Rosina Lippi's Blog, page 5

June 18, 2017

Pickup Truck

As it’s father’s day I thought I should post this short story, which was published in slightly different form in Redbook (not Good Housekeeping, as I misstated elsewhere) in 1992. It is based on my relationship with my father in the last months of his life, but it is fiction. First hint: my name is not Claudia Busacca.

Pickup Truck

Lately, Claudia Busacca has been noticing that many of the old men she sees, on the street, in the grocery store, everywhere and anywhere she goes, resemble her father. In general, she thinks, there are just a lot of old Italian men around. They are easy to pick out: some are barrel shaped, with heavy heads of shaggy white hair; others have thinned away to a lumpy, hollow frame, so that a belt has to be hitched up high and tight.

In the Greek diner out on Route One late on a Sunday morning, Claudia points out an old man of the first type to her husband. The man sits hunched over a newspaper, following the line of print with one thick finger. His glasses are smudged almost to the point of opacity.

“Who does he remind you of?” Claudia asks Jeff, pointing with her chin.

“An older Spencer Tracy?”

She shakes her head.

“Frank Sinatra, in a good toupe.”

“That’s getting closer.”

“Ah, I get it. Another contestant for the Frank Busacca look-alike contest.”

Claudia smiles. “I just thought he looked very Italian.”

“All old men look Italian to you,” Jeff replies.

***

Back at home, the phone is ringing when they come in the door. It is Joe, Claudia’s older brother, and this is his news: Dad hates all these pills because they make him faint, he isn’t watching his salt, he’s lost another ten pounds, and he won’t let Joe move in with him to keep an eye out.

She hangs up and immediately the phone rings under her hand. She concentrates on the vibration going up her arm. Then she picks it up.

“Hi Daddy,” she says.

“That brother of yours,” he greets her.

***

This is the way it goes: a call from Joe, a call from Dad, then usually Joe again. After Claudia has had a chance to sort out her thoughts, she starts calling them back.

“It might be cheaper to close down the shop and move it to Chicago,” Jeff jokes sometimes when he catches a glance of the telephone bill in the confusion on Claudia’s desk. He has yet to notice that she sees no humor in this.

“What’s this about your salt?” Claudia asks her father now.

“What do you mean? I don’t even have a salt shaker in the house anymore.” He is indignant, huffy. Guilty.

“Joe said something about a bacon and sauerkraut sandwich for breakfast.”

There is a rustling of paper on the other end, things are dropped.

“Daddy, if you don’t watch your salt, you’re always going to be short of breath.”

“I’m short of breath even when I do,” he says.

This tone frightens her more than anything else; she has no way to respond to him that won’t sound like her fear.

“Sometimes I think you want me to live forever, but you don’t want me to have any fun doing it,” he says, finally.

“Don’t you want to live forever?” Claudia asks.

“Of course I do,” he says.

***

Ten years ago, when Joe went into the navy and Claudia left for graduate school, the phone calls were different. Dad was the one with the questions that made her skin jump; he kept calling her back. Then he retired and bought a little pick-up truck and went out on the road for long weeks at a time.

Even then the questions wouldn’t stop: Claudia would get postcards of flimsy cardboard, fuzzy horizons against alarmingly blue skies, sometimes nothing but Daddy scrawled in pencil on the back, but usually with something to do or think about spelled out in clear terms: Call Joe, make nice, you only got one brother; or Transfer $500 from savings to checking; or, How many years will it take you to pay off your student loans?

When Claudia first met Jeff, she had amused him with these postcards and with stories about her father, some her own, some family legend. They featured his temper, his sense of humor, or his adventures. Now, Jeff digs out his favorites when Claudia is especially worried about her father: anecdotes which he has altered ever so slightly, pieces of her life which he has digested into something new, his own. He feeds them to her in small doses, like medicine.

“Do you remember what your father said when you got your master’s?” Jeff asks that night in bed. She is curled on one side away from him.

“He was afraid I wouldn’t get a job. Or I wouldn’t make any money if I did,” she says, yawning.

“He said that he and your mom must have had one heck of a smart iceman.”

Claudia turns over to face her husband. “He said milkman, not iceman.”

“Un-huh. I remember it clearly, I’m sure it was iceman.”

Milkman, Claudia thinks to herself. Milkman, Milkman, Milkman. She tries to swallow this, not wanting to have this discussion, not now.

But then she can’t let it go after all: the fact that Jeff has taken possession of this simple story so completely, that there is no more room for her in the telling of it, that fact irks. It itches. It irritates.

So she tells him something she has never told him before: the end of the story. “Daddy always said that, about — my parentage — whenever I got a good report card.”

Jeff pushes himself up on one elbow to look at her. She has surprised him.

“Did your Mom think it was funny?”

“She laughed every time, she thought it was a great joke.”

“You didn’t?” Jeff asks, a little put out.

“No,” Claudia replies. “I never did.”

***

When Jeff’s breathing is even and steady, Claudia gets out of bed and pads softly out of the apartment and down the stairs. An inner door lets her into the bookshop which occupies the first floor of their home. She casts a quick glance around, the space slightly lit by the street lamp just outside. The bookcases which line the walls, the low shelves of toys and read-aloud books, everything is familiar and orderly and safe. She likes the shop best at night, when it is hers alone, when she doesn’t have to tolerate customers looking at the books, every one of which she has picked for a purpose, when she doesn’t have to see them be critical, dismissive, oblivious. In the day time, she takes over the office, the paperwork, the catalogs, and leaves the people part of things to Jeff.

With her office door closed and the light on, she opens a file drawer. She has come down here, she tells herself, for her collection of postcards, but now she looks first through the bundle of stuff from graduate school: old seminar papers, her doctoral dissertation in its dusty black binding. It is both familiar and strange to her, like a child sent away in infancy who has now found its way home, unexpectedly, to look at her with judging and neglected eyes.

