Nancy Moser's Blog, page 10

April 14, 2011

The Breakers

Summer "cottage" my foot. Yet that's what the wealthy set of the Gilded Age called their mega-mansions in Newport.

Summer "cottage" my foot. Yet that's what the wealthy set of the Gilded Age called their mega-mansions in Newport.The Breakers is the largest of these mansions and is used in the climax of my novel An Unlikely Suitor. Encompassing 65,000 square feet of living space (not to mention the cubic feet) it's the size of thirty homes in one—and one family lived in it. A little about them:

Cornelius Vanderbilt II

Cornelius Vanderbilt IIby John Singer Sargent

Cornelius Vanderbilt II was the grandson of the Commodore who ignited the Vanderbilt fortune decades earlier by getting into steamships and railroads. Cornelius was the favorite grandson and was bequeathed $5 million upon his grandfather's death in 1877. When his father (William Henry) died in 1885, he received $70 million. Quite the nest egg. But C-2 didn't sit around doing nothing. He took over the helm of the his family's railroad legacy.

But backing up…C-2 met his wife Alice Gwynne while they were teaching Sunday school. They married in 1867 and had four sons and three daughters. Mrs. Vanderbilt was a leader in New York Society. Here's a picture of her at one of her costume balls in 1883, dressed as "Electric Light".

This portion of the Vanderbilt family was very generous and gave to many charities including the YMCA, Salvation Army, Red Cross, their churches, as well as donating Vanderbilt Hall at Yale in memory of their son William, who died of typhus while in his junior year there in 1892. I think it's important to note that when C-2 died he had not added to his fortune, but had given away what he had made over his lifetime. We're talking millions.

Breakers 1909

Breakers 1909 When they built the Breakers they had five living children, aged 9, 15,18, 20, and 22. The first Breakers burned to the ground in 1892. Its replacement was started a year later, and finished the year of my novel, 1895. But Mr. Vanderbilt suffered a bad stroke the following year, so this was the only year the Breakers was fully enjoyed by Alice and Cornelius. The 70-room mansion purportedly cost $7-12 million to build ($150-260 million in today's dollars.)

Alice and daughter Gertrude Because the first house had burned down (as did many houses in the Gilded Age due to the use of open flame lighting and fireplaces) C-2 was determined the new house not suffer the same fate. And so he built the house without the use of wood. It used steel trusses, and C-2 even had the furnace placed away from the house, under the street. Set on 13 acres, commanding a view of the sea, the Breakers represents the epitome of Gilded Age extravagance with Italian and African marble.

Alice and daughter Gertrude Because the first house had burned down (as did many houses in the Gilded Age due to the use of open flame lighting and fireplaces) C-2 was determined the new house not suffer the same fate. And so he built the house without the use of wood. It used steel trusses, and C-2 even had the furnace placed away from the house, under the street. Set on 13 acres, commanding a view of the sea, the Breakers represents the epitome of Gilded Age extravagance with Italian and African marble. Dining RoomThe Music Room is decorated in real gold, and the Dining Room has columns of alabaster. Richard Morris Hunt was the architect. Looking at the detail…the artistry… I have a degree in architecture, but I can't imagine envisioning such design, much less finding people with the talent to implement it. And once you have the house designed, you have to furnish it! All this done in two years? It's astonishing. How could I resist having my own fictional ball in this massive hall? (below)

Dining RoomThe Music Room is decorated in real gold, and the Dining Room has columns of alabaster. Richard Morris Hunt was the architect. Looking at the detail…the artistry… I have a degree in architecture, but I can't imagine envisioning such design, much less finding people with the talent to implement it. And once you have the house designed, you have to furnish it! All this done in two years? It's astonishing. How could I resist having my own fictional ball in this massive hall? (below)

Neily and Grace

Neily and Grace Vanderbilt

When the Breakers was finished in 1895, the Vanderbilts were going through a bit of a personal crisis, as their son Cornelius III (Neily) had fallen in love with Grace Wilson, who had been secretly engaged to his older brother Bill, before Bill died of typhoid. In spite of his parents' objections, Neily and Grace were married in 1896 and were cut out of the will. They were married their entire live. Neily's mother didn't reconcile with him until 1926.

Morning RoomAlfred, the third Vanderbilt son, died in the sinking of the Lusitania. Next son, Reginald, was the father of Gloria Vanderbilt—the grandmother of journalist Anderson Cooper. Daughter Gertrude married Harry Payne Whitney and became a patron of art and formed the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931. She was also a sculptor and designed the Titanic monument in Washington, D.C., honoring the men who gave their lives so women and children could be saved. Their youngest daughter became a countess by marrying Hungarian Count László Széchenyi.

Morning RoomAlfred, the third Vanderbilt son, died in the sinking of the Lusitania. Next son, Reginald, was the father of Gloria Vanderbilt—the grandmother of journalist Anderson Cooper. Daughter Gertrude married Harry Payne Whitney and became a patron of art and formed the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931. She was also a sculptor and designed the Titanic monument in Washington, D.C., honoring the men who gave their lives so women and children could be saved. Their youngest daughter became a countess by marrying Hungarian Count László Széchenyi.

Gladys Vanderbilt

Gladys Vanderbilt by John Singer SargentC-2 didn't have long to enjoy the Breakers. He had his first stroke the year after it was finished, and died in 1899 from a cerebral hemorrhage from a second stroke at the young age of 55.

He left the home to his wife, who left it to Gladys—who always loved the estate. In 1942 she leased it to the Newport Preservation Society for $1, but in 1972, the Society purchased it from Gladys' daughter Countess Sylvia Szapary for $365,000. The family still owns the furnishings. What a bargain! When Sylvia died in 1998, she left the estate to her two children, who continue to spend time there, up on the third floor, away from the tourists. Over 300,000 people visit the Breakers every year. You really should be one of them. Newport Mansions//Nancy

April 7, 2011

A Romantic Stroll

The Cliff Walk… doesn't it sound like the perfect place for a romance, or a Gothic tale? That's one reason I chose it as an integral element in An Unlikely Suitor. Walking along its 3.5 mile length with my husband conjured up images of Newport in its prime, during the last half of the 19th century…

The Cliff Walk… doesn't it sound like the perfect place for a romance, or a Gothic tale? That's one reason I chose it as an integral element in An Unlikely Suitor. Walking along its 3.5 mile length with my husband conjured up images of Newport in its prime, during the last half of the 19th century…

The nice thing about nature is that the basics remain the same. And so the essence of the Cliff Walk remains much as it was so long ago. Considering Newport has been around since 1639, the original paths along the shore of Rhode Island Sound and the Atlantic were probably originally worn down by deer and the Narragansett Indians. When European settlers lived there, they would go down to the rocks to recover goods from ship wrecks.

