Ian Colford's Blog

March 10, 2025

Best Reads of 2024

In 2024, between working on a new fiction manuscript and writing reviews, reading remained a favourite activity. I find a “mixed bag” approach to selecting books to read keeps things interesting. I’m a bit of a magpie when it comes to the selection process, choosing new and older titles, books by familiar authors along with authors new to me, many Canadian but also books from the UK and the US, as well as a healthy number of books from other places translated into English. Sometimes the selection is based on a review. Other times I choose a book randomly, because it’s there, or because the cover is interesting.

I recently discovered two publishers offering a fascinating selection of titles from around the globe. Peirene Press is an independent publisher based in the UK, “publishing books from 25 countries and 20 different languages.” Archipelago Books is located in New York and describes themselves as “a nonprofit press committed to publishing exceptional translations of classic and contemporary world literature.” Readers with an interest in expanding their horizons might want to check out the titles on offer from these innovative and adventurous presses.

I continue to find reviewing books a rewarding and challenging way to keep my mind active as I enter year eight of my retirement. The titles listed below (in no particular order) are a few of the highlights from among the 50+ books I read in 2024.

Kudos as well to the graphic designers responsible for all six of these attractive and arresting covers!

Ⴔ

The Harvesters, Jasmina Odor’s luminous debut novel, depicts Mira and her nephew Bernard’s brief visit to Paris through Mira’s inquiring, meditative perspective. Mira and Bernard are both suffering the effects of recent losses. In her forties, childless and recently divorced from David, Mira’s past is very much on her mind. The purpose of the journey is to visit Mira’s mother—Bernard’s grandmother—in Croatia, which Mira fled during the war, eventually settling in Canada. Mira’s father has died, and her mother recently suffered a stroke, so Mira’s level of concern is elevated. The 3-night Paris stopover was Bernard’s idea, a chance for him to revisit the site of a trip he took the previous year with girlfriend Aisha while he broods over their subsequent breakup and his role in what happened. But Mira also has a hidden motive: visiting Paris gives her a chance to perhaps reconnect with Mirko, a boyfriend from the years prior to her marriage, with whom she lost contact but has now tracked down via the internet. Mira has a high opinion of her nephew and regards him as a gentle and painfully self-aware young man whose heart is easily broken. Indeed, their initial foray into the Paris streets hits a detour when they come across an injured pigeon, which Bernard insists they must bring to the hotel and nurse back to health. To Mira, Bernard seems to be at a loose end, undecided about his future and still wistfully in love with Aisha (constantly checking his phone to see if his ex is responding to his texts). But Mira is also perplexed by Bernard’s behaviour, when he seeks an intimate connection with every young woman he meets, including a hotel maid and Alice, the daughter of an American family staying at the same hotel. For her own part, Mira seems stuck in the hollow space between her new and old lives, puzzling over a divorce she’s not sure she even wanted, wondering where David is and what he’s doing, and distracted by concerns regarding her mother’s health and welfare. With limpid, arresting prose, Jasmina Odor captures the restlessness of two characters nostalgic for a safe, settled past, wanting more but wary of moving forward into a future that holds so many unknowns. Like her previous book, the brilliant story collection You Can’t Stay Here (2017), this is a sophisticated, moving and psychologically probing work brimming with insightful observations on loss, transition, and the thorny—sometimes baffling—intricacies of the human heart. With The Harvesters, her first novel, Jasmina Odor proves herself to be a writer of the first order whose fiction is worth seeking out and is sure to reward repeated readings.

Ⴔ

Love, Hanne Ørstavik’s acclaimed novella (originally published as Kjurlighet in 1997), tells a haunting and ultimately tragic story of a young mother, Vibeke, and her son, Jon, who have recently moved from a city to a much smaller town in northern Norway. It is late in the day, late in the year and very cold. Jon is anticipating tomorrow, his 9th birthday, and the celebration he is sure his mother is planning. After supper Jon leaves to sell raffle tickets for his school sports club. He wants to be out for a while, to give his mother time to bake the cake and wrap his presents. But the old man at the first house he approaches buys all the tickets. So, Jon returns home, but quickly leaves again, for the same reason as before. In the meantime, Vibeke has taken a shower. She’s pleased with how her new job is going and thinks she deserves a treat, which for her is a trip to the library to return the books she’s read and to borrow new ones. Vibeke lives in her head, reading non-stop, fantasizing romantic encounters. She’s also fixated on her appearance and preoccupied with making a good impression on her new work colleagues. Jon is not her priority. She’s forgotten his birthday, and through inattention and distraction has not seen her son leave the house the second time. When she calls out for him and he doesn’t answer, she thinks, “Most likely he’s doing something in his room.” Vibeke prepares herself, goes out, gets in the car and drives off. The remainder of Ørstavik’s novella is concerned with Jon and Vibeke’s various encounters, which have a random quality about them but movingly demonstrate the emotional distance that exists between mother and son—one self-obsessed and looking for love, the other distracted by expectations and the newness of everything around him—and the vastly different manner in which they approach and perceive the world. Ørstavik’s third-person omniscient narrative flits back and forth between Jon and Vibeke, sometimes from one paragraph to the next, in a way that might be jarring but acts as a constant reminder of the separate worlds that mother and son occupy and, as the evening progresses, the diminishing odds of them reconnecting. Ørstavik’s prose, expertly rendered into English by Martin Aitkin, gleams like the frozen landscape it so capably evokes. Love is an odd and disturbing little book that places a clear-eyed focus on how each of us is confined to a discrete universe of awareness and emotion that sets us apart from everyone else. Writing powerfully and without sentiment, Hanne Ørstavik shows that she is well acquainted with the lonely passion of the human heart.

Ⴔ

Breakdown, Cathy Sweeney’s searing debut novel, is a sharply observed comic drama of a woman who realizes she’s been playing a role for which she is no longer suited. On a November morning—a morning just like countless others— Sweeney’s unnamed narrator wakes up in her suburban Dublin home, prepares herself for work and leaves the house. But when she reaches the intersection exiting the estate, instead of making her customary right turn toward the city, she turns left, and her adventure begins. It’s an impulsive act, which, at any moment, could be reversed. The woman, in her mid-fifties, has no plan. She does not devote a great deal of thought to what she’s doing or where she’s going. At this early point in the story, her observations are largely mundane: “The sky is full of November white, more absence than colour.” But as her journey into the unknown continues, we learn more about the life she’s escaping and what may have pushed her over the edge. It is a comfortable life, ordinary and safe; a life filled with joy and love, but also disappointment, compromise and numbing routine. And as her self-scrutiny deepens and further vistas are revealed, she comes to recognize that no single event has sparked her decision to leave it all behind. The process that’s culminated in her absconding has been ongoing for years. She is also far from ignorant of the fact that her decision will alter not just her own life, but other lives. As the hours pass—as she ignores a stream of phone and text messages from her husband and children—she comes face-to-face with the repercussions of her actions. With each mile traveled, it becomes more difficult for her to turn back. Sweeney constructs her novel along two compelling narrative threads. In the first, we follow the narrator’s journey from her Dublin home to a remote cottage in rural Wales, a trip taken via car, bus, train and ferry. This, it turns out, is flashback. The other thread is the present day, when she’s been settled in the cottage for about a year, tending her garden, making new friends and living a simple, solitary, admittedly selfish, but apparently gratifying life. Sweeney’s staccato rhythms and clipped sentences capture perfectly the progression of emotional states that her narrator experiences as her circumstances evolve, turning this into an unsettling and often breathtaking work of fiction with the forward propulsion of a whodunit. At times the suspense is agonizing, as the narrator crosses another unfamiliar threshold or places her trust in a stranger. But though Breakdown’s entertainment value is undeniable, it is Cathy Sweeney’s subtly devastating commentary on the modern world we’ve constructed for ourselves that truly resonates.