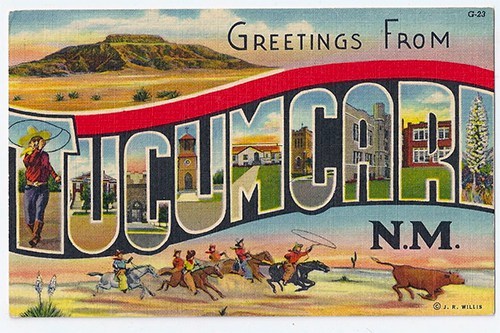

Claudia finds the bundle of postcards. On top is the one which had been pinned up over her desk for the whole five years of her graduate education: a card from Rodeo Bob’s Homestead Motel in Tucumcari, New Mexico, with a message printed carefully:

What is that degree worth once you got it?

Behind it is one postmarked the next day from The Breakfast Palace in Guadalupe, Arizona:

We must have had a real smart milkman.

***

In the morning the phone rings first thing when Claudia sits down to her desk in the shop. With a burst of Monday morning energy she snaps right to.

“Green Gables, Children’s Books.”

“Dr. Barton calling for Dr. Busacca,” says a secretarial voice.

“This is Claudia Busacca.”

“Hold please for Dr. Barton.”

She watches her fingers turn white on the receiver while she waits.

It is Daddy’s cardiologist; his report is short and very concise; she doesn’t understand a word. She asks him to start again.

“Maybe I’ve misunderstood,” Dr. Barton says to her. “Your father says you’re an MD?”

“No,” she says, and she finds herself smiling. “A Ph.D. But he thinks I should be allowed to practice medicine anyway.”

“Why yes,” Dr. Barton says. “That sounds like your father, now that you mention it.” He starts again, slower. Claudia tries to take notes, but after a while her pen slows, and then it stops.

***

Perched on the uncomfortable bed in her dorm room Claudia had called her father, some years ago, to tell him that she had passed her qualifying exams. “Highest honors,” she told him.

“What do they give you for that? Any cash?”

“No, Daddy, no cash.”

“You need some cash?”

“You got some extra you want to send me?”

He cleared his throat in a rush of satisfaction, always pleased when his children failed to ask for the things he wanted to give. He liked the challenge of forcing his good will on them.

“Put it aside for a new pick-up. Or maybe Joe needs it, if you got some extra this month,” Claudia suggested.

“Joe’s got a good job, tool and die is a good line,” her father reminded her.

“You want me to quit graduate school and learn how to cast drill bits?”

“I want you should be there when I die,” her father said. “Without me having to send you bus fare first.”

“I’ll just show them my diploma,” Claudia snapped back. “They let Ph.D.’s ride the bus for free.”

His laughter was hesitant, uneasy, and followed by a longer silence. “Well, I’ll just put a little something in the mail,” he said, finally. “You did a good job. Buy yourself a beer, celebrate.”

Her face hot with remorse and embarrassment, Claudia said: “Come on out here and drink that beer with me.”

“You find yourself a younger fella,” her father told her.

That night, in the bar in the basement of the graduate dorm, Claudia had met Jeff, who was wiry and very blond, who came from Baltimore where his mother, a widow, worked as a dispatcher for a trucking company, and who in four hours of intense conversation never once asked her what she was studying or who she was studying it with.

The next morning Claudia found a postcard pushed under her door, Scenic Trenton by Night, and on its back her first real message from Jeff:

I’ve been looking for a sane person willing to break out of this joint with me.

***

After Dr. Barton gives her all the details, Claudia sits at her desk for a long time, listening to Jeff consulting with a customer on the right books for a four year old. He is cordial but not familiar; he is knowledgeable but not overbearing. He sells a great many books to this concerned grandmother, all hardcover.

He comes into the office waving the charge slip over his head, a silly smile on his face. “Sneak literature into a daily diet of Ninja Turtles and get paid for it. Isn’t this better than four sections of freshman composition?” he asks.

Claudia doesn’t answer.

“Claudia?”

Claudia wants to talk to Jeff, to tell him the things she has just learned, to make the sounds and the words which will set things in motion, but she can’t.

But it doesn’t matter: without prompting, Jeff comes over and kneels beside the desk to put his arms around Claudia. The charge slip flutters, twisting to the ground: white, black, white, black.

He doesn’t watch to see it land, and Claudia remembers now why she married him.

***

The morning Claudia and Jeff got married in the campus chapel, Daddy had called at five a.m.

“Where are you?” she asked him, wide awake on the first ring.

“Where do you think? Annapolis. Joe can’t leave the base ’til six, we’ll have some breakfast, and get on the road,” he said. “You think we’d miss your wedding?”

“I think you’d be late for it,” Claudia replied.

“You worried I’m gonna embarrass you?”

Claudia thought of the wedding reception they had put together so carefully, the modest but elegant table of puff pastry and shrimp mousse, a sparkling wine which she could offer without wincing, mineral water with lemon, and a wedding cake layered with white chocolate and raspberries.

“Daddy,” she said. “Just don’t be late.”

Putting on her wedding dress, an eighty year old relic Claudia had labored over until it deserved to be called antique, all she could think of was Daddy and Joe, headed up Route 1 toward Philadelphia in her father’s pick-up truck, in a cab that smelled of peppermints and old vinyl.

A half an hour after the ceremony should have begun, Claudia stood in the vestry with the priest, still waiting for Daddy and Joe, watching a summer storm which had come up without warning. The wind rose cool; the rain was warm; the two hundred year old oak that stood just in front of the chapel was struck by lightning and came down, just like that, in a tremendous crack and a flurry of leaves. At that moment, her ears still ringing, Claudia saw the pick-up truck pull into the no-parking zone next to the library; Daddy climbed out in his dusky black suit, the same suit he himself had been married in, with Joe close behind in his sailor’s whites.

“What a strange pair,” the priest said, and then struck by an almost inadmissable thought, asked, hopefully: “That can’t be them?”