For the sea could be harsh and the rocks along the shore were (and are) jagged and dangerous. Yet there's something very exciting about walking on a narrow path with civilization on the one side, and the fierceness of nature on the other. Standing on the Walk, looking out to sea, the centuries fall away and you feel a connection with all that came before.

Newport began to be a summer haven of wealthy New Englanders as far back as 1850. As is the way since time began, people liked having a home with a view, and so homes were built along the edge of the ocean. As the century progressed, the first homes were replaced with palatial mansions that had grounds rivaling the lush estates of Europe. Instead of merchants and politicians building there, the extraordinarily wealthy "Robber Barons" of the Gilded Age took over: the Vanderbilts and Astors built summer "cottages" that were as large as twenty homes.

Newport began to be a summer haven of wealthy New Englanders as far back as 1850. As is the way since time began, people liked having a home with a view, and so homes were built along the edge of the ocean. As the century progressed, the first homes were replaced with palatial mansions that had grounds rivaling the lush estates of Europe. Instead of merchants and politicians building there, the extraordinarily wealthy "Robber Barons" of the Gilded Age took over: the Vanderbilts and Astors built summer "cottages" that were as large as twenty homes.

The Forty Steps The Cliff Walk was a place for all classes. Although the wealthy lived along its edges, the servants who worked in those houses were free to use the Walk. At the north end are the 40 Steps. Here's a photo of the wooden steps taken during that olden time. The steps ended on the rocks. It was a gathering place for the working class who would have parties where they'd dance and sing Irish music. Since that time, the steps have been improved, from wood to more sturdy stone.

The Forty Steps The Cliff Walk was a place for all classes. Although the wealthy lived along its edges, the servants who worked in those houses were free to use the Walk. At the north end are the 40 Steps. Here's a photo of the wooden steps taken during that olden time. The steps ended on the rocks. It was a gathering place for the working class who would have parties where they'd dance and sing Irish music. Since that time, the steps have been improved, from wood to more sturdy stone.

Servants gathering

Servants gathering on the Cliff Walk

As the Walk gained in popularity, improvements were made a little at a time. Now, most of the Walk is paved, though there are still areas where you are virtually walking on rocks. But in the 1890's (the era of my book) it was a more dangerous place and every year there were accidents and even deaths. I'll leave it at that…

My husband on the Cliff Walk

My husband on the Cliff Walktelling me "How about this one?" What did the rich home owners think about the lower classes walking within a hundred feet of their back porticos? They were not amused. At various times in history, the homeowners tried to restrict access. At one point they even dropped the Walk 12' below the land-line so walkers couldn't see their houses. They'd plant bushes, put rocks in the way, or even use guard dog.

But many embraced the merging of their property and the Cliff Walk and made improvements, including nice walls to sit upon and bridges. The bottom line is the walk is a public place and all are welcome to embrace its beauty and honor its history. Go to Newport and take a walk. You won't be disappointed.//Nancy

But many embraced the merging of their property and the Cliff Walk and made improvements, including nice walls to sit upon and bridges. The bottom line is the walk is a public place and all are welcome to embrace its beauty and honor its history. Go to Newport and take a walk. You won't be disappointed.//NancyApril 3, 2011

Home on the Plains: Quilts and the Sod House Experience

turned around and pointed at the bed pictured here and said, "Right there."I looked at the quilt on the bed and wondered ... "What kinds of quilts did those women have?"

turned around and pointed at the bed pictured here and said, "Right there."I looked at the quilt on the bed and wondered ... "What kinds of quilts did those women have?" So I went on a search for quilts used in Sod Houses. Fellow author and textile historian Kathy Moore joined the fray and together we combed museum collections and the Solomon Butcher photographic collection for evidence. And we found quilts and women's stories. We share some of them in the new book ... a true work of my heart and the result of years of research, miles spent driving gravel and dirt roads, untold hours in archives ... and at the sewing machine.

co-author Kathy and I also MADE about a dozen quilts for the project, taking inspiration from

the antique quilts we discovered and creating a variety of reproductions and/or "new variations on the theme."

the antique quilts we discovered and creating a variety of reproductions and/or "new variations on the theme."You'll note that the woman pictured on the book cover has spread a couple of her quilts on the fence in front of her sod house just before the photographer took her photo. What does that say about her? Did she make them? Or did the woman you can't see (seated in the wagon the mules are pulling) make them? We'll never know which member of the Comer family created these quilts, but we do know part of their story. As a woman, the most interesting "detail" to me is that Mrs. Comer had Sarah Ellen in 1872,Cora in 1875 (who died in 1876), Paschal in 1877, Minnie May in 1880, Hattie Bell in 1883, Georgie in 1885, Andrew in 1886, James in 1889, Melville in 1891, and Mary Elizabeth in 1903. Makes me tired just to tell you about it ... but that's the kind of "news" that keeps me writing stories.

In the case of this book, all the stories are true. I hope you'll enjoy meeting school-marm Susan Payne, young mother Luna Kellie, grandmother Maria Newton, and the other women featured in this book intended to be a tribute to our pioneer foremothers. The book also includes patterns for how to make some of the featured quilts. There's a sneak peek of sample pages on the home page of www.stephaniewhitson.com (and a way to order an autographed copy.

P.S. I made the blue quilt on the cover (and several others featured in the book) ... but I had a lot of help with the quilting.

__________________________________

I also want you to know about a re-release of The Story Jar by author friends Robin Lee Hatcher and Deborah Bedford.

The Story Jar…

The jar itself is most unusual—not utilized in the ordinary way for canning or storing food, but as a collection point for memories. Some mementos in the jar—hair ribbons, a ring, a medallion--are sorrowful, others tender, some bittersweet. But all those memories eventually bring their owners to a place of hope and redemption in spite of circumstances that seemingly have no solution.

Isn't the idea of a jar of stories appealing? Hope you like it!Robin got the story idea while speaking in Nebraska ... she shares the "story behind the story" ....

In September 1998, I received a story jar as a thank you gift after speaking at a writers' conference in Nebraska. The small mason jar, the lid covered with a pretty handkerchief, was filled with many odds and ends – a Gerber baby

spoon, an empty thread spindle, a colorful pen, several buttons, a tiny American flag, an earring, and more.

The idea behind this gift was a simple one. When a writer can't think of anything to write, she stares at one of the objects in the jar and lets her imagination play. Who did that belong to? How hold was he? What sort of person was he? What does the object represent in his life?

Writers love to play the "what if" game. It's how most stories come into being. Something piques their interest, they start asking questions, and a book is born.

A week after receiving my story jar, I attended a retreat with several writer friends of mine, Deborah Bedford included. On the flight home, I told Deborah about the jar. The next thing you know (after all, what better thing is there for writers to do on a plane than play "what if"?), we began brainstorming what would ultimately become The Story Jar. We decided very quickly that we wanted this to be a book that celebra

tes motherhood, that encourages mothers, that recognizes how much they should be loved and honored.

