Kyle Michel Sullivan's Blog: https://www.myirishnovel.com/, page 50

April 25, 2024

Stupid Blinders on...

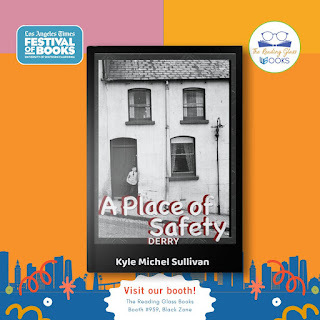

Damn, I just remembered the LA Times Festival of Books was last weekend. I got so caught up in working on NWFO, APoS-Derry got ignored -- and it was on display there. Shit. Here are some images of it...but now I feel rotten that I didn't make use of this to get interest drummed up.

Damn, I just remembered the LA Times Festival of Books was last weekend. I got so caught up in working on NWFO, APoS-Derry got ignored -- and it was on display there. Shit. Here are some images of it...but now I feel rotten that I didn't make use of this to get interest drummed up.I really suck at publicity and promotion. I've never been good at it. That's one of the reasons I was never able to get my screenplays off the ground -- no ability to sell them. Hell, 90% of Hollywood is selling. Yourself. Your product. Your ability. And even then, you have to be supremely good at it.

Despite the fact that your product or abilities are only 5% of the equation, really. A friend of mine is an award-winning DP (we're talking MTV Music Award for Cinematography) who is an artist on film in his use of light, color and shadow. And he has to fight to get work. I'm nowhere near the same level of ability as him, so I'd have to push 2-3 times harder...and it's just not in me.

So I fucking blew it with APoS-Derry. And I feel like shit about it. But there isn't much I can do, now. I'm so deep into debt, and I've spent so damn much on pushing the book. I have to keep in mind, I'll be doing that, again, with NWFO. But I'm not seeing the return I need to justify it.

So I fucking blew it with APoS-Derry. And I feel like shit about it. But there isn't much I can do, now. I'm so deep into debt, and I've spent so damn much on pushing the book. I have to keep in mind, I'll be doing that, again, with NWFO. But I'm not seeing the return I need to justify it.But I have to. Somehow, I'll have to find a way to keep it going...including with volume 3, Home Not Home.

At least I'm closing in on finishing draft 9.

April 24, 2024

60%

Just 40% left to input. I'm still rewriting from the red pen notes and characters are sharpening themselves. Like Evangelyne, who becomes angry with Brendan when it looks like he's trying to be her knight in shining armor against a racist sales clerk. She gets huffy if she thinks someone feels she can't handle herself and needs protecting.

Just 40% left to input. I'm still rewriting from the red pen notes and characters are sharpening themselves. Like Evangelyne, who becomes angry with Brendan when it looks like he's trying to be her knight in shining armor against a racist sales clerk. She gets huffy if she thinks someone feels she can't handle herself and needs protecting.They have a quiet argument in the middle of The Galleria before she realizes Brendan is completely confused about the problem. I'd had it wind back around to him not being able to return to Derry, but then just cut anything that alluded to his past and kept it focused on Vangie misreading his meaning when he barked at the clerk. They'd been insulting to him, as well.

Vangie knows her own value and has no doubts about herself. He does not know his, except when it comes to repairing things. Which is brought home to him when he sees how Everett is, regarding his artistic ability. The man has zero self-confidence, despite doing two elegant portraits -- 1 of Brendan and 1 of Aunt Mari's family. Even the B-girls like what he did.

This gets Brendan to thinking he wants to change the way he sees life and deepen his existence. Not be alone. Not be afraid to do something new, like learn a new language. For no more reason than just to do it.

I may be reading more into my writing than I think, but I like this idea of what I think it is.

April 23, 2024

April 28th

That's the day I need to have this draft of NWFO done so I can send it out for proofing and editing. April 30th, I'm off to Rhode Island to oversee a pickup, then May 5th I'm running to Dallas, San Francisco and Sacramento for other packing jobs. So I won't have the time I need to work on it till after...and that'd make things too tight to make my deadline.

I'm going to make it. I'm about 40% done...up to the chapter where Brendan nearly kills a man, then freaks out at realizing how easily he could have done it. No hesitation on his part.