And Claudia was overwhelmed: by her anger at the priest who voiced so simply all the things she had been thinking; by her shame and frustration with her father and brother, who wandered toward them umbrella-less in the pouring rain, waving cheerfully as if they weren’t late at all, as if what these people thought of them really didn’t matter; and by the terrible clarity of her love for both of them.

Watching her father and brother coming toward her, picking their way delicately over the fallen braches of the oak tree, both of them dripping rain, an urge came upon Claudia, icy-cold and clear: they would pile back into the cab of the pick-up truck, all four of them, Jeff too, and take off down the road. They would forget the church, forget the priest, leave the guests to eat mousse and drink wine on their own while discussing formalism as interpretation and ideology, and with rain streaming over the windows the four of them would drive off for places unknown, unnamed, while Vicki Carr played endlessly on her father’s beloved eight track.

***

This time Claudia calls Joe before he can call her. He is agitated, up in arms that there is nothing more to be done.

“What about another surgery — what about a heart transplant?”

“Joe. He’s seventy-four. He’s at toxic levels on all his medications. He has diabetes, he has leukemia…”

“Leukemia! Since when does he have leukemia?”

“The doctor says it’s not unusual, at his age.”

He digests this in silence. Then: “So what do we do now? Can they give him anything, so he can breathe?”

“No,” Claudia says. “There’s nothing more to give him.”

Next, she calls her father, who wants to know exactly what the cardiologist had to say.

“What do you think he said?” she asks, and curses herself for a coward.

“Not much longer, huh?”

She forces herself to answer. “He says by the end of the summer.”

It is August 15.

***

Claudia and Jeff close the shop at 6:00 and trudge up the steps to home, continuing their discussion of inventory and airline schedules, temporary help and medicare, bookkeeping and cemetery plots.

The phone begins to ring as they open the door.

“I been thinking a lot about your mother,” Daddy says, as if they were picking up a conversation interrupted only by a trip to the bathroom.

“What about her?”

“The summer Joe came along, it was hot like this and she was so big with him. I used to go and get her New York Cherry ice cream. It was her favorite. I haven’t had New York Cherry ice cream in years and years. We sat out on the porch and ate ice cream until it was time to go to bed.”

“That’s probably why Joe was such a moose, Dad.”

He laughs, and then he tries to catch his breath. Claudia attempts to breath for him, across the telephone line. Then when things get under control, he starts talking again.

“I been thinking, Claudy. I never should have sold my pick-up.”

“No?” she says, wary now.

“Jerry down the street wants to sell his, it’s in good shape and he’s not asking too much…”

Next to Claudia, Jeff steps in closer, alarmed at the look on her face. She hushes him with an upheld palm.

“… for Seattle, the climate out there does me good. Get out on the road again on my own, I’ll be a whole new man.”

She feels the knot pull tight in herself and then she feels it break. “Don’t you dare,” she whispers. “Don’t you dare.”

“I just thought…”

“Dad,” she says, her voice rising sharp, her panic pushing out words she will live with forever, until she is old and desperate herself, and her father’s face has long since faded out of her memory. “You are being selfish and childish and foolish.”

“Maybe so,” he says, and hangs up the phone.

***

Jeff first suggests that Claudia call Joe, but when she rejects this out of hand and starts packing, he doesn’t argue with her. Instead, he calls the airline and makes a reservation on the next plane.

It gets her into Chicago at 11:35, thanks to the hour she’s gained flying west. The cabby has a skinny neck in a collar that is too big, large knuckled hands, a concave chest. Joseph Manginelli, his license medallion reads.

“My brother’s name is Joe,” Claudia tells him.

“Yeah? You a Dago? You look like a Dago.”

“Yeah,” Claudia says. “I’m a Dago.”

“So, you coming home from out of town?”

“I’m just in to see my Dad,” she says, her voice wobbling suddenly.

“Then he brought you up right,” the cabby says. “You come home to pay your respects. He brought you up right. I’ll bet he sent you away to school, you must be a lawyer, a doctor, something like that.”

“Something like that,” Claudia answers. Then she says, hopefully: “Do you know my Dad?” Claudia knows full well how ridiculous this question is, but she must ask it anyway. “Do you know Frank Busacca, used to sell Oldsmobiles on Lincoln Avenue at Northside Olds?”

Joe Manginelli shifts in his seat, flexes one hand and then puts it back on the steering wheel.

“No, can’t say that I do,” he answers. “Lotsa Dagos in this city. Your Dad sick, you coming home in the middle of the night?”

“He’s dying,” Claudia says.

He hands her a box of tissue over the seat. After a long time, when Claudia’s crying has subsided, he speaks again. “He might not say it to you when you get there, but you done the right thing,” the cabby says. “You remember that, when things get rough.”

***

Sometime later, the street lights begin to show Claudia familiar landmarks, and then she watches them go by her window: the boys’ club where Joe played softball all summer long, the church where they were both confirmed, the Katie’s Kwick Kut Beauty Parlor where her mother had her hair done every Friday afternoon. The Jewell Grocery looms up, brightly lit. She asks the cabby to pull over.

“The address you give me is still three blocks away,” he says.

“I got to get something,” Claudia says.

“You want me to wait for you? I’ll turn the meter off.”

“No,” Claudia says. “I want to walk from here.”

“Maybe the neighbors ain’t as friendly as they used to be.”

“So who is?” Claudia smiles at him.

She finds the ice cream and then heads for home, the brown paper bag tucked into the crook of her arm, her suitcase in her other hand. At the flat, she fumbles for a minute with her keys, and her father opens the door for her.

“What’s that?” he asks, not in the least surprised to see her.

“Ice cream. They didn’t have New York Cherry, so I got you Peaches and Cream.”

“No salt, no liquid,” he recites.

“What’s the matter?” Claudia says, her voice steady but her hands shaking. “You don’t want to have any fun?”