Ⴔ

For her entire life, Hannah Belenko has been trying to escape the toxic legacy of her childhood. Raised in suburban Ontario by a controlling brute of a father who ruled the household with an iron fist, a mother who learned the hard way that survival depends on keeping her mouth shut, and an older brother who’s following in his father’s footsteps, Hannah has been indoctrinated into a “family code” of silence. When we meet Hannah in 2018, she’s 20-something, living in Ontario with her 6-year-old son Axel, and facing questions from authorities about her lifestyle. Hannah’s troubles are not new. She already lost her daughter Faye to the foster system and her parenting is being monitored by Ontario’s child advocacy service. After a violent confrontation with her abusive boyfriend, she flees to Halifax, where she hopes to re-connect with Bashir, Axel and Faye’s biological father, and squeeze him for the child-support he owes her. Hannah’s goal has always been a better life for her children, but everything she does backfires. There’s never enough money and she can only find relief from the constant struggle to get by with booze and drugs. In the novel’s initial chapters, the reader can see that it is Hannah’s angry, selfish, and impulsive behaviour that presents the most serious impediment to achieving the better life she’s seeking. Abrasive and combative, perpetually in survival mode, she blames others for her problems. She is distrustful of authority and suspicious of anyone who offers a helping hand. The Family Code, Wayne Ng’s gripping second novel, chronicles a pivotal year and a half in Hannah’s life as she struggles to cast off the lingering effects of a traumatic childhood and for the first time find the courage to confront her demons. Hannah and Axel narrate in alternating chapters, often providing conflicting accounts of the same events. Hannah Belenko is not an easy character to like. She is quick to anger and often takes her frustrations out on her son. She is dishonest with herself and others and can’t resist the temptation of a quick buck. But as the harrowing story of her childhood is gradually revealed, we begin to understand how she became the way she is. After a series of missteps, ill-fated detours and poor choices, she finally realizes that she won’t save herself and Axel until she stops running from the past that haunts her, and by the end of the book she’s more than won our sympathy. Wayne Ng’s novel is not an easy read, filled as it is with graphic depictions of violence, cruelty, and the casual mayhem of physical and psychological abuse. But it is here, in its unvarnished honesty, where its power resides.

Ⴔ

In Sara Mesa’s engrossing and deliciously enigmatic novel Un Amor, Nat has left her life in the city and rented a house in rural La Escapa. Here, in a tiny village many miles from the nearest large town, she embarks upon a translation project. But there are many things weighing on Nat’s mind. She left her previous job under a cloud and has not yet reached an understanding of how she could have allowed an episode of reckless poor judgment derail her life and career. Nat is unattached, a woman alone, and it’s not long before she begins to see that this circumstance adds another to the list of challenges she is facing. Soon after moving in, for companionship, she adopts a dog, which she names Sieso. Disappointingly, the animal is nervous, unpredictable and distant. But she decides to keep him, despite Sieso not being well suited for the purpose she’d intended. For Nat, life in La Escapa does not proceed smoothly. Her landlord, a creepy misogynist with an ax to grind, dismisses her complaints about the leaky roof and tells her she can fix the leaks herself or catch the drips in pots and pans. He doesn’t care. But the landlord’s negligence proves fateful. One of Nat’s neighbours, Andreas, a handyman of sorts, known locally as “The German,” sees what she’s putting up with and offers to fix the roof if Nat, in turn, provides a service for him. Mesa maintains heightened tension throughout the book, which is narrated in the third person from Nat’s guarded perspective. Her interactions with her neighbours are, without exception and for a variety of reasons, fraught, and the uncurrent of menace that pervades the story results from Nat’s sceptical nature, tragic lack of confidence, and tendency to question everyone’s motives, including her own. We spend the entirety of Un Amor observing La Escapa and its residents from Nat’s point of view, and it is not a happy place to be. Nat takes nothing at face value. Her mind is always dissecting, always seeking answers. She is painfully aware of her outsider status. It makes her uncomfortable, being on the outside looking in. And yet at virtually every turn her actions raise hackles and guarantee that she will never be accepted into the community. For a while the amor of the book’s title provides Nat with a refuge, a physical distraction away from her churning thoughts. But in the end, it turns corrosive and causes disappointment and heartache. The rural world that Mesa conjures is placid on the surface, but her masterstroke is gradually revealing it to be a mysterious and unwelcoming place seething with distrust, resentment and hostility. In Un Amor Sara Mesa fearlessly plumbs the depths of human passion and depravity. Disturbing and filled with contradiction, Un Amor is never an easy novel. But it is also never less than fascinating.

Ⴔ

There is a breathless quality to Keith Hazzard’s collection of 60 tersely written fictions, aptly titled Brief Lives. As the title suggests, these are lives summed up, sometimes in a single paragraph, but complete with incident, romance, ironic twists of fate and blunt statement of fact: a roller-coaster with each denouement followed headlong by the next. Hazzard takes his inspiration from quotidian experience. His characters are the husbands, wives, sons, daughters, luckless young men, divorcees, accident victims, criminals and adulterers among us. Many of the pieces proceed by implication, the driving force being what’s left unsaid, hovering between the lines. “Love and Strife” describes a love triangle at a hat factory: Dennis lives with Laureen but falls in love with Shirley. Difficulties ensue, firings, estrangements. But the story turns on a single line: “Time swung its axe.” And afterward, everyone gets what’s coming to them. In “All Hallows,” it’s Halloween and Bruce Rutledge is savoring middle age as life’s pressures ease up. Then he gets a call “on the burner phone,” and cooly fetches a body for disposal, but won’t let the job weigh on his mind because he has “candy to pick up and a pumpkin to carve.” Other pieces strike a more contemplative, even nostalgic tone. “Satellite,” the enigmatic tale of the final months of Phyllis and Lowell Steinbach’s marriage, ends with Lowell “living on the other side of the world, planning a trip to the moon.” There is violence here as well, implied, dreamed and committed, leaving in its wake grievous bodily harm, trashed living rooms, or even a basement full of chopped-up mannequins. The variety of narrative styles is remarkable, and some of the pieces—the mysterious “Vječan” is an example—generate enormous tension in just a few lines of clipped prose. Throughout, Hazzard keeps his cards close to his chest, and the reader is occasionally left wondering what’s happening. But, because of their brevity, the pieces invite subsequent readings, which might offer an altered perspective or a new angle of interpretation. And everywhere the jolt of poetry leaps from the page. In “Kairos,” Lee “had no wishes larger than the day he was in.” And in “All the Lovely Judies,” Jon Tropp and his dog are out tramping “through the cold slap rain and grasping mud.” The urgency in the telling is palpable. It’s almost as if the author was watching the clock tick down and had no choice but to get these stories told before it was too late. The pithy, rapid-fire delivery gives the reader little chance to absorb what they’ve read the first time around, but that simply makes re-reading the book an essential delight. Keith Hazzard writes like a man on fire, and Brief Lives is a virtuoso performance, as entertaining as it is elusive.

February 29, 2024

Best Reads of 2023

Last year I spent a lot of time editing. This is because I was having not one, but two books published.

Editors are demanding and have every right to be, and it’s the author’s job to take their recommendations to heart. We accept on faith that an editor hired by the publisher to whip a manuscript into shape for publication knows their stuff. Which probably includes a thing or two about how many words are actually needed to say something. The author, on the other hand, has agonized over every word and might not take kindly to having some of them, or (more frequently the case) a lot of them, ripped out. A crucial but in the process is that the editor is coming to the manuscript with a fresh and objective outlook and can see things the author is blind to: such as redundancies, overlong constructions and witty turns of phrase that sound good read aloud but serve little purpose and only slow down the narrative.

Two manuscripts passed through the editing process in 2023, but only one got published. I worked on the edits for The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard through spring and early summer. The book was published on November 1, though copies were made available much earlier. Witness was supposed to be published in the spring, but delays pushed it to the fall. I worked on the edits from mid-summer into September. Then an illness at the publishing house, The Porcupine’s Quill, put a halt to the process. After a few weeks there was no clear timeline for moving the project forward and the folks at PQ decided reluctantly to cancel publication. I have now begun the process of searching for another publisher for that manuscript. However, I remain grateful to everyone at PQ for having faith in my writing and wish them nothing but good fortune.

Despite these and other activities, I did a lot of reading in 2023 and the books noted below provided a better than average distraction from the stimulating and sometimes arduous task of revisiting and rethinking my own prose.