I'm going to make it. I'm about 40% done...up to the chapter where Brendan nearly kills a man, then freaks out at realizing how easily he could have done it. No hesitation on his part.That sort of ties into his thoughts when he and Scott are discussing the mass murders committed by Dean Corll and Elmer Wayne Henley. Scott insists there has to be a reason or explanation that will help people understand why Henley and David Brooks would take male friends of theirs to Corll to be raped and killed.

Brendan points out they were just guys being paid -- money, car, drugs -- and there's something in many people where self-interest takes over and concerns for others vanish. He saw that happen in Derry, with Billy helping his uncle prepare for the attack on the People's Democracy marchers at Burntollet Bridge, and Colm casually helping kneecap Paidrig, who'd been his buddy since before he met Brendan, all over cigarettes.

Scott insists there has to be some existential cause but to Brendan it's just immediate circumstances and luck of the draw. If during Bloody Sunday he'd moved an inch to the left, he'd have been killed by a soldier instead of just hit by shrapnel. And the Paratroopers had stormed into the anti-internment march with live ammunition in their weapons, ready to commit slaughter.

So now he's nearly killed a man he didn't even know in order to protect someone he did know, and it emphasizes his belief that circumstances are what count all too often in all too many situations, not deliberate thought.

Because if he had thought through him defending that friend, he'd only have used a baseball bat to crack the attacker's knees, thus stopping him, instead of aiming for his head.

April 22, 2024

My ways is slow...

I'm slowly digging through and have managed four more chapters, one of which wound up with a bit more restructuring and rewriting than I expected. It's setting up how Brendan and Jeremy will wind up being good friends after he returns from the Yom Kippur war.

Turns out Jeremy was talked into going to a kibbutz for a year, by his rabbi. Of course, his family happily goes along with it, so he feels like he has no choice but to do as they want.

Turns out Jeremy was talked into going to a kibbutz for a year, by his rabbi. Of course, his family happily goes along with it, so he feels like he has no choice but to do as they want.This popped up while I was redoing a lazy summer afternoon between Brendan, Scott and Jeremy, in the pool. In Houston, summers are brutally hot and humid. Which Brendan doesn't like. But having the pool to help him deal with it becomes a mainstay of his existence.

Initially, I'd written the scene as an earlier one Brendan was remembering, but I chucked that and made it current. There's tension between him and Scott, who was moved out of the pool house so Brendan could live there. Aunt Mari wants Brendan to remain close to the family, and this is how she manages it after the B-girls caused a situation that makes him want to leave.

So Scott is snarky with Brendan as he floats around the pool, but Brendan ignores him. Jeremy notices and winds up confiding his reluctance about the trip to Brendan while Scott is out of earshot.

Then during Hanukkah, Jeremy makes a short visit home with a couple of IDF buddies. Brendan sees he is unsettled, jittery, and having trouble being around his family, so he trusts Jeremy enough to let him have his one joint, to share with the guys. To settle them. Which it does.

And step by step, he and Jeremy wind up being more like brothers than any of his actual brothers. this was not specifically planned, but I'm liking it.

April 21, 2024

Old habits and all that shit...

As I go through NWFO and input the red pen edits, I'm also still adjusting the language and tightening up the structure. I've compared my writing to peeling an onion, before, but it really is like that. Each draft is one more layer gone until I get it down to the point where I am about to wind up with nothing.

As I go through NWFO and input the red pen edits, I'm also still adjusting the language and tightening up the structure. I've compared my writing to peeling an onion, before, but it really is like that. Each draft is one more layer gone until I get it down to the point where I am about to wind up with nothing.I'm removing as many softening words or tentative conjugations as I can. Less of the it seemed kind of writing and more of the it was. Also turning I was running into I ran. Make everything more immediate for Brendan's telling. Tighter. Cleaner.

I'm currently reading The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize winner...a chapter at a time as I do my business on the toilet. It's taken me some time to get into the book, and I like Joe Kavalier more than Sammy Clay, so far, but it's started me thinking about something.

The writing style does not seem to fit the story, to me. Chabon's prose is very busy and rich and erudite, with a couple words I had to look up. Which surprised me, because I like to think of myself as somewhat educated with a good vocabulary. But that's what clued me in.