***

That night, Claudia sleeps in her girl’s bed. She dreams of her father in an old pick-up truck. Together they are driving down a two-lane highway, the breeze washing through the open windows. This isn’t the way they planned to go, but it doesn’t seem to matter much; they drive on anyway. Sitting sideways on the bench seat, Claudia is content to watch her father grow younger with every mile, his hair darkening, his spine lengthening and straightening, his muscles gaining strength and definition, his eyes growing bright and his face smooth, until they look like brother and sister, until they are of the same age.

***

Claudia wakes long past ten; she stumbles out of her room into an empty kitchen. She knows without looking that her father is not in the apartment, that she is alone.

She tries to stay busy. She makes toast of Roman Meal bread, she puts the chipped saucer with its lump of margarine on the table, she makes coffee in the little aluminum pot. Over the sink her father has put up an index card with a thumb tack, on it he has printed No Liquids That Means Water. But Claudia goes to the freezer anyway. She gets out the icecream, which she puts on a plate of its own in the middle of the table.

Finally she sits down at the table. The grey-marbled formica is slightly tacky, her bare forearms peel away from it reluctantly when she reaches for the sugar.

The kitchen smells of olive oil and frying peppers, stale sponges and old newspapers.

She butters her toast.

The phone rings and she jumps as if bitten.

“Hello?” she says, snatching the telephone from the wall in an awkward swoop. “Daddy?”

“You know,” her father’s voice answers her. “When you and Jeff bought that bookstore I thought, all that schooling, to sell kids books.”

“Daddy? Daddy?” Claudia’s voice catches. “Where are you?”

“I mean, you could a done that here at home, you didn’t need to go to graduate school for that.”

This causes her to pull up suddenly. “I thought you were glad the shop was doing so well.”

His breathing is hoarse and shallow. “I wanted you to be a professor, like you studied for.”

Claudia leans against the kitchen wall, bound to it by the kinked and coiled cord of the telephone.

“Where are you?” she whispers.

“Schneider’s.”

Claudia has an immediate picture of him at the long, polished wood of the bar, hunched over on his stool, the ancient black telephone, its handset crusty with old spittle, cradled against his cheek. The only sentence which seems to live in Claudia’s mind comes out of her mouth. “How is Mr. Schneider?”

“Good. Monty’s good.”

“What about Mrs. Schneider?” she asks.

“Gloria’s gone,” her father says.

“Oh. Cancer?”

“Nah,” Dad says. “The guy who refilled the cigarette machine, she took off with him last month.”

The laughter which bursts out of Claudia causes her physical pain. She slides down the wall to sit curled on the floor, her knees hugged in to her chest, and laughs until her voice is hoarse.

When her father comes through the door a half an hour later, thirty minutes to walk two blocks, winded, his face the color of sour milk, his lips almost blue, she is still against the wall, her arms slung around her knees.

He falls into a chair, gasping. His hair stands up in spikes over a face which has been sucked dry, all loose skin and dewlaps, a rim of red under each eye. But he is neatly dressed: his shirt is clean and ironed, his shoes are polished. He has supplemented his suspenders with a piece of string through his belt loops to hold the folds of excess material in place.

“You need a belt,” Claudia tells her father, when his breathing has steadied. When it is clear that he will continue to breathe.

“Waste of money,” he whispers, and he starts to take pills out of the collection of bottles on the kitchen table to line them up in a row.

Claudia waits a while; when it is clear he has nothing more to say, she begins. “You never told me that, back then,” she says to him. “You never said a word about what I did with my degree.”

The fan hums to them as it continues on its arc through the room, casting a breeze which is gone before it gives any relief.

“You didn’t need me to tell you,” he lifts one shoulder, impatient. “Your brother, now, you gotta point things out to Joe. He’s like your mother.”

Claudia is suddenly short of breath. “Who am I like?” she asks; her voice sounds high and far away, a stranger’s voice, a little girl’s voice.

Her father spoons into the melting icecream and then sticks his pills, two small red ones, a yellow one, three white ones, into the swirl of bone white and neon peach.

“Not like your mother,” he says.

“Who am I like?” Claudia asks again, her forehead on her knees.

“You’re your father’s daughter,” he says. “No question.”

The linoleum is a brittle, speckled yellow; Claudia counts the red and green and blue drops that fall between her bare feet. When she is finally able to lift her head, she sees her father bend down to his spoon to sip softly at the icecream.

Then he says: “I bought the pick-up truck.”

From his shirt pocket he takes out a worn key on a tarnished metal ring. He looks down at the key in his palm quizzically, as if he is not sure himself what door it might unlock.

“How about we take a drive out into the country,” he asks.

Claudia responds: “I’m driving.”

Her father shrugs. “Whatever you want,” he says. “What ever makes you happy.”

He tosses the key to Claudia; she catches it with her upheld hand.

June 14, 2017

A Manhattan You Won’t Recognize

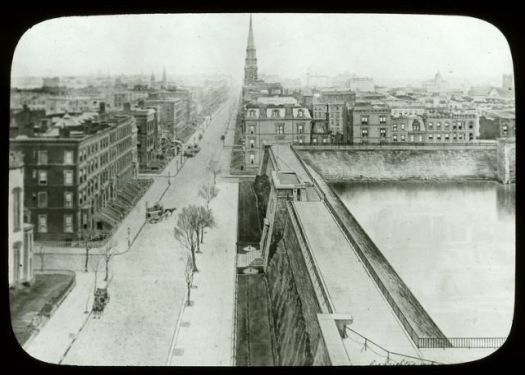

If you could step into a time machine and go back to Manhattan in 1884, this is what you’d find where today the New York Public Library stands.

The Croton Distributing Reservoir was the above-ground reservoir at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue that provided the city’s drinking water for much of the 19th century. From Wikipedia: “The reservoir was a man-made lake 4 acres (16,000 m2) in area, surrounded by massive, 50-foot (15 m) high, 25-foot (7.6 m) thick granite walls. Its facade was done in a vaguely Egyptian style.”