Ⴔ

In The Gull Workshop, his second collection of short fiction, Harry Mathews offers up thirteen fiendishly inventive stories brimming with irreverence and comic energy. Mathews generally sets these tales of modern angst in a here-and-now that closely resembles the world as we know it, but often with a playful twist of weirdness that can catch the reader off guard or leave his characters scratching their head. A prime example is the title story, in which a small group of older men from the community have signed up for a “Gull Workshop,” even though they don’t know what it entails and are none the wiser after a lengthy discussion with their enigmatic facilitator on precisely that question. In “The Death of Arthur Rimbaud,” the renown French poet has without explanation turned up in a small community in rural Canada, where he’s renting a house and living on his own. The narrator reports this in breezy, matter-of-fact terms, even though some of the details, as he readily admits—such as Rimbaud’s birth date of 1854 making him over 150 years old—are “hard to swallow.” Other stories tackle obsessive behaviours. In “Brick,” Vince and Isabel (“Canadian snowbirds”) regularly winter in Florida, and all is going well until one morning Vince discovers a patio brick out of alignment at the edge of the property, repositioned in a way that can only mean one thing: human intervention. Over subsequent days and weeks, as the same brick is repeatedly tampered with, Vince engages in a battle of wills with his unseen tormentor. But Mathews is wily, and just when we think we’re reading a story about a man spiralling into madness over a triviality, he broadens the scope of the narrative to plausibly include a shooting at the airport in Fort Lauderdale and Vince’s Christian beliefs. Other stories take a sardonic perspective on family tensions (“Brother,” “Garabandal”) and knotty male-female relationships (“The Apocalypse Theme Park,” “What My Wife Says”). The collection ends with three delightfully ironic linked stories that skewer academia, among other things, in which our hapless hero, Hanrahan, confronts his intellectual limitations and lack of ambition while searching for a career and something that resembles meaning amidst life’s random chaos. Anyone who’s tried it knows that comic writing is much more difficult than writing for dramatic effect. Mathews carries it off with grace and confidence, seemingly without effort, again and again. And yet, he never seems to be showing off. The Gull Workshop—wise, insightful, wryly observant regarding humanity’s copious foibles and infinite capacity for misunderstanding—is classic Harry Mathews.

The characters in Anne Baldo’s captivating debut story collection, Morse Code for Romantics, are searching for connection, hoping for love, or even just a little human warmth, amidst the lonely tedium of aimless days and anxious nights. Many of Baldo’s characters are young and aware of a world of promise and opportunity that awaits them, but are unsure how to reach that world and attain that promise, or else they’re indifferent to its existence. Baldo sets her stories in a distinctly unpromising landscape: a desolate and backward version of small-town southern Ontario, a place scarred by neglect where rust and rot spread unhindered, where gardens are left to become tangled and chaotic. “We lived on a dead-end street,” Ophelia observes in “The Way to the Stars,” a statement that succinctly sums up the lives of many of the people we meet in these stories. Ophelia loves Tamás, but Tamás loves Molly. He has time for Ophelia too, but only after a bust-up with Molly, who, he knows, will always come back to him. “I existed for him in the voids between,” Ophelia reflects despairingly, “and what exists in voids is nothing.” The title story takes place at a wedding. Trevor and Livvy are tying the knot and Jordan, who narrates, slowly reveals why the mood is anything but celebratory: this is not a happy event but instead a forced union between two very young people who made a life-altering mistake. Baldo’s stories generate a strong sense of time passing, of opportunity slipping away, and are often steeped in melancholy. Lucy, in “Last Summer,” spends her break from university with friends Sadie and Rhea and boyfriend Arthur, binge drinking, drifting from party to party, from one encounter to the next, obsessed with cheap jewelry, lip gloss, nail polish and Everett, with whom she’s infatuated. Lucy's is a life of inconsequential distraction, but Anne Baldo’s prose digs beneath the veneer to reveal unexpected complexity in her characters’ yearnings and regrets. Baldo’s families are invariably broken, often beyond repair. Young Colt, in “Fish Dust,” is terrified of—and fascinated by—his estranged father and rough half-brothers. Jumping at a chance to go fishing with them, the experience teaches him what his mother already knows, that his father is a man who leaves only destruction and sorrow in his wake. And in “Wishers,” Demetria is searching for her lost daughter. Cora, a university student, has fallen under the sway of an older man, Hayes, a black-sheep son of privilege, and an addict. When she finally tracks the pair down at a fleabag motel, she is unable to persuade Cora to leave Hayes and so finds a way to make generosity her revenge. Throughout Morse Code for Romantics, Baldo’s prose shines. Her writing effectively evokes a world that is familiar and strange at the same time, pulling the reader into lives scarred by loss and loneliness. These are poignant, wise, memorable stories by a writer whose vision may be bleak, but it’s a vision that rings true on every page.

Rune Christiansen’s prize-winning novel (capably translated from the Norwegian by Kari Dickson) is a paean to solitude which suggests that, while loneliness might be widely regarded as an unfortunate aspect of the human condition, it can also be a choice, one that does not have to be sad or tragic. Lydia Erneman grows up in Northern Sweden, an only child living in intimate proximity to the natural world. Her parents provide for her physical and emotional needs, but even as a child she senses that their marriage is “a form of coexistence” sustained and strengthened by “distance,” “detachment” and “absence.” Lydia matures into a dual awareness, of her connectedness to all things and the separateness that enables her to objectively observe what goes on around her. Above all else, her childhood teaches her how to be alone. After graduation she becomes a veterinarian and takes a position in rural Norway. At this point her life becomes busy and purposeful. The hands-on nature of her veterinary practice suits her. The work is fulfilling and seems to satisfy her professionally and emotionally. Believing she is content in her solitude, she neither craves nor seeks human contact beyond professional colleagues and the farmers whose animals she treats. But Christiansen’s quietly powerful narrative demonstrates how events can propel us in unexpected directions, subverting our intentions and landing us in the midst of friendships and attachments we never saw coming. Subtly, inevitably, Christiansen draws us into Lydia’s apparently uneventful life in the manner of a film that ticks along scene by scene, building tension on the sly, as if behind the viewer’s back, until before we know it, we can’t pull our eyes away from the screen. Lydia’s emotional growth occurs while we’re distracted by Christiansen’s contemplative, melancholic prose, which evokes a Nordic landscape of fading light and muted passions. Lydia Erneman’s thoroughly unremarkable days encompass achievement and disappointment, love and loss, serenity and frustration, confusion and certainty. The events that occur in these pages rarely rise above the commonplace. But as we read, Lydia’s story gradually becomes riveting, and we emerge from it with a sense that life lived unobtrusively and on a small scale can be meaningful, impactful, joyous and profoundly worthwhile. The Loneliness in Lydia Erneman’s Life is a triumph of bare-bones, understated storytelling that celebrates the rhythms of ordinary life, those precious moments we spend recalling a childhood memory, listening to the wind in the trees, or sharing a cup of tea with a friend. This is a novel that transcends the quotidian lives depicted in its pages. Haunting, captivating, uplifting.

