Europeans were often amazed at how American men relinquished this control. And the women of society accepted McAllister as their advisor, while their men only tolerated him.

One of Mrs. Astor's gowns

One of Mrs. Astor's gowns that was auctioned offMcAllister adored the attention. But as willing as he was to be in the limelight, Mrs. Astor was far more regal and stately in her way of presenting herself. She never talked to the press, often wore a veil when she went out during the day, hated to be photographed, and never even acknowledged that list existed—though she used it for her own party giving. She gave lavish parties, and yet her four-story brownstone at 350 Fifth Avenue never changed. If the upholstery or drapes got worn, she simply had them replaced with exactly the same fabrics. Talk about a woman set in her ways! Or maybe she simply knew what she liked.

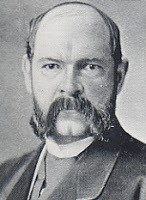

William B. Astor

William B. AstorIn 1834 Caroline had married William Blackhouse Astor, but after having five children, she and her husband virtually led separate lives. William preferred to spend his time on their yacht, and wanted little to do with the society his wife helped mold. Mrs. Astor often went to parties on the arm of McAllister. Yet in pursuit of her own image, she insisted her husband drop the "Blackhouse" part of his name, and insisted she be called, simply, Mrs. Astor. It was as if she was the only Mrs. Astor, and more than that, that she was the wife of the eldest Astor heir (which she wasn't.) Luckily, her sister-in-law, Charlotte didn't mind (Charlotte was married to the heir, John Jacob Astor III). When Charlotte died in 1887, Caroline continued using her title of the Mrs. Astor, but Charlotte and John J's only son, William Waldorf Astor, insisted that his wife should be called "Mrs. Astor". He and "Aunt Lina" feuded over this and other things. To get back at her, he tore down his father's house (which was next door to Aunt Lina's house at 350 Fifth Avenue) and built the original Waldorf hotel abutting her brownstone (now, In the location of her house and the hotel, stands the Empire State Building.) Yet no matter what the nephew did to provoke his Aunt Lina, Caroline continued to hold society's crown. She seems like a very pragmatic, never-gets-ruffled type of woman. The nephew did get ruffled, and eventually retreated to Great Britain where he became a viscount.

Alva Vanderbilt in costume

Alva Vanderbilt in costume forher 1883 ball

But even before "the Four Hundred" came into being, Caroline flexed her muscles. Back in the early 1880's there was an up and coming family in New York City society: the Vanderbilts. With her own NYC roots going back centuries, Caroline looked down at the Vanderbilts as "new money". She wanted little to do with their matriarch, Alva Vanderbilt. But in 1883 Caroline was backed into a corner and was forced to accept Alva into the inner circle. Alva was giving a huge costume ball. Caroline's daughter Carrie and her friends had been practicing a new dance, a Star Quadrille. They were excited about dancing it at the ball. But then Mrs. Vanderbilt informed Mrs. Astor that Carrie could not attend because Caroline Astor had never formally called on Alva. To appease her daughter, Caroline sent Alva her card, and Carrie went to the ball. This opened the door of society to the Vanderbilts—and they never retreated.

John J. Astor IV and son Vincent

John J. Astor IV and son Vincent After her husband's death in 1892, Caroline moved in with her only son, John Jacob Astor IV, and his wife. As a sad aside, this son went down with the Titanic. Luckily, Caroline was spared suffering from that tragedy, as she had died in 1908, four years before the Titanic went down. Yet I can't help but imagine what it would have been like if the Mrs. Astor had been on that ill-fated voyage. The ship wouldn't have dared to sink.//Nancy Moser