The reservoir was a favorite destination for tourists because the view from the promenade was excellent:

In 1844 Edgar Allen Poe recommended the promenade:

When you visit Gotham, you should ride out Fifth Avenue, as far as the distributing reservoir, near Forty-third Street, I believe. The prospect from the walk around the reservoir is particularly beautiful. You can see, from this elevation, the north reservoir at Yorkville; the whole city to the Battery; and a large portion of the harbor, and long reaches of the Hudson and East Rivers.

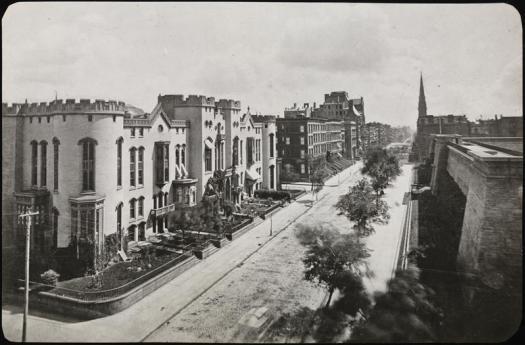

Just across from the reservoir on Fifth Avenue was Rutger’s Female College, which was founded about 1840 (as a female ‘institute’) on the lower east side.

Looking south on Fifth Avenue

Looking south on Fifth AvenueIn 1860 the institution was upgraded to a college and moved to the buildings at 487-491 Fifth Avenue, built in 1856 as an early attempt at luxury apartments.

Sophie and Anna of The Gilded Hour attended Rutgers Female College.

June 7, 2017

so long, bluehost

I’m in the process of switching to a new webhost, which means that things will be wonky here for the next one or two days. Just a heads-up.

June 6, 2017

The Gilded Hour and Its Sequel

I know, you want the next book yesterday. I know. I would love to have finished it already, but: not yet.

Have a look at this in the meantime. It comes from Electric Lit, and it makes me feel a whole lot better. Maybe not you so much, but me. And that means I can write more easily.

click for dull size image

click for dull size image

crazy all the time: writers

Here’s the thing about writing, especially writing fiction: You do it alone. In your head, sitting by yourself, your mind splits itself into three or ten or a hundred personas. These characters talk to each other, conflicts blossom and a story takes root and grows. If writing is going well, you lose time. You fold in on yourself and disappear into your own mind. Your subconscious becomes superconscious. When you come back into the world, you may be surprised to see that it’s raining. Or the sun has set. Or the dog has peed in your slipper.

The kind of focus that generates a story comes easily to a few writers, less easily to most of us who write. Solitude — the ability to isolate oneself, to live inside the mind — is what makes writing possible. So it makes sense that authors tend to be introverts, but even for those of us who are introverted by nature, the necessary mindset is often elusive. Some writers are so desperate for solitude, so frantic for focus that they’ll go to great lengths to impose it on themselves.

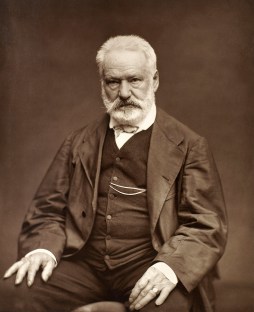

Victor Hugo. Imagine him naked.

Victor Hugo. Imagine him naked.Demosthenes, an Athenian orator and contemporary of Plato and Aristotle, shaved half his head so he’d be too embarrassed to leave home.

Maya Angelou shut herself into a hotel room and wouldn’t allow housekeeping in until things got fragrant.

Victor Hugo had his servant hide all his clothes and wrote naked to stay focused — and in the house.

Friedrich Schiller had to have a desk drawer full of rotting apples in order to focus on writing.

Dickens had nine little objects that had to be on his desk when he wrote, including a figurine of a dog fancier surrounded by puppies.

Here’s a question that might occur to a logical, impartial observer of writers: if you must have solitude to write, but the getting of solitude is so difficult, why? Why write? Why are so many people enamored of the idea? Scratch a plumber, a pediatrician, a tug-boat pilot, and a would-be novelist emerges. Any traditionally published writer is aware of this, because the plumber, pediatrician and tug-boat pilot have said as much, to his face. What is less clear to me personally is if the people who are so enamored of the idea know what they’re getting into. From all different angles, do they have any idea?

I have no research to back this up, but I have the strong impression that many people want to see in themselves the next millionaire author. My first bit of advice: If you really want to write, make sure you’re not doing it just for the money.

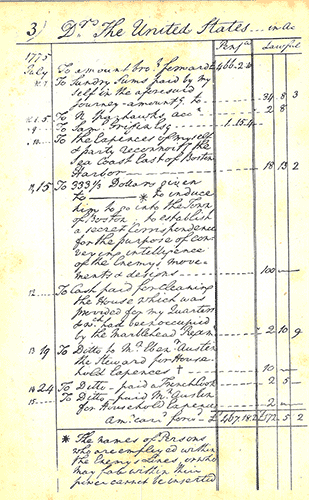

The Authors Guild published results of a study on author income in 2015 (you can download the pdf here) with some unhappy truths: the majority of authors earn below the poverty line. Worse than that: Since 2009 authors are earning less, and because the Authors Guild wants you to understand what that means, they provide this graphic:

click for a larger image

click for a larger imageIf writing were easy, maybe people would do it for fun. But it isn’t easy, as Orwell points out in his usual forthright way:

All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.George Orwell

Consider the conundrum basic to the pursuit of publication: The writer is (most usually) an introvert with a goal. The end result of all her solitary inward-turned creative endeavor is a story, and stories require an audience. You need solitude, and you need an audience. There’s a disconnect there. A built in neurosis, which can be defined very simply as ‘arising out of inner conflict.’