The Story Jar was first published by Multnomah in 2000, but eventually went out of print. Thus Deborah and I are delighted that Hendrickson wanted to bring it out in a new, revised version because we believe these stories can inspire others, just as it did this reader back in 2001:

"I am an avid book reader and have read thousands of books––maybe more––since the age of 5. I can honestly say that [The Story Jar] has touched me more than any other I have read. I cried, I laughed, and I relearned

things that

I had forgotten long ago as well as realizing things I never knew. Thank you for sharing your stories with your readers. They are truly inspiring. I plan on giving it to all the 'mothers' in my life for Mother's Day."

You don't have to be a writer to want a story jar. It can be a family's way of preserving memories. Consider having a family get-together where everybody brings an item to go into the jar, and as it drops in, they tell what it means to them, what it symbolizes. We can learn something new about our loved ones when we hear their memories in their own words. Or do what my church did a number of years ago to create a memory for a retiring pastor. Inspired by The Story Jar, members of the congregation brought items to the retirement dinner to put into a story jar or they simply wrote their memories on a piece of paper to go into the jar. It

was our way of saying thanks to a man and wife for all of the years they'd given in God's service.

A story jar can be a tool for remembering all the wonderful things God has done in our own lives. As Mrs. Halley said, not all of God's miracles are in the Bible. He is still performing them today in countless ways

today, changing lives, healing hearts

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

.Robin Lee Hatcher is known for her heartwarming and emotionally charged stories of

faith, courage, and love. She makes her home in Idaho where she enjoys spending time with her family, her high-maintenance Papillon, Poppet, and Princess Pinky, the kitten who currently terrorizes the household

.

When Deborah Bedford isn't writing, she spends her time fly-fishing, cheering at American Legion baseball games, shopping with

her daughter, singing praise songs while she walks along the banks of Flat Creek, and

her daughter, singing praise songs while she walks along the banks of Flat Creek, and taking her dachshund Annie for hikes in the Tetons where they live

.

Order your copy here:

http://www.amazon.com/Story-Jar-Robin-Lee-Hatcher/dp/1598566652/ref=sr_1_5?ie=UTF8&qid=1301937371&sr=8-5

Visit Robin and Deborah at: http://www.robinleehatcher.com/& http://www.deborahbedfordbooks.com/

Have a fabulous week! Spring's coming!

March 28, 2011

Marseille, France, 1700s, and white corded quilting

In a recent post, Nancy told us that American dressmakers often looked to France for inspiration, but as the 19th century wore on, they became increasingly independent in their design ideas. I recently attended a lecture that made me aware of just how far-reaching the French fashion industry has been over the centuries.

Godey's Ladies books might have broughtFrench fashion to America in the 19th century, but the French were "all about fashion" long before that!

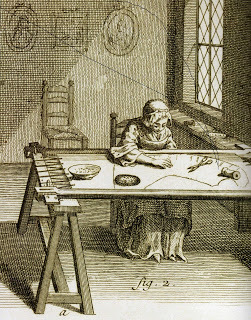

The lecture I attended was sponsored by the International Quilt Study Center and Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, in conjunction with their current exhibition titled Marseille: White Corded Quilting, which features phenomenal works from the collection of Kathryn Berenson and others. See more of the exhibition athttp://www.quiltstudy.org/exhibitions/online_exhibitions/marseilles.htm.

Because of my love of all things French ... and my passionate interest in quilting traditions ... Berenson's books pictured here are two favorite reads.When I look at the engraving above of the woman bent over the quilting frame in an atelier in France, I can't help but wonder what her life was like. She spent hours a day creating phenomenal quilted clothing. What would she think if she could see us today as we stand in open-mouthed wonder at her exquisite handiwork?

Because of my love of all things French ... and my passionate interest in quilting traditions ... Berenson's books pictured here are two favorite reads.When I look at the engraving above of the woman bent over the quilting frame in an atelier in France, I can't help but wonder what her life was like. She spent hours a day creating phenomenal quilted clothing. What would she think if she could see us today as we stand in open-mouthed wonder at her exquisite handiwork?Among the more jaw-dropping things I learned from speaker Frederique Sevet-Collier at the lecture that day was that, by 1680, the women working in

the textile ateliers of Marseille, France, were producing 40-50,000 pieces of whitework a year. Tens of thousands.

the textile ateliers of Marseille, France, were producing 40-50,000 pieces of whitework a year. Tens of thousands.What's corded whitework? Draw a design on a piece of white cloth, then layer that with a backing fabric and stitch along the design. Finally, separate the weave on the back layer to introduce a length of white cording into the channel created by the stitching. How many hours do you suppose it took to create even a small piece? Surely hundreds of hours. Other more intricate pieces in this exhibition would have required thousands of hours.

While the Marseilles whitework industry was nearly eliminated by the Plague, quilted clothing remained in vogue for centuries. I am still amazed by the work that went in to making beautiful petticoats like this one in my personal collection. Petticoat ... as in ... undergarment rarely seen by anyone but the wearer. Amazing ... and somewhat simplistic compared to the pieces on display at the museum. Still, as I run my hand over the feathers quilted into the hem, I imagine "her" ... and I'm inspired to attempt to tell her story.

Of course "she" lives on the Great Plains in the 19th century, not at Louis XIV's court. She's a newcomer to fashion compared to the ladies who wore the creations from Marseilles. Still....I wonder....what if one of those women's creations traveled to the New World in a trunk aboard a ship .... what if ....

Of course "she" lives on the Great Plains in the 19th century, not at Louis XIV's court. She's a newcomer to fashion compared to the ladies who wore the creations from Marseilles. Still....I wonder....what if one of those women's creations traveled to the New World in a trunk aboard a ship .... what if ....

March 24, 2011

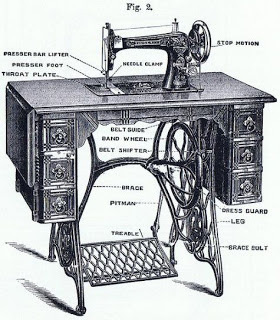

Treadle sewing

I wax nostalgic when the topic of treadle sewing machines comes up, because .... I learned to sew on one. At Clark Junior High School in East St. Louis, Illinois, we had an entire row of them in the Home Ec classroom, and that's what we used to create our fully lined black wool sheath dresses, and our two-piece wool pants suits. Pedal-pedal-pedal-pedal! In 1963-4. (And then of course we climbed aboard the covered wagon to go home. Uphill. Both ways. In the snow.)

For years my Grandmother's treadle sewing machine was part of our home decor. (Grandma Rose was Grandpa's sixth wife, but that's a topic for another blog. Or not.) I remember the drawers still housing all the attachments, and how I wish I had Grandma Rose's machine back...I'd probably use it!