Tove Ditlevsen’s bleak, emotionally disturbing stories zero in on moments of excruciating tension and vulnerability in the lives of ordinary people. The preponderance of Ditlevsen’s subject matter derives from the push-pull of domestic relationships, the power struggle of the male-female dynamic after long periods of co-habitation, or the breakdown of a connection that one presumes was at one time affectionate. In “The Umbrella,” Helga’s husband, resentful of her delight over acquiring a new umbrella, destroys the instrument as she looks on, an act that, in the bitter aftermath, Helga calmly accepts as she reflects that “everything was the way it was supposed to be.” “The Cat” relates a fraught tale of a couple who come into conflict when a stray cat joins the household, upsetting the domestic power balance and giving the wife the upper hand. “A Fine Business” describes a pregnant couple’s viewing of a house they want to buy, and the young mother-to-be’s guilt and sadness when her husband joins forces with the real estate agent to negotiate the price down, exploiting the female seller’s desperate need. In “Two Women” Britta, suffering from a case of frayed nerves brought on by her overbearing husband’s criticisms, seeks to restore her equilibrium at the beauty parlour. But when she sees the young hairdresser is upset, and then pries an admission from the girl that her husband has left her, Britta is not sympathetic but instead resentful that she must now share someone else’s burden of misery. In most of these stories it is the female partner who must cope with a moody, domineering husband. But in “The Trouble with Happiness,” it is the wife/mother’s judgmental presence that sets a tone of powerful negativity in the domestic setting, cancelling out all lightness and joy. Her husband copes by retreating, becoming a passive nonentity in his own home, and the daughter, who narrates, is counting down the days until her eighteenth birthday, when she will be free to live wherever and with whomever she wants. Conflict in Ditlevsen’s fiction sometimes arises suddenly and can be unexpected and unintentional. A mistimed smile or sidelong glance, or a casual remark, seems hurtful to the person on the receiving end, who then begins to see the other person differently. But more often than not she writes of people who have grown weary of each other and situations where love has withered and the relationship endures more because of inertia than anything else. Not for all tastes, but Tove Ditlevsen’s stories and novels, reminiscent of the work of British author Anna Kavan, deserve a place in any discussion of psychological realism in 20th-century European literature.

In Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You, her masterful second collection of short fiction published in 1974 (Lives of Girls and Women is widely considered a novel), Alice Munro’s art takes a significant step forward. Though the subject matter remains much the same as in her first two books (stories of quotidian lives mainly told from female perspectives), in these stories she is extending her reach and experimenting with voice and form, light and dark. Many of the stories are built around memory and are often filled with expressions of disappointment, grief, regret, sometimes bewilderment, occasionally satisfaction with how things have turned out. In the breathtaking title story, Et is recalling her beautiful, impulsive, temperamental older sister Char. The sisters grow up, a tight-knit pair, in small-town Ontario, Char much more dramatic and worldly than her sister, and the more adventurous when it comes to love. Char’s early beau is Blaikie, whose family owns the local hotel and spends the off-season in California. When Blaikie marries someone else, Char takes poison. It’s Et who saves her. Later Char marries Arthur—a teacher, an unexceptional man—and lives an ordinary life. But the poison episode remains with Et, who one day makes a startling discovery in Char’s kitchen, which leaves her forever wondering what her sister might have been capable of. “How I Met My Husband” is narrated by Edie, who is recalling when she was fifteen and working as housekeeper for the Peebles, Dr. and Mrs., and their two small children. Though not farmers, the Peebles live in farming country, five miles outside of town. One day a small plane lands in the empty field across the road from the Peebles’ house. It turns out the pilot, Chris Watters, is touring his plane from town to town, and for a small fee will take people up to enjoy the view. By happenstance, Edie strikes up a casual friendship with Chris, which quickly becomes physical, and soon Edie’s head is filled with all kinds of romantic notions. When Chris moves on, leaving behind Edie’s broken heart and an empty promise to write to her, Edie’s life takes a turn she never saw coming. And “Executioners” is narrated by Helena, whose father is a drunk and whose inattentive mother nurses her grudges lovingly. Helena is tormented by her peers, ridiculed because of her odd clothing and her father’s dissipation. But Helena is a curious and generous child who, through an act of kindness, comes to the attention of Howard Troy, the shiftless son of the town bootlegger, Stump Troy. Howard starts bullying her, for no better reason than that “he may have seen the glimmer of a novel, interesting, surprising weakness.” The story turns on the family of Robina, Helena’s mother’s housekeeper, whose younger brothers are enemies of Stump Troy. In the story’s principal scene, Helena and Robina stand among the curious onlookers witnessing the fire that one night consumes the Troy family home. The event is tragic, but Helena views the spectacle coolly, reporting it in clinical terms, hinting but never overtly suggesting who might be responsible. Throughout, Munro’s prose is flawless: precise, understated, rarely drawing attention to itself, but shining nonetheless, evoking character and setting in painterly fashion: “Her tall flat body seemed to loosen, to swing like a door on its hinges, controlled, but dangerous if you got in the way.” In Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You people are often mysterious to each other (and sometimes to themselves), their actions troubling, their motives opaque. Munro’s narrators spend a good deal of time and mental effort wondering how and why they do the things they do. Munro seizes on this aspect of daily life and turns it into a major building block of her fiction. The result is a collection of poignant, thoughtful, loosely structured dramas that eloquently explore what it means to be human. Essential, vintage Alice Munro.

Leo McKay is no stranger to addressing explosive themes in fiction. His prize-winning novel Twenty-Six, published in 2003, is a riveting account of the Westray Mine disaster from the perspective of the family of one of the dead miners as well as a searing indictment of corporate greed. In What Comes Echoing Back, McKay tackles the impact of social media on communities and individual lives. In a narrative that crosses several timelines, McKay’s novel focuses on two teens who have seen their lives turned upside down after their images were posted online without their consent. Patricia’s experience is one we’ve seen lead to tragedy far too often. After reluctantly attending a drinking party with two friends, she wakes up groggy and hungover to learn she’s been drugged and sexually assaulted and that a video of the event is going viral on the internet. To make matters worse, a friend who was also assaulted at the party later commits suicide. Soon Patricia finds herself the unwilling centre of attention in a small rural town in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley where everyone knows everyone else’s business. Unable to cope with the humiliation, reeling from grief, feelings of self-blame and an overwhelming sense of worthlessness, Patricia goes to live with her Uncle Ray in Hubtown, where, seeking anonymity, she changes her name to Sam, keeps her head down and hopes nobody who saw the video recognizes her. Robert (nicknamed Robot), son of an alcoholic mother, is a talented guitarist whose life revolves around music. He’s also physically imposing—a trait he attempts to downplay with a low-key, self-effacing manner—but which attracts attention nonetheless. As the novel begins, Robert has just been released from prison after serving a year for killing another student in a fight. The killing was unintentional. In fact, Robert hardly knew the other boy and had no issue with him. But the fight was encouraged and staged by two students looking to gain notoriety by urging people into violent confrontations and posting the fight videos on their social media channel. Robert and Sam meet in music class and form a bond that grows out of their status as social outcasts. McKay’s novel describes Sam’s and Robert’s halting efforts to re-integrate themselves back into a society they are not sure wants anything to do with them while shielding themselves from further pain. In a series of moving scenes drawn with great compassion, we witness their first tentative steps toward one another, watch them overcome their doubts, and see how their mutual trust grows over time, bolstered and sustained by the healing power of music. At its core, What Comes Echoing Back tells a relatively straightforward tale of two damaged, vulnerable people struggling to build a connection following life-altering trauma. It leaves us wondering not only where their lives will take them next, but also questioning the forces at work in a world that seems to offer no defense against the malicious exploitation of technology that has the power to destroy innocent lives with a keystroke. A note of caution: it’s possible the depictions of violence and alcohol addiction in this novel could be triggering for some readers. Rest assured that Leo McKay’s treatment of this difficult material is unfailingly engaging and honest.

January 8, 2024

The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard: 25-years to the Guernica Prize

I started writing the novel that became The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard in 1994. I had been writing fiction “seriously” for about a decade and had met with some success placing short stories in literary journals. I was working at the Dalhousie University Libraries and was eligible for a half-sabbatical leave. My sabbatical project was an academic paper on “digital writing.” It will seem quaint from our vantage point in the tech-saturated 2020s, but in the early 1990s widespread use of computers for writing and communication was in its infancy, and I was keen to explore the effects of the new digital tools on the act of writing.

I also had an idea for a novel and thought I could make use of the time when I wasn’t working on my official project to get started on that.

Admittedly, I was more committed to creative than academic writing. Before my sabbatical started I convinced the chair of the English Department to let me move into a vacant office. I told him that, if he had no objection, I could meet with students to discuss their own creative writing efforts. Word went out that I would be in the department for the first six months of 1994 and was available to discuss creative writing with students who found the topic of interest. I would be an informal “writer in residence.”

For the next six months, with my time and energies divided, I managed to write the first 50 pages of the novel, along with 100 pages of a text that was eventually published as a stand-alone monograph by the university.