There are a couple ways to get an audience. You send out your stories to friends and family; you join a critique group, you post your work online. And this may be enough of an audience for you. You’re not worried about getting paid; you just want to be heard. If you do want to earn a living writing, your options are narrow. You find a traditional publisher, or you self publish. Either of these options presents you with a conundrum. You need solitude to write, but the publishing business seems designed to deny you the solitude and peace of mind you need.

In the film Stranger than Fiction, Emma Thompson is a novelist in a deep rut and unable to finish her overdue work. Her publisher sends her an assistant: confidante, cheerleader, mentor, played by Queen Latifah. Quick hint: this doesn’t happen. If you can pay for this kind of help yourself, great; otherwise, don’t hold your breath.

In the film Stranger than Fiction, Emma Thompson is a novelist in a deep rut and unable to finish her overdue work. Her publisher sends her an assistant: confidante, cheerleader, mentor, played by Queen Latifah. Quick hint: this doesn’t happen. If you can pay for this kind of help yourself, great; otherwise, don’t hold your breath.There are writers successful enough to afford publicists and marketing experts and others who will shield you from the crass side of getting a book out there, but most of us aren’t in that crowd. In the here and now, a writer who wants to be published has to interact with a wide variety of people. Agents, editors, and all the dozens of people who are involved in getting a book out to the public. A good agent will run interference, but s/he can’t play the game for you. Then, in the current market, you find yourself dealing with bookstore owners and clerks, book reviewers, book group coordinators, social media groups, and readers.

I hear you asking: what about your editor? That assumes (1) that the novel is already under contract and your editor isn’t juggling 20+ authors and novels and has nothing better to do than to sit down with you over a long lunch twice a week; or (2) that you’ve hired a private editor (again: refer to the diagram above). So the answer: you need other writers, people who understand the process, who know something about plot structure and point of view.

Finding a writing group is not easy. We need each other, but we’re introverts, we’re anxious, we’re underpaid, and we’re creatives with egos. Let’s say you have found the right group, people who are at approximately your same skill level and you all click, you get and give solid feedback, the feedback helps you polish your work, and your epic novel (on the colonization of Mars, or twin sisters in a death battle over an inheritance, or a depressed teenager) starts to come together. In the modern day you have two choices: you can try to find an agent who will try to find the right editor and publishing house, or you can self publish. And this is where the real crazy starts.

It doesn’t matter which route you go, it’s crazy all the way. Even before the 2008 crash publishing was as stable as a drunken sailor; since that point it is more like the shuffleboard court on the Titanic. On top of that, the new technologies have created a crisis that will take another twenty years to sort itself out. Unfortunately, we — you and I — we live in the here and now. This is our circus. These are our monkeys.

The truth is that publishers are terrible business people who indulge in a lot of magical thinking. They buy hundreds and hundreds of novels every year and toss them (and their authors) carelessly onto ever-more-crowded world stage. Introverted people who are most comfortable, who actually need solitude to create their work are pushed into this chaos. Today it’s not enough to write; even if you have a traditional publisher, you have to take responsibility for your novel’s success, and that means either hiring professionals, if you have 25K or so extra lying around, or teaching yourself how to do it. Which is a drain on your mindset and sense of self and the solitude you need.

Your writing will suffer for your writing.

Speaking to a group of college students, Hunter S. Thompson said, “I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me.”Is it any wonder that writers tend to depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder? That a good number of us self medicate with drugs and alcohol? F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote to Ernest Hemingway about his troubling reliance on alcohol. Hemingway wrote back: “Of course you’re a rummy. But no more than most good writers are.” The writers who gathered for lunch at the Algonquin round table — what they referred to as their vicious circle — embraced their excesses. Dorothy Parker, the quickest of the wits, had a serious alcohol problem but played it for laughs with bon mots like “I’d rather have a bottle in front of me, than a frontal lobotomy.”

There are legions of stories about hard drinking writers sitting together, talking about writing and stories and human nature. Because writers in this situation are often drinking and because they are introverts and prone to depression, they get into arguments and, sometimes, fist fights. The worst of that generation was Norman Mailer, who head butted Gore Vidal right before they were supposed to walk onto the Merv Griffin show together.

Mailer acted out before that term had any currency. He once tried to bite an actor’s ear off, he regularly punched people in the face, stabbed not one but two wives, and got away with it. Mailer was a violent alcoholic who could tell a story. Underneath the crazy he may have been a traumatized and depressed introvert. Or he may have been a narcissistic self indulgent sociopath and ass.

The worst writer craziness has to do with alcohol and drugs, but not all of it. A large proportion of our kindred suffer from bipolar disorder as well as depression. Robert Frost was a depressed introvert, possibly bipolar, and according to Wallace Stegner, a prima donna. He demonstrated that nicely one year at the Breadloaf Writers Conference. While the poet Archibald MacLeish was giving a reading, Frost started a fire in the back of the room. Just a little fire. Easily put out. So MacLeish did not stop the reading, and Frost stormed out in a huff.

To this point I’ve been focusing on traditional publishing, but there’s just as much, if not more, craziness in the newer world of epublishing. At first glance it seems like a good idea: cut out the middle man, those publishers who are great at gatekeeping, but not so good at tending their own gardens. The problem: cutting out one middle man just leaves a hole, and in the way of all things, vacuums get filled, these days, mostly by Amazon. And by scam artists. People who want to teach you how to be a self published success. For a price.

Of course, they haven’t done it themselves, but they can do it for you. Log into any social media site and identify yourself as a writer, and you will get to know these people right away.

Those who write and want to be published are vulnerable. They are driven, and needy, and clueless, lambs to the slaughter. Even experienced people who should know better are so desperate for a way into publishing that they fall for these scams. I personally know a physician who was writing a medical thriller, an extremely intelligent, successful woman at the top of her field. She was so focused on this novel, on the acknowledgement that it would bring her, that all common sense went out the window and she paid out some five hundred dollars to one of those online organizations who will so gladly show you the way.