As Nancy reminded us a few posts ago, the sewing machine changed women's lives forever. Reading her blog reminded me of some anecdotes I've come across in my studies of 19th Century Great Plains women.

In 1867, a Nebraska pioneer woman wrote, Didn't this sewing machine help me long fast. I never mean to sew by hand any more if I can help it.

In 1878, Nebraskan Mattie Oblinger wrote about her Mother's sewing machine back home, "I wish I was near enough for awhile to do some sewin' on. I have so much to do I do not know where to commence." Later that same year she wrote, "I had to make some new clothes for the girls to wear to the fair, and I was very much hurried as I done it all by hand. Mother, I often wish I was close to your machine for three girls makes lots of sewin'."

Iowa farm wife Emily Gillespie was so thrilled to get a sewing machine, she wrote about it in her diary. I finished Henry's clothes, took me just 49 hours to make coat, pants, and vest. "Just 49 hours" .... Oh my.

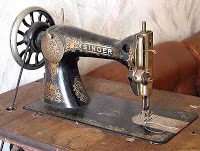

Nebraska sod house homemaker Luna Kellie wrote, J.T. had bought me a new Singer Machine and I made good use of it making all the clothes we all wore. I had done this before by hand only occasionally taking some long seams down to sew on Mrs. Strohls machine. Machines were not so high then I think we paid 30 or 35 dollars for it.

At least J.T. wasn't like one husband I read about who said that he thought that twenty or twenty-five dollars was a lot of money to pay for a machine that did "little more than lighten a woman's work load." Where do you suppose he's buried :-).

Ranch wife Grace Snyder had been married four years before she saved enough to buy a sewing machine by raising an orphaned calf. Imagine her joy when her husband returned from a supply run to town with that machine in the wagon ... and imagine her disappointment when they discovered he'd only brought the cabinet! The machine head, shipped in a separate crate, was still back at the train depot with the rest of the load. It would be a few days before the working part arrived!

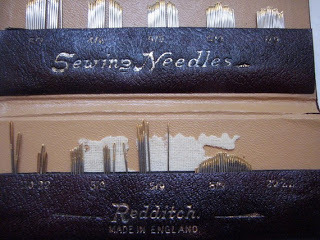

For all the advances in women's sewing tools, I still think there's something to be said for the soothing monotony of hand stitching. I have a wonderful sewing machine and a Featherweight, but I still love to thread a needle (the thread spools perch on this antique thingy (what's it called?) and stitch by hand. And I honestly believe that our pioneer foremothers enjoyed it, too--in spite of all they had to accomplish. There is great satisfaction at looking at a bit of needlework and saying, 'I made that." Dinners get eaten, cookies disappear, laundry just has to be done again ... but stitching? Stitching often outlasts the hands that do it.

--Steph

Sew 'n Sew

There are some inventions you marvel over, and wonder why someone didn't invent it earlier: Velcro, Scotch tape, rollers on suitcases, Chapstick. . . But there are other inventions that were invented early on, as if humanity made them a priority. One such necessity that spans the ages and all geography are sewing needles. By varying accounts, they've been around 20,000 years. I consider that pretty much forever.

There are some inventions you marvel over, and wonder why someone didn't invent it earlier: Velcro, Scotch tape, rollers on suitcases, Chapstick. . . But there are other inventions that were invented early on, as if humanity made them a priority. One such necessity that spans the ages and all geography are sewing needles. By varying accounts, they've been around 20,000 years. I consider that pretty much forever. People have needed to sew since Adam and Eve first wanted to get dressed. The first needles were made from animal bone and didn't have an eye, but a slit in the top to hold the thread (which was made from animal sinew.) Metal needles followed, but were often made by the town blacksmith, which means they were often crude in design. England was one of the first places to mass produce them, and the town of Redditch became known for its manufacturing. In 1866 Redditch produced 100 million needles! There's a museum you can visit there: Forge Mill

People have needed to sew since Adam and Eve first wanted to get dressed. The first needles were made from animal bone and didn't have an eye, but a slit in the top to hold the thread (which was made from animal sinew.) Metal needles followed, but were often made by the town blacksmith, which means they were often crude in design. England was one of the first places to mass produce them, and the town of Redditch became known for its manufacturing. In 1866 Redditch produced 100 million needles! There's a museum you can visit there: Forge Mill In 1755 the first sewing machine was invented by the German inventor, Karl Weisenthal, who created the first sewing machine needle, but never finished the invention of the machine. The first machine that was usable was invented in 1790, by British Inventor, Thomas Saint. It only used one thread to form a chain stitch, and was mostly used on shoes. It didn't have a needle, but used an awl to get through the heavy leather fabric. And it never was produced beyond the patent model.

The next inventor was French. In 1830 Barthelemy Thimonnier patented the first sewing machine that actually was sold. It also produced a chain stitch and was used to sew uniforms for the French army. But tailors voiciferously—and violently—objected to this machine, believing it would hurt their business. They mobbed Thimmonnier's factory, and destroyed it. He fled to England and died bankrupt.

The next inventor was French. In 1830 Barthelemy Thimonnier patented the first sewing machine that actually was sold. It also produced a chain stitch and was used to sew uniforms for the French army. But tailors voiciferously—and violently—objected to this machine, believing it would hurt their business. They mobbed Thimmonnier's factory, and destroyed it. He fled to England and died bankrupt.The man who figured out the two-thread system we use today was American Walter Hunt in 1834—he also invented the safety pin. But he gave up the invention when he became convinced that his sewing machine would cause too many seamstresses to be out of work.

Elias Howe Jr. lived on the edge of poverty and watched his wife as she worked as a seamstress. He got the idea to copy the movement of the human arm and created a machine that made a lock-stitch. He had a public contest against women sewing by hand and finished five seams before any of them had finished even one. But no one bought a machine. He went to England to try to sell some, but when he returned, he found more than one sewing machine on the American market, many using his patented mechanisms. He sued and agreed on taking royalties. He made nearly $2 million by getting a cut in the sale of other people's machines

Elias Howe Jr. lived on the edge of poverty and watched his wife as she worked as a seamstress. He got the idea to copy the movement of the human arm and created a machine that made a lock-stitch. He had a public contest against women sewing by hand and finished five seams before any of them had finished even one. But no one bought a machine. He went to England to try to sell some, but when he returned, he found more than one sewing machine on the American market, many using his patented mechanisms. He sued and agreed on taking royalties. He made nearly $2 million by getting a cut in the sale of other people's machines The inventor who finally got it right has a familiar name: Singer.

In 1851, Isaac Singer patented his version, the first rigid-arm sewing machine. Previous to this, the arm vibrated with the needle. Singer's machine included a presser foot to hold the cloth steady. And sales really popped when he figured out how to let the sewer power the machine with their feet, via a treadle vs. a hand crank.