Joe is a Jewish boy who's escaped from Prague after the Anschluss. Sammy is his cousin, in Brooklyn, who's always trying to find an angle. It's weird, but the writing of their stories is...I dunno how to put it...too rich for their backgrounds, so far. It's told in 3rd person omniscient, so it's not like the boys are using words and phrases they wouldn't yet know, but it doesn't match them.

I'm thinking of another Pulitzer Prize winner -- Lonesome Dove -- in comparison. Larry McMurtry's style is simple and direct, like his characters, Gus and Call. And Alice Walker's style in The Color Purple fits Celie perfectly. But that of another Pulitzer winner -- Trust -- was so dry and removed from the characters I could not connect with them; it was like I was reading an outline for the book and characters instead of following their stories. And A Confederacy of Dunces was working so hard at being unusual it became impossible.

I like to think the style I have in APoS-Derry and NWFO reflects well on Brendan, which is probably easier to get away with because it's being told in 1st person. Won't know till I'm done.

April 20, 2024

Started in on the final draft...

I know I've said this, before, but this is the final draft of A Place of Safety-New World For Old. I might make corrections for typos or missing words and the like, but no more restructuring. It's time to let go. I could work on this book until I was dead, and considering how old I am that wouldn't be all that much longer. But I think 20+ years is sufficient time to write a novel regarding something you know nothing about.

I'm doing this draft on the PC, as mentioned before, and it's helping. I've found more errors, and Word for PC is more of a Grammar Nazi, so I'm having to justify my own use of punctuation and sentence structure. Not what I expected. At least it's making me think of what I'm doing.

Responses to my initial book cover design are...interesting. It's another case of taking me outside my box and making me justify my decisions while causing me to think up other options. I've been scribbling out some other layouts, but those seem busy. I like the simplicity of the first cover and want to keep that as much as possible.

It's like with my reworking of the cover for How to Rape a Straight Guy into Curt -- I never would have thought having a tightly muscled man wearing a pair of trousers and looking back over his shoulder would so neatly encapsulate the story...but it does.

I may be trying to be too literal as to what the cover must be. I thought of slightly copying this promotional poster for Beautiful Thing, but with a young man in full figure looking at the skyline of Houston, ca. 1975. The vast majority of Houston's skyscrapers were put up after 1980. The image of downtown that they used in this image is from about 1981, at the earliest.

I may be trying to be too literal as to what the cover must be. I thought of slightly copying this promotional poster for Beautiful Thing, but with a young man in full figure looking at the skyline of Houston, ca. 1975. The vast majority of Houston's skyscrapers were put up after 1980. The image of downtown that they used in this image is from about 1981, at the earliest.Which doesn't do much for my using that as part of the cover.

April 19, 2024

Run-around day...

I worked up a potential cover for the cover of NWFO. I like it but it's not getting great response. I've thought up a couple more, using the passport, Houston's skyline in 1975 and an image of Brendan standing and either looking out or looking back at the city. I'll think about it some more.

I worked up a potential cover for the cover of NWFO. I like it but it's not getting great response. I've thought up a couple more, using the passport, Houston's skyline in 1975 and an image of Brendan standing and either looking out or looking back at the city. I'll think about it some more.Ran out to the Apple store and showed the tech how my caps lock came out and I can't get it to go back. Seems a couple of pieces broke in the connector, so there was no way I could have repaired it. He took it in the back for about ten minutes and bam...it was done. Works as good as new.

Also got my test copy of Curt, today, and it looks really good. Crisp printing, good colors on the cover. I didn't really expect any issues, but you never know. I once got a proof copy that was trimmed at an angle and had to resubmit my documents to get it corrected. Wasn't my fault, fortunately.

I'm backing away from social media. The fuckhead MAGAts are out in force praising their orange god and trying to fuck up the legal proceedings against him. One even set himself on fire, that's how insane it's becoming. I've always had issues handling extremists like this, people with no connection to reality demanding the world conform to their insane viewpoint.

Xitter is a cesspool of their shit. In just an hour on there, I blocked 15 nutcases blaming everything the world that's ever gone wrong on Democrats and liberals and queers and abortion and lack of god in schools and on and on. The one bright spot is, Congress might finally get off its collective ass and send Ukraine some help instead of use it to score political points.