Ⴔ

Joseph had come to me fully formed: a fastidious man in his late thirties, bored with his life, who falls in love with his much younger cousin. Fiction writers know what it’s like when an imaginary character intrudes into your daily routine. Everything you do and say is coloured by a foreign perspective. Your thoughts are not entirely your own. Your observations are no longer simply things that pass before your eyes, they are potential fodder for the story you’re writing. As you work, the story becomes an obsession, and if you’re not careful it can push real life into the background. Regardless how you deal with it, you cannot help but become slightly unhinged because you’re trying to live normally under abnormal conditions.

Of course, none of this matters if the work is going well.

Ⴔ

The sabbatical ended and over the next four years, while I was busy doing other things (working full time, editing a literary journal, helping to organize a reading series), I completed a first draft of the novel, which I called “Sophie’s Blood.” I read it over and was happy with it. And I was encouraged because I had workshopped portions of the manuscript at the Maritime Writers’ Workshop and received positive feedback.

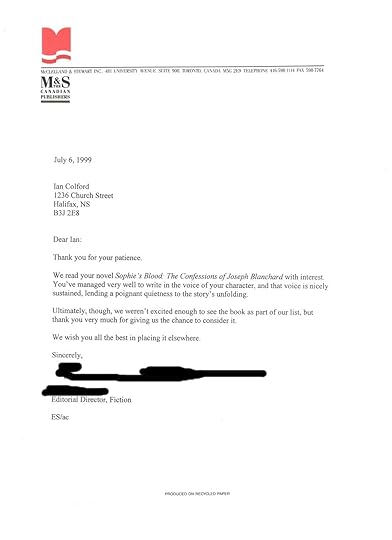

The next step was to explore publication opportunities. It seems hard to believe now, but in 1998 large commercial publishers would take submissions straight from authors, even obscure authors like me with a sparse track record and virtually no public profile. Since there was nothing to stop me setting my sights on the biggies—Knopf, Random House, Harper Collins, M&S—I started with them.

In those days submitting a manuscript to a publisher meant printing a copy and sending it by parcel post, not an inexpensive proposition even 25 years ago. Over the next couple of years, I burned through more than a few boxes of printer paper, probably a dozen toner cartridges and hundreds of dollars in postage before deciding to take a step back to re-examine my options.

Ask anyone about the submission process and they’ll tell you many things, but they’ll tell you this for sure: it’s slow, frustrating, and the only certainty is rejection. I’ve written about this previously. Some publishers respond promptly. Others take their time. Some don’t reply at all. The level of detail in these responses varies greatly. The responses I received ranged from bluntly dismissive to gushingly complimentary. A couple of publishers apparently gave my submission serious consideration, admitting that it had come close to being accepted. One wrote back after more than a year apologizing for keeping the manuscript for such a long time, but “everyone in the office wanted to read it.”

By early 2001, however, nearly three years after finishing it, Sophie’s Blood remained unpublished. Clearly, I was doing something wrong.

Ⴔ

I reread the manuscript, which I hadn’t done in some time. Typos leapt out from almost every page. Everywhere I found clumsy syntax and passages flaunting their redundancy, begging to be cut. It was flabby and self-indulgent. I had sent the manuscript out too soon. It needed a workover. I contacted a writer friend and asked him to read it with an eye to tightening the narrative. Two or three months later I received Richard’s comments. His suggestions, if I followed through on them, would shorten the manuscript by a quarter, or about 100 pages.

I made the changes.

Now I was facing a new set of questions, the first of which was Is this manuscript really any good? It had been rejected at least 20 times. Richard had said it was okay but needed work. Well, I’d done the work.

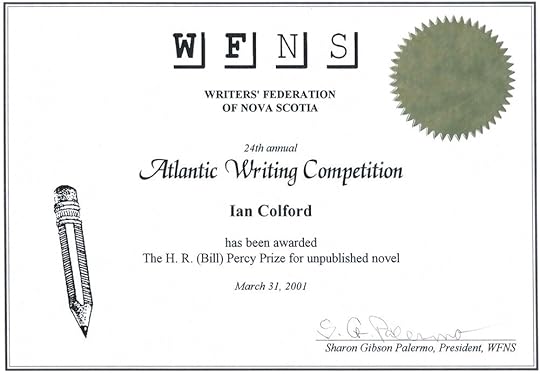

I’m a member of the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia. I’ve served on their board, helped judge their contests. The Fed runs an annual competition for unpublished manuscripts. These days it’s known as Nova Writes. In 2001 it was called The Atlantic Writing Competition. I decided to enter Sophie’s Blood in the competition to see what would happen. One of the perks of paying the entry fee was that contestants received written comments from the jury, which was normally made up of people with a strong interest in books and storytelling: writers, librarians, booksellers, etc. I figured at the very least I’d have a few words from seasoned readers to guide my next set of revisions.

Sophie’s Blood won first prize in the novel category.

Maybe I was doing something right after all.

Ⴔ

I continued to submit the manuscript to publishers without success.

In 2003 a literary agent I was corresponding with pointed out that the movie Sophie’s Choice had made a major splash and a novel called Sophie’s World had been a global bestseller. Her point was that to avoid confusion I should either rename my character or find a better title. That’s how my novel became The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard. Years later another agent sent the manuscript to a few publishers and noticed the comments they were making often repeated a similar sentiment, that Sophie’s character was sketchy and lacked definition. She suggested I make some revisions, maybe even write a new scene or two that would help solidify Sophie in the reader’s mind. I made these changes in 2018.

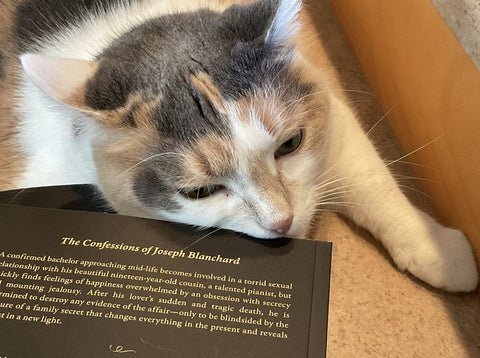

By 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic was in full swing, and we were all staying home. Late in the year I suddenly found myself without an agent. I had an inventory of four unpublished manuscripts, two novels and two collections of short fiction. I reread everything, including the Confessions manuscript. It was the same narrative it had always been, the one in which Joseph Blanchard, writing in 1971, describes his role in a series of devastating, life-changing events. But while reading, I could see that the passage of almost 25 years had altered the reader’s relationship to the action. The historical perspective had shifted. The story was set fifty years in the past: a lifetime ago. It needed something to reset the balance. I hit upon the idea of a letter that would bring the novel into the contemporary moment by signalling to the reader that the story is taken from an old manuscript discovered in the home of a woman who had recently died. This letter is transcribed in the book’s the opening pages.

Ⴔ

Stuck in the house and with the option of making submissions via the internet, I submitted all my manuscripts. When the rejections arrived, I submitted them again. Sometimes I didn’t even wait for the rejections to arrive. Eventually the calendar flipped to 2022 and I decided to enter The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard in the Guernica Prize competition. Here was another chance to put the work in front of readers who would not be constrained by the business side of publishing, whose chief concern was not marketing strategies or sales figures. They would simply read the novel and decide if it passed muster.

To say I was delighted to learn that The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard was selected for the Guernica Prize shortlist, and then named the winner, is an understatement. The news marked the end of a journey that was half-way through its third decade. I had long since lost count of the number of people who had read the manuscript in its various forms. But I am grateful to every one of them, especially those who went to the effort to tell me where I had gone wrong and what I could do about it. Over the years I had plenty of time to imagine what the finished product might look like, and I’m more than pleased with how it’s turned out. David Moratto’s design is outstanding, editor Lindsay Brown has done a superb job, and the whole team at Guernica Editions has been more than supportive.

I could have given up long ago, but in 1998 I believed I had written a novel that people would enjoy reading, and I still believe that. I’m glad now that readers will have a chance to decide for themselves.

Ⴔ

Ⴔ

April 6, 2023

Best Reads of 2022

In 2022, as in years past, I read a mix of new and older titles, a hodgepodge of genres, books written in a variety of styles. Dystopian fantasy, horror, historical, suspense, mystery-detective, literary fiction … All are represented to varying degrees in the 51 titles I read in 2022.