In 1851, Isaac Singer patented his version, the first rigid-arm sewing machine. Previous to this, the arm vibrated with the needle. Singer's machine included a presser foot to hold the cloth steady. And sales really popped when he figured out how to let the sewer power the machine with their feet, via a treadle vs. a hand crank.

Singer brought the sewing machine to the people. He advertised, and provided service-after-the-sale. He sold the machines for $75-$125 in fancy showrooms, and let people pay in installments. This was essential for sales, as the normal annual income was $500 and as such, people would have to pool their money to buy a single machine for an entire small town.

But then a young farmer, James Gibbs, saw a picture of a Singer machine and made his own. He teamed up with James Willcox to sell a lighter, cheaper model than the expensive Singer (he sold his for $50.) Willcox & Gibbs sold machines until the 1970's.

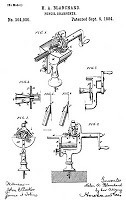

Helen Blanchard patent drawings Women made improvements to the machines too, and many patents were given to women. Helen Blanchard of Maine invented the zigzag sewing machine and in 1881 started the Blanchard Over-seam Company. Very mechanically inclined (and self-taught) she was awarded 28 patents.

Helen Blanchard patent drawings Women made improvements to the machines too, and many patents were given to women. Helen Blanchard of Maine invented the zigzag sewing machine and in 1881 started the Blanchard Over-seam Company. Very mechanically inclined (and self-taught) she was awarded 28 patents.  In my new novel An Unlikely Suitor, my two immigrant seamstresses go from working in a sweatshop making ready-to-wear, to working for a private dressmaker, sewing custom-made designs for a rich clientele. Knowing how to use a sewing machine was invaluable.

In my new novel An Unlikely Suitor, my two immigrant seamstresses go from working in a sweatshop making ready-to-wear, to working for a private dressmaker, sewing custom-made designs for a rich clientele. Knowing how to use a sewing machine was invaluable.

As is the normal cycle of any "new" machine on the market, the price eventually went down so they were more affordable. The fact many women could have their own machine changed their lives drastically. Before machines (according to Godey's Lady's Book) it took fourteen hours to make a man's shirt and ten to make a simple dress. So women spent a lot of their day mending and sewing for their families. But with a sewing machine . . . suddenly a woman could sew a shirt and dress in about an hour.

What to do with all that free time? Women were able to think beyond the home . . . and the world has never been the same.//Nancy

March 18, 2011

I'll Take Thirty Dresses

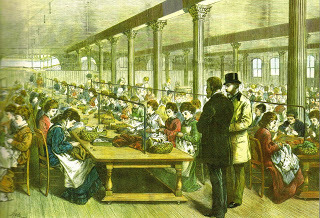

Made-to-order workroom in Stewart'sMy novel An Unlikely Suitor begins in a dressmaking shop in New York City in 1895. Off-the-rack clothes were no longer a novelty and could be purchased at a myriad of department stores (Macy's, Bloomingdale's, Stewart's, Bergdorf-Goodman…) Many stores offered both custom made clothing as well as ready-to-wear, which was often sewn to fit on the premises. Women could also order clothing from catalogs. But with all these options, most high-society ladies still had their wardrobes custom designed and sewn, often in small dress-shops. In my book it's Madame Moreau's Fashion Emporium. The "Madame Moreau" in the store's name is in reaction to a fascination with all things French. Actually, the woman who runs the store is named Mrs. Flynn, who had the uncanny ability to adopt a French accent when dealing with her clientele. These dressmakers often imported Paris fashion—to copy, although in the 1890's they were taking more and more pride in their own developing American fashion.

Made-to-order workroom in Stewart'sMy novel An Unlikely Suitor begins in a dressmaking shop in New York City in 1895. Off-the-rack clothes were no longer a novelty and could be purchased at a myriad of department stores (Macy's, Bloomingdale's, Stewart's, Bergdorf-Goodman…) Many stores offered both custom made clothing as well as ready-to-wear, which was often sewn to fit on the premises. Women could also order clothing from catalogs. But with all these options, most high-society ladies still had their wardrobes custom designed and sewn, often in small dress-shops. In my book it's Madame Moreau's Fashion Emporium. The "Madame Moreau" in the store's name is in reaction to a fascination with all things French. Actually, the woman who runs the store is named Mrs. Flynn, who had the uncanny ability to adopt a French accent when dealing with her clientele. These dressmakers often imported Paris fashion—to copy, although in the 1890's they were taking more and more pride in their own developing American fashion.

Bloomingdale's 1888 catalog

Bloomingdale's 1888 catalog

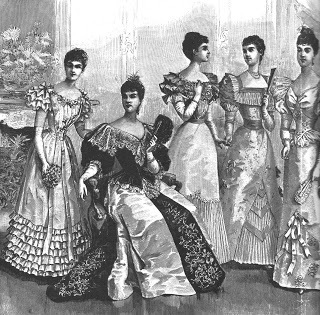

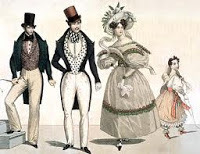

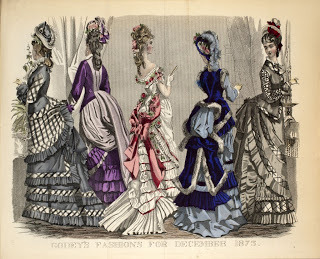

1830's

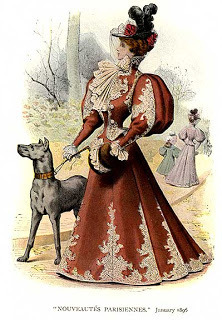

1830'sAlthough the complexity of the bustle-era was gone (illustration at left is 1888), dresses in the mid-1890's were far from simple. The focus moved from the back of the dress to the sleeves—or actually to the waist. For by making the sleeves ridiculously huge, a woman's waist appeared tiny in comparison. And in the everything-old-is-new-again phenomenon, it should be noted that these sleeves were also popular in the 1830's. But during that time, skirts were also wide, making women look as if they were swallowed up by their clothes! Too much.

Fashion is all about silhouettes. To create the hour-glass silhouette of the 1890's, a wide top and small middle was needed.