Fuck the world, I want to get off.

April 18, 2024

Focused and finished...

Okay, the red pen edit is done on NWFO. I'll start inputting everything Saturday. Give myself a breather from it. There are enough structural changes for it to definitely be draft #9, and I may do another read-through once it's input to make sure it's all in order before sending it out for proofing and commentary.

I'm getting to be a bit leery about a moment I have in the story. Brendan is kidnapped and taken to an isolated area where he is brutally beaten, over dating a Cajun girl. Years later, when he learns his mother has cancer, he's too restless to settle down for the night so retraces that night's journey. And winds up finding the place he was attacked.

The part I'm unsure about is, he'd lost the key to his Montesa bike when the beating took place...and he finds it, when he comes back. That worries me as being just too easy. Too simple and obvious. I've set it up like the fates are leading him back there specifically for that purpose...but it's still a bit much. I may cut him finding that...or rework it. I dunno.

The part I'm unsure about is, he'd lost the key to his Montesa bike when the beating took place...and he finds it, when he comes back. That worries me as being just too easy. Too simple and obvious. I've set it up like the fates are leading him back there specifically for that purpose...but it's still a bit much. I may cut him finding that...or rework it. I dunno.It's just, that little Montesa Impala is like another character in the story. It takes Brendan all over the city. Gives him a quiet sort of cool, overall, and sticks by him. It even leads him to a place where he can find a car that needs lots of work and brings him back to an even keel after all hell breaks loose in his head. So it sort of makes sense. I guess.

Overall, the book is coming together. And it's quietly setting up things that will happen in book 3, Home Not Home. Ah, something to look forward to.

April 17, 2024

Time wasted...

A potential job came through in Philadelphia, overseeing the collection and palletizing a group of storage file boxes for a client. I spent two hours on it...and submitted my part of the estimate. And I can pretty much tell it's not going to happen. Just me, alone, is going to cost nearly $2000, thanks to explosive air fares and hotel rates. Even driving down would be pricy...and take a full day. It's over 400 miles.

I also had to set up a trip to San Francisco and Newport, RI. Which took a couple more hours. Then I made a cottage pie for dinner, with a green bean casserole, and did some grocery shopping...and crashed into a low-blood-sugar phase. When that happens, it takes a while to claw back out and I'm wrecked. I wind up having to take a nap. And I usually come out of it very depressed.

So no work done on NWFO, today. I'm in a bad place, emotionally, and would not do right by the story. I'll work on it, tomorrow.

But damn, that cottage pie turned out good. It's what I ate to get me out of my physical situation. I might have done better with a candy bar or regular DP, but it's what was available...short of eating a spoonful of sugar.

April 16, 2024

75%

Closing in on the newest draft. Number 9. Brendan is about to vanish from his aunt's house to let himself mend from a catastrophic situation. It seems every time he thinks his world is back on track, something happens to derail him...and this time it was brutal.

Closing in on the newest draft. Number 9. Brendan is about to vanish from his aunt's house to let himself mend from a catastrophic situation. It seems every time he thinks his world is back on track, something happens to derail him...and this time it was brutal.I was getting worried that the chapters leading up to this were bland and simplistic, but now see them as the calm before the storm. I guess I'll find out if that's the way of it or not. As a writer, I can never really evaluate my work. Sometimes I read it and I'm so fucking proud of me, I'm like a lion in the middle of his pride. Other times, I wonder if I'm just a superficial slug smearing himself across a semi-wet pavement and thinking it means something.

When I do the inputting of my corrections, this time, I'm going to do it on the PC. Word winds up looking completely different on that as opposed to what appears on my Mac. Same for Excel and emails and everything. Same programs, just not the same. Make it make sense.

When I get done with this draft, I'm taking my Mac in to the Apple Store to have the caps lock key reset. I hope. I'd hate to have to send it back to Mac for repair and not have access to it for a period of time. I've got Ps on here and my images to use for the cover of NWFO. It's under warrantee, so shouldn't cost me anything; it's the time I'm worried about. What's funny is, I rarely used the caps lock. Maybe I need to, more.

Still, I really do like this laptop a lot more than the previous one. It's got its quirks, but they all do.