I’m drawn to psychological realism: novels and collections of short fiction that illuminate the human condition in the modern and contemporary world. Most of the fiction I read is character-based, meaning the author is writing about people whose world closely resembles our own and relying less on sudden or outlandish plot twists and more on psychological depth and character development to move the story forward. In this kind of fiction, story and character are on a more or less equal footing because story arises from character. The author knows that both elements must thoroughly engage the reader to keep him turning the pages. And for the most part, the books I read do this. The books included here do this very well indeed.

I’ve harped on this before, but it bears repeating. We write fiction because we’re curious about human behaviour and motivation. We read fiction for diversion, for entertainment, to go places we might never visit and experience life from a perspective that is not our own. But we turn the pages to find out what happens next. The books listed below provide plenty of reasons to keep turning the pages.

Dawn Promislow’s slow burning novel, Wan, takes the reader back to apartheid-era South Africa. It is 1972. Jacqueline, an artist—a painter—is a white woman living a comfortable life in suburban Johannesburg with her husband, Howard, a partner in a law firm dealing primarily in corporate law. Jacqueline and Howard have two children, Helena and Stephen. They employ three black workers to perform the household chores. The family is privileged and prosperous. Jacqueline and Howard are also painfully aware that South Africa’s social structure is based on a grotesque injustice, and despite living under a system that favours them because of their skin colour, their political sympathies are emphatically at odds with the country’s authoritarian ruling party. But other than treating their hired help well, there is little they can do. The penalty for dissent is severe, and with government informants everywhere, speaking out will only make them targets for the police. So, like many white South Africans who opposed apartheid, they resist in silence and keep their moral objections to themselves. Then, early in the novel, they are presented with an opportunity to aid the cause in a real way. Howard’s law partner, who has contacts within the ANC (African National Congress), needs to safeguard an anti-apartheid activist who is wanted by police and asks Jacqueline and Howard to provide the man with temporary sanctuary. Joseph Weiss moves into a small building at the rear of their property that they’d been using to store household odds and ends, and in so doing sets off a chain of events that ultimately renders Jacqueline and Howard’s life in South Africa untenable. Fifty years later, Jacqueline, widowed and living in New York, unburdens herself, narrating an account of those months of Joseph’s tenancy, telling us, “I’m too old to hold on to this story any more. So I’m going to tell it to you.” Wan recounts an exquisitely suspenseful tale of searing guilt, moral ambivalence, misplaced trust, and heart-rending honesty. Promislow relates Jacqueline’s story in crystalline prose, using a contemplative voice tinged with weary resignation that pulls the reader in and doesn’t let go until the final pages. Promislow is patient and thoughtful, and she expects the same of her reader. The story is deliberately paced. Details and events accumulate gradually, ramping up the stakes and building tension to an excruciating level. The book provides a quick, compulsive read, but the rewards of this vividly imagined, elegantly crafted novel are many. With Wan, Dawn Promislow establishes herself as a bracing, shining talent. Readers of this, her second book and first novel, will be eagerly anticipating her next.

The connections that bind people together, that shape destinies and affect lives for good or ill in the contemporary world, is fertile terrain that Alexander MacLeod explores in his second collection of short fiction. These eight elegantly written stories bring searing focus to human relationships tested by unforeseen circumstance. MacLeod’s characters are distant relatives, husbands and wives, mothers and fathers, lovers, neighbours and strangers who have ventured or been drawn into situations that threaten or challenge something they hold dear. David, the narrator of “Lagomorph”—father of three grown children and separated from his wife, Sarah—is living by himself in the family home with Gunther, the pet rabbit. What blew the marriage apart? “I think we just wore down,” he explains in blasé terms, “and eventually, we both decided we’d had enough and it was time to move on.” The separation is amicable. But David, alone and adrift, finds his life profoundly altered. Almost inevitably his days revolve around the aging rabbit, Gunther, who is his anchor to the past and his fragile bridge to the future. David claims that all is well, that he’s adjusting. But when a crisis occurs—one that places Gunther’s life in danger—his fear is existential. In “The Dead Want,” the tragic death of his 20-year-old cousin Beatrice brings Joe’s family back to Nova Scotia for the funeral, where, finding the place and the people different from how he remembers them, he is emboldened to act out the changes he sees in himself. In “The Ninth Concession,” which is set in Ontario farming country, the young narrator’s long-time friendship with Allan, the son of his well-off neighbours, the Klassens, abruptly ends after a disturbing, late-night encounter. “Once Removed” tells the story of Amy and Matt, who are manipulated into visiting Matt’s great aunt. But the old lady’s true motive for issuing the invitation doesn’t become clear until after they arrive at her apartment. And the collection’s final gripping story, “The Closing Date,” told in retrospect a few years after the event, describes the eerie close encounter between a young family and a murderer on the day the couple are set to close the deal on their new house. Throughout, the narrative tone is contemplative and unhurried. MacLeod writes with unfailing ease and confidence; his uncluttered prose sparkles, seducing the reader with natural, plain-spoken rhythms, while the stories themselves enthrall. The seeming effortlessness with which these tales of modern angst are composed is deceptive: a true artist in total control of his craft, MacLeod keeps the nuts and bolts—the sweat and agony--of the creative process well hidden from view. The collection sets its sights on the anxieties that plague everyone living in this fraught modern world, the myriad dilemmas, large and small, with which we grapple on a daily basis. Moving and memorable, Animal Person confirms in triumphant fashion Alexander MacLeod’s reputation as an author of bold, ingenious short fiction.

Klara Hveberg’s stunning debut novel reaches to the core of what it means to be human and vulnerable. Rakel is an only child, the prodigiously gifted daughter of a Norwegian father and Asian mother. She grows up in a small town, raised in an intellectually vibrant household immersed in art, music and literature. Not surprisingly, with her intellect setting her apart from her peers, she is often lonely and has difficulty making friends. As she matures, a passion for numbers and patterns emerges, which after high school motivates her to pursue a career in mathematics. She moves to Oslo to attend university, and there meets Professor Jakob Krogstad. The two develop a profound camaraderie, talking puzzles and problems. But it is at the primal level, when in Jakob’s presence, that Rakel is left aroused and breathless. In a short time—even though Jakob is more than 20 years her senior and a husband and father—Rakel and Jakob become lovers. In conversation, Jakob compares Rakel to the 19th-century Russian mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaya, a young genius who also had an affair with an older male mentor, and reveals he is planning to write a novel about Sofia’s life. Sofia becomes an object of Rakel’s curiosity, a constant presence in her thoughts, and she muses over a period of Sofia’s life when she seemed to renounce mathematics. At about the novel’s mid-point, with Rakel’s studies advancing and her accomplishments mounting, she is stricken with a baffling illness that saps her strength and renders her unable to work. At the same time, she wants Jakob to commit to their relationship, which he has promised to do when his daughters are old enough to accept his choice and live their lives without him. But this is not to be, and when Jakob chooses his wife Lea over her, Rakel is devastated. In the end, Rakel, now in her thirties and suffering debilitating symptoms, retreats from university life, returns to the small town of her youth and surrenders herself to the care of her parents. Hveberg’s novel, arresting, engaging, thought-provoking, is a cerebral exercise. And yet it is also a deeply touching inquiry into the nature of love and the spiritual connections that can arise between human beings. Permeated by melancholy and a sense of loss, Rakel’s story ebbs and flows like a body of water. Rakel, swept along by the current, subject to physical forces beyond her control, lives a life of the mind but is continually at the mercy of her heart, which yearns for the very things it cannot have. Impeccably translated from the Norwegian by Alison McCullough, this is beautiful writing that takes the reader on a surprising and unforgettable journey. Gripping and poignant, Lean Your Loneliness Slowly Against Mine engages the mind and the spirit like a great piece of music: harmonious, eloquent, haunting.