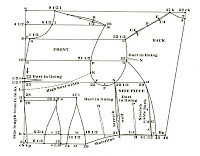

Fashion is all about silhouettes. To create the hour-glass silhouette of the 1890's, a wide top and small middle was needed.  bodice patternThe over-sized puffy sleeves were called gigots, or leg-o-mutton sleeves. They were often made from four separate pieces of fabric (most sleeves nowadays are cut from one piece), and they could be stuffed so they kept their shape. Skirts were often four or six gores, or had insets of gathers at the thigh-level (as a seamstress myself, I know these insets would be difficult to do.) Even though the patterns to ,make these clothes were still far from simple, it was a big step for women's fashion to lose the bustle.

bodice patternThe over-sized puffy sleeves were called gigots, or leg-o-mutton sleeves. They were often made from four separate pieces of fabric (most sleeves nowadays are cut from one piece), and they could be stuffed so they kept their shape. Skirts were often four or six gores, or had insets of gathers at the thigh-level (as a seamstress myself, I know these insets would be difficult to do.) Even though the patterns to ,make these clothes were still far from simple, it was a big step for women's fashion to lose the bustle.  Note the inset flared skirts on the rightTo herald the new style came the "shirtwaist". It became the uniform of working women everywhere: a relatively plain skirt with a leg-o-mutton blouse that had a standing band collar and buttons up the back. A simple petticoat was all that was needed—except for the dratted corset, of course. It would still be twenty-five years before women rid themselves of that awful contraption. Wearing this relatively simple ensemble women were able to go to college, work, and enjoy sports such as golf or tennis.

Note the inset flared skirts on the rightTo herald the new style came the "shirtwaist". It became the uniform of working women everywhere: a relatively plain skirt with a leg-o-mutton blouse that had a standing band collar and buttons up the back. A simple petticoat was all that was needed—except for the dratted corset, of course. It would still be twenty-five years before women rid themselves of that awful contraption. Wearing this relatively simple ensemble women were able to go to college, work, and enjoy sports such as golf or tennis.

But forget shirtwaists for the rich patronesses of the dress shops. They wanted custom designs that made them stand out from the masses of women wearing the simpler styles.

But forget shirtwaists for the rich patronesses of the dress shops. They wanted custom designs that made them stand out from the masses of women wearing the simpler styles.The dressmaking shops were often staffed by immigrants, first or second generation Americans. They created the intricate patterns for the dresses, cut the fabric (which was purchased in varying non-standardized widths. Now, we basically have 45", 54", and 60" widths to choose from), and sewed the garments on machines and by hand (I'll be blogging about the evolution of the sewing machine next week.) The elite of society kept these shops busy with their need to showcase their family's successes and wealth through their fashion. To walk the streets of New York City in elegant finery, to take a promenade through Central Park, to go to the opera or Delmonico's, to attend a ball or dinner at the Astor's or Vanderbilt's, demanded fashion that wowed the viewer. Has much changed today? Don't we also long to be thought of as fashionable?

Now here's an age old question: did women dress for men or women? Do we dress for men or women now? The fashion of the late nineteenth century tried to emphasize a woman's figure (even if it was completely covered). But I still think most women dress for the appreciation of other women. For do men really know if something is fashionable or not? Women notice. Women know.

Another reason the dressmaking shops kept busy was the summer season. Many of the members of the Four Hundred of New York society went to Newport, Rhode Island for six to eight weeks at the end of every summer. There, amid the cool ocean breezes, they created another version of society, with as many rules and standards as they had in the city. Each woman needed nearly thirty new outfits for this season.

That's the starting point in An Unlikely Suitor. A mother and daughter enter Madame Moreau's in need of an entirely new wardrobe…only the daughter suffers from an infirmity that causes her dresses to hang oddly. Enter the heroine, Lucy Scarpelli to find a sewing solution. And so a friendship between immigrant seamstress and wealthy heiress is born . . . and continues as Lucy gets a chance to join Rowena in Newport. It's a classic premise of friendship between a poor girl and a rich girl, set amid the lavish opulence of Newport, with the breeze blowing off the Cliff Walk, and handsome young men with time on their hands . . . Trust me, the story is well . . . sewn.//Nancy

March 14, 2011

1896 Spokane, WA & New York City with Jane Kirkpatrick, author of The Daughter's Walk

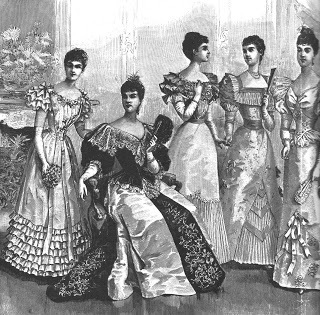

In 1896 Helga Estby and her daughter, Clara, made an historic walk from Spokane, WA to New York City hoping to earn $10,000 from the fashion industry that would be enough to save their family farm.

In 1896 Helga Estby and her daughter, Clara, made an historic walk from Spokane, WA to New York City hoping to earn $10,000 from the fashion industry that would be enough to save their family farm. In 2003, when novelist Jane Kirkpatrick finished reading a book about that walk, what struck her was the unfinished story: that upon their return from the walk, Clara, the daughter, changed her last name and was separated from the family for twenty years. Jane wanted to know what happened, why did she change her name? What did she do during those years? What brought the reconciliation after that extended exile? "I also liked the idea that one of the few things Clara carried with her as they followed the railroad track across the continent was a curling iron. What did that tell us about her character, or did it tell anything at all?"

The result of Jane's quest to find answers and to know "the story behind that story" resulted in her new release, the Daughter's Walk.

The result of Jane's quest to find answers and to know "the story behind that story" resulted in her new release, the Daughter's Walk.

I'm thankful to Jane for agreeing to visit today and share some of the "footnotes from history" that led her to tell this unique story.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about "the real story" while researching this book? I found Clara living about 50 miles from Spokane during most of the separation and that she later became quite a successful business woman owning many properties in Spokane and eventually living not all that far from her biological family. Descendants whom I interviewed were stunned to know their great aunt had actually lived so nearby. They were also surprised to discover that the house Clara and her sister -- after the reconciliation -- lived in was owned not by the sister but by Clara. I also discovered that she had two close women friends who had been furriers in New York City about the time of the historic walk. That set me on the journey to research fur fashions in the early 1900s and took me to a contemporary fur auction, one of the largest in the Northwest and one that Clara and her business partners likely attended more than once years before. The Fur Commission staff were wonderful in helping me speculate about Clara's life during that time and told me that she would have had to have a male agent as women wouldn't have been allowed to bid at the fur auction. That helped explain a family story about Clara sometimes traveling to Europe "with a man" on business. Several years ago I wrote a series of books called the Tender Ties Series about a woman involved in the fur industry in the early 1800s. Now here I was researching that same industry in early 1900. It was fascinating to see what changes had occurred and how Clara might have been involved. Is there a historical