She would never fall for somebody trying to sell her aluminum siding, or for a down-on-his-luck Nigerian prince who writes pathetic emails. But she did fall for somebody who recognizes her wish to be an indie published writer, and that person goes in for the kill. I would call that crazy behavior on her part, but it’s understandable, how it happens.

Google the phrase “self publish my novel” and you’ll get 3,940,000 hits in a matter of seconds.

I have been pondering this nuttiness for most of my adult life. As it turns out, there is, I think, a fairly simple answer. This quote is from Jhumpa Lahiri:

It was not in my nature to be an assertive person. I was used to looking to others for guidance, for influence, sometimes for the most basic cues of life. And yet writing stories is one of the most assertive things a person can do. Fiction is an act of willfulness, a deliberate effort to reconceive, to rearrange, to reconstitute nothing short of reality itself. Even among the most reluctant and doubtful of writers, this willfulness must emerge. Being a writer means taking the leap from listening to saying, ‘Listen to me’.”

Of course at this point you have to consider Hemingway. He yelled ‘Listen to me’ and people listened. The whole western world listened. And still he ended his own life, as successful and well received as he was. Maybe people tell stories and work to get them published because they want to be heard, or maybe that’s just one small part of the larger mystery of why we do what we do. Certainly for Hemingway, being heard was not enough.

So you have to ask yourself, will you be satisfied with being heard by what will probably be a fairly small circle of people, for little monetary return? Are you willing to invest not just your mind but your peace of mind? If so, then arm yourself, and sally forth. I look forward to reading your novel.

May 26, 2017

19th century household hints: from bedbugs to hartshorn

I’m always running into terms which stump me while reading 19th century newspapers and articles. You can look things up, of course, but what we now understand under ‘hartshorn’ may have changed a lot since the 1880s.

The best source for information on 19th century terms, especially when it comes to housekeeping and medicine (in my experience) is archive.org, where out of print works are made available to read online. And the technology is very good. You can search for terms inside books, read page by page on line, or download entire volumes.

These sources are valuable for a wide range of reasons, only one of which is the cost: nothing. This becomes significant when you look at contemporary scholarly studies of the same subject, for example The Objects and Textures of Everyday Life in Imperial Britain (Amazon link) which looks very interesting, but not so interesting that I’ll pay $150 for 244 pages. This is the problem with scholarly publications.

Here is a list of books on housekeeping that you can consult online and I have found useful. So for example, when it occurred to me that in the 1880s they may not have used the word ‘armoire’ I started with a general Google search, went on to look at websites that specialize in antiques, and ended up at archive.org to see how ‘armoire’ ‘wardrobe’ and ‘dresser’ were used. I found what I needed. If not I would have gone on to search novels written in the 1880s for these words.

Here is a list of books on housekeeping that you can consult online and I have found useful. So for example, when it occurred to me that in the 1880s they may not have used the word ‘armoire’ I started with a general Google search, went on to look at websites that specialize in antiques, and ended up at archive.org to see how ‘armoire’ ‘wardrobe’ and ‘dresser’ were used. I found what I needed. If not I would have gone on to search novels written in the 1880s for these words.

The housewife’s library. George A. Peltz. 1883.

Housekeeping and home-making, with chapters on dress and gossip. Marion Harland. 1883.

click for a larger image

click for a larger imageA domestic cyclopædia of practical information. Todd S. Goodholme. 1878.

Miss Leslie’s lady’s house-book; a manual of domestic economy containing approved directions for [everything] (also available at hathitrust, another great place for reference works). Eliza Leslie. 1869.

Another book which would be extremely useful but is not available online (if you find it somewhere in the ether, please let me know) is this gem:

The Art of Housekeeping: a Bridal Garland. M.E. Haweis. 1889.

I saw Mrs. Hawais’s title quoted in Inside the Victorian Home: A Portrait of Domestic Life in Victorian England, by Judith Flanders (out of print, but readily available for a few dollars, used) on the subject of bedbugs, which were not to be expected in decent bedrooms, according to Mrs. Hawais, but might be imported unwittingly from cab, omnibus or train.

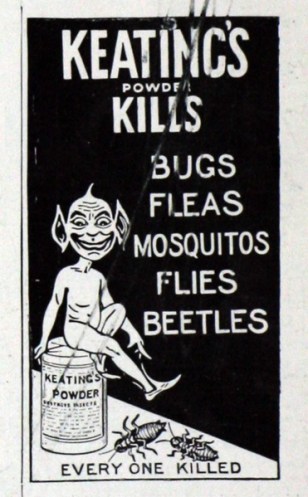

Keating’s Power

Keating’s PowerOne technique for dealing with bedbugs was to call a carpenter in the spring, who would take all the beds outside, dismantle them, scrub every piece with calcium hypochlorite and then douse it all with Keating’s powder (a pyrethrum-based insecticide). Sometimes this had to be more than once.

I realize that my fascination with the details of 19th century life might strike you as somewhat odd, but I yam what I yam. And I write about these things, so there’s an upside.

May 24, 2017

If you write fiction

….or want to write fiction, or are interested in the process of writing fiction:

….or want to write fiction, or are interested in the process of writing fiction:

Insomnia drove me to do some work, but weariness kept me from actually writing. So I spent an hour going through old posts on craft (plot, pov, characterization, etc etc), and I’ve organized them into something I hope is usable.

It’s incomplete, but it’s a start.

You’ll find the index to these posts under “writing and craft” in the menu just under the top banner. Please let me know if you run into any problems.