Alice Munro’s first collection of short stories is not simply a landmark work of Canadian fiction—it is a significant contribution to fiction written in English. These early stories are steeped in a glow of nostalgia and often turn their focus to young people yearning for independence and chafing against the role that society has assigned them. Also featured prominently are strained or lost emotional connections and diverging generational attitudes toward life and love. The settings are rural and small-town southwestern Ontario in the early to middle decades of the 20th century, a time of evolving lifestyles and hardscrabble self-sufficiency. A number of stories are narrated by children and depict their wonder and apprehension as they come face to face with a confusing but enthralling adult world. In “Walker Brothers Cowboy,” the young narrator and her younger brother go for a drive into the country with their father, a traveling salesman. Eventually they end up at a house where they meet a woman, Nora, whom, the narrator gradually realizes, is her father’s old sweetheart, and the shock of this hidden dimension of her father’s past thus revealed unveils to her the world as a place of depth and nuance that “darkens and turns strange” the moment you turn your back on it. Other stories place young women in awkward or oppressive social situations resulting from clashing attitudes toward gender roles. In “The Shining Houses,” a young mother, Mary, lives in a growing neighbourhood of newly constructed dwellings mingled in with the old. Mary admires her neighbour, Mrs. Fullerton, a resident of long standing, a cantankerous but strong-willed, independent woman who keeps chickens and sells eggs. Later, at a children’s birthday party that Mary attends with other young mothers like herself along with their young husbands, the conversation turns to a general disgust with Mrs. Fullerton’s “rundown” property and a plan to use a city ordinance to have her evicted. When Mary is asked to sign a petition she refuses, but her confusion is profound, and she leaves the party haunted by what she’s done to herself by resisting a notion that to her seems reprehensible but to others seems righteous and necessary. And in “The Office” a young mother, an aspiring fiction writer, bravely defies social and domestic norms by renting office space where she can work in peace, free of family distractions. But, to her chagrin, her concentration is disturbed, maddeningly and repeatedly, by her condescending and meddling landlord, who refuses to treat her and her artistic goals seriously. The stories are bracingly open-ended and, in their structural elasticity, imply endless vistas of narrative possibility. Throughout, Munro’s prose is precise and controlled and crowded with sensory detail. Her settings live and breathe: the natural world shimmers and pulsates; every texture, every sight, sound and smell of every interior space is rendered with stunning physicality that haunts the reader’s imagination like a lived memory. A virtuoso performance, The Dance of the Happy Shades received widespread acclaim when it was published in 1968 when the author was 37. A must-read for fans of the short story, this book also belongs on the reading list of every student of 20th-Century fiction.

Published in 1962, Janet Frame’s extraordinary third novel chronicles the adventures of three people living “on the edge of the alphabet”: a desolate outpost of the soul where feelings of worthlessness and crushing loneliness cannot be expressed. New Zealander Toby Withers, an epileptic, suffers as well from an acute form of social awkwardness that leaves him isolated and fretful. Zoe Bryce, a depressed middle-aged spinster from England, has left her position as a schoolteacher in humiliation after developing amorous feelings for a colleague that were not reciprocated. And boastful know-it-all Pat Keenan, an Irishman, lives an exceedingly prosaic life in London, where he drives a bus. The three cross paths on a passenger ship traveling from New Zealand to London. After the death of his supportive mother, and in defiance of his pragmatic father, Toby has decided to exert his independence, strike out on his own and see the world. He is also smarting after being rejected by a young woman whom he was convinced loved him because she tolerated his company and was on occasion nice to him. Zoe’s “working vacation” in NZ is over, and she is returning to England to face an uncertain future. And Pat is returning home as well after time off from his job. On board the ship, each traveling alone, Toby, Zoe and Pat form a loosely compatible trio, and in London their connection endures even as their quiet desperation intensifies. Pat returns to his squalid rooming house, where he has convinced Zoe that she should live as well, while Toby finds cramped, disagreeable quarters elsewhere. To support themselves, Zoe and Toby take menial, unfulfilling employment. For a time, Toby, Zoe and Pat are able to sustain themselves on their delusions. Toby, though largely unschooled and barely literate, has convinced himself that he will someday write a novel about “The Lost Tribe,” a notion, encouraged by his mother but dismissed as ridiculous by his father, that he guards closely and that has occupied him for years. Zoe, having been kissed on board the ship by a drunken sailor (the first kiss of her life), clings to the hope that love is not completely out of reach. And Pat makes his unexceptional life tolerable by puffing himself up with self-important claims, habitually exaggerating his accomplishments, offering unsolicited advice, and pushing people around, especially those, such as Zoe, who lack confidence and will be overwhelmed by his persistence. Eventually, however, each is compelled to give up on their dreams, with consequences that range from unfortunate to disastrous. The novel’s loose structure and Frame’s reliance on distorted interior monologue contribute a hazy, dreamlike quality to the action, which drifts from one event or encounter to the next. Throughout, Frame’s magical, often disorienting language leaps from the page: “But it is people, their shape, their presence, that are bulwark, bung-hole, asbestos wall. For the wind blows from fire, as well as from ice.” Impressionistic, sometimes bizarre, but bracingly original, The Edge of the Alphabet is also a compassionate and moving novel, one that confronts an age-old and tragic human enigma: that loneliness and its devastating effects can persist in a world filled with people searching for connection.

In Quiet Time, Grace is growing up in rural, coastal Newfoundland with two siblings and a pair of self-absorbed, artist parents. Grace’s father is a writer who warns the children not to bother him when he’s working, and for good measure has placed a creepy mask on his office door. Grace’s mother, a painter and sculptor, often goes missing, abandoning the family and staying absent for days or weeks at a time. Grace, preternaturally observant, is also a creative spirit who wants to be a writer, though she gets little encouragement at home and, after confiding in her English teacher and seeking his praise and approval, finds herself in a sexually abusive relationship. Katherine Alexandra Harvey’s debut novel chronicles Grace’s descent into addiction and mental distress, and her eventual recovery. At the age of seventeen, she meets Jack, a painter and friend of her mother. Jack also sells weed and consumes a variety of addictive substances, to which he introduces Grace. Grace, craving attention, falls in love with Jack, and over the course of their volatile, years-long relationship, becomes addicted to opiates and booze. Their lust- and drug-fueled partnership reaches its climax when Grace delivers a stillborn son. And it’s not long before Grace has attained new depths of despondency, resumes cutting herself and survives a suicide attempt. By this time Jack, whose painting career is flourishing, has left Grace for another woman. Harvey’s novel is unsparing and uncompromising and the story it tells is bleak. But Grace, alone with her grief and hitting bottom, somehow summons the strength to seek treatment and get herself admitted to hospital, pulling herself back from the brink just in time. Quiet Time, Harvey’s debut novel--difficult, disturbing, sometimes deeply unpleasant but always psychologically convincing--is also a strangely uplifting and triumphant work of gritty realism. With this novel, Katherine Alexandra Harvey announces herself as a fearless talent worth watching.

March 26, 2022

Best Reads of 2021

We have successfully passed through a strange and stressful year. But now we seem to be embarked on an even stranger one that promises even greater stress. Around the world, tensions are high. Covid is not done with us, not by a long shot. Supply lines are fractured. The price of everything is out of control.

Not much is certain. But one thing that is certain: books provide solace and distraction. So let’s keep reading!

My own reading in 2021 included the usual mix of titles new and old, prize winners and writers from the literary fringe, authors in translation, short story collections and novels ... an eclectic assortment, selected without plan, rhyme or reason. In other words, books that reflect my individual and admittedly peculiar tastes.

As always, I’m looking for interesting, memorable characters, fluency of expression, an original approach to storytelling. The books that affect us most deeply, that remain fondly and vividly in the memory, are ones that engage us on an intellectual and visceral level. The titles on this year’s list do that and more.

The task of choosing the best is never easy. Inevitably, worthy titles are left off the list. We can’t worry about that. If the left-offs are truly worthy—and we think they are—they’ll show up on somebody else’s list and receive the attention they deserve.