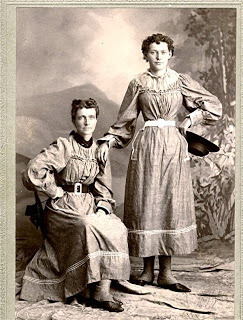

photograph that inspired you you'd like to share? On the left! To earn their way across the country, they had photographs taken which they sold for a nickel. Part of the reason we know about this journey at all is because a few of those pictures were saved by a relative and others were located in archival copies of newspapers. The women were to wear the new reform dress once they reached St. Lake City and they also modeled the dresses while in Chicago. Most photographs showed off their high button shoes, scandalous for the time period when modesty meant ankles were covered and corsets worn daily. What one non-fiction book helped you research the most Linda Lawrence Hunt's book Bold Spirit: Helga Estby's Forgotten Walk Across Victorian America (Random House, 2003) Her book tells of the walk, the social challenges of the period and explores the great silencing of the story by family after the women returned. It was there I read about Clara's name change and separation. Little was known though about what Clara did after the return and that's what I wanted to explore through fiction. I also wanted to imagine what Clara might have been thinking as a teenager walking across the country for eight months with her mother.What spiritual encouragement did you draw from what you've learned? I had to explore the great emptiness of exile, of being sent out or away and how much we may play in that journey by our choices. I actually ached for Clara at times knowing her family was physically so close and yet so emotionally distant. Her efforts to deal with that made me sad and I longed for her to find a way to step over whatever had caused the rift and to mend the break. When we feel separated from God I think the pain is profound yet not unlike the heartache when a family rift defines our every day. It's said that forgiveness is required of us as Christians, as God forgave us; but reconciliation is not. That becomes a choice and it made me conscious of rifts within my own family that I wanted to heal. The story also made me want to seek forgiveness for my own choices that left me separated from God and to take action to allow Him to seek me out.

photograph that inspired you you'd like to share? On the left! To earn their way across the country, they had photographs taken which they sold for a nickel. Part of the reason we know about this journey at all is because a few of those pictures were saved by a relative and others were located in archival copies of newspapers. The women were to wear the new reform dress once they reached St. Lake City and they also modeled the dresses while in Chicago. Most photographs showed off their high button shoes, scandalous for the time period when modesty meant ankles were covered and corsets worn daily. What one non-fiction book helped you research the most Linda Lawrence Hunt's book Bold Spirit: Helga Estby's Forgotten Walk Across Victorian America (Random House, 2003) Her book tells of the walk, the social challenges of the period and explores the great silencing of the story by family after the women returned. It was there I read about Clara's name change and separation. Little was known though about what Clara did after the return and that's what I wanted to explore through fiction. I also wanted to imagine what Clara might have been thinking as a teenager walking across the country for eight months with her mother.What spiritual encouragement did you draw from what you've learned? I had to explore the great emptiness of exile, of being sent out or away and how much we may play in that journey by our choices. I actually ached for Clara at times knowing her family was physically so close and yet so emotionally distant. Her efforts to deal with that made me sad and I longed for her to find a way to step over whatever had caused the rift and to mend the break. When we feel separated from God I think the pain is profound yet not unlike the heartache when a family rift defines our every day. It's said that forgiveness is required of us as Christians, as God forgave us; but reconciliation is not. That becomes a choice and it made me conscious of rifts within my own family that I wanted to heal. The story also made me want to seek forgiveness for my own choices that left me separated from God and to take action to allow Him to seek me out.Did you meet a special woman from the past you'd like to tell about? Definitely Clara Estby Dore, the daughter on this journey. Her very wish to do things differently than her mother had actually took her onto paths very similar to her mother's making decisions for family. Cla

ra's journey reminded me that the word family comes from the Latin Famalus meaning servant. I believe that Clara discovered the true meaning of family and deepened my own understanding of family. I hope her journey brings nurture to readers as it did to me.Thanks so much to Jane Kirkpatrick for sharing her footnote from history with us today.To learn more about Jane's other wonderful books, visit her at

ra's journey reminded me that the word family comes from the Latin Famalus meaning servant. I believe that Clara discovered the true meaning of family and deepened my own understanding of family. I hope her journey brings nurture to readers as it did to me.Thanks so much to Jane Kirkpatrick for sharing her footnote from history with us today.To learn more about Jane's other wonderful books, visit her atwww.jkbooks.com

www.wordsofencouragement.blogspot.com

March 11, 2011

Fashion: Action and Reaction

Thinking about fashion in the last two hundred years I started seeing an action/reaction phenomenon going on...

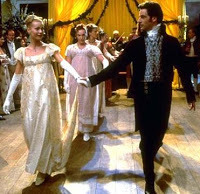

After the French Revolution, women got rid of their ridiculous high wigs and huge side-hoops and wore simple flowing dresses that allowed women freedom. Revolution? Freedom? It goes together. Now when they danced, they could actually get close to their partners, sliding past, shoulder to shoulder. And bonus, they didn't have to worry about their wigs and head-dresses toppling over.

After the French Revolution, women got rid of their ridiculous high wigs and huge side-hoops and wore simple flowing dresses that allowed women freedom. Revolution? Freedom? It goes together. Now when they danced, they could actually get close to their partners, sliding past, shoulder to shoulder. And bonus, they didn't have to worry about their wigs and head-dresses toppling over. As the memories of the Revolution faded, in the 1820's and 30's (see below left) fashion became more constrained again with big sleeves, big skirts, and corseted waists. It's as if the only action possible was over-reaction.

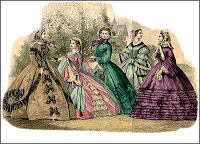

By the 1860's women were encased in a bell. They were unable to go through doors easily, sit in a chair, and were encouraged by the style to be little more than pretty ornaments.

After the war, and during the industrial explosion of the last half of the 19th century, women seemed to gain freedom again with dresses that were flat in front and on the sides. Yet, the grips of fashion wouldn't let them go, and they were burdened with large, elaborate bustles, holding them back, prohibiting them from gaining full freedom. Heavy trains impeded their forward progress.

After the war, and during the industrial explosion of the last half of the 19th century, women seemed to gain freedom again with dresses that were flat in front and on the sides. Yet, the grips of fashion wouldn't let them go, and they were burdened with large, elaborate bustles, holding them back, prohibiting them from gaining full freedom. Heavy trains impeded their forward progress. In the 1890's women escaped the bustles and all forms of hoops (for good!) Once free to move, they . . . moved. Women rode bicycles, played golf and tennis, and went to work in offices using a new invention called a typewriter. The idea of women gaining the right to vote stirred them into believing they actually could wield some power. Their sleeves grew enormous as if mimicking the idea of a strong woman, flexing her muscles.

In the 1890's women escaped the bustles and all forms of hoops (for good!) Once free to move, they . . . moved. Women rode bicycles, played golf and tennis, and went to work in offices using a new invention called a typewriter. The idea of women gaining the right to vote stirred them into believing they actually could wield some power. Their sleeves grew enormous as if mimicking the idea of a strong woman, flexing her muscles.

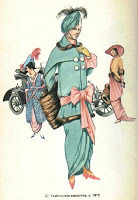

For a few decades women's fashions seemed almost sane—until the teens of the 20th century, when the hobble skirt became the rage. Tight near the ankle, there was only one way to walk in the dress. Slowly, with small steps. Hmm... Was society spooked by the inroads women were making, so it created fashion to hold women back by "hobbling them"?