May 17, 2017

Why Anna and Sophie have chapped hands

In the 19th century the most important advance in medical science was called (at the time) Listerism. Simply put, Joseph Lister, working with Louis Pasteur’s advances in microbiology and the discovery that bacteria cause putrefaction and infection, came to a conclusion: In a medical setting the first line of defense is to keep the patient isolated from all such bacterial agents. There were two ways to achieve this: Antisepsis (using chemicals, usually carbolic) or asepsis (using heat) to sterilize. In 1881 John Tyndall wrote

Living germs … are the causes of putrefaction. Lister extended the generalization of Schwann from dead matter to living matter, and by this apparently simple step revolutionized the art of surgery. He changed it, in fact, from an art into a science.

In 1876 Lister came to the U.S. to lecture about his findings.

In 1878 Dr. Lewis Stimson performed the first demonstration of an antiseptic surgery in the United States, using Lister’s antiseptic technique while amputating a leg.

In 1881 President Garfield died not from the bullet fired by an assassin but because the physicians treating him rejected Listerism and caused massive, systemic infection by probing his wounds with unsterilized instruments and dirty hands.

As the summer waned, Garfield was suffering from a scorching fever, relentless chills, and increasing confusion. The doctors tortured the president with more digital probing and many surgical attempts to widen the three-inch deep wound into a 20-inch-long incision, beginning at his ribs and extending to his groin. It soon became a super-infected, pus-ridden, gash of human flesh.

This assault and its aftercare probably led to an overwhelming infection known as sepsis, from the Greek verb, “to rot.” It is a total body inflammatory response to an overwhelming infection that almost always ends badly — the organs of the body simply quit working. The doctors’ dirty hands and fingers are often blamed as the vehicle that imported the infection into the body. But given that Garfield was a surgical and gunshot-wound patient in the germ-ridden, dirty Gilded Age, a period when many doctors still laughed at germ theory, there might have been many other sources of infection as well (Markel).

At least some people were paying attention, because in 1883 Dr. Stimson was asked to operate on former President Grant’s leg.

This photo was taken in the surgical amphitheater at Bellevue in the early 1880s. By modern standards it’s shocking (note especially the bloody floor), but it should have also been shocking to physicians in 1880. I’m sure medical historians have written about the factors that led American physicians to reject the findings of Pasteur and Lister, but my guess is that it was simple hubris.

Because there were physicians and surgeons who accepted scientific findings and practiced antisepsis and asepsis, I felt justified in having Anna and Sophie act like sensible human beings and wash their hands. And instruments. And everything else. In carbolic.

Cheyne, W. W. Antiseptic surgery: its principles, practice, history and results, London 1882.

Kessin, Richard H. and Kenneth A. Forde. “How Antiseptic Surgery Arrived in America.” P&S 2007. link.

Markel, Howard. The dirty, painful death of President James A. Garfield. PBS, September 16, 2016. link

Pennington, T. H. “Listerism, its Decline and its Persistence: The introduction of aseptic surgical techniques in three British teaching hospitals, 1890–99.” Medical history 39.01 (1995): 35-60.

Tyndall, J. Essays on the floating-matter of the air. London, 1881.

May 16, 2017

Keel boats & Jemima

I had a letter from Janet with a couple questions about the Wilderness novels:

I have really enjoyed all your books, However, there are a few points here and there that have puzzled me. First, in Endless Forest, I don\’t understand why Callie and Ethan think Jemima could possibly have a legal claim on the orchard. Didn’t she steal the deed and sell it off to that preacher? Callie bought it back and presumably has the documents to prove it, so she didn\’t inherit it from Nicholas. I would think that would put and end to all claims from Jemima. Any inheritance claims by her son would be on the money Jemima realized from the sale (presumably spent).

One more thing– in Queen of Swords, how could Nathaniel and Bears possibly get to New Orleans by river in only two months It would take them at least two weeks to get to Pittsburgh and about 12 weeks to get down the Ohio (contemporary accounts give that as the time by steamboat, much less keelboat). Add another few weeks to get down the Mississippi and that puts the journey at a minimum of four months.

It’s always interesting to get questions like this because my first reaction is to panic, and then, almost always, I figure it out and can stop panicking.

First, regarding Jemima. She did indeed sell the orchard to the preacher. Then his nephew tried to assault Lily, and to keep the kid out of jail, he sold it back for a pittance. The town made a collection to make sure Callie would get it back.

Maybe Jemima wouldn’t have succeeding in taking the orchard away from her daughter, but she could have made life miserable while she tried, and dragged it out as long as possible.

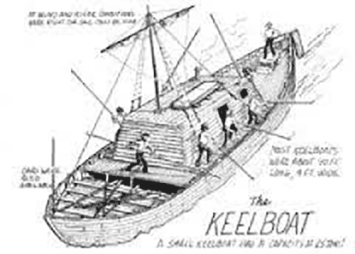

Drawing by John Russell

Drawing by John RussellThe more interesting question is the travel time from Paradise to New Orleans. Generally how I research things like this is to consult travel diaries of the period as well as timetables — sometimes they are still available — from commercial transport companies. I vaguely remember looking through material on traveling south on the Mississippi, but the details are hazy. I’ll have to dig back through my notes to figure it out again. I do remember some interesting trivia: a keelboat that traveled down the Mississippi to New Orleans was usually broken up for firewood, because there was no good way to get it back where it came from.

Here’s one short article on transport before steam.

Here’s a really interesting article about the Army’s reconstruction of Lewis and Clark’s travel by keelboat by John Russell

So again, I’m happy to answer questions. Sometime I’ll have to go through and tag the posts with questions that people ask about most. Ethan and Callie’s relationship is one of them. And then there was the unforgettable letter from Miss Middleton.

Of course, sometimes I do get things wrong. I’m only human.

May 14, 2017

old mothers

East Friesland

East FrieslandSo, mother’s day.

The farthest back I can trace my maternal line is six generations.

I give you Rixte Margrethe Tjarcks born 1732 in East Friesland on the Dutch border, died June 1795 in the village of Aurich.

This is not a drawing of Rixte, but it could be. Right time period, right part of the world. And yes, her name is unusual for us, but it was actually quite tame for her time and place.

East Friesland