Jack Wang’s first collection of short fiction, We Two Alone, is a superior example of the form, beautifully crafted, emotionally resonant, and dramatically satisfying. Wang’s characters are primarily Chinese nationals and the sons and daughters of Chinese immigrants, people who are struggling to acclimatize to shifting geopolitical environments and/or deal with crises that threaten their way of life and sometimes their very survival. Racism is present in many of these stories, either hovering menacingly in the background or playing a dominant role in the lives of Wang’s characters. For instance, “The Valkyries” takes place in Vancouver and Banff shortly after the end of the First World War. Teenage orphan Nelson, who lives in Vancouver’s Chinatown and works in a laundry, loves hockey and is highly skilled, but being Chinese he’s denied the opportunity to play in an organized men’s league. Instead, when he discovers a women’s league, he assumes a disguise, passes himself off as “Nelly,” and becomes one of the stars for his team, the Valkyries. But when his deception is uncovered, the price he pays goes far beyond a mere settling of scores. A remarkable feature of Wang's fiction is his ability to convincingly evoke an assortment of cultural and historical contexts. In “The Nature of Things,” it is 1937. Young Chinese couple Frank and Alice must flee Shanghai because of the escalating hostilities with Japan. Frank, an American-educated physician, puts his pregnant wife on a train to safety but refuses to leave the city himself because of his work. From this point the story chronicles Alice’s desperate yearning and fears for her husband after the Japanese invasion, and her eventual realization that she will never see him again. The narrator of “The Night of Broken Glass” is recalling the time just prior to World War II when he, his father and stepmother lived in Vienna. The narrator’s father is a Chinese diplomat, versed in the ways of the world, wily and pragmatic, and the story tells of the father’s careful navigation of shifting political winds when the Nazis move into Austria and begin victimizing Jews, minorities and foreign nationals. “Everything in Between,” set in South Africa at the beginning of the Apartheid era, describes a Chinese family’s efforts to live a normal life under exceedingly challenging circumstances. “Bellsize Park” takes place in contemporary England and poignantly depicts the doomed relationship of two students: Peter, who is Chinese, and Fiona, who is English. And in “All Hallows” divorced Ernie’s irresponsible nature is thrown into sharp relief when he takes his children, Ben and Toby, trick-or-treating the day after Halloween because he’d failed to show up the night before as he’d promised. As good as these stories are, the outstanding piece in this collection is the masterful novella from which the volume takes its title. Leonard and Emily, both actors, are divorced. Leonard, in his late forties and still hunting for the Big Break, is entering a premature cognitive decline, which he recognizes because it is the same disorder that left his mother debilitated before her death. As he struggles with worsening symptoms, he recalls his years married to Emily, who finally gave up on the dream, retired from acting and left Leonard when he refused to do the same. Wang chronicles their life together from beginning to end: the shared aspirations, thwarted idealism, the minor triumphs countered by heartrending setbacks that marked their marriage and their careers. In the end, a crisis brings Leonard and Emily together one more time to enact a final scene before Leonard slips into the darkness and is unable to remember what they meant to each other. There is an effortless and seamless quality to Jack Wang’s writing that is particularly impressive. The nuts and bolts of craft, the scaffolding of plot, never intrude on the reader’s experience. In each of these tales Wang generates considerable narrative momentum by introducing his characters in place, slowly revealing their hopes and fears as he ramps up the stakes and the tension, and then letting the drama unfold in a manner that is patient and never forced. There is nothing cheap or maudlin going on here. Wang frequently elicits an emotional response from the reader, but without exception this reaction arises naturally out of the drama we’re witnessing. We Two Alone is a thoroughly engaging volume of short fiction by an exceptionally talented author. These are near flawless tales of personal struggle and modern angst: deeply empathetic, humane stories by a writer whose command of form and technique is unfailing.

Douglas Stuart’s gut-wrenching, prize-winning first novel tells the story of young Hugh “Shuggie” Bain, whose disastrous family life provides the framework for a sordid, tragic tale of alcoholism and abuse. We first encounter teenage Shuggie in 1992. He is fending for himself, working for cash in a Glasgow supermarket. But how did he get there? The middle sections of the book answer that question by taking us back to the early 1980s. Shuggie is the youngest of the three children of Agnes Bain, a beautiful, proud woman in her thirties who habitually takes up with selfish, manipulative, abusive men. His father Hugh, known as “Big Shug,” drives a taxi and routinely carries on with women of every stripe and description. For solace, for fun, and to blot out the world, Agnes drinks, invariably to excess. It’s a hardscrabble life that lacks hope and promise, but things go from bad to worse after Shug moves his family out of the cramped council flat they’ve been sharing with Agnes’s parents to a house in a remote mining village. This is post-industrial Scotland. The mine has all but shut down and almost everyone is on the dole. The mining town is a ruined, scorched place where, as Stuart tells us, “the land had been turned inside out,” a place neglected by those in power and despised by the people who live there, a place that breeds cruelty, misery and addiction. When Agnes’s drinking and resentment over his philandering become more trouble than they’re worth, Big Shug abandons his family altogether. Left alone with three children, Agnes’s dependence on alcohol escalates: most days she is dysfunctional by noon and comatose by evening. Money is tight and most of it goes on lager and vodka. Under these wretched circumstances the children—Shuggie, Catherine and Alexander (known as “Leek”)—care for themselves as best they can, pinning threadbare hopes on their mother’s rare and sporadic periods of sobriety while steeling themselves for the inevitable relapse. Despite her dereliction, Shuggie grows up idolizing his mother, in thrall to her beauty, serving her needs before his own, unaware that she’s deliberately raised him to be her enabler. His siblings are more mature and pragmatic, Catherine especially. She is the first to leave, absconding for a new life in South Africa. Later, in a drunken rage, Agnes throws Leek out of the house. Left alone with his mother, Shuggie struggles to assume necessary responsibilities and keep the household afloat while continuing to attend school and learning how to navigate an alien and hostile adult world. With Agnes having relinquished the roles of guardian and provider, Shuggie often goes hungry, but rarely does his mother go without drink. Still, Shuggie clings to hope, managing her moods, battling her cravings and encouraging sobriety. But it’s a battle against a relentless adversary that he has no chance of winning. Shuggie’s torment is magnified by growing up a misfit, aware that he is different from other boys but helpless to do anything about it, subject to taunting and physical abuse because of his proper speech, effeminate mannerisms and indifference to typical masculine pursuits, like football, girls and automobiles. The novel is long and structured in the manner of a symphony, with themes and motifs repeating and intensifying as the story progresses, the whole thing building to a devastating crescendo. Douglas Stuart’s down and dirty novel is not for the faint of heart. A portrait of anguished love and addiction, Shuggie Bain offers only faint flickering glimmers of hope. But it gets to the heart of the matter as it portrays the human will to survive, as only the best fiction can.

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s Booker Prize-nominated novel, His Bloody Project, purports to reconstruct, using contemporaneous documents, the story of a brutal triple slaying that took place in the Scottish village of Culduie. On an otherwise unexceptional day in August 1869, seventeen-year-old Roderick Macrae strolled up the lane from his house to the house of a neighbour, Lachlan Mackenzie. On the way there he was seen by another neighbour and spoke with her. She later testified that Roddy’s manner was normal: he was calm, gave her no cause for fear and did not raise her suspicions. Once at the Mackenzie house he used farming implements he had brought with him to bludgeon to death Lachlan’s daughter Flora and son Donnie, then waited for Lachlan. When Lachlan arrived home, Roddy beat him to death as well. Burnet’s novel consists of an account of the incident written by Roddy after his arrest, several witness statements, medical reports, an excerpt from a study of criminal psychology, and the trial transcript. Posing as an historical document, Burnet’s novel is thoroughly convincing, not to mention suspenseful and addictively readable. His detailed but never heavy handed prose brilliantly reconstructs the period in which the story is set, capturing the doleful spirit of the times, the superstitions that people held, the laws under which they laboured, the technologies they used, their pastimes and the beliefs that swayed attitudes and behaviours. The book, and Roddy himself, are infused with a mood of tragic inevitability. At the trial, Roddy’s motives come under close scrutiny. Experts and witnesses weight in on possible reasons for his actions. But questions persist. How can anyone know the content of another man’s mind? Graeme Macrae Burnet has written an astonishing and gripping novel that gives the reader plenty to think about.