But women wouldn't be hobbled and kicked free of such ridiculous fashion. The flapper era of the 1920's was a full revolution with corsets banished, hemlines raised from ankle to knee, fabrics softened to flowing sheers, and long hair cut into easy-care bobs. What did women do to celebrate their freedom? They went wild, dancing the Charleston, smoking cigarettes, and drinking cocktails!

Here's a link to original footage from the Roaring Twenties: Charleston Video

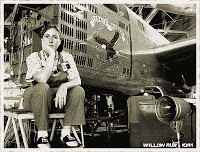

As women moved into the workplace, the flimsy flapper dresses gave way to practical clothes that were more tailored and menswear inspired. For the first time in history, women discovered the comfort of wearing pants (what took them so long? Really.) As our men went to war, women filled in the gaps, working in factories and on the farm.

As women moved into the workplace, the flimsy flapper dresses gave way to practical clothes that were more tailored and menswear inspired. For the first time in history, women discovered the comfort of wearing pants (what took them so long? Really.) As our men went to war, women filled in the gaps, working in factories and on the farm. But after World War II and the Korean War, with our boys back home again, it was as if fashion insisted that women look like women again. Corsets returned—in the form of heavily constructed bras and girdles. Hoops were still out, but in their place came layers of petticoats, once again giving women an ornamental look. And as an alternative, there were tight-tight skirts, which were nothing more than modern hobble skirts.

But after World War II and the Korean War, with our boys back home again, it was as if fashion insisted that women look like women again. Corsets returned—in the form of heavily constructed bras and girdles. Hoops were still out, but in their place came layers of petticoats, once again giving women an ornamental look. And as an alternative, there were tight-tight skirts, which were nothing more than modern hobble skirts.

The style didn't last long, as the late sixties created fashion spurred by social reform. Those were the anti-years. Anti-war, anti-establishment, anti-any constraint at all. Bras were burned, coiffed hair was set free, and the freedom to choose virtually any style teased women with almost too much freedom.

For in the 1980's, when women were making huge strides in the business world, the hippie dress code didn't work in the corporate workplace. And so… fashion once again copied menswear with man-sized shoulder pads and silly bows instead of neckties. Having lived through this style, I cringe. We looked ridiculous in our "power suits", like men-pretenders.

For in the 1980's, when women were making huge strides in the business world, the hippie dress code didn't work in the corporate workplace. And so… fashion once again copied menswear with man-sized shoulder pads and silly bows instead of neckties. Having lived through this style, I cringe. We looked ridiculous in our "power suits", like men-pretenders. Women eventually realized they didn't need to try quite so hard, and fashion evolved into what it is today. Which is? I'm not sure. When I try to think of fashion trends right now it's hard to pinpoint. Hemlines and the width and length of pant legs vary. Shoes span the range from flip-flops to stilettos. Popular colors come and go. Have we finally reached the point where we can wear what we like and what looks good on us, and not have others make the choices for us?

Women eventually realized they didn't need to try quite so hard, and fashion evolved into what it is today. Which is? I'm not sure. When I try to think of fashion trends right now it's hard to pinpoint. Hemlines and the width and length of pant legs vary. Shoes span the range from flip-flops to stilettos. Popular colors come and go. Have we finally reached the point where we can wear what we like and what looks good on us, and not have others make the choices for us?If so, it's about time. Actually, it is about time. For over two hundred years women have suffered their social gains with stops and starts, advances and regressions, and their fashion has followed suit.

Pun intended.// Nancy

March 6, 2011

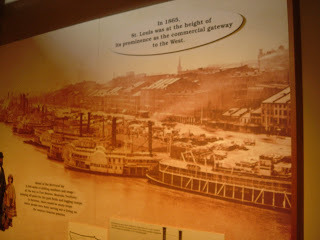

Steamboats on the Missouri

Ah ... steamboats ... how romantic. One of the things I learned researching A Most Unsuitable Match (which is in its final stages of editing--WHEW) was that, in actuality, steamboats on the Missouri were noisy, exasperating, and dangerous. The Missouri presented challenges that Samuel Clemens didn't face piloting the Mississippi.

Ah ... steamboats ... how romantic. One of the things I learned researching A Most Unsuitable Match (which is in its final stages of editing--WHEW) was that, in actuality, steamboats on the Missouri were noisy, exasperating, and dangerous. The Missouri presented challenges that Samuel Clemens didn't face piloting the Mississippi. "We felt the shock and at once the boat started sinking ... (it) keeled over on one side ... there was a wild scene on board ... the chairs and stools were tumbled about and many of the children nearly fell into the water."

"We felt the shock and at once the boat started sinking ... (it) keeled over on one side ... there was a wild scene on board ... the chairs and stools were tumbled about and many of the children nearly fell into the water." So wrote one of the passengers on board the Steamboat Arabia when it hit a snag hiding below the surface of the Missouri River and met its demise. The year was 1856, and the Arabia was only one of some four hundred steamboats to meet their demise while navigating the river called "Old Misery" by those who knew it best.

The lovely hanging lamp above is one example of some of the goods making their way north aboard the steamers that carried virtually millions of tons of freight from St. Louis to Montana in the latter part of the 19th century when gold fever called tens of thousands of hopeful miners to Alder Gulch.

It was seeing the cargo (on a field trip for a history class) a couple of years ago set me on course to write the story of a young girl venturing north from St. Charles Missouri, in search of her only living relative in 1869. I never would have imagined crystal bowls and bolts of silk cloth, ornate dinnerware and silver thimbles, but there they were on display at the museums showcasing the cargo of the Bertrand (in Nebraska) and the Arabia (in Kansas City). What was that like? I wondered, as I read of survivors being hauled ashore and watching as the ship sank in the murky depths.

Those who knew it best called the Missouri an "unpoetic and repulsive stream of flowing mud studded with dead tree trunks and broken by bars." Pilots were constantly challenged by its shifting course and the confines of steep bluffs. Just when a pilot thought he knew the river, she deposited a sand bar and cut away a new bit of bank, leaving new and treacherous barriers just below the surface of the water. The Missouri went through open country that was subject to tornadoes, violent thunderstorms, and fierce gales that could literally blow the shallow-drafted steamers over. Prairie fires could blister the paint when the current forced a steamboat close to the bank and passengers were often tormented by clouds of mosquitoes.

While the record passage from St. Louis to Fort Benton, Montana was "only" twenty-three days, most trips took far longer thanks to exasperating delays from sandbars, broken tillers, failing boilers, and various other challenges including the ever-present threat of boiler explosions, fires, and snags.

And so ... I send eighteen-year-old Fannie Rousseau north aboard a fictional steamboat ... and of course things will not go well.

If you have a chance to visit either historical sites at DeSoto Bend in Nebraska or at the Arabia Museum in Kansas City, you won't be bored. And you'll be thankful for the interstate!